Abstract

Murine monoclonal antibodies directed against proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 (low passage) were generated by the administration of antigen via the bite of borrelia-infected ticks. This strategy was employed as a mechanism to create antibodies against antigens presented by the natural route of tick transmission versus those presented by inoculation with cultured borreliae. One of the resultant antibodies reacted with a 17-kDa antigen from cultured B. burgdorferi, as seen by immunoblot analysis. This antibody was used to screen a B. burgdorferi genomic DNA lambda vector expression library, and an immunoreactive clone was isolated. DNA sequence analysis of this clone, containing a 2.7-kb insert, revealed several open reading frames. These open reading frames were found to be homologs of genes discovered as a multicopy gene family in the 297 strain of B. burgdorferi by Porcella et al. (S. F. Porcella, T. G. Popova, D. R. Akins, M. Li, J. D. Radolf, and M. V. Norgard, J. Bacteriol. 178:3293–3307, 1996). By selectively subcloning genes found in this insert into an Escherichia coli plasmid expression vector, the observation was made that the rev gene product was the protein reactive with the 17-kDa-specific monoclonal antibody. The rev gene product was found to be expressed in low-passage, but not in high-passage, B. burgdorferi B31. Correspondingly, the rev gene was not present in strain B31 genomic DNA from cultures that had been passaged >50 times. Serum samples from Lyme disease patients demonstrated an antibody response against the Rev protein. The generation of an anti-Rev response in Lyme disease patients, and in mice by tick bite inoculation, provides evidence that the Rev protein is expressed and immunogenic during the course of natural transmission and infection.

Lyme disease is caused by pathogenic species of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex (4, 16), which are transmitted to humans by the bite of Ixodes ticks, and results in a wide range of clinical manifestations if left untreated (11, 18, 31). The mechanisms involved in the spread and dissemination of the organism to various tissues and organ systems of the host are not well defined; however, studies to identify potential virulence factors responsible for transmission and infection have centered on several outer surface membrane-associated proteins (3, 10, 17, 19, 21, 24). The genes encoding these proteins have been localized to extrachromosomal plasmids (2, 25), which, along with a linear chromosome (8), make up the B. burgdorferi genome. Although a correlation has been made between plasmid loss caused by prolonged culture passage and subsequent loss of the organism’s infectivity (15, 22, 27, 29, 35), there has not been a direct link established to any gene products responsible for this phenomenon.

When grown in culture in vitro, B. burgdorferi differs phenotypically from its state associated with the tick. Some genes that are expressed only in the mammalian host following transmission, and that are not seen in medium-cultured borrelia, have been described (1, 7, 9, 20, 33, 34). Also, the genes expressing outer surface protein A (OspA) and OspC have been shown to be regulated by factors involved during tick feeding (28). Therefore, in studying factors that may be involved in mechanisms of the infectious process, it is important to recognize the differences in borrelia protein expression between the two environments.

This report involves one of several monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that were developed by tick bite inoculation of B. burgdorferi as the primary route of antigen administration. Antibodies generated by this method may recognize antigens that are essential to the transmission and dissemination of B. burgdorferi. When one of the antibodies was used as an immunoreactive probe against a phage lambda expression library of B. burgdorferi B31 genes, its specificity was determined to be against a gene product termed Rev. The rev gene has been described as part of a plasmid-encoded, multicopy gene family in B. burgdorferi 297 (designated the 2.9 locus) which, because of its complexity, has been postulated to play a role in facilitating the organism’s survival in diverse environments (23). (The term Rev was used simply to describe the gene’s reverse strand orientation in comparison with adjacent genes.) This paper reports the molecular characterization of the B31 strain rev gene, as well as the flanking genes and regions, and their comparison to the 2.9 locus genes of strain 297. Additionally, the presence and expression of the rev gene in various B. burgdorferi strains with varied in vitro culture passage histories were examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Borrelia strains.

B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31 (low passage, <10 passages; high passage, >50 passages) was provided by A. Barbour (University of California, Irvine). Strains N40 and HB19 were obtained from J. Leong (University of Massachusetts), and strain 297 was obtained from W. Probert (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Fort Collins, Colo.). Low passage for these strains was defined as <10 passages, and high-passage numbers were unknown. Borreliae were grown in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelley modified medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) supplemented with 6% rabbit serum (PelFreeze, Rogers, Ark.) at 34°C until cell growth reached approximately 107 to 108 organisms/ml, after which the cell pellet was collected, washed, and frozen at −20°C until needed. B31-infected Ixodes scapularis was provided by J. Piesman (CDC).

Production of anti-B. burgdorferi MAbs.

B. burgdorferi-infected nymphal ticks were allowed to feed on female BALB/cByJ mice (8 to 12 weeks old). Infection of mice with B. burgdorferi was confirmed by positive cultures derived from ear biopsy specimens (30). Mice were reinfested with B. burgdorferi-infected ticks 1 month later. At the end of this immunization schedule, serum samples were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and the mouse with the highest titer was selected for hybridoma production. Three days before the cell fusion procedure, 105 low-passage strain B31 organisms (passage 1, cultured from ticks) were injected intravenously. Spleen cells were harvested and fused with cP3×63–Ag8.653 myeloma cells by use of polyethylene glycol 1000. The spleen cell/myeloma cell ratio was approximately 5:1. Fused cells were selected by using medium containing hypoxanthine-aminopterin-thymidine. Wells were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent-assay and Western blotting with low-passage B. burgdorferi B31 as the antigen. Cells from positive wells were expanded and cloned by limited dilution. The antibody specific for the Rev protein was designated YM.17. The isotype was determined to be immunoglobulin G2A (IgG2a) by using an immunoglobulin typing kit (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.).

B. burgdorferi genomic library.

The B. burgdorferi genomic library was generated by EcoRI “star” digestion of B. burgdorferi genomic DNA and ligated into the Lambda-Zap(II) cloning vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) as previously described (12). The lambda library was plated onto Escherichia coli XLI Blue MRF′ (Stratagene), and plaques were immunologically screened with MAb YM.17 according to standard procedures; these are described in a separate study (13).

DNA procedures and analysis.

Lambda phage vectors containing cloned DNA inserts were converted to pBluescript phagemids by the in vivo excision method, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Stratagene). Recombinant plasmid isolation from E. coli was performed by using the QIAprep-spin Plasmid kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). DNA sequencing was performed with the Taq DyeDeoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.). Sequencing reactions were run and analyzed by the automated sequencing apparatus, model 373A (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). DNA sequences were computer analyzed with Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis.).

Southern transfer and hybridization procedures, probe generation, and detection have been described in detail previously (13). Briefly, total genomic DNA was fractionated on a 0.35% Tris-acetate-EDTA agarose gel. Following electrophoresis, the DNA was transferred to Nytran membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.). Probes were generated and detected according to the manufacturer’s directions by using an ECL Probe-Amp kit (Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England). PCR conditions for rev gene probe generation are detailed below. Hybridization conditions were 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 0.5% blocking agent (Amersham), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 5% dextran sulfate overnight at 60°C. Blots were washed three times for 10 min each time with a stringency of 0.5× SSC at 60°C.

PCR subcloning.

Coding sequence regions of selected genes were amplified by PCR and subcloned into plasmid expression vectors as follows. PCR primers for the rev gene were Rev-F1 (5′ AAAGCATATGTAGAAGAAAAG 3′) and Rev-B1 (5′ TTAGTGCCCTCTTCGAGGAAC 3′), where Rev-F1 is sequence from the 5′ end of the gene, starting just past the putative signal peptide, and Rev-B1 is sequence from the end of the coding sequence. PCR primers for the lipoprotein gene (LP) were LP-F1 (5′ ATGAAAATCATCAACATATTA 3′) and LP-B1 (5′ TTAGGACCCATTGCCGCAGGT 3′) and were derived from the beginning and end of the coding sequence, respectively. B1 primers for both genes were from the inverse complement of the coding sequence. The fragments were amplified from the original cloned insert in phagemid pBluescript (Stratagene) under the following conditions: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.001% gelatin, 200 μM (each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 1 μM each primer, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (AmpliTaq; Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.). Amplification was performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9600 thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus), with the parameters of 94°C for 30 s, 48°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min, for 35 cycles. The amplified gene fragments were ligated into the expression vector pSCREEN-1b(+) (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer’s directions. The constructs produced a recombinant fusion protein when expressed in E. coli Novablue (DE3) (Novagen).

Recombinant gene expression and Western blot analysis.

Cultures of E. coli containing the rev or LP gene inserted in the expression vector pSCREEN were begun by using a single transformant colony as the inoculum. The cells were grown in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 250 μg of carbenicillin/ml at 37°C until growth had progressed to mid-log phase. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to the culture to a concentration of 0.5 mM to induce expression of the fusion protein. The culture was allowed to incubate further for about 2 h; then the cells were pelleted by centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was frozen until ready for use. To obtain expression of recombinant protein, it was critical to induce the primary culture started from a transformant colony. A primary culture grown to saturation, and subsequently used as a starter inoculum for a new culture, did not produce recombinant protein. Expression of recombinant protein was poor or nonexistent when an overnight culture was used to start a fresh subculture, even when antibiotic pressure was consistent. E. coli whole-cell lysates expressing the recombinant protein, and lysates grown from cells containing plasmid only, were subjected to Western blot analysis according to standard procedures and have been described (13). An ascites preparation of MAb YM.17 was used at a dilution of 1:1,000.

Serum samples from Lyme disease patients were from the CDC National Lyme Disease Reference Serobank. Samples were used in immunoblots according to standard Western blot procedures. B. burgdorferi lysates were electrophoresed in 15% acrylamide gels, and E. coli recombinant Rev lysates were electrophoresed in 10% gels. The serum samples were reacted against the recombinant antigen at a 1:1,000 dilution and against the B. burgdorferi lysate antigen at a 1:500 dilution. Detection for both IgG and IgM antibodies was performed.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession no. for the B31 “2.9-like” locus is AF000270. The 297 strain loci are deposited under accession no. U45421 through U45427.

RESULTS

Gene isolation with MAb YM.17.

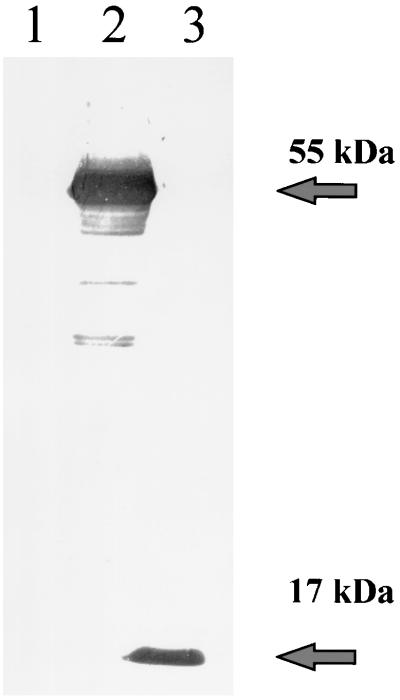

The specificity of MAb YM.17 was determined by Western blot analysis against a whole-cell lysate of low-passage B. burgdorferi B31. The immunoblot showed that MAb YM.17 was reactive against a protein with a molecular mass of approximately 16 to 17 kDa (Fig. 1, lane 3). The MAb was used to immunologically screen a lambda expression library of B. burgdorferi B31 genomic DNA in order to isolate the gene encoding the YM.17-reactive protein. Two weakly reactive plaques, with a signal slightly stronger than background, were chosen for further analysis.

FIG. 1.

Western blot showing reactivities to MAb YM.17. Lanes: 1, E. coli containing pSCREEN plasmid vector with no insert; 2, E. coli containing pSCREEN plasmid vector with the rev gene; 3, low-passage B. burgdorferi B31 lysate. Arrows indicate the approximate molecular sizes of native Rev (17 kDa) and the recombinant Rev fusion product (55 kDa).

These clones were isolated, plaque purified, and cultured to produce E. coli cell lysates as described in Materials and Methods. The lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with MAb YM.17 so that the size of the recombinant product could be observed. The recombinant lysate produced a very weak or negative band upon colorimetric detection of the immunoblot. Only by development with a more sensitive chemiluminescent assay was a specific product of approximately 16 to 17 kDa detected in the recombinant lysate samples (data not shown). Plasmid miniprep analysis showed that the insert size of this clone was approximately 2.7 kb. Therefore, it was probable that the gene was localized in the interior of the insert, where gene expression was not driven by the plasmid vector’s lacZ promoter, but rather by the native borrelia promoter, which produced low, barely detectable amounts of expressed gene product.

In order to determine the location and number of open reading frames (ORFs) to potentiate a 16- to 17-kDa gene product, the DNA of the entire cloned insert was sequenced. The sequencing results revealed several ORFs on both strands along the length of the insert, all potential candidates to encode the YM.17-specific protein. A search of the GenBank database identified these ORFs as homologs of multicopy genes found in several loci (termed the 2.9 locus) in B. burgdorferi 297 and described by Porcella et al. (23).

Description of the B31 strain 2.9-like locus genes.

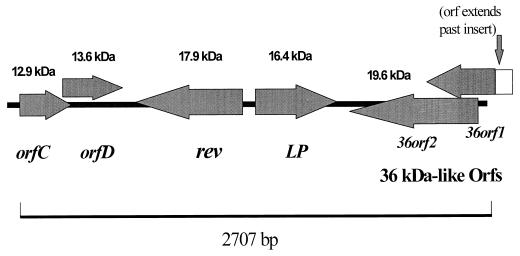

A diagram of the B31 insert containing the 2.9-like locus is shown in Fig. 2. Although very similar to the loci described for strain 297, this B31 locus was distinct in its gene order and arrangement from any single 2.9 locus. Also, the DNA sequences for the individual genes in the B31 clone were different from those of the corresponding genes in strain 297.

FIG. 2.

Diagram of the cloned insert containing the B31 2.9-like locus. Arrows represent genes and directions of transcription. The approximate molecular mass of the encoded protein is given above each gene.

The 5′ end of the insert began with the orfC gene, followed by the orfD gene. Downstream of orfD, on the opposite strand, lay the rev gene, followed by the LP gene back on the positive strand. At the end of the insert, on the negative strand, were two overlapping ORFs, one of which had homology to the 36kDa gene from the 2.9-5 locus of strain 297 (23) (Fig. 2).

The orfC coding region was 333 bp, encoding a protein of 111 amino acids with an estimated molecular mass of 12.9 kDa. Alignments of the B31 OrfC amino acid sequence against the OrfC amino acid sequences reported for strain 297 showed identity values from 94.6 to 81.5%. The orfD coding sequence overlapped slightly with that of the orfC, which was also seen in the strain 297 loci. The orfD coding region consisted of 351 bp, encoding a protein of 117 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 13.6 kDa. Identity alignments against the OrfD amino acid sequences of the strain 297 loci indicated a high degree of conservation, with a range from 94.0 to 91.5%. Not present on this cloned insert, but identified in the strain 297 2.9 loci, were ORFs A and B, directly upstream of ORFs C and D (23). Recently, ORFs A and B for strain B31 have been described as encoding proteins with hemolytic activity against erythrocytes and have been termed blyA and blyB, respectively (14).

The lipoprotein ORF was 444 bp, encoding a protein of 148 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 16.4 kDa. When it was compared to the lipoproteins of strain 297, substantial homology was seen, although less than that with the orfC and orfD genes. The B31 lipoprotein fit into the class 2 category, as defined for the strain 297 lipoproteins (23). The seven 2.9 lipoproteins in strain 297 diverged into two distinct classes after the first 50 amino acids. The amino acid identities of the B31 lipoprotein with the three class 2 lipoproteins of strain 297 were 75.9, 77.1, and 70.4%. Like the sequences of the products of the LP genes from strain 297, the B31 lipoprotein amino acid sequence contained the L-N-S-C signal peptidase II motif for lipoprotein processing and modification.

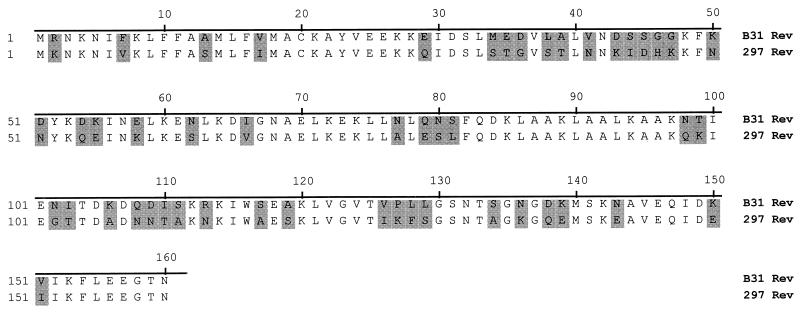

Between the orfD and LP genes, on the opposite strand, was the rev gene. It was seen in only one of the described strain 297 loci, 2.9-7. The B31 rev gene was 480 bp and encoded a polypeptide of 160 amino acids with an estimated molecular mass of 17.9 kDa. The B31 rev coding sequence contained the same number of amino acids as its strain 297 counterpart, although the amino acid identity between the two was only 68.8% (Fig. 3), and the nucleotide alignment showed 74.5% agreement. As described for the strain 297 rev, the B31 rev contained a putative leader peptide with a signal peptidase I cleavage site. Also identified for this gene were putative ribosome binding, −10, and −35 promoter sites, and inverted repeats serving as a transcription termination site. Protein sequence analysis revealed a secondary structure dominated by alpha-helical regions. The protein was composed of several hydrophilic regions, except for the hydrophobic amino-terminal end characteristic of a membrane-anchoring domain.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of the Rev proteins for B. burgdorferi B31 and 297. Differing amino acid residues are shaded.

An interesting feature of the B31 locus was the presence of two overlapping ORFs downstream and on the opposite strand from the LP gene. One of the ORFs has some similarity to a gene found in locus 2.9-5 of strain 297 which encoded a 36-kDa polypeptide and was designated 36kDa. The B31 ORFs were termed 36orf1 and 36orf2 (Fig. 2). A partial coding sequence is shown for 36orf1, as the 5′ end of the gene extends beyond the cloned insert. The 36orf2 gene was 498 bp, encoding a protein of 166 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 19.6 kDa. The homology of B31 36-Orf1 to the 297 36-kDa protein was limited to just certain stretches of the amino acid sequence, with large gaps in the alignment, but these stretches had a 72.7% identity to the 297 sequence. The B31 36-Orf2 amino acid sequence showed slight similarity to the 297 36-kDa amino acid sequence, with 25.1% identity.

Rev expression and reactivity with MAb YM.17.

To identify which gene encoded the protein reactive with MAb YM.17, subclones containing only a selected ORF, in which the individual expressed product could be tested by immunoblotting, were constructed. The LP gene seemed a logical candidate, but the expressed recombinant product demonstrated no reactivity to MAb YM.17 (data not shown). The next gene subcloned for expression was the rev gene. The recombinant Rev protein reacted strongly in a Western blot with MAb YM.17, thus demonstrating that YM.17 was specific to Rev (Fig. 1, lane 2). The large size of the recombinant reflects its expression as a 55-kDa fusion protein in this system.

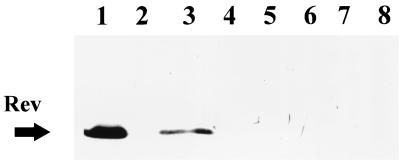

MAb YM.17 was immunoblotted against lysates of low- and high-passage cultures of B. burgdorferi strains. B31 low-passage cultured organisms showed the Rev 17-kDa reactive band (Fig. 4, lane 1). However, the Rev antigen was absent in high-passage B31 lysate (Fig. 4, lane 2). Figure 4 also shows no MAb YM.17 reactivity with lysates of high-passage cultures of strains HB19, 297, and N40. A weakly reactive band was seen in low-passage HB19 lysate (Fig. 4, lane 3), but no immunologic cross-reactivity was seen with MAb YM.17 against the Rev protein in strains 297 and N40.

FIG. 4.

Western blot of B. burgdorferi lysates against MAb YM.17. Lanes: 1, low-passage B31; 2, high-passage B31; 3, low-passage HB19; 4, high-passage HB19; 5, low-passage 297; 6, high-passage 297; 7, low-passage N40; 8, high-passage N40. YM.17 was used at a dilution of 1:1,000.

DNA hybridizations.

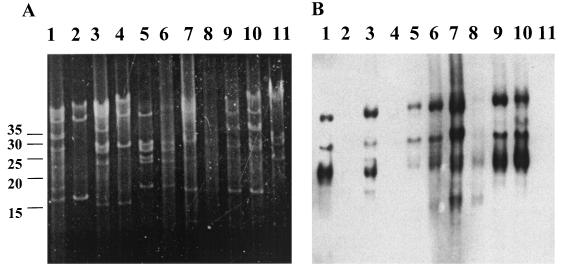

To determine the presence and general genomic location of the rev gene in total DNA preparations of B. burgdorferi strains, Southern blot analysis was performed. Figure 5A shows the plasmid profiles of DNA purified from low- and high-passage cultures of various strains of B. burgdorferi. Following hybridization, the rev gene was detected in the low-passage B31 DNA, but not in the high-passage B31 DNA (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 and 2). Accordingly, low-passage HB19 DNA hybridized with the rev gene probe, but high-passage HB19 DNA did not (Fig. 5B, lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, the rev gene was present in both low- and high-passage DNAs of the 297 and N40 strains (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 and 6 and lanes 7 and 8, respectively). To further explore this observation of rev association in low- versus high-passage genomes, DNA was isolated from strain B31 cultures with known in vitro culture passage histories and was probed with rev. The rev gene was present in both passage-3 and passage-26 genomes (Fig. 5B, lanes 9 and 10). Therefore, one explanation for the results seen in the Southern blot is that the plasmid harboring the rev gene is lost upon extremely prolonged culture passage, i.e., more than 26 passages in this case. The numbers of passages for the HB19, 297, and N40 samples were unknown, but the B31 had been passaged more than 50 times. It is possible that the HB19 had also been passaged many times, while the 297 and N40 were passaged relatively fewer times and thus retained the rev-containing plasmid.

FIG. 5.

Southern blot of total genomic DNA of B. burgdorferi strains hybridized against rev gene probe. (A) Ethidium bromide stain of DNA in 0.35% agarose; (B) Southern blot of gel in panel A probed with rev. Lanes: 1, low-passage B31; 2, high-passage B31; 3, low-passage HB19; 4, high-passage HB19; 5, low-passage 297; 6, high-passage 297; 7, low-passage N40; 8, high-passage N40; 9, cloned strain of B31 in lane 1, passage 3; 10, cloned strain of B31 in lane 1, passage 26; 11, B. hermsii. Linear DNA size markers in kilobases are shown to the left of panel A.

The Southern blot also demonstrated the plasmid location of the rev gene. The hybridizing bands in Fig. 5B were consistent with the various forms of a supercoiled 30- to 32-kb plasmid (6, 32), which has been described as the location for both the 2.9 locus genes in strain 297 (23) and the blyA and blyB genes in strain B31 (14). It has not yet been determined whether the assorted hybridizing bands were indicative of multiple copies of the rev gene, supercoiled forms of the plasmid, or a combination of both. B. hermsii genomic DNA was included in the Southern blot as a control, and no rev-hybridizing bands were observed in it (Fig. 5B, lane 11).

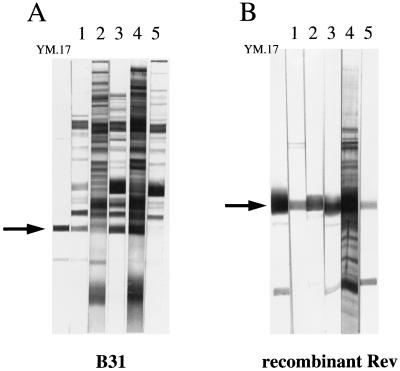

Serological reactivity to Rev protein.

Serum samples from Lyme disease patients were assayed for antibody reactivity to the Rev protein by Western blotting. The individual samples had been obtained various times after the onset of illness was assessed in these patients. Some samples showed prominent seroreactivity against the Rev protein when they were blotted against B. burgdorferi B31 lysates. These samples had been taken 90 days or less from the onset of disease, and the representative blots are shown in Fig. 6A. Not all serum drawn from patients diagnosed with early Lyme disease exhibited anti-Rev activity, and a more detailed serological survey involving Rev is in progress. The blots in Fig. 6 show IgG specificity, although IgM responses were also seen (data not shown). The samples were also blotted against recombinant Rev protein expressed in E. coli lysates and were positive (Fig. 6B). These results demonstrate that (i) humans develop an antibody response against the Rev protein as a result of infection and (ii) an antibody with reactivity directed against the B. burgdorferi Rev antigen is also reactive to the recombinant form of the protein.

FIG. 6.

Western blot reactivities of serum samples from human Lyme disease patients to Rev antigen. (A) Low-passage B31 as substrate antigen; (B) E. coli lysate expressing recombinant Rev as substrate antigen. Lanes 1 to 5 represent five human serum samples and are the same in panels A and B. Lane YM.17 shows the MAb specific to Rev serving as a marker. Arrows indicate the locations of the Rev antigens.

DISCUSSION

MAbs against B. burgdorferi antigens were generated in mice by the bite of borrelia-infected ticks, which served as the primary and first-booster injections. This method provided for the same manner of presentation of borrelia antigens to the host’s immune system as is seen in natural infections. Therefore, antibody production presumably represents those antigens processed upon transmission and infection. An important distinction between culture-grown, needle-inoculated organisms and tick-transmitted, host-adapted borreliae is that the latter express proteins not seen in cultured borreliae and that they differentially express proteins during tick feeding (1, 7, 9, 20, 28, 33, 34). An antibody, YM.17, generated by this method was found to be specific to a 17-kDa antigen, termed Rev, which apparently is expressed in, or present on, infectious B. burgdorferi cells. Rev, however, is also expressed in cultured low-passage infectious B. burgdorferi and therefore is not selectively expressed in vivo during host transmission. To our knowledge, this is the first description of a MAb generated by this tick-bite inoculation method, in which the corresponding gene product has been identified and molecularly characterized.

The B31 2.9-like locus is the counterpart of a multicopy locus consisting of a tandemly arrayed gene family in strain 297 described by Porcella et al. (23). This group demonstrated that there were at least seven loci containing similar gene copies of several ORFs, which they termed orfA through orfD, rep+, rep−, and LP. However, of these seven loci, only one (2.9-7) contained the rev gene. Their study showed that the 297 rev gene probe hybridized with a single restriction digest fragment in strain 297 but failed to hybridize with any fragments in strain B31. This result could have been due to probe mismatching, since the 297 rev oligomer probe differed from the B31 sequence by 2 bases. It is also possible that the plasmid harboring rev was missing from these investigators’ B31 isolate or DNA preparation, or both.

As seen with the 297 strain rev, the B31 rev gene had a characteristic leader signal peptide and the protein was hydrophilic, which indicates a potential outer membrane surface location. Even though it is flanked by adjacent genes, rev resides on the opposite DNA strand from these genes, and so apparently is transcribed by its own promoter. Sequences resembling consensus ribosome binding, −10, and −35 promoter regions were identified upstream of the B31 and 297 rev coding sequences.

Immunoblotting analysis with MAb YM.17 showed that the 17-kDa Rev protein was present in cultured low-passage B31 spirochetes but was not expressed in culture in high-passage B31. Low-passage HB19 expressed a Rev protein that was reactive to MAb YM.17, but the signal was weaker than that seen with B31, which may be due to heterogeneity between the two proteins or to differences in the protein expression level. No cross-immunoreactivity to Rev with MAb YM.17 was seen in the 297 and N40 strains. Since the amino acid alignment of the B31 and 297 Rev proteins showed only about 69% identity, the reactive epitope to MAb YM.17 probably lies in a less-conserved region. Either the same explanation holds for N40, or N40 does not express a Rev protein. None of the high-passage cultured organisms were recognized by MAb YM.17. However, Southern blot analysis showed that the rev gene was present in both low- and high-passage 297 and N40. Because the same cultures were used to isolate the protein and DNA used for the Western and Southern blots, respectively, the most logical explanation is that Rev is probably expressed by these two strains but is not cross-reactive with MAb YM.17. The lack of anti-Rev reactivity with high-passage B31, however, is explained by the loss of the rev gene, as seen in the Southern blot. A question remained as to why the rev gene was absent in high-passage B31 but not in 297 or N40. It was known that the high-passage B31 had been passaged in culture over a period of years, probably more than 100 times. Perhaps the high-passage 297 and N40 had not undergone such an extensive history of in vitro cultivation and thus had not yet lost the gene. To address this observation, a population from the low-passage B31 was passaged in culture, and cells were saved from selected passages for DNA and protein purification. Southern blot analysis of passage 26 of this B31 population showed that the rev gene was still present, even though this was considered high-passage B31. Passage-26 organisms expressed Rev, as seen by Western blotting (data not shown), but by inoculation of organisms from passage 26 into mice, it was determined that they were noninfectious (23a). Therefore, it was concluded that, in this case, rev may still be expressed in culture-passaged cells that have lost infectivity.

It has been well documented that B. burgdorferi undergoes changes in protein expression, with a concomitant loss of plasmids, during continuous passages in in vitro culture (2, 5, 15, 22, 26, 27, 35). Generally, at some point during prolonged culture passage, depending on the strain, the borreliae become noninfectious. There are only a few examples of characterized genes which reside on plasmids which are lost during prolonged cultivation, but they have not consistently been shown to be associated with the infectivity phenotype. The ospD gene, on a 38-kb linear plasmid (21), and the eppA gene, on a 9-kb circular plasmid (7), are two such cases. Also, Zhang et al. have recently associated the 28-kb linear plasmid-encoded vls locus to mainly high-infectivity-phenotype clones (36). Other groups have investigated and identified by molecular size some proteins associated with infectious low-passage organisms, but these have yet to be molecularly characterized (5, 22, 35). Xu et al. have proposed a link between a 24.7-kb or equivalent linear plasmid and infectivity with the three genospecies of Lyme disease borreliae, but as yet they have not characterized gene products encoded from this plasmid (35).

The results from this study demonstrate that rev is a plasmid-residing gene that is lost upon prolonged in vitro culture passage in strain B31. A correlation between the organism’s loss of infectivity and loss of rev and/or the plasmid on which it is located remains to be elucidated. However, the one example (B31, passage 26) that was examined in this study appears to demonstrate that the presence of rev is not directly associated with an infectivity phenotype. Further studies are needed to address whether rev is expressed in other noninfectious isolates of various strains of B. burgdorferi, and thus whether there may be a correlation between rev, or any of the 2.9 locus genes, and the pathogenicity of the organism.

A panel of serum samples from patients with confirmed cases of Lyme disease was used to survey seroreactivity against the Rev antigen. In this preliminary screening, it was found that some samples had a pronounced antibody response against Rev when they were blotted against strain B31 lysate. Representative samples showing this reactivity are shown in Fig. 6. This clearly demonstrates that Rev is recognized during human infection. Generally, serum samples drawn from patients 3 months or less from the onset of illness showed the strongest reactivity, although not all early Lyme samples exhibited anti-Rev activity by Western blotting. More extensive serological surveys are required to determine sensitivities and specificities of the humoral response to this antigen in patients at differing stages of Lyme disease. The sera with an antibody response to the borrelia Rev also reacted with the recombinant Rev, as seen in Fig. 6. Therefore, the Rev protein may have promise as a diagnostic antigen for Lyme disease serology.

In conclusion, a MAb was made by a technique which involved borrelia inoculation into the host mouse by way of tick bite, representing the route of transmission of the organism in nature. The MAb was specific to the Rev protein, an antigen that was recognized by the antibody response of serum from human Lyme disease patients. The rev gene was associated with a multicopy locus gene family consisting of lipoprotein and hemolysin genes, as well as other genes of unknown function. It should prove interesting to further explore the potential role of these genes in the infectious process and pathogenesis of B. burgdorferi, particularly in the context of tick-host interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the contributions of the following: J. Boonjakuakul for help in plasmid isolations, S. Sviat for Borrelia culturing assistance, R. Tsuchiya for DNA sequencing support, and B. J. B. Johnson and W. Probert for their work in characterizing strains and for their critiques and helpful discussions regarding the manuscript. Special thanks are due to S. Porcella for sharing his thoughts and providing unique insight to this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins D R, Porcella S F, Popova T G, Shevchenko D, Baker S I, Li M, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Evidence for in vivo but not in vitro expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein F (OspF) homologue. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour A G. Linear DNA of Borrelia species and antigenic variation. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:236–239. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90139-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergstrom S, Bundoc V G, Barbour A G. Molecular analysis of linear plasmid-encoded major surface proteins, OspA and OspB, of the Lyme disease spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:479–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgdorfer W, Barbour A G, Hayes S F, Benach J L, Grunwaldt E, Davis J P. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science. 1982;216:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.7043737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll J A, Gherardini F C. Membrane protein variations associated with in vitro passage of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1996;64:392–398. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.392-398.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casjens S, van Vugt R, Tilly K, Rosa P A, Stevenson B. Homology throughout the multiple 32-kilobase circular plasmids present in Lyme disease spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:217–227. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.217-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champion C I, Blanco D R, Skare J T, Haake D A, Giladi M, Foley D, Miller J N, Lovett M A. A 9.0-kilobase-pair circular plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi encodes an exported protein: evidence for expression only during infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2653–2661. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2653-2661.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferdows M S, Barbour A G. Megabase-sized linear DNA in the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5969–5973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fikrig E, Barthold S W, Sun W, Feng W, Telford III S R, Flavell R A. Borrelia burgdorferi P35 and P37 proteins, expressed in vivo, elicit protective immunity. Immunity. 1997;6:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuchs R, Jauris S, Lottspeich F, Preac-Mursic V, Wilske B, Soutschek E. Molecular analysis and expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi gene encoding a 22 kDa protein (pC) in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:503–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Monco J C, Benach J L. Lyme neuroborreliosis. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:691–702. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilmore R D, Jr, Kappel K J, Dolan M C, Burkot T R, Johnson B J B. Outer surface protein C (OspC), but not P39, is a protective immunogen against a tick-transmitted Borrelia burgdorferi challenge: evidence for a conformational protective epitope in OspC. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2234–2239. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2234-2239.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilmore R D, Jr, Kappel K J, Johnson B J B. Molecular characterization of a 35-kilodalton protein of Borrelia burgdorferi, an antigen of diagnostic importance in early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:86–91. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.86-91.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guina T, Oliver D B. Cloning and analysis of a Borrelia burgdorferi membrane-interactive protein exhibiting haemolytic activity. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1201–1213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4291786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson R C, Marek N, Kodner C. Infection of Syrian hamsters with Lyme disease spirochetes. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:1099–1101. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.6.1099-1101.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson R C, Schmid G P, Hyde F W, Steigerwalt A G, Brenner D J. Borrelia burgdorferi sp. nov.: etiological agent of Lyme disease. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1984;34:496–497. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam T T, Nguyen T P, Montgomery R R, Kantor F S, Fikrig E, Flavell R A. Outer surface proteins E and F of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1994;62:290–298. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.290-298.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logigian E L, Kaplan R F, Steere A C. Chronic neurologic manifestations of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1438–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011223232102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marconi R T, Samuels D S, Garon C F. Transcriptional analyses and mapping of the ospC gene in Lyme disease spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:926–932. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.926-932.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery R R, Malawista S E, Feen K J, Bockenstedt L K. Direct demonstration of antigenic substitution of Borrelia burgdorferi ex vivo: exploration of the paradox of the early immune response to outer surface proteins A and C in Lyme disease. J Exp Med. 1996;183:261–269. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norris S J, Carter C J, Howell J K, Barbour A G. Low-passage-associated proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi B31: characterization and molecular cloning of OspD, a surface-exposed, plasmid-encoded lipoprotein. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4662–4672. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4662-4672.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norris S J, Howell J K, Garza S A, Ferdows M S, Barbour A G. High- and low-infectivity phenotypes of clonal populations of in vitro-cultured Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2206–2212. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2206-2212.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porcella S F, Popova T G, Akins D R, Li M, Radolf J D, Norgard M V. Borrelia burgdorferi supercoiled plasmids encode multicopy tandem open reading frames and a lipoprotein gene family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3293–3307. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3293-3307.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Probert, W. Personal communication.

- 24.Šadžiene A, Wilske B, Ferdows M S, Barbour A G. The cryptic ospC gene of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 is located on a circular plasmid. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2192–2195. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2192-2195.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saint Girons I, Old I G, Davidson B E. Molecular biology of the Borrelia, bacteria with linear replicons. Microbiology. 1994;140:1803–1816. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwan T G, Burgdorfer W. Antigenic changes of Borrelia burgdorferi as a result of in vitro cultivation. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:852–853. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.5.852-a. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwan T G, Burgdorfer W, Garon C F. Changes in infectivity and plasmid profile of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, as a result of in vitro cultivation. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1831–1836. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1831-1836.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwan T G, Piesman J, Golde W T, Dolan M C, Rosa P A. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2909–2913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simpson W J, Garon C F, Schwan T G. Analysis of supercoiled circular plasmids in infectious and non-infectious Borrelia burgdorferi. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinsky R J, Piesman J. Ear punch biopsy method for detection and isolation of Borrelia burgdorferi from rodents. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1723–1727. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.8.1723-1727.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steere A C. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:586–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908313210906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa P A. A family of genes located on four separate 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi B31. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3508–3516. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3508-3516.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suk K, Das S, Sun W, Jwang B, Barthold S W, Flavell R A, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi genes selectively expressed in the infected host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4269–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallich R, Brenner C, Kramer M D, Simon M M. Molecular cloning and immunological characterization of a novel linear-plasmid-encoded gene, pG, of Borrelia burgdorferi expressed only in vivo. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3327–3335. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3327-3335.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Y, Kodner C, Coleman L, Johnson R C. Correlation of plasmids with infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto type strain B31. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3870–3876. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3870-3876.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Hardham J M, Barbour A G, Norris S J. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]