Abstract

Long-range ribonucleic acid (RNA)–RNA interactions (RRI) are prevalent in positive-strand RNA viruses, including Beta-coronaviruses, and these take part in regulatory roles, including the regulation of sub-genomic RNA production rates. Crosslinking of interacting RNAs and short read-based deep sequencing of resulting RNA–RNA hybrids have shown that these long-range structures exist in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV)-2 on both genomic and sub-genomic levels and in dynamic topologies. Furthermore, co-evolution of coronaviruses with their hosts is navigated by genetic variations made possible by its large genome, high recombination frequency and a high mutation rate. SARS-CoV-2’s mutations are known to occur spontaneously during replication, and thousands of aggregate mutations have been reported since the emergence of the virus. Although many long-range RRIs have been experimentally identified using high-throughput methods for the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strain, evolutionary trajectory of these RRIs across variants, impact of mutations on RRIs and interaction of SARS-CoV-2 RNAs with the host have been largely open questions in the field. In this review, we summarize recent computational tools and experimental methods that have been enabling the mapping of RRIs in viral genomes, with a specific focus on SARS-CoV-2. We also present available informatics resources to navigate the RRI maps and shed light on the impact of mutations on the RRI space in viral genomes. Investigating the evolution of long-range RNA interactions and that of virus–host interactions can contribute to the understanding of new and emerging variants as well as aid in developing improved RNA therapeutics critical for combating future outbreaks.

Keywords: gene regulation, RNA structure, post-transcriptional control, RNA interactions, viral genomics, sub-genomic RNA, pseudoknot, SHAPE

Introduction

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses have emerged as one of the greatest threats for triggering pandemics in the recent years [1, 2]. SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19 pandemic, is a positive-stranded 30 kb RNA virus belonging to the Betacoronavirus genus (family Coronaviridae) [3–5]. This fast evolving virus has affected >500 million individuals and has caused >6 million deaths around the world (https://covid19.who.int/), causing a global health crisis. Other members of the Betacoronavirus family, including the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, are of special concern due to their fast-evolving nature and high transmission [6]. Several studies in the past have illustrated the interaction between viral RNA and host cellular components, which modulates the host response to infection [7–10]. Long-range RNA–RNA interactions (RRIs) are prevalent in the large, single-stranded RNA genomes of SARS-Co-V2 [11]. Recent study has experimentally mapped the long-range RRIs in the full-length SARS-CoV-2 genome and sub-genomic messenger RNAs (mRNAs) produced by discontinuous transcription [11]. These interactions take part in regulatory roles, including the regulation of sub-genomic RNA production rates and regulation of viral replication and transcription. Crosslinking of interacting RNAs and short read-based deep sequencing of resulting RNA–RNA hybrids have shown that these long-range structures exist in SARS-CoV-2 on both genomic and sub-genomic levels and in dynamic topologies [11]. Such RRIs enable the virus to engage with host RNAs, resulting in altered host response to viral infection. Furthermore, co-evolution of coronaviruses with their hosts is accompanied by genetic mutations made possible by its large genome and high recombination frequency (of up to 25% for the entire genome in vivo [12]) since SARS-CoV-2’s mutations can occur spontaneously during replication.

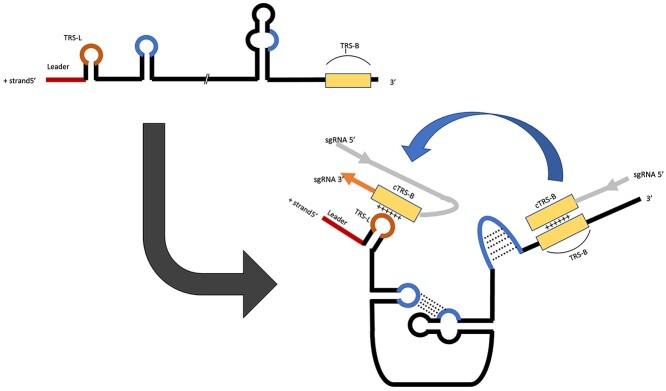

RNA–RNA interactions (RRIs) are ubiquitous across the kingdom of life. These types of interactions are essential in a variety of biological functions. In eukaryotic cells, RRIs play a significant role in the RNA function and regulation by taking part in the basic cellular activities, such as transcription, RNA processing, localization and translation [13]. For instance, intronic regions of precursor mRNAs are recognized by small nuclear RNAs during the splicing process [14]. Transfer RNAs interact with the mRNAs during the translation process [15, 16]. In addition, microRNA (miRNA) and 3′ UTR of an mRNA can bind in order to degrade the mRNA or inhibit its translation [17, 18]. RRIs are also involved in modification, where small nucleolar RNAs guide the modification of ribosomal RNAs [19, 20]. In viruses, in particular Coronaviruses, RRIs are involved in the process of discontinuous transcription, where the positive and negative RNA strands bind to facilitate template-switching, leading to sub-genomic mRNA synthesis [21]. The mechanism for discontinuous transcription (Figure 1) involves the transcription regulatory sequence leader (TRS-L), this sequence exists at the 5′ end of coronavirus genomes as well as immediately upstream of each transcriptional unit (TRS-B). The TRS-L acts as a cis-regulator of the transcription to produce specific sub-genomic RNAs, resulting in all mRNAs containing identical leader sequences at the 3′ end. This mechanism for discontinuous transcription is stabilized by RRIs, which can vary across species and genes. Sola et al. have proposed a detailed mechanism for the N-gene transcription in coronaviruses, which includes discontinuous transcription [22]. It is noteworthy that hybridization of RNA and DNA can also form structures in double-stranded DNA viruses. A good example is R-loop formation in Herpesviruses, which is an emerging player in various biological processes [23].

Figure 1.

Schematic showing a non-specific, simple overview of the mechanism for discontinuous transcription in coronaviruses. The beginning region colored in red and marked as leader indicates the leader sequence. The subsequent stem-loop indicates the leader transcription regulatory sequence leader (TRS-L). The rectangular yellow region indicates the body transcription regulatory sequence (TRS-B). The bulge regions marked in blue indicate the bases involved in stabilizing RRIs. RNA base pairs are indicated with dotted lines. Sub-genomic RNA is abbreviated as sgRNA. The orange region on the sgRNA is the newly transcribed RNA, with the light-gray region on the sgRNA having already been transcribed. ‘+’ symbols indicate the complementarity of the genomic RNA and sub-genomic RNA (positive and negative strands).

Although many long-range RRIs have been experimentally identified for the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strain, evolutionary trajectory of these RRIs across variants, impact of mutations on RRIs and interaction of SARS-CoV-2 RNAs with the host have not been extensively studied. Investigating the evolution of long-range RNA interactions, such as [24], as well as exploring the variant-specificity of such interactions [25], and that of virus–host interactions can contribute to understanding new and emerging variants as well as aid in developing improved RNA therapeutics that is critical for combating future outbreaks. Furthermore, insights into the computational and experimental methods to study RNA structure-based mechanisms that regulate the viral replication, discontinuous transcription and translation will provide a roadmap for the development of effective viral therapies. In this review, we summarize the computational and experimental methods that have been developed in the recent years to map the RRIs in viral genomes, with specific focus on SARS-CoV-2. We also present the databases available to navigate the RRI maps in SARS-CoV-2 genome, which will stand as a useful resource for viral researchers. We also shed light on the impact of mutations on the RRI space in viral genomes.

Computational methods for RRI mapping

Since the initial discovery of non-coding RNAs and their versatility, RNA target detection has been an important challenge to tackle [26, 27]. Many different tools have been developed to predict stable RRIs; most rely on dynamic programming and minimum-free energy (MFE) methods like secondary structure prediction tools. A general breakdown of these tools and their strategies, as well as what features impact prediction, are shown in Table 1. The chosen tools were found to fall into one of four groups: those that consider intermolecular interactions only, concatenation-based methods, accessibility-based methods and non-restrictive and not concatenation-based methods.

Table 1.

Computational tools and their strategies to predict stable RRIs

| Tool | Accessibility-based | Type of pairing considered | Suboptimal results | Alignment as input | Concatenation-based | SHAPE reactivity data | RNA-structure | Year of publication [reference] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IntaRNA | Yes | Intermolecular and intramolecular | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | 2008 [34] |

| RNAup | Yes | Intermolecular and intramolecular | No | No | No | No | Yes | 2006 [35] |

| RNAcofold | No | Intramolecular | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2006 [30] |

| pairfold | No | Intramolecular | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 2005 [31] |

| ractIP | No | Intermolecular and intramolecular | No | No | No | No | Yes | 2010 [38] |

| RNAplex-a | Yes | Intermolecular and intramolecular | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 2011 [36] |

| AccessFold | Yes | Intermolecular and intramolecular | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2016 [40] |

| bifold | No | Intermolecular and intramolecular | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2010 [29] |

| RNAduplex | No | Intermolecular | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2011 [28] |

| RNAaliduplex | No | Intermolecular | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 2011 [28] |

Many tools have been provided with updates since publication.

All the pieces of software highlighted in Table 1 incorporate the thermodynamic stability to predict structure, however, they have slightly different strategies. While all the listed tools consider intermolecular pairing in some way, some tools, like RNAduplex and RNAaliduplex [28], neglect intramolecular base pairing to speed up computation at the expense of accuracy, while most others, like bifold [29], consider it. This is to say that tools like RNAduplex will only predict the pairing between two RNA molecules without considering intramolecular pairings and thus ignoring how each RNA may fold independently. Also, concatenation-based methods, such as RNAcofold [30] and pairfold [31], involve combining the two interacting sequences and predicting a single secondary structure using tools, such as RNAfold [32], and thus only consider intramolecular interactions. The main disadvantage of concatenation methods is the inability to predict pseudoknots.

Another feature which differentiates RRI mapping tools is whether they consider the accessibility of the RNA when computing the MFE, which is considered more realistic [33], as in IntaRNA [34], RNAup [35] and RNAplex [36]. These tools utilize the McCaskill partition function algorithm [37] to predict the pairing probabilities of nucleotides at each position and thus the accessibility of each subsequent base-pair is affected by previous pairs. The incorporation of accessibility into these tools has significantly increased accuracy. IntaRNA and RNAplex can also be used for long-range target identification of RNAs, where it searches for the best match between two sequences and can be used for a transcriptome-wide target search.

Finally, RactIP [38] attempts to predict interactions, with very little restrictions and without using concatenation methods. The lack of restrictions greatly affects run-time performance, however, RactIP uses integer programming to allow for longer input sequences. Some of these tools, like RNAaliduplex (the alignment-based version of RNAduplex), use comparative or alignment-based methods as well. RNAplex can optionally accept alignments as inputs. Predicting RRIs with alignments can be useful in determining how conserved a particular RRI, or a binding site, is. It is also powerful for evaluating RRIs using covariation as evidence for the existence of a particular binding site [39]. The most recent of these listed tools, AccessFold, aimed to increase the prediction performance over other tools, specifically in the context of binding sites interrupted by unimolecular structures [40]. AccessFold first considers the structure of each RNA molecule prior to binding prediction and thus incorporates the accessibility/structure of each individual RNA into predicting interactions.

While all tools have their specific use cases, some do perform better than others on average. Lai and Meyer, in 2016, performed a comparison between many of these tools on experimentally validated bacterial small RNA–mRNA interactions and fungal small nucleolar RNA–ribosomalRNA interactions and found that accessibility-based approaches performed best, with IntaRNA consistently performing well and RNAplex following closely behind [41]. Subsequently, in 2017, Umu and Gardner performed another comparison between the general RRI mapping tools [42]. They constructed their dataset to include many types of RNA across several species to get a more generalized comparison to previous work. The eukaryotic dataset was constructed using many experimentally validated interactions between target RNAs or mRNAs and miRNAs, small RNAs and small nucleolar RNAs. A bacterial dataset was constructed from experimentally verified sRNA and mRNA targets. It was observed that IntaRNA, RNAplex and RNAup were performing consistently well across all RNA types. Based on these previous two benchmarking studies comparing various computational RRI prediction methods, each with different datasets, IntaRNA and RNAplex are likely to be the best first choice for general RRI mapping. Additionally, IntaRNA and RNAcofold can incorporate experimental Selective 2′-Hydroxyl Acylation analyzed by Primer Extension (SHAPE) reactivities to improve interaction mapping. Since the scope of this review is on general RRIs, tools developed and applicable specifically for certain types of RNAs, such as miRNA target prediction, are not covered. Some miRNA-specific tools include TargetScan [43], miRanda [44] and RNAhybrid [45].

Experimental methods for mapping RRIs

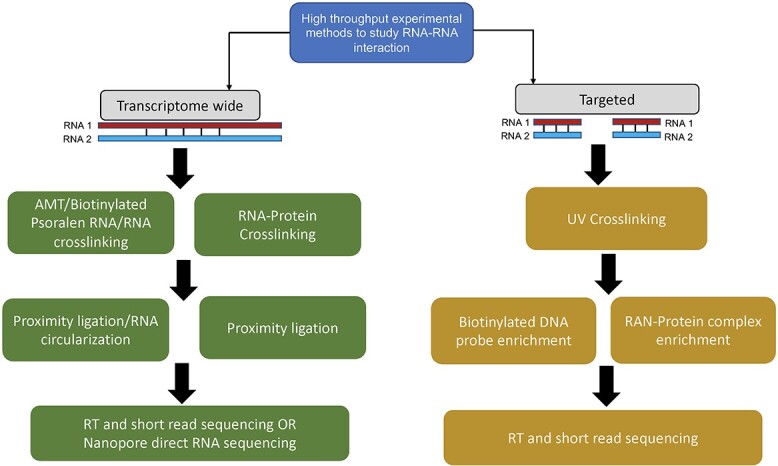

RRIs are important in many basic cellular activities, including transcription, RNA processing, localization and translation. RRIs can be generally classified into two groups: interactions mediated by proteins, or those effected by direct RNA base pairing. Hence, naturally based on the interaction’s methods used to study RRIs, they can be classified into two corresponding categories. The first category includes protein pull-down-dependent methods, such as CLASH, hiCLIP and MARIO [46–48]. The second category includes direct RRI detection methods, such as PARIS [49, 50], SPLASH [10, 51, 52] and LiGR-Seq [53]. All these methods can be grouped into three categories—including both conventional, focused biophysical and biochemical methods and recently developed large-scale sequencing-based techniques. Most of these methods use short read sequencing approach to identify the RNA molecules. Table 2 highlights several of the high-throughput methods that have been commonly employed for discovering RRIs in model systems in recent years. Figure 2 presents an overview of the specific experimental steps involved in mapping RRIs using transcriptome-wide and target-centric approaches.

Table 2.

High-throughput experimental methods used to study RRIs

| Method | Technique | Procedure | Samples | Sequencing | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIA-seq | Targeted | UV crosslinking Antisense DNA probe enrichment |

Human | cDNA short read | [61] |

| RAP | Targeted | UV crosslinking Antisense DNA probe enrichment |

Mouse | cDNA short read | [62] [63] |

| CLASH | Targeted | UV crosslinking RNA–protein enrichment Proximity ligation |

Escherichia coli, yeast, human | cDNA short read | [46] [47] [48] |

| COMRADES | Targeted/ transcriptome | Clickable Psoralen crosslinking DNA probe enrichment Biotinylated crosslink Proximity ligation Reverse crosslink |

SARS-CoV-2 virus | cDNA short read | [11] |

| PARIS | Transcriptome | AMT crosslinking Proteinase and Rnase digestion 2D-gel purification Proximity ligation Reverse crosslinking |

Human Mouse |

cDNA short read | [49] [50] |

| SPLASH | Transcriptome | Biotinylated Psoralen crosslinking Fragmentation Bead purification Proximity ligation |

E. coli, yeast, human, SARS-CoV-2 virus | cDNA short read | [10] [51] [52] |

| LIGR-seq | Transcriptome | AMT crosslinking RNA circularization Reverse crosslinking |

Human | cDNA short read | [53] |

| MARIO | Transcriptome | RNA–protein crosslinking Proximity ligation Biotin enrichment |

Mouse | cDNA short read | [64] |

| SHAPE-MaP | Transcriptome | NAI single-strand modification RT-induced mutations or drop off |

SARS-CoV-2 virus | cDNA short read | [10] |

| PORE-cupine | Transcriptome | NAI single-strand modification | SARS-CoV-2 virus | Direct RNA sequencing | [10] |

Figure 2.

Flowcharts summarizing the common experimental protocols employed for high-throughput mapping of RRIs across the entire transcriptome (left) and for specific RNA target regions of interest (right).

RNA viruses, such as coronaviruses, infect cells via RNA–RNA and RNA–protein interactions. Identification of RNA interactions between viral particles and those between virus and host transcriptome gives a bigger picture of the mode of action and help to identify the therapeutic targets. Many available protocols have been used to study RRIs in SARS-Cov2-infected cells. Yang et al. used the high-throughput RNA structure probing and direct RRI detection methods—SHAPE-MaP, PORE-cupine and SPLASH methods—to identify RNA interactions in WT and Δ382 SARS-CoV-2 genomes (see Table 2). SHAPE-MaP and PORE-cupine [10] used NAI single base-modifying chemical agent to introduce RNA modifications in unpaired bases to facilitate the identification of unstructured single-stranded RNA regions; following which, they used short read sequencing to map such mutations in SARS genome. In particular, SHAPE-MaP used mutations or rT drop off at modified bases from short read sequencing data to identify mutations. These mutations help track single bases. In contrast, PORE-cupine was coupled with the third-generation long read nanopore sequencing. Nanopore sequencing enables direct RNA sequencing without fragmentation. When modified bases pass through nanopores, the modification in mutated bases is recorded, and these modified signals are used to map mutations. Proximity ligation sequencing (SPLASH) method uses the RNA ligation enzyme to seal the nearby interacting RNA molecules together as one sequenced read, thereby enabling the discovery of the identifies of the interacting RNA molecules from long read sequencing data. Once ligated RNA molecules are sequenced, resulting reads are mapped to host and SARS genome. Biotinylated psoralen was used to crosslink pair-wise RNA interactions in infected cells to capture both intramolecular and intermolecular RRIs. Omer Ziv et al. developed the crosslinking of matched RNAs and deep sequencing (COMRADES) [11] for in-depth RNA conformation capture in living cells. In this high-throughput direct RRI detection protocol, virus-inoculated cells are crosslinked using clickable psoralen. Viral RNA is pulled down from the cell lysate using an array of biotinylated DNA probes, following which the digestion of the DNA probes and fragmentation of the RNA is performed. Biotin is attached to the crosslinked RNA duplexes via click chemistry, enabling pulling down crosslinked RNA using streptavidin beads. Half of the RNA duplexes are proximity-ligated, following reversal of the crosslinking to enable sequencing. The other half serves as a control in which the crosslink reversal proceeds the proximity ligation [11].

Databases for RRIS in RNA viruses

Host–protein interactions (HPI) characterize the interplay between the invading pathogen and the native host [54]. These interactions enable microbes or viruses to sustain themselves within the host organism on a cellular, molecular and organismal level to achieve their diverse functions [54]. Such HPI include protein–protein interactions (PPI), protein–RNA interactions (PRI) and RRIs. RRI between SARS-CoV-2 and human hosts have been described. Studies have reported interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and host miRNAs. These interactions have mostly been associated with host immune-related genes, depriving them of their functions [55, 56]. Of note, miR-374A-3p has been identified to be a target of the SARS-CoV-2 gene coding for the Spike protein and ORF1ab, which encodes for the 5′ viral replicase [57]. Also, interactions between the SARS-CoV-2 viral genome RNA Sequences and miR-219a-2-3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-378d, miR-29a-3p and miR-15b-5p have been identified and validated [58].

Due to the extensive number of interactions that have been identified between SARS-CoV-2 and host organisms, it is important to curate representative frameworks in form of databases, for the convenient exploration of these interactions, to enable further research on the development of effective treatments and vaccines. Several publicly available databases have been developed for the exploration of SARS-CoV-2’s PPI and PRI; however, there is a deficiency of databases catering to RRI data. Table 3 shows three publicly available databases and platforms containing viral RRI. Although they may not contain SARS-CoV-2 data currently, these resources could enable the understanding of RRI, as the data on SARS-CoV-2-host interactions continue to grow. It is anticipated that novel information emerging from studies on SARS-CoV-2 RRI, such as those discussed in the EXPERIMENTAL METHODS FOR RRI MAPPING section, would be available in these database resources in the near future to enable the integration of these interactions for studying viral interactomes.

Table 3.

Databases and platforms containing viral RRIs

| Databases | URL | Description |

|---|---|---|

| HPIDB v3.0 | https://hpidb.igbb.msstate.edu | Currently holds 69, 787 curated entries on the annotation and prediction of HPI, including PPI and RRI [65]. |

| IntaRNA v2.0 | http://rna.informatik.uni-freiburg.de/IntaRNA/Input.jsp;jsessionid=EB1F5FFAF1A8CEB2836E5761A31A3E3F | Designed specifically for the prediction of RRI among mRNA targets for non-coding RNAs but can also be used for other RRI [66]. |

| RNAInter v4.0 | http://www.rnainter.org | RNA–RNA interactome repository consisting of >47 million entries. It is grouped by organism as well as RNA types and separates the entries by the amount of experimental evidence for the interaction. Interactions are annotated with confidence sores [67]. |

| miRTarBase | https://mirtarbase.cuhk.edu.cn/∼miRTarBase/miRTarBase_2022/php/index.php | Experimentally validated database containing >300 000 miRNA-Target interactions curated manually from miRNA-related research [68]. |

| miRDB | http://www.mirdb.org | An online database for functional annotation and prediction of miRNA targets in human, mouse, rats, dogs and chicken. Users can also provide their own sequences to generate custom target predictions [69]. |

Impact of mutations on RRI plasticity

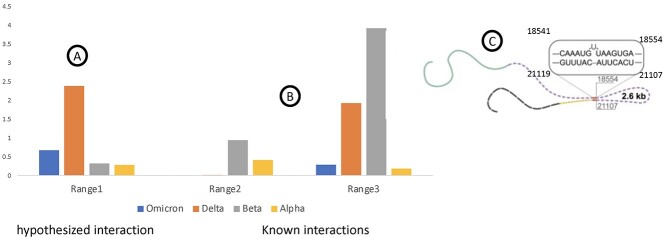

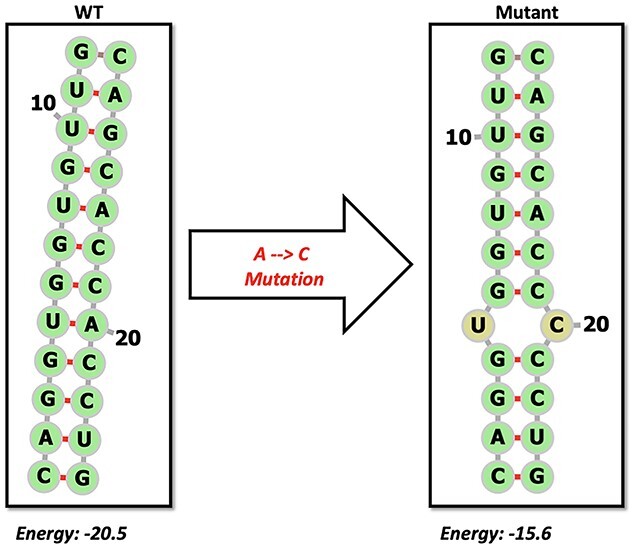

Mutations to RNA structures within the 5′ or 3′ UTR of RNA viruses have been shown to completely abolish RNA synthesis due to the functional importance of the TRS elements [59]. In 2018, a mutation to a discovered RRI specific to an Asian lineage of the Zika virus greatly affected the infectivity of the strain [60]. Hence, the rapid evolution of RNA viruses is likely to contribute to their potential impact on the RRI landscape. However, since most of the RRI are not reported and elucidated in RNA viruses, the relationship between the repertoire of naturally occurring mutations in a viral genome and their contribution to the altering of the structure and function of an RNA is poorly known. For instance, Figure 3 highlights an example of a 12-nucleotide RNA stem along which a hypothetical mutation is introduced, resulting in an increased overall free energy of the molecule, suggesting that the genetic variation across RNA structures not only impacts the structure of the molecule but can also alter the local/global stability of the molecule. Indeed, our own literature review combined with in silico predictions resulted in several RRI candidates in the SARS-Cov2 genome (Figure 4). In a pilot experiment, when evolutionary changes within the desired regions were investigated by considering mutations across a population of SARS-COV2 sequences, interesting observations were made. For three different long-range interactions, two from known [11] and one novel predicted interaction, mutations were investigated in comparison to the Wuhan reference sequence. Figure 4 illustrates the relative mutation rate for three such interacting regions highlighted across the three figure panels. As can be noted, mutation rate is different in a predicted interaction (A) compared to two other interactions derived from the literature (B). Values were normalized to mutations observed in the vicinity of each interacting interval. The interacting region depicted as Range3 derived from the literature is shown in (C). This region is a result of an RRI between the ORF1ab and upstream of the Spike gene. As shown, the Delta variant presents a high mutation in the first region (A) compared to others, while the Beta variants contain more mutations for a different long-range interaction (B). These observations indicate that the mutational load on functional RRI can have a significant impact and deserves a detailed understanding of the structure–function relationships since SARS-COV2 variants could result in differing RRIs due to altered genotypes.

Figure 3.

Schematic showing the impact of single point mutation on the structure and free energy of a 12-nucleotide long double-stranded RNA.

Figure 4.

Relative mutation rate of interacting regions within the population of sequences belonging to a specific variant. (A) Mutation rate for a hypothetical interaction (Range 1). (B) Mutation rate for two interacting regions from the literature [3]. (C) The schematic of the interacting region corresponding to Range 3, which was derived from the literature.

Conclusion

As summarized in this brief review, although an increasing number of studies in recent years, using both high-throughput as well as focused target-centric approaches, have reported RRIs across viral genomes, our understanding of their functional context and consequences is poorly described. Informatics resources to document and visualize RRI in viral genomes have also been very limited, further contributing to our lack of understanding about the importance of this interactome in studying host–pathogen dynamics. Hence, the time is ripe to not only explore the high-throughput generation of RRI across RNA viral genomes but also across variants and genotypes to study how RRI evolve with time and across variants as well as to dissect the functional consequences of these interactions to enable a comprehensive mechanistic and functional understanding of RRI across modal systems. Such an understanding would pave way for future therapeutic interventions since the RNA viruses are known to evolve rapidly, and the community’s ability to tap into RNA modalities is increasingly being appreciated as a therapeutic target for numerous beta coronaviruses.

Glossary

Sub-genomic RNA: Subgenomic RNAs have the same 3′ ends as genomic RNA but have deletions at the 5′ ends and are reported to occur in positive strand viruses.

Pseudoknots: Tertiary RNA structures which are formed when unpaired bases from a loop in a stem-loop pair with a single-stranded region elsewhere in the sequence.

SHAPE-seq: A protocol which stands for Selective 2’-Hydroxyl Acylation analyzed by Primer Extension and sequencing and is employed for mapping the secondary structure of RNA.

NAI: NAI stands for 2-methylnicotinic acid imidazolide and is one of the reagents used for performing SHAPE-seq.

rT, Reverse Transcription

Key Points

Long-range RRIs are prevalent in positive-strand RNA viruses, including Beta-coronaviruses, and take part in regulatory roles, including the regulation of sub-genomic RNA production rates.

Increasing number of recent high-throughput and target-centric approaches support and report an abundance of RRI in SARS-COV2, however, the functional understanding of these interactions is unclear.

Lack of informatics resources to navigate the currently available RRI maps across viral genomes remains a critical bottleneck.

Evolutionary trajectory of RRIs across variants, impact of mutations on RRIs and interaction of SARS-CoV-2 RNAs with the host have been open questions in the field.

Understanding the impact of the evolution of long-range RNA interactions and that of virus–host interactions across new and emerging variants can aid in developing improved RNA therapeutics critical for combating future outbreaks.

Mansi Srivastava obtained her doctoral degree in immunology from the Indian Institute of Technology, Indore, India, in 2019. Currently, she is a lecturer at the Department of Biology, Indiana University Bloomington. Her research interests are on the development of a high-throughput methods to map protein occupancy sites in transcriptome-wide manner through next-generation sequencing in cancer cells and mice tissues.

Matthew R. Dukeshire received a Bachelor of Science degree from the Purdue University in the field of biochemistry. He is currently studying for a master’s in bioinformatics at the Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis and is a member of the Janga research lab. His previous work revolves around RNA–RNA interactions, specifically in SARS-CoV-2.

Quoseena Mir is a PhD student in the microbiology and immunology program at the IU School of Medicine. Her current research interests are in dissecting the role of RNA-binding protein-mediated post-transcriptional networks in different cell lines and their effect on cell differentiation, with specific focus on T-cells.

Okiemute Beatrice Omoru completed her bachelor’s degree in medicine and surgery from the University of Lagos, Nigeria. She is a Master’s student in Janga lab and is currently researching on SARS-CoV2 interactions with the human genome. She is interested in cancer genomics and precision medicine.

Amirhossein Manzourolajdad obtained his PhD in bioinformatics from the University of Georgia followed by a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Institutes of Health. He is currently a visiting assistant professor of computer science at the Colgate University and his research interests are in RNA structural dynamics, riboswitches and evolution of viral RNAs.

Sarath Chandra Janga obtained his PhD from the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology & University of Cambridge in 2010. He is currently an associate professor of informatics at the School of Informatics, Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis and a faculty member of the Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics at the Indiana University School of Medicine. Sarath’s research interests include understanding the design principles and constraints imposed on gene regulatory systems within the broader field of computational and systems biology his lab works on.

Contributor Information

Mansi Srivastava, Department of BioHealth Informatics, School of Informatics and Computing, Indiana University Purdue University, 535 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA; Department of Biology, Indiana University, 1001 East 3rd St, Bloomington, Indiana 47405, USA.

Matthew R Dukeshire, Department of BioHealth Informatics, School of Informatics and Computing, Indiana University Purdue University, 535 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA.

Quoseena Mir, Department of BioHealth Informatics, School of Informatics and Computing, Indiana University Purdue University, 535 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA.

Okiemute Beatrice Omoru, Department of BioHealth Informatics, School of Informatics and Computing, Indiana University Purdue University, 535 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA.

Amirhossein Manzourolajdad, Department of BioHealth Informatics, School of Informatics and Computing, Indiana University Purdue University, 535 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA; Department of Computer Science, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY, USA.

Sarath Chandra Janga, Department of BioHealth Informatics, School of Informatics and Computing, Indiana University Purdue University, 535 West Michigan Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA; Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, Indiana University School of Medicine, Medical Research and Library Building, 975 West Walnut Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA; Centre for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, Indiana University School of Medicine, 5021 Health Information and Translational Sciences (HITS), 410 West 10th Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH under Award Number R01GM123314 (S.C.J.), National Science Foundation (NSF) grant #1908992 (S.C.J.) and IUPUI’s Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research COVID-19 Rapid Response Grant (S.C.J.). There are no grant numbers for funding received from within IU. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Alvarez-Munoz S, Upegui-Porras N, Gomez AP, Ramirez-Nieto G. Key factors that enable the pandemic potential of RNA viruses and inter-species transmission: a systematic review. Viruses 2021;13(4):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carrasco-Hernandez R, Jacome R, Lopez Vidal Y, et al. Are RNA viruses candidate agents for the next global pandemic? A review. ILAR J 2017;58:343–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahimi A, Mirzazadeh A, Tavakolpour S. Genetics and genomics of SARS-CoV-2: a review of the literature with the special focus on genetic diversity and SARS-CoV-2 genome detection. Genomics 2021;113:1221–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kames J, Holcomb DD, Kimchi O, et al. Sequence analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genome reveals features important for vaccine design. Sci Rep 2020;10:15643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brant AC, Tian W, Majerciak V, et al. SARS-CoV-2: from its discovery to genome structure, transcription, and replication. Cell Biosci 2021;11:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Wit E, van Doremalen N, Falzarano D, et al. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 2016;14:523–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 2020;583:459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Srivastava R, Daulatabad SV, Srivastava M, Janga SC. Role of SARS-CoV-2 in altering the RNA-binding protein and miRNA-directed post-transcriptional regulatory networks in humans. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Queiros-Reis L, Gomes da Silva P, Goncalves J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 virus-host interaction: currently available structures and implications of variant emergence on infectivity and immune response. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang SL, DeFalco L, Anderson DE, et al. Comprehensive mapping of SARS-CoV-2 interactions in vivo reveals functional virus-host interactions. Nat Commun 2021;12:5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ziv O, Price J, Shalamova L, et al. The short- and long-range RNA-RNA Interactome of SARS-CoV-2. Mol Cell 2020;80:1067, e1065–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patino-Galindo JA, Filip I, Rabadan R. Global patterns of recombination across human viruses. Mol Biol Evol 2021;38:2520–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guil S, Esteller M. RNA-RNA interactions in gene regulation: the coding and noncoding players. Trends Biochem Sci 2015;40:248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matlin AJ, Clark F, Smith CW. Understanding alternative splicing: towards a cellular code. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005;6:386–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ibba M, Soll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem 2000;69:617–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Selmer M, Dunham CM, Murphy FVT, et al. Structure of the 70S ribosome complexed with mRNA and tRNA. Science 2006;313:1935–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004;116:281–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet 2010;11:597–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kiss T. Small nucleolar RNAs: an abundant group of noncoding RNAs with diverse cellular functions. Cell 2002;109:145–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Watkins NJ, Bohnsack MT. The box C/D and H/ACA snoRNPs: key players in the modification, processing and the dynamic folding of ribosomal RNA. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2012;3:397–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sola I, Almazan F, Zuniga S, et al. Continuous and discontinuous RNA synthesis in coronaviruses. Annu Rev Virol 2015;2:265–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang D, Leibowitz JL. The structure and functions of coronavirus genomic 3′ and 5′ ends. Virus Res 2015;206:120–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wongsurawat T, Gupta A, Jenjaroenpun P, et al. R-loop-forming sequences analysis in thousands of viral genomes identify a new common element in herpesviruses. Sci Rep 2020;10:6389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Omoru OB, Pereira F, Janga SC, et al. A putative long-range RNA-RNA interaction between ORF8 and spike of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS One 2022;17:e0260331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dukeshire M, Schaeper D, Venkatesan P, Manzourolajdad A. Variant-specific analysis reveals a novel long-range RNA-RNA interaction in SARS-CoV-2 Orf1a. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 2004;431:350–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mattick JS. The genetic signatures of noncoding RNAs. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Honer Zu Siederdissen C et al. ViennaRNA package 2.0, Algorithms Mol Biol 2011;6:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reuter JS, Mathews DH. RNAstructure: software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2010;11:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bernhart SH, Tafer H, Muckstein U, et al. Partition function and base pairing probabilities of RNA heterodimers. Algorithms Mol Biol 2006;1:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andronescu M, Zhang ZC, Condon A. Secondary structure prediction of interacting RNA molecules. J Mol Biol 2005;345:987–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hofacker IL. Energy-directed RNA structure prediction. Methods Mol Biol 2014;1097:71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Richter AS, Backofen R. Accessibility and conservation: general features of bacterial small RNA-mRNA interactions? RNA Biol 2012;9:954–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Busch A, Richter AS, Backofen R. IntaRNA: efficient prediction of bacterial sRNA targets incorporating target site accessibility and seed regions. Bioinformatics 2008;24:2849–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Muckstein U, Tafer H, Hackermuller J, et al. Thermodynamics of RNA-RNA binding. Bioinformatics 2006;22:1177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tafer H, Amman F, Eggenhofer F, et al. Fast accessibility-based prediction of RNA-RNA interactions. Bioinformatics 2011;27:1934–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCaskill JS. The equilibrium partition function and base pair binding probabilities for RNA secondary structure. Biopolymers 1990;29:1105–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kato Y, Sato K, Hamada M, et al. RactIP: fast and accurate prediction of RNA-RNA interaction using integer programming. Bioinformatics 2010;26:i460–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hofacker IL, Fekete M, Stadler PF. Secondary structure prediction for aligned RNA sequences. J Mol Biol 2002;319:1059–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. DiChiacchio L, Sloma MF, Mathews DH. AccessFold: predicting RNA-RNA interactions with consideration for competing self-structure. Bioinformatics 2016;32:1033–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lai D, Meyer IM. A comprehensive comparison of general RNA-RNA interaction prediction methods. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Umu SU, Gardner PP. A comprehensive benchmark of RNA-RNA interaction prediction tools for all domains of life. Bioinformatics 2017;33:988–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 2015;4:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. John B, Sander C, Marks DS. Prediction of human microRNA targets. Methods Mol Biol 2006;342:101–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kruger J, Rehmsmeier M. RNAhybrid: microRNA target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic Acids Res 2006;34:W451–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kudla G, Granneman S, Hahn D, et al. Cross-linking, ligation, and sequencing of hybrids reveals RNA-RNA interactions in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:10010–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Helwak A, Kudla G, Dudnakova T, et al. Mapping the human miRNA interactome by CLASH reveals frequent noncanonical binding. Cell 2013;153:654–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Waters SA, McAteer SP, Kudla G, et al. Small RNA interactome of pathogenic E. coli revealed through crosslinking of RNase E. EMBO J 2017;36:374–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lu Z, Gong J, Zhang QC. PARIS: psoralen analysis of RNA interactions and structures with high throughput and resolution. Methods Mol Biol 2018;1649:59–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lu Z, Zhang QC, Lee B, et al. RNA duplex map in living cells reveals higher-order transcriptome structure. Cell 2016;165:1267–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Aw JG, Shen Y, Wilm A, et al. In vivo mapping of eukaryotic RNA Interactomes reveals principles of higher-order organization and regulation. Mol Cell 2016;62:603–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Aw JGA, Shen Y, Nagarajan N, Wan Y. Mapping RNA-RNA interactions globally using biotinylated psoralen. J Vis Exp 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sharma E, Sterne-Weiler T, O'Hanlon D, et al. Global mapping of human RNA-RNA interactions. Mol Cell 2016;62:618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Srivastava M, Hall D, Omoru OB, et al. Mutational landscape and interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with host cellular components. Microorganisms 2021;9:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Satyam R, Bhardwaj T, Goel S, et al. miRNAs in SARS-CoV 2: a spoke in the wheel of pathogenesis. Curr Pharm Des 2021;27:1628–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Khan MA, Sany MRU, Islam MS, et al. Epigenetic regulator miRNA pattern differences among SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and SARS-CoV-2 world-wide isolates delineated the mystery behind the epic pathogenicity and distinct clinical characteristics of pandemic COVID-19. Front Genet 2020;11:765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Graham RL, Sparks JS, Eckerle LD, et al. SARS coronavirus replicase proteins in pathogenesis. Virus Res 2008;133:88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Siniscalchi C, Di Palo A, Russo A, et al. Human MicroRNAs interacting with SARS-CoV-2 RNA sequences: computational analysis and experimental target validation. Front Genet 2021;12:678994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Alvarez DE, Lodeiro MF, Filomatori CV, et al. Structural and functional analysis of dengue virus RNA. Novartis Found Symp 2006;277:120–32 discussion 132-125, 251-123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Li P, Wei Y, Mei M, et al. Integrative analysis of Zika virus genome RNA structure reveals critical determinants of viral infectivity. Cell Host Microbe 2018;24:875, e875–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kretz M, Siprashvili Z, Chu C, et al. Control of somatic tissue differentiation by the long non-coding RNA TINCR. Nature 2013;493:231–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Engreitz JM, Sirokman K, McDonel P, et al. RNA-RNA interactions enable specific targeting of noncoding RNAs to nascent pre-mRNAs and chromatin sites. Cell 2014;159:188–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Engreitz J, Lander ES, Guttman M. RNA antisense purification (RAP) for mapping RNA interactions with chromatin. Methods Mol Biol 2015;1262:183–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nguyen TC, Cao X, Yu P, et al. Mapping RNA-RNA interactome and RNA structure in vivo by MARIO. Nat Commun 2016;7:12023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ammari MG, Gresham CR, McCarthy FM, et al. HPIDB 2.0: a curated database for host-pathogen interactions. Database (Oxford) 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fu JY, Medina JF, Funk CD, et al. Leukotriene A4, conversion to leukotriene B4 in human T-cell lines. Prostaglandins 1988;36:241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kang J, Tang Q, He J, et al. RNAInter v4.0: RNA interactome repository with redefined confidence scoring system and improved accessibility. Nucleic Acids Res 2022;50:D326–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Huang HY, Lin YC, Li J, et al. miRTarBase 2020: updates to the experimentally validated microRNA-target interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:D148–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wong N, Wang X. miRDB: an online resource for microRNA target prediction and functional annotations. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:D146–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]