Abstract

Background:

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is an inflammatory disease that has a papulosquamous morphology in areas rich in sebaceous glands such as the scalp, face, and body folds. Petaloid SD is an uncommon presentation found in patients with dark skin (Fitzpatrick Skin type V-VI). This form of SD can appear as pink or hypopigmented polycyclic coalescing rings or scaly macules and patches in the typical areas SD appears, which can mimic other conditions including lupus erythematosus. There is significant disproportion in the representation of darker skin types in dermatological textbooks and scarce literature on petaloid SD. This case demonstrates the presentation of the petaloid SD in an African American patient to contribute to the limited literature on dermatological conditions within this population.

Case Report:

A 25-year-old African American female with a history of mild hidradenitis suppurativa and asthma who presented with asymptomatic hypopigmented rashes throughout her face, scalp, and chest. She was diagnosed with the petaloid form SD and treated with ketoconazole shampoo once weekly, ketoconazole cream 1-2x daily, and hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment twice daily as needed. At six-week post-treatment follow-up, the patient's rashes significantly improved.

Conclusions:

The petaloid form of SD is commonly experienced in dark-skinned patients. While common treatments for SD are effective in this form of SD, special consideration of skin types, skincare habits, and haircare in the African American population should be explored. This case report demonstrates how this uncommon skin condition presents in patients of Fitzpatrick skin type V-VI and a successful treatment course.

Keywords: Seborrhea-Like Dermatitis with Psoriasiform Elements (C565217), 17-Hydroxycorticosteroids (D015065) Ketoconazole (D007654), Petaloid Seborrheic Dermatitis, Fitzpatrick V-VI, Skin of Color

INTRODUCTION

Skin conditions often create social and psychological distress to patients. Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is ranked third behind atopic and contact dermatitis as skin conditions with potential to impair quality of life. SD is an inflammatory disease that has a papulosquamous morphology in areas rich in sebaceous glands such as the scalp, face, and body folds [1]. Potential etiologies are disruption of the skin’s microbia, Malassezia species, increased presence of unsaturated fatty acids on the skin surface, or disruption of the cutaneous neurotransmitters [1]. Differential diagnoses include atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, secondary syphilis, tinea faciei, discoid lupus, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, sarcoidosis, and fungal infection [1-2]. Diagnosis of SD is often made clinically by the distribution of lesions and appearance. Dermatopathology is not necessary due to the absence of histologic features that are exclusively characteristic or pathognomonic of SD. However, evaluations with a potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopic exam of skin scrapings, swab for microscopy/culture, histology and direct immunofluorescence, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) serology can be helpful in differentiating the diagnoses [1].

Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis commonly consists of topical corticosteroids, salicylic acid, selenium sulfide, and antifungal creams [3]. The petaloid seborrheic dermatitis frequently presents in people with dark skin (Fitzpatrick Skin type V-VI). These lesions appear to be polycyclic coalescing rings that are slightly pink or hypopigmented and may form arcuate or petal-like patches [2-3]. While diagnosis of these dermatoses is not always difficult to make, special considerations in patients with darker skin should be acknowledged such as hair type, hair washing frequency, and tendency for hypopigmentation [3]. There is limited literature on the petaloid form of SD that tends to be restricted to dark-skinned individuals. We present a case of petaloid form seborrheic dermatitis in a young African American female, who responded well to topical antifungals and steroids.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old female with Fitzpatrick skin type V-VI, and history of mild hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), tobacco use, and asthma presented to the clinic with asymptomatic hypopigmented rashes throughout her face, scalp, hairline, and chest (Figure 1 & 2). She had intermittent scaly rashes in these areas over the past 1-2 years, but all were previously milder. The patient had no eruptions elsewhere except for occasional Hurley Stage-1 HS inflammatory lesions in the axilla/groin area. For her HS, she was treated with topical benzoyl peroxide wash daily, doxycycline 100 mg daily, and clindamycin phosphate 1% solution to inflammatory lesions daily as needed. However, the patient reported never using clindamycin nor the known irritant, benzoyl peroxide, on her face. Other medications included albuterol and fluticasone inhalers. The patient had no other medical risk factors, no known allergies, and her rapid plasma reagin (RPR) workup was negative for syphilis. The differential diagnosis included tinea corporis, pityrosporum (tinea versicolor), lupus erythematosus, secondary syphilis, or the petaloid form of seborrheic dermatitis. Histopathology of SD is usually nonspecific therefore biopsy was not obtained. Moreover, as the eruption involved the face, we did not wish to subject the patient to a procedure which would result in scarring. Based on a negative KOH scraping, non-reactive RPR syphilis test and the clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with the uncommon petaloid form of seborrheic dermatitis.

Figure 1.

Initial presentation of patient with thin annular scaly plaques on face and forehead.

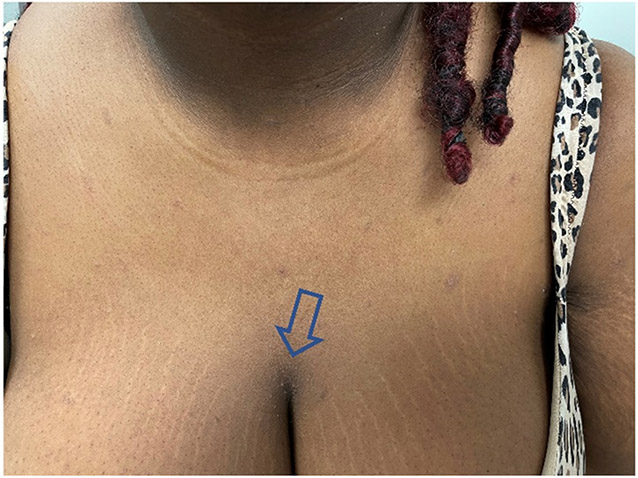

Figure 2.

Initial presentation of patient with intramammary involvement of thin scale on the chest (see arrow).

The patient was started on ketoconazole shampoo once weekly, ketoconazole cream 1-2 times daily PRN, and hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment daily. At her 6-week post-treatment follow up, the patient's dry scales were significantly diminished, although some areas of hypopigmentation were still noted (Figure 3). The patient continued the treatment and at latest follow up (~6 months) her skin does not demonstrate any abnormalities (not shown). This case demonstrates an uncommon presentation of seborrheic dermatitis in a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type V-VI that was successfully treated with conservative topical treatments.

Figure 3.

Patient with improvement noted at six weeks following treatment. Please note lack of scarring at the sites of initial rash.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common, chronic, benign inflammatory skin disease that affects all ethnic groups in all regions globally [1]. SD usually has a bimodal presentation, infancy and middle-age adulthood. In adults, SD most commonly involves the face, scalp, and chest. In children, SD usually appears in the second week of life in areas such as face, diaper region, skin creases of the neck and the axillae. Infantile SD is also known as cradle cap when presented on the scalp with thick, dry, silvery or yellow scales [1]. In an overview of the epidemiology of skin diseases in people of color, the 12 leading dermatological diseases in African Americans or Blacks are acne vulgaris, eczema, fungal infections, urticaria, scabies, impetigo, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and verrucae vulgaris [4]. Of note, seborrheic dermatitis was also one of the most common cutaneous diseases in the African American pediatric population [4]. Two other reports of most common dermatologic conditions in patients of color also indicate that seborrheic dermatitis is one of the top five most common diagnoses in this population [5-6]. Other research has shown that there may be a slight increase in incidences of SD among African Americans and West Africans (2.9-6%) compared to Caucasian skin [7]. As studies show, SD is a dermatologic concern frequently encountered by people of color. However, a review of dermatological textbooks found the most common skin types depicted are Fitzpatrick types II-III [8]. By the authors’ search, there are scarce reports of the petaloid form of SD in the published literature. The presentation of this case will alert practitioners to this entity to allow easier recognition of this diagnosis without having to subject the patient to potentially scarring procedures such as a skin biopsy to rule out other entities such as lupus erythematosus, tinea faciei, and facial discoid dermatitis. This calls for an increased representation and understanding of dermatological conditions in darker skin types.

Skin lesions appear in various ways in different skin types, and thus a thorough understanding of presentations offers the most competent care for patients of all skin types. The petaloid form of seborrheic dermatitis is frequently associated with people with dark skin (Fiztpatrick skin type V-VI) [2]. As seen in our patient, the lesions appear as polycyclic coalescing rings that are light pink or hypopigmented [3]. The hypopigmentation without scarring is thought to result from inhibition of melanocyte tyrosinase function and pigment production by yeast metabolites [9]. Unlike the common presentation of scaly rashes, patients of darker skin usually do not often show significant scale. In addition, the underlying erythema of SD may be difficult to appreciate in darker skin [2]. Lesions on the anterior chest and face tend to have a psoriasiform morphology in petaloid SD, making psoriasis a common mimicking diagnosis for petaloid SD in skin of color [1]. Annular facial dermatoses in Fitzpatrick skin type V-VI can also closely resemble lesions of secondary syphilis, although presence of lesions only on the face and not a widespread eruption including the palms and soles would be unusual [2, 10]. Another interesting variant of SD presents similarly to cutaneous sarcoidosis and is more likely to be encountered in African American patients [11]. Cutaneous discoid lupus may progress into hypopigmented lesions similar to petaloid SD, however, the hypopigmentation occurs late in the chronic disease and is associated with scarring. Majority of discoid lupus appear as erythematous, inflamed plaques with well-demarcated hyperpigmentation at the periphery and depressed central atrophy [12]. Fungal dermatoses, including tinea corporis, usually present with an itchy, red rash on the neck, trunk, or extremities. These lesions also demonstrate sharp marginations with a raised erythematous scaly edge that may contain vesicles. KOH preparations showing septae and branching hyphae can confirm the diagnosis [13]. Conversely, SD rashes are commonly flat patches without severe inflammation on the margins. The unique dermatological presentations in patients of color can contribute to difficulties in timely and accurate diagnosis. In our patient with negative syphilis and fungal testing, characteristic presentation of SD lesions, and insignificant past medical history, SD was the most likely diagnosis and treatment was promptly started.

Treatment goals for SD is primarily to lessen visible signs and reduce symptoms such as pruritus and erythema. Common treatment includes over-the-counter shampoos and topical antifungals, calcineurin inhibitors, and corticosteroids [14]. The efficacy of ketoconazole shampoo in clearing scalp SD and dandruff and preventing relapse has been established since the early 1990s [15]. A more recent multicenter, double-blind, parallel group study showed that miconazole nitrate shampoo is at least as effective and safe as ketoconazole shampoo for treating SD in the scalp [16]. While similar treatment may be used in skin of color, considerations of hair and skin type, hair-washing frequency, and inappropriate oil use in people of color may alter the outcomes of treatment [3, 17]. In addition, SD in people of color are associated with hair breakage, lichen simplex chronicus, and folliculitis requiring careful utilization of antidandruff shampoos. Encouraging patients to increase shampooing and decrease use of scalp pomades and oils has been recommended [17]. Further, chronic use of corticosteroids may exacerbate hypopigmentation commonly seen in patients of color with SD. A pilot trial showed 1% pimecrolimus cream, a calcineurin inhibitor, as an excellent alternative therapy for treating SD in African Americans, particularly in those with associated hypopigmentation [18]. However, like corticosteroids, some authors feel that calcineurin inhibitors should only be used short-term in conjunction with antifungal shampoos and topicals [12, 19]. Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic and relapsing condition; therefore, prevention and prophylaxis management are important.

CONCLUSION

A paucity of literature exists on the petaloid form of seborrheic dermatitis, which is usually encountered only in dark-skinned patients. It is important to recognize and understand the presentation and treatment of petaloid SD seen in people of color to facilitate culturally competent care. SD in dark skinned individuals with scaly, hypopigmented macules and patches in typical areas of involvement such as the face, scalp, hairline, beard, sternum, and other skinfolds [3]. Uniquely, these lesions may appear annular or petal-like, given the term petaloid SD. Petaloid SD in skin of color may be similar to other hypopigmented skin conditions, however, clinical judgment with thorough history should differentiate the diseases. In rare cases, a skin scraping or biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis or to rule out other etiologies. Treatment for this form of SD is similar to the typical SD medications, which includes antifungal topicals and shampoos, corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors. However, special considerations of different skin type, skincare habits, and hair-care in this population should be explored as these factors can affect the dermatological manifestation and outcome for these patients. Excessive hair oil and pomade use, and infrequent hair-washing may exacerbate SD in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types V-VI, and should be discussed with patients. There is a significant disproportion in the representation of darker skin types in dermatological textbooks. This case demonstrates the presentation of the petaloid form SD in an African American patient to contribute to the limited literature on dermatological conditions within this population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial assistance of the Wright State University Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology. This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL062996 (J.B.T.), R01 ES031087 (C.A.R., J.B.T.).

ABBREVIATIONS:

- SD

Seborrheic dermatitis

- KOH

potassium hydroxide

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- VDRL

Venereal Disease Research Laboratory

- HS

hidradenitis suppurativa

- RPR

rapid plasma reagin

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors state no conflict of interest

REFERENCES:

- 1.Tucker D, Masood S. Seborrheic Dermatitis. [Updated 2022 Aug 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551707/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meffert JJ. Photo quiz. Flowering dermatosis. Am Fam Physician. 1998. Jun;57(11):2805–6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9636342/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elgash M, Dlova N, Ogunleye T, Taylor SC. Seborrheic Dermatitis in Skin of Color: Clinical Considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019. Jan 1;18(1):24–27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30681789/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor SC. Epidemiology of skin diseases in people of color. Cutis. 2003. Apr;71(4):271–5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12729089/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007. Nov;80(5):387–94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18189024/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, Huang W, Pichardo-Geisinger RO, McMichael AJ. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012. Apr;11(4):466–73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22453583/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halder: Halder RM, Nootheti PK. Ethnic skin disorders overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6):S143–S148. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12789168/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reilley-Luther J, Cline A, Zimmerly A, Azinge S, Moy J. Representation of Fitzpatrick skin type in dermatology textbooks compared with national percentiles. Dermatol Online J. 2020. Dec 15;26(12):13030/qt91h8k9zc. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33423414/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diane: Diane J-R, Amit GP. Dermatology Atlas for Skin of Color. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaurin CI. Annular facial dermatoses in blacks. Cutis. 1983. Oct;32(4):369–70, 384. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6226493/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedmann DP, Mishra V, Batty T. Progressive Facial Papules in an African-American Patient: An Atypical Presentation of Seborrheic Dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018. Jul;11(7):44–45. Epub 2018 Jul 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30057666/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowell NR. Laboratory abnormalities in the diagnosis and management of lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1971. Mar;84(3):210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb14209.x. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4102091/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yee G, Al Aboud AM. Tinea Corporis. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544360/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015. Feb 1;91(3):185–90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25822272/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peter RU, Richarz-Barthauer U. Successful treatment and prophylaxis of scalp seborrhoeic dermatitis and dandruff with 2% ketoconazole shampoo: results of a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 1995. Mar;132(3):441–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb08680.x. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7718463/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buechner SA. Multicenter, double-blind, parallel group study investigating the non-inferiority of efficacy and safety of a 2% miconazole nitrate shampoo in comparison with a 2% ketoconazole shampoo in the treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014. Jun;25(3):226–31. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.782092. Epub 2013 May 21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23557492/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, Heath C, McMichael AJ, Ogunleye T, Callender V. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017. Jul;100(1):31–35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28873105/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.High WA, Pandya AG. Pilot trial of 1% pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in African American adults with associated hypopigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006. Jun;54(6):1083–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.011. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16713477/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger TG, Duvic M, Van Voorhees AS, VanBeek MJ, Frieden IJ; American Academy of Dermatology Association Task Force. The use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in dermatology: safety concerns. Report of the American Academy of Dermatology Association Task Force. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006. May;54(5):818–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.054. Erratum in: J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Aug;55(2):271. VanBeek, Marta J [added]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16635663/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]