Abstract

The current paper presents a lifespan model of ethnic-racial identity (ERI) from infancy into adulthood. We conceptualize that ethnic-racial priming during infancy prompts nascent awareness of ethnicity/race that becomes differentiated across childhood and through adulthood. We propose that the components of ERI that have been tested to date fall within five dimensions across the lifespan: ethnic-racial awareness, affiliation, attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge. Further, ERI evolves in a bidirectional process informed by an interplay of influencers (i.e., contextual, individual, and developmental factors, as well as meaning-making and identity-relevant experiences). It is our goal that the lifespan model of ERI will provide important future direction to theory, research, and interventions.

Ethnic-racial identity (ERI) encompasses the process and content that defines an individual’s sense of self related to ethnic heritage and racial background. It includes labels individuals use to define themselves according to ethnicity/race; awareness, beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge they have about their ethnic-racial background; enactment of their identity; and processes by which each of these dimensions evolve (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). ERI is recognized as an important developmental competency (Williams et al., 2012) that can promote positive adjustment in the face of risk or adversity (Neblett et al., 2012). Scholars emphasize that ERI development is dynamic and evolves throughout the lifespan (Syed et al., 2007). However, most conceptual models of ERI have focused independently on distinct developmental periods, such as childhood (e.g., Bernal et al., 1990) or adolescence (see Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014 for review), without an explicit lifespan perspective.

This relatively piecemeal approach makes it difficult to chart continuity across developmental periods when identity components are defined specific to a single developmental period, with little effort tracing either the origin or maturation of components beyond a single developmental period. The resulting scholarship gives the impression of disjointed development of ethnic-racial identity. To piece together disparate scholarship in the field’s conceptual understanding of ERI, Adriana Umaña-Taylor and Esther Calzada assembled a work group funded by the National Science Foundation. The goal of our work group was to develop an integrated model of ERI development that would describe when components of ERI first emerge, how they unfold from one developmental period to another, which components have yet to be studied at particular periods, as well as the factors that influence ERI development within and across developmental periods.

Consistent with our lifespan lens, we use the term ethnic-racial identity to describe the process that begins early in infancy and progresses throughout late adulthood. As discussed below, many ERI components that have been identified as critical during adolescence are rooted in processes that emerge much earlier (Cross & Fhagen-Smith, 1996; Spencer, 1985). As such, we explicitly acknowledge that ERI work occurring early in the lifespan is indeed reflective of developing identity. Likewise, Erikson (1968) argued that identity “begins in the initial meeting of infant and mother” and although it has “its normative crisis in adolescence,” it neither begins nor ends inside this developmental window (pp. 22, 23). Thus, we push back on the recommendation to refer to pre-adolescent processes as ethnic-racial identification (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014) because such labeling contributes to the privileging of adolescence in identity scholarship. Indeed, we hope that through the lifespan model, we can broaden the view of ERI as a continuously evolving process that occurs across development.

ERI research has had a long, rich, and sometimes divided history. Erik Erikson’s developmental notions about identity development have been applied widely in ethnic identity models (e.g., Phinney, 1992). At the same time, however, scholars who attempted to incorporate developmental components into conversion racial identity models (e.g., Cross, 1971) were often met with harsh critique (Rogers et al., in press). We shed light on these tensions of the past to acknowledge how this early contention brought on by developmental psychologists may have created divisiveness and hampered progress. A primary motivation of our lifespan model is to bridge past divisions by explicitly building on the work of ERI scholars across fields within psychology (e.g., social, counseling, health, clinical, community) and outside of psychology (e.g., education, social work, ethnic studies). By adding an intentional developmental lens to ERI, we aim to unite and enhance, rather than contrast or oppose, existing models across fields that have harvested a solid foundation upon which we can continue to build.

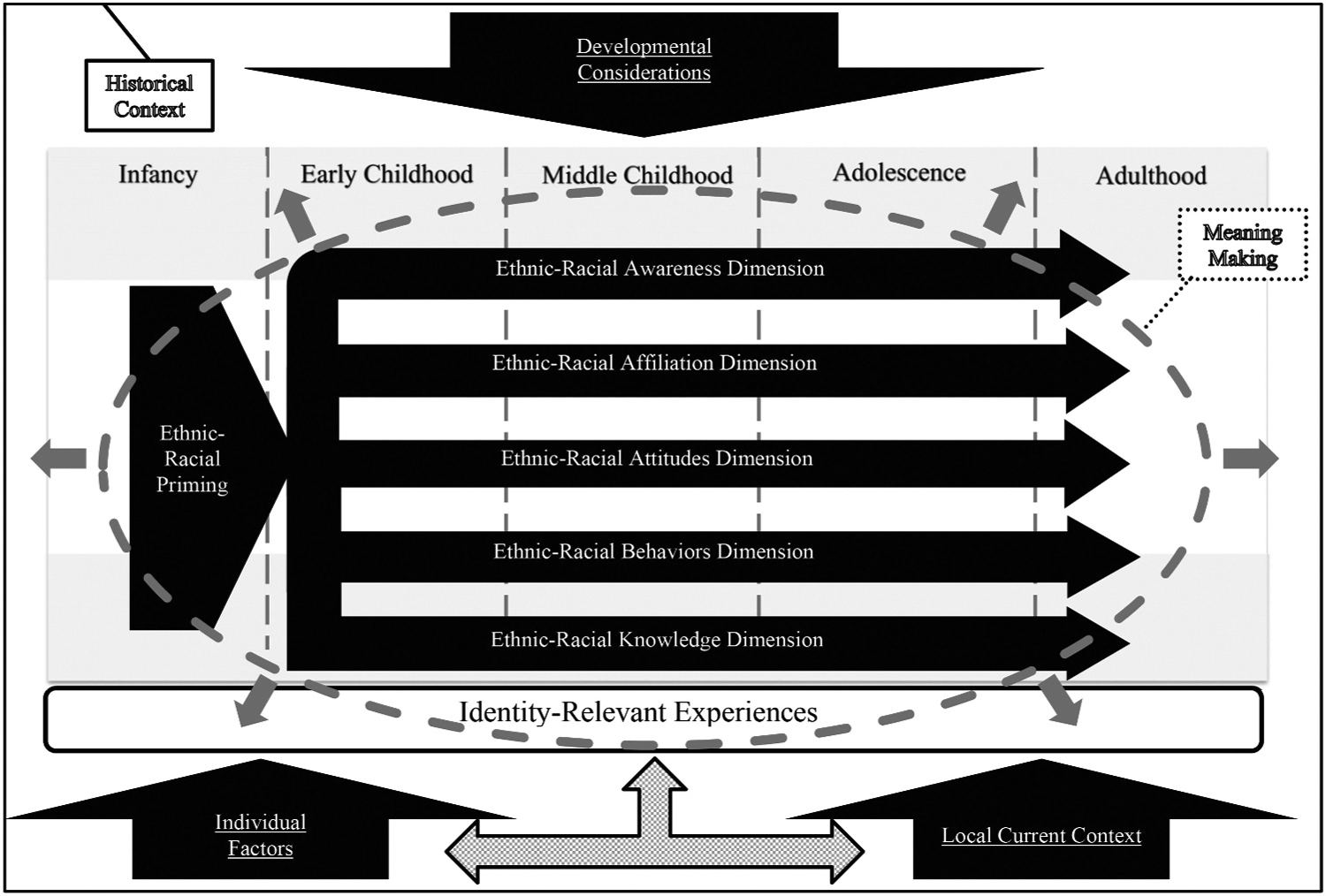

Most recently, we build on the work done by the Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Umaña-Taylor et al. (2014) synthesized theories of ethnic identity and racial identity to outline the key process and content dimensions of ERI in adolescence and young adulthood. Further, they specified critical social environmental contexts (e.g., family, peers) that inform ERI during these two important developmental periods. We extend this work by identifying potential influencers of change in ERI throughout the lifespan, with careful attention to proximal and distal contexts that inform development and the interaction of these contexts with the growing conceptual and social cognitive abilities. We start with infancy to present a lifespan model of ERI that bridges the work that has been siloed within developmental periods (e.g., early childhood or adolescence) to draw connections across periods (e.g., how components of ERI change and build on each other from one developmental period to the next). Our lifespan model integrates work into five key ERI dimensions that extend across developmental periods (see Figure 1). The model also outlines the key influencers of ERI and provides empirical support at each developmental period and across specific developmental periods.

FIGURE 1.

The lifespan model of ethnic-racial identity.

Although we present a lifespan model that we hope will stimulate longitudinal collaborations, the ERI components and influencers that we outline at each developmental period will also be useful for scholars studying ERI within specific developmental periods (e.g., in cross-sectional studies). Our approach provides a bird’s eye view of gaps within the literature for any given developmental period and identifies important areas for future research. We begin with a brief introduction to terminology and factors proposed in our model.

OVERVIEW OF THE MODEL

Our lifespan model of ERI is grounded in cultural ecological frameworks (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1979; García Coll et al., 1996; Spencer, 2006; Vélez-Agosto et al., 2017), with special attention to the individual, contextual, and developmental factors that inform identity-relevant experiences and meaning-making associated with ERI development across the lifespan (see Figure 1), which we refer to broadly as influencers. The main premise of our model is that ERI starts in infancy with ethnic-racial priming that prompts nascent awareness of ethnicity/race. We propose that, across development, ERI manifests in both implicit and explicit forms within five dimensions: ethnic-racial awareness, ethnic-racial affiliation, ethnic-racial attitudes, ethnic-racial behaviors, and ethnic-racial knowledge. In our synthesis of the literature, we found that although these five core dimensions were labeled differently at different developmental periods, each seems to represent common underlying ERI dimensions. Importantly, our purpose of devising broad ERI dimensions is to allow the threading together of existing components that have been studied in distinct developmental periods to better understand their connections over time, identify areas of missing knowledge, and provide a foundation upon which future work can build. We start by providing our definitions of these dimensions used in this paper.

ERI Dimensions

Ethnic-racial awareness captures individuals’ perceptions that ethnic-racial groups are categories with social meaningfulness, as well as individuals’ perceptions of how ethnic-racial groups are viewed in society. Ethnic-racial affiliation reflects individuals’ sense of membership in or belongingness to one or more ethnic-racial groups. Ethnic-racial attitudes refer to how individuals evaluate their ethnic-racial group(s) and their membership within their ethnic-racial group(s). Ethnic-racial behaviors include individuals’ behavioral enactments (sometimes referred to as performances or role behaviors) of cultural values, styles, language use customs, and/or processes (e.g., exploring and resolving) involved in trying to gain a sense of one’s ethnic-racial groups(s). Finally, ethnic-racial knowledge captures individuals’ working understanding of the behaviors, characteristics, values, and customs that are relevant to one’s ethnic-racial group(s).

We posit that these five dimensions of ERI are evident (albeit in different ways and at different magnitudes) throughout the lifespan. Across developmental periods, the ERI dimensions manifest as functions of a complex interplay of contextual, individual, and developmental factors – i.e., the components of ERI. A component can be thought of as a snapshot in time of that ERI dimension. For example, as described below, ethnic-racial awareness (a dimension) manifests as ethnic-racial sorting in early childhood, but evolves into public regard in adolescence. However, the field has yet to draw explicit connections between components (e.g., ethnic-racial sorting, public regard) across developmental periods. Our lifespan model has this as a primary goal.

Additionally, we conceive that although ERI components evolve developmentally into each other over time, the process does not necessarily occur linearly and ERI is not always positive or central to an individual. For example, although childhood ethnic-racial sorting is proposed to evolve into public regard in adolescence, children who can sort early may experience high public regard (i.e., positive perceptions about how others view their ethnic-racial group) in early adolescence, then a period of low public regard in mid adolescence, followed by another period of high public regard in emerging adulthood. Indeed, scholars have noted that individuals may cycle through points in which they question their identity and revisit earlier socialization experiences, and that through these processes they are able to experience conversions to different identity stages (Cross & Vandiver, 2001; Parham, 1989). In line with these notions, we conceive that the potentially cyclical changes in components across development is informed by the interplay of influencers, which we outline below.

Interplay of Influencers

ERI dimensions (and components within them) unfold as a function of identity-relevant experiences, which are experiences that cause an individual to consider and evaluate their ERI. Ethnic-racial socialization and discrimination are examples of important identity-relevant experiences, which themselves emerge at the interface of contextual and individual factors. First, as illustrated at the top of Figure 1, developmental considerations shape individuals’ meaning-making of these identity-relevant experiences; put differently, ERI meaning is made according to individuals’ unique developmental (e.g., perceptual and cognitive) capacities, or how they filter or interpret identity-relevant experiences. In transitions from infancy to childhood to adolescence to adulthood, developmental capacities expand, which allows individuals to use more complex processes in making meaning of their identity-relevant experiences (see Spencer, 2006 for more discussion about meaning-making, and below for an example of meaning-making alongside the other influencers in the lifespan model of ERI). Although cognitive capacities may impose constraints on what meaning can be made, we also propose that as individuals’ developmental capacities mature, they may revisit identity-relevant experiences and dimensions formed during earlier developmental periods. Individuals can then engage in more complex forms of meaning-making and subsequent adjustment in their ERI components. This adjustment may be linear or non-linear and cyclical. For example, the meaning-making process may result in formerly negative ERI attitudes changing to positive, which may then cycle back to negative with the experience of identity-relevant experiences (e.g., discrimination).

Second, as illustrated at the bottom of Figure 1, there is a complex interplay of ecological factors with individual factors that create identity-relevant experiences and the meaning given to them, depending on the local current context. We refer specifically to the role of the local current context to acknowledge experiences in settings such as the family, neighborhood, and schooling, and to distinguish these contextual realities from the broader historical context in which individuals and local current contexts are embedded. The local current context interacts with individual factors, namely individuals’ social addresses based on social class, gender, ethnicity/race, and the sociological meanings attached to individual phenotypic features (e.g., skin tone, hair texture; García Coll et al., 1996; Spencer, 2017). These individual factors to which society attaches social meaning elicit socializing scripts that are specific to the child. The scripts elicited may be different within the family compared to socializing scripts elicited outside the family (e.g., teachers, police, social workers).

Across the lifespan, developmental and ecological constraints may be imposed, but as the capacities and ecological contexts continue to expand, more complex forms of meaning can be made out of identity-relevant experiences. Some children may function in contexts in which ethnicity/race are primed more often or viewed as more salient. Consequently, children who are exposed to many identity-relevant experiences may enact, develop, and manifest ERI components in a manner that seems to exceed their age-graded cognitive capabilities in any given ERI dimension. For example, consider an African American pre-kindergarten child raised in a predominantly White town in the U.S. (local current context) at a time that the historical context involves increased explicit White nationalism messages (Shaohua, 2017). The child may have many identity-relevant experiences during this developmental period (e.g., discrimination from peers, and/or buffering ethnic-racial socialization messages from parents) that prompt meaning-making processes associated with being African American and stimulate ERI processes. These early experiences may provide emergent notions about their ethnic/racial status that they will build upon into subsequent developmental periods. Conversely, consider children in contexts in which identity-relevant experiences are less salient. They may exhibit cognitive capacity but the formation of ERI components may be delayed relative to other children for whom their ethnic-racial status is socially salient, simply because of limited affordances due to lack of contextual exposure to ethnic-racial issues. For example, consider a White adolescent raised in a predominately White town for whom ethnic-racial status is less salient than social class. This particular youth has the cognitive resources to process experiences in complex ways but may not psychologically or socially engage in ERI processes until later. Consider the same person later as an adult who is relocating for employment in a setting with greater ethnic-racial diversity of coworkers (local current context), and where conversations about ethnicity and race are prominent (identity-relevant experiences). The adult may now engage in forming various components of ERI but may also reflect back on their meaning-making in childhood and the types of or paucity of identity-relevant experiences that shaped development to that point.

Third, as illustrated by the box that bounds Figure 1, the historical context defines a reality that permeates our model: all ERI dimensions across developmental periods, individual factors, the local current context, identity-relevant experiences, meaning-making, and developmental considerations. Each of these is shaped by the historical context, and in turn shapes the historical context, over time.

Fourth, within the proposed model, the arrows emanating from the meaning-making sphere represent the notion that ERI development is considered a bidirectional process. We recognize that not only do various factors influence ERI, but ERI mutually influences those factors over time. For example, contextual factors and identity-relevant experiences inform the development of ERI, and ERI development informs subsequent contexts (e.g., selection of friends and neighborhood) and identity-relevant experiences (e.g., perceived discrimination).

In short, we argue that a lifespan approach to understanding ERI explicitly addresses the emergence and evolving forms of ERI development that are often missed with period-specific approaches (Baltes et al., 2006). To further illustrate the primary concepts of a lifespan approach, we begin with infancy and a discussion of ERI in terms of ethnic-racial priming. We then discuss subsequent aspects of the model by (a) providing an overview of the interplay of influencers proposed in the lifespan model that are most relevant at each developmental period, and (b) reviewing examples of the five ERI dimensions and influencers that have been tested in existing work throughout each developmental period. We highlight influencers, gaps, and threads across developmental periods. We end with an integrative discussion that highlights key recommendations for future scholarship.

INFANCY AND ETHNIC-RACIAL PRIMING

The origins of children’s ERI, which we refer to as ethnic-racial priming, can be traced to development during the first year of life. Research suggests that this early development is not based on any inherent ethnocentrism or racial animus. Rather, infants appear to be born with the potential to be receptive to socialization across myriad contexts. Between three and nine months, however, infants demonstrate perceptual narrowing (Scott et al., 2007) whereby their social perceptions become more narrowly focused onto familiar social, cultural, and ethnic-racial stimuli.

Regarding ethnicity/race specifically, from three to six months infants show preferences for ethnic-racial groups to which they have been most exposed, which often mirror the infants’ own ethnicity/race (Anzures et al., 2013). By nine months, infants are less able to recognize faces from unfamiliar ethnic-racial groups, compared to faces from familiar ethnic-racial groups, and this same-race recognition has been replicated for Asian American, Black, White, and Latinx infants (for a review see Timeo et al., 2017). The consistency of contextually-determined preference across infants from diverse backgrounds despite different phenotypical appearances suggests that infants’ preferences are not due to any intrinsic bias against any phenotype (e.g., lighter skin complexion), but are influenced by infants’ exposure to specific individuals in their local current context.

The perceptual narrowing with respect to infants’ reactions to faces from unfamiliar races has been connected to a perceptual bias that was first identified in adulthood, coined the Other Race Effect (ORE; Feingold, 1914). Like infants, adults manifesting ORE recognize same-race faces more easily than other-unfamiliar-race faces, and the ORE in adulthood is associated with myriad forms of cognitive bias that favor ingroup members, including increased amygdala activity, suggesting startle or fear reactions when ORE is evoked. Telzer et al. (2013) found that amygdala activity in adulthood in response to faces of other races was predicted by the degree of ethnic/racial segregation the adults had during infancy.

It appears that infant reactions to ethnic-racial status are not based on either intrinsic ingroup allegiance or outgroup derogation but may serve to assist in the formation of attachment during infancy by differentiating caretakers from strangers. Interestingly, findings have also indicated that ORE can be weakened when infants are exposed to outgroup members, which is believed to provide them with awareness of individualizing characteristics that enable infants to think about each outgroup member as an individual (for review see Timeo et al., 2017). That is, ORE in infants could be attenuated by pairing the other race faces with individual names or references.

Other areas of research also suggest that positive associations with one’s own race have a basis in infancy. For example, infants show visual preference with same-race faces when paired with “happy” music combinations and other-race preference when paired with “sad” music combinations (Xiao et al., 2018); show preferences for same-race individuals when resources are being distributed unequally (Burns & Sommerville, 2014); and learn behaviors more readily from same-race, compared to other-race, models (Pickron et al., 2017). We would argue that these preferences, just like ORE, emerge from infants’ contexts as a form of ethnic-racial priming. Furthermore, we consider ethnic-racial priming to be an important foundation for implicit ERI perceptions and explicit ERI cognitions in later developmental periods.

INTERPLAY OF INFLUENCERS ACROSS DEVELOPMENTAL PERIODS

Early Childhood

Building on ethnic-racial priming in infancy, developmental considerations in early childhood involve shifts in children’s cognitive abilities allowing them to think more explicitly, albeit concretely, about ethnicity/race. Early childhood marks the preoperational stage of cognitive development, which is characterized by children’s ability to engage in symbolic thought or to use words and pictures to represent objects (Piaget, 1970). Accordingly, theories on children’s ERI mainly focus on their explicit, verbalized understandings of ethnicity/race, and are primarily concerned with how children integrate their initial theories and attitudes about ethnicity/race with observable differences (e.g., skin, hair, and eye color; Quintana, 1998). However, children’s implicit notions about ethnicity/race may be more complex than what can be verbalized or explicitly measured, with evidence demonstrating that children have an implicit sense of ethnicity/race prior to their ability to verbalize their understanding (Hirschfeld, 1995).

As outlined in the lifespan model of ERI, children’s identity-relevant experiences and individual factors help influence their ERI, whether explicit or implicit. An example of such an influencer is ethnic-racial socialization, which captures the interactive processes in which others (e.g., family) and the child learn about their culture and prepare for racialized experiences (Hughes et al., 2006). For example, and consistent with the lifespan model, the effect of parents’ socialization messages on ERI varies by children’s individual characteristics of gender and skin tone (Derlan et al., 2017). The lifespan model also posits that experiences further vary by children’s contexts and their meaning-making processes during this period.

Middle Childhood

During middle childhood, developmental considerations include children transitioning to the more logical, systematic thinking of the concrete operational stage (Piaget, 1970). Quintana (1998) (see also Bernal et al., 1990) suggests that during this period, children move to a literal understanding of ethnicity/race where they think more about their labels, have more complex knowledge and preferences, engage in more behaviors, and understand the relevance of behaviors for ERI.

Contextual factors continue to influence ERI in middle childhood. For example, two aspects of the local current context, peers and the school community, begin to play a larger role. For example, same-race friends have been found to be influential to ERI development during this period (Jugert et al., 2020). Furthermore, by 8 years of age, children watch an average of two hours of television a day (Chassiakos et al., 2016). Therefore, in middle childhood, children have greater exposure to the role of ethnicity/race in social life, and are more likely to have aversive identity-relevant experiences (e.g., discrimination, stereotyping expressed by others about one’s ethnic-racial group) from which they use their increasingly complex social cognition to make meaning.

Adolescence

Adolescence continues many of the considerations seen in infancy and childhood. At the same time, regarding developmental considerations, adolescence presents new affordances and challenges. Around 11–12 years, adolescents enter the formal operational stage of cognitive development, which includes abstract thinking, deductive reasoning, and hypothetical thinking (Piaget, 1970), which is theorized to advance their understanding of ethnicity/race. In Quintana’s (1998) model, the transition to adolescence corresponds to a shift in ERI based on social perspectives of ethnicity/race (i.e., Level 2), in which ERI understanding reflects awareness of social consequences of ethnicity/race (e.g., possibility of discrimination or bias). Adolescents demonstrate that they are able to construct ERI based on integrations of identity-relevant experiences across situations and contexts, and assume a greater group consciousness (Level 3; Quintana, 1998). Accordingly, adolescents may seek to identify with, be loyal to, and hold common values, attitudes, and beliefs with their ingroup members. Despite the developmental shifts from childhood to adolescence, scholars have not sufficiently examined the complexities of meaning-making between these development periods. Although assumed to have an “adult-like” understanding of ethnicity/race during late childhood, adolescents continue to develop their understanding into adulthood, which needs further exploration (Rogers et al., in press).

The two influencers that have received the most attention in adolescence are context and identity-relevant experiences. For example, discrimination (an identity-relevant experience) has been associated with various ERI components (e.g., Pahl & Way, 2006; Seaton et al., 2009). The school context is often a focus, especially the transition to middle and high school, given that youth are exposed to peers that provide opportunities for ERI development via other-race friendships (e.g., Kiang et al., 2010) and same-race friendships (Derlan & Umaña-Taylor, 2015).

Adulthood

Adulthood is characterized by entry into new roles and environments. In Quintana’s (1998) model, adults have reached Level 4, which involves a more integrated ethnic-racial group consciousness that reflects complex understandings of intragroup and intergroup dynamics. For example, adults may consider the intersectionality of their social identities (Crenshaw, 1989) in terms of how their collective lived experiences are comprised of ethnicity/race and other identities (e.g., gender, sexual orientation). Additionally, in many Western industrialized nations, adults are delaying traditional milestones of adulthood, such as marrying and having children, and spending more time exploring their identities (Arnett, 2000). A particularly important contextual influencer of ERI for many individuals is the transition to college, and much of the ERI research on adulthood has centered on college students. Like the transition to middle and high school, this transition can bring increased contextual changes and identity-relevant experiences, such as exposure to more diverse peers, experiences with discrimination, and opportunities to become involved in diverse extracurricular activities.

Although less work has focused beyond emerging adulthood, we argue that ERI processes continue to unfold throughout the lifespan as identity-relevant experiences trigger new forms of meaning-making or identity reconstruction (e.g., Cross, 1995). Scholars have identified contextual influencers and identity-relevant experiences that might promote identity status change in adulthood, including age-graded events (e.g., leaving high school), history-graded events (e.g., September 11 attacks, double coronavirus and racism pandemics), critical life events (e.g., job loss), and family life cycle changes (e.g., marriage), to name a few (Kroger & Green, 1996). For example, becoming a parent and/or grandparent may motivate adults to think about their ERI in different ways as they consider how they will socialize children/grandchildren; furthermore, interactions with children can cause changes in parents’ and grandparents’ ERI. Work in this area has predominantly focused on Black and Latinx mothers, but findings suggest differences in how mothers socialize their children based on their own ERI and individual factors of their children (e.g., Derlan et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2017).

ERI COMPONENTS WITHIN FIVE DIMENSIONS AND EXAMPLES OF INFLUENCERS

In this section we describe how each ERI dimension changes throughout the lifespan, and provide examples of the role of influencers. We piece together the components that have been studied to date within each ERI dimension, identify gaps in current literature, and highlight important future directions.

The ERI Dimension of Awareness

Ethnic-racial awareness captures individuals’ perceptions that ethnic-racial groups are categories with social meaningfulness, as well as individuals’ perceptions of how ethnic-racial groups are viewed in society.

Early Childhood

We propose that ethnic-racial priming in infancy demonstrates infants’ implicit sorting abilities, which later supports their awareness. We know that by age 5–6 years, about half of children are able to use ethnicity/race to correctly categorize individuals and can explain their sorting (Pauker et al., 2017). This corresponds to children’s shift from being aware of ethnic-racial differences to assigning meaning (i.e., category labels) to those differences.

Further, we propose that this sorting ability captures children’s implicit understanding of ethnicity and race and reflects the initial seeds of ethnic-racial salience (the extent to which ethnicity/race are relevant to self-concept in a particular situation; Sellers et al., 1998) and ethnic-racial public regard (individuals’ perceptions about how others view their ethnic-racial group; Sellers et al., 1998). Awareness in general, and salience in particular, is important to understand throughout the lifespan because it is the way in which ethnicity/race as a category comes to have meaning for identity (Yip et al., 2019). In other words, salience allows current and past events to be viewed through the lens of one’s ethnic-racial group membership, prompting attempts to integrate their membership into their beliefs and attitudes. Correctly assigning category labels is the first explicit acknowledgment of the meaningfulness of ethnicity/race.

Middle Childhood

By middle childhood, a high percentage of Black and White children can consistently categorize Black and White individuals by race (Pauker et al., 2017). However, sorting performance is less consistent for children of other ethnic-racial groups and when other groups, including multiracial individuals, are included (e.g., Liu & Blila, 1995). For example, when Black, Latinx, White, Asian, and American Indian children aged 7 to 10 were asked to label dolls or pictures from the same ethnic-racial groups, only 35% could correctly do so. Thus, although it is assumed that awareness is fully developed by middle childhood, empirical evidence does not support this conclusion across ethnic-racial backgrounds. It may be that children are aware of ethnicity/race as categories and can identify major phenotypical distinctions (i.e., skin color differences between Black and White individuals). However, they may not yet be attuned to more subtle phenotypical and social distinctions between multiple groups. The lack of awareness for ethnicity/race is in contrast to another social identity, gender, where categorization and salience is fully established before middle childhood (Bigler & Liben, 2007).

We propose that these early understandings of group distinctions may be precursors to ethnic-racial salience and public regard. There is some evidence that ethnicity/race is salient in fourth grade (Brown et al., 2011) and that contextual cues can prime salience in middle childhood, at least in biracial children (Gaither et al., 2014), but no studies connect salience or public regard to sorting ability. It is possible that the children who perform best on sorting tasks are those for whom ethnicity/race is most salient.

Adolescence

By adolescence, salience and public regard, consistent with our model, vary by individual factors, contextual factors and identity-relevant experiences. For example, public regard tends to be stable in middle school (Hughes et al., 2011) and decrease in later adolescence (Altschul et al., 2006; Seaton et al., 2009). However, in one study public regard was stable for middle schoolers in a Midwestern school but declined significantly among youth in the Southwest (Santos et al., 2017). Decreases in public regard are likely due to youths’ experiences with discrimination, which has been found to increase in adolescence (Seaton et al., 2009), as well as their increasing awareness of societal stereotypes (Way et al., 2013). Experiences with discrimination and stereotypes are considered identity-relevant experiences.

In adolescence, public regard and salience interact with each other and other components of ERI. For example, variability in salience across contexts may prompt youth to consider the meaning of their ethnic-racial group membership across those various contexts (Yip et al., 2019). In support of this, one study showed that daily salience was associated with greater exploration six months later, especially for those with the most variability in salience (Wang et al., 2017).

Adulthood

In adulthood, salience and public regard continue to be impacted by influencers and to interact with other components of ERI. For example, as in adolescence, experiences with discrimination are associated with lower public regard (e.g., Sellers et al., 2003). However, as adults continue to accumulate experiences with others over time and integrate their understanding of ethnicity/race with what they see in the media and everyday life, the importance of public regard may increase. Additionally, adults must often navigate diverse situations on a daily basis (e.g., work, home) that shape their moment-to-moment experiences of ERI and overall outcomes (Yip et al., 2019).

Summary of ERI Awareness across Development and Future Directions

Young children’s exposure to individuals of the same and different ethnic-racial backgrounds informs their ability to give initial meaning to ethnic-racial categories. Children’s sorting ability in early and middle childhood are evidence of their growing awareness of the complexity of ethnicity/race and are the foundation for perceptions of salience and public regard in adolescence and adulthood. Salience and public regard are dependent on influencers like discrimination.

Future work is needed in several areas: first, research should connect awareness across developmental periods, particularly in showing whether exposure to more diverse individuals in infancy is linked to more accurate sorting and to demonstrate how sorting in childhood connects to salience and public regard in adolescence. Additionally, an examination of how influencers play a role in shaping ERI awareness components is needed. It is also unclear how early salience and public regard can be reliably measured. Research is needed on the bidirectional relations between public regard and related identity-relevant experiences (e.g., discrimination, coping with bias, racial rejection sensitivity).

Finally, ERI salience has received less attention across the lifespan but especially in adulthood. Notably, given that salience reflects a momentary or situational awareness, and that ERI research to date has been limited in its recognition and assessment of fluidity of ERI (Rogers et al., in press), opportunities abound to gain more insight and understanding of this key dimension of ERI.

The ERI Dimension of Affiliation

Ethnic-racial affiliation reflects individuals’ sense of membership in or belongingness to one or more ethnic-racial groups.

Early Childhood

We posit that affiliation in early childhood includes self-labeling and constancy. Children begin to implicitly understand their group membership in infancy and more explicitly in early childhood as they learn to self-label. Early scholars posited that children could self-label their ethnicity/race by 7 years (Aboud, 1988), and other studies supported this timeline (e.g., Bernal et al., 1990; Liu & Blila, 1995). However, recent research suggests that self-labeling emerges even earlier. For example, in two recent studies, the majority of Mexican and Dominican American preschool and kindergarten children (Serrano-Villar & Calzada, 2016) and the majority of Mexican-origin 5-year-old children correctly self-labeled (Derlan et al., 2017). According to our lifespan model of ERI, the discrepancies in findings may be due to the changes in influencers, such as the historical context (e.g., change in ethnic-racial demographics), local current context (e.g., more diverse schools), or identity-relevant experiences (e.g., socialization occurring earlier), which prompt children to think about their ethnicity/race earlier.

Another aspect of ERI affiliation that has been included in existing theory and tested empirically is constancy (i.e., understanding that ethnicity/race does not change; Bernal et al., 1990); however, this construct warrants further careful future investigation. Scholars posited previously that all children would demonstrate constancy by 8 years (Aboud, 1988), but it seems that in early childhood, few children have constancy, although it increases toward the end of this period for some (e.g., Lam & Leman, 2009; Pauker et al., 2010). For example, in one study only about half (i.e., 57%) of Mexican and Dominican American preschool and kindergarten children demonstrated ethnic-racial constancy (Serrano-Villar & Calzada, 2016).

Middle Childhood

The majority of children in middle childhood are able to accurately self-label (Akiba et al., 2004; Rogers & Meltzoff, 2017; Rogers et al., 2012). In terms of ethnic-racial constancy, most researchers assume that constancy is fully established in this period, but there are no studies in which more than 85% of children under age 11 demonstrate constancy (e.g., Bernal et al., 1990; Lam & Leman, 2009; Semaj, 1980; Serrano-Villar & Calzada, 2016). It is likely that children’s negotiation of labels and constancy is directly related to their attitudes in this period and later during adolescence.

Adolescence

Research on children’s self-labeling focuses on being able to correctly self-label; however, we propose that with increased cognitive and meaning-making abilities, adolescents negotiate multiple influences in their choice of and changes in self-labeling. Aligned with the lifespan model of ERI, individual factors, such as group norms, surname, skin tone, facility with the group’s language, and immigration status influence self-labeling (Herman, 2004; Kiang & Luu, 2013; Renn, 2008). For example, multiracial individuals with darker skin tones are more likely to self-label as a minority (Rockquemore & Brunsma, 2002), and second-generation immigrant youth are more likely to use a pan-ethnic or hyphenated American label (e.g., “Mexican-American”) compared to first-generation youth (Fuligni et al., 2008).

As noted, although constancy is assumed to be established by adolescence, only one study to our knowledge (i.e., Semaj, 1980) examined children above age 10, and the findings showed that just 60% of the oldest age group (10 to 11 years) achieved full understanding of ethnic-racial constancy.

Adulthood

Similar to adolescence, constancy has not been a traditional area of focus in research with adults. Choice of labels in adulthood is similar to the decisions made in adolescence. We posit that important shifts in ERI self-labeling during adulthood may occur in response to individual factors and shifts in local current contexts (e.g., family). For example, adults are negotiating other intersectional identities as cognitive sophistication and, perhaps, the ability to consider the interaction among multiple forms of social identity, peaks. Regarding the local current context, becoming involved in interracial relationships and/or parenting multiracial children are likely to prompt shifts in ERI processes. Adults have to contend with what it means to be a multiracial couple/family and/or how to socialize their children for experiences they themselves might not have encountered (e.g., Franco & McElroy-Heltzel, 2019). Furthermore, adults also must deal with societal changes in the use of certain labels. For example, self-labeling can become more politicized in nature, as seen in the creation of a panethnic “Asian” label after 1965 (Espiritu, 1992), the increase in using “African American” in the 1990s (Smith, 1992), and “Latinx” more recently (Salinas & Lozano, 2017).

Summary of ERI Affiliation across Development and Future Directions

Early sorting ability supports children’s ability to self-label. In applying the lifespan model to understand affiliation over time, little is known about when children transition from knowing ethnic-racial labels ascribed to them to intentionally selecting specific labels to define themselves. For example, a Latinx toddler may be unaware of ethnic-racial labels used by parents. By early and middle childhood, the child may self-label based on the ethnic-racial labels assigned to them in their social context. During adolescence, this youth may intentionally choose different labels that are more personally meaningful (e.g., Latinx, Mexican, Mexican-American, Chicano/a). Thus, the lifespan model highlights that youth transition from not knowing self-labels ascribed to them, to accepting the socially-ascribed label(s), and then to choosing label(s) that are personally meaningful. This critical transition from awareness of, identification with, and formulating meaningful ethnic-racial labels requires more longitudinal examination across developmental periods. It is also important to consider that the use of labels as a marker of ERI affiliation might reflect an inherently fluid or situational process, which could presumably become more complex, but practiced, with development (Kiang & Johnson, 2013). Research is needed that tests these nuances, as well as how influencers impact self-labeling.

Further work is also needed to understand the meaning of constancy across developmental periods, to confirm when and how it is established, and the implications of constancy for other areas of ERI. For example, constancy might predict consistency in self-labeling, and multiracial or immigrant youth might struggle more with constancy compared to monoracial and non-immigrant youth, but to date these questions remain untested. Scholars have shown that ERI may be more fluid (Yip, 2005), especially among multiracial individuals (Gaither et al., 2013), making the construct of constancy itself questionable and in need of further testing.

Finally, an unexplored aspect of the work on ERI affiliation in adolescence and adulthood is a sense of belonging to one’s ethnic-racial group (Derlan & Umaña-Taylor, 2015; Pahl & Way, 2006), which, for some scholars, overlaps with a positive attachment to one’s group (e.g., Phinney, 1992). We conceptualize positive feelings as part of the attitudes dimension, whereas belonging as an aspect of affiliation represents how much one feels a sense of membership within a group. Scholars have noted that ERI literature has been developed in the absence of consideration of sense of belonging to one’s ethnic-racial group (Hunter et al., 2019) and that belongingness is an important component of ERI (Neville et al., 2014). As a context-dependent construct, sense of belonging has been tested consistently in relation to sense of belonging to school (Hussain et al., 2018; Sánchez et al., 2005), but less so in terms of sense of belonging to one’s ethnic-racial group. One way scholars have conceptualized membership is ethnic-racial typicality, which is one’s goodness of fit with the group (Mitchell et al., 2018). Very few studies have examined typicality or how sense of belonging to one’s ethnic-racial group is related to and distinct from other components of ERI affiliation (e.g., self-labeling and constancy). Future work is also needed on how sense of belonging in childhood evolves and changes through adolescence and adulthood, and the interplay of influencers that shape its development over time.

The ERI Dimension of Attitudes

Ethnic-racial attitudes refer to how individuals evaluate their ethnic-racial group(s) and their membership within their ethnic-racial group(s).

Early Childhood

Two components of ERI attitudes in early childhood are ethnic-racial affect (i.e., the positive or negative feelings children have toward their group; formerly termed “ethnic preferences”; Bernal et al., 1990) and ethnic-racial centrality (i.e., how much one’s ethnic-racial group membership is key to one’s self-concept; Sellers et al., 1998). Although theoretical work on social group attitudes in general (e.g., Tajfel & Turner, 1986) and ethnic-racial group attitudes in particular (e.g., Bernal et al., 1990) are more recent, the measurement of ERI attitudes dates back to the seminal doll studies conducted by Clark and Clark (1939). Across decades, subsequent studies implemented the doll study methodology and adapted measures to assess children’s affect toward their own ethnic-racial group, finding that children across ethnic-racial groups tend to have positive attitudes toward their group, for the most part (for a review see Byrd, 2012).

The limited research examining ethnic-racial centrality during early childhood has yielded mixed findings, with different methodologies being used across studies and time. For example, an early study found that children described themselves using external characteristics (e.g., appearance, possessions, behavior; Aboud & Skerry, 1983) instead of social identities. Only two more recent studies have tested centrality in early childhood. One study on early childhood and middle childhood (5 to 12 years) found that the majority of children rated categories other than ethnicity/race as more central (e.g., like pets/animals; Turner & Brown, 2007). However, more recent research focused on social identities (e.g., gender, ethnicity/race) found that 5-year-old Mexican children demonstrated higher levels of ethnic-racial centrality than what had emerged in prior research (Derlan et al., 2017). We propose that this component of ERI may emerge earlier among younger children in the current historical context relative to research conducted more than a decade ago.

Middle Childhood

Research on ERI attitudes during middle childhood has used a variety of measures, including the upward extension of doll study and picture task methodologies from early childhood and downward extensions of adolescent survey measures. For example, Corenblum (2014) found that positive implicit and explicit attitudes among Native Canadian children increased from 2nd through 5th grade. Additionally, increases in positive attitudes were predicted by the emergence of concrete operational thought (i.e., a developmental influencer). Similarly, using adapted adolescent attitude measures, research shows that children, and especially children of color, tend to have high private regard/affirmation in middle childhood (e.g., Witherspoon et al., 2016).

Regarding ethnic-racial centrality, studies have been limited and mixed in their findings. For example, Cavanaugh et al. (2018) found high centrality in a predominantly Mexican sample of middle schoolers. On the other hand, Rogers and Meltzoff (2017) found that in describing their social identities, children 7 to 12 years prioritized other identities (e.g., being a son or student) above their ethnicity/race, suggesting lower ethnic-racial centrality. It could be that disparate findings have emerged because influencers (e.g., local current context or identity-relevant experiences) and/or previous ethnic-racial centrality in early childhood were not considered.

Adolescence

Attitudes are frequently studied in adolescence. Most studies show little change in affect (more commonly termed private regard or affirmation; Sellers et al., 1998; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004, respectively) over the course of adolescence (e.g., Hughes et al., 2011; Kiang et al., 2013; Pahl & Way, 2006; Seaton et al., 2009). However, some studies do show increases (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2015), especially across school transitions (Altschul et al., 2006; French et al., 2006). Consistent with the lifespan model, we propose that influencers, such as the supportiveness of the local school setting (e.g., Altschul et al., 2006), shape changes in affect.

Centrality appears to be stable in mid- to late adolescence (Hoffman et al., 2017; Kiang et al., 2013). However, some work suggests it varies by individual factors, such as ethnicity/race and gender. For example, centrality increased among Black adolescent boys over the first two years of high school (Rogers et al., 2015).

Adulthood

Attitudes are also frequently studied in adulthood, although most studies focus on college students and the college experience as a transition period for changes in ERI (e.g., Syed et al., 2007). Many studies that sample participants outside of a college setting represent a wide age-range with little consideration of age-related differences (e.g., Chae et al., 2017; Cobb et al., 2019). When age differences were considered, ERI attitudes appeared to be relatively stable in mid- and later life (Hoffman et al., 2017). However, like adolescents, middle-age adults attempt to make meaning of ERI in relation to numerous influencers, such as transitions in work or moving to a new neighborhood (Atewologun & Singh, 2010). As in adolescence, ERI is associated with positive outcomes, particularly in adults under 40 (Smith & Silva, 2011), and centrality can buffer the negative psychological effects of discrimination (Yip et al., 2019). At the same time, some studies suggest exploration in adulthood may exacerbate the link between discrimination and psychological distress (Torres & Ong, 2010; Torres et al., 2011).

Summary of ERI Attitudes across Development and Future Directions

Ethnic-racial affect increases across early and middle childhood and varies in adolescence and adulthood with the role of influencers. Affect in particular has been inconsistently measured across developmental periods. Research is needed to clarify which ages require transition from the doll/picture task methodology used in childhood to the adaptations of adolescent versions of survey measures, and whether we are missing aspects of attitudes in middle childhood, given that the starting points for conceptualization and assessment have been in early childhood or adolescence. Doll study methods and adolescent measures of affect are not equivalent (Byrd, 2012); thus, researchers should explore whether some aspects of attitudes are currently being missed during middle childhood.

Little work has examined centrality in children, thus further research is needed. Researchers should also explore how the ability to sort and self-label is associated with the development of centrality as children internalize the meaning of ethnic-racial categories. Centrality appears to be stable in adolescence and adulthood; however, the role of implicit compared to explicit attitudes is understudied. For example, Marks et al. (2011) used innovative methodology to assess implicit forms of ERI and found interesting developmental trends as well as important differences between biracial and monoracial adolescents. In the study, biracial adolescents showed implicit hesitancy in deciding whether the word “white” could be used to describe them. For the students with the greatest heart rate reactivity while talking about their identities, these patterns were even more pronounced. In addition, recorded physiological markers of anxiety and implicit response time patterns were characterized by adolescents’ own words of confusion, hesitancy, and uncertainty about how their minority identities fit with a majority white identity.

Furthermore, longitudinal research needs to adopt more nuanced, within-person approaches. The lifespan model of ERI may be useful in assisting researchers in exploring how influencers (e.g., local current context or identity-relevant experiences) shape early affect and centrality. For example, children in racially homogenous neighborhoods may be more likely to identify strongly with other characteristics compared to those in diverse neighborhoods where ethnicity/race is more salient. In adulthood, research on attitudes needs to be extended beyond college students and explore how other adult contexts, like the workplace, and transitions between settings influence attitudes. For example, if adults are able to maintain more of their day-to-day lives and social connections after moving or changing jobs, their attitudes may be more stable than those of adults who need to develop a new social network. Finally, more research is needed to understand how attitudes vary within each developmental period and how attitudinal aspects of ERI might reflect continuity (or discontinuity) across periods.

The ERI Dimension of Behaviors

Ethnic-racial behaviors include individuals’ behavioral enactments (sometimes referred to as performances or role behaviors) of cultural values, styles, language use customs, and/or processes (e.g., exploring and resolving) involved in trying to gain a sense of one’s ethnic-racial groups(s).

Early Childhood

Young children may engage in ethnic-racial behaviors intentionally or unintentionally as a result of their environments (e.g., speaking Spanish because their family speaks to them in Spanish). Bernal et al. (1990) assessed role behaviors of preschool Mexican children by asking a series of yes/no questions (e.g., “Do you eat frijoles or beans at home?”, “Do you go to Mexico to visit your family?”). They found no age-related progression in the number of behaviors; however, they found growth over time in the cultural meaningfulness and ability to connect these behaviors to their ERI. Role behaviors are a precursor to knowledge: children may engage in behaviors at first with little understanding of their relevance, but later associate the behaviors with their group membership (Bernal et al., 1990).

Middle Childhood

Limited empirical attention has been given to ethnic-racial behaviors in middle childhood. However, behaviors such as language use, dress, and traditions are commonly cited by children in explaining what defines their ethnicity (e.g., Corenblum, 2014; Rogers & Meltzoff, 2017), which suggests that behaviors are important to children. However, the extent to which children in middle childhood have internalized these behavioral norms and engage in ethnic-racial role behaviors is unknown.

Two components of ERI behaviors that were originally developed with adolescents have been adapted for middle childhood, including exploration (i.e., initiating behaviors to learn more about one’s ethnic-racial background) and commitment, which has also been termed resolution involving gaining clarity about one’s ethnicity/race as part of one’s self-concept (see Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014 for review). However, the appropriate age period to test these components is less clear. To illustrate, although a study of 7-year-old children (Marcelo & Yates, 2019) found moderately high exploration and commitment using the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure-Revised (MEIM-R; Phinney & Ong, 2007), internal consistency was low, which calls into question the reliability of using the MEIM-R with this age group. However, adequate reliability was found with children in third to fifth grade (Hughes & Johnson, 2001) and children in fifth to eleventh grade (Zapolski et al., 2018). Similarly, using the Ethnic Identity Scale (EIS; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004), exploration and resolution showed adequate reliability with sixth to eighth graders (Rivas-Drake et al., 2017). Overall, it is unclear whether measures developed for adolescents and adapted for younger children are capturing their ethnic-racial behaviors with validity.

Adolescence

In adolescence, behaviors have primarily been studied as exploration and commitment/resolution. Longitudinal studies have been mixed, with some finding that exploration increases (e.g., Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010), decreases (e.g., Pahl & Way, 2006), or remains stable for early adolescents (average age 11) but increases for middle adolescents (average age 14; French et al., 2006). Whether exploration increases and decreases across adolescence may be based on a variety of individual factors, contextual factors, and identity-relevant experiences.

Further, adolescents often express commitment to an identity, but the progression from a diffuse, unexamined identity to identity commitment/resolution is not always linear or in one direction. Indeed, longitudinal research shows a mix of regression, stability, and progression (e.g., Kiang et al., 2010; Seaton et al., 2009). Thus, it may be more accurate to say that individuals move through cycles of commitment, such that they may come to a sense of clarity about identity at some points but later return to states of uncertainty, especially as they transition between contexts or roles (e.g., into adulthood).

Adulthood

College offers an important context for adults to engage in ERI behaviors and learn more about their groups. For example, ERI exploration appears to increase over the college years (Syed et al., 2007), as young adults are more likely to join ethnic student organizations and have same-race friends (Ethier & Deaux, 1994). However, these effects tend to be for those in 4-year colleges. Students in 2-year colleges are more likely to have a decline in exploration (Tsai & Fuligni, 2012), perhaps because of a lack of structured exploration opportunities. Few studies have examined ERI behaviors outside of college-attending samples, but even in older adulthood, identity-relevant experiences can relate to ERI shifts. For example, experiencing racism was related to engaging in more ethnic-racial behaviors for Black adults (Sherry et al., 2006). Being a parent may also increase adults’ participation in behaviors as they start to socialize their children.

Summary of ERI Behaviors across Development and Future Directions

ERI behaviors have primarily been assessed in early childhood although older children use behaviors to describe their ethnicity/race. A great deal of research is needed to understand behaviors across the lifespan in all ethnic-racial groups and the factors that influence their development. College is a particularly important context for adult ERI exploration, but research should also include more consideration of how individuals cycle through exploration and commitment/resolution throughout the lifespan and as a result of life events and interaction in other contexts, such as the workplace.

Although we proposed that exploration and commitment/resolution can reflect ERI behavior, it is unclear how these components map onto behaviors measured in childhood. Furthermore, it is not clear the minimum age at which exploration and commitment/resolution can be reliably measured. For example, as noted, some studies have found adequate reliability in assessing exploration and commitment/resolution in third to fifth grade (Hughes & Johnson, 2001) but not with seven-year-olds (Marcelo & Yates, 2019). Using the lifespan model, research could chart development of role behaviors, exploration, and commitment/resolution from early through late childhood and then into adolescence and adulthood.

The ERI Dimension of Knowledge

Ethnic-racial knowledge captures individuals’ working understanding of the behaviors, characteristics, values, and customs that are relevant to one’s ethnic-racial group(s). Notably, it is not the behaviors or characteristics themselves that comprise this dimension, but rather the conceptual understanding and meaning, as well as broader worldview, that might be attached to these ethnic-racial relevant markers.

Early Childhood

Children’s group knowledge is directly related to their abilities to categorize and self-label ethnic-racial group membership. It is important for children to understand the bounds of one’s group in order to come to a sense of what the group means to them. Research has tended to focus on young children’s ability to agree to or describe group-specific behaviors, such as Mexicans eating frijoles (i.e., beans) at home (e.g., Bernal et al., 1990). Studies suggest that 11 to 13% of Latinx preschoolers and 30% of kindergartners give ERI-relevant explanations (e.g., eating mole or frijoles, speaking Spanish at home) for their knowledge about what makes someone Mexican/Dominican (Bernal et al., 1990; Serrano-Villar & Calzada, 2016).

Middle Childhood

Generally, middle childhood is thought to mark a shift toward a more abstract understanding of ethnicity/race that is based on internal rather than external characteristics (Akiba et al., 2004; Quintana, 1998). Thus, knowledge about the boundaries and characteristics of one’s group becomes more complex. However, consistent with the influencers posited to shape ERI, this process may vary by individual factors. For example, in a study in which first grade children were asked to talk about themselves to peers in a different school, children of color described their ethnicity/race in terms of behavior (language use, dress, food, festivals and traditions) and appearance (Grace, 2008). Collectively, children in middle childhood have the capacity to understand a social identity such as ethnicity/race, but that capacity may manifest in different ways based on individual factors (e.g., ethnicity/race), and the meaning-making processes that individuals engage in around ERI.

Increasing knowledge allows children to consider the meaning and importance of their group membership by connecting what they have learned with their understanding of their personal and other social identities. For example, learning about important historical figures can promote personal and collective pride. Children’s behavioral engagement and developing awareness and affiliation also influence and interact with their knowledge.

Adolescence

Adolescents have greater knowledge compared to children (Quintana & Vera, 1999). In addition to ethnic-racial socialization from family and schools, the recent surge in internet and social media usage among adolescents provides a context for greater exposure to others who share one’s background and opportunities for race-centered discussions and connections (Tynes et al., 2018). It is possible that greater interaction with online contexts increases ERI knowledge, especially for adolescents in contexts with fewer individuals outside their family who share their ethnic-racial group(s).

Adulthood

In adulthood, knowledge may be more focused on understanding the ways one’s group culture shifts with the influence of younger people, societal trends, and national/international policies. For example, ethnic-racial ideology reflects one’s broader perceptions of what it means to be a member of one’s ethnic-racial group (Sellers et al., 1998). As it is complex and abstract, ideology is less often studied than other more easily assessed dimensions. Thus, few studies have examined how adults negotiate their knowledge of history and traditions with newer group-relevant information.

Summary of ERI Knowledge across Development and Future Directions

Research with Latinx children suggests that ERI knowledge is connected to understanding of ERI labels and behaviors. However, little work on knowledge has been conducted in other groups, and researchers have not addressed what aspects of knowledge might be most important for other components of ERI or other outcomes. Knowledge becomes more complex as children age and becomes connected to other aspects of ERI. However, future research should explore how contextual, individual, and identity-relevant experiences affect ERI knowledge throughout the lifespan.

More research is also needed on ideology and how it develops. Furthermore, exploration of how children, adolescents, and adults differentially negotiate multiple sources of information and changing trends and policies could be extremely fruitful. Interesting new directions have begun to explore how ERI knowledge might interact with other constructs such as political activism, critical consciousness, and collective action in support of multicultural goals (e.g., Hope et al., 2016; Mathews et al., 2019).

INTEGRATING THE LIFESPAN MODEL OF ERI: RECOMMENDATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The current paper presented a lifespan model of ERI. Drawing on prior theoretical and empirical scholarship, we extend the literature by offering a detailed discussion of how ERI takes shape within developmental periods that have tended to be overlooked in foundational work, and across developmental periods. We proposed ways in which ethnic-racial priming during infancy may prompt initial awareness of ethnicity/race that becomes differentiated across childhood and through adulthood. We outlined various ERI components that have been examined across developmental periods within five dimensions, including ethnic-racial awareness, affiliation, attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge. Although it is not feasible to provide a thorough review of all ERI components across the five dimensions and all influencers that have been tested to date in one paper, we highlight several examples of how existing work fits within the lifespan model and identify key areas for future research. As noted throughout, we conceive that the dimensions inform each other across development and are bidirectionally shaped by contextual and individual factors, developmental considerations, identity-relevant experiences, and meaning-making across development. In adopting this lifespan approach to ERI, several limitations in the existing literature became apparent, which highlight directions for future research.

Dimensions and Components

First, researchers have predominantly tested ERI dimensions within one developmental period, with less focus on how they evolve and fold into each other across developmental periods. For example, using different measures, ethnic-racial centrality has been tested in early childhood (e.g., Derlan et al., 2017), middle childhood (e.g., Rogers & Meltzoff, 2017), adolescence (e.g., Okeke et al., 2009), and adulthood (e.g., Hoffman et al., 2017); however, less attention has been given to understanding how early ERI components map onto later ERI components over time. Are individuals who have greater ethnic-racial centrality in childhood more likely to have greater ethnic-racial centrality in adolescence and adulthood? How does the form and magnitude change over time? How do these processes occur in linear vs non-linear ways? As these questions are investigated it will be important to examine how ERI components vary across periods alongside individuals’ meaning-making and developmental considerations.

On a related note, some components of ERI have only been considered relevant for one developmental period, and it is unclear which components extend across multiple periods and which components are truly limited to one developmental period. For example, ERI exploration has been tested in adolescence, but not in earlier developmental periods, while ERI constancy has been tested predominantly in childhood but less in later developmental periods. How can we assess and operationalize ERI exploration during childhood, or is this process exclusive to adolescence? Some components may be particularly salient at specific developmental periods, and less so at other developmental periods. We posit that components of ERI do not have equal salience across every aspect of development, and individuals may cycle through positive, close connections with their ethnicity/race, as well as negative, less close connections with their ethnicity/race. For example, awareness and affiliation may be more prominent during childhood while attitudes and behavior take on more significance in adolescence and adulthood. Additional questions are: How do components of ERI become more or less relevant based on individuals’ connections with other social identities that may play a greater role than ethnicity/race? Further, are there additional dimensions and components of ERI that we have not yet uncovered or conceived? Answers to these questions may become clearer as we use the lifespan model to understand ERI.

Our description of five ERI dimensions was an initial attempt to categorize components of ERI that have been assessed to date within each developmental period. However, it is important to recognize that ERI dimensions and components within them are not distinct, but rather overlap and inform each other. For example, in considering attitudes and behaviors, individuals with higher ERI affirmation, which is an attitude, are more likely to engage in ERI exploration (e.g., attending a cultural celebration), which is a behavior. Reciprocally, as individuals’ behaviors increase, this may affect their attitudes (Marks et al., in press). Research is needed to continue refining the five ERI dimensions and components within them with attention to their distinctive and overlapping nature.

Methodological Diversity and Innovation

Methodological innovations are needed to further drive ERI scholarship. First, advances in measurement of ERI across developmental periods have been uneven. For example, continued innovations are needed for measurement in early childhood, and there is limited research focusing on assessments of ERI in middle childhood. Often, youth in middle childhood are grouped with preschoolers or with adolescents (e.g., Pauker et al., 2017), and measures were often developed for preschoolers or adolescents (e.g., Zapolski et al., 2018), which may not accurately capture what ERI looks like and means during middle childhood.

Second, research on ERI development during adulthood is significantly lacking. Research in this developmental period has tended to focus on college students, many of whom are young adults. We know less about ERI development among adults who do not go to college and among older adults. Although some research has examined how parents’ ERI affects socialization processes with their children, and children’s developing ERI (e.g., Derlan et al., 2017), we must examine how other influencers play a role. As examples, how do individual factors (e.g., intersectional identities, skin tone, gender), local current contextual factors (e.g., becoming a grandparent, starting a new job with a different ethnic-racial composition of coworkers, moving to a more or less diverse environmental context), and the historical context (e.g., changes in political landscapes) influence adults’ ERI? Furthermore, new components of ERI that we have yet to theorize about may come onboard in adulthood.

Third, as noted, research on infants demonstrates awareness of ethnic-racial differences during the first year of life, indicating that important developmental processes occur long before children communicate about them explicitly. Moreover, there are implicit dimensions of ERI across the entire lifespan that function independently of explicit dimensions; however, apart from a few noteworthy studies (e.g., Marks et al., 2011 with adolescents), limited work has tested implicit dimensions of ERI outside of childhood. As we further our understanding of ERI across the lifespan, it is necessary to test both implicit and explicit dimensions of ERI.

Testing the Working Model

In addition to further refining the dimensions and components of ERI across the lifespan and advancing measurement and design, another important future direction is to test the factors that are posited to shape and be shaped by ERI as outlined in the lifespan model. Although some of our recommended future research directions call for longitudinal research, there are many research questions that can be answered with cross-sectional work. We posit that the lifespan model of ERI can be useful to theoretically ground studies that have one time point and multiple time points. Throughout the manuscript we highlighted examples of existing work that support aspects of the lifespan model, but more work is needed. For example, although some research has tested how identity-relevant experiences and contextual factors inform ERI within adolescence (e.g., how discrimination informs ERI exploration in adolescence; Pahl & Way, 2006), the ways in which these factors inform ERI in other developmental periods (e.g., early childhood or middle childhood) are less well understood.

Although we posit bidirectional relations between ERI and individual, developmental, contextual factors, and identity-relevant experiences, the majority of research has focused on how these factors influence ERI, rather than the reverse. For example, one’s neighborhood has been tested as a predictor of ERI, but it is possible that individuals’ engagement in ERI processes (e.g., exploration) may impact neighborhood choices. Although some work has examined bidirectional relations between ERI and identity-relevant experiences, such as socialization (Hoffman et al., 2017) and perceived discrimination (Seaton et al., 2009), more research on bidirectional relations between ERI and other influencers in the lifespan model is needed.

Finally, three particular areas must be addressed as research moves forward with the lifespan model of ERI. Specifically, this model must be examined with attention to (a) multiracial/multiethnic individuals, (b) White individuals, and (c) the intersection of multiple social identities. ERI conceptualization and research to date has been biased toward a monoracial or monoethnic experience, as one that is only relevant to individuals of color, and as a singular identity (Rogers et al., in press). Scholars have highlighted and demonstrated that individuals have various identities, and can form a healthy sense of self via an identity other than ERI (Cross & Fhagen-Smith, 1996; Rogers & Meltzoff, 2017). Understanding the variability in individuals’ experiences, and the factors that contribute to variability in individuals’ sense of self, both in terms of ethnicity/race, apart from ethnicity/race, and in combination with ethnicity/race is important. Although some ERI dimensions and the factors that bidirectionally inform them may be similar across populations, there are also differences that must be assessed across the lifespan to develop a more comprehensive understanding of individuals’ varied experiences.

Conclusions

ERI research has grown exponentially in recent decades. This body of knowledge has provided important insight into the associations between ERI and a host of psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes (e.g., Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). However, given that existing work and interventions have, for the most part, taken a period-specific, rather than lifespan approach, we are only beginning to uncover the surface of implications that ERI has for development. There are various gaps to address in future work, particularly with respect to refining the five ERI dimensions and components across development, measurement, and testing the tenets of the model. Moving forward with the lifespan model of ERI will enable us to unite disparate work that has evolved in developmental silos, and stimulate future research and programming on ERI across the lifespan.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

FUNDING

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1729711.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Contributor Information

Chelsea Derlan Williams, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Christy M. Byrd, North Carolina State University

Stephen M. Quintana, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Catherine Anicama, West Coast Children’s Clinic.

Lisa Kiang, Wake Forest University.

Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Harvard University

Esther J. Calzada, University of Texas at Austin

María Pabón Gautier, St. Olaf College.

Kida Ejesi, Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School.

Nicole R. Tuitt, University of Colorado

Stefanie Martinez-Fuentes, Arizona State University.

Lauren White, University of Michigan.

Amy Marks, Suffolk University.

Leoandra Onnie Rogers, Northwestern University.

Nancy Whitesell, University of Colorado.

REFERENCES

- Aboud FE (1988). Children and prejudice. B. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE, & Skerry SA (1983). Self and ethnic concepts in relation to ethnic constancy. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 15(1), 14–26. 10.1037/h0080675 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba D, Szalacha LA, & García Coll CT (2004). Multiplicity of ethnic identification during middle childhood: Conceptual and methodological considerations. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2004(104), 45–60. 10.1002/cd.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul I, Oyserman D, & Bybee D (2006). Racial-ethnic identity in mid-adolescence: Content and change as predictors of academic achievement. Child Development, 77(5), 1155–1169. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzures G, Quinn PC, Pascalis O, Slater AM, Tanaka JW, & Lee K (2013). Developmental origins of the other-race effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(3), 173–178. 10.1177/0963721412474459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]