Abstract

Background—

Farmworkers in the United States, especially migrant workers, face unique barriers to healthcare and have documented disparities in health outcomes. Exposure to pesticides, especially those persistent in the environment, may contribute to these health disparities.

Objective—

Quantify differences in pesticide exposure bioactivity by farmworker category and US citizenship status.

Methods—

We queried the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) from 1999–2014 for pesticide exposure biomarker concentrations among farmworkers and non-farmworkers by citizenship status. We combined this with toxicity assay data from the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Toxicity Forecaster (ToxCast). We estimated adverse biological effects that occur across a range of human population-relevant pesticide doses.

Results—

In total, there were 844 people with any farmwork history and 23,592 non-farmworkers. Of 12 commonly detectable pesticide biomarkers in NHANES, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (OR= 3.76, p= 1.33×10−6) was significantly higher in farmworkers than non-farmworkers. Farmworkers were 1.15 times more likely to have a bioactive pesticide biomarker measurement in comparison to non-farmworkers (adjusted OR=1.15, 95% CI: 0.87, 1.51). Non-U.S. citizens were 1.39 times more likely to have bioactive pesticide biomarker concentrations compared to people with U.S. citizenship (adjusted OR 1.39, 95% CI: 1.17, 1.64). Additionally, non-citizens were significantly more exposed to bioactive levels of -hexachlorocyclohexane (BHC) (OR= 8.10, p= 1.33×10−6), p,p-DDE (OR= 2.60, p= 0.02), and p,p’-DDT (OR= 7.75, p= 0.01).

Significance—

These results highlight pesticide exposure disparities in farmworkers and those without U.S. citizenship. Many of these exposures are occurring at doses which are bioactive in toxicological assays.

Keywords: toxicology, bioactivity, environmental health, human health, pesticides, occupational health, farmworkers

1.1. Introduction

Pesticide exposure has been linked to a myriad of human health outcomes such as obesity, immune alteration, cancer, neurological conditions, type II diabetes mellitus, and death (1–4). More specifically, many pesticides are strong endocrine disruptors because they mimic hormones like estrogens and androgens (4–6). Persistent pesticides last in the environment and human body for years or even decades and can bioaccumulate and bioconcentrate (7). Persistent pesticides include organochlorines like dichlorodiphenyltrichlorethane (DDT), Lindane, Chlordane, Dieldrin, Heptachlor and their metabolites. Non-persistent pesticides include organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids, chlorinated phenols, acyl alanine fungicides and more chemical groups, and were thought to be the less harmful answer to previously used persistent chemicals (e.g. organochlorines) (7). However, non-persistent chemicals still affect human health. While pesticides are associated with endocrine disruption, cancers, and motor neuron disorders, there is still a lack of human health data on the dose-response, toxicological mechanisms, or how population exposure concentrations relate to social determinants of health (8,9).

Social determinants of health like occupation or citizenship can alter both exposure and health outcomes related to chemicals like pesticides (10–12). Healthcare policy and services are limited to non-existent for immigrants and especially migrant workers residing in the United States (US) (13–17). For example, many policies that on the surface appear highly beneficial for the American people like the Affordable Care Act of 2010, actually exclude immigrants completely from accessing care (18). In addition, agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement between the US, Canada, and Mexico limit migrant worker rights (19). Moreover, migrant worker health is often unprotected by the law and workplace discrimination leaves migrant workers very vulnerable (18,20–22). Prior research on migrant workers in the US Midwest found factors like economics, logistics, and health significantly affected the mental health of migrant workers (23). Overall, a gap exists in the quantification of pesticide exposure among farmworkers, and specifically how these exposures may differ by worker category or US citizenship status.

A major challenge in the field of occupational and environmental health is understanding and predicting the health effects of exposure to chemicals like pesticides. There are currently 85,000 chemicals on the global market that Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) has listed in its inventory of substances, and there is little to no experimental toxicology or epidemiology data on many of them (24,25). In 2008, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) collaborated with multiple other federal agencies including the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to create the Toxicology in the 21st Century (Tox21) program (26). The goal of Tox21 is to develop high throughput testing methods to determine the safety of chemicals such as food additives and pesticides. Additionally, Tox21 quantifies the biological mechanisms that chemicals alter to prioritize the chemicals being tested and generate a wealth of data to predict toxicological responses in the human body (24,26). These data are a rich, but untapped, resource to characterize the dose-dependent effects of exposure to pesticides in the context of social determinants of health like occupation and citizenship. This data is then presented in the Toxicity Forecaster (ToxCast).

To address these gaps and understand how pesticide exposure and effects vary by occupation and citizenship, this study’s goal is to determine if people residing in the US are exposed to bioactive concentrations of pesticides. This project has the following aims: 1) quantify and compare pesticide biomarkers among farmworkers and non-farmworkers, 2) quantify and compare pesticide biomarkers between citizen and non-citizen farmworkers, 3) compare exposure concentrations to known bioactive benchmark concentrations in the Tox21 high throughput toxicity data (ToxCast). We hypothesize that the social determinants of health, non-US citizenship and farmworker, will be associated with higher concentrations of pesticides biomarkers. Through this study, a deeper understanding of the variations in pesticide exposure and its association with occupational and citizenship factors can be gained.

1.2. Methods

Our overall study design involves comparing the distributions of chemical biomarker concentrations in The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) with the distributions of doses for those chemicals which exhibit bioactivity in ToxCast. In addition, we quantify which cellular target families are most often affected by these pesticides and look to see how these target families differ by history of farmwork and U.S. citizenship status.

1.2.1. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

NHANES is a cross-sectional study representative of the US population. NHANES is a cross-sectional assessment of the health and nutrition of adults and children residing within the US, with oversampling weights for minoritized populations (27,28). The current iteration of the continuous study began in 1999. Study participants are enrolled on a continuous basis, with data analyzed and deposited in two-year windows. NHANES collects extensive information on the study participants such as self-reported occupation, urinary and serum biomarkers, and self-reported demographics such as age, gender, citizenship, and education.

1.2.2. Study Population

This study included NHANES study participants aged 18 years and older who also had occupation and pesticide exposure data present between 1999 and 2014. This study integrated 28 datasets from NHANES laboratory data to understand pesticide exposure, occupation, and demographics of the study population. From the Industry and Occupation Survey, individuals were coded as “farmworker” or “non-farmworker” using the Current Industry (OCD230=1, OCD231=1), Current Occupation (OCD240=18, OCD241=18), Longest Industry (OCD390=1, OCD391=1), and Longest Occupation (OCD392=18), where all participants who put “Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing” were coded as a farmworker. Starting in the 2015 NHANES cycle, occupation group codes were removed and replaced with work descriptions, breaking down to private industry, different levels of government, self-employed, or working without pay. As we had chosen subjects based on occupation group codes that included the terms agriculture/agricultural or farming for their current or longest job assignment, we decided to focus on 1999–2014 NHANES cycles that identified these groups.

From the demographics data, DMDEDUC2 (older than 18 years of age) and DMDEDUC3 (l8 years of age and younger) were combined to create one education level based on the DMDEDUC2 categories. The US citizenship variable (DMDCITZN) is defined as 1= “Citizen by Birth or naturalization” and 2= “Not a citizen of the US”, and we removed anyone who responded with “Refused”, “Don’t Know”, or skipped the question.

1.2.3. Biomonitoring Samples

NHANES performs chemical biomonitoring in study participants urine and blood (28,29). Participants provided partial urine void in a sterile sampling cup at the mobile examination center. Blood samples are collected by certified laboratory professionals. Urine and blood samples are then analyzed for chemical metabolites using isotope dilution gas chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry (GC/IDHRMS). Pesticide biomarkers measured in blood samples and reported as either 1) fresh weight basis (i.e., pg/g serum) or 2) lipid weight basis (i.e., ng/g lipid). The lipid adjusted values account for blood lipid concentrations and are of particular importance for the accurate quantification of lipophilic pesticides (30). All urinary biomarker measurements were adjusted for urinary creatinine, and all blood pesticide biomarker measurements were blood lipid adjusted.

1.2.4. Toxicity Forecaster Data

The US EPA’s Toxicity Forecaster (ToxCast) is a collection of publicly available high throughput toxicity data intended to make chemical assessment more accessible by allowing researchers to search which chemicals show toxicological effects more easily within human tissue (31). High throughput toxicity screening initiatives have been developed to quantify biological effects of chemicals, including pesticides, in vitro. Dose response curves are created for each chemical and assay, and from these curves the activation concentrations and positive hitcalls (representative of an active assay, bioactive concentration) are defined. ACC (activity concentration at cutoff) is the concentration at which the model reaches the minimum user-defined value for the chemical to be considered active for a given assay (32). The ACC can be used as a proxy of potency to determine the genes, proteins, enzymes, effects on biological pathway and viabilities at which chemicals are active (33,34).

1.2.5. Pesticide Selection Process

The initial pesticides under consideration consisted of all chemicals (except PCBs, dioxins, furans) from NHANES datasets from the following data categories:

“Atrazine and Metabolites”,

“DEET and Metabolites”,

“Dioxins, Furans, & Coplanar PCBs” (dataset includes other organochlorides),

“Environmental Pesticides”,

“Non-persistent Pesticide Metabolites”,

“Pesticides - Carbamates & Organophosphorus Metabolites”,

“Pesticides - Organochlorine Metabolites”, and

“Pyrethroids, Herbicides, & Organophosphorus Metabolites”.

This set of chemicals included 69 different biomarkers present in NHANES.

Detectability percentages of chemicals of interest were calculated by dividing the total number of measurements above LOD (limit of detection) by the total number of the chemical’s measurements in NHANES. To ensure that we included chemicals with values above the limit of detection in most of the study participants, detection frequency percentages of 50% and higher across the population were maintained which resulted in 14 possible chemicals of interest (35). All chemicals in NHANES were present in ToxCast. However, oxychlordane and trans-nonachlor were not maintained in the study because there were no active assays in ToxCast, so these chemicals were removed from consideration, resulting in 12 chemicals for analysis. These chemicals include the following: 2,4-Dichlorophenol (24DCP), 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (24D acid), 2,5-Dichlorophenol (25DCP), 3,5,6-Trichloropyridinol (TCP), 4-Nitrophenol, β-hexachlorocyclohexane (β-HCH), diethyltoluamide acid (DEET acid), Dieldrin, Heptachlor Epoxide, 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA), p,p’-DDE, and p,p’-DDT.

1.2.6. NHANES and ToxCast Data and Variables

All data management and analysis were completed in R version 4.1.3. All code for our work can be found on our GitHub repository (36). Graphics were created using the ggplot2 R package (v3.4.1) (37). All NHANES data was downloaded using the RNHANES package (1.1.0) in R (38). Toxcast data was obtained from the InVitroDB V3.2 database, Level 5, and was downloaded from the EPA’s website (39). Using the corresponding Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Numbers (CASRNs) obtained from PubChem, ACC values from ToxCast were matched to chemical measurements from NHANES survey subjects. The main outcomes of this project include 1) quantifying the distribution of the pesticide concentrations across NHANES and ToxCast, 2) quantifying the demographics of people with and without bioactive measurements, and 3) investigating how bioactivity differs by chemical, farmwork history, and US citizenship status. These outcomes inform the overarching project question of whether people residing in the US are exposed to bioactive levels of pesticides, how these bioactive pesticides affect the body, and whether the rates of exposure to bioactive pesticide concentrations vary based on sociodemographic factors.

Assay data for chemicals of interest from NHANES were extracted from the ToxCast database. We retrieved the hitcall, the activity concentration at cutoff (or ACC), and the intended target family of each ToxCast assay based on the 12 pesticides from NHANES. Using the hitcall variable, we labeled assays as positive (hitcall==1) or negative (hitcall==0) to mean that an assay did or did not show bioactivity by the pesticide. We created a bioactivity ratio per chemical by dividing the number of positive assays by total number of assays.

Any NHANES subject who had at least one chemical measurement equal to or above the minimum ToxCast ACC for that chemical as being “bioactive”. Anyone who did not fit this group was defined as “non-bioactive.” Non-citizen status was determined by the NHANES variable DMDCITZN. We calculated bioactivity by the chemical and marked measurements as bioactive based on their hitcall equaling 1. Education status was constructed NHANES variables DMDEDUC2 and DMDEDUC3 to include four categories: Less than 9th grade, 9–11th grade (Includes 12th grade with no diploma), High school grad/GED or equivalent, and More than high school. Farmworker status was constructed using NHANES industry or occupation group codes for current job (OCD230, OCD231) or longest job (OCD390, OCD391, OCD392) that included the terms agriculture/agricultural or farming.

For lipid adjusted blood measurements, molarity was calculated by multiplying the measurement by serum density of 1.024 g/mL and dividing by molecular weight (40). Urinary measurements were calculated by diving the measurement by molecular weight. All measurements of molarity have units of μmol/L.

1.2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data from the 1999–2002, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2011–2012 and 2013–2014 data collection cycles were appended, and the sampling weights modified as directed in NHANES documentation. Statistical analysis was done with the R survey package (v4.1–1) to handle complex survey designs present in NHANES. The function survey::svydesign was used to handle sampling weights, with primary sampling units nested within each stratum. Removal of observations with missing data was done for all analyses using the subset function within survey::svydesign.

Differences in demographic factors by group or citizenship were tested using a Pearson’s chi-square test, using a Rao and Scott Adjustment where necessary for categorical variables. Low response was defined as 8 or less respondents within one stratum. For continuous variables, a Wilcoxon Rank test was used to test group means, with a Kruskall-Wallis Correction. All demographic significance testing was completed using the NHANES Full Sample 2 and 4 Year MEC Exam Weights. A new weight variable titled “MEC16YR” was created using the weighted MEC 2- and 4-year measurements to represent the weights used from 1999–2002 and each year after, respectively.

Both unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression was conducted on individual chemicals in relation to farmworker and non-citizen status using the survey::svyglm function using a quasi-binomial model with a logit link. The outcome variable for chemicals was constructed as an indicator variable, with a 1 indicating the measurement was considered chemically bioactive. Adjusted logistic regression included variables for age at screening, race-ethnicity, BMI, education, and survey year for all chemicals, and the additional inclusion of creatine molarity for urinary measurements (Supplementary Tables 2–3). Adjusted linear regression models were also constructed, using chemical molarity instead of a bioactive indicator variable (Supplementary Table 4). P-values for all tested chemicals were FDR (false discovery rate) adjusted and ROC AUCs (area under the curve) to determine the discrimination performance measurement for classification (Supplementary Tables 2–3) were calculated using the WeightedROC R package (v2020.1.31) (41). Estimated probabilities of bioactivity were calculated from the adjusted logistic regression models, stratified by farmworker and citizen status to further explore these subgroups (Supplementary Figures 1–7).

Non-parametric Wilcoxon Mann Whitney U tests were conducted to test differences in individual chemical concentrations in relation to farmworker or non-citizen status using the survey::svyranktest function (Supplementary Table 5). The outcome variable for chemicals was calculated as the log molarity for blood measurements and the log of the ratio of the chemical molarity to creatine molarity for urinary measurements. P-values for all tested chemicals were FDR adjusted and AUCs for model performance measurement were calculated using the U statistic (42).

1.3. Results

We first assessed demographic features of the study participants based on whether the participant had a history of farmwork or not (Tables 1 and 2). In total, there were 844 people who reported any farmwork history, and 23,592 who were categorized as non-farmworkers (Table 1, Supplementary Figure 8). The farmworker group was mostly men (554, 65.6%), Non-Hispanic White (414, 49.1%), U.S. Citizens (627, 74.3%) and 19.2% reported high school graduate or a GED (162). The non-farmworker group had similar mean BMI and age. The non-farmworker group is predominantly women (12,034, 51.0%), Non-Hispanic White (10,871, 53.8%), had U.S. Citizenship (20,596, 87.3%), and 28.8% reported high school graduate or a GED (6,798).

Table 1.

Stratified demographics of NHANES participants, by farmwork category.

| Non-farmworker | Farmworker | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=23,592) | (N=844) | |||||||

| Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | |||||

| Variable | Mean | Std Dev | Mean, Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean, Std Dev | p-value | |

| Body Mass Index | 28.61 | 6.73 | 28.46, 6.62 | 28.53 | 5.87 | 28.64, 6.26 | 0.2864 | |

| Age in Years | 47.03 | 18.95 | 45.67, 17.13 | 52.61 | 19.74 | 49.19, 18.06 | 0.0001755 | |

| N | % | % | N | % | % | |||

| Survey Year | 1999–2000 | 1,423 | 7.4 | 6.2 | 78 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 7.30E-08 |

| 2001–2002 | 1,583 | 8.3 | 6.7 | 109 | 12.9 | 11.8 | ||

| 2003–2004 | 3,075 | 16.0 | 13.4 | 178 | 21.1 | 26.5 | ||

| 2005–2006 | 249 | 1.3 | 14.5 | 78 | 9.2 | 7.4 | ||

| 2007–2008 | 3,641 | 19.0 | 14.7 | 88 | 10.4 | 7.8 | ||

| 2009–2010 | 3,781 | 19.7 | 14.5 | 148 | 17.5 | 15.8 | ||

| 2011–2012 | 3,239 | 16.9 | 14.5 | 89 | 10.5 | 13.3 | ||

| 2013–2014 | 3,601 | 18.8 | 15.5 | 76 | 9.0 | 8.4 | ||

| Gender | Men | 11,558 | 49.0 | 48.5 | 554 | 65.6 | 61.9 | 5.24E-06 |

| Women | 12,034 | 51.0 | 51.5 | 290 | 34.4 | 38.1 | ||

| Racial Ethnicity | Mexican American | 3,927 | 19.4 | 7.4 | 277 | 32.8 | 16.6 | < 2.2E-16 |

| Other Hispanic | 1,754 | 8.7 | 4.9 | 26 | 3.1 | 2.3 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 10,871 | 53.8 | 69.6 | 414 | 49.1 | 70.6 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1,835 | 9.1 | 11.5 | 87 | 10.3 | 6.1 | ||

| Other Race | 1,835 | 9.1 | 6.6 | 40 | 4.7 | 4.3 | ||

| U.S. Citizenship | Non-Citizen | 2,996 | 12.7 | 8.2 | 217 | 25.7 | 15.7 | 1.12E-09 |

| Citizen | 20,596 | 87.3 | 91.8 | 627 | 74.3 | 84.3 | ||

| Education Level | Less than 9th grade | 2,282 | 9.7 | 5.1 | 266 | 31.5 | 17.4 | < 2.2E-16 |

| 9–11th grade | 3,903 | 16.5 | 12.3 | 126 | 14.9 | 12.7 | ||

| Highschool | 5,715 | 24.2 | 23.9 | 167 | 19.8 | 22.5 | ||

| Graduate/GED | 6,798 | 28.8 | 31.3 | 162 | 19.2 | 26.4 | ||

| Some College or AA | 4,894 | 20.7 | 27.4 | 123 | 14.6 | 20.9 | ||

P-values are derived from a chi-square test, using a Yate’s Correction where necessary, and for continuous variables, a Wilcoxon Rank Test was used with a Kruskall-Wallis Correction (as needed). Percentages are out of the total number of respondents for that specific question. In this table, other race includes multi-racial. In this study, 9–11 grad includes 12th grade completion without a high school diploma.

Table 2.

Stratified demographics of NHANES participants with a history of farmwork, by citizenship.

| Citizen | Non-citizen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=627) | (N=217) | |||||||

| Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | |||||

| Variable | Mean | Std Dev | Mean, Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean, Std Dev | p-value | |

| Body Mass Index | 28.76 | 6.22 | 28.76, 6.52 | 27.89 | 4.7 | 27.98, 4.58 | 0.4221 | |

| Age in years | 55.45 | 19.75 | 50.59, 18.23 | 44.41 | 17.34 | 41.67, 15.06 | 8.89E-08 | |

| N | % | % | N | % | % | |||

| Survey Year | 1999–2000 | 62 | 9.9 | 9.4 | 16 | 7.4 | 7.0 | 0.04774 |

| 2001–2002 | 83 | 13.2 | 12.3 | 26 | 12.0 | 8.9 | ||

| 2003–2004 | 156 | 24.9 | 29.1 | 22 | 10.1 | 12.3 | ||

| 2005–2006 | 41 | 6.5 | 6.2 | 37 | 17.1 | 14.1 | ||

| 2007–2008 | 68 | 10.8 | 7.7 | 20 | 9.2 | 8.3 | ||

| 2009–2010 | 101 | 16.1 | 14.8 | 47 | 21.7 | 21.3 | ||

| 2011–2012 | 64 | 10.2 | 13.0 | 25 | 11.5 | 14.7 | ||

| 2013–2014 | 52 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 24 | 11.1 | 13.5 | ||

| Gender | Men | 397 | 63.3 | 59.8 | 157 | 72.4 | 73.1 | 0.01068 |

| Women | 230 | 36.7 | 40.2 | 60 | 27.6 | 26.9 | ||

| Racial Ethnicity | Mexican American | 98 | 15.6 | 5.9 | 179 | 82.5 | 74.1 | < 2.2E-16 |

| Other Hispanic | 18 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 8 | 3.7 | 4.8 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 406 | 64.8 | 81.9 | 8 | 3.7 | 9.8 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 81 | 12.9 | 6.8 | 6 | 2.8 | 2.7 | ||

| Other Race | 24 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 16 | 7.4 | 8.6 | ||

| Education Level | Less than 9th grade | 122 | 19.5 | 9.9 | 144 | 66.4 | 57.9 | < 2.2E-16 |

| 9–11th grade | 92 | 14.7 | 12.4 | 34 | 15.7 | 14.8 | ||

| Highschool | 142 | 22.6 | 23.3 | 25 | 11.5 | 18.3 | ||

| Graduate/GED | 155 | 24.7 | 30.8 | 7 | 3.2 | 2.9 | ||

| Some College or AA | 116 | 18.5 | 23.6 | 7 | 3.2 | 6.2 | ||

P-values are derived from a chi-square test, using a Yate’s Correction where necessary, and a Wilcoxon Rank Test was completed with a Kruskall-Wallis Correction. Percentages are out of the total number of respondents for that specific question. In this table, other race includes multi-racial. In this study, 9–11 grad includes 12th grade completion without a high school diploma.

To better understand how each of the chemicals relate to each other, Table 3 outlines the pesticides by persistence and frequencies of activity of ToxCast assays. In total, there are 12 pesticides that are detectable in NHANES study participants and also assayed in ToxCast. Overall, there were 5 persistent organic pesticides and 7 non-persistent pesticides included in this study. The top three most bioactive pesticides in ToxCast were p,p’-DDT had the highest percentage of assays which were “active” (36.18%), followed by heptachlor epoxide (35.47%) and p,p’- DDE (32.72%). The bioactivity threshold is the lowest ACC of the active assays for a given chemical. These values ranged from 6.5nM (2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) to 1.35μM (3,5,6-Trichloropyridinol).

Table 3.

Bioactivity of pesticides cross-listed between NHANES and ToxCast, by pesticide and persistence.

| Common Name | CAS-RN | Total Assays | Positive Assays | Bio-active Assay Percentage | Bioactivity Threshold (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-Dichlorophenol | 120-83-2 | 701 | 28 | 3.99 | 0.34 |

| 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid | 94-75-7 | 836 | 23 | 2.75 | 0.0065 |

| 2,5-Dichlorophenol | 583-78-8 | 626 | 13 | 2.08 | 0.33 |

| 3,5,6-Trichloropyridinol | 6515-38-4 | 573 | 30 | 5.24 | 1.35 |

| 3-Phenoxybenzoic acid | 3739-38-6 | 762 | 13 | 1.71 | 0.399 |

| 4-Nitrophenol | 100-02-7 | 705 | 48 | 6.81 | 0.0086 |

| DEET acid | 134-62-3 | 797 | 17 | 2.13 | 1.05 |

| p,p’-DDTa | 50-29-3 | 691 | 250 | 36.18 | 0.43 |

| Dieldrina | 60-57-1 | 700 | 150 | 21.43 | 0.32 |

| Heptachlor epoxidea | 76-44-8 | 671 | 238 | 35.47 | 1.31 |

| ß-hexachlorocyclohexanea | 319-85-7 | 675 | 28 | 4.15 | 0.15 |

| p,p’-DDEa | 72-55-9 | 703 | 230 | 32.72 | 0.31 |

A positive assay is defined as hitcall==1. The bioactivity assay percentage is created by dividing the total number of positive assays by the total number of assays and multiplying by 100%. Bioactivity ratio per chemical was calculated by dividing the count of positive assays by the total number of assays within the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxicity Forecaster database.

Persistent Organic Pollutant.

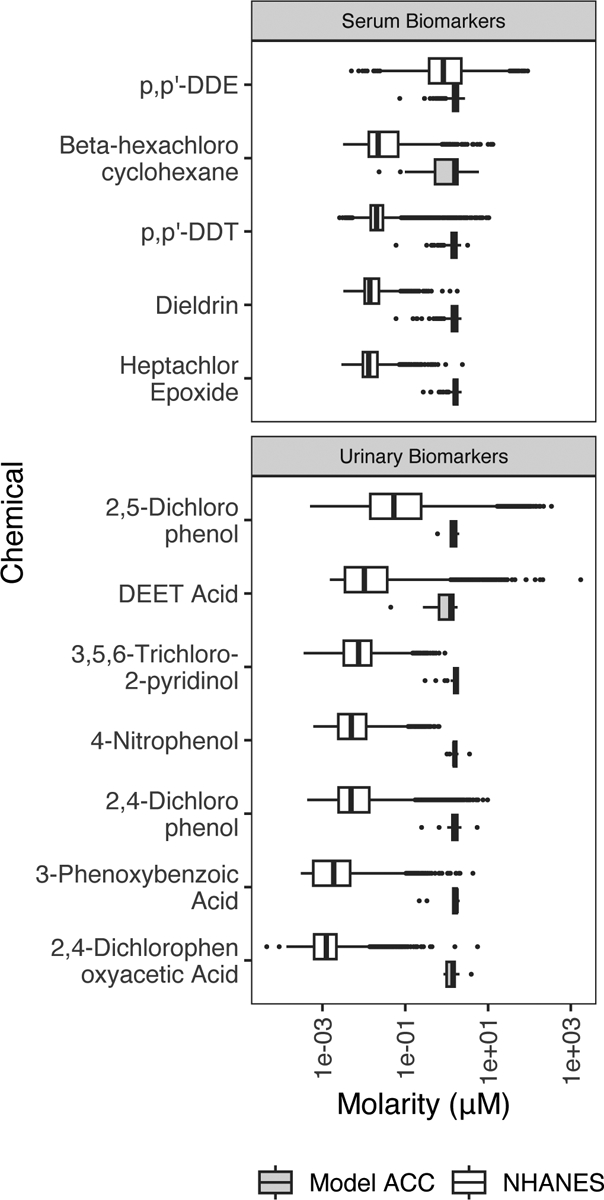

Next, we wanted to compare the concentrations of chemicals required to activate the ToxCast assays to the biomarker concentrations measured in people in NHANES. Figure 1 presents the distribution of pesticide concentrations among people residing in the United States in white (retrieved from NHANES), and in gray, the ACCs of active assays retrieved from ToxCast. In this figure, where the pesticide distributions of exposure and bioactivity overlap represents pesticide exposures among the US population that are “bioactive”. Additionally, 4-nitrophenol is the only pesticide biomarker in NHANES that does not have human measurements that overlap with the bioactive distribution in NHANES.

Figure 1.

Comparison of chemical biomarker concentrations, converted to molarity units, in NHANES participants and concentrations for bioactivity in vitro from ToxCast. There are a portion of NHANES subjects who have serum and/or urinary chemical measurements that meet or exceed bioactivity thresholds. Chemical molarity measurements taken from NHANES subjects are shown as the top boxplot for each chemical, shaded in white. Model ACCs (activity concentration at cutoff) from ToxCast are the minimum concentration for a specific assay where a chemical is considered active (bottom boxplot for each chemical, shown in gray).

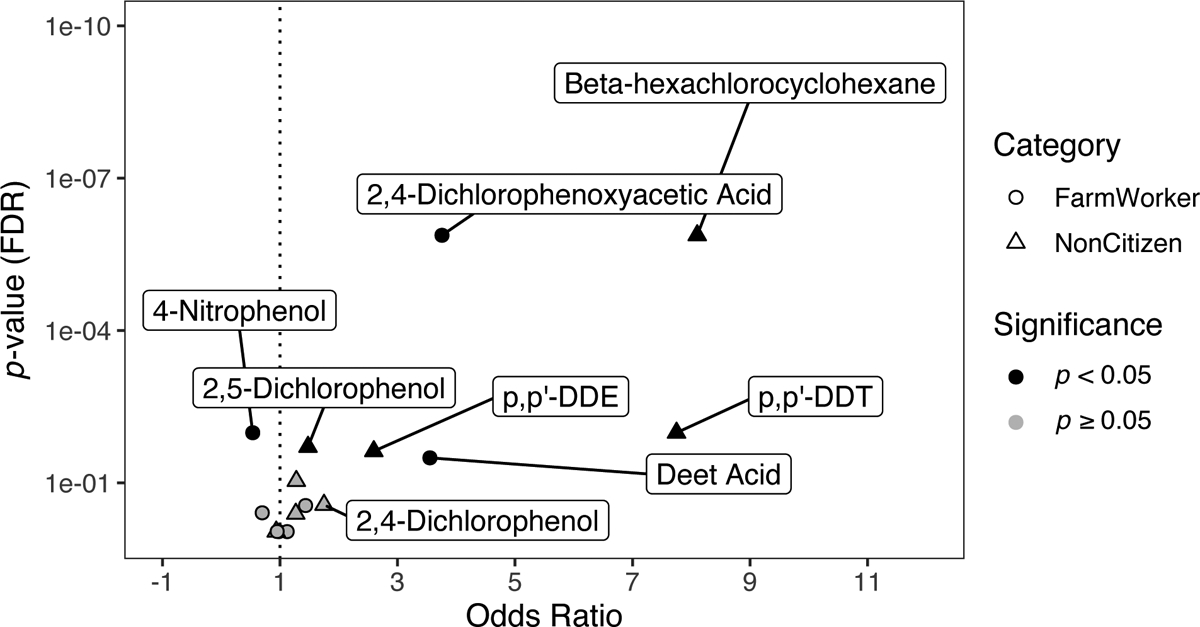

We present the Mann-Whitney-U Rank Test outcomes by chemical in Supplementary Table 5 to test for differences in biomarker concentration by farmworker status or US citizenship. When quantifying the odds of having a bioactive measurement (unadjusted outcomes in Supplemental Table 2, fully adjusted outcomes presented in Figure 2 and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4), we found farmworkers were 3.8 times more likely to have a bioactive measurement in comparison to non-farmworkers for 2,4-D (p=1.3×10−6) and 3.55 times more for DEET acid (p=0.02), while farmworkers were significantly less likely to have a bioactive measurement of 4-Nitrophenol (p= 0.01). Next, we found subjects living without U.S. citizenships were significantly more likely to be exposed to a bioactive measurement of BHC (OR=8.1, p-value=1.3×10−6, U=11.94), p,p’-DDE (OR=2.6, p-value=0.02, U=8.72), p,p-DDT (OR=7.8, p-value. =0.01, U=6.29).

Figure 2.

Volcano plot depicting the outcomes of the regression model of odds of having a measurement of a chemical at a bioactive concentration by history of farmwork or US citizenship. Farmworkers and/or non-US citizens generally have greater odds of having bioactive concentrations of some pesticides. Bioactive was defined as having at least one pesticide biomarker concentration that was the same or higher concentration than the minimal concentration needed to see an effect. The data for this table was retrieved from the U.S. EPA’s ToxCast and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

When trying to understand what intended target families are most affected by these chemicals, Supplementary Table 6 provides the frequency of intended target families by the pesticide. Based on individual intended assay target count, cell cycle (N=487), nuclear receptor (N=318), cytokine (N=143), DNA binding (N=172), and cell adhesion molecules (N=65) were the most frequent targets of the pesticides. Overall, p,p’-DDE (N=305) had the most intended target family counts based on positive assays, followed by p,p’-DDT (N=278), and heptachlor epoxide (N=259). Heptachlor epoxide had the highest number of positive assays targeting the cell cycle (N=123) and p,p’-DDT had the second most (N=120). Additionally, for p,p’-DDE had mostly nuclear receptor targeting positive assays (N=102), followed by the cell cycle (N=74) and DNA binding (N=64).

Despite the limitation of a small sample size of data, which restricts the power to examine non/US-citizen subgroups within farmers, efforts were made to gather valuable insights for future studies. An exploratory analysis was conducted, whereby estimated probabilities of bioactive chemical concentrations were calculated using significant adjusted logistic regression models (Supplemental Figures 1–7). Results were stratified based on the significant adjustment factors of race/ethnicity and education. In general, non-citizens (farmworker and/or non-farmworker) had the highest probability of testing for a bioactive concentration for the chemicals of interest, except for DEET acid, which tested highest in US-citizen farmworkers (Supplemental Figure 5).

1.3.1. Discussion

When looking at individuals who have pesticide biomarker concentrations at these bioactive levels, demographics statistically differed based on bioactivity, farmwork history, and citizenship status. We found NHANES participants are broadly exposed to bioactive concentrations of pesticides. Heptachlor epoxide, p,p’-DDT, and p,p’-DDE were the most bioactive pesticides in ToxCast based on overall percent of positive assays. Disproportionate exposures to bioactive concentrations of pesticides were particularly evident in farmworkers without U.S. citizenship, particularly for persistent pesticides.

The exploratory analysis of farmers’ subgroup revealed intriguing findings that warrant further investigation. Supplemental Figure 2 indicates an increase in p,p’-DDE levels with age and an increase among non-citizens, with no significant influence from farmworker status or other variables. The elevated probability of having a bioactive concentration of p,p’-DDE in Mexican Americans implies that both US and non-US citizens of Mexican heritage may have encountered DDT exposure in Central America at a later stage compared to their US-born counterparts. Supporting these findings, Supplemental Figure 3 demonstrated higher exposure levels to DDT among non-citizens of Mexican and Non-Hispanic Black origin compared to non-Hispanic White individuals. This aligns with expectations, considering the delayed discontinuation of DDT use in Central America and certain regions of the African diaspora, particularly in areas with a high malaria risk (43,44). These disparities emphasize the potential influence of geographic and cultural factors on DDT exposure within the farming community.

Farmworker status was also found to be associated with an increase in DEET acid, a metabolite of DEET, with this relationship being even less dependent on non-citizenship status (Supplementary Figure 5). DEET remains a commonly used insect repellent, both for recreational and commercial purposes (45).

Pesticide exposures have been associated with increased mortality due to cancer, diabetes mellitus, poisonings, and tuberculosis and other lung infection (46,47). Pesticide exposure throughout the life course has been associated with breast cancer and dysregulated mammary gland development. For example, mothers with the highest p,p-DDT concentrations were 3.7 times more likely to have daughters who developed cancer by the age of 52 in comparison to mothers with the lowest p,p-DDT blood concentrations (48). Women who are farmworkers and not US citizens could be at increased risk of exposure-associated diseases like breast cancer – these findings warrant further investigation in this area.

Citizenship status is also a known barrier to health insurance and treatment (49,50), potentially compounding adverse effects of exposure to toxic chemicals like pesticides. In a study of 2,702 participants living with diabetes, non-citizens had a greater risk for poor glycemic management (OR=5.16, 95% CI: 3.73, 6.04) in comparison to citizens by birth (50). Citizens by naturalization were also at an increased risk of poor glycemic management (OR=1.95, 95% CI: 1.49,2.55) (50). Additionally, this study found that individuals with diabetes and without health insurance were almost twice as likely to have poor glycemic management compared to insured people (OR=1.99, 95% CI: 1.53–2.59). Similar outcomes have also been noted in cardiovascular disease. Using NHANES, researchers retrieved data from 2011 to 2016 to investigate prevalence, treatment, and control of hypercholesterolemia, included 11,680 US-born citizens, 2,752 foreign born citizens, and 2,554 non-citizens (49). In that study, over half of non-citizens did not have health insurance (52.2); which was significantly more than US-born citizens (13.6%, p<0.001) (49).

Non-citizens also had significantly higher prevalence of diabetes (15.7% vs. 12.8%, p<0.001) (49). Treatment percentages were also significantly lower among non-citizens than US-born citizens with hypercholesteremia (16.4% vs 45.5%), hypertension (60.3% vs. 81.1%), and diabetes (51.2% vs. 69.5%) (p<0.001) (49). Among noncitizens, those without a usual source of health care or health insurance had lower treatment percentages for hypercholesteremia (2.7% and 8.1%), hypertension (22.2% and 39.1%), and diabetes (15.5% and 28.6%) (49). It is very important to understand that overall, environmental risk factors of the many pesticides on the global market are still poorly characterized across the literature.

1.3.2. Limitations and Strengths

Our research shows that NHANES respondents are exposed to multiple pesticides and pesticide types. Quantifying chemical mixtures across a population is complex and methodology for understanding these mixtures is still an emerging area of research. However, there is still plenty of research to be done in understanding chemical mixtures. Much of the research on chemical health outcomes focuses on one chemical at a time, including our study, but people are often exposed to more than one chemical, chemicals can interact with each other to create new chemicals and once chemicals are in the environment, they can also react with the ambient air or be degraded by the sun’s rays. All these changes to chemicals in relation to mixtures and being in the environment create nuanced exposures and further research is needed to understand how these mixtures may uniquely affect the human body.

Some pesticides which did not meet our inclusion criteria could have different exposure based on farmwork occupational status. Desethyl hydroxy DEET (17.37% vs. 11.30%, p =0.015) and DEET (9.17% vs 6.25%, p = 0.036) were significantly different between farmworkers and non-farmworkers, respectively. However, all of these chemicals had detectability percentages below the cutoff for inclusion in our study. It is possible that by restricting the chemicals included we are missing some important differences in pesticide exposure between farmworkers and non-farmworkers. Studying exposures and effects of these less commonly detected pesticides could be an important area of investigation.

One of the major limitations of this project is that while NHANES is thorough, reliable, and valid study, it is still cross-sectional. This means the measurements within it are a single measurement in time and cannot be fully representative of chronic exposures or chronic symptomology due to exposures. Another limitation includes most farmworkers being recruited between 1999 and 2004 (N= 1,775, 69.6%), which is of importance since the recruitment and laboratory methods have been updated since 2003. Newer methods for quantifying chemicals from blood and urine samples are more sensitive and can detect lower quantities of chemicals. Additionally, farmworkers living without citizenship had significantly lower BMI as well, which may impact metabolism and accumulation of chemicals in the body.

An additional limitation of this study is that not every chemical is measured in every participant, and that not every assay is completed in each chemical. This limitation makes direct comparisons impossible and therefore our results are somewhat limited to group means. There are some known limitations to the ToxCast dataset such as interference of cytotoxicity. Non-specific cell stress can interfere with the frequency reading since the cell is overworking to re-gain homeostasis after chemical exposure. ToxCast assays are often assessing effects in a single tissue cell type, which may not accurately reflect chemical sensitivity across organ systems or within particularly susceptible individuals. Moreover, while ToxCast maintains a robust suite of assays measuring effects across a broad spectrum of potential toxic outcomes, not every chemical is tested for every assay and not all potential biological outcomes following chemical exposure are captured.

Other limitations inherent to interpreting bioactivity also exist. For starters, urine and serum concentrations reflect excreted or circulating concentrations, respectively, but may not be representative of concentrations in target organs like fat, liver, kidneys, or brain. This is important because many chemicals target specific organs (e.g., organochlorines targeting the central nervous system) or bioaccumulate in specific tissue types like lipids. There are also challenges to being able to relate metabolites to their parent compounds since some chemicals can have more than one parent compound (e.g. the pyrethroid metabolite 3-PBA). This can make ascertaining what active ingredient is bioactive in the human body difficult, and even if considering a limited number of chemicals, there is no way to calculate a direct contribution of each parent compound to a non-specific metabolite.

A strength of our study is that it is the first to provide a comprehensive quantification of all the pesticide exposure concentrations within the US population using NHANES from 1999 to 2014 and to then stratify these concentrations by social determinants of health with a focus on farmwork, fishing, and forestry work history and U.S. citizenship. By considering all the pesticides within NHANES and narrowing down to those with at least 50% detectability, we find that even within NHANES a small portion (15%) of these chemicals are detected in a majority of NHANES participants. ToxCast & NHANES are both validated, reliable study datasets created by the US government to assess chemical bioactivity and examine the health of people residing in the US. By integrating these two datasets, the results are more generalizable to the U.S. population. Additionally, this study is one of few to consider health disparities associated with occupation or citizenship and how they may affect pesticide exposure and potential resultant health effects. This project can inform evidence-based guidelines and policies that are focused on reducing pesticide exposure concentrations among people residing within the United States.

1.3.3. Future Directions

While NHANES quantifies many chemical biomarker concentrations for each study participant, these measures do not fully capture how many chemicals each person may be exposed to since every chemical is not tested for in every person. Moreover, toxicological research should continue to focus on novel methods for assessing toxicity of chemical mixtures and interactions to better understand population pesticide exposure and bioactivity of combined pesticide exposures in at-risk individuals. Currently, research looks at predominantly the active ingredients of pesticides, but inactive ingredients used to create pesticides may also influence human health, this is currently being missed in many toxicological studies. Future research can also include temporal data on pesticide exposure. Both NHANES and ToxCast include singular exposure time points in humans and in vitro, respectively. However, for many farmworkers, pesticide exposure is chronic and happens over multiple exposure incidents.

Expanding this research to disease biomarkers, symptoms, and diagnoses will also be an important future direction. This way we can better connect target families of ToxCast assays to health outcomes and then stratify findings by occupation and social determinants of health like income, gender, citizenship, and country of birth. In this same vein of understanding social determinant effects on health, more research on how these biomarker concentration distributions differ based on residing or working in a low versus high income country will be important because laws within a nation can alter the health and exposure for many.

Supplementary Material

Impact Statement.

Farmworkers are a vulnerable population due to social determinants of health and occupational exposures. Here, we integrate US population chemical biomonitoring data and toxicity outcome data to assess pesticide exposure by farmwork history and citizenship. We find that farmworkers and those without US citizenship are significantly more likely to be exposed to concentrations of pesticides which are bioactive in toxicological assays. Thus, farmworkers employed in the US but who are not citizens could be at increased risk of harm to their health due to pesticides. These findings are important to shape evidence-based policies in regulatory science to promote worker safety.

Acknowledgements:

Authors have no acknowledgements to address in this section.

Funding:

The researchers included on this study were supported by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health Education Research Center (Grant# T42 OH 008455), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Environmental Toxicology and Epidemiology Program (Grant# T32 ES007062), the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Program (Grant # DGE-1256260), and the National Institutes of Health (R01 ES028802, P30 ES017885, R01AG072396).

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: Analysis was conducted on publicly available datasets and so ethical approval was not required.

Competing Interests: The authors do not declare any financial conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The NHANES and ToxCast datasets analysed during the current study are available from the CDC, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/, and the EPA, https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/exploring-toxcast-data.

References

- 1.Wei Y, Zhu J, Nguyen A. Urinary concentrations of dichlorophenol pesticides and obesity among adult participants in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2008. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014. Mar;217(2–3):294–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zong G, Valvi D, Coull B, Göen T, Hu FB, Nielsen F, et al. Persistent organic pollutants and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective investigation among middle-aged women in Nurses’ Health Study II. Environ Int. 2018. May;114:334–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medehouenou TCM, Ayotte P, Carmichael PH, Kröger E, Verreault R, Lindsay J, et al. Exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides and risk of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in an older population: a prospective analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Environ Health. 2019. Dec;18(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martyniuk CJ, Mehinto AC, Denslow ND. Organochlorine pesticides: Agrochemicals with potent endocrine-disrupting properties in fish. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2020. May;507:110764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briz V, Molina-Molina JM, Sánchez-Redondo S, Fernández MF, Grimalt JO, Olea N, et al. Differential Estrogenic Effects of the Persistent Organochlorine Pesticides Dieldrin, Endosulfan, and Lindane in Primary Neuronal Cultures. Toxicol Sci. 2011. Apr;120(2):413–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong HL, Garthwaite DG, Ramwell CT, Brown CD. Assessment of occupational exposure to pesticide mixtures with endocrine-disrupting activity. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019. Jan;26(2):1642–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abubakar Y, Tijjani H, Egbuna C, Adetunji CO, Kala S, Kryeziu TL, et al. Chapter 3 - Pesticides, History, and Classification. In: Egbuna C, Sawicka B, editors. Natural Remedies for Pest, Disease and Weed Control. Academic Press; 2020. p. 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mostafalou S, Abdollahi M. Pesticides and human chronic diseases: Evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013. Apr;268(2):157–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhananjayan V, Ravichandran B. Occupational health risk of farmers exposed to pesticides in agricultural activities. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health. 2018. Aug;4:31–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaga K, Dharmani C. Sources of exposure to and public health implications of organophosphate pesticides. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2003. Sep;14(3):171–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das R, Steege A, Baron S, Beckman J, Harrison R. Pesticide-related Illness among Migrant Farm Workers in the United States. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2001. Oct;7(4):303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García-García CR, Parrón T, Requena M, Alarcón R, Tsatsakis AM, Hernández AF. Occupational pesticide exposure and adverse health effects at the clinical, hematological and biochemical level. Life Sci. 2016. Jan;145:274–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes SM. An Ethnographic Study of the Social Context of Migrant Health in the United States. Gill P, editor. PLoS Med. 2006. Oct 24;3(10):e448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace SP, Rodriguez M, Padilla-Frausto I, Arredondo A, Orozco E. Improving access to health care for undocumented immigrants in the United States. Salud Pública México. 2013. Aug 6;55(Suppl 4):508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall E, Cuellar NG. Immigrant Health in the United States: A Trajectory Toward Change. J Transcult Nurs. 2016. Nov;27(6):611–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bustamante AV, Chen J, Félix Beltrán L, Ortega AN. Health Policy Challenges Posed By Shifting Demographics And Health Trends Among Immigrants To The United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021. Jul 1;40(7):1028–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Delivery of Health Services to Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007. Apr 1;28(1):345–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quesada J, Hart LK, Bourgois P. Structural Vulnerability and Health: Latino Migrant Laborers in the United States. Med Anthropol. 2011. Jul;30(4):339–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes N Is health a labour, citizenship or human right? Mexican seasonal agricultural workers in Leamington, Canada. Glob Public Health. 2013. Jul 10;8(6):654–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos A, Carlo G, Grant K, Trinidad N, Correa A. Stress, Depression, and Occupational Injury among Migrant Farmworkers in Nebraska. Safety. 2016. Oct 22;2(4):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramos AK. A Human Rights-Based Approach to Farmworker Health: An Overarching Framework to Address the Social Determinants of Health. J Agromedicine. 2018. Jan 2;23(1):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saxton DI, Stuesse A. Workers’ Decompensation: Engaged Research with Injured Im/migrant Workers: Anthropology of Work Review. Anthropol Work Rev. 2018. Dec;39(2):65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos AK, Su D, Lander L, Rivera R. Stress Factors Contributing to Depression Among Latino Migrant Farmworkers in Nebraska. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015. Dec;17(6):1627–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Attene-Ramos MS, Miller N, Huang R, Michael S, Itkin M, Kavlock RJ, et al. The Tox21 robotic platform for the assessment of environmental chemicals – from vision to reality. Drug Discov Today. 2013. Aug;18(15–16):716–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adeola FO. Global impact of chemicals and toxic substances on human health and the environment. In: Kickbusch I, Ganten D, Moeti M, editors. Handbook of Global Health [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. [cited 2023 Jan 9]. p. 2227–56. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-45009-0 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas R, Paules RS, Simeonov A, Fitzpatrick SC, Crofton KM, Casey WM, et al. The US Federal Tox21 Program: A strategic and operational plan for continued leadership. ALTEX. 2018;35(2):163–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data [Internet]. National Center for Health Statistics. 2023. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curtin LR, Mohadjer LK, Dohrmann SM, Montaquila JM, Kruszan-Moran D, Mirel LB, et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design,1999–2006. Vital Health Stat 2. 2012;155:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calafat AM. The U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and human exposure to environmental chemicals. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2012. Feb;215(2):99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barr DB, Wilder LC, Caudill SP, Gonzalez AJ, Needham LL, Pirkle JL. Urinary Creatinine Concentrations in the U.S. Population: Implications for Urinary Biologic Monitoring Measurements. Environ Health Perspect. 2005. Feb;113(2):192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Toxicity Forecasting [Internet]. Safer Chemicals Research | US EPA. 2023. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/toxicity-forecasting

- 32.Filer DL, Kothiya P, Setzer RW, Judson RS, Martin MT. tcpl: the ToxCast pipeline for high-throughput screening data. Wren J, editor. Bioinformatics. 2017. Feb 15;33(4):618–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blackwell BR, Ankley GT, Corsi SR, DeCicco LA, Houck KA, Judson RS, et al. An “EAR” on Environmental Surveillance and Monitoring: A Case Study on the Use of Exposure–Activity Ratios (EARs) to Prioritize Sites, Chemicals, and Bioactivities of Concern in Great Lakes Waters. Environ Sci Technol. 2017. Aug 1;51(15):8713–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Putzrath RM. Estimating Relative Potency for Receptor-Mediated Toxicity: Reevaluating the Toxicity Equivalence Factor (TEF) Model. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1997;25(1):68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silver MK, Arain AL, Shao J, Chen M, Xia Y, Lozoff B, et al. Distribution and predictors of 20 toxic and essential metals in the umbilical cord blood of Chinese newborns. Chemosphere. 2018. Nov;210:1167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millar JA, Forté CA. ColacinoLab / Farmwork_Citizenship_Pesticides: Code and data used to to compare pesticide exposure and bioactivity by farmwork history and US citizenship [Internet]. GitHub. 2023. Available from: https://github.com/ColacinoLab/Farmwork_Citizenship_Pesticides [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wickham H ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis [Internet]. 3rd ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. [cited 2023 Jan 9]. (Use R!). Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Susmann H. Package “RNHANES”: Facilitates analysis of CDC NHANES data [Internet]. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. 2016. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/RNHANES/RNHANES.pdf

- 39.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. ToxCast & Tox21 Summary Files from invitrodb_v3 [Internet]. Safer Chemicals Research | US EPA. 2020. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/exploring-toxcast-data

- 40.Sniegoski LT, Moody JR. Determination of serum and blood densities. Anal Chem. 1979;51(9):1577–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hocking TD. Package “WeightedROC”: Fast, weighted ROC curves [Internet]. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. 2020. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/WeightedROC/WeightedROC.pdf

- 42.Mason SJ, Graham NE. Areas beneath the relative operating characteristics (ROC) and relative operating levels (ROL) curves: Statistical significance and interpretation. Q J R Meteorol Soc. 2002;128(584):2145–66. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pérez-Maldonado IN, Trejo A, Ruepert C, Jovel RDC, Méndez MP, Ferrari M, et al. Assessment of DDT levels in selected environmental media and biological samples from Mexico and Central America. Chemosphere. 2010. Mar;78(10):1244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li BA. Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT): An unforgettable and powerful pesticide. J High Sch Sci [Internet]. 2022. [cited 2023 May 24];6(2). Available from: https://www.excli.de/vol17/Lushchak_08112018_proof.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibson JC, Marro L, Brandow D, Remedios L, Fisher M, Borghese MM, et al. Biomonitoring of DEET and DCBA in Canadian children following typical protective insect repellent use. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2023. Mar;248:114093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mills PK, Beaumont JJ, Nasseri K. Proportionate Mortality Among Current and Former Members of the United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO, in California 1973–2000. J Agromedicine. 2006. Jul 21;11(1):39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fry K, Power MC. Persistent organic pollutants and mortality in the United States, NHANES 1999–2011. Environ Health. 2017. Dec;16(1):105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohn BA, La Merrill M, Krigbaum NY, Yeh G, Park JS, Zimmermann L, et al. DDT Exposure in Utero and Breast Cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015. Aug;100(8):2865–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guadamuz JS, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Daviglus ML, Calip GS, Nutescu EA, Qato DM. Citizenship Status and the Prevalence, Treatment, and Control of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors Among Adults in the United States, 2011–2016. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020. Mar;13(3):e006215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chasens ER, Dinardo M, Imes CC, Morris JL, Braxter B, Yang K. Citizenship and health insurance status predict glycemic management: NHANES data 2007–2016. Prev Med 2020. Oct;139:106180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The NHANES and ToxCast datasets analysed during the current study are available from the CDC, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/, and the EPA, https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/exploring-toxcast-data.