Abstract

Background:

Hospitals and providers may increase hand surgery charges to compensate for decreasing reimbursement. Higher charges, combined with increasing utilization of ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs), may threaten the accessibility of affordable hand surgery care for uninsured and underinsured patients.

Methods:

We queried the Physician/Supplier Procedure Summary to collect the number of procedures, charges, and reimbursements of hand procedures from 2010 to 2019. We adjusted procedural volume by Medicare enrollment and monetary values to the 2019 US dollar. We calculated weighted means of charges and reimbursement that were then used to calculate reimbursement-to-charge ratios (RCRs). We calculated overall change and r2 from 2010 to 2019 for all procedures and stratified by procedural type, service setting, and state where service was rendered.

Results:

Weighted mean charges, reimbursement, and RCRs changed by + 21.0% (from $1,227 to $1,485; r2 = 0.93), +10.8% (from $321 to $356; r2 = 0.69), and -8.4% (from 0.26 to 0.24; r2 = 0.76), respectively. The Medicare enrollment-adjusted number of procedures performed in ASCs increased by 63.8% (r2 = 0.95). Trends in utilization and billing varied widely across different procedural types, service settings, and states.

Conclusions:

Charges for hand surgery procedures steadily increased, possibly reflecting an attempt to make up for reimbursements perceived to be inadequate. This trend places uninsured and underinsured patients at greater risk for financial catastrophe, as they are often responsible for full or partial charges. In addition, procedures shifted from inpatient to ASC setting. This may further limit access to affordable hand care for uninsured and underinsured patients.

Keywords: hand, anatomy, health policy, research & health outcomes, surgery, specialty, evaluation

Introduction

Uninsured and underinsured patients face substantial barriers in accessing affordable care. In 2018, 87 million Americans aged 19 to 64 were estimated to be inadequately insured and, as a result, to have received delayed care. 1 While the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) mandates provision of emergency medical care, 2 there is no comparable policy for elective care, whether for treatment of a chronic condition or the result of an acute injury. A notable majority of hand surgery procedures are performed electively or semi-electively. Therefore, uninsured and underinsured hand patients may face more substantial barriers in accessing care. This is supported by studies reporting that uninsured or underinsured patients are more likely to be transferred to other hospitals 3 or to have poorer outcomes after hand surgery. 4 Understanding utilization and billing of hand surgery procedures is critical to ensuring access for our uninsured and underinsured populations.

Medicare claims data provide a comprehensive overview of utilization, charges, and reimbursement rates for procedures billed to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) each year. 5 Medicare data also reflect broader trends in health care in the United States, as CMS payment structures tend to serve as the starting point for all other payer negotiations. 6 In recent years, providers have expressed concerns surrounding Medicare budget cuts for surgical services and declining reimbursement. 7 Hospitals or providers may increase charges to enhance revenue from private payers to make up for declining Medicare reimbursements. 8 CMS determines the amount of allowable payment for a given service, and any excess charges are not reimbursed. Medicare beneficiaries, who are responsible for a portion of Medicare-approved reimbursements, are not negatively affected by this potential “cost-shifting.” 9 However, cost-shifting negatively impacts uninsured and underinsured (ie, privately insured out-of-network) patients who are responsible for the full or a portion of charges that are the starting point of price negotiations across all payers. 6 Charges reported in Medicare data are the same for all insurance types. 6 Medicare data have been used to assess excessive hospital markups (eg. overall hospital charges in relation to Medicare allowable amounts) and their implications on the uninsured and underinsured populations.10,11

There has also been increasing utilization of ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) in providing surgical care 12 as a less costly alternative to hospitals for outpatient procedures. 13 Because uninsured/underinsured patients and those of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to receive care at ASCs, 14 this shift may limit access to surgical care. Additionally, numerous payers are beginning to limit performing lower acuity procedures in inpatient or hospital-based surgical centers, especially in lower tier coverage plans. 15 Despite these changes in healthcare financing and utilization, there is limited literature that provides a comprehensive analysis of trends of utilization, service setting, charges, and reimbursement for hand surgery procedures billed to Medicare. Because CMS data are frequently used as benchmarks for private insurers,16,17 we aimed to analyze the hand surgery procedures billed to Medicare Part B from 2010 to 2019 to better understand trends in billing practices and how this may impact disadvantaged patients.

Materials and Methods

We collected a comprehensive list of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for hand surgery from the American Board of Orthopedic Surgery. 18 We excluded procedures of the integumentary system from the CPT code list as these procedures can be nonspecific to hand surgery. We queried the Physician/Supplier Procedure Summary (PSPS), a nationwide database of procedures billed to Medicare Part B made available by CMS, with this CPT code list. Medicare Part B helps beneficiaries pay for outpatient and medical services from healthcare providers. 19 We included approved claims billed by hand surgeons (provider specialty code 40), plastic and reconstructive surgeons (provider specialty code 24), and orthopedic surgeons (provider specialty code 20) 20 from 2010 to 2019. We excluded any procedures that were not billed in every year of the study period. We collected the number of approved services, charges, reimbursements by CMS, service setting, and Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) for procedures performed during the study period. MACs represent geographic jurisdictions of private payers that process regional or statewide Medicare A or B claims, 21 and allowed us to identify the state in which the procedure was performed.

We adjusted utilization by Medicare enrollment to account for the increasing number of Medicare beneficiaries. 22 We calculated total change of enrollment-adjusted utilization of these procedures from 2010 to 2019. We also performed correlation analysis by calculating r, the Pearson correlation coefficient, to assess potential linear trends over time. We report r2, the coefficient of determination, as a measure of the strength of this correlation. r2 also serves as a goodness-of-fit test for a linear trend of changes in the monetary variables over time. An r2 value of 1 indicates a perfectly linear association between the variable and time, while a value of 0 indicates no linear association between the variable and time. We stratified procedures by the setting in which they were performed: ASC (place of service code 24), inpatient hospital (place of service code 21), outpatient hospital (places of service codes 19 and 22), and other. 23 Using the American Medical Association’s 24 categorization of CPT codes, we also categorized our list of CPT codes by procedure type. Medicare enrollment-adjusted utilization of the included procedures was assessed by procedure setting and by procedure type.

We adjusted all monetary values to 2019 US dollars. 25 We collected the Consumer Price Index from January 2010 to December 2019 from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics as a reference for the inflation rate. 25 To account for a wide range of charges, reimbursements, and utilization across different procedures, we calculated the weighted average of charges and reimbursements using the equation:

For a given CPT code, Weighted Averageyear is the weighted mean of charges or reimbursements for a given calendar year where Counti and Expensei are the number of services and charges or reimbursements, respectively. Weighted mean values of reimbursement and charge were calculated separately. We calculated the ratio between weighted mean reimbursement and weighted mean charge as the reimbursement-to-charge ratio (RCR), representing the proportion of payment received relative to the charged amount. A decreasing RCR would suggest either decreasing payment that negatively impacts providers or increasing charges that negatively impacts patients. As we did for utilization, we calculated total changes and r2 from 2010 to 2019 for charges, reimbursements, and RCRs for all procedures. We then stratified by procedural type and procedural setting to better understand the broader trends we observed.

Finally, to assess billing trends at a regional level, we stratified procedures by the state that processed the claims. We calculated state-level changes and r2 in weighted mean charges, weighted mean reimbursements, and RCRs over time. We performed all statistical analyses with R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). We created visual representations of the inter-state variation using Tableau Software (Salesforce, Mountain View, California). As these de-identified data are made publicly available by CMS and reported in aggregate, our institutional review board deemed this study exempt from review.

Results

After excluding 173 integumentary system CPT codes and 469 CPT codes that were not billed every year, we arrived at a list of 108 unique codes (Supplemental Material S1). From 2010 to 2019, 4 014 677 hand surgery procedures were billed with these hand surgery CPT codes to Medicare Part B (Supplemental Figure S1). Applications of casts and strapping and procedures to treat fractures and dislocation of the forearm and wrist were the most common types of procedures, accounting for 22.6% (N = 906,536) and 13.4% (N = 539,600) of all billed procedures, respectively (Table 1). From 2010 to 2019, the overall enrollment-adjusted utilization decreased from 7429 procedures to 6697 procedures (-9.9%, r2 0.74) per million Medicare beneficiaries. Utilization of casts and strapping and procedures for fractures and dislocations of the forearm and wrist both had over 30% decreases (Table 1). Although overall less frequently billed than some other procedure types, utilization of repair/revision/reconstruction for the hand and fingers and endoscopic, and arthroscopic procedures of the musculoskeletal system had the greatest increases over the 9 years.

Table 1.

Utilization of Hand Surgery Procedures in Medicare Part B From 2010 to 2019.

| Procedure type | Code range | No. of CPT codes | Total no. of procedures 2010-2019 | 2010 a | 2013 a | 2016 a | 2019 a | Total change | r 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 20103-69990 | 108 | 4,014,677 | 7429 | 7759 | 7156 | 6697 | –732 (–9.9%) | 0.74 |

| General introduction/removal—musculoskeletal | 20670-20694 | 5 (4.6%) | 289,472 (7.2%) | 567 | 576 | 501 | 424 | –143 (–25.2%) | 0.83 |

| Other forearm/wrist | 25000-25246 | 9 (8.3%) | 66,951 (1.7%) | 108 | 120 | 115 | 120 | + 12 (+11.2%) | 0.11 |

| Repair/revision/reconstruction—forearm/wrist | 25260-25447 | 8 (7.4%) | 146,048 (3.6%) | 184 | 249 | 278 | 309 | + 125 (+68.3%) | 0.89 |

| Fracture/dislocation—forearm/wrist | 25500-25670 | 13 (12.0%) | 539,600 (13.4%) | 1,159 | 1,075 | 927 | 781 | –378 (–32.6%) | 0.94 |

| Incision—hand/fingers | 26040-26055 | 3 (2.8%) | 418,320 (10.4%) | 571 | 758 | 794 | 866 | + 295 (+51.6%) | 0.79 |

| Repair/revision/reconstruction—hand/fingers | 26340-26535 | 8 (7.4%) | 40,325 (1.0%) | 38 | 70 | 72 | 103 | + 65 (+174.8%) | 0.91 |

| Application of casts and strapping | 29065-29280 | 11 (10.2%) | 906,536 (22.6%) | 1997 | 1776 | 1585 | 1274 | –723 (–36.2%) | 0.97 |

| Endoscopy/arthroscopy—musculoskeletal | 29848-29848 | 1 (0.9%) | 200,513 (5.0%) | 256 | 346 | 386 | 438 | + 182 (+71.3%) | 0.92 |

| Other musculoskeletal | 20103-26951 | 35 (32.4%) | 338,620 (8.4%) | 675 | 665 | 599 | 514 | –161 (–23.9%) | 0.84 |

| Other systems | — b | 15 (13.9%) | 1,068,292 (26.6%) | 1876 | 2125 | 1899 | 1869 | –7 (–0.4%) | 0.35 |

Note. CPT = Current Procedural Terminology.

Annual utilization is reported as procedures per million Medicare beneficiaries.

Dashes indicate that this procedural category includes CPT codes that are not within a defined range.

Procedures performed in ASCs, the inpatient setting, and the hospital-based outpatient setting accounted for 25.1%, 5.2%, and 33.4% of all procedures, respectively (Table 2). From 2010 to 2019, the utilization of ASCs increased by 63.8% (+857 procedures per million beneficiaries, r2 = 0.95), while the utilization of inpatient and outpatient settings decreased by 39.0% (-181 procedures per million beneficiaries, r2 = 0.89) and by 6.8% (-162 procedures per million beneficiaries, r2 = 0.55), respectively (Figure 1). This led to nearly identical levels of utilization of ASCs and outpatient settings (2202 vs. 2209 procedures per million beneficiaries, respectively) for hand surgery procedures in 2019.

Table 2.

Utilization of Different Service Settings for Hand Surgery Procedures in Medicare Part B From 2010 to 2019.

| Service setting | No. of CPT codes | Total no. of procedures 2010-2019 | 2010 a | 2013 a | 2016 a | 2019 a | Total change | r 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 108 | 4,014,677 | 7429 | 7759 | 7156 | 6,697 | –732 (–9.9%) | 0.74 |

| Ambulatory Surgical Center | 74 (68.5%) | 1,007,928 (25.1%) | 1345 | 1738 | 1948 | 2,202 | + 857 (+63.8%) | 0.95 |

| Inpatient Hospital | 63 (58.3%) | 210,472 (5.2%) | 465 | 432 | 345 | 283 | –182 (–39.0%) | 0.89 |

| Outpatient Hospital | 94 (87.0%) | 1,341,340 (33.4%) | 2371 | 2631 | 2384 | 2209 | –162 (–6.8%) | 0.55 |

| Others | 63 (58.3%) | 1,454,937 (36.2%) | 3249 | 2957 | 2479 | 2003 | –1246 (–38.3%) | 0.98 |

Note. CPT = Current Procedural Terminology.

Annual utilization is reported as procedures per million Medicare beneficiaries.

Figure 1.

Trends in utilization of different service settings of hand surgery procedures in Medicare from 2010 to 2019.

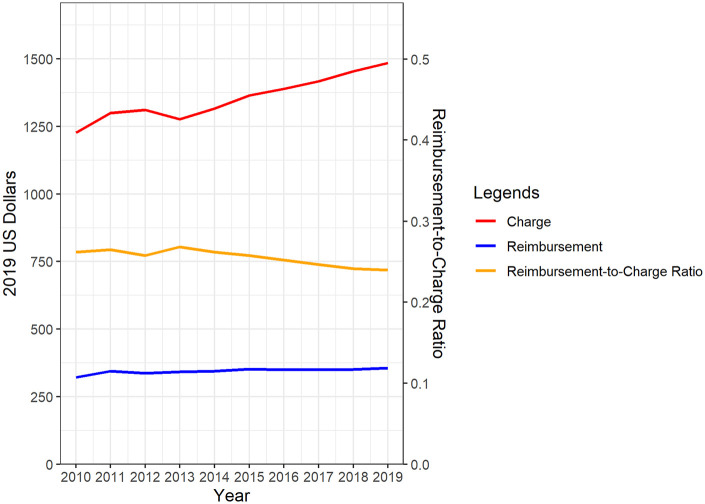

From 2010 to 2019, the overall charges, reimbursement, and RCRs changed by +21.0% (+$258 per procedure, r2 = 0.93), +10.8% (+$35 per procedure, r2 = 0.69), and -8.4% (-0.02, r2 = 0.76), respectively (Table 3, Figure 2). These trends varied widely across different types of procedures. Charges for endoscopy and arthroscopy of the musculoskeletal system decreased by 34.7% (-$1,046 per procedure, r2 = 0.66) over time, while charges for procedures to treat forearm and wrist fractures and dislocations increased by 44.3% (+$586 per procedure, r2 = 0.99). RCRs for general introduction/removal procedures decreased the most by 23.3% (-0.06, r2 = 0.97) and those for endoscopy and arthroscopy increased the most at + 52.7% (+0.08, r2 = 0.59).

Table 3.

Charges, Reimbursement, and RCRs of Hand Surgery Procedures in Medicare Part B From 2010 to 2019.

| Procedure type | Value type | 2010 a | 2013 a | 2016 a | 2019 a | Total change | r 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Charge | 1227 | 1277 | 1390 | 1485 | +258 (+21.0%) | 0.93 |

| Reimbursement | 321 | 342 | 350 | 356 | +35 (+10.8%) | 0.69 | |

| RCR | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.24 | –0.02 (–8.4%) | 0.76 | |

| General introduction/removal—musculoskeletal | Charge | 1323 | 1479 | 1638 | 1701 | +378 (+28.6%) | 0.97 |

| Reimbursement | 342 | 344 | 351 | 337 | –5 (–1.4%) | 0.10 | |

| RCR | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.20 | –0.06 (–23.3%) | 0.97 | |

| Other forearm/wrist | Charge | 3049 | 1738 | 1754 | 1812 | –1237 (–40.6%) | 0.49 |

| Reimbursement | 502 | 424 | 416 | 396 | –106 (–21.2%) | 0.74 | |

| RCR | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.22 | +0.05 (+32.6%) | 0.36 | |

| Repair/revision/reconstruction—forearm/wrist | Charge | 2588 | 2601 | 2688 | 2693 | +105 (+4.0%) | 0.41 |

| Reimbursement | 664 | 688 | 700 | 700 | +36 (+5.3%) | 0.17 | |

| RCR | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.00 (+1.2%) | 0.03 | |

| Fracture/dislocation—forearm/wrist | Charge | 1324 | 1483 | 1732 | 1910 | +586 (+44.3%) | 0.99 |

| Reimbursement | 483 | 531 | 554 | 577 | +94 (+19.4%) | 0.90 | |

| RCR | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.30 | –0.06 (–17.2%) | 0.96 | |

| Incision—hand/fingers | Charge | 1418 | 1415 | 1489 | 1507 | +89 (+6.3%) | 0.82 |

| Reimbursement | 273 | 279 | 278 | 278 | +5 (+1.7%) | 0.14 | |

| RCR | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.18 | –0.01 (–4.4%) | 0.77 | |

| Repair/revision/reconstruction—hand/fingers | Charge | 2373 | 2008 | 2261 | 2343 | –30 (–1.3%) | 0.32 |

| Reimbursement | 374 | 384 | 385 | 380 | +6 (+1.6%) | 0.04 | |

| RCR | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.00 (+2.9%) | 0.29 | |

| Application of casts and strapping | Charge | 207 | 216 | 233 | 236 | +29 (+13.9%) | 0.95 |

| Reimbursement | 81 | 84 | 80 | 76 | –5 (–7.1%) | 0.74 | |

| RCR | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.32 | –0.07 (–18.4%) | 0.95 | |

| Endoscopy/arthroscopy—musculoskeletal | Charge | 3018 | 2091 | 1921 | 1972 | –1046 (–34.7%) | 0.66 |

| Reimbursement | 484 | 506 | 500 | 483 | –1 (–0.2%) | 0.07 | |

| RCR | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.25 | +0.08 (+52.7%) | 0.59 | |

| Other musculoskeletal | Charge | 1190 | 1247 | 1389 | 1520 | +330 (+27.7%) | 0.97 |

| Reimbursement | 336 | 358 | 359 | 369 | +33 (+9.8%) | 0.60 | |

| RCR | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.24 | –0.04 (–14.1%) | 0.90 | |

| Other systems | Charge | 1675 | 1627 | 1727 | 1709 | +34 (+2.0%) | 0.26 |

| Reimbursement | 412 | 408 | 416 | 401 | –11 (–2.8%) | 0.39 | |

| RCR | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.23 | –0.01 (–4.7%) | 0.80 |

Note. RCR = reimbursement-to-charge ratio.

All monetary values were adjusted to the 2019 US dollars.

Figure 2.

Trends in charge, reimbursement, and reimbursement-to-charge ratio of hand surgery procedures in Medicare from 2010 to 2019.

When stratified by service setting, changes in charges, reimbursements, and RCRs for procedures performed in ASCs were minimal at + 4.6% (+$85 per procedure, r2 = 0.59), + 1.3% (+$5 per procedure, r2 = 0.04), and -3.1% (-0.01, r2 = 0.38), respectively (Table 4). In contrast, charges in the inpatient setting increased by 25.9% (+$415 per procedure, r2 = 0.98) with slight increase in reimbursement by 2.4% (+$9 per procedure, r2 = 0.05), resulting in 18.7% decrease (-0.04, r2 = 0.96) in RCR.

Table 4.

Charges, Reimbursements, and RCRs of Hand Surgery Procedures in Different Service Settings in Medicare Part B From 2010 to 2019.

| Service setting | Value type | 2010 a | 2013 a | 2016 a | 2019 a | Total change | r 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulatory surgical center | Charge | 1845 | 1812 | 1881 | 1930 | +85 (+4.6%) | 0.59 |

| Reimbursement | 425 | 439 | 439 | 430 | +5 (+1.3%) | 0.04 | |

| RCR | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.22 | –0.01 (–3.1%) | 0.38 | |

| Inpatient hospital | Charge | 1602 | 1706 | 1910 | 2017 | +415 (+25.9%) | 0.98 |

| Reimbursement | 379 | 388 | 399 | 388 | +9 (+2.4%) | 0.05 | |

| RCR | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.19 | –0.04 (–18.7%) | 0.96 | |

| Outpatient hospital | Charge | 1833 | 1724 | 1787 | 1808 | –25 (–1.4%) | 0.10 |

| Reimbursement | 441 | 444 | 446 | 441 | 0 (+0.1%) | 0.16 | |

| RCR | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.00 (+1.5%) | 0.01 | |

| Others | Charge | 476 | 503 | 548 | 565 | +89 (+18.7%) | 0.95 |

| Reimbursement | 182 | 189 | 181 | 175 | –7 (–4.4%) | 0.63 | |

| RCR | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.31 | –0.07 (–19.4%) | 0.95 |

Note. RCR = Reimbursement-to-Charge Ratio.

All monetary values were adjusted to the 2019 US dollars.

In our state-level analysis, changes in charges, reimbursements, and RCRs varied across states (Supplemental Tables S1-S3). The increase in weighted mean charges was consistent across the country, as every state except for 4 had an increase (Figure 3). Hand surgery procedures billed in Alaska underwent the greatest changes in charges per procedure from $1,610 to $4,991 (+210.0%, r2 = 0.95), while those in Nevada decreased by 29.7% from $2813 to $1978 (-$835, r2 = 0.32). The increase in weighted mean reimbursements was consistent across the country, with every state undergoing an increase; this ranged from an increase of 0.6% (+$2 per procedure, r2 = 0.04) in New York to an increase of 95.3% (+$310 per procedure, r2 = 0.86) in Alaska. Overall, RCR decreased in most states over the study period (Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Percent (%) change in charge of hand surgery procedures from 2010 to 2019 by state. Maps made with OpenStreetMap© using Tableau software.

Discussion

Our study of nationwide claims of hand surgery procedures billed to Medicare Part B suggests that during the study period utilization of ASCs increased by more than half while all other service settings saw a decrease in hand surgery volume. The overall charges for hand surgery procedures increased by more than 20%. Although Medicare reimbursement also increased, charges increased more resulting in overall decreasing reimbursement relative to charges. There were relatively small changes in reimbursement or charges for procedures performed in ASCs or outpatient settings, but charges from inpatient hospitals increased by more than 25% over time.

Some of these findings are consistent with previous studies, while others were not. Malik et al 26 reported decreasing reimbursement rates for hand surgery procedures over the same period; however, they only included 20 common procedures while our query included 108 hand surgery procedures. Given that reimbursement trends varied widely for procedural categories, this difference may be due to inclusion of different CPT codes for the 2 studies. These seemingly conflicting findings suggest it is unlikely that reimbursement for all hand surgery procedures have changed in the same direction, and likely some have increased while others have decreased. Additional research is needed to further elucidate the nuanced changes in reimbursement in surgery. Nonetheless, the steady increase in charges is consistently shown, and may reflect an attempt by providers and hospitals to offset reimbursements perceived to be inadequate from private payers. 6 Although this does not impact Medicare beneficiaries, 9 it puts already vulnerable uninsured and privately insured out-of-network patients at greater financial risk as they may be held responsible for the charged amounts. Increasing charges can also negatively impact privately insured in-network patients because negotiated rates may be based on charges, and coinsurance is often based on negotiated rates.27,28

We found increased utilization of ASCs for hand surgery procedures, consistent with other studies. 12 Since CMS adopted the prospective reimbursement model for inpatient services billed to Medicare in 1983, 29 hospitals were incentivized to provide surgical care in outpatient settings. 13 From 2001 to 2010, the usage of ASCs increased by more than half. 12 In 2003, in response to the rapidly growing utilization of ASCs, CMS adopted the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act in order to minimize changes in reimbursement rates for ASCs. 30 From 2008 to 2012, CMS limited maximum reimbursements to ASCs to a set proportion of reimbursements made to hospitals. 31 These legislative changes were reflected in our results, as reimbursement for hand surgery procedures performed in ASCs changed by only 1.3% over the study period.

While ASCs may serve as a safe and cost-effective alternative for certain procedures for relatively healthy patients, 13 the shift to ASCs is concerning for uninsured patients. For example, Strope et al 14 reported that patients of low socioeconomic status are less likely to receive orthopedic procedures at ASCs. This may be explained by the financial structure of ASCs. Most ASCs are for-profit organizations largely driven by physician ownership and external investors. 32 This poses a complex incentive structure in that physicians and ASCs are likely disincentivized from caring for patients with no or inadequate insurance. 14 Specialty hospitals have been reported to preferentially provide certain services for profitable patients, saturating the ability of general hospitals to cover these services for uninsured patients. 32 The concomitant increase in charges and ASC utilization is particularly concerning for patients aged 50 to 64 years, an age group that accounts for 20% of the U.S. population. 33 More than 10% of this population is uninsured (as compared to <1% for those 65+), 34 and almost one-third suffers from chronic illnesses and functional limitations. 35 The increase in already high charges—as high as 10 times the costs of procedures performed in hospitals 11 —and shift to ASCs limits access to affordable hand care for this age group with high uninsured rates and frequent medical needs.

Our findings on the shift to ASC-based hand surgery have implications on the underinsured patient population as well. Some payers have introduced site of service restrictions on surgical procedures, limiting low-acuity surgeries from being performed in inpatient or even hospital-based outpatient settings. 15 These regulations may partly explain our findings and recent shifts in other orthopedic procedures, including knee and hip arthroplasties, to outpatient settings.36,37 Underinsured patients are typically of lower socioeconomic status. 38 Because ASCs may perform insurance profiling of patients, 14 underinsured patients may be denied services at ASCs. Additionally, to optimize their insurance mix, ASCs are less likely to be established in low-income areas. 14 Therefore, even if underinsured patients are offered surgery, they may lack the resources to travel greater distances to receive care at ASCs. 39 With ASCs becoming the primary setting for hand surgery, underinsured patients may face increasing difficulty accessing hand care due to numerous barriers.

In our state-level analysis, although all states except 4 demonstrated trends similar to the national trend, there was wide variation in billing practices for hand surgery across different states. Such variations may be due to different state regulations on hospital charges. An example of state actions to regulate hospital charges is the implementation of all-payer claims databases (APCDs). APCDs are large state-level databases of healthcare claims from both public and private payers. 40 APCDs are designed to promote healthcare cost transparency and provide data for policymakers to make informed decisions. 40 Currently, only 18 states have operational APCDs, reflecting variabilities in state participation in regulating price transparency. 40 In addition, there may be hospital-level factors behind these differences, such as variation in the volume of different types of hand surgeries performed at individual hospitals. Further research is needed to evaluate the relative importance of state- and hospital-level factors on hospital charges for hand surgery.

There are several limitations to our study. First, we grouped procedures based on how the American Medical Association categorizes CPT codes. Because changes in reimbursement policy are not necessarily based on this categorization, our analysis by procedure type may have obscured trends for certain procedures. Second, we analyzed trends in charges and reimbursements at the state level. Although this elucidates trends that result from state policy, this approach does not incorporate other important regional factors that influence billing trends. Further research accounting for key geographic factors, including rurality, cost of living, wage index, and type of hospital is needed to better estimate potential regional differences in Medicare utilization and billing practices in the United States. Additionally, although hospital charges represent the starting point for negotiations and are consistent regardless of payer, 6 we could not assess the role that discounts may have played. 11 Uninsured and underinsured patients may also apply for Medicaid to receive benefits to cover their hand care. Therefore, challenges in estimating the magnitude of the financial impact of increasing charges on uninsured and underinsured patients remain. Further research with non-Medicare patient data is necessary to directly apply our observations to uninsured and underinsured patients. Finally, insurance contracts vary widely in their negotiation policies. Although CMS policies are the standard used by many private payers to negotiate payments, 6 this variation further obscures the impact of billing trends on access to care for uninsured and underinsured patients.

In conclusion, in our nationwide study of hand surgery procedures billed to Medicare Part B, we characterized trends in utilization, billing, and service setting over the past decade. Overall charges increased more than Medicare reimbursements, resulting in decreasing reimbursement relative to charges for hand surgeons. ASCs are quickly becoming the primary service setting for hand surgery procedures. These findings raise concerns regarding access to affordable hand surgery care for uninsured and underinsured patients. Rising charges place them at increased risk for catastrophic medical expenditure while increased utilization of ASCs limits their access.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-han-10.1177_15589447221077367 for Billing and Utilization Trends for Hand Surgery Indicate Worsening Barriers to Accessing Care by Jung Ho Gong, Chao Long, Adam E. M. Eltorai, Kavya K. Sanghavi and Aviram M. Giladi in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-han-10.1177_15589447221077367 for Billing and Utilization Trends for Hand Surgery Indicate Worsening Barriers to Accessing Care by Jung Ho Gong, Chao Long, Adam E. M. Eltorai, Kavya K. Sanghavi and Aviram M. Giladi in HAND

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available in the online version of the article.

Ethical Approval: The Institutional Review Board determined that this research is exempt from review.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: The research did not involve human subjects.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Jung Ho Gong  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0382-8279

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0382-8279

Aviram M. Giladi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7688-957X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7688-957X

References

- 1. Collins SR, Bhupal HK, Doty MM. Health insurance coverage eight years after the ACA: fewer uninsured Americans and shorter coverage gaps, but more underinsured. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/feb/health-insurance-coverage-eight-years-after-aca. Published 2019. Accessed January 24, 2021.

- 2. Katz MH, Wei EK. EMTALA—a noble policy that needs improvement. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(5):693-694. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thakur NA, Plante MJ, Kayiaros S, et al. Inappropriate transfer of patients with orthopaedic injuries to a level I trauma center: a prospective study. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(6):336-339. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181b18b89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brady CI, Saucedo JM. Providing hand surgery care to vulnerably uninsured patients. Hand Clin. 2020;36(2):245-253. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mahmoudi E, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. A review of the use of Medicare claims data in plastic surgery outcomes research. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3(10):e530. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bai G, Chanmugam A, Suslow VY, et al. Air ambulances with sky-high charges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1195-1200. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American College of Surgeons. American College of Surgeons strongly opposes proposed Medicare physician fee schedule. Date unknown. https://www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2020/cms-rule-080420. Accessed November 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frakt AB. How much do hospitals cost shift? A review of the evidence. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):90-130. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Medicare. Medicare costs at a glance. Date unknown. https://www.medicare.gov/your-medicare-costs/medicare-costs-at-a-glance. Accessed January 28, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bai G, Anderson GF. Variation in the ratio of physician charges to Medicare payments by specialty and region. JAMA. 2017;317(3):315-318. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bai G, Anderson GF. Extreme markup: the fifty US hospitals with the highest charge-to-cost ratios. Health Aff. 2015;34(6):922-928. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hollenbeck BK, Dunn RL, Suskind AM, et al. Ambulatory surgery centers and outpatient procedure use among Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2014;52(10):926-931. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Munnich EL, Parente ST. Procedures take less time at ambulatory surgery centers, keeping costs down and ability to meet demand up. Health Aff. 2014;33(5):764-769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Strope SA, Sarma A, Ye Z, et al. Disparities in the use of ambulatory surgical centers: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:121. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. United Healthcare. Outpatient surgical procedures: site of service. https://www.uhcprovider.com/content/dam/provider/docs/public/policies/attachments/comm-plan/outpatient-surg-procedures-site-service-multi-state-cs-06012020.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed January 24, 2021.

- 16. Rosenow JM, Orrico KO. Neurosurgeons’ responses to changing Medicare reimbursement. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37(5):E12. doi: 10.3171/2014.8.FOCUS14427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marks SD, Greenlick MR, Hurtado AV, et al. Ambulatory surgery in an HMO. A study of costs, quality of care and satisfaction. Med Care. 1980;18(2):127-146. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198002000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery. CPT codes. Date unknown. https://www.abos.org/subspecialties/surgery-of-the-hand/cpt-codes/. Accessed January 11, 2021.

- 19. Are you a hospital inpatient or outpatient? Date unknown. https://www.medicare.gov/sites/default/files/2018-09/11435-Are-You-an-Inpatient-or-Outpatient.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2021.

- 20. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. New physician specialty code for micrographic dermatologic surgery (MDS) and adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) and a new supplier specialty code for home infusion therapy services. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/MM11750.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed January 24, 2021.

- 21. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. What is a MAC. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Contracting/Medicare-Administrative-Contractors/What-is-a-MAC. Published 2020. Accessed January 25, 2021.

- 22. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS program statistics. Date unknown. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMSProgramStatistics. Accessed November 26, 2020.

- 23. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Place of service code set. Date unknown. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/place-of-service-codes/Place_of_Service_Code_Set. Accessed January 11, 2021.

- 24. American Medical Association. CPT® overview and code approval. Date unknown. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/cpt/cpt-overview-and-code-approval. Accessed December 31, 2020.

- 25. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index historical tables for U.S. city average: mid-Atlantic information office. Date unknown. https://www.bls.gov/regions/mid-atlantic/data/consumerpriceindexhistorical_us_table.htm. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- 26. Malik AT, Khan SN, Goyal KS. Declining trend in Medicare physician reimbursements for hand surgery from 2002 to 2018. J Hand Surg Am. 2020;45(11):1003-1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2020.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital price transparency frequently asked questions (FAQs). Date unknown. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/hospital-price-transparency-frequently-asked-questions.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2021.

- 28. Beyond the Basics. Key facts: cost-sharing charges. https://www.healthreformbeyondthebasics.org/cost-sharing-charges-in-marketplace-health-insurance-plans-answers-to-frequently-asked-questions/. Published 2020. Accessed March 13, 2021.

- 29. Leader S, Moon M. Medicare trends in ambulatory surgery. Health Aff. 1989;8(1):158-170. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.8.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hastert JD. H.R.1 - 108th Congress (2003-2004): Medicare prescription drug, improvement, and modernization act of 2003. https://www.congress.gov/bill/108th-congress/house-bill/1. Published 2003. Accessed January 11, 2021.

- 31. US Government Accountability Office. GAO report to congressional committees— MEDICARE: payment for ambulatory surgical centers should be based on the hospital outpatient payment system. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-07-86.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed January 11, 2021.

- 32. Shactman D. Specialty hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, and general hospitals: charting a wise public policy course. Health Aff. 2005;24(3):868-873. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. PEPAGESEX annual estimates of the resident population for selected age groups by sex for the United States, states, counties, and Puerto Rico commonwealth and Municipios. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/tables/2010-2018/state/asrh/. Published 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cha AE, Cohen RA. Reasons for being uninsured among adults aged 18-64 in the United States, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db382.htm. Published 2019. [PubMed]

- 35. Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Choi BY. Unmet healthcare needs and healthcare access gaps among uninsured U.S. adults aged 50-64. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2711. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shapira J, Chen SL, Rosinsky PJ, et al. Outcomes of outpatient total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. Hip Int. 2021;31(1):4-11. doi: 10.1177/1120700020911639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Edwards PK, Milles JL, Stambough JB, et al. Inpatient versus outpatient total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2019;32(8):730-735. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Link CL, McKinlay JB. Only half the problem is being addressed: underinsurance is as big a problem as uninsurance. Int J Health Serv. 2010;40(3):507-523. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.3.g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Calfee RP, Shah CM, Canham CD, et al. The influence of insurance status on access to and utilization of a tertiary hand surgery referral center. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):2177-2184. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. State actions related to transparency and disclosure of health and hospital charges. Date unknown. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/transparency-and-disclosure-health-costs.aspx

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-han-10.1177_15589447221077367 for Billing and Utilization Trends for Hand Surgery Indicate Worsening Barriers to Accessing Care by Jung Ho Gong, Chao Long, Adam E. M. Eltorai, Kavya K. Sanghavi and Aviram M. Giladi in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-han-10.1177_15589447221077367 for Billing and Utilization Trends for Hand Surgery Indicate Worsening Barriers to Accessing Care by Jung Ho Gong, Chao Long, Adam E. M. Eltorai, Kavya K. Sanghavi and Aviram M. Giladi in HAND