Summary

Background

Gut probiotic depletion is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (NAFLD-HCC). Here, we investigated the prophylactic potential of Lactobacillus acidophilus against NAFLD-HCC.

Methods

NAFLD-HCC conventional and germ-free mice were established by diethylnitrosamine (DEN) injection with feeding of high-fat high-cholesterol (HFHC) or choline-deficient high-fat (CDHF) diet. Orthotopic NAFLD-HCC allografts were established by intrahepatic injection of murine HCC cells with HFHC feeding. Metabolomic profiling was performed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Biological functions of L. acidophilus conditional medium (L.a CM) and metabolites were determined in NAFLD-HCC human cells and mouse organoids.

Findings

L. acidophilus supplementation suppressed NAFLD-HCC formation in HFHC-fed DEN-treated mice. This was confirmed in orthotopic allografts and germ-free tumourigenesis mice. L.a CM inhibited the growth of NAFLD-HCC human cells and mouse organoids. The protective function of L. acidophilus was attributed to its non-protein small molecules. By metabolomic profiling, valeric acid was the top enriched metabolite in L.a CM and its upregulation was verified in liver and portal vein of L. acidophilus-treated mice. The protective function of valeric acid was demonstrated in NAFLD-HCC human cells and mouse organoids. Valeric acid significantly suppressed NAFLD-HCC formation in HFHC-fed DEN-treated mice, accompanied by improved intestinal barrier integrity. This was confirmed in another NAFLD-HCC mouse model induced by CDHF diet and DEN. Mechanistically, valeric acid bound to hepatocytic surface receptor GPR41/43 to inhibit Rho-GTPase pathway, thereby ablating NAFLD-HCC.

Interpretation

L. acidophilus exhibits anti-tumourigenic effect in mice by secreting valeric acid. Probiotic supplementation is a potential prophylactic of NAFLD-HCC.

Funding

Shown in Acknowledgments.

Keywords: Lactobacillus acidophilus, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma, Cancer prevention, Valeric acid, Rho-GTPase pathway

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The global incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (NAFLD-HCC) is rapidly increasing, but there is currently lack of preventive measure against its development. Recently, increasing evidence has revealed the close correlation between NAFLD-HCC and gut microbial dysbiosis with depletion of probiotics. However, the effect of probiotics in protecting against NAFLD-HCC is still largely unclear.

Added value of this study

We identified that Lactobacillus acidophilus is the top depleted bacterial species in NAFLD-HCC mice. L. acidophilus suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis in conventional mice induced by diet and carcinogen, and such protective effect is validated in orthoptic NAFLD-HCC allografts. The sole effect of L. acidophilus in inhibiting NAFLD-HCC tumourigenesis is confirmed in germ-free mice. We revealed that valeric acid is the functional metabolite of L. acidophilus identified by untargeted metabolomic profiling, and its upregulation in L. acidophilus-treated mice is verified by targeted metabolomics. Valeric acid exhibits protective function in bio-functional in vitro assays, and it also inhibited NAFLD-HCC in two tumourigenesis mouse models. Mechanistically, L. acidophilus-produced valeric acid directly binds to hepatocytic surface receptor GPR41/43 to inhibit the oncogenic Rho-GTPase pathway.

Implications of all the available evidence

L. acidophilus exhibits protective function against NAFLD-HCC tumourigenesis in mice by secreting valeric acid. Supplementation of L. acidophilus or other probiotics is therefore a potential prophylactic of NAFLD-HCC.

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease worldwide, affecting one billion individuals globally.1 NAFLD can gradually develop into more severe pathologies including non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cirrhosis, and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). To date, NAFLD has become the fastest growing aetiology of HCC.2 Compared to HCC caused by viral hepatitis, patients with NAFLD-associated HCC (NAFLD-HCC) have worse survival and poorer response to immunotherapy.3,4 The mechanism of NAFLD-HCC development is complex, while growing evidence has illustrated its close association with the gut microbiota. In humans, liver and intestine mutually communicate through the portal vein circulation to form the gut-liver axis.5 Notably, such interplay is dysregulated during hepatocarcinogenesis, as evidenced by the significant alteration in microbiota with enriched pathobionts in NAFLD-HCC patients.6,7 Hence, given by its importance, approaches to modulate the gut microbiota may yield preventive potential against NAFLD-HCC development.

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of probiotics as prophylactics against several types of cancer, and as adjuvants of cancer treatments to improve their efficacy.8,9 Probiotics also showed promising therapeutic potential against NAFLD and NASH,10 yet their role in NAFLD-HCC is unclear. In general, gut commensal probiotics were found to be depleted in NAFLD-HCC patients.7 Our previous study also reported the marked reduction of beneficial commensals including Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in NAFLD-HCC mice,11 thus suggesting the capacity of probiotic supplementation against NAFLD-HCC.

In this study, we identified that L. acidophilus is the top depleted bacterial species in mice with NAFLD-HCC. L. acidophilus exhibited robust anti-tumourigenic effects in vitro and in NAFLD-HCC mice. Through metabolomic profiling, valeric acid which is a type of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA), was found to be the key metabolite responsible for the protective function of L. acidophilus, and it could consistently suppress tumourigenesis in multiple NAFLD-HCC mouse models. Mechanistically, we revealed that L. acidophilus-derived valeric acid binds to G protein-coupled receptors (GPRs) to inactivate the oncogenic Rho-GTPase signalling pathway.

Methods

NAFLD-HCC mouse models

Male conventional C57BL/6 mice at 2 weeks old were intraperitoneally injected with a single dose of diethylnitrosamine (DEN; 25 mg/kg). At 6 weeks old, mice were randomised and daily gavaged with L. acidophilus (1 × 109 colony forming units resuspended in 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)), valeric acid (500 μM in PBS; sodium pentanoate, Aladdin, Shanghai, China), or PBS as negative control (n = 8–10 per group). Meanwhile, diet was changed from normal chow (NC) to high-fat high-cholesterol (HFHC) diet (43.7% fat, 36.6% carbohydrate, 19.7% protein, 0.203% cholesterol; #SF11-078, Specialty Feeds, Memphis, TN), or choline-deficient high-fat (CDHF) diet (60 kcal% fat, no choline; #D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) until sacrifice. HFHC-fed or CDHF-fed DEN-treated mice were sacrificed 28 weeks or 21 weeks after treatment, respectively. NC-fed mice without any treatment were set as model control.

Germ-free mouse model

Male germ-free C57BL/6 mice at 2 weeks old were intraperitoneally injected with a single dose of DEN. At 6 weeks old, mice were fed with HFHC diet and randomised to receive L. acidophilus or PBS on every other day (n = 10–12 per group). Mice were sacrificed 34 weeks after treatment.

Orthotopic NAFLD-HCC allograft

Male conventional C54BL/6 mice were fed with HFHC diet. At 15 weeks old, mice were randomised and daily gavaged with L. acidophilus or PBS (n = 6 per group). Murine HCC cell line Hepa 1–6 was resuspended (1 × 105 cells/μL) in PBS mixed with Matrigel (Corning, Corning, NY) at a ratio of 1:1, then injected into the left liver lobe of mouse at 18 weeks old (10 μL per mouse). Mice were sacrificed 3 weeks after injection. Bioluminescent imaging was performed weekly to monitor tumour growth by intraperitoneal injection of D-luciferin (150 mg/kg per mouse; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), followed by image capture using IVIS Spectrum In Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer). Liver, intestines, stools, portal vein blood, and whole blood were collected from all mice at sacrifice. All animal studies were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committees of The Chinese University of Hong Kong for conventional mice, and Sun Yat-sen University for germ-free mice. Sample sizes of all animal experiments were pre-determined and checked by the statisticians of the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committees of The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Bacteria culture

L. acidophilus was purchased from The Leibniz Institute (#DSM 20079, Braunschweig, Germany). Escherichia coli strain MG1655 which is a non-pathogenic bacterium in the human gut, was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (#ATCC 700926, Manassas, VA) and used as bacterial control. L. acidophilus and E. coli were cultured in MRS broth mixed with Brain Heart Infusion broth at a ratio of 1:1 in a shaking incubator at 37 °C under aerobic condition. When the optical density (OD) at 600 nm reached 0.5, the conditional medium of L. acidophilus (L.a CM) was collected by centrifugation at 4000×g for 10 min and purification by filters with a pore size of 0.22 μm. To characterise the molecules in L.a CM, it was either heated at 100 °C for 30 min or treated with proteinase K (50 μg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with incubation at 55 °C for 30 min then at 95 °C for 10 min. L.a CM with greater or less than 3 kDa was obtained by centrifugation at 4000×g for 30 min using Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Unit (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA).

Metabolite extraction

For untargeted metabolomic profiling, 50 μL of bacterial conditional medium was mixed with 500 μL of extraction solution (methanol-to-water = 3:1) containing an isotope-labelled internal standard. Sample mixtures were ultrasonicated in ice water and incubated at −40 °C for 60 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min and supernatants were collected. The quality control sample was prepared by mixing an equal volume of supernatants from all samples.

For targeted detection of SCFAs, a modified extraction protocol with derivatisation was required.12 50 μL of bacterial conditional medium or mouse portal vein serum was added to 200 μL of methanol containing an internal standard (4-chlorophenol, 1 μg/mL). For mouse liver tissues and stools, 20 mg of samples was added to 200 μL of extraction solution (acetonitrile-to-methanol-to-water = 4:4:2) with the internal standard. After homogenisation, 80 μL of sample mixtures was vacuum dried for 2 h and then derivatised by adding 40 μL of 3-nitrophenylhydrazine hydrochloride and 40 μL of N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride, with incubation at 40 °C for 30 min. Upon centrifugation at 20,000×g for 10 min, 90 μL of supernatants was collected and transferred to a fresh glass vial for liquid-chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

LC-MS and metabolite annotation

LC-MS was performed by TSQ Altis Plus Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer, coupled with Vanquish Flex UHPLC System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Chromatography separation was conducted using ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.8 μm; Waters, Milford, MA). The auto-sampler temperature was 4 °C, and the injection volume was 2 μL. MS/MS spectra were acquired on information-dependent acquisition mode in the acquisition software (Xcalibur, version 4.2 SP1). The ESI source conditions were set as following: sheath gas flow rate = 50 Arb; aux gas flow rate = 15 Arb; capillary temperature = 320 °C; full MS resolution = 60,000; MS/MS resolution = 15,000; collision energy = 10/30/60 in NCE mode; spray voltage = 3.8 kV (positive) or −3.4 kV (negative).

Raw data were converted to mzXML format using ProteoWizard (version 3.0.21229) and processed by XCMS (version 3.2). R package CAMERA (version 3.16) was used for peak annotation. Peaks with relative standard deviation >30% in quality control samples, or peaks with missing value (intensity = 0) in >50% of samples, were discarded. Only matched MS and MS/MS spectra were included for metabolite annotation. The filtered MS/MS spectra were assessed by Human Metabolome Database, METLIN metabolite database, and an in-house database to characterise metabolites. Metabolites with MS2 score >0.8 were included for subsequent analysis, with a total of 652 annotated MS/MS features. Metabolites in L.a CM with P < 0.05 when compared to both broth control and E. coli conditional medium (E. coli CM), were considered statistically differential (Supplementary Table S1).

RNA sequencing and analysis

Total RNA extracted from cell line HKCI-2 was subjected to RNA sequencing (Illumina NovaSeq 6000 Sequencing System) performed by Novogene (Beijing, China). TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) was used for the construction of sequencing library. Data were presented as reads per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped (RPKM). Sequencing reads were preceded by removing adapters using cutadapt (version 1.18) and mapped on the reference human genome (GENCODE version 30) by HISAT2 (version 2.1.0) with the default options. The number of reads mapped to each single gene was counted by HTSeq (version 0.11.2) with the option “−m 1 intersection-nonempty”. Gene expression levels were calculated as fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKM) by DESeq2 (version 3.16). Differentially expressed genes (log2 fold change ≥2, −log(P) ≥ 10) were included for functional analysis using GO, KEGG, and Reactome pathway databases (Supplementary Table S2).

Statistical analyses

All results are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the difference in numerical variables between two groups unless specified. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the difference in numerical variables among three groups. Repeated measures two-way ANOVA was used to compare different timepoints or stages between two groups. Categorical variables between two groups were compared by Fisher’s exact test. All statistical analyses were performed and plotted using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0) or R language. Two-tailed P value smaller than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Role of funders

The funding source did not have any role in study design, data collection, data analyses, interpretation, or writing of report.

Additional methods are provided in Supplementary Information.

Results

L. acidophilus suppresses NAFLD-HCC development in tumourigenesis mouse model

Given that the gut microbiota is closely associated with NAFLD-HCC, we first characterised microbial alteration in NAFLD-HCC mice. Based on faecal metagenomic sequencing, L. acidophilus was identified as one of the top depleted species in mice with NAFLD-HCC induced by HFHC diet, compared to control mice (Fig. 1A). For confirmation, additional differential analyses including LEfSe, MetaStat, and random forest, were performed, and all these tests consistently showed that L. acidophilus was among the top depleted species in mice with NAFLD-HCC (Supplementary Table S3). This result suggested the potentially beneficial role of L. acidophilus in NAFLD-HCC development.

Fig. 1.

L. acidophilus suppresses NAFLD-HCC development in tumourigenesis mouse model. (A) Heatmap of faecal metagenomic sequencing on NAFLD-HCC mice showing differential microbes (arranged by relative abundance). Differential analysis was performed by comparing HFHC-fed mice (n = 10) to HFLC-fed mice (n = 8) using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (B) Experimental schematic of HFHC-fed DEN-treated mice and representative images of liver tumours (10 mice per group). Mice without any treatment (NC) were compared to HFHC-fed DEN-treated mice with PBS control to confirm the establishment of NAFLD-HCC mouse model. (C) Measurement of tumour parameters. (D) Representative H&E images and histological scoring of non-tumour liver tissues. (E) Measurement of serum makers. (F) Representative Ki-67 images and scoring of liver tissues. HFLC, high-fat low-cholesterol; L.a, L. acidophilus; NC, normal chow; NT, non-tumour; T, tumour. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

We therefore treated a NAFLD-HCC mouse model induced by carcinogen (DEN) and HFHC diet with daily administration of L. acidophilus or PBS control. Upon 28 weeks of treatment, mice were sacrificed and macroscopic tumours were observed in the liver of all HFHC-fed mice (Fig. 1B and C). Of note, L. acidophilus supplementation significantly reduced tumour number, tumour size, and tumour load compared with control (all P < 0.05), whereas it had no effects on tumour incidence (Fig. 1C). Histological assessment identified the marked reduction of steatosis and inflammation in the non-tumour liver tissues of L. acidophilus-treated mice (both P < 0.05; Fig. 1D). Consistently, serum levels of liver damage markers alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) as well as cholesterol were significantly decreased in L. acidophilus-treated mice (all P < 0.05; Fig. 1E), while there were no differences in body weight and liver weight compared with control (Supplementary Figure S1A). Moreover, the proportion of proliferating cells was lowered by L. acidophilus supplementation (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1F). These findings thus demonstrated the anti-tumourigenic effect of L. acidophilus on NAFLD-HCC.

L. acidophilus suppresses NAFLD-HCC development in orthotopic allografts

For verification, we established an orthotopic NAFLD-HCC allograft model by injecting a murine HCC cell line (Hepa 1–6) into the liver of conventional mice fed with HFHC diet (Fig. 2A). In line with the tumourigenesis mouse model, smaller liver tumours were observed in L. acidophilus-treated mouse allografts (Fig. 2B), with significantly reduced tumour weight and tumour volume (both P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). Moreover, the abundance of L. acidophilus was markedly enriched in gavaged mice, hence confirming that L. acidophilus supplementation was successful (Supplementary Figure S1B). Together, our consistent findings of different mouse models confirmed the protective effect of L. acidophilus against NAFLD-HCC development.

Fig. 2.

L. acidophilus suppresses NAFLD-HCC development in orthotopic allografts and germ-free mice. (A) Experimental schematic of orthotopic NAFLD-HCC allografts and bioluminescent imaging of tumours (6 mice per group). (B) Macroscopic pictures and representative H&E images of liver tumours. (C) Measurement of tumour parameters. (D) Experimental schematic of HFHC-fed DEN-treated germ-free mice and representative images of liver tumours (PBS, n = 8; L.a, n = 10). (E) Measurement of tumour parameters. (F) Representative H&E images and histological scoring of non-tumour liver tissues. (G) Measurement of serum markers. (H) Representative Ki-67 images and scoring of liver tissues. L.a, L. acidophilus; NT, non-tumour; T, tumour. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

L. acidophilus enriches probiotics and depletes pathobionts in NAFLD-HCC mice

Since probiotics could confer benefits against liver disease by modulating microbiota,13 we evaluated the impact of L. acidophilus on the gut microbiota by performing faecal metagenomic sequencing. Interestingly, the results showed that there were no differences in α-diversity (Shannon and Chao1; Supplementary Figure S1C) and β-diversity (Supplementary Figure S1D) between L. acidophilus-treated and untreated control mice, implicating that L. acidophilus has insignificant effect on the overall microbiota composition. Meanwhile, significantly altered microbes were identified by differential analysis, and the result confirmed the enrichment of L. acidophilus in gavaged mice (Supplementary Figure S1E). Several well-characterised probiotics such as Romboutsia and Bacteroides cellulosilyticus were also enriched in L. acidophilus-treated mice, accompanied with the depletion of opportunistic pathobionts including Burkholderia cenocepacia and Micrococcus luteus. To validate in silico results, we cultured several well-studied probiotics including Bifidobacterium pseudolongum and Lactobacillus gallinarum with L.a CM, and the result showed that L.a CM directly promoted the growth of these probiotics in a concentration-dependent manner (Supplementary Figure S1F). Collectively, although the overall gut microbiota was unaffected by L. acidophilus, it could elevate the abundance of commensal probiotics while reducing potential pathobionts.

L. acidophilus suppresses NAFLD-HCC development in germ-free mice

To testify the sole beneficial effect of L. acidophilus, we supplemented L. acidophilus to germ-free mice with NAFLD-HCC induced by DEN and HFHC diet. Macroscopic liver tumours were observed upon 34 weeks of treatment (Fig. 2D). L. acidophilus significantly reduced tumour number (P < 0.01), tumour size (P < 0.01), and tumour load (P < 0.001) compared with untreated control, whereas it had no effects on tumour incidence (Fig. 2E). Histological assessment identified the reduction of steatosis (P < 0.05) in the non-tumour liver tissues of L. acidophilus-treated mice (Fig. 2F). Serum levels of ALT, AST, and cholesterol were also significantly decreased in L. acidophilus-treated mice (all P < 0.05; Fig. 2G), accompanied with lowered body weight (P < 0.05) and liver weight (P < 0.01) (Supplementary Figure S1G). Moreover, the proportion of proliferating cells was markedly reduced by L. acidophilus supplementation (P < 0.01; Fig. 2E). In addition, the abundance of L. acidophilus was markedly enriched in gavaged mice, thus confirming the success of L. acidophilus supplementation (Supplementary Figure S1H). Hence, these findings indicated that L. acidophilus alone is adequate to suppress NAFLD-HCC in mice with a depleted microbiota.

L. acidophilus secretes non-protein small molecules against NAFLD-HCC

The anti-tumourigenic mechanism of L. acidophilus was investigated. While L. acidophilus was enriched in mouse stools following oral gavage, it was undetected in the liver of L. acidophilus-treated mice (Supplementary Figure S2A). Through fluorescence in situ hybridisation, L. acidophilus was found to be highly expressed in the colon but absent in liver tissues of gavaged mice (Supplementary Figure S2B). These results suggested that the protective effect of L. acidophilus was attributed to its secreted molecules but not the bacteria itself. We therefore co-cultured two human NAFLD-HCC cell lines HKCI-2 and HKCI-10 with L.a CM. The result showed that L.a CM suppressed the viability of NAFLD-HCC cells in a concentration-dependent manner, but no effect on human normal hepatocytes MIHA (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Figure S2C). Consistently, the growth of tumour organoids derived from NAFLD-HCC mice was significantly reduced by L.a CM (P < 0.0001), whereas organoids derived from mouse normal hepatocytes were unaffected (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

L. acidophilus secretes non-protein small molecules against NAFLD-HCC. (A) Cell viability at OD570 of human NAFLD-HCC (HKCI-2, HKCI-10) or normal hepatocyte (MIHA) cell lines treated with bacterial conditional medium. (B) Representative images and size of mouse organoids after treatment. Scale bar = 100 μm. (C) Cell viability at OD570 after treatment of heated conditional medium. (D–H) Cell viability at OD570(D), colony formation assay (E), Ki-67 immunofluorescent staining with a scale bar of 25 μm (F), cell apoptosis assay (G), and cell cycle assay (H) after treatment of conditional medium with different molecular weights. (I) Western blot of protein markers related to cell proliferation and apoptosis. The used concentration of conditional medium was 7.5% in cell culture medium. P values in (A, C) were calculated by comparing L.a CM (A) or L.a CM <3 kDa (C) to every other groups using repeated measures two-way ANOVA.∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Bacteria can secrete various molecules including proteins and metabolites. We found that the inhibitory effect of L.a CM still existed after it was heated or treated with proteinase K, indicating that the molecules responsible for L. acidophilus to exhibit protective effect were not proteins (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Figure S2D and E). Next, we separated L.a CM into different fractions based on the molecular weight, and revealed that only L.a CM with less than 3 kDa could suppress growth (Fig. 3D) and proliferation (Fig. 3E and F) of NAFLD-HCC cells. Significantly elevated apoptosis was also observed in NAFLD-HCC cells co-cultured with L.a CM with <3 kDa (Fig. 3G). Moreover, the treatment of L.a CM with <3 kDa led to cell cycle arrest in NAFLD-HCC cells with a marked increase in cells at G0/G1 phase and a concomitant decrease in cells at synthesis phase (Fig. 3H). These results were confirmed by Western blot, which showed consistent changes in the expression of protein markers related to proliferation and apoptosis including Caspase-3, Parp, and Pcna (Fig. 3I). Collectively, our findings implied that the anti-tumorigenic effect of L. acidophilus is attributed to its non-protein small molecules with a molecular weight of <3 kDa.

Valeric acid is the major metabolite produced by L. acidophilus

To characterise the functional molecules of L. acidophilus, we performed untargeted metabolomic profiling by LC-MS on L.a CM with <3 kDa. Our analysis revealed that the metabolomic profile was distinct between L.a CM and controls (Fig. 4A). Among the differential metabolites, valeric acid which is a type of SCFA, was the top enriched metabolite in L.a CM compared to broth control and E. coli CM (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Table S1). Targeted metabolomics was then conducted to specifically detect SCFAs, and the result confirmed the significant enrichment of valeric acid in L.a CM (P < 0.01; Fig. 4C). We also examined the level of valeric acid in HFHC-fed DEN-treated conventional mice, and identified its marked increase in liver and portal vein serum after L. acidophilus supplementation (both P < 0.05; Fig. 4D). Similarly, valeric acid was significantly enriched in liver (P < 0.01) and portal vein serum (P < 0.05) of HFHC-fed DEN-treated germ-free mice with L. acidophilus supplementation (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Valeric acid is the major metabolite produced by L. acidophilus. (A) Principal component analysis on the metabolomic profile of bacterial conditional medium. (B) Heatmap of differentially enriched metabolites in L.a CM compared to broth control and E. coli CM. (C) Level of major SCFAs in bacterial conditional medium detected by targeted metabolomics. (D, E) Valeric acid level in liver and portal vein serum of HFHC-fed DEN-treated conventional (10 mice per group) (D) or germ-free (PBS, n = 8; L.a, n = 10) (E) mice. L.a, L. acidophilus; VA, valeric acid. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

Given that L. acidophilus is a well-acknowledged SCFA-producing bacteria,14 we also examined the levels of other major SCFAs in L.a CM and in mice. Indeed, acetate (P < 0.01) and propanoate (P < 0.05) were enriched in L.a CM compared to broth control, while no significant change was observed for butyrate (Fig. 4C). Notably, none of these SCFAs was significantly changed among liver and portal vein serum of HFHC-fed DEN-treated conventional (Supplementary Figure S3A and B) and germ-free (Supplementary Figure S3C and D) mice, except for valeric acid. These findings thus suggested that valeric acid is the major metabolite of L. acidophilus to protect against NAFLD-HCC.

Valeric acid exhibits protective function against NAFLD-HCC in vitro

The role of valeric acid was tested in human NAFLD-HCC cells. Valeric acid suppressed the viability of NAFLD-HCC cells but not normal hepatocytes in a concentration-dependent manner, with 100 μM being the minimal significant concentration (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Figure S4A). Such inhibitory effect was not attributed to the cytotoxicity induced by exposure to excess valeric acid (Supplementary Figure S4B). Similarly, the growth of tumour organoids derived from NAFLD-HCC mice was significantly reduced by valeric acid (P < 0.0001), whereas organoids derived from mouse normal hepatocytes remained unaffected (Fig. 5B). The proliferation of NAFLD-HCC cells was suppressed after valeric acid treatment, as indicated by colony formation (Fig. 5C) and Ki-67 immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 5D). Significantly elevated apoptosis was also observed in NAFLD-HCC cells treated with valeric acid (Fig. 5E). Moreover, valeric acid treatment led to cell cycle arrest with a marked increase in cells at G0/G1 phase and a concomitant decrease in cells at synthesis phase (Fig. 5F). These results were confirmed by Western blot, which showed consistent changes in the expression of protein markers related to proliferation (Pcna), apoptosis (Caspase-3, Parp), and cell cycle (Cyclin D1) (Fig. 5G). Collectively, our findings implicated the protective function of valeric acid against NAFLD-HCC.

Fig. 5.

Valeric acid exhibits protective function against NAFLD-HCC in vitro. (A) Cell viability at OD570 of human NAFLD-HCC (HKCI-2, HKCI-10) or normal hepatocyte (MIHA) cell lines after treatment of valeric acid for 3 days. P values were calculated by comparing each valeric acid concentration to vehicle control (0 μM) using repeated measures two-way ANOVA. (B) Representative images and size of mouse organoids after treatment. Scale bar = 100 μm. (C–G) Colony formation assay (C), Ki-67 immunofluorescent staining with a scale bar of 25 μm (D), cell apoptosis assay (E), and cell cycle assay (F) after treatment. (G) Western blot of protein markers related to cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle. The used concentration of valeric acid was 500 μM. VA, valeric acid. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Valeric acid suppresses NAFLD-HCC development in tumourigenesis mouse models

We next examined the effect of valeric acid in mice with NAFLD-HCC induced by DEN and HFHC diet. Macroscopic tumours were observed in the liver of all mice upon 28 weeks of treatment (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Figure S5A). As expected, the level of valeric acid was increased in stool (P < 0.05), liver (P < 0.0001), and portal vein serum (P < 0.001) of mice with valeric acid supplementation (Supplementary Figure S5B). Of note, valeric acid significantly reduced tumour number (P < 0.05), tumour size (P < 0.01), and tumour load (P < 0.05) compared with control (Fig. 6B). Histological assessment reported the marked reduction of steatosis and inflammation in the non-tumour liver tissues of valeric acid-treated mice (both P < 0.05; Fig. 6C). Serum levels of ALT, AST, and cholesterol were also significantly decreased in valeric acid-treated mice (all P < 0.05; Fig. 6D), while there were no differences in body weight and liver weight compared with control (Supplementary Figure S5C). Moreover, the proportion of proliferating cells was lowered by valeric acid treatment (P < 0.001; Fig. 6E), implying the anti-tumourigenic role of valeric acid in NAFLD-HCC.

Fig. 6.

Valeric acid suppresses NAFLD-HCC development in tumourigenesis mouse models. (A) Experimental schematic of HFHC-fed DEN-treated mice and representative images of liver tumours (10 mice per group). (B) Measurement of tumour parameters. (C) Representative H&E images and histological scoring of non-tumour liver tissues. (D) Measurement of serum markers. (E) Representative Ki-67 images and scoring of liver tissues. (F) Experimental schematic of CDHF-fed DEN-treated mice and representative images of liver tumours (PBS, n = 12; valeric acid, n = 10). (G) Measurement of tumour parameters. (H) Representative H&E images and histological scoring of non-tumour liver tissues. (I) Measurement of serum markers. (J) Representative Ki-67 images and scoring of liver tissues. NT, non-tumour; T, tumour; VA, valeric acid. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

For verification, we established another mouse model of NAFLD-HCC induced by DEN and CDHF diet with daily supplementation of valeric acid. Macroscopic liver tumours were observed upon 21 weeks of treatment (Fig. 6F). Although tumours were developed in all mice (Supplementary Figure S5D), valeric acid significantly reduced tumour size and tumour load compared with control (both P < 0.05; Fig. 6G). The enrichment of valeric acid in mouse stool (P < 0.05), liver (P < 0.0001), and portal vein serum (P < 0.001) of mice with valeric acid supplementation was confirmed by targeted metabolomics (Supplementary Figure S5E). Histological assessment identified the marked reduction of steatosis and inflammation in the non-tumour liver tissues of valeric-acid treated mice (both P < 0.01; Fig. 6H). Serum levels of ALT, AST, and cholesterol were also significantly decreased in valeric acid-treated mice (all P < 0.05; Fig. 6I), accompanied with lowered body weight and liver weight (both P < 0.05; Supplementary Figure S5F). Moreover, the proportion of proliferating cells was markedly reduced by valeric acid treatment (P < 0.01; Fig. 6J). Together, our consistent findings of two mouse models confirmed the protective function of valeric acid against NAFLD-HCC development.

Valeric acid improves intestinal barrier integrity in NAFLD-HCC mice

Given that an impaired barrier is a prerequisite for NAFLD-HCC development,15 we further assessed the integrity of intestinal barrier in mice. Our result revealed that the function of intestinal barrier was improved by valeric acid, as indicated by the decreased efflux of FITC-labelled dextran in mouse serum (Supplementary Figure S5G). The endotoxemia marker lipopolysaccharides (LPS) was also significantly decreased in valeric acid-treated mice compared to control (Supplementary Figure S5H). Similarly, colonic mRNA and protein expressions of intestinal barrier markers including Claudins, E-cadherin, and Zo-1 were greatly downregulated after valeric acid treatment (Supplementary Figure S5I and J). Hence, these findings suggested that valeric acid could improve the integrity and function of intestinal barrier in NAFLD-HCC mice.

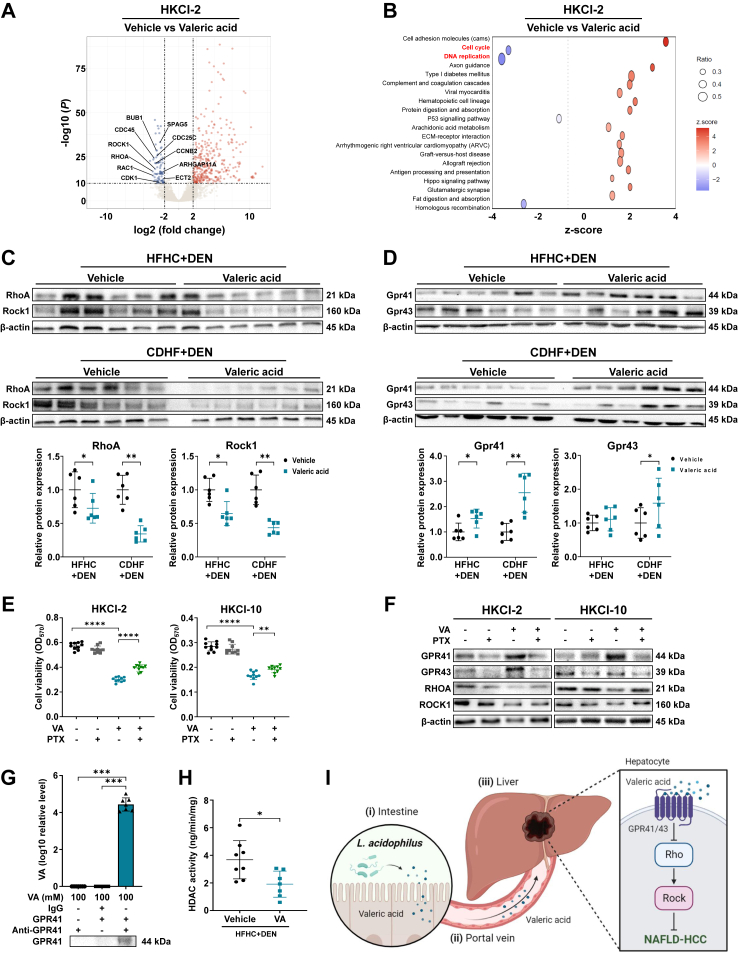

Valeric acid inhibits oncogenic Rho-GTPase signalling pathway

To decipher the underlying mechanism, RNA sequencing was conducted on NAFLD-HCC cells (HKCI-2) with or without valeric acid treatment. Our analysis identified 451 differentially upregulated and 81 downregulated genes in valeric acid-treated cells compared to vehicle control (Supplementary Figure S6A and Supplementary Table S2). Of note, the expression of genes related to Rho-GTPase pathway including its major activators RHOA, RAC1, and ROCK1 as well as its downstream targets was significantly reduced by valeric acid (Fig. 7A and Supplementary Figure S6B). Rho-GTPase signalling is known to promote cancer initiation and progression by manipulating proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle in tumour cells.16 Consistently, pathway analysis revealed the marked downregulation of cell cycle and DNA replication in NAFLD-HCC cells treated with valeric acid (Fig. 7B). Moreover, hepatic mRNA (Supplementary Figure S6C and D) and protein (Fig. 7C) expressions of RhoA, Rock1, and other Rho-GTPase pathway markers were decreased in valeric acid-treated mice, as well as in L. acidophilus-treated mice (Supplementary Figure S6E and F). These findings implicated that valeric acid could suppress Rho-GTPase signalling.

Fig. 7.

Valeric acid binds to hepatocytic surface receptor GPR41/43 to inhibit oncogenic Rho-GTPase signalling pathway. (A) Volcano plot of differential genes (log2 fold change ≥2, −log(P) ≥ 10) in HKCI-2 cell line with or without valeric acid treatment. Top depleted genes related to Rho-GTPase pathway are indicated. (B) Pathway analysis of differential genes. (C, D) Hepatic protein expression of markers related to Rho-GTPase pathway (C) or GPRs (D) in mice. (E) Cell viability at OD570 of human NAFLD-HCC (HKCI-2, HKCI-10) cell lines after treatment of valeric acid and/or PTX for 3 days. (F) Protein expression in cells treated with valeric acid and/or PTX. (G) Direct pull-down assay of valeric acid using GPR41 recombinant proteins. (H) Hepatic HDAC activity in HFHC-fed DEN-treated mice. (I) Overview schematic of the study (created by BioRender.com). The used concentration of valeric acid was 500 μM. VA, valeric acid. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Valeric acid binds to hepatocytic surface receptor GPR41/43 to inhibit Rho-GTPase pathway

We next investigated how valeric acid inactivated Rho-GTPase pathway. GPR41, GPR43, and GPR109a are the major receptors of SCFAs in the liver.17 Our result showed that the mRNA expression of Gpr41 and Gpr43 but not Gpr109a was significantly upregulated in the liver of valeric acid-treated mice (Supplementary Figure S6G). Hepatic protein expression of Gpr41 and Gpr43 was also markedly increased by valeric acid (Fig. 7D). Consistently, the mRNA expression of Gpr41 and Gpr43 was significantly upregulated in the liver of L. acidophilus-treated (Supplementary Figure S6H). For validation, we blocked GPR41 and GPR43 in vitro using pertussis toxin (PTX) which is an antagonist of GPRs.18 The use of GPR blocker abolished the protective effect of valeric acid on NAFLD-HCC cells, as indicated by the increase in cell viability (Fig. 7E) and the upregulation of Rho-GTPase pathway markers (Fig. 7F). We further confirmed that valeric acid could directly bind to GPR41 by pull-down assay (Fig. 7G). In addition, the activity of histone deacetylase (HDAC) was significantly inhibited by valeric acid in mouse liver (P < 0.05; Fig. 7H) and in NAFLD-HCC cells (Supplementary Figure S6I), in line with a previous study.19 Altogether, our findings illustrated that L. acidophilus-derived valeric acid binds to surface receptor GPR41/43 on hepatocytes to inactivate oncogenic Rho-GTPase signalling pathway, thereby ablating NAFLD-HCC development (Fig. 7H).

Discussion

In this study, we identified that L. acidophilus supplementation suppresses NAFLD-HCC development in tumourigenesis mouse models. The role of gut microbiota in NAFLD-HCC is now increasingly acknowledged. In particular, the occurrence of gut dysbiosis together with the depletion of commensal probiotics was reported in human patients and mice.7,11 Through faecal metagenomic sequencing, we identified that L. acidophilus is the top depleted bacteria in NAFLD-HCC mice (Fig. 1). L. acidophilus is a well-known gram-positive probiotic species which has been widely commercialised as an oral supplement against various diseases including colitis and lactose intolerance.20 Several studies also revealed the feasibility of L. acidophilus supplementation against NAFLD and NASH in human patients and in mouse models.21,22 Here, we for the first time discovered the anti-tumourigenic effect of L. acidophilus against NAFLD-HCC in mice, suggesting the potential of probiotic administration against the development of liver malignancy.

Our results showed that L. acidophilus supplementation inhibits NAFLD-HCC development in mice with reduced tumour growth. Alleviated steatosis and necro-inflammation which are two crucial factors of NAFLD-HCC development,23 were also observed in L. acidophilus-treated mice, consistent with previous studies reporting the anti-steatosis and anti-inflammatory features of L. acidophilus.20,24 Faecal metagenomic sequencing analysis further identified the enrichment of commensal probiotics such as Romboutsia and B. cellulosilyticus as well as the depletion of opportunistic pathobionts including B. cenocepacia and M. luteus,25 in L. acidophilus-treated mice. We also observed that the growth of several well-studied probiotics including L. gallinarum and B. pseudolongum which could also suppress NAFLD-HCC in mice,26 was markedly increased after L.a CM treatment. Notably, L. acidophilus was capable of suppressing tumourigenesis in NAFLD-HCC germ-free mice (Fig. 2). These results collectively indicated that L. acidophilus alone is sufficient to exhibit anti-tumourigenic effect in microbiota-depleted mice, meanwhile it could modulate other gut microbial components in mice with an intact microbiota. Together, our findings illustrate the prophylactic potential of L. acidophilus against NAFLD-HCC development in mice.

Given the absence of L. acidophilus in liver tissues of gavaged mice, we hypothesised that it may secrete several molecules in the intestines, which are then translocated to the liver through the portal vein circulation to exhibit protective function. Probiotics could produce different kinds of molecules to confer health benefits including proteins and metabolites.9,27 A previous study also reported the anti-inflammatory role of extracellular polysaccharides derived from L. acidophilus to alleviate liver tumourigenesis in rats.28 In this study, we found that the inhibitory effect of L.a CM still exists after it was heated or treated with proteinase, whereas only L.a CM with a molecular weight of less than 3 kDa has protective effects against NAFLD-HCC in bio-functional assays (Fig. 3). These findings collectively imply that the functional molecules of L. acidophilus are non-protein small molecules.

As molecules with a molecular weight of less than 3 kDa are most likely metabolites, we therefore conducted untargeted metabolomic profiling on bacterial conditional medium. Our analysis identified the significant enrichment of SCFAs in L.a CM (Fig. 4), in line with previous studies reporting that L. acidophilus is a SCFA-producing bacteria.29 For verification, targeted metabolomics was performed and the result confirmed the significant upregulation of SCFAs in L.a CM and in L. acidophilus-treated mice. In general, SCFAs are produced from microbes-mediated fermentation of dietary fibres, and they are pivotally involved in metabolism of liver and adipose tissues.30 Many studies have demonstrated the anti-tumourigenic role of SCFAs against cancer.27 For example, SCFA supplementation could delay the progression from chronic liver disease to HCC in transgenic mice,31 whilst the combination of acetate with immune checkpoint blockade markedly improves anti-tumour immunity.32 In humans, a recent study identified a significant depletion of butyrate in HCC patients compared to healthy individuals, while butyrate supplementation could improve the efficacy of targeted therapy.33 Of note, among all major SCFAs, only valeric acid was consistently enriched in L.a CM and in mouse liver and portal vein serum, implicating its translocation from the intestine to the liver (Supplementary Figure S3). Hence, valeric acid was selected as the key functional metabolite of L. acidophilus for investigation. Nevertheless, given the well-studied beneficial role of SCFAs against various diseases and cancer, other SCFAs apart from valeric acid may also contribute to the anti-tumourigenic effect of L. acidophilus, even though they were not consistently enriched among all samples.

The role of valeric acid in NAFLD-HCC was examined by in vitro bio-functional assays. As expected, valeric acid significantly supressed the growth of human NAFLD-HCC cells and mouse tumour organoids (Fig. 5). Our results also demonstrated that valeric acid could reduce proliferation and induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in NAFLD-HCC cells. We then validated our in vitro findings in two NAFLD-HCC mouse models, and the results showed that valeric acid supplementation greatly ablates tumourigenesis in these mice (Fig. 6). Moreover, an impaired intestinal barrier is a prerequisite for NAFLD-HCC development,15 whereas valeric acid could improve its integrity, as observed by the upregulation of intestinal barrier markers (E-cadherin, Claudins) in colon and reduced level of endotoxemia marker LPS in portal vein of mice (Supplementary Figure S5). Together, our in vitro and in vivo observations confirmed the protective function of valeric acid against NAFLD-HCC.

Our transcriptomic analysis identified that multiple genes related to cell cycle (BUB1, CDC25C, CDC45, CDK1) and Rho-GTPase pathway (RHOA, RAC1, ROCK1) are markedly downregulated in mouse liver and NAFLD-HCC cells after valeric acid treatment (Fig. 7). In general, Rho-GTPase pathway contributes to cancer initiation and development by promoting proliferation and mediating metabolism and stemness of tumour cells, as well as facilitating the establishment of a pro-inflammatory tumour microenvironment.16 We then examined how valeric acid interacts with hepatocytes. GPRs especially GPR41 and GPR43 are known to be the major receptors of SCFAs,17 whereas GPR41 has higher binding affinity with valeric acid than GPR43.34 Indeed, we identified that hepatic expressions of Gpr41 and Gpr43 are significantly upregulated in mice after valeric acid supplementation. Once GPR inhibitor (PTX) was used, the anti-tumourigenic effect of valeric acid was lost, accompanied with the upregulation of Rho-GTPase pathway. These findings thus confirm that valeric acid exhibits protective function against NAFLD-HCC via binding to GPR41/43 on hepatocytes, thereby suppressing the oncogenic Rho-GTPase pathway. In addition, dysregulated activation of HDAC, the major epigenetic mediator of histone modification, is known to be pro-tumourigenic and many studies have reported the use of HDAC inhibitors against HCC.35 Here, we showed that valeric acid markedly constrains hepatic HDAC activity of NAFLD-HCC mice, consistent with a study reporting that valeric acid could act as HDAC inhibitor against hepatocarcinogenesis.19

In summary, here we found that L. acidophilus supplementation significantly ablates NAFLD-HCC tumourigenesis in conventional and germ-free mice. Through untargeted and targeted metabolomics, our results implied that gut L. acidophilus secretes SCFAs particularly valeric acid, which are then translocated to the liver to exhibit protective function. Valeric acid exhibits anti-tumourigenic effects in vitro and in vivo, of which it could bind to surface receptor GPR41/43 on hepatocytes to inactivate oncogenic pathways. Overall, L acidophilus supplementation is a potential prophylactics against NAFLD-HCC development. Further clinical investigation is warranted to confirm its feasibility to alleviate the progression from NASH to liver malignancy in human patients.

Contributors

HCHL designed the study, performed the experiments, and drafted the manuscript. XZ designed the study and revised the manuscript. FJ performed the experiments and conducted metabolomic analyses. YL and WLiu conducted bioinformatic analyses. WLiang, QL, DC, WF, XK, ESHC, and QWYN performed the experiments. JY designed and supervised the study and revised the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Data is available within the article and its Supplementary Materials. The raw data of mouse faecal metagenomic sequencing have been deposited under the accession number PRJNA1036364 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1036364).

Declaration of interests

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Li Ka Shing Foundation for supporting the Li Ka Shing Translational Omics Platform.

Funding: This study was supported by RGC Theme-based Research Scheme (T12-703/19-R), RGC Research Impact Fund (R4017-18F; R4032-21F), Health and Medical Research Fund (07210097, 08191336), Research Grants Council-General Research Fund (14117123, 14117422), RGC Collaborative Research Fund (C4039-19GF), Vice-Chancellor’s Discretionary Fund CUHK (4930775), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82103355, 82222901, 82272619).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104952.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Powell E.E., Wong V.W., Rinella M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet. 2021;397:2212–2224. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang D.Q., El-Serag H.B., Loomba R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:223–238. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfister D., Nunez N.G., Pinyol R., et al. NASH limits anti-tumour surveillance in immunotherapy-treated HCC. Nature. 2021;592:450–456. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03362-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foerster F., Gairing S.J., Muller L., et al. NAFLD-driven HCC: safety and efficacy of current and emerging treatment options. J Hepatol. 2022;76:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tripathi A., Debelius J., Brenner D.A., et al. The gut-liver axis and the intersection with the microbiome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:397–411. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aron-Wisnewsky J., Vigliotti C., Witjes J., et al. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:279–297. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behary J., Amorim N., Jiang X.T., et al. Gut microbiota impact on the peripheral immune response in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease related hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2021;12:187. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20422-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mager L.F., Burkhard R., Pett N., et al. Microbiome-derived inosine modulates response to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Science. 2020;369:1481–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q., Hu W., Liu W.X., et al. Streptococcus thermophilus inhibits colorectal tumorigenesis through secreting beta-galactosidase. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1179–1193 e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpi R.Z., Barbalho S.M., Sloan K.P., et al. The effects of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in non-alcoholic fat liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:8805. doi: 10.3390/ijms23158805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X., Coker O.O., Chu E.S., et al. Dietary cholesterol drives fatty liver-associated liver cancer by modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Gut. 2021;70:761–774. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng M., Cao H. Fast quantification of short chain fatty acids and ketone bodies by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry after facile derivatization coupled with liquid-liquid extraction. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2018;1083:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albillos A., de Gottardi A., Rescigno M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease: pathophysiological basis for therapy. J Hepatol. 2020;72:558–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vemuri R., Gundamaraju R., Shinde T., et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus DDS-1 modulates intestinal-specific microbiota, short-chain fatty acid and immunological profiles in aging mice. Nutrients. 2019;11:1297. doi: 10.3390/nu11061297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mouries J., Brescia P., Silvestri A., et al. Microbiota-driven gut vascular barrier disruption is a prerequisite for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis development. J Hepatol. 2019;71:1216–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crosas-Molist E., Samain R., Kohlhammer L., et al. Rho GTPase signaling in cancer progression and dissemination. Physiol Rev. 2022;102:455–510. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Secor J.D., Fligor S.C., Tsikis S.T., et al. Free fatty acid receptors as mediators and therapeutic targets in liver disease. Front Physiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.656441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fields T.A., Casey P.J. Signalling functions and biochemical properties of pertussis toxin-resistant G-proteins. Biochem J. 1997;321(Pt 3):561–571. doi: 10.1042/bj3210561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han R., Nusbaum O., Chen X., et al. Valeric acid suppresses liver cancer development by acting as a novel HDAC inhibitor. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;19:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao H., Li X., Chen X., et al. The functional roles of Lactobacillus acidophilus in different physiological and pathological processes. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;32:1226–1233. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2205.05041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong V.W., Won G.L., Chim A.M., et al. Treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with probiotics. A proof-of-concept study. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y., Wang Z., Wan Y., et al. Assessing the in vivo ameliorative effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus KLDS1.0901 for induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease treatment. Front Nutr. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1147423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llovet J.M., Kelley R.K., Villanueva A., et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee N.Y., Shin M.J., Youn G.S., et al. Lactobacillus attenuates progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by lowering cholesterol and steatosis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021;27:110–124. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2020.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorrington M.G., Bradfield C.J., Lack J.B., et al. Type I IFNs facilitate innate immune control of the opportunistic bacteria Burkholderia cenocepacia in the macrophage cytosol. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song Q., Zhang X., Liu W., et al. Bifidobacterium pseudolongum-generated acetate suppresses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2023;79(6):1352–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y., Lau H.C., Yu J. Microbial metabolites in colorectal tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. Gut Microbes. 2023;15 doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2203968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khedr O.M.S., El-Sonbaty S.M., Moawed F.S.M., et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356 exopolysaccharides suppresses mediators of inflammation through the inhibition of TLR2/STAT-3/P38-MAPK pathway in DEN-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats. Nutr Cancer. 2022;74:1037–1047. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2021.1934490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markowiak-Kopec P., Slizewska K. The effect of probiotics on the production of short-chain fatty acids by human intestinal microbiome. Nutrients. 2020;12:1107. doi: 10.3390/nu12041107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canfora E.E., Meex R.C.R., Venema K., et al. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:261–273. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0156-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McBrearty N., Arzumanyan A., Bichenkov E., et al. Short chain fatty acids delay the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in HBx transgenic mice. Neoplasia. 2021;23:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2021.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu C., Xu B., Wang X., et al. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids regulate group 3 innate lymphoid cells in HCC. Hepatology. 2023;77:48–64. doi: 10.1002/hep.32449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Che Y., Chen G., Guo Q., et al. Gut microbial metabolite butyrate improves anticancer therapy by regulating intracellular calcium homeostasis. Hepatology. 2023;78:88–102. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Poul E., Loison C., Struyf S., et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25481–25489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia J.K., Qin X.Q., Zhang L., et al. Roles and regulation of histone acetylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Genet. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.982222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.