Abstract

Introduction

Beta-blockers (BB) and renin angiotensin system inhibitors (RASi) are foundational for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). However, given the increased risk of side effects in older patients, uncertainly remains as to whether, on net, older patients benefit as much as the younger patients studied in trials.

Methods

Using the GWTG-HF registry linked with Medicare data, overlap propensity weighted Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine the association between BB and RASi use at hospital discharge 30-day and 1-year outcomes among patients with HFrEF.

Results

Among the 48,711 patients (age ≥65 years) hospitalized with HFrEF, there were significant associations between BB and/or RASi use at discharge and lower rates of 30-day and 1-year mortality, including those over age 85 (30-day HR=0.56 [95% CI 0.45, 0.70]; 1-year HR=0.69 [95% CI 0.61, 0.78]). In addition, the magnitude of benefit associated with BB and/or RASi use after discharge did not decrease with increasing age. Even among the oldest patients, those over age 85, with hypotension, renal insufficiency or frailty, BB and/or RASi at discharge was still associated with lower 1-year mortality or readmission.

Conclusions

Among older patients hospitalized with HFrEF, BB and/or RASi use at discharge is associated with lower rates of 30-day and 1-year mortality across all age groups and the magnitude of this benefit does not appear to decrease with increasing age. These data suggest that, absent a clinical contraindication, BB and RASi should be considered in all patients hospitalized with HFrEF before or at hospital discharge, regardless of age.

Lay Summary

• Beta-blockers (BB) and renin angiotensin system inhibitors (RASi) are key treatments for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); however, like all drugs, they have side effects and it is unknown whether the risk of side effects outweigh the benefits of these drugs in older patients with HFrEF.

• Using data from the American Heart Association linked with Medicare claims we examined the association between drug use and death rates 30 days and 1 year after hospitalization in over 48,000 patients with HFrEF.

• BB and/or RASi use is associated with lower rates of 30-day and 1-year death rates across all age groups and the benefit of these drugs for patients with HFrEF does not appear to decrease with increasing age, suggesting that absent a contraindication, these drugs should be prescribed for all patients with HFrEF, regardless of age.

Introduction

Beta-blockers (BB) and renin angiotensin system inhibitors (RASi) are foundational to the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).1–3 Both BB and RASi have demonstrated mortality and morbidity benefits in randomized trial settings, but older patients, now the majority of HFrEF patients, were underrepresented in those original trials.2–5

The average age of a patient enrolled in the early BB and RASi trials was 50–60 years old and the patients had comparatively few comorbidities.2–5 Today, the average patient with HFrEF is 75 years old.6 By 2030, the American Heart Association projects that heart failure prevalence will rise by as much as 46%.7 When combined with increasing life expectancies, this will result in an older, more comorbid and increasingly frail8 heart failure population that may be at higher risk of side effects to BB and RASi that could counterbalance some of the benefits of standard therapy. As a result, there remains clinical uncertainty as to whether the benefits of BB and RASi in older patients with HFrEF are as large in older patients as they are in younger patients and whether, on net, these benefits of therapy outweigh the potential risks in older populations.

Unfortunately, clinical trial data in this population is limited3,5,9,10 and it is unlikely that a randomized trial will ever be conducted to answer this question. Therefore, given the increasing prevalence of HFrEF among older adults, in this analysis we use national registry data from the Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry linked with Medicare claims to determine if the associations between BB and/or RASi use after HFrEF hospitalization and HF outcomes (including death, readmission and death or readmission) vary across the age spectrum. In addition, we examine these associations among three, pre-determined subgroups commonly thought to be at higher risk for BB/RASi side effects, namely those with hypotension, renal insufficiency and frailty.

Methods

Data Source

Data for this analysis are from the Get With The Guidelines Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry linked with Medicare inpatient data. Medicare Part A (inpatient) claims and the associated denominator file from January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2017 were linked with data from the GWTG-HF registry using previously described methods and indirect identifiers.11 GWTG-HF is a hospital-based, voluntary data collection and quality improvement initiative that began in 2005. Linkage of GWTG-HF data with Medicare claims data allows for both short- and long-term mortality and readmission assessment.

Study Population

Patients were eligible to be included if they were ≥65 years of age and admitted to fully-participating GWTG-HF hospitals between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2016 with a principal diagnosis of heart failure. Analysis was restricted to sites reporting the medical history panel for ≥75% of patients (495 sites). Patients for whom age or sex and all past medical history were missing in the data were excluded. For patients missing some, but not all, variables, multiple imputation was used (Appendix 1). If multiple hospitalizations existed for a patient, only the first hospitalization was kept as the index hospitalization. Patients with ejection fractions >40%, those who died during index hospitalization, were not fee-for-service eligible at discharge, had missing drug use data at discharge or had contraindications listed for both BB and RASi were excluded. Patients from hospitals with only treated or only untreated patients were also excluded. A complete consort diagram is detailed in Appendix 2.

Exposure(s)

Using eligible patients without a documented contraindication to BB and RASi therapy, we created 4 patient groups:

Those discharged on BB + RASi

Those discharged on RASi-only

Those discharged on BB-only

Those discharged on neither BB nor RASi

In primary analyses, patients in groups 1–3 are considered “treated” patients and group 4 is considered “untreated” patients. In order to be considered “on a BB” only HF-specific BB were considered: metoprolol succinate, carvedilol and bisoprolol.

Outcomes(s)

The primary endpoints of this study were the differences in 30-day all-cause and 1-year mortality between treated and untreated patients. The secondary endpoints were the difference between treated and untreated patients in 30-day and 1-year readmissions and a composite of mortality or readmissions. Outcomes were examined overall and then by age subgroup: 65–74 years, 75–84 years and 85+ years. Prespecified subgroup analyses included patients with:

Hypotension, defined as a discharge blood pressure <110mmHg12,13

Renal insufficiency, defined as a discharge creatinine ≥2mg/dL14

Frailty, defined as a Hospital Frailty Risk Score ≥5. This methodology was developed by Gilbert et. al. in 2018 and uses International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnostic codes in inpatient claims data to determine frailty.15 Model discrimination between individuals for mortality (c-statistic=0.60), prolonged hospitalization (c=0.65) and readmission (c=0.56) is good. In addition, the model demonstrates fair overlap with dichotomized Fried16 (kappa=0.22, 95% CI=0.15–0.30) and Rockwood17–19 (kappa=0.30, 95% CI=0.22–0.38) and moderate agreement with the Rockwood Frailty Index18,19 (Pearson’s correlation coefficient 0.41, 95% CI=0·38–0·47).

Overlap Propensity Weighting

To address all measurable confounding, we fit a propensity model for likelihood to receive BB or RASi using the covariates detailed in Appendix 3. All analysis models were then run with treatment groups balanced using overlap propensity weighting.20 Overlap propensity weighting was chosen because it allows patients to influence the analysis more the closer to 0.5 their propensity scores are, i.e. the more discretionary their treatment is. The primary virtue of overlap weighing compared to other propensity score weighting schemes is that it minimizes the standard error of the resulting estimated effect of treatment.20,21 Covariate balance was checked overall and in each subgroup, by age. The excellent balance of covariates after overlap weighting is shown in Appendix 4.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized using standard descriptive statistics and differences between groups were quantified with p-values and standardized differences. Variables with missing data were not imputed in descriptive tables. For model covariates, missing medical history was imputed to “No” and discharge vitals were imputed to admission values when available. Hospital characteristics were not imputed. For other covariates, multiple imputation with ten datasets was conducted. Propensity score and outcome analysis models were run on each imputed dataset, and results were aggregated using Rubin’s rules.

The association between the clinical outcomes and treatment with BB/RASi was assessed using a Cox proportional hazards model. Unweighted and weighted hazard ratios were calculated with overlap weights. All models were adjusted for admission year, age group and the interaction of treatment by age group. Within-hospital clustering was accounted for using the robust sandwich covariance estimate. Overlap-weighted Kaplan-Meier incidence curves for 1-year mortality or readmission, comparing treated and untreated patients in each age strata were also drawn.

As a supplementary analysis, Cox regression models including a 4-level treatment group (RASi+BB, BB-only, RASi-only and neither treatment) were fit, and adjusted for the same covariates used in the propensity score models. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R software (version 3.4.3, R Core Team) and two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered significant for all statistical tests.

All participating institutions are required to comply with local regulatory and privacy guidelines and to submit the GWTG protocol for review and approval by their institutional review board. Because data are used mainly at the local site for quality improvement, sites were granted a waiver of informed consent under the common rule. The Duke Clinical Research Institute served as the primary analytic center for the aggregate de-identified data. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center and the Duke University.

Results

Baseline characteristics for the 48,711 patients included in these analyses are detailed in Table 1 (additional detail provided in Appendix 5a). There are 47,299 treated patients who received BB and/or RASi at hospital discharge and 1,412 untreated patients who received neither BB nor RASi at discharge. The average age of treated patients was 79 years compared to 82 among untreated patients. Forty one percent of treated patients ad 40% of untreated patients were women.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Stratified by Discharge Treatment Status

| Overall | Treated Patients BB and/or RASi | Untreated Patients No BB or RASi | P-Value | Absolute Std. Diff (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=48,711) | (N=47,299) | (N=1,412) | |||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years | 79.0 (72.0–85.0) | 79.0 (72.0–85.0) | 82.0 (74.0–88.0) | <.0001 | 29.79 |

| Female Sex | 19,769 (40.6%) | 19,204 (40.6%) | 565 (40.0%) | 0.658 | 1.2 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 38,248 (80.1%) | 37,122 (80.0%) | 1,126 (82.1%) | ||

| 0.0324 | 7.49 | ||||

| Black | 5,518 (11.6%) | 5,390 (11.6%) | 128 (9.3%) | ||

| Other | 3,983 (8.3%) | 3,865 (8.3%) | 118 (8.6%) | ||

| Median household income* | $52,756 (46,338–62,936) | $52,765 (46,335–62,936) | $52,646 (46,484–62,938) | 0.9175 | 1.31 |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| % < high school diploma | 11.8 (9.2–15.1) | 11.8 (9.2–15.1) | 12.4 (9.6–15.6) | 0.0022 | 6.85 |

| % high school diploma or higher | 88.2 (84.9–90.8) | 88.2 (84.9–90.8) | 87.6 (84.4–90.4) | 0.0022 | 6.85 |

| % college 4+yrs or higher | 28.0 (20.4–35.0) | 28.0 (20.4–35.0) | 27.7 (20.4–34.7) | 0.6586 | 1.55 |

| Medical History | |||||

| Hypertension | 34,816 (77.2%) | 33,872 (77.4%) | 944 (72.0%) | <.0001 | 12.32 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 24,828 (55.1%) | 24,164 (55.2%) | 664 (50.6%) | 0.0011 | 9.1 |

| Afib/flutter | 18,336 (40.7%) | 17,752 (40.5%) | 584 (44.5%) | 0.0036 | 8.11 |

| Diabetes | 17,995 (39.9%) | 17 557 (40.1%) | 438 (33.4%) | <.0001 | 13.82 |

| Ischemic etiology | 29,303 (65.0%) | 28,539 (65.2%) | 764 (58.3%) | <.0001 | 14.23 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 9,276 (20.6%) | 8,935 (20.4%) | 341 (26.0%) | <.0001 | 13.31 |

| End Stage Renal Disease | 2,333 (4.8%) | 2,221 (4.7%) | 112 (7.9%) | <.0001 | 13.34 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 26,298 (58.3%) | 25,612 (58.5%) | 686 (52.3%) | <.0001 | 12.43 |

| Cancer | 3,737 (7.7%) | 3,589 (7.6%) | 148 (10.5%) | <.0001 | 10.11 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 12,007 (26.6%) | 11,706 (26.7%) | 301 (23.0%) | 0.0023 | 8.74 |

| Prior Stroke/TIA | 7,407 (16.4%) | 7,199 (16.4%) | 208 (15.9%) | 0.5799 | 1.56 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 6,047 (13.4%) | 5,867 (13.4%) | 180 (13.7%) | 0.7287 | 0.97 |

| Smoker | 5,331 (11.0%) | 5,211 (11.1%) | 120 (8.6%) | 0.0038 | 8.27 |

| COPD or asthma | 12,277 (27.2%) | 11,860 (27.1%) | 417 (31.8%) | 0.0002 | 10.38 |

| Dementia | 3,666 (7.5%) | 3,511 (7.4%) | 155 (11.0%) | <.0001 | 12.32 |

| ICD or CRT device | 9,897 (21.9%) | 9,678 (22.1%) | 219 (16.7%) | <.0001 | 13.68 |

| Frail (score >≥5) | 5,867 (12.4%) | 3,535 (10.8%) | 2,332 (16.0%) | <0.001 | 15.41 |

| Admission Characteristics | |||||

| Ejection fraction | 30.0 (21.0–35.0) | 29.0 (20.0–35.0) | 33.0 (24.0–40.0) | <.0001 | 32.61 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 83.0 (72.0–98.0) | 83.0 (72.0–98.0) | 84.0 (71.0–99.0) | 0.8482 | 0.63 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | 135.0 (118.0–153.0) | 135.0 (118.0–154.0) | 128.0 (113.0–144.0) | <.0001 | 29.02 |

| Rales | 8,745 (47.1%) | 8,499 (47.1%) | 246 (46.2%) | 0.3698 | 0.58 |

| Jugular venous distention | 4,419 (24.0%) | 4,308 (24.1%) | 111 (21.2%) | 0.0583 | 4.85 |

| Lower extremity edema | 11,220 (60.4%) | 10,879 (60.3%) | 341 (64.1%) | 0.0669 | 9.63 |

| Creatinine | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | <.0001 | 1.97 |

| Sodium | 138.0 (136.0–141.0) | 138.0 (136.0–141.0) | 138.0 (136.0–141.0) | 0.6989 | 3.94 |

| Potassium | 4.2 (3.8–4.6) | 4.2 (3.8–4.6) | 4.2 (3.8–4.6) | 0.8274 | 0.93 |

| B-type Natriuretic Peptide, pg/mL | 1128 (590.0–2123) | 1126 (589.0–2123) | 1180 (617.3–2076) | 0.3489 | 5.41 |

| Troponin | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.0549 | 0.99 |

| GDMT at Admission | |||||

| On RASi at admission | 12,437/48,711 (25.5%) | 12,331/47,299 (26.1%) | 106/1,412 (7.5%) | <.0001 | 82.16 |

| On BB at admission | 16,713/48,711 (34.3%) | 16,573/47,299 (35.0%) | 140/1,412 (9.9%) | <.0001 | 111.85 |

| MRA at admission | 2,614/48,711 (5.4%) | 2,544/47,299 (5.4%) | 70/1,412 (5.0%) | 0.7634 | 1.18 |

| Any NHT at admission | 19,463/48,711 (40.0%) | 19,261/47,299 (40.7%) | 202/1,412 (14.3%) | <.0001 | 118.30 |

| Discharge Characteristics | |||||

| Heart rate, bpm | 76.0 (67.0–86.0) | 76.0 (67.0–86.0) | 78.0 (69.0–89.0) | 0.0001 | 10.82 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | 118.0 (106.0–132.0) | 118.0 (106.0–132.0) | 117.0 (104.0–131.0) | 0.0153 | 7.25 |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen | 28.0 (20.0–40.0) | 28.0 (20.0–40.0) | 30.0 (21.0–46.0) | 0.0002 | 18.78 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | <.0001 | 1.3 |

| eGFR | 50.2 (35.0–68.3) | 50.2 (35.2–68.3) | 46.5 (29.2–64.6) | <.0001 | 18.09 |

| Sodium | 138.0 (136.0-, Ί.0) | 138.0 (136.0–141.0) | 138.0 (136.0–141.0) | 0.6747 | 0.76 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.1 (3.8–4.4) | 4.1 (3.8–4.4) | 4.1 (3.7–4.4) | 0.5115 | 4.99 |

| B-type Natriuretic Peptide, pg/mL | 966.0 (472.0–1856) | 962.0 (471.0–1850) | 1069 (518.1–2009) | 0.0494 | 12.58 |

| LOS, days | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 0.2121 | 7.36 |

| Discharge disposition | <.0001 | 28.77 | |||

| Home | 37,175 (76.3%) | 36,276 (76.7%) | 899 (63.7%) | ||

| Other Facility | 11,536 (23.7%) | 11,023 (23.3%) | 513 (36.3%) | ||

| Hospital Characteristics | |||||

| Geographic Region | |||||

| Northeast | 14,444 (29.7%) | 14,030 (29.7%) | 414 (29.3%) | ||

| Midwest | 11,753 (24.1%) | 11,420 (24.1%) | 333 (23.6%) | 0.7682 | 2.87 |

| South | 17,140 (35.2%) | 16,625 (35.1%) | 515 (36.5%) | ||

| West | 5,374 (11.0%) | 5,224 (11.0%) | 150 (10.6%) | ||

| Academic/Teaching Hospital | 36,715 (77.2%) | 35,705 (77.3%) | 1,010 (73.8%) | 0.0028 | 8.02 |

| Number of Beds | 383.0 (248.0–571.0) | 383.0 (248.0–571.0) | 376.0 (230.0–556.0) | 0.0087 | 7.98 |

| Rural Location | 1,896 (4.1%) | 1,827 (4.0%) | 69 (5.1%) | 0.048 | 5.17 |

Indexed using CPI-U 2016 average, US Dollars ($)

Afib is atrial fibrillation; TIA is transient ischemic attack; COPD is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICD is implanted cardiac defibrillator; CRT is cardiac resynchronization therapy; LOS is length of stay; GDMT is guideline directed medical therapy; MRA is mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NHT is neurohormonal therapy

Treatment rates by age group are described in Appendix 5b. The average age of patient with HFrEF was 79 years (25th, 75th quantile: 72, 85 years). Among treated patients, the average age was 79 years (25th, 75th quantile: 72, 85 years) and among untreated patients the average age was 82 years (25th, 75th quantile: 74, 88 years). Approximately 40% of patients in both the treated and untreated group were female. Patients identifying as black comprised 12% of treated patients and 9% of untreated patients. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (77% overall, 77% treated, 72% untreated) and ischemic disease (65% overall; 65% treated; 58% untreated). Chronic kidney disease was present in 21% of patients overall (20% treated, 26% untreated) and 5% had end stage renal disease (5% treated, 8% untreated). Among treated patients, 11% had frailty scores ≥5; among untreated patients, 16% had frailty scores frailty scores ≥5, suggesting clinically significant frailty.15

At admission, the median ejection fraction was 30% (29% treated, 33% untreated), median systolic blood pressure was 135mmHg (135mmHg treated, 128mmHg untreated) and median creatinine was 1.3mg/dL (1.3 mg/dL treated, 1.4mg/dL untreated, Table 1). Before weighting treatment prior to admission was unbalanced: among treated patients 69% were receiving BB therapy and 51% were receiving RASi therapy; among untreated patients, 21% were receiving BB therapy and 16% were receiving RASi therapy. At discharge, the median systolic blood pressure was 118mmHg (118mmHg treated, 117 untreated), median creatinine was 1.3mg/dL (1.3mg/dL treated, 1.4mg/dL untreated). Twenty-four percent of all patients were discharged to post-acute care (23% treated, 36% untreated). Hospital characteristics were similar across treatment groups.

Event rates, by age group, are displayed in Table 2. Overall, 6% died within 30 days and 34% died within 1 year of discharge. Almost 22% were readmitted within 30 days and 64% were readmitted within 1 year. Clinical event rates were highest among patients aged 85 and older. Their 30-day mortality rate 9%, compared to 3% and their 1-year morality was 46% compared to 25% among those aged 65–74 years old.

Table 2.

Event Rates, by Age Group

| Overall (n=48,711) | 65–74 yrs old (n=16,095) | 75–84 yrs old (n=18,525) | 85+ yrs old (n=14,091) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| 30-day all-cause mortality | 2,806 (5.8%) | 549 (3.4%) | 976 (5.3%) | 1,281 (9.1%) |

| 1-year all-cause mortality | 16,678 (34.2%) | 3,980 (24.7%) | 6,175 (33.3%) | 6,523 (46.3%) |

| All-cause readmission | ||||

| 30-day all-cause readmission | 10,640 (21.8%) | 3,534 (22.0%) | 4,087 (22.1%) | 3,019 (21.4%) |

| 1-year all-cause readmission | 31,066 (63.8%) | 10,256 (63.7%) | 12,057 (65.1%) | 8,753 (62.1%) |

| All-cause mortality or readmission | ||||

| 30-day all-cause mortality or readmission | 12,071 (24.8%) | 3,779 (23.5%) | 4,574 (24.7%) | 3,718 (26.4%) |

| 1-year all-cause mortality or readmission | 34,903 (71.7%) | 10,936 (67.9%) | 13,293 (71.8%) | 10,674 (75.8%) |

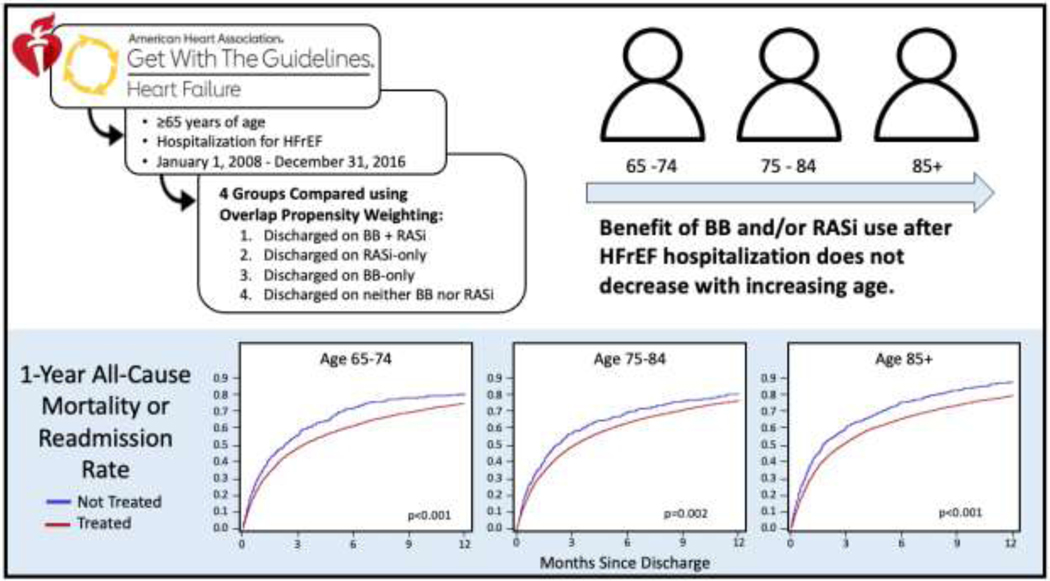

Unweighted and weighted hazard ratios, by age group, comparing treated and untreated patients are displayed in Table 3. Even after weighting, BB and/or RASi use was associated with lower 30-day all-cause mortality (Age 65–74: HR=0.42 [95% CI 0.28, 0.62]; Age 75–84: HR=0.48 [95% CI 0.36, 0.63)]; Age 85+: HR=0.57 [95% CI 0.46, 0.71]) and there was no difference in the magnitude of associated benefit across the age spectrum, interaction p-value 0.686. In addition, treatment was also associated with lower 1-year all-cause mortality in each age group (Age 65–74: hazard ratio [HR] 0.65 [95% CI 0.54, 0.79]; Age 75–84: HR=0.79 [95% CI 0.68, 0.91)]; Age 85+: HR=0.69 [95% CI 0.61, 0.78]) and again, there was no difference in the magnitude of effect across the different age groups, interaction p-value 0.264. Weighted Kaplan-Meier curves for 1-year mortality or readmission, by age group, are shown in Figure 1 (individual Kaplan-Meier curves for 1-year mortality, readmission and mortality or readmission in treated vs. untreated patients, by age group are included in Appendix 6).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Hazard Ratios for 1-year and 30-day Mortality or Readmission, by Age Group

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Interaction P-value | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Interaction P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=48,711) | (N=45,201) | |||

| 30-day all-cause mortality | ||||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 65–74 | 0.31 (0.21, 0.45) | 0.289 | 0.42 (0.28, 0.62) | 0.284 |

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 75–84 | 0.39 (0.30, 0.51) | 0.48 (0.36, 0.63) | ||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 85+ | 0.43 (0.35, 0.53) | 0.57 (0.46, 0.71) | ||

| 1-year all-cause mortality | ||||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 65–74 | 0.50 (0.41, 0.60) | 0.114 | 0.65 (0.54, 0.79) | 0.264 |

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 75–84 | 0.63 (0.55, 0.72) | 0.79 (0.68, 0.91) | ||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 85+ | 0.57 (0.50, 0.64) | 0.69 (0.61, 0.78) | ||

| 30-day all-cause readmission | ||||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 65–74 | 0.69 (0.56, 0.84) | 0.395 | 0.88 (0.70, 1.09) | 0.856 |

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 75–84 | 0.82 (0.68, 0.99) | 0.92 (0.76, 1.12) | ||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 85+ | 0.79 (0.68, 0.92) | 0.85 (0.72, 1.01) | ||

| 1-year all-cause readmission | ||||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 65–74 | 0.68 (0.59, 0.79) | 0.109 | 0.83 (0.71, 0.97) | 0.630 |

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 75–84 | 0.81 (0.73, 0.89) | 0.90 (0.82, 1.00) | ||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 85+ | 0.81 (0.73, 0.90) | 0.86 (0.77, 0.95) | ||

| 30-day all-cause mortality or readmission | ||||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 65–74 | 0.64 (0.53, 0.77) | 0.719 | 0.80 (0.65, 0.99) | 0.686 |

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 75–84 | 0.70 (0.60, 0.83) | 0.80 (0.67, 0.95) | ||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 85+ | 0.65 (0.57, 0.75) | 0.72 (0.62, 0.84) | ||

| 1-year all-cause mortality or readmission | ||||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 65–74 | 0.67 (0.58, 0.78) | 0.502 | 0.81 (0.70, 0.95) | 0.437 |

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 75–84 | 0.74 (0.67, 0.82) | 0.85 (0.77, 0.94) | ||

| Treated vs. Untreated, age 85+ | 0.71 (0.64, 0.78) | 0.77 (0.70, 0.85) | ||

Treated: received BB+RASi, BB-only or RASi-only at hospital discharge; Untreated: received neither BB nor RASi at hospital discharge

(Figure 1). Central Illustration :

Overlap-weighted Cumulative Incidence Curves of 1-year Mortality or Readmission in Treated vs. Untreated Patients, by Age Group

Additional unadjusted and regression-adjusted hazard ratios, by age group, comparing all 4 groups: BB+RASi, BB-only, RASi-only and untreated patients are included in Appendix 7. BB-only use and RASi-only use are both associated with a trend toward lower 30-day and 1year mortality and/or readmission compared to no treatment, but the finding is only significant in the oldest age group (where rates of BB-only use and RASi-only use are proportionally higher). Finally, to address safety, we compared the cumulative incidence of readmission for acute kidney injury, bradycardia, hyperkalemia and hypotension and found no significant difference between treated and untreated patients (Appendix 8).

Hypotension Subgroup

Among patients with a discharge systolic blood pressure <110mmHg (n=15,323; 31% of the overall sample), 27% experienced either mortality or readmission within 30 days after index admission and 74% did so within 1 year after index admission;. In weighted analysis, treatment with BB and/or RASi was significantly associated with a lower risk of 30-day and 1-year mortality or readmission among those aged 75 and older (Figure 2a).

Figure 2 a/b/c.

Hypotension, Renal Insufficiency and Frailty Subgroups

Renal Insufficiency Subgroup

Among patients with a discharge creatinine ≥2mg/dL (n=10,404; 21% of the overall sample), 30% experienced either mortality or readmission within 30 days after index admission while 81% did so within 1 year after admission. In weighted analysis, treatment with BB and/or RASi was associated with a significant decrease in 30-day and 1-year mortality or readmission and readmission only among those aged 85 and older (Figure 2b).

Frailty Subgroup

Among patients with a frailty score ≥5 (n=6,166, 12% of the overall sample), 29% experienced either mortality or readmission within the first 30 days after discharge and 77% experienced it within 1 year. Treatment with BB and/or RASi was associated with a lower rate of 1-year mortality or readmission only among those 85 and older. There was no significant association with 30-day mortality or readmission in any of the age groups (Figure 2c).

Discussion

Using national registry data linked with Medicare claims, these results confirm that BB and/or RASi use at hospital discharge, among eligible patients, is associated with improved 30-day and mortality, regardless of age. The use of BB and/or RASi at hospital discharge is associated with a similar benefit for older patients (aged 85+) compared to younger patients (aged 65–74). Among the oldest patients, those aged 85+, BB and/or RASi used is associated with lower 1-year mortality, even in populations traditionally “high risk” for BB and/or RASi therapy, including those with hypotension, renal insufficiency and frailty.

These results are particularly important in light of limited prior clinical trial data and the fact that a randomized trial focused on this older populations is unlikely to ever be conducted. Prior clinical trial data is limited by age cutoffs, subgroup sample size and BB choice. For example, subgroup analyses of MERIT-HF, CIBIS-II and the early Carvedilol studies, suggested a benefit in older populations, but “older” was defined as ≥65 years and the subgroups were underpowered.3,5,9 In 2005, the SENIORS trial demonstrated a modest benefit for nebivolol, notably not a HF-specific beta-blocker.10 In 2000 Flather et. al. combined data from 5 randomized trails and found a benefit for ACEi in younger patients with left-ventricular dysfunction or heart failure, but for patients over age 75, the results were not significant.22

Given the limitations of prior clinical trial subgroup analyses, recent work has attempted to address this question using retrospective, national claims data. In a recent analysis using Medicare claims for over 300,000 beneficiaries admitted with HFrEF between 2008 and 2015, approximately half of which were over age 80, the authors found significant associations between BB and RASi use after HFrEF hospitalization lower 30-day and 1-year mortality rates.23 This study was limited by its retrospective design and the possibility of unmeasured confounding so a subsequent study employed an instrumental variable approach to address the unmeasured confounding and found a similar benefit, though only BB use was exmined.24 The results of this study confirm and extend prior findings. Specifically, they confirm the associated benefit of BB and/or RASi use at hospital discharge in HFrEF across all age groups suggested by prior trial subgroup analysis, but do so with a much larger sample sizes, particularly among the oldest patients.5,9 Building on prior retrospective work as well, this study adds the granularity of registry data and employs a more sophisticated weighting methodology to address potential confounding.

In addition, this study was able to consider three, a priori defied subgroups of patients commonly thought to be at “high risk” for side effects to BB and/or RASi, namely those with hypotension, renal insufficiency and frailty.25 While the power is limited by the smaller sample sizes of subgroup analyses, BB and/or RASi use was associated with lower 1-year mortality rates among the oldest patients, those age 85 and older, despite hypotension, renal insufficiency and frailty. These results are interesting and may merit additional examination.

Moreover, additional work is needed to examine the association between BB and RASi use among older adults and HF readmissions only. In addition, the associations between mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), SGLT-2 inhibitor, vericiguat and ivabradine use and short/long-term outcomes and determine whether these associations vary across the age spectrum merit further study. MRA’s were not able to be considered in this study due to insufficient numbers and the time period was not appropriate for examination of newer therapies. In addition, additional work is need to further explore subgroups. Our analysis was limited to the cutoffs of systolic blood pressure <110mmHg and creatinine <2mg/dL by sample size and power but larger analyses could explore the association between BB and/or RASi use in groups with lower systolic pressures and higher creatinine levels. Finally, additional work could explore the association between of “new start” vs. “continuation” of therapy or “never started” vs. “discontinuation” of therapy in older populations.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted within the context of their limitations. First, due to the retrospective design of this study, we are unable to draw any conclusions regarding causation. Second, because the data from this study comes from a national registry of voluntarily participating hospitals which individually input data, and the analysis was restricted to sites that reported medical history for ≥75% of patients, the findings may not generalize to those where there are substantial differences from the population included. The results should be interpreted within the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria and caution should be used when extrapolating these results to patient groups not adequately included/represented in this analysis. Thirdly, while we used clinical data and overlap propensity weighting to balance exposed and unexposed patients, it is possible that some of the association(s) we observe are impacted by unmeasured confounding. There are many chronic and acute conditions including social determinants of health that impact both medication prescribing and outcomes that we may not be able to completely capture in our data. Fourthly, given the years of data in this study (through 2017) ARNI’s are under-utilized in this population and this could have more important impact on subgroup analyses. Future work should consider this. Moreover, we do not have information about dose, why a drug was not prescribed nor are we able to track drug use over time and thus the interpretation of these results is limited to the association between drug use at hospital discharge and outcome, although reflecting the clinicians’ intention to treat.

Conclusions

Among all patients aged 65 years and older hospitalized for HFrEF, including those age 85 and older, BB and/or RASi use at discharge is associated with lower rates of 30-day and 1-year mortality. Moreover, there is no difference in the magnitude of this association by age, i.e., older patients appear to benefit at least as much as younger patients. Even among subgroups where BB and/or RASi are often withheld in older patients, namely those with hypotension, renal insufficiency and frailty, BB and/or RASi use at discharge is associated with lower 1-year mortality or readmission among those aged 85 and above. These data suggest that discharge on BB, RASi or both is associated with improved outcomes, regardless of age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Beckie Friesenhahn from the American Heart Association for her assistance with this project.

Sources of Funding:

This work is supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) [K23HL142835 to LG]. The funding source (NHLBI) did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Deepak L. Bhatt discloses the following relationships – : Dr. Deepak L. Bhatt discloses the following relationships - Advisory Board: AngioWave, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, High Enroll, Janssen, Level Ex, McKinsey, Medscape Cardiology, Merck, MyoKardia, NirvaMed, Novo Nordisk, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences, Stasys; Board of Directors: AngioWave (stock options), Boston VA Research Institute, Bristol Myers Squibb (stock), DRS.LINQ (stock options), High Enroll (stock), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, TobeSoft; Chair: Inaugural Chair, American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; Consultant: Broadview Ventures; Data Monitoring Committees: Acesion Pharma, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St. Jude Medical, now Abbott), Boston Scientific (Chair, PEITHO trial), Cleveland Clinic (including for the ExCEED trial, funded by Edwards), Contego Medical (Chair, PERFORMANCE 2), Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo; for the ABILITY-DM trial, funded by Concept Medical), Novartis, Population Health Research Institute; Rutgers University (for the NIH-funded MINT Trial); Honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Chair, ACC Accreditation Oversight Committee), Arnold and Porter law firm (work related to Sanofi/Bristol-Myers Squibb clopidogrel litigation), Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; AEGIS-II executive committee funded by CSL Behring), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group (clinical trial steering committees), Cowen and Company, Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees, including for the PRONOUNCE trial, funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals), HMP Global (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), K2P (Co-Chair, interdisciplinary curriculum), Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD (CME steering committees), MJH Life Sciences, Oakstone CME (Course Director, Comprehensive Review of Interventional Cardiology), Piper Sandler, Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee, and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees), Wiley (steering committee); Other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); Patent: Sotagliflozin (named on a patent for sotagliflozin assigned to Brigham and Women’s Hospital who assigned to Lexicon; neither I nor Brigham and Women’s Hospital receive any income from this patent.) Research Funding: Abbott, Acesion Pharma, Afimmune, Aker Biomarine, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Beren, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Eisai, Ethicon, Faraday Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Fractyl, Garmin, HLS Therapeutics, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Janssen, Javelin, Lexicon, Lilly, Medtronic, Merck, Moderna, MyoKardia, NirvaMed, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Owkin, Pfizer, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Recardio, Regeneron, Reid Hoffman Foundation, Roche, Sanofi, Stasys, Synaptic, The Medicines Company, 89Bio; Royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Braunwald’s Heart Disease); Site Co-Investigator: Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, Endotronix, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott), Philips, SpectraWAVE, Svelte, Vascular Solutions; Trustee: American College of Cardiology; Unfunded Research: FlowCo, Takeda.

We offer special and heartfelt posthumous acknowledgement for Dr. Lauren Gilstrap and her leadership of this work. While her time with us was short, we are grateful for the positive impact she had on science, the heart failure community, her friends, family, colleagues, and patients. We present this manuscript as a statement of her dedication to patients and the field of heart failure.

Biography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. The SOLVD Investigattors. N Engl J Med. Sep 03 1992;327(10):685–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. U.S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. N Engl J Med. May 23 1996;334(21):1349–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packer M, Coats AJ, Fowler MB, et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. The New England journal of medicine. May 31 2001;344(22):1651–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Investigators S, Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, Hood WB Jr., Cohn JN. Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med. Sep 3 1992;327(10):685–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deedwania PC, Gottlieb S, Ghali JK, Waagstein F, Wikstrand JC, Group M-HS. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of beta-adrenergic blockade with metoprolol CR/XL in elderly patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J. Aug 2004;25(15):1300–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitzman DW, Rich MW. Age disparities in heart failure research. JAMA. Nov 3 2010;304(17):1950–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heart failure projected to increase dramatically, according to new statistics. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2018/05/01/heart-failure-projected-to-increase-dramatically-according-to-new-statistics#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20people%20diagnosed,in%20new%20window)%20p ublished%20Wednesday.

- 8.Salmon T, Essa H, Tajik B, Isanejad M, Akpan A, Sankaranarayanan R. The Impact of Frailty and Comorbidities on Heart Failure Outcomes. Card Fail Rev. Jan 2022;8:e07. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2021.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erdmann E, Lechat P, Verkenne P, Wiemann H. Results from post-hoc analyses of the CIBIS II trial: effect of bisoprolol in high-risk patient groups with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. Aug 2001;3(4):469–79. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00174-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flather MD, Shibata MC, Coats AJ, et al. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS). Eur Heart J. Feb 2005;26(3):215–25. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammill BG, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC, Schulman KA, Curtis LH. Linking inpatient clinical registry data to Medicare claims data using indirect identifiers. Am Heart J. Jun 2009;157(6):995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banach M, Bhatia V, Feller MA, et al. Relation of baseline systolic blood pressure and long-term outcomes in ambulatory patients with chronic mild to moderate heart failure. Am J Cardiol. Apr 15 2011;107(8):1208–14. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson PN, Rumsfeld JS, Liang L, et al. A validated risk score for in-hospital mortality in patients with heart failure from the American Heart Association get with the guidelines program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. Jan 2010;3(1):25–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.854877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith GL, Lichtman JH, Bracken MB, et al. Renal impairment and outcomes in heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. May 16 2006;47(10):1987–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. May 5 2018;391(10132):1775–1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Mar 2001;56(3):M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Jul 2007;62(7):722–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans SJ, Sayers M, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. The risk of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older patients in relation to a frailty index based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Age Ageing. Jan 2014;43(1):127–32. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. Aug 30 2005;173(5):489–95. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas LE, Li F, Pencina MJ. Overlap Weighting: A Propensity Score Method That Mimics Attributes of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. Jun 16 2020;323(23):2417–2418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li F, Morgan KL, Zaslavsky AM. Balancing Covariates via Propensity Score Weighting. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2018/01/02 2018;113(521):390–400. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2016.1260466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flather MD, Yusuf S, Kober L, et al. Long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left-ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. ACE-Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. Lancet. May 6 2000;355(9215):1575–81. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02212-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilstrap L, Austin AM, Gladders B, et al. The association between neurohormonal therapy and mortality in older adults with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Geriatr Soc. Jun 15 2021;doi: 10.1111/jgs.17310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilstrap L, Austin AM, O’Malley AJ, et al. Association Between Beta-Blockers and Mortality and Readmission in Older Patients with Heart Failure: an Instrumental Variable Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. Aug 2021;36(8):2361–2369. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06901-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilstrap LG, Stevenson LW, Small R, et al. Reasons for Guideline Nonadherence at Heart Failure Discharge. J Am Heart Assoc. Aug 7 2018;7(15):e008789. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.