Abstract

Most Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates are unable to use human hemoglobin as the sole source of iron for growth (Hgb−), but a minor population is able to do so (Hgb+). This minor population grows luxuriously on hemoglobin, expresses two outer membrane proteins of 42 kDa (HpuA) and 89 kDa (HpuB), and binds hemoglobin under iron-stressed conditions. In addition to the previously reported HpuB, we identified and characterized HpuA, which is encoded by the gene hpuA, located immediately upstream of hpuB. Expression of both proteins was found to be controlled at the translational level by frameshift mutations in a run of guanine residues within the hpuA sequence encoding the mature HpuA protein. The “on-phase” hemoglobin-utilizing variants contained 10 G’s, while the “off-phase” variants contained 9 G’s. Insertional hpuB mutants of FA19 Hgb+ and FA1090 Hgb+ no longer expressed HpuB but still produced HpuA. A polar insertional mutation of the upstream hpuA gene in FA1090 Hgb+ eliminated production of both HpuA and HpuB, whereas a nonpolar insertional mutant expressed HpuB only. Insertional mutagenesis of either hpuA or hpuB or both substantially decreased the hemoglobin binding ability of the FA1090 Hgb+ variant and prevented growth on hemoglobin plates. Therefore, both HpuA and HpuB were required for the utilization of hemoglobin for growth.

Mammalian hosts use iron-binding proteins and iron-sequestering compounds to maintain free iron at a level that is too low for the growth of invading bacterial pathogens (52). Several pathogenic organisms have developed specific mechanisms for iron acquisition which are induced under conditions of iron limitation. The genital mucosal pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae is known to use iron from lactoferrin and transferrin for growth (37, 38). The ability to use lactoferrin and transferrin is due to specific receptors (reviewed in reference 11). Gonococci also are able to utilize heme and certain heme-containing proteins as iron sources (15, 38). Two heme-binding proteins (99 and 44 kDa) have been isolated from the total membranes of gonococcal clinical isolates grown under iron-limited conditions (26, 29). Nevertheless, the mechanism of iron uptake from heme-containing proteins is unclear.

Mickelsen and Sparling (38) showed that 18 of 29 gonococcal strains studied were capable of using hemoglobin for growth. Lee and Hill (28) detected hemoglobin binding activity from Neisseria meningitidis grown under iron-limited conditions. More recently, two different meningococcal hemoglobin receptors have been described at the molecular level. Stojiljkovic et al. (49, 50) cloned a gene encoding an iron-regulated outer membrane protein, HmbR, which has amino acid similarity with the family of TonB-dependent membrane receptors. Lewis and Dyer (30) and Lewis et al. (31) described hpuAB, the hemoglobin-haptoglobin utilization operon of N. meningitidis, and suggested that HpuA and HpuB constitute a two-component receptor analogous to the bipartite transferrin receptor TbpB-TbpA (formerly named Tbp2-Tbp1) (reviewed in reference 11). Predicted amino acid sequences of N. meningitidis HpuA and HpuB indicate that, like TbpB and TbpA, HpuB belongs to the TonB-dependent family of high-affinity transport proteins and HpuA is probably a lipoprotein (31).

We previously reported that all tested gonococcal strains can use hemoglobin as a sole source of iron for growth by switching from a non-hemoglobin-utilizing phenotype (Hgb−) to a hemoglobin-utilizing phenotype (Hgb+) in vitro. In order to distinguish these two phenotypes of the same strain, we classified gonococci able to grow on hemoglobin-Desferal plates as Hgb+ variants and those unable to grow on hemoglobin-Desferal plates as Hgb− variants (8). The ability to use hemoglobin for growth appears to be a phase-varying phenomenon, because Hgb+ variants arise from Hgb− parents at a frequency of about 1 × 10−4 to 2 × 10−3 (8). In this communication, we describe the mechanism underlying the phase variation of hemoglobin utilization and the characteristics of a 42-kDa HpuA protein encoded by the gonococcal hpuA gene. We also previously reported that insertional mutants that no longer expressed the 89-kDa HpuB protein cannot utilize hemoglobin to support growth but still grow on heme (8). Now we report on the requirement for HpuA in the utilization of hemoglobin for growth by N. gonorrhoeae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

N. gonorrhoeae strains used are listed in Table 1. Both Hgb+ and Hgb− variants of FA1090 and FA19 were used. Growth conditions were the same as those described by Chen et al. (8), with the exception that the iron chelator Desferal (deferoxamine mesylate; CIBA Pharmaceutical Co.) was used at a 100 μM final concentration for FA1090 and insertional mutants of FA1090. The abilities of FA1090 Hgb− and Hgb+ variants and their hpuA and/or hpuB insertional mutants to grow on heme were tested on modified gonococcal medium base (GCB) agar plates (8) containing bovine hemin chloride (Sigma) at 5 mg/liter and Desferal at 100 μM. Antibiotic selection in gonococci employed erythromycin at 1 mg/liter for mini-Tn3erm insertions (30), spectinomycin at 100 mg/liter for the Ω interposon insertions (44), and kanamycin at 60 mg/liter for the aphA-3 cassette insertions (35).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Gonococcal strains | ||

| FA1090 | Wild type; Hgb+ and Hgb− variants | 41 |

| FA19 | Wild type; Hgb+ and Hgb− variants | 38 |

| FA6929 | FA1090 Hgb+; hpuB::mTn3erm | 8 |

| FA6930 | FA19 Hgb+; hpuB::mTn3erm | 8 |

| FA6981 | FA1090 Hgb−; hpuA::Ω | This work |

| FA6982 | FA1090 Hgb+; hpuA::Ω | This work |

| FA6983 | FA1090 Hgb+; hpuA::aphA-3 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSM85k | 850-bp ApoI fragment of hpu in pHS8 | 30 |

| pSM85kE | pSM85k::mTn3erm; source for hpuB::mTn3erm | 30 |

| pHP45Ω | Source for Ω interposon (Smr) | 44 |

| pUC18K | 850-bp aphA-3 cassette in pUC18 (Kmr) | 35 |

| pUNCH258 | hpuA clone from FA1090 Hgb− in pCRII | This work |

| pUNCH259 | hpuA clone from FA1090 Hgb+ in pCRII | This work |

| pUNCH260 | NarI-XbaI segment from pUNCH 258; hpuA fragment with no poly(G) tract | This work |

| pUNCH268 | PpuMI-cut pUNCH260 with SmaI-cut Ω in pBluescript II KS+ | This work |

| pUNCH271 | PpuMI-cut pUNCH260 with SmaI cut-aphA-3 in pBluescript II KS+ | This work |

Sequencing the gonococcal hpuA gene.

Double-stranded PCR products, purified with a Geneclean II kit (Bio 101, Inc.), were sequenced directly. Chromosomal DNAs of FA1090 Hgb+ and FA1090 Hgb− were used as templates for PCRs. Initially, the putative open reading frame of FA1090 hpuA was identified from the database of the Gonococcal Genome Sequencing Project (Advanced Center for Genome Technology, University of Oklahoma) by searching for the coding sequence of the N terminus of FA1090 HpuB (8). The 19-mer upstream PCR primer (hpu.01, GCAGGCACGTCCGATTTCC) was designed based on the sequence 108 bp upstream of the ATG codon of the putative hpuA open reading frame (Fig. 1). A 20-mer downstream primer (hpu.14, ACAAAACCCAAAAACTCGGAC) was designed, based on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of HpuB, to generate PCR DNA fragments covering the entire hpuA gene (Fig. 1). Two PCRs were carried out for each variant. One used purified chromosomal DNA, and the other used boiled cells, as the template. PCR products were pooled for sequencing. Both strands of the PCR-generated hpuA DNA were sequenced by using hpu.01, hpu.14, and four additional internal primers.

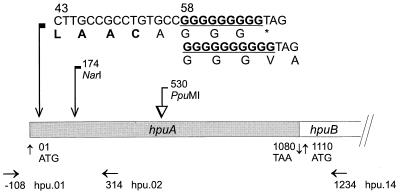

FIG. 1.

Descriptive map of FA1090 hpuA. Numbers indicate positions of first nucleotides. The open reading frames (ORFs) for hpuA and hpuB start at nucleotide positions 01 and 1,110, respectively. Beginning from position 43 is a consensus coding sequence for a type-II signal peptidase cleavage site, LAAC. A run of multiple guanine residues was located in hpuA, starting from position 58. The asterisk indicates a stop codon. A 1,130-bp fragment was isolated between the NarI site in hpuA and an XbaI site in the vector for mutagenesis. The PpuMI site was the insertion site for making various mutants. The primer pair, hpu.01 and hpu.14, was used in PCRs for the cloning of hpuA. The other primer pair, hpu.01 and hpu.02, was used to generate PCR products for enumerating guanine residues in the poly(G) tract.

In order to verify that hemoglobin-utilizing and non-hemoglobin-utilizing variants of N. gonorrhoeae contained different numbers of guanine (G) residues in the poly(G) tract of hpuA, guanine residues were enumerated from sequences of PCR products covering the poly(G) tract but not the entire hpuA. Two sets of templates were prepared from each variant of FA19 and FA1090. One was the purified chromosomal DNA, and the other was boiled cells. A 19-mer downstream primer (hpu.02, CATCTTCAAAACACCCGGC) was designed based on the sequence 247 bp downstream from the end of the poly(G) tract (314 bp from the initial ATG codon shown in Fig. 1). PCRs using the primer pair hpu.01 and hpu.02 were expected to generate DNA fragments of 439 bp from Hgb− variants and of 440 bp from Hgb+ variants. Sequencing of PCR-generated partial FA1090 hpuA fragments was carried out on both strands with primers hpu.01 and hpu.02. Sequencing of PCR-generated partial FA19 hpuA fragments was carried out on single strands only.

Oligonucleotides were synthesized at the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center DNA Synthesis Facility of the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill. DNA sequencing was carried out at the Automated DNA Sequencing Facility of the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill with an Applied Biosystems model 373 DNA sequencer by use of the Tag DyeDeoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems).

Cloning of the hpuA gene.

Routine molecular cloning techniques as described by Sambrook et al. (47) were used. Plasmid DNAs were isolated by either the Wizard Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega) or the Qiagen DNA purification system. Chromosomal DNA from N. gonorrhoeae was purified by the method of Stern et al. (48). The 1,360-bp PCR DNA made from the FA1090 Hgb− template and the 1,361-bp PCR DNA made from the FA1090 Hgb+ template were inserted into the pCRII vector by using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) to yield pUNCH258 and pUNCH259, respectively.

Insertional mutagenesis of the hpuA gene. (i) Construction of polar hpuA insertional mutants.

In order to avoid potential variations in the poly(G) region during experimental manipulation of hpuA, insertional mutagenesis of hpuA was carried out within a NarI-XbaI fragment isolated from pUNCH258 (Fig. 1). The NarI site was located 108 bp downstream of the poly(G) tract, and the XbaI site was present in the polylinker of pCRII. The NarI-XbaI fragment was subcloned into the pBluescript II KS+ phagemid (Stratagene) digested with XbaI-AccI to yield pUNCH260. In order to avoid blocking of PpuMI digestion by Dcm methylase activity, pUNCH260 was moved from Escherichia coli DH5αMCR (Bethesda Research Laboratories) to GM2163 (New England Biolabs). The 2-kb Ω interposon fragment isolated from SmaI-cut pHP45Ω (44) was ligated with pUNCH260, digested with PpuMI, and filled in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (Fig. 1) to yield pUNCH268. pUNCH268, containing an Ω insert in the hpuA fragment, was then transformed into FA1090 Hgb− and FA1090 Hgb+ to generate FA6981 and FA6982, respectively. Transformant colonies were screened for resistance to spectinomycin at 100 mg/liter and the inability to grow on hemoglobin-Desferal plates.

(ii) Construction of a nonpolar hpuA insertional mutant.

A mutagenic cassette designed to be inserted into a gene of an operon without affecting transcription of downstream genes (35) was adopted for our construction of a nonpolar hpuA mutant. The 800-bp aphA-3 insert cassette was isolated from pUC18K by SmaI digestion (35) and was ligated to PpuMI-digested pUNCH260 to generate pUNCH271. pUNCH271 was then transformed into FA1090 Hgb+ to create FA6983. Transformant colonies were screened for resistance to kanamycin at 60 mg/liter and the inability to grow on hemoglobin-Desferal plates.

Enumeration of G residues.

The cloned hpuA gene in pUNCH258 and pUNCH259 was sequenced with M13 reverse primer (Invitrogen). The guanine residues in hpuA from FA6981, FA6982, and FA6983 were enumerated from PCR products generated by the primer pair hpu.01 and hpu.02 in order to confirm that gonococcal transformants containing the mutagenized fragment of hpuA kept the same number of guanine residues in the poly(G) tract as was present in the parents. Primer hpu.01 was used in sequencing those partial hpuA fragments from mutants.

DNA hybridization.

Southern blots were utilized to confirm that allelic exchange occurred as expected. Chromosomal DNAs of FA1090 Hgb−, FA1090 Hgb+, and hpuA or hpuB insertional mutants of FA1090 Hgb+ (FA6982, FA6983, and FA6929) were digested with ClaI and separated on 0.7% agarose gels. Gels were transferred bidirectionally to Magnagraph nylon membranes (Micron Separations). Blots were probed, as described in Results, with random-primed digoxigenin-dUTP-labeled DNA and were developed according to the Genius labeling and detection instructions (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals).

Peptide synthesis and immunization.

A 20-mer peptide was designed based on the predicted strong antigenicity of the last 17 amino acids of the C terminus of HpuA (CGG-EKKLDDTSQDTNHLTKQ). Another peptide (CGG-ADPAPQSAQTLN) was designed previously based on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of HpuB (8). Peptide synthesis was performed at the University of North Carolina Program in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology MicroProtein Chemistry Facility with a multiple peptide synthesizer (Rainin Symphony). Peptide synthesis and immunization followed the procedures described by Elkins (16) and Chen et al. (8).

Affinity purification of antibodies raised against the N-terminal peptide of HpuB and the C-terminal peptide of HpuA.

Postimmune antipeptide sera for HpuB (8) and HpuA were each affinity purified to eliminate reactivity to antigens other than HpuA and HpuB. A modification of a previously published method as reported by Elkins et al. (17) was used for the affinity purification of antipeptide antibodies on immobilized peptide coupled on thiopropyl-agarose columns (Sigma) (42).

Preparations of whole-cell dot blots and outer membranes from gonococci grown under iron-replete and iron-stressed conditions.

Gonococci were grown in iron-sufficient and iron-limited media. Gonococcal medium broth containing Kellogg’s supplement I was inoculated from overnight plate-grown gonococcal cultures (Hgb− on GCB plates and Hgb+ on hemoglobin-Desferal plates). After one mass doubling, cultures were split. Desferal was added to a 100 μM concentration to induce iron starvation in one flask, whereas supplement II (ferric nitrate at 12 μM) was added to the other flask. After 4 h of growth with either the chelator or the iron supplement, cells were harvested by centrifugation. The density of harvested cells was adjusted to an optical density of 0.2 at 600 nm (approximately 2 × 108 CFU/ml) with phosphate-buffered saline. Dot blots were prepared from wells loaded with 100 μl of the adjusted cell suspensions. Total membranes and outer membranes were prepared as previously described (16). The protein content was determined by a bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce).

Purification of hemoglobin-binding proteins from total membranes.

Purification of hemoglobin-binding proteins used bovine hemoglobin-agarose (chromatography specialty resin) supplied by Sigma. Purification with solid-phase hemoglobin-agarose followed a procedure described by Elkins (16). Hemoglobin-binding proteins were eluted in Laemmli sample buffer for analytical sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting (immunoblotting).

Whole-cell dot blot hemoglobin binding assay.

FA1090 Hgb+, FA6929, and hpuA insertional mutants of FA1090 Hgb+ (FA6982 and FA6983) were examined for their ability to bind hemoglobin in a whole-cell dot blot assay. Human hemoglobin was biotinylated with N-hydroxysuccinimide–SS–Biotin (21331D; Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions at a molar ratio of 23:1 at 4°C for 2 h. The unbound biotin was removed by dialysis overnight in phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C. The binding was detected by a colorimetric procedure using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Pierce) as the secondary reagent.

Western blot analysis of membrane proteins.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting of total membrane proteins, outer membrane proteins, and hemoglobin-binding proteins purified from total membranes were performed as described by Harlow and Lane (20). One nitrocellulose membrane each was prepared for Western blotting of total membrane, outer membrane, and hemoglobin-binding proteins. These membranes were cut into upper and lower panels along a line drawn between 55 and 60 kDa. The upper panels were probed with affinity-purified serum raised against the N-terminal peptide of HpuB (8), and the lower panels were probed with affinity-purified serum raised against the C-terminal peptide of HpuA.

RESULTS

Gonococcal hpuA gene.

We obtained the sequence of hpuA from both FA1090 Hgb− and FA1090 Hgb+ by sequencing PCR products of the primer pair hpu.01 and hpu.14 directly. Data containing DNA sequence of FA1090 hpuA have been released incrementally by the N. gonorrhoeae Genome Sequencing Project. The sequence identical to our FA1090 Hgb− hpuA sequence was released as part of the February 1997 update. Since the sequence of the FA1090 hpuAB operon is now readily available from the database of the project (the University of Okalahoma’s Advanced Center for Genome Technology at http://www.dna1.chem.uoknor.edu) and from GenBank (accession no. AF031495), the hpuA sequence is not listed in detail in this communication.

FA1090 hpuA was located immediately upstream from hpuB, and there was no obvious promoter sequence in the 27 nucleotides that separate hpuA and hpuB. In the hemoglobin-utilizing variant, the hpuA gene had an open reading frame of 1,079 bp, 56 bp longer than that in the hemoglobin-haptoglobin-utilizing N. meningitidis strain DNM2 (31) (GenBank accession no. U73112). The putative Fur box in the promoter region of FA1090 hpuA was identical to that reported for DNM2. Forty-three base pairs downstream from the ATG codon was the beginning of a consensus sequence for a type-II signal peptidase cleavage site, LAAC (21) (Fig. 1). Processing of the gonococcal HpuA at the LAAC site would produce a mature peptide of 343 amino acids at a molecular size of 36 kDa. The isoelectric point of unmodified mature peptide was predicted to be 6.77. The putative HpuA of FA1090 Hgb+ had an unusual amino acid composition, containing 12.2% serine and 11.9% glycine. There was 84.2% similarity and 82.0% identity to the HpuA of DNM2.

One codon after the coding sequence for LAAC was a run of G residues, starting at nucleotide 58 of hpuA (Fig. 1). Direct sequencing of hpuA PCR products revealed that the FA1090 variant unable to utilize hemoglobin for growth contained only 9 G’s in the poly(G) tract, while the hemoglobin-utilizing variant of FA1090 contained 10 G’s. Identical results were obtained from each of the four independent PCRs for both the Hgb− variant and the Hgb+ variant. PCR products from FA19 Hgb− and FA19 Hgb+, two reactions each, also contained 9 G’s for the nonhemoglobin-utilizing variant and 10 G’s for the hemoglobin-utilizing variant. Since the number of G’s in both strains was consistent for the respective variants, the difference in numbers was variant specific and not the result of PCR error. Deletion of 1 G from the 10-G poly(G) tract resulted in a frame shift in the coding sequence for HpuA and led to an immediate stop codon (Fig. 1). Thus, changes in the expression states of hpuA involved an altered reading frame register and resulted in switches between the “on phase” and the “off phase” of hemoglobin utilization.

PCR clones and insertional mutants of hpuA.

Curiously, pUNCH258 and pUNCH259, which were plasmids containing cloned hpuA from FA1090 Hgb− and FA1090 Hgb+, respectively, both contained 9 G’s in the poly(G) tract. It seems that reversion had occurred in the E. coli transformation of pUNCH259 and that the selection was skewed to clones containing 9 G’s. Insertional mutagenesis of FA1090 Hgb+ resulted in hpuB mutant FA6929 (8) and hpuA mutants FA6982 and FA6983. All three mutants contained 10 G’s in the poly(G) tract, whereas the hpuA insertional mutant of FA1090 Hgb−, FA6981, contained 9 G’s. Thus, gonococcal transformation with a fragment of hpuA containing either the Ω interposon or the aphA-3 cassette did not alter the poly(G) region. Changes in hemoglobin utilization phenotypes of these transformants reflected changes that resulted from insertional inactivation of the hpuA and/or the hpuB alleles.

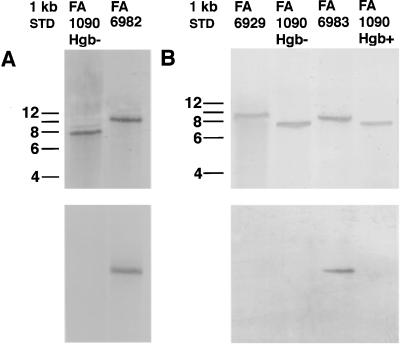

Southern blot analysis of hpuA insertional mutants.

In order to confirm that each mutant had the appropriate insertion, Southern blotting was performed with three separate DNA probes. One was an 850-bp hpuB fragment of the EcoRI digest of the plasmid pSM85k (30). The other two were the DNA fragments of SmaI-cut Ω interposon (2,082 bp) and SmaI-cut aphA-3 cassette (787 bp). When chromosomal DNA from either FA1090 Hgb− or FA1090 Hgb+ was digested with ClaI, the hpuB probe hybridized with a DNA fragment of roughly 8 kb. In FA6929, FA6982, or FA6983, the same probe hybridized with fragments of approximately 9 to 10 kb. Due to the large sizes of ClaI-digested fragments, exact sizes of labeled fragments were hard to estimate; nevertheless, sizes of fragments from the mutants were appropriately larger than the size of the fragment from the parent (Fig. 2, upper panel). The Ω probe hybridized with FA6982 DNA only (Fig. 2A, lower panel), and the aphA-3 probe hybridized with FA6983 DNA only (Fig. 2B, lower panel), at the appropriate size positions as predicted.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of hpuA and hpuB insertional mutants. Chromosomal DNAs from FA1090 parent and mutant strains were digested with ClaI and transferred bidirectionally to prepare two blots per gel. Hgb− was the non-hemoglobin-utilizing variant, while Hgb+ was the hemoglobin-utilizing variant and the recipient for insertional mutation. (A) Blots of DNA fragments from FA6982, a polar insertional hpuA mutant, were probed with an hpuB fragment (upper panel) and an Ω fragment (lower panel). (B) Blots of DNA fragments from FA6929, an hpuB mutant, and FA6983, a nonpolar hpuA mutant, were probed with an hpuB fragment (upper panel) and an aphA-3 fragment (lower panel).

Localization of the HpuA protein.

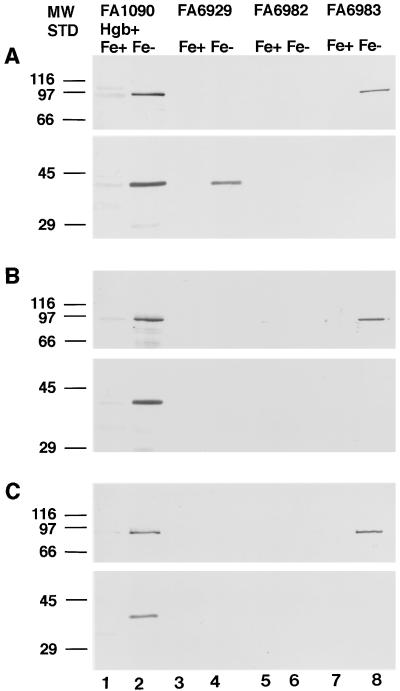

Expression of both HpuA and HpuB was iron regulated. While HpuB could be detected in stained gels of whole-cell lysates, total membrane proteins, outer membrane proteins, or hemoglobin-binding proteins (8), HpuA was not readily visible in the Coomassie-stained gels, the silver-stained (51) gels, or autoradiographs of iodinated membrane protein gels (data not shown). However, Western blotting with affinity-purified antibody raised against the C-terminal peptide of HpuA revealed an iron stress-induced 42-kDa band in whole cells (data not shown) and membrane preparations. This band appeared along with the 89-kDa HpuB in iron-stressed FA1090 Hgb+ (Fig. 3A and B, lanes 2) and FA19 Hgb+ (data not shown) but was absent in the hpuA insertional mutants FA6982 and FA6983 (Fig. 3A and B, lanes 6 and 8). The HpuA of hemoglobin-utilizing variants could be affinity purified from total membrane proteins with immobilized hemoglobin (Fig. 3C, lane 2).

FIG. 3.

Detection of HpuA and HpuB among the total membrane proteins (A), the outer membrane proteins (B), and the hemoglobin-binding proteins (C) prepared from the hpuA and/or hpuB mutants of FA1090 Hgb+ grown under iron-replete (Fe+) or iron-stressed (Fe−) conditions. FA6929 is an hpuB insertional mutant, and FA6982 and FA6983 are polar and nonpolar hpuA insertional mutants, respectively. Western blots of total membrane proteins, outer membrane proteins, and hemoglobin-binding affinity-purified proteins were cut into two panels each, one probed with affinity-purified anti-HpuB serum (upper panels) and the other probed with affinity-purified anti-HpuA serum (lower panels).

Expression of HpuA and HpuB in mutants.

Since we were unable to identify any consensus promoter sequence for hpuB, it was expected that insertional mutation of the upstream hpuA with the Ω interposon would prevent expression of both HpuA and HpuB. On the other hand, since the aphA-3 gene is preceded by translation stop codons in all three reading frames and is followed by a consensus ribosome binding site and a start codon (35), it was expected that successful insertion of the aphA-3 cassette in hpuA would prevent expression of HpuA but not of HpuB.

HpuA was present in the total membrane proteins prepared from the iron-stressed hpuB mutant FA6929 (Fig. 3A, lane 4). However, when HpuB was absent, HpuA could no longer be detected in either the outer membrane protein blot or the hemoglobin-binding protein blot (Fig. 3B and C, lanes 4). The polar insertional hpuA mutant, FA6982, showed neither HpuA nor HpuB in all three blots (Fig. 3, lanes 6). The nonpolar insertional hpuA mutant, FA6983, did not produce HpuA but did produce HpuB, as expected (Fig. 3A and B, lanes 8). The amount of HpuB produced in the nonpolar hpuA mutant might have been reduced, compared to that produced by parent strain, but precise quantification of expression levels was not attempted. The hemoglobin binding ability of HpuB from FA6983 apparently was not affected by the absence of HpuA (Fig. 3C, lane 8).

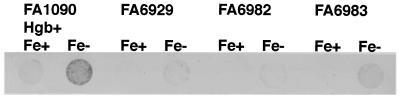

Hemoglobin binding and utilization of hpuA insertional mutants.

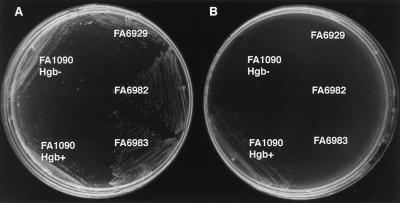

Iron-stressed, hemoglobin-utilizing FA1090 Hgb+ bound biotinylated human hemoglobin in a whole-cell dot blot assay (Fig. 4). The binding was inhibited by excess unlabeled hemoglobin but not by excess hemin at a molar ratio of 100:1 (data not shown). The hpuB insertional mutant, FA6929, and the polar and nonpolar hpuA insertional mutants, FA6982 and FA6983, all demonstrated impaired binding of biotinylated hemoglobin (Fig. 4). None of the hpuA or hpuB mutants of FA1090 Hgb+ (FA6929 [HpuA+ HpuB−], FA6982 [HpuA− HpuB−], or FA6983 [HpuA− HpuB+]) was able to grow on modified GCB plates using human hemoglobin as the sole iron source (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, all three mutants and both FA1090 Hgb− and FA1090 Hgb+ grew well on modified GCB plates containing hemin (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Dot blot assay showing binding of biotinylated human hemoglobin to iron-replete (Fe+) and iron-stressed (Fe−) whole cells. FA1090 Hgb+ is the parent strain. FA6929 is an hpuB insertional mutant, and FA6982 and FA6983 are polar and nonpolar hpuA insertional mutants, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Growth phenotypes on GCB plate (A) and hemoglobin-Desferal plate (B). FA1090 Hgb− is the non-hemoglobin-utilizing variant, and FA1090 Hgb+ is the hemoglobin-utilizing variant. FA6929 is an hpuB insertional mutant, and FA6982 and FA6983 are polar and nonpolar hpuA insertional mutants of FA1090 Hgb+, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In order to examine the mechanism underlying the phase variation of hemoglobin utilization by N. gonorrhoeae, we studied the expression and function of a 42-kDa outer membrane protein, HpuA, identified in the hemoglobin-utilizing variants of both FA19 and FA1090 grown under iron-stressed conditions. While hpuA was located immediately upstream from hpuB, the gene encoding the previously reported 89-kDa hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein (8), we were unable to identify any consensus promoter sequence that might direct the transcription of hpuB within the short DNA fragment between the stop codon of hpuA and the start codon of hpuB. Polar insertional mutation of hpuA prevented production of both HpuA and HpuB. Thus, it is most likely that, in N. gonorrhoeae, hpuA and hpuB are comprised in a two-component operon similar to that in N. meningitidis (31).

Variation in the expression of gonococcal HpuA and HpuB was associated with variation in the length of a run of G residues at the 5′ end of hpuA, located within the sequence encoding the N-terminal amino acids for mature protein. The hemoglobin-utilizing variants contained 10 G’s, whereas the non-hemoglobin-utilizing variants contained 9 G’s (Fig. 1). When hpuA had only 9 G’s, a stop codon occurred immediately at the end of the poly(G) tract. In Hgb+ variants, the 10-G poly(G) tract enabled a change of the translational reading frame and thus the expression of HpuA and HpuB. This apparently explains the high frequency (1 × 10−4 to 2 × 10−3) of spontaneous Hgb−-to-Hgb+ variation observed in all tested gonococcal strains (8). Other gonococcal phase-varying systems include Pil (19, 36), PilC (25), Opa (33, 48), and lipooligosaccharide (2). The mechanism for phase variation of HpuA and HpuB is similar to that for Opa, PilC, and lipooligosaccharide in that each apparently uses slipped-strand mispairing to alter the length of a short DNA repeat, which affects translational frame and therefore expression (13, 18, 25, 39, 40).

Although we have been unable to develop a protocol to detect the on-phase-to-off-phase switch of hemoglobin utilization, it is likely that the postulated on-to-off switch also occurs at a relatively high frequency. It is unclear what advantage might be gained by phase variation and iron repression of hemoglobin-binding protein expression. We speculate, however, that phase variation of a hemoglobin-binding protein in gonococci would enable efficient utilization of menstrual hemoglobin. Recently, two genes encoding hemoglobin-binding proteins of Haemophilus influenzae (HgpA and HgpB) have been cloned (23, 24, 45). Regions of CCAA nucleotide-repeating units immediately following the putative leader cleavage site were identified in both hgpA and hgpB. It has been postulated that alteration of the reading frame across the CCAA region of hgpA or hgpB by strand slippage would lead to production of either protein (23). Thus, the heme-regulated expression of H. influenzae hemoglobin-binding proteins might very well be another example of phase variation of hemoglobin-binding proteins.

The gonococcal hpuA gene encodes a consensus signal peptidase II cleavage site (21), suggesting that HpuA is lipid modified. The difference between the observed molecular mass (42 kDa) and the calculated molecular mass (36 kDa) is consistent with lipid modification of HpuA. The nonintegral membrane protein characteristics of HpuA were demonstrated in membrane preparations of the HpuA+ HpuB− mutant FA6929. In the absence of the integral outer membrane protein HpuB, HpuA could not be detected among Sarkosyl-resistant outer membrane proteins (Fig. 3B) or total membrane proteins subjected to hemoglobin-agarose purification (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, the absence of HpuA had no obvious effect on the hemoglobin binding ability of HpuB (Fig. 3C). It is possible that the apparently decreased binding of FA6983 cells to biotinylated hemoglobin (Fig. 4) was due to decreased production of HpuB instead of impaired hemoglobin binding by HpuB (Fig. 3C).

We could not detect hemoglobin binding by HpuA alone in cell-free systems, but HpuA must play a critical role in the utilization of hemoglobin for growth. FA6983, the mutant which expressed HpuB but not HpuA, bound hemoglobin in affinity purification (Fig. 3C) but was unable to grow on media where hemoglobin was the sole source of iron (Fig. 5). Thus, HpuA and HpuB, while showing differences in their abilities to bind hemoglobin, were both required for hemoglobin utilization by gonococci.

Lee (26) reported isolation of two hemin-binding proteins (HmBPs) by affinity purification from gonococci grown under iron-limited conditions. These two HmBPs have observed molecular masses of 44 and 97 kDa, very close to the 42 and 89 kDa of HpuA and HpuB. HmBPs bound to hemin-agarose, and the binding was competitively inhibited by hemoglobin. Growth on hemoglobin was inhibited by a monoclonal antibody directed against the 97-kDa HmBP (26, 29). These results suggest that HmBPs might be identical to HpuA and HpuB. However, our results showed that neither HpuA nor HpuB was required for growth on hemin plates, and in whole-cell dot blot assays, hemoglobin binding by FA1090 Hgb+ was not affected by excess hemin. These are not the results that would be expected if HpuA and HpuB were identical to the HmBPs. In the current absence of sequence data for the HmBPs, and of specific mutants of the HmBPs, we cannot be certain that HpuA and HpuB are different from the HmBPs.

Gonococci possess multiple specific systems to acquire iron from different sources: transferrin and lactoferrin (4, 5, 11, 34), aerobactin (54), enterobactin (46), hemoglobin (38), and, undoubtedly, heme (14, 15, 27). This presumably reflects the differences in available iron at different body sites and under different physiological conditions (53). Acquisition of iron from transferrin, lactoferrin, and hemoglobin may involve a bipartite receptor system. The operon, tbpBA, encoding the outer membrane lipoprotein, TbpB, and the TonB-dependent outer membrane transferrin receptor, TbpA, has been well studied (1, 10, 11). It is also known that there is a gene for a lipoprotein homologous to tbpB in meningococci immediately upstream of lbpA, which encodes the TonB-dependent lactoferrin receptor LbpA (6, 7, 32, 43). Recently, a similar lipoprotein gene has been found in N. gonorrhoeae, immediately upstream of lbpA (3).

The HpuA-HpuB receptor system for utilization of hemoglobin in N. gonorrhoeae is similar in several respects to that of TbpB-TbpA. Gonococcal TbpB, a lipid-modified protein, binds to transferrin in affinity purification but cannot be affinity purified from a TbpA− mutant in the presence of the detergent Sarkosyl (9). HpuA, the lipoprotein analogous to TbpB, was not Sarkosyl resistant and could be affinity purified only in the presence of HpuB, the integral outer membrane protein analogous to TbpA. This could reflect a physical association between HpuA and HpuB, such as has been proposed for TbpB and TbpA (12). In N. gonorrhoeae, a TbpB− mutant shows reduced binding of transferrin but exhibits growth on transferrin plates; a TbpA− mutant binds less transferrin and does not grow on transferrin plates (1). In these respects, the gonococcal TbpB-TbpA system does not correspond to what we have described for HpuA and HpuB; however, in N. meningitidis, both TbpB− and TbpA− mutants are unable to grow on transferrin-bound iron (22), analogous to the results for the gonococcal HpuA-HpuB system.

The importance of both HpuA and HpuB in gonococcal hemoglobin utilization has been demonstrated, but many questions remain to be answered concerning the exact function and location of HpuA and HpuB. A better understanding of how they interact to facilitate iron uptake from hemoglobin will be the aim of future work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to William Shafer of Emory University for providing us with plasmid pUC18k. We thank members of the Sparling laboratory and Cynthia Cornelissen of Virginia Commonwealth University for helpful discussions and for critiquing the manuscript, Christopher Thomas for assistance in analyzing cloning and sequencing data, and Annice Rountree for her expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI31496 and AI26837 to P. Frederick Sparling. Ching-ju Chen was supported by institutional STD training grant AI07001.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson J E, Sparling P F, Cornelissen C N. Gonococcal transferrin-binding protein 2 facilitates but is not essential for transferrin utilization. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3162–3170. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3162-3170.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apicella M A, Shero M, Jarvis G A, Griffiss J M, Mandrell R E, Schneider H. Phenotypic variation in epitope expression of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae lipooligosaccharide. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1755–1761. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1755-1761.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas, G., and P. F. Sparling. 1997. Personal communication.

- 4.Biswas G D, Sparling P F. Characterization of lbpA, the structural gene for a lactoferrin receptor in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2958–2967. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2958-2967.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanton K J, Biswas G D, Tsai J, Adams J, Dyer D W, Davis S M, Koch G G, Sen P K, Sparling P F. Genetic evidence that Neisseria gonorrhoeae produces specific receptors for transferrin and lactoferrin. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5225–5235. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5225-5235.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnah R A, Wong H, Schryvers A B. Genetic and serological analysis of lactoferrin receptors in the Neisseria: evidence for the antigenically conserved nature of LbpB, abstr. 1996. p. 206. p. 560. In W. Zollinger, C. Frasch, and C. Deal (ed.), Abstracts of the Tenth International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnah R A, Yu R-H, Schryvers A B. Biochemical analysis of lactoferrin receptors in the Neisseriaceae: identification of a second bacterial lactoferrin receptor. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:285–297. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(96)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C-J, Sparling P F, Lewis L A, Dyer D W, Elkins C. Identification and purification of a hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein from Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5008–5014. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5008-5014.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornelissen C, Sparling P F. Binding and surface exposure characteristics of the gonococcal transferrin receptor are dependent on both transferrin-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1437–1444. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1437-1444.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelissen C N, Biswas G D, Tsai J, Paruchuri D K, Thompson S A, Sparling P F. Gonococcal transferrin-binding protein 1 is required for transferrin utilization and is homologous to TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5788–5797. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5788-5797.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornelissen C N, Sparling P F. Iron piracy: acquisition of transferrin-bound iron by bacterial pathogens. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:843–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornelissen C N, Anderson J E, Sparling P F. Energy-dependent changes in the gonococcal transferrin receptor. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:25–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5381914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danaher R J, Levin J C, Arking D, Burch C L, Sandlin R. Genetic basis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lipooligosaccharide antigenic variation. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7275–7279. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7275-7279.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai P J, Nzeribe R, Genco C A. Binding and accumulation of hemin in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4634–4641. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4634-4641.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyer D W, West E P, Sparling P F. Effects of serum carrier proteins on the growth of pathogenic Neisseriae with heme-bound iron. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2171–2175. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2171-2175.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elkins C. Identification and purification of a conserved heme-regulated hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1241–1245. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1241-1245.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elkins C, Carbonetti N H, Varela V A, Stirewalt D, Klapper D G, Sparling P F. Antibodies to N-terminal peptides of gonococcal porin are bactericidal when gonococcal lipopolysaccharide is not sialylated. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2617–2628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gotschlich E C. Genetic locus for the biosynthesis of the variable portion of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lipooligosaccharide. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2181–2190. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagblom P, Segal E, Billyard E, So M. Intragenic recombination leads to pilus antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nature. 1985;315:156–158. doi: 10.1038/315156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi S, Wu H C. Lipoprotein in Bacteria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1990;22:451–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00763177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irwin S W, Averil C Y, Cheng C Y, Schryvers A B. Preparation and analysis of isogenic mutants in the transferrin receptor protein genes, tbpA and tbpB, from Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1125–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin H, Ren Z, Pozsgay J M, Elkins C, Whitby P W, Morton D J, Stull T L. Cloning of a DNA fragment encoding a heme-repressible hemoglobin-binding protein outer membrane protein from Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3134–3141. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3134-3141.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin H, Ren Z, Whitby P W, Morton D J, Stull T L. Abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Genetic analysis of a hemoglobin binding protein (HgpA) of Haemophilus influenzae, abstr. B-223; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonsson A B, Nyberg G, Normark S. Phase variation of gonococcal pili by frameshift mutation in pilC, a novel gene for pilus assembly. EMBO J. 1991;10:477–488. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee B C. Isolation of haemin-binding proteins of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Med Microbiol. 1992;36:121–127. doi: 10.1099/00222615-36-2-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee B C. Quelling the red menace: haem capture by bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:383–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee B C, Hill P. Identification of an outer-membrane haemoglobin-binding protein in Neisseria meningitidis. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2647–2656. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-12-2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee B C, Levesque S. A monoclonal antibody directed against the 97-kilodalton gonococcal hemin-binding protein inhibits hemin utilization by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2970–2974. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2970-2974.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis L A, Dyer D W. Identification of an iron-regulated outer membrane protein of Neisseria gonorrhoeae involved in the utilization of hemoglobin complexed to haptoglobin. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1299–1306. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1299-1306.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis L A, Gray E, Wang Y-P, Roe B A, Dyer D W. Molecular characterization of hpuAB, the haemoglobin-haptoglobin-utilization operon of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:737–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2501619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis L A, Rohde K H, Behrens B, Gray E, Toth S I, Roe B A, Dyer D W. Molecular analysis of lbpAB encoding the two-component meningococcal lactoferrin receptor, abstr. P-214. In: Zollinger W, Frasch C, Deal C, editors. Abstracts of the Tenth International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference. 1996. p. 557. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayer L W. Rates of in vitro changes in gonococcal colony opacity phenotypes. Infect Immun. 1982;37:481–485. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.481-485.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKenna W R, Mickelsen P A, Sparling P F, Dyer D W. Iron uptake from lactoferrin and transferrin by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1988;56:785–791. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.4.785-791.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ménard R, Sansonetti P J, Parsot C. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5899–5906. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5899-5906.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer T F, Mlawer N, So M. Pilus expression in Neisseria gonorrhoeae involves chromosomal rearrangement. Cell. 1982;30:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mickelsen P A, Blackman E, Sparling P F. Ability of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and commensal Neisseria species to obtain iron from lactoferrin. Infect Immun. 1982;35:915–920. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.915-920.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mickelsen P A, Sparling P F. Ability of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and commensal Neisseria species to obtain iron from transferrin and iron compounds. Infect Immun. 1981;33:555–564. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.2.555-564.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muralidharan K, Stern A, Meyer T F. The control mechanism of opacity protein expression in the pathogenic Neisseriae. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1987;53:435–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00415499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy G L, Connell T D, Barritt D S, Koomey M, Cannon J G. Phase variation of gonococcal protein II: regulation of gene expression by slipped-strand mispairing of a repetitive DNA sequence. Cell. 1989;56:539–547. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nachamkin I, Cannon J G, Mittler R S. Monoclonal antibodies against Neisseria gonorrhoeae: production of antibodies directed against a strain-specific cell surface antigen. Infect Immun. 1981;33:555–564. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.641-648.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parekh B S, Schwimmbeck P W, Buchmeier M J. High efficiency immunoaffinity purification of antipeptide antibodies on thiopropyl Sepharose immunoadsorbents. Peptide Res. 1989;2:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petterson A, Prinz T, van der Ley P, Poolman J T, Tommassen J. Characterization of the meningococcal lactoferrin receptor, abstr. P-221. In: Zollinger W, Frasch C, Deal C, editors. Abstracts of the Tenth International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference. 1996. p. 587. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prentki P, Krisch H M. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren Z, Jin H, Morton D J, Stull T L. Abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Cloning of hgpB, a gene encoding a second hemoglobin binding protein of Haemophilus influenzae, abstr. B-227; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rutz J M, Abdullah T, Singh S P, Kalve V I, Klebba P E. Evolution of the ferric enterobactin receptor in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5964–5974. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.5964-5974.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stern A, Brown M, Nickel P, Meyer T F. Opacity genes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: control of phase and antigenic variation. Cell. 1986;47:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90366-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stojiljkovic I, Hwa V, de Martin S L, O’Gaora P, Nassif X, Heffon F, So M. The Neisseria meningitidis hemoglobin receptor: its role in iron utilization and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:531–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stojiljkovic I, Larson J, Hwa V, Anic S, So M. HmbR outer membrane receptors of pathogenic Neisseria spp.: iron-regulated, hemoglobin-binding proteins with a high level of primary structure conservation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4670–4678. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4670-4678.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsai C M, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weinberg E D. Iron and infection. Microbiol Rev. 1978;42:45–66. doi: 10.1128/mr.42.1.45-66.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.West S E H, Sparling P F. Response of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to iron limitation: alterations in expression of membrane proteins without apparent siderophore production. Infect Immun. 1985;47:388–394. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.388-394.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.West S E H, Sparling P F. Aerobactin utilization by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and cloning of a genomic DNA fragment that complements Escherichia coli fhuB mutations. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3414–3421. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3414-3421.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]