Abstract

Background

The role of copper accumulation in the onset of hepatitis is still unclear. Therefore, we investigated a spontaneous disease model of primary copper-toxicosis in Doberman pinschers so to gain insights into the pathophysiology of copper toxicosis, namely on genes involved in copper metabolism and reactive oxygen species (ROS) defences.

Results

We used quantitative real-time PCR to determine differentially expressed genes within a target panel, investigating different groups ranging from copper-associated subclinical hepatitis (CASH) to a clinical chronic hepatitis with high hepatic copper concentrations (Doberman hepatitis, DH). Furthermore, a non-copper associated subclinical hepatitis group (N-CASH) with normal hepatic copper concentrations was added as a control. Most mRNA levels of proteins involved in copper binding, transport, and excretion were around control values in the N-CASH and CASH group. In contrast, many of these (including ATP7A, ATP7B, ceruloplasmin, and metallothionein) were significantly reduced in the DH group. Measurements on defences against oxidative stress showed a decrease in gene-expression of superoxide dismutase 1 and catalase in both groups with high copper. Moreover, the anti-oxidative glutathione molecule was clearly reduced in the DH group.

Conclusion

In the DH group the expression of gene products involved in copper efflux was significantly reduced, which might explain the high hepatic copper levels in this disease. ROS defences were most likely impaired in the CASH and DH group. Overall, this study describes a new variant of primary copper toxicosis and could provide a molecular basis for equating future treatments in dog and in man.

Background

Copper is an imperative molecule in life; in contradiction, however, it is highly toxic [1]. Like zinc, iron, and selenium, copper is an essential trace element in diets and is required for the activity of a number of physiologically important enzymes [2]. Cells have highly specialized and complex systems for maintaining intracellular copper concentrations [3]. If this balance is disturbed, excess copper can induce oxidative stress that could lead to chronic inflammation [4,5]. Copper induced hepatitis has been described both in humans (Wilson's disease) as well as in dogs. There are several non-human models of copper toxicosis models, such as the Long-Evans Cinnamon rats and Bedlington terriers. Although the gene underlying Wilson's disease (ATP7B) is deficient in Long-Evans Cinnamon rats [6-9], in Bedlington terriers it has been excluded as a candidate for copper toxicosis [10]. The recent discovery of mutations in gene MURR1, responsible for copper toxicosis in Bedlington terriers, has given rise to the discovery of a new copper pathway [11]. Here, we describe in Doberman pinschers a copper associated chronic hepatitis (also called Doberman hepatitis), characterized by micro-nodular cirrhosis with elevated hepatic copper concentrations [12-15]. Doberman hepatitis accounts for 4 % of all deaths in a Dutch population of 340 Dobermans [16]. Until recently, the role of copper in the development and progression of hepatitis in the Doberman pinscher had been unclear. Recent studies using intravenous 64Cu clearly show an impaired copper excretion in dogs with hepatitis and elevated copper concentrations [17]. However, genes ATP7B and MURR1 have been excluded by us as possible candidates by genotyping (data not shown). Therefore, Doberman hepatitis can be seen as a separate form of copper toxicosis and a possible model for other types of copper toxicosis in humans, such as Indian childhood cirrhosis, non-Indian childhood cirrhosis, or idiopathic copper toxicosis.

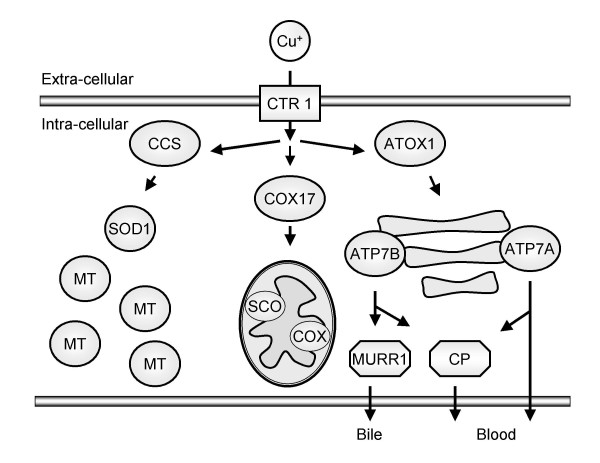

Intracellular copper is always transiently associated with small copper-binding proteins (Figure 1), denoted copper chaperones, which distribute copper to specific intracellular destinations [18]. One of these copper chaperones is the anti-oxidant protein 1 (ATOX1) [19], which transports copper to the copper-transporting ATPases ATP7A and ATP7B [20], located in the trans-Golgi network. Copper can then be bound to liver specific ceruloplasmin (CP) [21] or MURR1 and transferred outside the cell to blood and bile, respectively [22]. The second chaperone – cytochrome c oxidase (COX17) is responsible for delivering copper to the mitochondria for incorporation into cytochrome c oxidase [23]. The third chaperone – copper chaperone for superoxide oxidase (CCS) is responsible for the incorporation of copper into Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) – one of the most important cytosolic enzymes in the defence against oxidative stress [24,25]. Also known as ferroxidase or oxygen oxidoreductase, CP is a plasma metalloprotein which is involved in peroxidation of Fe(II)transferrin to Fe(III)transferrin and forms 90 to 95 % of plasma copper. CP is synthesized in hepatocytes and is secreted into the serum with copper incorporated during biosynthesis. Metallothionein 1A (MT1A) is a small intracellular protein capable of chelating several metal ions, including copper. It contains many cysteine residues, which allow binding and storage of copper. Furthermore, MT1A is inducible, at the transcriptional level, by metals and a variety of stressors such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), hypoxia, and UV radiation [26]. MT1A can donate copper to other proteins, either following degradation in lysosomes or by exchange via glutathione (GSH) complexation [27].

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of intra-cellular copper trafficking in hepatocytes. Copper uptake is mediated by the receptor CTR1. In the cell, copper can bind to copper chaperones such as CCS, COX17, and ATOX1 which in turn deploy to SOD1, the mitochondrial COX, and ATP7A/B, respectively. ATP7A can directly excrete copper or bind it to ceruloplasmin (CP). ATP7B can excrete copper through CP to blood or via MURR1 to bile. Furthermore, metallothioneins (MT) are present in the cytoplasm which can bind and sequester metals. [SCO are metallochaperone proteins with essential, but not yet fully understood, roles in copper delivery to mitochondrial COX.]

High hepatic levels of copper induce oxidative stress. There are several important proteins and molecules involved in the defence against oxidative stress. Most of the anti-oxidants can be grouped into either enzymatic defences or non-enzymatic defences [28]. The enzymatic defence against oxidative stress consists of several proteins that have tight regulations such as SOD1 and catalase (CAT). Non-enzymatic defences against oxidative stress consist of molecules such as α-tocopherol, β-carotene, ascorbate, and a ubiquitous low molecular thiol component – the GSH [29]. The present study was undertaken to investigate the effect of copper toxicosis on expression of gene-products involved in copper metabolism and oxidative stress in several gradations of hepatic copper toxicosis in Doberman pinschers.

Results

To gain insight into the pathogenesis of copper toxicosis, we first measured mRNA levels on several important copper binding gene-products by means of quantitative real-time PCR (Q-PCR). Because copper toxicity is often associated with oxidative stress, we also measured several oxidative stress related gene-products. To determine a possible damaging effect of the oxidative stress, we investigated proteins involved in apoptosis and cell-proliferation.

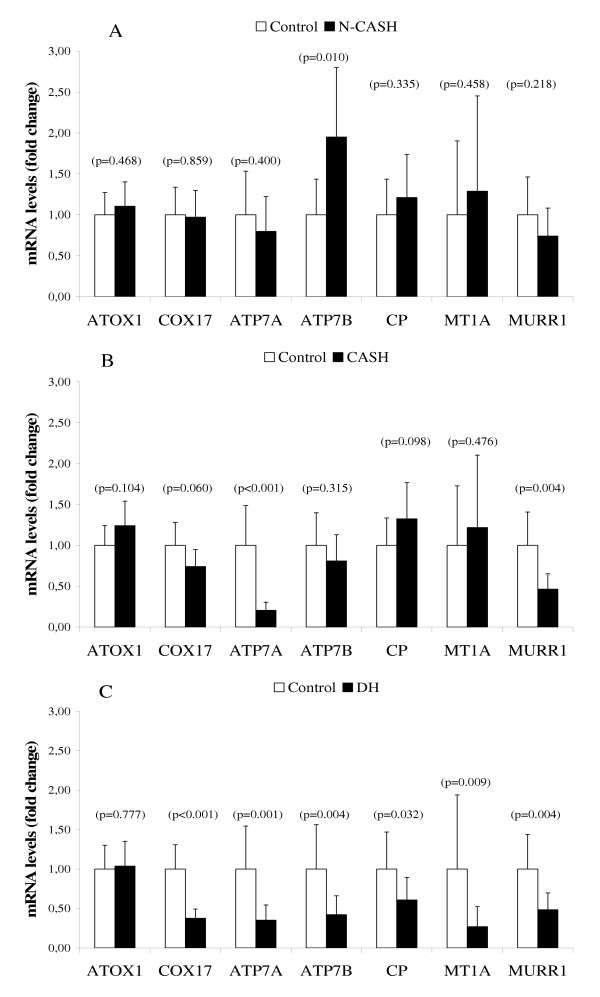

Gene-expression measurements on copper metabolism related gene products

Several proteins in the Doberman hepatitis (DH) group are reduced compared to healthy controls (Figure 2C). In all groups the copper chaperone ATOX1 is not affected, whereas COX17 is decreased three-fold in the DH group and remains unchanged in the non-copper associated subclinical hepatitis group (N-CASH, Figure 2A) and copper associated subclinical hepatitis group (CASH, Figure 2B). In the DH group, the mRNA levels of both trans-Golgi copper transporting proteins ATP7A and ATP7B are decreased, three- and two-fold respectively. Interestingly, mRNA levels of ATP7A are decreased in the CASH group as well (Figure 2B). In contrast, ATP7B is not affected in the CASH group but is induced two-fold in the N-CASH group. CP mRNA levels are normal except for the DH group where it is decreased two-fold. The same observation was made with measurements on MT1A mRNA, although this protein is decreased four-fold in the DH group. The protein MURR1 (that transports copper from hepatocytes into bile) is unaffected in the N-CASH group but halved in the CASH and DH groups.

Figure 2.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR of copper metabolism related genes. mRNA levels of non-copper associated subclinical hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) is shown in (A). mRNA levels of copper associated subclinical hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) is shown in (B). mRNA levels of Doberman hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) is shown in (C). Data represent mean ± 2 SD.

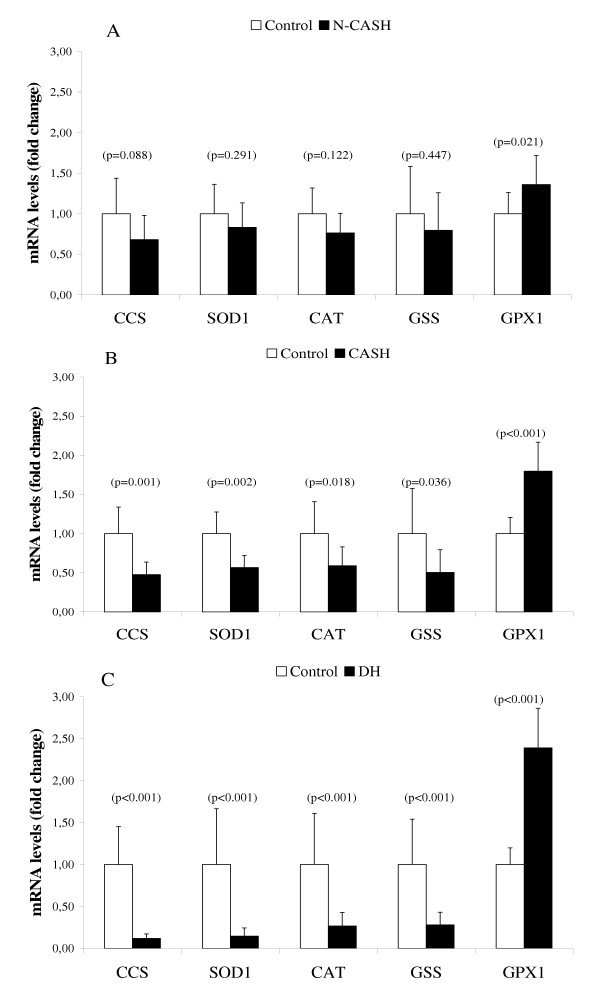

Gene expression measurements on oxidative stress markers

SOD1 and CAT are reduced 7- and 4-fold (respectively) in the DH group when compared to healthy controls (Figure 3C). This reduction in mRNA levels can be seen in the CASH group (Figure 3B), where SOD1 and CAT are halved, but are not lowered significantly in the N-CASH group (Figure 3A). One of the GSH synthesis enzymes – the glutathione synthetase (GSS) is unaffected in the N-CASH group but reduced 2 to 4-fold in the CASH and DH group, respectively. The glutathione peroxidase (GPX1) responsible for converting oxidized glutathione (GSSG) into its reduced form (GSH) is induced slightly in mRNA expression in the N-CASH group, and is doubled in the CASH and DH groups. The third copper chaperone CCS, responsible for the transport of copper to SOD1, is inhibited 8-fold in the DH group, 2-fold in the CASH group, and remained unchanged in the N-CASH group.

Figure 3.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR of oxidative stress markers. mRNA levels of non-copper associated subclinical hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) is shown in (A). mRNA levels of copper associated subclinical hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) is shown in (B). mRNA levels of Doberman hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) is shown in (C). Data represent mean ± 2 SD.

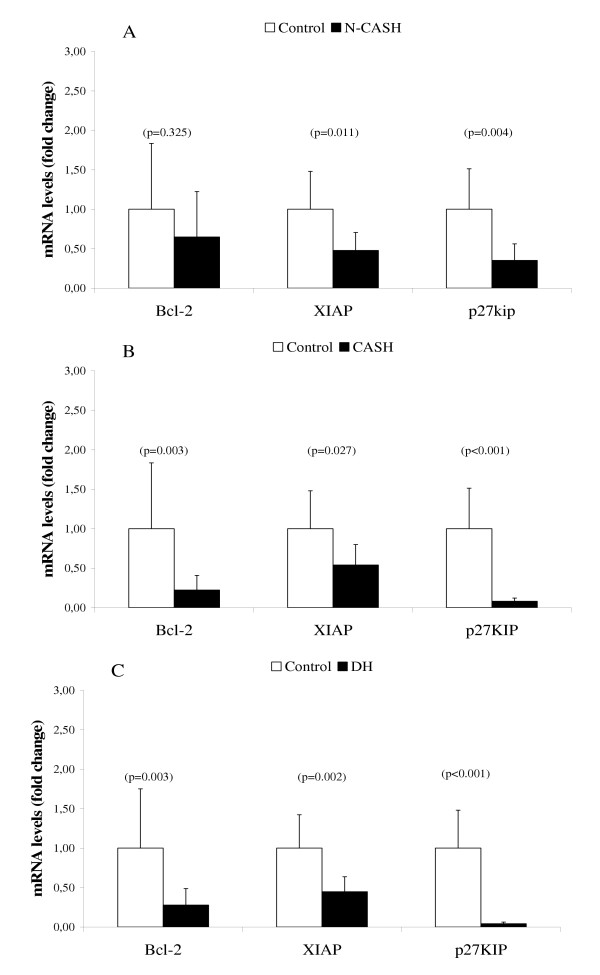

Gene expression measurements on apoptosis and cell proliferation

We measured two anti-apoptotic gene products, viz. Bcl-2, the frequently described anti-apoptotic protein, and a x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) recently associated with MURR1 [30]. Our apoptosis measurements on Bcl-2 showed no reduction in gene expression in the N-CASH group (Figure 4A), but is inhibited 4-fold in the CASH and DH groups (Figures 4B and 4C, respectively). XIAP is halved in all groups. The most dramatic changes were found in the mRNA levels of the cell-cycle inhibitor p27KIP which is inhibited 24-fold in the DH group, 12-fold in the CASH group, and 3-fold in the N-CASH group.

Figure 4.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR of apoptosis and cell proliferation related genes. mRNA levels of non-copper associated subclinical hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) is shown in (A). mRNA levels of copper associated subclinical hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) is shown in (B). mRNA levels of Doberman hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) is shown in (C). Data represent mean ± 2 SD.

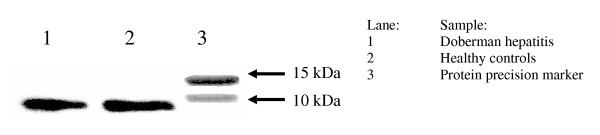

Western blots analysis on metallothionein proteins during copper toxicosis

Measurements on the mRNA levels of MT1A showed a marked decrease in gene expression in the DH group. In order to see whether this decrease was also occurring at the protein level, Western blots were performed in order to confirm decreased mRNA levels. Therefore, the total amount of metallothionein was determined from Doberman pinschers with chronic hepatitis and high copper (DH-group) levels compared to healthy Dobermans. Metallothionein was detected in both samples, where it was present as a single band of 6 kDa (Figure 5). Interestingly, the immunoreactive band shows no difference in concentration between the two samples.

Figure 5.

Western blot analysis of the metallothionein proteins. Immunoreactive bands of total metallothionein of pooled fractions of the Doberman hepatitis (DH) group (n = 6 dogs) versus healthy controls (n = 8 dogs).

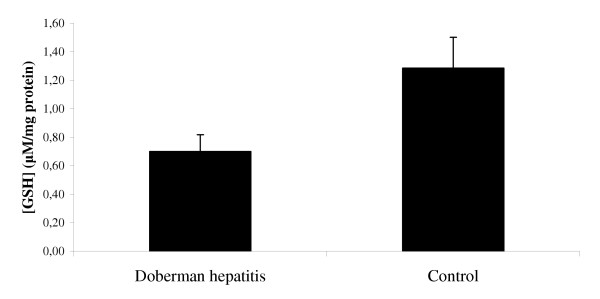

Total Glutathione measurements during copper toxicosis

In order to determine whether the decrease in mRNA levels of GSS decreases the GSH levels, we measured the total amount of GSH. Interestingly, in Figure 6, the total amount of GSH in the high copper group is halved when compared to healthy controls.

Figure 6.

Total glutathione (GSH) measurements during copper toxicosis in Doberman. Total GSH levels of pooled protein fractions of the Doberman hepatitis (DH) group (n = 6 dogs) versus healthy controls (n = 8 dogs). Data represent mean ± 2 SD.

Discussion

In the present study, the expression of a total of 15 gene products involved in copper metabolism of Doberman pinschers was measured. This provided insight into the molecular pathways of a canine copper-associated hepatic disease model ranging from subclinical hepatitis with elevated copper levels (CASH) to severe chronic hepatitis with high hepatic copper levels (DH). Furthermore, these diseases were compared to non-copper associated subclinical hepatitis (N-CASH).

Because of the centrolobular accumulation of copper in the hepatocytes during copper toxicosis in the Doberman, a probable defect may be sought in the copper metabolism instead of a secondary effect due to, for instance, cholestasis. Recent findings by Mandigers et al. [17] indicated that Doberman pinschers with hepatitis and elevated copper concentrations suffer from impaired 64Cu bile excretion which is, together with other studies, conclusive that copper toxicosis exists in the Doberman pinscher. Furthermore, a double blind placebo-controlled study with the copper chelating agent, D-penicillamine, on Doberman pinschers with CASH showed a marked improvement of liver pathology [31]; currently, that agent is the only treatment option.

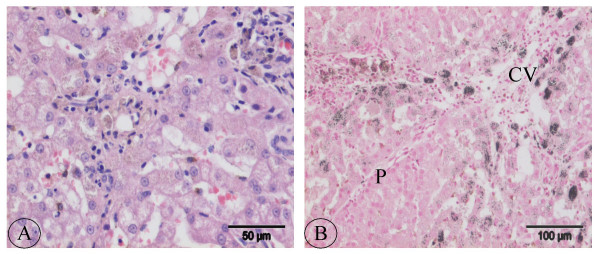

If copper is sequestered, in time metallothioneins will store the copper in lysosomes, as described by Klein et al. [32]. They found that chronic copper toxicity in Long-Evans Cinnamon rats involved the uptake of copper-loaded metallothioneins into lysosomes, where it was incompletely degraded and polymerized into an insoluble material, which contained reactive copper. This copper initiated a lysosomal lipid peroxidation, which led to hepatocyte necrosis. Phagocytosis of this reactive copper by Kupffer cells amplified the liver damage. Histological examination of the DH (Figure 7) and CASH group samples revealed copper accumulation in hepatocytes and copper-laden Kupffer cells similar to that described by Klein et al. [32]; therefore, that can be denoted as benchmarks of chronic exposure to copper.

Figure 7.

Histological evaluation of Doberman hepatitis. (A) Hepatitis characterised by accumulation of pigmented granules (probably copper) in hepatocytes, and inflammation with lymphocytes and pigmented (probably copper) macrophages. HE staining. (B) Centrolobular accumulation of copper in hepatocytes and band of fibrous tissue with inflammatory cells and copper-laden macrophages. Rubeanic acid staining. P = Portal area, CV = Central vein area.

In our study, the gene expression levels of several gene products involved in copper metabolism seem to be reduced in the DH and CASH groups when compared to healthy controls. Short term studies on in vitro models all show an induction of MT1A or CP indicative of a higher efflux of copper from hepatocytes [33,34]. The reductions that are seen in our results could therefore be ascribed to the prolonged or chronic nature of copper accumulation as dogs in the high copper or DH group present clinical signs after 2 years. Therefore, our observations are not directly comparable with the short-term induced copper effects in vitro, but are clinically more relevant, showing the effects of long-term copper accumulation in Doberman hepatitis. However, Western blot experiments on metallothionein, which stores the copper in lysosomes, did not show any reduction at the protein level. This observation could be ascribed to the antibody that binds all metallothioneins, including metallothionein 2 (MT2A), which also is present in the liver. It remains to be proven if this effect is a compensation for the decrease of MT1A.

In the earlier stages of copper accumulation, comparable to the CASH group, higher amounts of copper can still be excreted. Interestingly, in the N-CASH group, ATP7B is indeed induced compared to healthy controls, emphasizing a possible higher efflux of copper. Furthermore, from the two subclinical disease groups, the N-CASH group is the only one able to recuperate, whereas the CASH group will eventually turn into clinical hepatitis as seen in the DH group (data not shown). Taken together, our data suggest that in the Doberman pinchers copper accumulates in time and, finally, will have its negative effect on copper metabolism and induce oxidative stress.

Oxidative stress has been ascribed to copper toxicosis as one of the most important negative effects [35]. We can confirm this with four different observations: (i) our measurements showed a decrease in mRNA levels of SOD1 and CAT, indicative of a reduction in the enzymatic defence against oxidative stress in all groups with copper accumulation; (ii) a reduction of GSS mRNA levels (glutathione synthesis), indicative for a reduced glutathione level in these groups which is one of the most important non-enzymatic molecules against oxidative stress; (iii) the mRNA levels of GPX1 were significantly increased, indicating an increase in GSH oxidation; (iv) the decrease in GSH was confirmed by measuring total glutathione levels in the DH group towards healthy Doberman pinschers. A similar decrease in expression of anti-oxidant enzymes was observed in ApoE-deficient mice in response to chronic inflammation [36], and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [37]. This indicates that chronic inflammation (copper toxicosis, atherosclerosis, IBD) is associated with reduced protection against enhanced exposure to ROS.

Other effects of high copper can also be seen in the measurements on apoptosis and cell-cycle. Measurements on Bcl-2 and XIAP indicate a decrease of protection against apoptosis; however, the most affected hepatocytes will go into necrosis due to the formation of hydroxyl radicals by the Haber-Weiss reaction, which is catalyzed by copper [38]. A striking observation was made measuring p27KIP which was shown to be reduced up to 24-fold in the DH group. This could indicate an induction of cell-cycle compared to healthy controls. This could be ascribed to the renewal of hepatocytes, thus managing the total amount of copper in time.

Whether differential gene expression is cause-or-consequence of hepatitis is unknown. However, it is conceivable that the reduction in copper processing gene products might explain copper accumulation and the subsequent oxidative stress. Furthermore, recent Q-PCR measurements on non-copper related hepatitis and extra hepatic cholestasis suggest that ATP7A and CP are not down-regulated by inflammation or cholestasis (data not shown). Therefore, we can conclude that the decreased expression of these gene products is a Doberman hepatitis specific effect. Other important copper associated gene products such as COX17, ATP7B, and MT1A are probably down-regulated due to inflammation.

Conclusion

This study is the first to show the effect of prolonged exposure to different copper levels on oxidative stress and copper metabolism in canine livers. Our data supports that: (i) Doberman hepatitis is a new variant of primary copper toxicosis; (ii) there is a clear indication of a reduced copper excretion in the Doberman hepatitis group; (iii) there is a clear correlation between high copper levels and reduced protection against ROS; (iv) this Doberman hepatitis could be a good model to study copper toxicosis and its effects for several human copper storage diseases such as Indian childhood cirrhosis, non-Indian childhood cirrhosis, and idiopathic copper toxicosis, and provide the basis for possible future treatments in dog and even in man.

Methods

Dogs

Doberman pinschers were kept privately as companion animals. The dogs were presented to the Department of Clinical Sciences of Companion Animals, Utrecht University, either for a survey investigating the prevalence of Doberman (chronic) hepatitis, as described by Mandigers et al. [39] or were referred for spontaneously occurring liver disease. All samples were obtained after written consent of the owner. The procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee, as required under Dutch legislation.

Groups

Animals were divided in groups based on histopathological examination and quantitative copper analysis. Each group contained both sexes from four to seven years of age. [A possible gender effect was later excluded by looking at the individual data.] Liver tissue of all Doberman pinschers was obtained using the Menghini aspiration technique [40]. Four biopsies, 2–3 cm in length, were taken with a 14-gauge Menghini needle for histopathological examination and quantitative copper analysis and stored for future quantitative PCR and protein investigations. The quantitative copper analysis was performed using instrumental neutron activation analysis via the determination of 64Cu [41]. Histopathological biopsies were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, routinely dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm thick) were stained with haematoxylin-eosin, van Gieson's stain, reticulin stain (according to Gordon and Sweet), and with rubeanic acid. One experienced board certified veterinary pathologist performed all histological examinations. All diseased groups contained at least six animals that were compared with a group of eight age-matched healthy dogs. Four groups were included in this study (Table 1):

Table 1.

Doberman pinscher group description

| Group | n | Hepatic copper | Copper concentrations (mg/kg dry matter) | Clinical observation |

| Healthy | 8 | Normal | 100 – 200 | No abnormalities |

| N-CASH | 6 | Normal | < 300 | Subclinical hepatitis |

| CASH | 6 | Elevated copper levels | > 600 | Subclinical hepatitis |

| DH | 6 | Highly elevated copper levels | > 1500 | Chronic hepatitis |

1) Healthy group (n = 8 dogs), clinically healthy dogs with normal liver enzymes and bile acids. Histopathology of the liver did not reveal histomorphological lesions. Liver copper concentrations were below 200 mg/kg dry matter.

2) Non-copper associated subclinical hepatitis group (N-CASH, n = 6 dogs), dogs with liver enzymes and bile acids within reference values. Although histological examination showed evidence of a slight hepatitis, hepatic copper concentrations were within normal levels, i.e., below 300 mg/kg dry matter. The dogs were classified as suffering from subclinical hepatitis, which most likely was the result of a different etiological factor, such as infections, deficiencies, other toxins, deficient immune status or immune-mediated mechanism [42].

3) Copper associated subclinical hepatitis group (CASH, n = 6 dogs), dogs with liver enzymes and bile acids within reference values. At histopathology these dogs showed centrolobular copper-laden hepatocytes, on occasions apoptotic hepatocytes associated with copper-laden Kupffer cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells and scattered neutrophils. These lesions were classified as subclinical copper-associated hepatitis [43,44]. Hepatic copper concentrations were in all dogs above 600 mg/kg dry matter.

4) Doberman hepatitis group (DH, n = 6 dogs), dogs with chronic hepatitis and elevated hepatic copper concentrations. All dogs were referred with a clinical presentation of hepatic failure (apathy, anorexia, vomiting, jaundice, and in chronic cases sometimes ascites) and died within 2 months after diagnosis from this disease. Heparinized plasma liver enzymes (alkaline phosphatase and alanine aminotransferase) and fasting bile acids were, at least, three times elevated above normal reference values. Abdominal ultrasound revealed small irregular shaped echo dense liver, as performed with a high definition Ultrasound system – HDI 3000 ATL (Philips) – with a 4–7 MHz broad band Faced-array transducer. Histopathology showed chronic hepatitis (Figure 7A) with histological features of fibrosis / micronodular cirrhosis, etc. These lesions are comparable to chronic hepatitis in man [42]. Rubeanic acid staining revealed copper accumulation in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells / macrophages (Figure 7B). Hepatic copper concentrations were in all cases above 1500 mg/kg dry matter.

RNA isolation and reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

Total cellular RNA was isolated from each frozen Doberman liver tissue in duplicate, using Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Leusden, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA samples were treated with Dnase-I (Qiagen Rnase-free DNase kit). In total 3 μg of RNA was incubated with poly(dT) primers at 42°C for 45 min, in a 60 μl reaction volume, using the Reverse Transcription System from Promega (Promega Benelux, Leiden, The Netherlands).

Q-PCR of oxidative-stress proteins, copper metabolism and other related signaling molecules

Q-PCR was performed on a total of 17 genes involved in oxidative stress and copper metabolism. Real-time PCR was based on the high affinity double-stranded DNA-binding dye SYBR green I (SYBR® green I, BMA, Rockland, ME) and was performed in triplicate in a spectrofluorometric thermal cycler (iCycler®, BioRad, Veenendaal, The Netherlands). For each PCR reaction, 1.67 μl (of the 2× diluted stock) of cDNA was used in a reaction volume of 50 μl containing 1× manufacturer's buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 × SYBR® green I, 200 μM dNTP's, 20 pmol of both primers, 1.25 units of AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk a/d IJssel, the Netherlands), on 96-well iCycler iQ plates (BioRad). Primer pairs, depicted in Table 2, were designed using PrimerSelect software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI). All PCR protocols included a 5-minute polymerase activation step and continued with for 40 cycles (denaturation) at 95°C for 20 sec, annealing for 30 sec, and elongation at 72°C for 30 sec with a final extension for 5 min at 72°C. Annealing temperatures were optimized at various levels ranging from 50°C till 67°C (Table 2). Melt curves (iCycler, BioRad), agarose gel electrophoresis, and standard sequencing procedures were used to examine each sample for purity and specificity (ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyser, Applied Biosystems). Standard curves constructed by plotting the relative starting amount versus threshold cycles were generated using serial 4-fold dilutions of pooled cDNA fractions from both healthy and diseased liver tissues. The amplification efficiency, E (%) = (10(1/-s)-1)·100 (s = slope), of each standard curve was determined and appeared to be > 95 %, and < 105 %, over a wide dynamic range. For each experimental sample the amount of the gene of interest, and of the endogenous references glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) were determined from the appropriate standard curve in autonomous experiments. If relative amounts of GAPDH and HPRT were constant for a sample, data were considered valid and the average amount was included in the study (data not shown). Results were normalized according to the average amount of the endogenous references. The normalized values were divided by the normalized values of the calibrator (healthy group) to generate relative expression levels.

Table 2.

Nucleotide Sequences of Dog-Specific Primers for Quantitative Real-Time PCR

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5'-3') | Tm (°C) | Product size (bp) | Accession number |

| GAPDH | Forward | TGT CCC CAC CCC CAA TGT ATC | 58 | 100 | AB038240 |

| Reversed | CTC CGA TGC CTG CTT CAC TAC CTT | ||||

| HPRT | Forward | AGC TTG CTG GTG AAA AGG AC | 56 | 100 | L77488 / |

| Reversed | TTA TAG TCA AGG GCA TAT CC | L77489 | |||

| SOD1 | Forward | TGG TGG TCC ACG AGA AAC GAG ATG | 64 | 99 | AF346417 |

| Reversed | CAA TGA CAC CAC AAG CCA AAC GAC T | ||||

| CAT | Forward | TGA GCC CAG CCC TGA CAA AAT G | 62 | 119 | AB012918 |

| Reversed | CTC GAG CCC GGA AAG GAC AGT T | ||||

| GSS | Forward | CTG GAG CGG CTG AAG GAC A | 62 | 131 | AY572226 |

| Reversed | AGC TCT GAG ATG CAC TGG ACA | ||||

| GPX1 | Forward | GCA ACC AGT TCG GGC ATC AG | 62 | 123 | AY572225 |

| Reversed | CGT TCA CCT CGC ACT TCT CAA AA | ||||

| CCS | Forward | TGT GGC ATC ATC GCA CGC TCT G | 64 | 96 | AY572228 |

| Reversed | GGG CCG GCC TCG CTC CTC | ||||

| p27KIP | Forward | CGG AGG GAC GCC AAA CAG G | 60 | 90 | AY455798 |

| Reversed | GTC CCG GGT CAA CTC TTC GTG | ||||

| Bcl-2 | Forward | TGG AGA GCG TCA ACC GGG AGA TGT | 61 | 87 | AB116145 |

| Reversed | AGG TGT GCA GAT GCC GGT TCA GGT | ||||

| ATOX1 | Forward | ACG CGG TCA GTC GGG TGC TC | 67 | 137 | AF179715 |

| Reversed | AAC GGC CTT TCC TGT TTT CTC CAG | ||||

| COX17 | Forward | ATC ATT GAG AAA GGA GAG GAG CAC | 60 | 127 | AY603041 |

| Reversed | TTC ATT CTT CAA GGA TTA TTC ATT TAC A | ||||

| ATP7A | Forward | CTA CTG TCT GAT AAA CGG TCC CTA AA | 50 | 99 | AY603040 |

| Reversed | TGT GGT GTC ATC ATC TTC CCT GTA | ||||

| ATP7B | Forward | GGT GGC CAT CGA CGG TGT GC | 56 | 136 | AY603039 |

| Reversed | CGT CTT GCG GTT GTC TCC TGT GAT | ||||

| CP | Forward | AAT TCT CCC TTC TGT TTT TGG TT | 62 | 97 | AY572227 |

| Reversed | TTG TTT ACT TTC TCA GGG TGG TTA | ||||

| MT1A | Forward | AGC TGC TGT GCC TGA TGT G | 64 | 130 | D84397 |

| Reversed | TAT ACA AAC GGG AAT GTA GAA AAC | ||||

| MURR1 | Forward | GAC CAA GCT GCT GTC ATT TCC AA | 58 | 122 | AY047597 |

| Reversed | TTG CCG TCA ACT CTC CAA CTC A | ||||

| XIAP | Forward | ACT ATG TAT CAC TTG AGG CTC TGG TTT C | 54 | 80 | AY603038 |

| Reversed | AGT CTG GCT TGA TTC ATC TTG TGT ATG |

Western blot analysis

Pooled liver tissues (n = 6 dogs) were homogenized in RIPA buffer containing 1 % Igepal, 0.6 mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 17 μg/ml aprotinine and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Sigma chemical Co., Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands). Protein concentrations were obtained using a Lowry-based assay (DC Protein Assay, BioRad). Thirty five μg of protein of the supernatant was denatured in Leammli-buffer supplemented with Dithiothreitol (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 3 min at 95°C and electrophoresed on 10 % Tris-HCl SDS PAGE polyacrylamide gels (BioRad). Proteins were transferred onto Hybond-C Extra Nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences Europe, Roosendaal, The Netherlands) using a Mini Trans-Blot® Cell blot-apparatus (BioRad). The procedure for immunodetection was based on an ECL western blot analysis system, performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Biosciences Europe). The membranes were incubated with 4 % ECL blocking solution and 0.1 % Tween 20 (Boom B.V., Meppel, The Netherlands) in TBS for 1 hour under gentle shaking. The incubation of the primary antibody was performed at room temperature for one hour, with a 1:2000 dilution of mouse anti-horse metallothionein (DakoCytomation B.V., Heverlee, Belgium). After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated chicken anti-mouse (Westburg B.V., Leusden, The Netherlands) at room temperature for one hour. Exposures were made with Kodak BioMax Light-1 films (Sigma chemical Co.).

Total GSH assay

The total amount of GSH was determined by a modified version of a total GSH Determination Colorimetric Microplate Assay according to Allen et al. [45], based on the original Tietze macro assay [46]. Protein samples from Doberman hepatitis (n = 6 dogs) and healthy controls (n = 8 dogs) were isolated as described in Western blot analysis and subsequently pooled. Total protein concentration was measured using a Lowry-based assay (DC Protein Assay, BioRad). In short, 50 μl of the cell-lysate (1 mg/ml) was used in triplicate in a 96-wells plate. The lysates were incubated for 5 minutes with 50 μl of 1.3 mM 5,5'dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB), and 50 μl GSH reductase (1.5 U/ml). To start the reaction 50 μl of NADPH (0.7 mM) was added to the wells. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured at start and after 5 minutes. The rate of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoic acid production (yellow product) was measured in delta absorbance per minute and is directly proportionate with the amount of GSH in the samples. A standard curve was added with known concentrations GSH (0 to 20 μM) in order to determine the GSH concentrations in the samples.

Statistical analysis

A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to confirm normal distribution of every group, and a Levene's test checked the homogeneity of variances across groups. After both verifications, the statistical significance of the difference between the control group and each particular non-healthy group was determined by using the Student's t-Test. The significance level (α) was set at 0.05.

Authors' contributions

BS performed all Q-PCR measurements and wrote the manuscript. PM participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. BA performed the GSH assays and participated with Western blotting. PB performed the Copper measurements on which our groups are based. TI histochemically examined all samples described in this manuscript. GH performed genotyping on Dobermans and provided theoretical background. JR and LP, conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Clare Rusbridge for thoroughly reading this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Bart Spee, Email: B.Spee@vet.uu.nl.

Paul JJ Mandigers, Email: P.j.j.mandigers@planet.nl.

Brigitte Arends, Email: B.Arends@vet.uu.nl.

Peter Bode, Email: P.Bode@iri.tudelft.nl.

Ted SGAM van den Ingh, Email: THI@vet.uu.nl.

Gaby Hoffmann, Email: G.Hoffmann@vet.uu.nl.

Jan Rothuizen, Email: J.Rothuizen@vet.uu.nl.

Louis C Penning, Email: L.C.Penning@vet.uu.nl.

References

- Hamza I, Faisst A, Prohaska J, Chen J, Gruss P, Gitlin JD. The metallochaperone Atox1 plays a critical role in perinatal copper homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6848–6852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111058498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz M. The essential trace elements. Science. 1981;213:1332–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.7022654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra M, Vonk RJ, Kuipers F. How does copper get into bile? New insights into the mechanism(s) of hepatobiliary copper transport. J Hepatol. 1996;24:109–120. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(96)80194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlieb I. Copper and the liver. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:1615–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornburg LP. A perspective on copper and liver disease in the dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000;12:101–110. doi: 10.1177/104063870001200201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood S, Fuentealba IC, Kemp SJ, Trafford J. Copper toxicosis in the Bedlington terrier: a diagnostic dilemma. J Small Anim Pract. 2001;42:181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hultgren BD, Stevens JB, Hardy RM. Inherited, chronic, progressive hepatic degeneration in Bedlington terriers with increased liver copper concentrations: clinical and pathologic observations and comparison with other copper-associated liver diseases. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:365–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CA, Jr, Bowie EJ, McCall JT, Zollman PE. Hemostasis in the copper-laden Bedlington terrier: a possible model of Wilson's disease. Haemostasis. 1980;9:160–166. doi: 10.1159/000214354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twedt DC, Sternlieb I, Gilbertson SR. Clinical, morphologic, and chemical studies on copper toxicosis of Bedlington Terriers. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1979;175:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluis van de BJ, Breen M, Nanji M, Wolferen van M, Jong de P, Binns MM, Pearson PL, Kuipers J, Rothuizen J, Cox DW, Wijmenga C, Oost van BA. Genetic mapping of the copper toxicosis locus in Bedlington terriers to dog chromosome 10, in a region syntenic to human chromosome region 2p13-p16. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:501–507. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluis van de BJ, Rothuizen J, Pearson PL, Oost van BA, Wijmenga C. Identification of a new copper metabolism gene by positional cloning in a purebred dog population. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:165–173. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MA, Schall WD, Jensen RK, Tasker JB. Chronic active hepatitis in 26 Dobermann pinschers. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;187:1343–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingh van den T, Rothuizen J, Cupery R. Chronic active hepatitis with cirrhosis in the Dobermann pinscher. Vet Q. 1988;10:84–89. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1988.9694154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornburg LP. Histomorphological and immunohistochemical studies of chronic active hepatitis in Dobermann Pinschers. Vet Pathol. 1998;35:380–385. doi: 10.1177/030098589803500507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe DS, Twedt DC. Copper-associated hepatopathies in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1995;25:399–417. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(95)50034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandigers PJ, Senders T, Rothuizen J. Morbidity and mortality in a Dutch Dobermann population born between 1993 and 1999. Vet Rec. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mandigers PJ, Ingh van den T, Spee B, Penning LC, Bode P, Rothuizen J. Chronic hepatitis in Doberman pinschers. A review. Vet Q. 2004;26:98–106. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2004.9695173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippard SJ. Free copper ions in the cell? Science. 1999;284:748–749. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomp LW, Lin SJ, Yuan DS, Klausner RD, Culotta VC, Gitlin JD. Identification and functional expression of HAH1, a novel human gene involved in copper homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9221–9226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulpe C, Levinson B, Whitney S, Packman S, Gitschier J. Isolation of a candidate gene for Menkes disease and evidence that it encodes a copper-transporting ATPase. Nat Genet. 1993;3:7–13. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull PC, Thomas GR, Rommens JM, Forbes JR., Cox DW. The Wilson disease gene is a putative copper transporting P-type ATPase similar to the Menkes gene. Nat Genet. 1993;5:327–337. doi: 10.1038/ng1293-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijmenga C, Klomp LW. Molecular regulation of copper excretion in the liver. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:31–9. doi: 10.1079/pns2003316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DW. Genes of the copper pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:828–834. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JS, Gralla EB. Delivering copper inside yeast and human cells. Science. 1997;278:817–818. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris ED. Cellular copper transport and metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:291–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagle MK, Palmiter RD. Coordinate regulation of mouse metallothionein I and II genes by heavy metals and glucocorticoids. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:291–294. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenci P, Zollner G, Trauner M. Hepatic transport systems. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002:105–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.17.s1.15.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetke LM, Chow CK. Copper toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidant nutrients. Toxicology. 2003;189:147–163. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(03)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig S, Wendel A. Glutathione enhancement in various mouse organs and protection by glutathione isopropyl ester against liver injury. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39:1877–1881. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90604-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein E, Ganesh L, Dick RD, Sluis van de B, Wilkinson JC, Klomp LW, Wijmenga C, Brewer GJ, Nabel GJ, Duckett CS. A novel role for XIAP in copper homeostasis through regulation of MURR1. EMBO J. 2004;14:244–254. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandigers PJ, Ingh van den T, Bode P, Rothuizen J. Improvement in liver pathology after 4 months of D-penicillamine in 5 Doberman pinschers with subclinical hepatitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:40–43. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2005)19<40:IILPAM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D, Lichtmannegger J, Heinzman U, Muller-Hocker J, Michaelsen S, Summer KH. Association of copper to metallothionein in hepatic lysosomes of Long-Evans cinnamon (LEC) rats during the development of hepatitis. Eur J Clin Invest. 1998;28:302–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffada AA, Young AP. Coordinated regulation of ceruloplasmin and metallothionein MRNA by interleukin-1 and copper in HepG2 cells. Febs Lett. 1999;457:214–218. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattie MD, Freedman JH. Copper-inducible transcription: regulation by metal- and oxidative stress-responsive pathways. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:293–301. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00293.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcelik D, Ozaras R, Gurel Z, Uzun H, Aydin S. Copper-mediated oxidative stress in rat liver. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2003;96:209–215. doi: 10.1385/BTER:96:1-3:209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoen 't PA, Lans van der CA, Eck van M, Bijsterbosch MK, Berkel van TJ, Twisk J. Aorta of ApoE-deficient mice responds to atherogenic stimuli by a prelesional increase and subsequent decrease in the expression of antioxidant enzymes. Circ Res. 2003;8:262–269. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000082978.92494.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruidenier L, Kuiper I, Duijn van W, Marklund SL, Hogezand van RA, Lamers CB, Verspaget HW. Differential mucosal expression of three superoxide dismutase isoforms in inflammatory bowel disease. J Pathol. 2003;201:7–16. doi: 10.1002/path.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz LO, Kroncke KD, Buchczyk DP, Sies H. Role of copper, zinc, selenium and tellurium in the cellular defense against oxidative and nitrosative stress. J Nutr. 2003;133:1448–1451. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1448S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandigers PJ, Ingh van den T, Bode P, Teske E, Rothuizen J. Association between liver copper concentration and subclinical hepatitis in Doberman pinschers. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:647–650. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2004)18<647:ABLCCA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne CA, Hardy RM, Stevens JB, Perman V. Liver biopsy. Vet Clin North Am. 1974;4:333–350. doi: 10.1016/s0091-0279(74)50034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode P. Automation and Quality Assurance in the Neutron Activation Facilities in Delft. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 2000;245:127–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1006777230207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sterczer A, Gaal T, Perge E, Rothuizen J. Chronic hepatitis in the dog – a review. Vet Q. 2001;23:148–152. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2001.9695104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speeti M, Eriksson J, Saari S, Westermarck E. Lesions of subclinical Dobermann hepatitis. Vet Pathol. 1998;35:361–369. doi: 10.1177/030098589803500505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba I, Haywood S, Trafford DJ. Variations in the intralobular distribution of copper in the livers of copper-loaded rats in relation to the pathogenesis of copper storage diseases. J Comp Pathol. 1989;100:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(89)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S, Shea JM, Felmet T, Gadra J, Dehn PF. A kinetic microassay for glutathione in cells plated on 96-well microtiter plates. Methods Cell Sci. 2000;22:305–312. doi: 10.1023/A:1017585308255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitze F. Enzymatic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total oxidized glutathione: Applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal Biochem. 1969;27:502–522. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]