Abstract

Background.

Patient clinical collateral information is critical for providing psychiatric and psychotherapeutic care. With the shift to primarily virtual care triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, psychotherapists may have received less clinical information than they did when they were providing in-person care. This study assesses whether the shift to virtual care had an impact on therapists’ use of patients’ electronic and social media to augment clinical information that may inform psychotherapy.

Methods.

In 2018, we conducted a survey of a cohort of psychotherapists affiliated with McLean Hospital. We then re-approached the same cohort of providers for the current study, gathering survey responses from August 10, 2020 to September 1, 2020 for this analysis. We asked clinicians whether they viewed patients’ electronic and social media in the context of their psychotherapeutic relationship, what they viewed, how much they viewed it, and their attitudes about doing so.

Results.

Of the 99 respondents, 64 (64.6%) had viewed at least 1 patient’s social media and 8 (8.1%) had viewed a patient’s electronic media. Of those who reported viewing patients’ media, 70 (97.2 %) indicated they believed this information helped them provide more effective treatment. Compared to the 2018 pre-pandemic data, there were significantly more clinicians with greater than 10 years’ experience reporting media use in therapy. There was also a significant increase during the pandemic in the viewing of media in younger adults and a trend toward an increase in older adults.

Conclusions.

Review of patients’ electronic and social media in therapy became more common among clinicians at a large psychiatric teaching hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings support continuing research about how reviewing patients’ media can inform and improve clinical care.

Keywords: social media, digital health, psychotherapy, COVID-19, telemedicine, telehealth

A 2020 report indicated that people spend 40% of their waking life online, estimating that individuals occupy about 6 hours and 43 minutes a day online and 2 hours and 24 minutes a day specifically on social media.1 Online activity has only increased with the COVID-19 outbreak.2 A survey from The Pew Research Center found that 53% of adults in the U.S. indicated that “the internet has been essential for them personally during the pandemic” and an additional 34% reported it being “important, but not essential.”3

With so much of our lives online, activity on social media can be a source of collateral information that is crucial for the provision of effective psychiatric and psychotherapeutic care. Collateral information, whether from family members4 or from patients’ writings in expressive therapy,5 has been widely used to inform psychotherapy. Several recent studies found that clinicians can make use of electronic and social media data to analyze a patient’s response to psychotherapeutic treatment or to identify a potential psychiatric illness.6 Differences in language use between healthy individuals and those with a known psychiatric diagnosis have also been demonstrated.7,8 Another study found that examining the language used in emails by patients with social anxiety could predict therapeutic outcomes.9 In addition, clinicians using an interpersonal therapy framework analyzed text messages on different platforms to better understand their patient’s communication patterns and interpersonal dynamics.10

Researchers have also explored clinicians’ and patients’ attitudes toward using electronic and social media information in the context of clinical care. There is evidence to suggest that patients are generally willing to share these data with clinicians, and that clinicians frequently access online resources for information about patients.11–13

However, the question of how these practices may have changed during the widespread transition to virtual care during the COVID-19 pandemic has not been extensively studied. The pandemic increased the use of social media and virtual communication in general,2 potentially providing more relevant information about patients’ mental health. The aim of this study was to assess whether and how clinicians had altered their use of electronic and social media as a source of relevant collateral information to support psychotherapy. We conducted a follow-up to a survey that was conducted before the pandemic in 201814 to understand whether there had been changes in clinicians’ use of this content since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesized that, after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychotherapists would have increased their use of their patients’ social and electronic media in psychotherapy as a way of obtaining collateral information.

METHODS

Participants

The participants in this study were 99 outpatient clinicians providing psychotherapy services at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. We used an online survey instrument developed and utilized for the initial study in 2018 that assessed the use of social and electronic media in psychotherapy. We sent an email with a link to the survey to the 402 clinicians listed in the McLean Hospital outpatient clinician mailing list in 3 waves. beginning in August 2020. The emails reached 397 outpatient clinicians as 5 email addresses were no longer valid. Ninety-nine clinicians completed the survey, representing a 25% response rate. Participants reflected a variety of professional backgrounds and psychotherapeutic approaches provided at McLean Hospital. In the email, we informed the participants that the purpose of the survey was to assess clinicians’ use of patients’ electronic media in psychotherapy.

Survey

We used a 17-item survey that we had previously developed and implemented in 201814 to assess clinician attitudes and behaviors about using patients’ electronic media in psychotherapy. We did not add any additional questions from the 2018 survey or ask clinicians for demographic information. The survey was sent as a private Google Survey invitation link to a professional, secure email address. Once we completed data collection, the data were stored, downloaded, and saved on private Massachusetts General Brigham Healthcare servers.

Data Analysis

The data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS V 25 statistical software. We generated descriptive statistics for certain items. However, the main statistical approach was Pearson’s chi square test of independence, which was used to compare differences between responses to the current survey and those from the 2018 survey. This project met the criteria to be a quality improvement initiative (QII) at McLean Hospital and was determined not to need the direct supervision of the Institutional Review Board (IRB), as per its own criteria.

RESULTS

Respondent Demographics

Overall, 99 clinicians responded to the survey. Table 1 lists the training backgrounds of the responding clinicians. Thirty-one clinicians (31.3 %) had less than 10 years of clinical experience, 23 (23.2 %) had 10 to 20 years of experience, and 44 (44.4 %) had more than 20 years of experience. Information was missing for 1 respondent. We noted no significant differences between the 2018 survey and the 2020 survey in terms of the respondent clinicians’ degrees or years in practice.

Table 1.

Professional degrees held by the 99 clinician survey respondents.

| Degree Type | N (%) |

|---|---|

| MD | 29 (29.3) |

| PhD | 28 (28.3) |

| LICSW | 31 (31.3) |

| APRN | 7 (7.1) |

| MD/PhD | 1 (1.0) |

| LMHC | 1 (1.0) |

Abbreviations: MD, Doctor of Medicine; PhD, Doctor of Philosophy; LCSW, Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker; APRN, Advanced Practice Registered Nurse; LMHC, Licensed Mental Health Counselor.

Note: data were missing for 2 respondents

Overall Viewing Rates

Of the 99 respondents, 64 (64.6 %) indicated that they had viewed at least one patient’s social media, and 8 (8.1 %) reported that they had viewed a patient’s electronic media (eg, text messages or email). There were 6 clinicians who reported that they did not use electronic or social media in sessions but who did report the use of text messages in therapy. Furthermore, 6 clinicians denied using social or electronic media in sessions but reported the use of emails. These clinicians’ responses were not included in the analyses of the data. No significant differences were found between responses before and during the pandemic for any of these types of media. Responses showed a decrease in the use of blogs during the pandemic compared with before the pandemic, but the difference met criteria only for trend-level significance (P = 0.051).

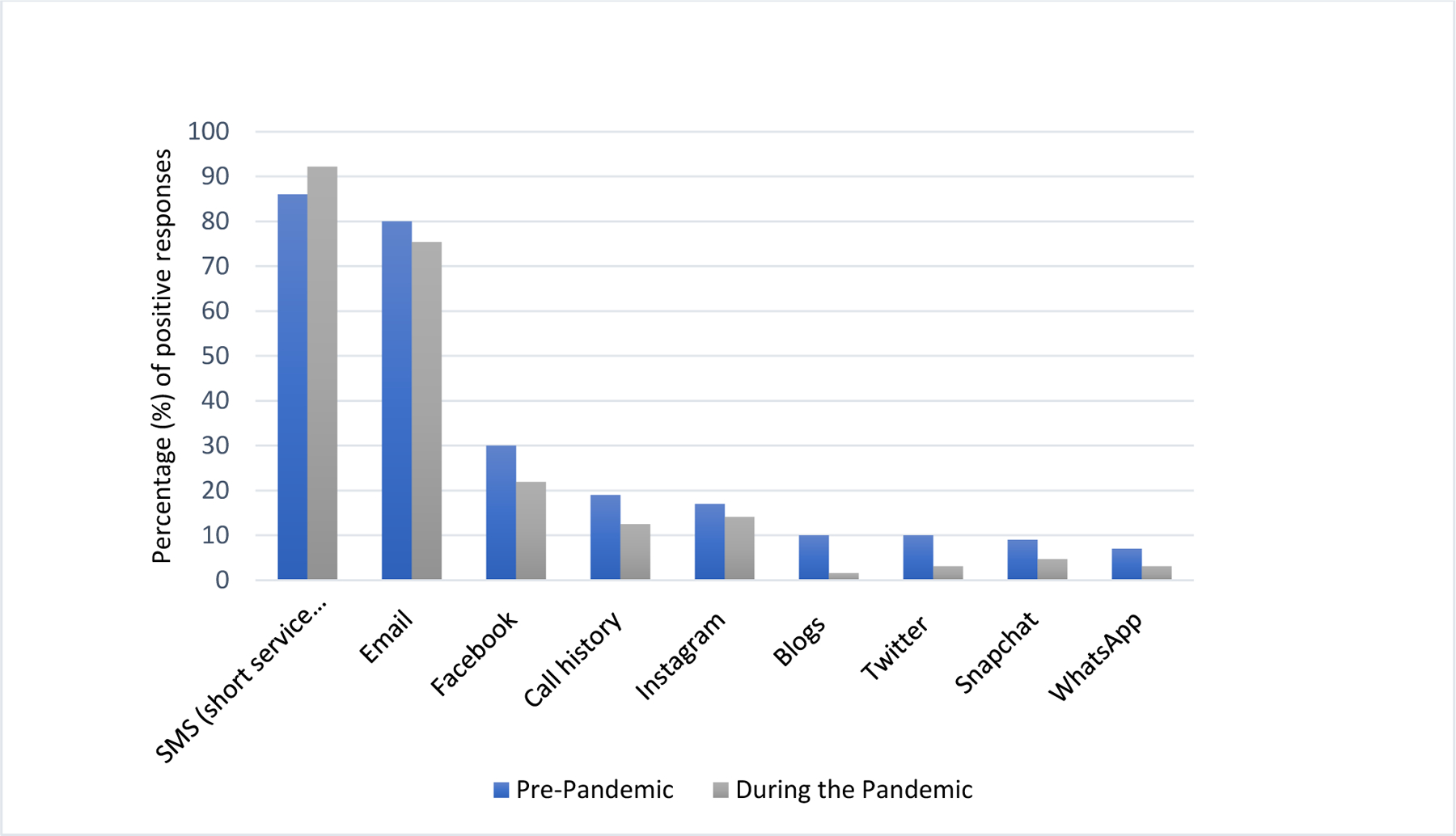

Types of Media Viewed

Figure 1 summarizes the breakdown of patients’ social and electronic media platforms that clinicians viewed. A total of 59 of 64 respondents to this question (92.2 %) viewed SMS text messages and 49 (76.6 %) viewed emails, making these the most frequently accessed platforms. The use of either SMS text messages or email was greater than the use of any other type of media. We found no significant differences in reported use of different types of media between the 2018 and the 2020 surveys.

Figure 1.

Types of media content viewed by clinicians both before and during the pandemic, as shown by percentage of positive (“yes”) responses.

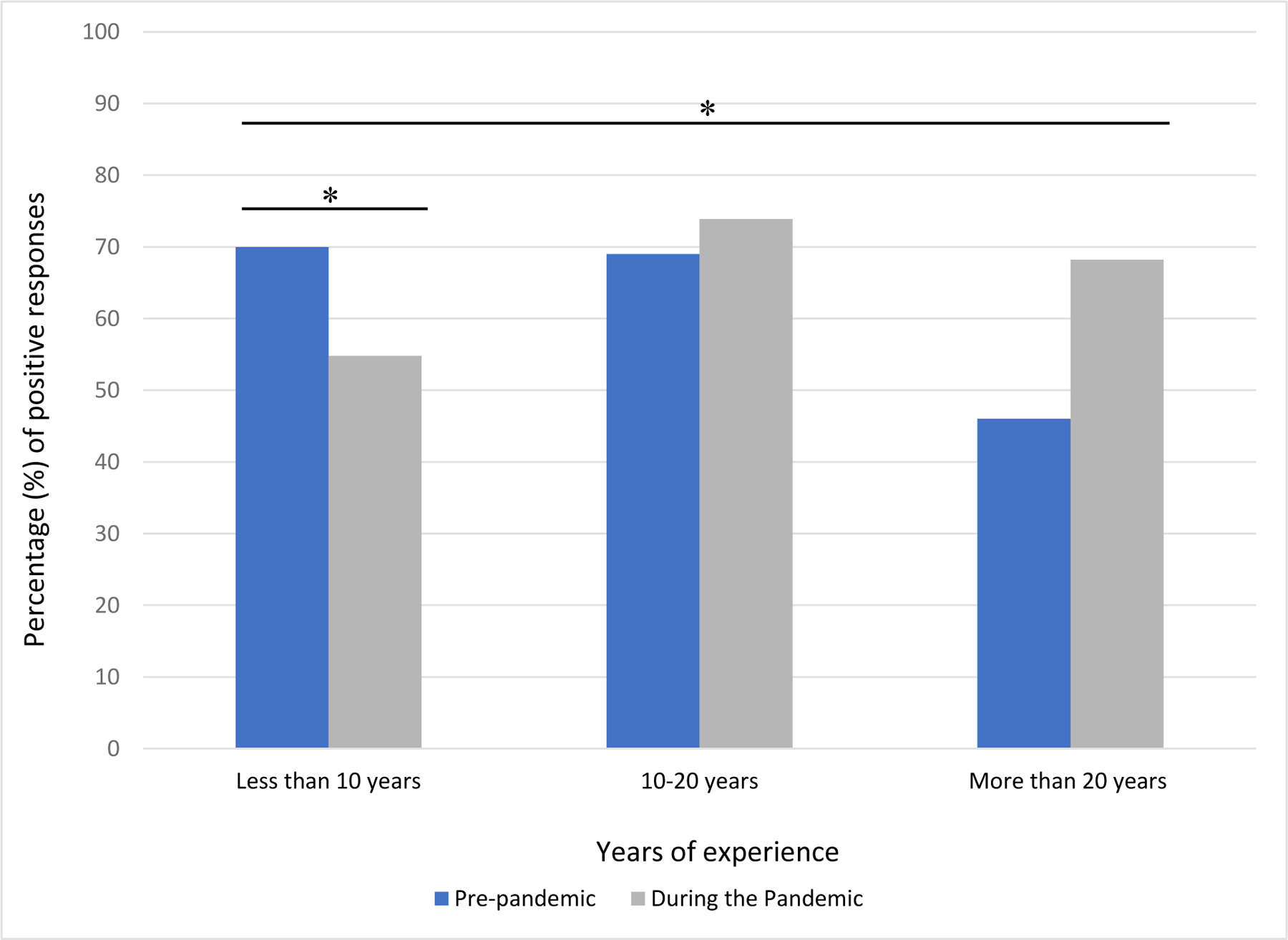

Clinical Experience and Media Use

Figure 2 summarizes how patterns of viewing media varied on the basis of clinicians’ experience. A total of 17 of the 31 respondents (54.8 %) with less than 10 years of experience and 17 of the 23 respondents (73.9 %) with 10 to 20 years of experience stated that they had viewed a patient’s social or electronic media. Meanwhile, 30 of the 44 respondents (68.2 %) with more than 20 years of experience also reported viewing electronic or social media. However, there was a significant difference between survey waves in terms of clinical experience and media use (χ 2 = 8.02, N = 135 P = 0.018). In the pre-pandemic wave, there were significantly more clinicians with less than 10 years of experience reporting the use of electronic and/or social media in therapy compared with their responses in the pandemic wave (χ 2 = 5.73, N = 135, P = 0.017), Conversely, the other 2 more experienced cohorts reported greater use of electronic/social media after the onset of the pandemic (though these differences did not achieve significance) . We also conducted similar analyses evaluating if this relationship varied by the clinician’s professional degree, but we did not find any significant differences or even non-statistically significant trend between groups.

Figure 2.

Comparison of clinician’s years of experience and use of electronic or social media content pre-pandemic and during the pandemic, as seen in percentage of positive (“yes”) responses.

* Indicates statistical significance in the comparison of groups. The comparisons that achieved this reflect a significant decrease among clinicians with fewer than 10 years of experience, but an overall significant increase across the entire sample.

Changes in Patterns of Viewing Electronic Media

We noted a significant increase in the viewing of media during the pandemic when clinicians were working with adult patients (χ 2 = 6.58, N = 99, P = 0.010) and a trend toward an increase in viewing media of older adult patients (χ 2 = 5.33, N = 99, P = 0.021); this result was not significant following a Bonferroni correction that set the P value at 0.013). We did not note an increase in viewing media of adolescents and young adults.

We asked whether clinicians had discussed privacy with patients and noted that 52 of 64 clinicians (81%) who had accessed patients’ social and electronic media indicated that they had discussed issues of privacy with the patients. There were no significant differences in these responses before and during the pandemic.

Most clinicians who discussed privacy initiated the conversations themselves. However, 13 of 64 clinicians (20%) reported that their patients raised privacy concerns regarding sharing this type of content, compared with only 3% of clinicians before the pandemic, which was a significant increase (χ 2 = 15.21, N = 135, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to examine whether the switch from in-person to telecare-based psychotherapy brought about by the pandemic led to changes in clinicians’ use of patients’ social and electronic media to inform psychotherapy. We hypothesized that clinicians would make more use of electronic media platforms for relevant information on mental health during the pandemic, as research suggests that people’s use of social media platforms during this time increased,2 and therefore made these platforms more central to daily life15.

Overall, we noted that there were many similarities in the use of electronic media in psychotherapy before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, but also some notable differences. We found that during the pandemic, clinicians with more years of experience were more likely to incorporate electronic media into therapy than they had previously in 2018 before the pandemic. In the study we conducted in 2018 (pre-pandemic), we found that clinicians with less than 10 years of experience were significantly more likely to use social media than clinicians with more years of experience.14 In the more recent study during the pandemic, this difference was no longer significant. This change may represent a shifting trend where the enhanced role of electronic communications in daily life, combined with telecare, led clinicians who had previously not considered using electronic media as a source of digital collateral information, to start to include it in their sessions.

We also found that, during the pandemic, significantly more clinicians relied on patients’ self-report as a method for reviewing their electronic media than before the pandemic. In the pre-pandemic wave, the most common method of reviewing social media was in the patients’ presence. This change represents the fact that virtual care made it harder to view electronic media platforms directly in the patient’s presence. Indeed, it would have required patients to take many extra steps, such as sharing screens via Zoom, sending screenshots, forwarding emails, etc, which might have been more difficult for certain patients such as older adults with lower digital literacy.16 This also likely explains our findings that more patients initiated discussions about privacy during the pandemic than before. This is consistent with findings that a primary concern about sharing electronic information, or using digital mental health tools in general, is data security and privacy.12,17 Furthermore, evidence suggests that the pandemic has heightened awareness and concern among Americans about privacy and personal data on social media and in telemedicine.18–21

We found that the percentage of clinicians using electronic media in therapy rose from 66% before the pandemic to 89% during the pandemic, with a trend toward an increase in clinicians reporting viewing media of older adult patients. Although not significant, these findings may indicate changes in clinicians’ habits. In addition, with telemedicine retaining its use for psychotherapy 3 years into the pandemic (at the time of writing), clinicians are likely to continue to explore digital sources of collateral information to augment clinical assessment. Our work is also consistent with recent data indicating that collection and incorporation of digital data into therapy is feasible, although questions remain about how exactly the use of such digital data impacts outcomes.6

We found that most clinicians who reported using electronic media infrequently in their therapy practice were more likely to review clients’ SMS texting and email data. This is consistent with what clinicians reported before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2018. While data from electronic media may be useful for detecting trends in psychotherapy at the population level22 or to predict distinct events,22 the more personal nature of text or email communication may be more meaningful. This finding is consistent with other studies that have found that text communication may reflect interpersonal communication dynamics, the understanding of which is integral to psychotherapy.10

There are several caveats concerning our findings. We acknowledge the time gap between data collection and manuscript preparation, but believe that practice changes captured by our data have consolidated in the intervening time period. The participants in this study were all recruited from the same psychiatric institution (McLean Hospital). Although they varied in terms of their clinical backgrounds and degrees, our results may not be generalizable, given that the study was conducted in a tertiary care setting. Similarly, the patients receiving treatment by the providers that participated in this study might not be representative of patient populations at large. Our survey was anonymous and brief, so we did not collect substantial demographic details concerning our participants or their patients. This limited our ability to do a more detailed analysis on specific patient populations. Our survey did not have specific questions assessing the use of apps to track patients’ sleep, mindfulness practices, physical activity, mood, habits, and behavior. These apps could also be a rich source of collateral information. We were also unable to assess responders’ bias as we did not ask for specific demographic information and therefore could not compare responders with non-responders. Our study did not delve into specifics of how clinicians utilized information from digital media. Future work should build on our findings by focusing on the mechanistic basis of how this information impacts outcomes. Moreover, our study findings represent electronic media access by clinicians in the early stages of the pandemic. While trends in the use of telemedicine for psychotherapy increased at the start of the pandemic and both patients and providers became more comfortable with this new platform,23 it is possible that patterns of digital collateral information use have evolved since the time of the survey. Our data do not capture these trends and they merit study in future work.

Despite these limitations, our study contributes to understanding how the pandemic has changed the use of electronic and digital media platforms in the context of psychotherapy. Our study also highlights issues that patients might have regarding the use of technology in psychotherapy, such as privacy. Technology has given us new ways of gathering collateral information and provides new ways to do this, and the pandemic has increased our use of digital platforms to communicate with others and get treatment. Media can be a rich source of collateral information to inform psychotherapy, and more research is needed to fully understand the impact it can have on specific types of psychotherapy and in more diverse clinical settings.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Once Upon a Time Foundation

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Ressler has performed scientific consultation for Bioxcel, Bionomics, Acer, Takeda, and Jazz Pharma and serves on Scientific Advisory Boards for Sage and the Brain Research Foundation; he has received sponsored research support from Takeda, Brainsway and Alto Neuroscience. None of this work is related to the current study. Dr. Vahia receives current research support from the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Mental Health, the Once Upon a Time Foundation, and the Harvard Dean’s Initiative on Aging. Dr. Ressler was previously an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and receives current research support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Once Upon a Time Foundation. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Ipsit V. Vahia, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA; Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Rachel Sava, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA.

Hailey V. Cray, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA.

Heejung J. Kim, Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine, Nova Southeastern University, Ft Lauderdale, FL

Rebecca A. Dickinson, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA

Kerry J. Ressler, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA; Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Ana F. Trueba, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA; Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Department of Psychology, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

REFERENCES

- 1.Digital Kemp S. 2020: Global Digital Overview. DataReportal; January 30, 2020. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview. Accessed June 17, 2022.

- 2.Drouin M, McDaniel BT, Pater J, et al. How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2020;23:727–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogels EA, Perrin A, Rainie L, et al. 53% of Americans say the internet has been essential during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech; April 30, 2020. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/04/30/53-of-americans-say-the-internet-has-been-essential-during-the-covid-19-outbreak/. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- 4.Hankoff LD. Denial of illness in schizophrenic outpatients: effects of psychopharmacological treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1960;3:657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawver T A Proposal for including patient-generated web-based creative writing material into psychotherapy: advantages and challenges. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2008;5:56–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merchant RM, Southwick L, Beidas RS, et al. Effect of integrating patient-generated digital data into mental health therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv 2022 Dec 22:appips20220272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.20220272. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guntuku SC, Ramsay JR, Merchant RM, et al. Language of ADHD in adults on social media. J Atten Disord 2019;23:1475–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coppersmith G, Dredze M, Harman C. Quantifying mental health signals in Twitter. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology: From Linguistic Signal to Clinical Reality. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2014:51–60. Available at: https://aclanthology.org/W14-3207.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2022.

- 9.Hoogendoorn M, Berger T, Schulz A, et al. Predicting social anxiety treatment outcome based on therapeutic email conversations. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2017;21:1449–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swartz HA, Novick DM. Psychotherapy in the digital age: what we can learn from interpersonal psychotherapy. Am J Psychother 2020;73:15–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.20190040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Matteo D, Fine A, Fotinos K, et al. Patient willingness to consent to mobile phone data collection for mental health apps: structured questionnaire. JMIR Ment Health 2018;5:e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieger A, Gaines A, Barnett I, et al. Psychiatry outpatients’ willingness to share social media posts and smartphone data for research and clinical purposes: survey study. JMIR Form Res 2019;3:e14329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deen SR, Withers A, Hellerstein DJ. Mental health practitioners’ use and attitudes regarding the internet and social media. J Psychiatr Pract 2013;19:454–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hobbs KW, Monette PJ, Owoyemi P, et al. Incorporating information from electronic and social media into psychiatric and psychotherapeutic patient care: survey among clinicians. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e13218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson M, Vogels EA. Americans turn to technology during COVID-19 outbreak, say an outage would be a problem. Pew Research Center; March 31, 2020. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/31/americans-turn-to-technology-during-covid-19-outbreak-say-an-outage-would-be-a-problem. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- 16.Schreurs K, Quan-Haase A, Martin K. Problematizing the digital literacy paradox in the context of older adults’ ICT use: aging, media discourse, and self-determination. Can J Commun 2017;42:359–377. doi: 10.22230/cjc.2017v42n2a3130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torous J, Wisniewski H, Liu G, et al. Mental health mobile phone app usage, concerns, and benefits among psychiatric outpatients: comparative survey study. JMIR Ment Health 2018;5:e11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Auxier B How americans see digital privacy issues amid the COVID-19 outbreak. Pew Research Center; May 4, 2020. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/04/how-americans-see-digital-privacy-issues-amid-the-covid-19-outbreak/. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- 19.Brohi SN, Jhanjhi N, Brohi NN et al. Key Applications of state-of-the-art technologies to mitigate and eliminate COVID-19. TechRxiv2020. Preprint 10.36227/techrxiv.12115596.v2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lallie HS, Shepherd LA, Nurse JRC, et al. Cyber security in the age of COVID-19: A timeline and analysis of cyber-crime and cyber-attacks during the pandemic. Computers & Security 2021;105:102248. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2021.102248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shachar C, Engel J, Elwyn G. Implications for telehealth in a postpandemic future: regulatory and privacy issues. JAMA 2020;323:2375–2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torous J, Bucci S, Bell IH, et al. The growing field of digital psychiatry: current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry 2021;20:318–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu D, Paige SR, Slone H, et al. Exploring telemental health practice before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J Telemed Telecare Jul 9:1357633X211025943. doi: 10.1177/1357633X211025943. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]