Abstract

Although ulcerative colitis [UC] shares many common pathways and therapeutic options with Crohn’s disease [CD], CD patients are four times more likely to undergo surgery 10 years into their disease in the biological era and are more likely to have extraintestinal manifestations than UC patients. Early treatment in CD has been demonstrated to modify the natural history of the disease and potentially delay surgery. Previous reviews on this topic have borrowed their evidence from CD to make UC-specific recommendations. This review highlights the emergence of UC-specific data from larger cohort studies and a comprehensive individual patient data systemic review and meta-analysis to critically appraise evidence on the utility of early escalation to advanced therapies with respect to short-, medium-, and long-term outcomes. In UC, the utility of the early escalation concept for the purposes of changing the natural history, including reducing colectomy and hospitalizations, is not supported by the available data. Data on targeting clinical, biochemical, endoscopic, and histological outcomes are needed to demonstrate that they are meaningful with regard to achieving reductions in hospitalization and surgery, improving quality of life, and minimizing disability. Analyses of different populations of UC patients, such as those with ‘relapsing & remitting’ disease or with severe or complicated disease course, are urgently needed. The costs and risk/benefit profile of some of the newer advanced therapies should be carefully considered. In this clinical landscape, it appears premature to advocate an indiscriminate ‘one size fits all’ approach to escalating to advanced therapies early during the course of UC.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, escalation to advance therapies, disease duration, early escalation

1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis [UC] is the most prevalent form of inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]. It occurs across all ages, sexes, and races, and is a global disease that impacts both developed and developing countries.1

Whilst sharing many common pathways and therapy options with Crohn’s disease [CD], there are number of key differences. Generally, patients with UC experience mucosal inflammation whereas there is transmural involvement of the gastrointestinal mucosa in CD patients. As a result, patients with CD are more likely to develop stricturing and penetrating phenotypes, have a higher likelihood of developing extraintestinal manifestations, and, 10 years into their disease course, ~40–60% of CD patients will require surgical resection as compared to a lifetime colectomy risk in UC of ~10–15%.2–4 Nonetheless, large epidemiological studies have identified that some patients with CD will experience a more indolent course and accurately differentiating those patients with progressively bowel-damaging CD from those with non-progressive phenotypes is a research priority.5 Despite these important differences between CD and UC, treatment strategies aimed at escalating to advanced therapies early in the disease course, commonly defined as ‘window of opportunity’ within 2–3 years of diagnosis, are often adapted from management of CD to that of UC.6 However, whether this concept is valid in UC is unclear.

In recent years, the goal of therapies in UC has shifted away from focusing on only controlling symptoms to also achieving objective measures of disease remission with the goal of modifying the natural history of the disease.7 Whilst in randomized controlled clinical trials [RCTs], clinical remission, endoscopic improvement, and histological healing are assessed as critical endpoints, sustained corticosteroid-free remission, and a reduced risk of hospitalizations and surgery also constitute relevant long term treatment targets in clinical practice.8,9

Early treatment in CD has been demonstrated to potentially modify the natural history of the disease and delay surgery.10 However, this has been less well evaluated in UC. In this review, we appraised the evidence of whether escalation to advanced therapies early in the disease course leads to improvement in both short-, medium-, and long-term outcomes in UC patients.

2. Current Treatment Options

Most patients with UC can be managed in the outpatient setting and treated successfully with both conventional and advanced therapies [Table 1].

Table 1.

Therapeutic landscape in ulcerative colitis.

| Mode of action | Drugs | |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional therapies | ||

| 5-ASA | Precise mechanisms of action unknown, act on numerous pathways and enzymes that promote colonic inflammation; have been shown to inhibit lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase enzymes, reduce the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes, and can scavenge reactive oxygen intermediates, inhibit the activation of transcription factor NF-kB.71 | Mesalazine, olsalazine, balsalazide, sulfasalazine |

| Corticosteroids | Inhibit transcription factors that control synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators, including macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes, mast cells, and dendritic cells. Inhibit genes responsible for expression of, among others, phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase-2, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α Budesonide is a corticosteroid with a high level of topical anti-inflammatory activity and low systemic bioavailability |

Prednisone, prednisolone [systemically acting] Budesonide, beclomethasone [topically acting] |

| Immunomodulators | The drug exerts its effect by, among others, triggering cell-cycle arrest, inhibiting T-lymphocyte signalling, targeting NF-kB, and promoting T-lymphocyte apoptosis, downregulating pro-inflammatory and gut-homing factors | Azathioprine, mercaptopurine, methotrexate |

| Advanced therapies | ||

| Lymphocyte trafficking blockade | Anti-α4β7 integrin S1P modulators |

Vedolizumab, ozanimod, etrasimod |

| Cytokine targeting or blockade | Anti-TNF Anti-IL-12/23 agents or anti-IL-23p19 agents |

Infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol Ustekinumab, mirikizumab |

| Intracellular signalling pathway blockade | Janus kinase inhibitors [JAK] | Tofacitinib [non-selective JAK, filgotinib [JAK 1 inhibitor], upadacitinib [JAK 1 inhibitor] |

2.1. Use of conventional therapies in UC

Five-aminosalicylic acid [5-ASA] drugs that include mesalazine, sulfasalazine, olsalazine, and balsalazide, administered either orally, rectally, or in combination, remain the mainstay first-line therapy for most patients with UC.11 A network meta-analysis has shown mesalazine, diazo-bonded 5-ASAs, and sulfasalazine all to be significantly superior to placebo for the induction and maintenance of clinical remission in patients with active UC, including both in patients with distal and extensive colitis.12,13 All the various drug formulations appear to have similar clinical efficacy, although a dose–response relationship is observed with 5-ASA formulations administered orally.12,13 Given their favourable efficacy and safety profile, even at maximum doses, and depending on the healthcare setting, as many as 70% of all UC patients may be managed with 5-ASAs in the long term.14

In patients whose disease is not controlled with 5-ASA therapy, oral systemic and topical corticosteroids are recommended for induction of remission.8,9,15 These agents are effective as short-term therapy, but their side-effect profile makes them unsuitable for long-term use, and there is limited data to suggest that long-term corticosteroid exposure maintains endoscopic remission. Chronic use of corticosteroids is associated with increased susceptibility to infections, serious and opportunistic infections, delayed wound healing, reactivation of hepatitis B or latent tuberculosis, osteoporosis, aseptic joint necrosis, and adrenal insufficiency.16,17 Other complications that have been associated with corticosteroid use include worsening of diabetes, dyslipidaemia, or hypertension, mood lability, ocular complications such as glaucoma and subcapsular cataracts, and an increased risk of cleft palate among infants born to mothers exposed to corticosteroids during the first trimester.

Traditional immunomodulators, such as azathioprine, mercaptopurine, and methotrexate, may be used as the next step in the therapeutic escalation algorithm, although azathioprine is used most frequently.18 It is recommended in corticosteroid-dependent patients who have failed or are intolerant to 5-ASA for maintenance of remission in corticosteroid-dependent UC.18 Immunomodulators also have an important role as add-on therapies, especially for patients treated with tumour necrosis factor [TNF] antagonists. Data from the UC-SUCCESS trial demonstrate that combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy, and observational data have suggested that immunomodulators reduce the relatively high risk of immunogenicity associated with TNF antagonist monotherapy. The use of azathioprine, however, is being questioned given limited efficacy, issues with tolerance, and potential for serious side effects, including risk of myelotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, thiopurine-induced pancreatitis, and risk of malignancy.18 Although cumulative use of immunomodulators of as high as 35% has been described in some cohort studies of UC patients, it is likely that the future of immunomodulators for management of UC will continue being rather limited given the ever-increasing armamentarium of advanced therapeutic options coming to the market.19

2.2. Use of advanced therapies in UC

The arrival of biological agents and small molecules has led to significant advances in the management of patients with UC. Advanced therapies fall into the following classes: cytokine targeting or blockade, intracellular signalling pathway blockade, and lymphocyte trafficking blockade.

Advanced therapies fill an unmet need in patients who fail 5-ASA and immunomodulators, have side effects, are intolerant to conventional therapies, or are resistant to corticosteroids. The relatively low risk of some side effects [e.g. infection] with long-term use is another potential advantage of some advanced therapies, particularly anti-integrin and anti-IL12/23 treatments. Several RCTs have now provided evidence of the efficacy and safety of biological agents and small molecules. These studies were summarized in a recent meta-analysis in 2022 that included data on 10 061 patients with moderate-to-severe UC.20 The study found significant efficacy across the board for all agents analysed including infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, etrolizumab, tofacitinib, filgotinib, upadacitinib, and ozanimod compared to placebo. Upadacitinib was significantly superior to the other interventions for the induction of clinical remission, whilst vedolizumab and subcutaneous infliximab ranked highest for the maintenance of clinical remission over 26–66 weeks.

3. Use of Biologics Early in the Course of UC

The benefits, including delaying surgery and disease progression, from early escalation to biological treatments in CD have generated interest in implementing this approach in UC as well. In contrast to CD, for which early disease is defined by the experts as that within 18–24 months of diagnosis, there is currently no consensus definition of ‘early disease’ for UC.21 The retrospective UC studies discussed below used a time span from 16 months to 3 years after diagnosis as a cut-off point for early treatment.

The evidence for the use anti-TNF and vedolizumab early in UC course is summarized below. Evidence for other advanced therapies is currently lacking. Whenever the data on CD were given in the same publication, these data are also discussed, especially if the differences in various outcomes were observed in CD but not UC patients.

3.1. Short-term outcomes

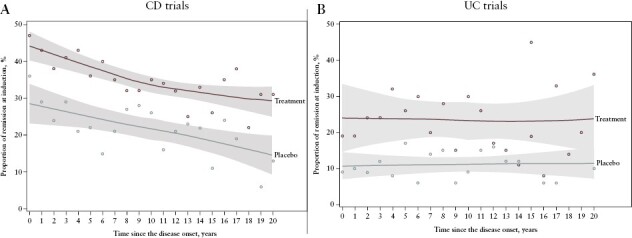

Prospective, controlled trials specifically designed to address the utility of early escalation with respect to short-term outcomes are lacking. However, a recent individual patient data meta-analysis of 11 and nine placebo-controlled RCTs of anti-TNF and anti-integrin biologics in CD and UC, respectively, examined the relationship between disease duration and post-induction clinical remission rates observed in these studies.22 The authors first compared the rates of clinical remission in patients with disease duration ≤18 months with those with >18 months of disease and found that in CD, pooled drug-induced and spontaneous remission rates were higher in patients treated earlier in a disease course when compared to treatment later in a disease course [pulled odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.09–1.64], but no such difference was observed in UC. Given that data for different temporal cut offs were similar, the authors examined the relationship between clinical remission rates and disease duration as a continuous variable. Whilst the drug-induced and spontaneous remission rates decreased with increasing disease duration in CD, the remission rates remained stable irrespective of the duration of disease in UC [Figure 1]. These data argue against a concept of a defined window of opportunity in both CD and UC, but are potentially more consistent with our understanding of the more progressive nature of CD when compared to UC. Although a relatively large number of patients [6168 patients with CD and 3227 with UC] and the relationship between C-reactive protein [cut off of >10 mg/L] and disease duration were examined, the data were not stratified on other possible risk factors, such as presence of extra-intestinal manifestations. Therefore, it may still be possible that certain groups of UC patients may require escalation to advanced therapies early in the disease course, but data on predicting which patients are in this subgroup are lacking.

Figure 1.

Rate of remission induction by duration of disease at initiation of treatment for [A] CD and [B] UC trials. Dots denote the proportion of an outcome averaged per the respective year.22 Reprinted from Ben-Horin S, Novack L, Mao R, et al. Efficacy of biologic drugs in short-duration versus long-duration inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and an individual-patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterology 2022;162:482–94.

3.2. Medium-term outcomes [follow-up of 5 years or less]

The limited number of studies on the utility of early escalation to advanced therapies, when examining medium-term outcomes, typically involve retrospective analyses of real-world evidence, often from claims databases, with follow-up periods of 5 years or shorter. Without the benefit of randomization in this setting, it is likely that early users of anti-TNF differ from late users with respect to various characteristics, such as the burden of inflammation, which are difficult to fully adjust for.23 Whilst earlier studies included only modest numbers of patients, their results do not appear to differ from those of larger studies carried out more recently [Table 2].

Table 2.

Real-world evidence on utility of early vs late escalation to advanced therapies.

| Study | No benefit for the outcomes | Definition of early disease | Follow-up duration | Patient numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandel et al. 2014 | Hospitalization rates | ≤3 years | n = 42 | |

| Nuij et al. 2013 | Abscess formation, fistula formation, extraintestinal manifestations, mucosal healing, or surgery over a median | ≤16 months | Median of 39 months | n = 27 |

| Ma et al. 2016 | Colectomy, UC-related hospitalization, clinical secondary loss of response | ≤3 years | Median of 175.6 weeks | n = 115 |

| Faleck et al. 2019 | Clinical remission, corticosteroid-free remission, endoscopic remission | ≤2 years | 6 months | n = 437 |

| Han et al. 2020 | Need for colectomy, UC-related emergency room visits, UC-related hospitalization or new corticosteroid use | ≤2 years | 1.7 years | n = 698 |

| Targownik et al. 2022 | Hospitalization rates, adjusted cumulative rate of IBD hospitalizations, or all-cause hospitalizations, or surgery | ≤2 years | Up to 5 years | n = 318 |

Mandel et al. retrospectively analysed hospitalization rates from in- and outpatient records of 42 consecutive UC patients.24 The indication for initiation of anti-TNF therapy for patients with UC included corticosteroid-refractory acute severe colitis, moderate-to-severe disease activity despite 3 months’ adequate dose of oral corticosteroid and immuno-suppressive therapy, or corticosteroid dependency. The authors found no benefit of early TNF antagonist initiation [within 3 years from diagnosis] in patients with UC, 64% of whom used corticosteroids during the anti-TNF treatment, but a 40% reduction in hospitalization rates in 152 CD patients.

Medical charts of newly diagnosed IBD patients in the population-based Delta cohort were retrospectively analysed to identify those with UC starting anti-TNF treatment within 16 months after diagnosis [early] and later than 16 months after diagnosis [late].25,26 Among the small number of UC patients, 16 received early and 11 received late treatment with anti-TNF. UC and CD patients were analysed together because of the small patient numbers. When compared with starting anti-TNF late in a disease course, there was no evidence that starting anti-TNF early in a disease course was associated with improvement in outcomes such as abscess formation, fistula formation, extraintestinal manifestations, mucosal healing, or surgery over a median follow-up of 39 months.

A retrospective analysis of physician office-based electronic records and a region-wide electronic healthcare database in Alberta, Canada, included 115 patients with UC (median follow-up was 175.6 weeks [IQR 72.4–228.4 weeks]).23 Primary non-responders to anti-TNF induction therapy and inpatients were specifically excluded to minimize the heterogeneity of the cohort and limit the effect of disease severity on selection bias towards early anti-TNF initiators. Early initiation of anti-TNF therapy [infliximab or adalimumab] was defined as initiation within the first 3 years of diagnosis, which was recorded for 57 patients. Early initiators had slightly more active disease [mean Mayo score 2.5 vs 1.9], and there was a trend towards a more concurrent corticosteroid use at anti-TNF induction in early when compared to late initiators. Within the 3 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences between the two groups in the rates of colectomy, UC-related hospitalizations, or clinical secondary loss of response. The authors concluded that although early anti-TNF treatment has a role as rescue therapy in severe or fulminant UC, other therapeutic options should be optimized for patients with mild-to-moderate disease.

A relatively large retrospective analysis of a mixed population of 437 patients with UC included in the VICTORY registry and treated with vedolizumab assessed potential differences in outcomes between patients with short UC duration [≤2 years] and those with longer disease duration.27,28 Thirty-two per cent of patients had severe disease, 48% of patients were corticosteroid-refractory, and 56% of patients had a history of TNF-antagonist failure. In this population, rates of clinical remission, corticosteroid-free remission, and endoscopic remission at 6 months did not differ between UC patients initiating treatment with vedolizumab early in a disease course when compared to those initiating treatment at a later point in their disease. In contrast, after adjusting for disease-related factors including previous exposure to TNF antagonists, CD patients initiating treatment with vedolizumab early in a disease course were more likely to achieve clinical remission, corticosteroid-free remission, and endoscopic remission when comparted to patients with treatment initiation at a later point.

A large, retrospective analysis of Korean National Health Insurance claims aimed at determining if the early initiation of anti-TNF therapy within 2 years of UC diagnosis affected the need for colectomy, UC-related emergency room visits, UC-related hospitalization, or new corticosteroid use during a follow-up period of 1.7 years.29 The analysis included 698 patients, of whom 399 were early and 299 late [>2 years] initiators of anti-TNF therapy. Patients using anti-TNF therapy for <6 months or with a history of colectomy before starting anti-TNF therapy were excluded. A greater proportion of patients initiating anti-TNF early in a disease course were on corticosteroids when compared to those initiating this therapy later in a course of their disease [44% vs 32%], whilst immunomodulators were used by around 43% in both groups. There were no significant differences in the risk of any of the analysed outcomes between early and late initiators of anti-TNF therapy within the follow-up period examined.

Recently, Targownik et al. published a retrospective chart analysis of secondarily collected claims data on UC patients from the Manitoba Health database, which covers nearly all residents of the Canadian province of Manitoba.30 Of the 318 included patients, 123 received anti-TNF therapy within 2 years of diagnosis. Data were analysed for a period of up to 5 years after treatment initiation. No information about disease severity was provided. After 5 years, there was no significant difference in hospitalization rates, adjusted cumulative rate of IBD hospitalizations, or all-cause hospitalizations between early and late initiators. Similarly, surgery rates were not different between early and late anti-TNF initiators in all years of follow-up, and IBD-specific as well as overall outpatient visits occurred at similar rates in early and late anti-TNF initiators. The authors also compared data on the same outcomes for patients with CD, who received anti-TNF therapy early [n = 247] vs late [n = 495] after diagnosis. In this group, early anti-TNF initiation was associated with significantly lower rates of hospitalization or resective surgery up to 5 years after treatment initiation.

3.3. Long-term outcomes [follow-up of more than 5 years]

Focht et al. examined data on Epi-IIRN cohort diagnosed IBD patients between 2005 and 2020.31 The authors examined a slightly different question on whether there are differences with respect to outcomes such as 10-year colectomy and corticosteroid dependency to be observed between different early initiation treatment periods with biologics. Of the 34 375 patients [98% of the Israeli patients], 2235 UC patients received biologics. Of these, 206, 450, 396, and 271 received biologics within 0–3 months, 3–12 month, 1–2 years, and 2–3 years of the disease diagnosis, respectively. Whilst no difference in 10-year colectomy rates were observed (survival probabilities of 0.92 [95% CI 0.87–0.97] for 0–3 months vs 0.94 [95% CI 0.91–0.98] for 2–3 years, p = 0.42), there was a difference in corticosteroid-dependency rates between the groups receiving biologics within 0–3 months and 2–3 years (survival probabilities of 0.78 [95% CI 0.75–0.82] and 2–3 years [0.69 [95% CI 0.66–0.71], p < 0.001) of the disease diagnosis. When CD patient data were examined, a modest decrease in CD-related surgery was observed (survival probabilities of 0.75 [95% CI 0.71–0.79] for 0–3 months vs 0.7 [95% CI 0.66–0.73] for 2–3 years, p < 0.05), and more apparent decrease in corticosteroid dependency (survival probabilities 0.78 [95% CI 0.75–0.82] 0–3 months vs 0.69 [95% CI 0.66–0.71] for 2–3 years, p < 0.001).

4. Why May Early Escalation of Biological Agents Lack Benefit in UC?

Recognizing the limitations of the existing data, there currently appears to be minimal evidence that patients with UC benefit from early escalation to advanced therapies, in contrast to data from CD, although high-quality evidence to support early use of advance therapies in CD remains limited. Whilst some of the hypothesized reasons for this difference are outlined below, the studies enrolling high numbers of patients with long follow-up periods are required. Further subanalyses of UC patient populations with different activity and course of their disease as well as relatively long disease duration are needed to identify those patients who might benefit from early escalation in UC.

First, in CD poorly controlled, long-standing, transmural inflammation is thought to be one of the leading drivers of intestinal fibrosis and penetrating complications accruing over time, which is associated with an increased need for surgery, morbidity, and possibly mortality.5,32 Therefore, it is likely that the benefits from biologics in CD are thought to derive from their ability to slow down or mitigate these changes through early control of the inflammatory disease burden.33 Intervening with advance therapies during earlier rather than later stages of disease potentially not only leads to mucosal healing, but also reduces the risk of stricturing complications, hospitalizations, and surgery.34–36 The question of whether adoption of the early escalation strategy in UC is equally as effective as in CD is less clear. The findings by Ben-Horin and colleagues that treatment-related response and spontaneous remissions do not decrease over time in UC further support the argument against the concept of an early ‘window of opportunity’ for the general UC population.22 Given that in a study by Focht et al. the use of anti-TNF within the first 3 months of disease diagnosis was associated with an increased likelihood of being in corticosteroid-free remission, very early use of advanced therapies should be further examined.31 However, it should be recognized that, clearly, some patients do present with severely active or even fulminant disease activity that does require aggressive treatment. This is reflected in the fact that most patients who do require colectomy will undergo this intervention within the first 2 years after diagnosis.5,37,38 For other patients with a relapsing and remitting disease course, a data-driven definition for the optimal timing of treatment initiation is currently lacking, but it is generally dictated by emergence of moderate-to-severe disease activity, defined by clinical, endoscopic, or biomarker activity.

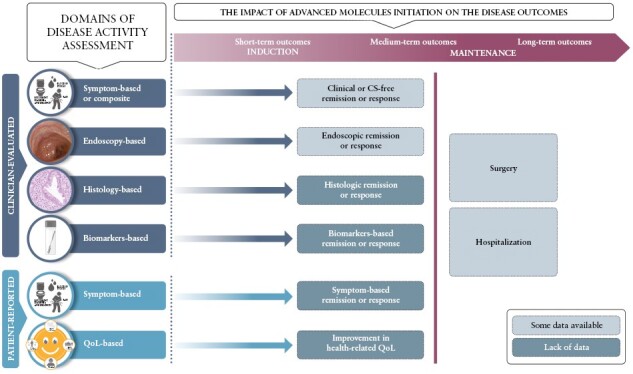

Second, defining the benefits of early advanced therapy introduction in UC has also proved challenging. The endpoint of colectomy in UC patients occurs less frequently when compared to CD, and therefore may be inadequately sensitive for use as a measure of changing the natural history of disease in studies evaluating the benefit of early advanced treatment initiation. Potentially a longer duration of follow-up may be necessary to demonstrate long-term benefits of early anti-TNF use with respect to that outcome than the currently available 3–5 years of follow-up, especially since diagnostic delay associated with UC is shorter than with CD.29,39,40 The benefit of early advanced treatment initiation on other potentially relevant outcomes should also be considered [Figure 2], including patient-reported outcomes [PROs] and avoidance of corticosteroids. PROs are becoming increasingly central for measuring treatment effects relevant to patients. Symptom-based PROs are underused in clinical trials and observational studies in UC patients.41 Faecal urgency, and associated increased stool frequency, may be related not only to ongoing inflammation but also to submucosal fibrosis.42 This fibrosis may explain the presence of urgency in endoscopically quiescent UC and discordant findings between improvement in stool frequency and endoscopic findings.43 Therefore, prevention or potentially reversing this fibrosis with early intervention may be an important therapeutic target in the future. Whilst no relationship between disease duration and clinical remission rates was found by Ben-Horin and colleagues, it may well be that early treatment with advanced therapies may impact other PRO endpoints, such as long-term health-related quality of life.22

Figure 2.

Gap analysis of endpoints analysed for the purposes of early escalation studies.

Third, treatment escalation in CD may be driven by a paucity of highly effective and safe therapeutic options for patients with mild-to-moderate, as opposed to moderate-to-severe, CD. Corticosteroids, thiopurines, and methotrexate have some evidence to support their efficacy as either induction or maintenance therapies, but these treatments are associated with important toxicity profiles, whereas 5-ASA formulations show very limited or no benefit in CD.44 The limited armamentarium of treatment options in CD in the space typically occupied by 5-ASA formulations in UC often prompts an earlier switch to advanced agents.

It is also likely that the above-mentioned studies are not entirely comparable. The UC patients included within RCTs differ from those included in real-word evidence studies with respect to important disease characteristics, including disease activity, severity, and duration. Previous work has suggested that only approximately one in three patients seen as part of routine care would be eligible for RCTs.45 The Mayo Clinic Score [MCS] or 9-point modification of the MCS is currently used to define both eligibility and outcomes: all available biologic and small molecule therapies have received regulatory approval on the basis of the MCS. However, it is important to note that the 9-point MCS is an evaluative instrument for disease activity, reflecting stool frequency, rectal bleeding, and endoscopic appearance. RCTs have not stratified or restricted eligibility on the basis of disease severity: this is a separate concept that also considers risk of disease progression and natural history. Therefore, while the current data do not support early introduction of advanced therapies in UC, additional work is required to validate instruments to differentiate severe from mild and moderate UC and understand treatment strategies that may change the natural history in this sub-population. The above-mentioned real-world studies also differed with respect to the outcomes selected, which complicates the comparison between studies. In general, this heterogeneity in use of outcomes and defining disease activity in RCTs, real-world evidence studies, and clinical practice in UC poses challenges not only for comparative research, but also for the way treatments are applied in clinical practice.8,43,46 For example, a recent systematic review of RCTs identified six different scores used for classifying mildly-to-moderately active UC.47 There is still no consensus on score cut-offs based on which disease severity is defined.48 It is likely that as a result of this heterogeneity, ECCO treatment guidelines do not explicitly define mildly-to-moderately and moderately-to-severely active UC.8 This, in turn, means that the criteria for applying treatments are also probably heterogeneous.

5. What is the Risk from Early use of Advanced Therapies?

Whilst 5-ASAs have favourable safety profiles, even at maximum doses, suboptimal optimization of dosage and administration of this first-line therapy is common in UC patients; based on recently conducted modelling, a 39% increase in patients achieving remission and 21% reduction in relapses were observed through 5-ASA optimization.49 Compared with broad-spectrum second-line immunosuppressive agents, such as corticosteroids and thiopurines, most of the biologics and small molecules also have a favourable safety profile. Nevertheless, the chronic use of these medications is associated with the potential for side effects, of which risks of infections, malignancies, and cardiovascular events are of particular concern depending on the class.

The use of anti-TNF agents is associated with a risk of opportunistic infections, including herpes zoster, and melanoma as well as paradoxical reactions such as psoriasiform reactions.50,51 Among patients with IBD treated with TNF inhibitors, frail individuals have been found to have an increased rate of severe infections when compared with fit patients.52 Whilst we have a substantial body of evidence on the safety of anti-TNF, data on the safety of more recently approved advanced therapies are limited. In a recent systematic review and network meta-analysis of UC trials, Lasa and colleagues have found that although no differences between advanced therapies were observed with respect to adverse events and serious adverse events, they observed a trend towards a higher efficacy and a less favourable safety profile.20 Specifically, the anti-integrin vedolizumab, which acts specifically in the gut and has no effect on T lymphocytes in the central nervous system, ranked lowest for both adverse events and serious adverse events, whilst upadacitinib and the sphingosine 1-phosphate modulator, ozanimod, ranked highest for adverse events and serious adverse events, respectively. In a meta-analysis of RCTs for all the indications of ozanimod examined, its use has been shown to be associated with a greater risk of herpes zoster infection, transient bradycardia, and atrio-ventricular block.53

Risks associated with JAK inhibition as a class have recently garnered substantial attention. The ORAL Surveillance trial was the United States Food and Drug Administration [US FDA]-mandated post-marketing open-label trial in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, examining the safety of tofacitinib compared to anti-TNF therapy. This was an event-based trial, enriched with patients at high risk for adverse events [eligible participants were ≥50 years, with at least one established cardiovascular risk factor], and powered for detecting non-inferiority of the co-primary endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events [MACEs] and malignancy [excluding non-melanoma skin cancer]. Over 4000 patients participated in this study, followed for a median duration of 4 years.54 There was a higher incidence of MACEs and malignancy, opportunistic and herpes zoster infections, venous thromboembolism, and non-melanoma skin cancer in patients receiving tofacitinib, which did not demonstrate non-inferiority compared to anti-TNF. However, there was effect modification both by age and smoking status for many of the important endpoints. These data, as well safety data generated from other JAK inhibitors across immune-mediated diseases, have undergone extensive review at multiple regulatory authorities around the world, including the US FDA and European Medicines Agency [EMA]. It is controversial whether these data are directly applicable to patients with UC, who are generally younger and less comorbid compared to the high-risk population enrolled in ORAL Surveillance. Whereas the US FDA has relegated JAK inhibitors to second-line therapy after anti-TNF failure, the EMA and multiple other regulatory agencies have not adopted similar positions on treatment sequencing, although the EMA did issue a warning that the use of tofacitinib and other JAK inhibitors should be considered an option of last resort in ‘those aged 65 years or above, those at increased risk of major cardiovascular problems [such as heart attack or stroke], those who smoke or have done so for a long time in the past and those at increased risk of cancer’.55 European regulators also advised ‘caution in patients with risk factors for blood clots in the lungs and in deep veins [venous thromboembolism, VTE]’. The use of tofacitinib is also associated with an increased risk of opportunistic infections [including herpes zoster and tuberculosis], all herpes zoster [non-serious and serious], and non-melanoma skin cancer.55 The increased risk of opportunistic infections and herpes zoster is class-specific and has been observed for drugs such as upadacitinib and filgotinib as well.56

Whilst physicians have gained considerable comfort using established biologics such as anti-TNFs, the risk factors or consideration for comorbidities associated with the use of these relatively new medications add an important degree of complexity to treatment decisions in patients with UC.

6. Identifying Appropriate UC Patients for Early Escalation

Appropriate escalation of therapy in UC is an important landmark in a patient’s disease course. This is a balance between allowing some degree of long-standing inflammation that may be associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer with treating more aggressively in the hope of stringently controlling inflammation but exposing patients to potential risks of treatment-emergent adverse events. Although physicians previously were concerned about the limited scope of therapies available for escalation in patients who may be adequately but not perfectly controlled with conventional therapies, the ever-increasing armamentarium of advanced therapies being developed lessens these concerns and, among others, paves the way for escalation earlier rather than later in the disease course. Whilst the field of IBD has stepped away from symptom control as the only treatment target to a more stringent target of tissue healing on the level of endoscopy, histology, and barrier function, deep mucosal healing remains an elusive target in many UC patients.57 For example, there is an increasing body of evidence that suggests that achieving histological remission [traditionally defined by resolution of neutrophilic inflammation] in UC patients is associated with a reduced risk of clinical relapse, corticosteroid use, hospitalization, and colectomy compared with achieving clinical remission or even endoscopic remission alone.58–60 In systematic reviews of pharmacological therapies in RCTs for UC, histological remission is achieved in ~60% of patients treated with 5-ASA.61 Although the association between histology and long-term outcomes has been observed, it is currently unclear whether prospectively escalating treatment to achieving a histological target improves outcomes, particularly in patients already in clinical or endoscopic remission. The ongoing VERDICT treat-to-target trial will hopefully provide clarity on the additive benefit of treating to histological remission [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04259138].62 In conclusion, these stringent treatment targets are not only difficult to achieve, but current evidence supporting this as the treatment target in UC remains associational; therefore, achieving these targets rests on a balancing act: physicians strive for gain in effectiveness, but also need to consider potentially a greater number of adverse events and increasing costs.63

Aiming for stringent inflammation control comes with an increase in the cost of therapy. Recent modelling based on UK pricing levels showed that on average £272 per patient could be saved for induction and maintenance of remission over 1 year following 5-ASA treatment optimization that avoids the costs associated with the use of anti-TNF and induction-phase systemic corticosteroids.64 However, those costs probably differ across healthcare settings. It is likely that in the USA, these savings would be substantial, as the recently estimated costs of achieving remission were calculated to be $249 417, $267 463, $365 050, $579 622, $750 200, and $787 998 for tofacitinib 5 mg, infliximab, vedolizumab, golimumab, adalimumab, and ustekinumab, respectively.65 In the USA, the yearly cost of 5-ASA medications is less than $10 000.66 Whilst data on the recent costs of achieving remission incorporating the number needed to treat are lacking, in the period between 2006 and 2008 the cost of preventing a flare was estimated at $8810 per flare.67

Identifying the UC patient population that may well benefit from early escalation of therapy is a subject of great interest that is typically centred around negative prognostic markers, such as predictors of severe or complicated disease course. Whilst patients of young age at first diagnosis, or those with extensive disease, and high inflammatory burden, have been identified as those who might benefit from treatment escalation earlier rather than later in the course of their disease, there are no RCT data to indicate that early use of advanced molecules in these types of patients improves their outcomes. Whilst physicians recognize that some patients with mildly-to-moderately active UC may require up to a few courses of corticosteroids before continuing with 5-ASA maintenance therapy, data on a number of flares/courses per year that would be acceptable before switching to advanced therapies are currently lacking, especially relative to the timing of diagnosis. As we have already discussed, 30% of patients with long-term ‘relapsing & remitting’ UC activity might benefit from escalation to advanced therapies earlier rather than later in a disease course, but it is likely that without stratification, the data on outcomes in this population are masked by the other 70% with a more quiescent disease course after an initial period of flares.

In general, the decisions around surgery are highly variable and depend, among others, on the healthcare setting, as regional differences in colectomy rates between Northern and Southern Europe, and Northern and Eastern Europe have been observed.38,68 Whilst it could be hypothesized that limited access to biologics in centres in Eastern Europe would translate into increased surgery rates, the colectomy rates were lower than in Western Europe. Although we might be seeing a more aggressive natural disease course in terms of disease extent and increasing use of advanced therapies over time, the colectomy rates remained either relatively steady or decreased slightly over the past two decades, perhaps due to a decrease in elective surgery rates at least in some countries.69,70 Therefore, based on the results of population-based studies it appears that the use of advanced therapies, again mostly anti-TNF, is not associated with a direct reduction in colectomy rates. However, these therapies may have an effect on disease severity or other relevant outcomes, such as number of flares, rates of corticosteroid-free remission, or cumulative health-related quality of life.

7. Conclusions

Unlike in CD, the utility of the concept of early escalation for the purposes of improving patient outcomes is not supported by the available data in UC. Current data from systematic reviews and individual-patient data meta-analysis of RCTs as well as retrospective studies in real-life populations point against a concept of a ‘window of opportunity’ for escalation of treatments in UC.

Moreover, data on patient-centred outcomes beyond colectomy or hospitalizations, such as PROs and health-related QoL, as well as analyses of different populations of UC patients, such as those with ‘relapsing & remitting’ disease or with severe or complicated disease course, are urgently needed. To identify predictors of response to various therapies, state-of-the-art multi-omic approaches should be widely implemented. In patients with mild and moderate disease, the optimization of available non-biological therapies remains an important strategy. The risk/benefit profile of some of the newer advanced therapies should be carefully considered.

In such a clinical landscape, it appears premature to advocate an indiscriminate ‘one size fits all’ approach to escalating to advanced therapies early during the course of UC.

Contributor Information

Johan Burisch, Gastro Unit, Medical Division, Copenhagen University Hospital – Amager and Hvidovre, Hvidovre, Denmark; Copenhagen Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children, Adolescents and Adults, Copenhagen University Hospital – Amager and Hvidovre, Hvidovre, Denmark.

Ekaterina Safroneeva, Tillotts Pharma AG, Rheinfelden, Switzerland; Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Raphael Laoun, Tillotts Pharma AG, Rheinfelden, Switzerland.

Christopher Ma, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada; Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada.

Funding

This work was supported by Tillotts Pharma AG.

Conflict of Interest

JB reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, grants and personal fees from Janssen-Cilag, personal fees from Celgene, grants and personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from Takeda, grants and personal fees from Tillots Pharma, personal fees from Samsung Bioepis, grants and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, grants from Novo Nordisk, personal fees from Pharmacosmos, personal fees from Ferring, and personal fees from Galapagos, outside the submitted work. ES and RL are employees of Tillotts Pharma AG. CM has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Alimentiv, Amgen, AVIR Pharma Inc., BioJAMP, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Janssen, McKesson, Mylan, Pendopharm, Pfizer, Prometheus Biosciences Inc., Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda; speaker’s fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AVIR Pharma Inc., Alimentiv, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Janssen, Organon, Pendopharm, Pfizer, and Takeda; royalties from Springer Publishing; and research support from Ferring and Pfizer.

Author Contributions

CM, ES, RL, JB: study concept and design; drafting of the manuscript. Guarantor of the article: JB. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

There are no new data associated with this article

References

- 1. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017;390:2769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gargallo Puyuelo CJ, Ricart E, et al. P0258 Phenotypic differences in inflammatory bowel disease between women and men: SEXEII study of ENEIDA, United European Gastroenterology Journal. 2022;10:473-1092. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Høie O, et al. The clinical course of Crohn’s disease in a Danish population-based inception cohort with more than 50 years of follow-up, 1962-2017. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:1430–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burisch J, Lophaven S, Langholz E, Munkholm P.. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2022;55:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wewer MD, Langholz E, Munkholm P, et al. Disease activity patterns of inflammatory bowel disease—A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study 1995–2018. J Crohns Colitis 2023;17:329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Targownik LE, Bernstein CN, Benchimol EI, et al. Earlier anti-TNF initiation leads to long-term lower health care utilization in Crohn’s disease but not in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20:2607-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. ; International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021;160:1570–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis 2022;16:2–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, Sauer BG, Long MD.. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:384–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berg DR, Colombel JF, Ungaro R.. The role of early biologic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:1896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams DM. Clinical pharmacology of corticosteroids. Respir Care 2018;63:655–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murray A, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, et al. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;8:CD000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murray A, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK.. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;8:CD000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jairath V, Hokkanen S, Guizzetti L, et al. 5-ASA prescription trends over time in inflammatory bowel disease 1996 to 2015–A UK population-based study. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:S309–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15. McKeage K, Goa KL, Goa KL.. Budesonide (Entocort EC Capsules): a review of its therapeutic use in the management of active Crohn’s disease in adults. Drugs 2002;62:2263–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rice JB, White AG, Scarpati LM, Wan G, Nelson WW.. Long-term systemic corticosteroid exposure: a systematic literature review. Clin Ther 2017;39:2216–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sherlock ME, MacDonald JK, Griffiths AM, Steinhart AH, Seow CH.. Oral budesonide for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD007698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chhibba T, Ma C.. Is there room for immunomodulators in ulcerative colitis? Expert Opin Biol Ther 2020;20:379–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Safroneeva E, Vavricka SR, Fournier N, Straumann A, Rogler G, Schoepfer AM.. Prevalence and risk factors for therapy escalation in ulcerative colitis in the Swiss IBD cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:1348–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lasa JS, Olivera PA, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L.. Efficacy and safety of biologics and small molecule drugs for patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Billioud V, D’Haens G, et al. Development of the Paris definition of early Crohn’s disease for disease-modification trials: results of an international expert opinion process. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1770–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ben-Horin S, Novack L, Mao R, et al. Efficacy of biologic drugs in short-duration versus long-duration inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and an individual-patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterology 2022;162:482–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ma C, Beilman CL, Huang VW, et al. Similar clinical and surgical outcomes achieved with early compared to late anti-TNF induction in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;2016:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mandel MD, Balint A, Golovics PA, et al. Decreasing trends in hospitalizations during anti-TNF therapy are associated with time to anti-TNF therapy: results from two referral centres. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46:985–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nuij VJAA, Zelinkova Z, Rijk MCM, et al. ; Dutch Delta IBD Group. Phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease at diagnosis in the Netherlands: a population-based inception cohort study (the Delta Cohort). Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:2215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nuij V, Fuhler GM, Edel AJ, et al. ; Dutch Delta IBD Group. Benefit of earlier anti-TNF treatment on IBD disease complications? J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dulai PS, Singh S, Jiang X, et al. The real-world effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab for moderate-severe Crohn’s disease: results from the US Victory consortium. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Faleck DM, Winters A, Chablaney S, et al. Shorter disease duration is associated with higher rates of response to vedolizumab in patients with Crohn’s disease but not ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:2497–2505.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Han M, Jung YS, Cheon JH, Park S.. Similar clinical outcomes of early and late anti-TNF initiation for ulcerative colitis: a nationwide population-based study. Yonsei Med J 2020;61:382–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Targownik LE, Bernstein CN, Benchimol EI, et al. Earlier anti-TNF initiation leads to long-term lower health care utilization in Crohn’s disease but not in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022:S1542356522001471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Focht G, Lugan R, Atia O, et al. Does early initiation of biologics change the natural history of IBD? A nationwide study from the epi-IIRN. J Crohns Colitis 2023;17:i17–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burisch J, Kiudelis G, Kupcinskas L, et al. ; Epi-IBD group. Natural disease course of Crohn’s disease during the first 5 years after diagnosis in a European population-based inception cohort: an Epi-IBD study. Gut 2019;68:423–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma C, Beilman CL, Huang VW, et al. Anti-TNF therapy within 2 years of crohn’s disease diagnosis improves patient outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:870–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. D’Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, et al. ; Belgian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Group. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet 2008;371:660–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Safroneeva E, Vavricka SR, Fournier N, et al. ; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. Impact of the early use of immunomodulators or TNF antagonists on bowel damage and surgery in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:977–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ungaro RC, Yzet C, Peter Bossuyt P, et al. Deep remission at 1 year prevents progression of early Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2020;159:139–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kirchgesner J, Lemaitre M, Rudnichi A, et al. Therapeutic management of inflammatory bowel disease in real-life practice in the current era of anti-TNF agents: analysis of the French administrative health databases 2009-2014. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Burisch J, Katsanos KH, Christodoulou DK, et al. ; Epi-IBD Group. Natural disease course of ulcerative colitis during the first five years of follow-up in a European population-based inception cohort-an Epi-IBD study. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Olén O, Askling J, Sachs MC, et al. Mortality in adult-onset and elderly-onset IBD: a nationwide register-based cohort study 1964–2014. Gut 2020;69:453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vavricka SR, Spigaglia SM, Rogler G, et al. ; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ma C, Panaccione R, Fedorak RN, et al. Heterogeneity in definitions of endpoints for clinical trials of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review for development of a core outcome set. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:637–647.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dubinsky MC, Irving PM, Panaccione R, et al. Incorporating patient experience into drug development for ulcerative colitis: development of the Urgency Numeric Rating Scale, a patient-reported outcome measure to assess bowel urgency in adults. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2022;6:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ma C, Jeyarajah J, Guizzetti L, et al. Modeling endoscopic improvement after induction treatment with mesalamine in patients with mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20:447–454.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14:4–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ha C, Ullman TA, Siegel CA, Kornbluth A.. Patients enrolled in randomized controlled trials do not represent the inflammatory bowel disease patient population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:1002–7; quiz e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wong C, van Oostrom J, Bossyut P, et al. A narrative systematic review and categorisation of outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease to inform a core outcome set for real-world evidence. J Crohns Colitis 2022;6:1511–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Caron B, Jairath V, D’Amico F, et al. Definition of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis in clinical trials: A systematic literature review. United European Gastroenterol J 2022;10:854–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sedano R, Jairath V, Ma C; IBD Trial Design Group. Design of clinical trials for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2022;162:1005–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Louis E, Paridaens K, Al Awadhi S, et al. Modelling the benefits of an optimised treatment strategy for 5-ASA in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2022;9:e000853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ford AC, Peyrin-Biroulet L.. Opportunistic infections with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1268–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bataille P, Layese R, Claudepierre P, et al. ; AP-HP/Universities/Inserm COVID-19 research collaboration and on behalf of the ‘Entrepôt de Données de Santé’ AP-HP consortium. Paradoxical reactions and biologic agents: a French cohort study of 9303 patients. Br J Dermatol 2022;187:676–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kochar B, Cai W, Andrew Cagan A, Ananthakrishnan AN.. Pretreatment frailty is independently associated with increased risk of infections after immunosuppression in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2020;158:2104–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lasa JS, Olivera PA, Bonovas S, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L.. Safety of S1p. modulators in patients with immune-mediated diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf 2021;44:645–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. New Engl J Med 2022;386:316–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-recommends-measures-minimise-risk-serious-side-effects-janus-kinase-inhibitors-chronic. Last accessed May 13, 2023.

- 56. Clarke B, Yates M, Adas M, Bechman K, Galloway J.. The safety of JAK-1 inhibitors. Rheumatology [Oxford] 2021;60:ii24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Alipour O, Gualti A, Shao L, Zhang B.. Systematic review and meta-analysis: real-world data rates of deep remission with anti-TNFα in inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol 2021;21:312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ma C, Sedano R, Almradi A, et al. An international consensus to standardize integration of histopathology in ulcerative colitis clinical trials. Gastroenterology 2021;160:2291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Park S, Abdi T, Gentry M, Laine L.. Histological disease activity as a predictor of clinical relapse among patients with ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC. Histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up. Gut 2016;65:408–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Battat R, Duijvestein M, Guizzetti L, et al. Histologic healing rates of medical therapies for ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:733–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. clinicaltrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04259138. Last accessed on May 13, 2023.

- 63. Yoon H, Jangi S, Dulai PS, et al. Incremental benefit of achieving endoscopic and histologic remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2020;159:1262–1275.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Louis E, Paridaens K, Al Awadhi S, et al. Modelling the benefits of an optimised treatment strategy for 5-ASA in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2022;9:e000853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jairath V, Cohen RD, Loftus EV, Candela N, Lasch K, Schultz BG.. Evaluating cost per remission and cost of serious adverse events of advanced therapies for ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2022;22:501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shaffer SR, Huang E, Patel S, Rubin DT.. Cost-effectiveness of 5-aminosalicylate therapy in combination with biologics or tofacitinib in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116:125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yen EF, Kane SV, Ladabaum U.. Cost-effectiveness of 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:3094–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hoie O, Wolters FL, Riis L, et al. ; European Collaborative Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Low colectomy rates in ulcerative colitis in an unselected European cohort followed for 10 years. Gastroenterology 2007;132:507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wetwittayakhlang P, Gonczi L, Lakatos L, et al. Long-term colectomy rates of ulcerative colitis over 40-year of different therapeutic eras - results from western hungarian population-based inception cohort between 1977 and 2020. J Crohns Colitis 2023:17:712–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Worley G, Almoudaris A, Bassett P, et al. Colectomy rates for ulcerative colitis in England 2003–2016. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021;53:484–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chibbar R, Moss AC.. Mesalamine in the initial therapy of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2020;49:689–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no new data associated with this article