Abstract

The outer membrane of Borrelia hermsii has been shown by freeze-fracture analysis to contain a low density of membrane-spanning outer membrane proteins which have not yet been isolated or identified. In this study, we report the purification of outer membrane vesicles (OMV) from B. hermsii HS-1 and the subsequent identification of their constituent outer membrane proteins. The B. hermsii outer membranes were released by vigorous vortexing of whole organisms in low-pH, hypotonic citrate buffer and isolated by isopycnic sucrose gradient centrifugation. The isolated OMV exhibited porin activities ranging from 0.2 to 7.2 nS, consistent with their outer membrane origin. Purified OMV were shown to be relatively free of inner membrane contamination by the absence of measurable β-NADH oxidase activity and the absence of protoplasmic cylinder-associated proteins observed by Coomassie blue staining. Approximately 60 protein spots (some of which are putative isoelectric isomers) with 25 distinct molecular weights were identified as constituents of the OMV enrichment. The majority of these proteins were also shown to be antigenic with sera from B. hermsii-infected mice. Seven of these antigenic proteins were labeled with [3H]palmitate, including the surface-exposed glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase, the variable major proteins 7 and 33, and proteins of 15, 17, 38, 42, and 67 kDa, indicating that they are lipoprotein constituents of the outer membrane. In addition, immunoblot analysis of the OMV probed with antiserum to the Borrelia garinii surface-exposed p66/Oms66 porin protein demonstrated the presence of a p66 (Oms66) outer membrane homolog. Treatment of intact B. hermsii with proteinase K resulted in the partial proteolysis of the Oms66/p66 homolog, indicating that it is surface exposed. This identification and characterization of the OMV proteins should aid in further studies of pathogenesis and immunity of tick-borne relapsing fever.

Human relapsing fever is caused by the transmission of various Borrelia species from either Ornithodoros soft-bodied ticks or the human body louse, Pediculus humanus. Borrelia hermsii, Borrelia parkeri, Borrelia turicatae, and Borrelia duttonii are etiologic agents of tick-borne relapsing fever, while Borrelia recurrentis is one of the etiologic agents of louse-borne relapsing fever (2). Upon infection, the organisms disseminate into the bloodstream and cause recurring episodes of intermittent high fever. This relapse phenomenon has been attributed to the unique ability of these organisms to undergo multiphasic antigenic variation of an abundant surface-exposed lipoprotein designated the variable major protein (Vmp) (5, 41). The molecular basis of Vmp antigenic variation has been well characterized (1, 11, 20, 23, 26–28). Our attention has been focused on identifying and characterizing surface-exposed outer membrane proteins conserved among the different serotypes of B. hermsii.

Relatively little is known about B. hermsii outer membrane proteins or the molecules involved in the pathogenesis of relapsing fever. B. hermsii has an extremely low density of membrane-spanning outer membrane proteins as observed by freeze-fracture electron microscopy, containing approximately 50-fold-fewer membrane-spanning outer membrane proteins than the outer membrane of Escherichia coli (44). Although visualized by freeze-fracture analysis, neither the B. hermsii outer membrane nor its constituent membrane-spanning proteins have been isolated or characterized. Since outer membrane proteins can be surface targets of host immunity and potential virulence factors, the characterization of these rare outer membrane proteins in an organism that undergoes antigenic variation is of particular importance to understanding the pathogenesis of relapsing fever and is potentially relevant to development of an efficacious vaccine.

Recently, the outer membranes of Treponema pallidum, Treponema vincentii, and Borrelia burgdorferi were isolated by a novel method through the use of a low-pH hypotonic citrate buffer (8, 39). In this study, we report the application of this technique to the isolation of the B. hermsii outer membrane, and the constituent outer membrane vesicle (OMV) proteins are described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

B. hermsii HS-1 serotypes 7 and 33 (41, 42) are virulent and avirulent Ornithodoros tick isolates, respectively, and were grown in BSK H medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) supplemented with 6% normal rabbit serum (Sigma) at 34°C (36). All studies reported here were performed with B. hermsii serotype 7 except where noted otherwise.

Isolation of B. hermsii outer membrane.

B. hermsii OMVs were generated by using the methods previously described for the isolation of the B. burgdorferi OMVs (39). Briefly, approximately 500 ml of B. hermsii (1011 organisms) was centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 20 min at room temperature and washed twice with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) (PBS) supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Intergen Co., Purchase, N.Y.). The pelleted cells were resuspended in 90 ml of ice-cold 25 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.2) containing 0.1% BSA. The suspension was vigorously shaken for 2 h at room temperature and vortexed for 1 min every 15 min in order to release OMVs. The suspension was then centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, and the pelleted protoplasmic cylinders and OMVs were resuspended in 12 ml of 25 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.2) with 0.1% BSA. The samples (6 ml) were layered onto discontinuous sucrose gradients consisting of 12.5 ml of 25% (wt/wt) sucrose, 15.5 ml of 42% sucrose, and 5 ml of 56% sucrose and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 16 h at 4°C. The OMV band (upper band) and protoplasmic cylinder band (lower band) were removed by needle aspiration and diluted fivefold with PBS. The protoplasmic cylinders were pelleted at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, resuspended in 1 ml of PBS, and frozen at −80°C. The OMV material was pelleted at 141,000 × g for 4 h, resuspended in 1 ml of 25 mM citrate (pH 3.2), applied to a 10 to 42% (wt/wt) continuous sucrose gradient, and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 16 h at 4°C. The OMV band was needle aspirated as described above, diluted sevenfold with PBS, and pelleted at 141,000 × g at 4°C. The OMV preparation was resuspended in 200 μl of PBS containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and frozen at −80°C.

Intrinsic labeling of B. hermsii with [3H]palmitate.

To identify outer membrane-associated lipoproteins, a 500-ml culture of B. hermsii (1011 organisms) was radiolabeled with 5 mCi of [3H]palmitate (Amersham Corp., Amersham, United Kingdom) for 48 h as described by Skare et al. (39). The radiolabeled cells were then processed as described above to isolate the outer membrane. Isolated OMVs were analyzed by two-dimensional isoelectric focusing followed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as described below. The electrophoresed gel was fixed with 40% isopropanol–10% acetic acid for 30 min, incubated in Amplify fluor (Amersham Corp.) for 30 min, dried under vacuum at 70°C for 1 h, and exposed to X-AR5 film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, N.Y.) for 3 months as previously described (39).

Electron microscopy.

Suspensions of whole organisms, protoplasmic cylinders, and OMVs were placed on carbon-coated 300-mesh copper grids (Ted Pella Inc., Tustin, Calif.) for 5 min, washed in PBS, further washed in distilled H2O, and stained with 1% uranyl acetate as previously described (8, 39). Processed samples were visualized with a JEOL electron microscope with an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

Planar lipid membrane assays.

Isolated outer membrane was solubilized in 2% Triton X-100–PBS (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 30 min. Unsolubilized material was removed by centrifugation at 35,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was diluted 1:1,000 to 1:10,000 in 1 M KCl–10 mM Tris (pH 7.0) and assayed for porin activity in the planar lipid bilayer assay as previously described (39). Lipid bilayers were formed by using a 1.5% (wt/vol) solution of diphytanoyl phosphatidylcholine (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, Ala.) in heptane.

β-NADH oxidase assay.

To assay for β-NADH oxidase activity, B. hermsii protoplasmic cylinders and OMVs were isolated as described above except that 0.5 mM dithiothreitol was added to all buffers and sucrose solutions. Twenty-two successive 1.8-ml fractions were collected from the sucrose gradient, and their refractive indices were determined. The concentration of protein in each sucrose gradient fraction was determined by using the bicinchoninic acid assay system (Pierce Co., Rockford, Ill.). For the β-NADH oxidase assay, 90 μl of each gradient fraction was added to 0.5 ml of 2× assay mix containing 0.4 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 0.3 ml of 0.1% NaHCO3, and 0.1 ml of 0.2-mg/ml β-NADH (22, 39, 40). The changes in absorbance were measured every 5 s for 1 min with a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 340 nm.

Triton X-114 phase separation.

Outer membrane material from 3 × 109 B. hermsii organisms was solubilized with 2% Triton X-114, and the phases were separated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as previously described (12, 39).

One- and two-dimensional SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was performed as previously described (8, 21). OMVs were pelleted at 45,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C and solubilized for 1 h at room temperature in sample buffer consisting of 9 M urea, 2% Nonidet P-40, 1.6% pH 5 to 7 ampholines, and 0.4% pH 3 to 10 ampholines. Isoelectric focusing was carried out for 18 h at a constant voltage of 600 V in polyacrylamide tube gels (8). After electrophoresis in the first dimension, tube gels were incubated for 15 min in 2× SDS-PAGE final sample buffer (17) prior to separation by SDS-PAGE. Electrophoresed proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) membrane (43) and stained with either 1% amido black or Aurodye Forte (Amersham). For immunoblot analysis, endoflagellin monoclonal antibodies (H9724) (4) and monoclonal antibodies to Vmp33 (H4825) (3) (both kindly provided by Alan Barbour, University of California, Irvine) were diluted 1:50 and 1:500 respectively, while anti-p66 (kindly provided by Sven Bergstrom, University of Umea, Umea, Sweden) (10), anti-Gpd (36), and infection-derived mouse serum (36) were diluted 1:1,000 in 5% milk–Tween 20–PBS. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham) against either mouse or rabbit immunoglobulin were used at a dilution of 1:2,500. Antigen-antibody complexes were detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham) and exposed to Kodak X-AR5 film.

Surface proteolysis of B. hermsii.

Proteinase K digestion was performed as described by Barbour et al. (3). Whole intact B. hermsii HS-1 serotype 33 organisms (109) were washed once with PBS–5 mM MgCl2 and resuspended in 150 μl of the same buffer. Fifty microliters of proteinase K (4 mg/ml) or distilled H2O was added, and the cells were incubated at room temperature for 40 min. PMSF (1 mg/ml) was added to stop the reaction. The cells were washed once with PBS–5 mM MgCl2–1 mM PMSF and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described above.

RESULTS

Isolation of the B. hermsii outer membrane.

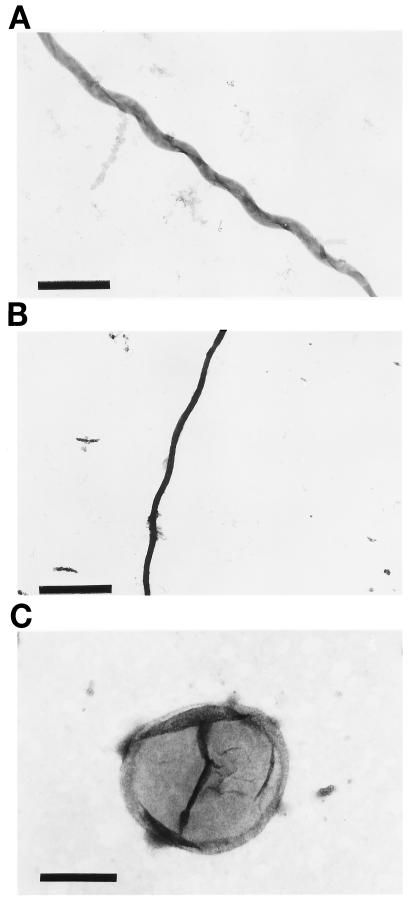

Treatment of B. hermsii with 25 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.2), which dissociates endoflagella into individual endoflagellin subunits (7, 8), resulted in the release of the outer membrane as observed by the decrease in the apparent diameter of the organism (Fig. 1A and B), the absence of endoflagellar filaments (Fig. 1B), and the appearance of released membrane vesicles (Fig. 1C). Isopycnic sucrose gradient centrifugation of the released membrane material resulted in the separation of the outer membrane from protoplasmic cylinders. The OMVs banded in sucrose at a density of 1.15 g/ml (35% [wt/wt] sucrose), while the protoplasmic cylinders banded at a density of 1.22 g/ml (49% [wt/wt] sucrose) (data not shown). Whole-mount electron microscopy of the OMV material with a density of 1.15 g/ml demonstrated membrane vesicles and the absence of contaminating protoplasmic cylinders (Fig. 1C), while dark-field microscopy demonstrated that the material with a density of 1.22 g/ml consisted of protoplasmic cylinders and some OMVs (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Whole-mount electron microscopy of OMVs isolated from B. hermsii. (A) Whole B. hermsii HS-1. Bar, 1 μm. (B) B. hermsii following treatment with 0.25 M citrate buffer, pH 3.2. Bar, 1 μm. (C) Sucrose gradient-purified B. hermsii OMVs. Bar, 0.1 μm.

Detection of OMV porin activity.

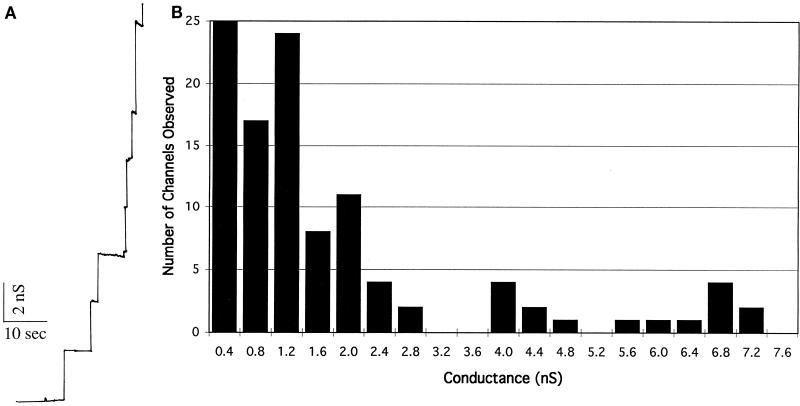

To demonstrate the outer membrane nature of the preparation, purified OMVs were assayed for porin activity. Planar lipid bilayer analysis of Triton X-100-solubilized OMV material resulted in stepwise increases in the conductance across the membrane, indicating the presence of porin proteins in the outer membrane (Fig. 2A). The porin activities from 107 independent insertional events ranged in single-channel conductances from 0.2 to 7.2 nS (Fig. 2B), confirming the outer membrane nature of the preparation.

FIG. 2.

Porin activity of purified B. hermsii OMVs. (A) Single-channel conductance increases of Triton X-100-solubilized B. hermsii outer membrane added to the planar lipid bilayer assay bathed in 1 M KCl–10 mM Tris, pH 7.0. (B) Histogram of the 107 individual single-channel conductance events observed for the Triton X-100-solubilized B. hermsii outer membrane protein.

Purity of the B. hermsii OMV preparation.

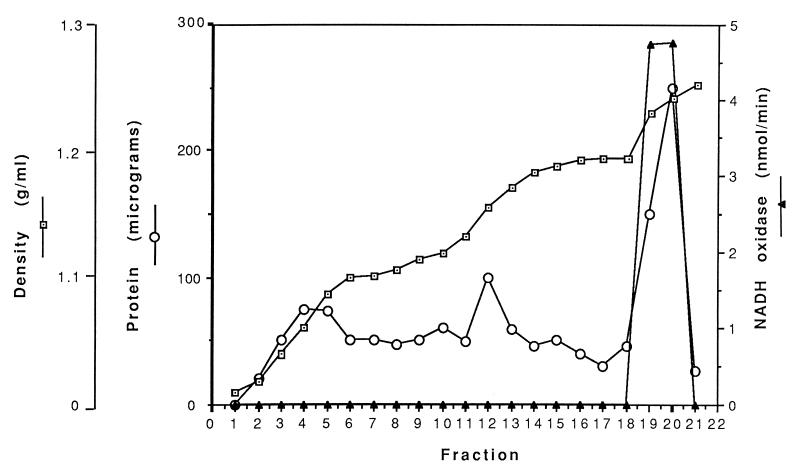

To determine if there was inner membrane and periplasmic contamination, OMV material was analyzed for β-NADH oxidase and endoflagella, respectively. Sequential 1.8-ml aliquots from the sucrose gradient derived from 8.1 × 1010 B. hermsii organisms were analyzed for the inner membrane enzyme β-NADH oxidase, as well as for protein concentration and sucrose density (Fig. 3). Regions of the gradient containing the outer membrane and protoplasmic cylinders corresponded to the protein peaks in fractions 12 and 20, respectively. β-NADH oxidase activity was detected only in fractions 19 to 21, which contained the inner membrane-complexed protoplasmic cylinders (4 × 109 organism equivalents). Further disruption of the protoplasmic cylinders by sonication revealed that the β-NADH oxidase activity observed in the protoplasmic cylinders resided only in the insoluble membrane fraction and was not detectable in the soluble fraction (data not shown). β-NADH oxidase activity was not detected in outer membrane fractions 11 to 13 derived from 4 × 109 organisms or in 10 times more material containing 4 × 1010 organism equivalents. These findings indicate that β-NADH oxidase is associated with the B. hermsii inner membrane and that the isolated OMV preparation was relatively free of measurable inner membrane contamination.

FIG. 3.

Fate of inner membrane-associated β-NADH oxidase during OMV purification. Successive sucrose gradient fractions are indicated on the horizontal axis. Fractions 11 to 13 contain OMV material, and fractions 19 to 21 contain protoplasmic cylinders.

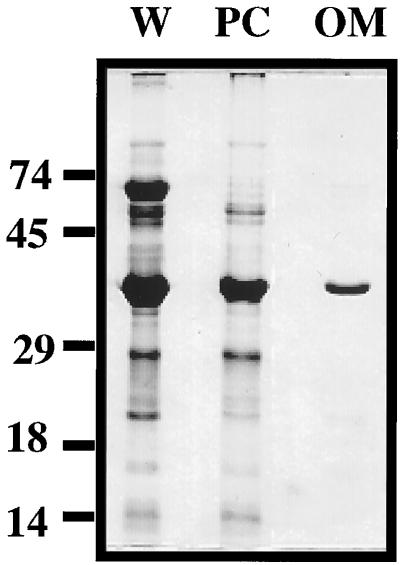

Further comparison of the protein profiles of equivalent amounts of whole organisms, protoplasmic cylinders, and isolated outer membrane visualized by Coomassie blue staining revealed that the isolated outer membrane fraction contained significantly fewer proteins than were found in whole organisms and protoplasmic cylinders (Fig. 4). Besides Vmp, only three other proteins (20, 50, and 60 kDa) were visible in the OMV fraction. In contrast, the majority of the proteins observed in whole organisms were also found in the protoplasmic cylinders, indicating that the majority of the inner membrane proteins remained associated with the protoplasmic cylinders and were not extracted with the outer membrane. These results further support our data that this citrate procedure enriches for outer membrane without significant inner membrane contamination.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the protein compositions of 108 organism equivalents of whole B. hermsii (lane W), protoplasmic cylinders (lane PC), and outer membrane (lane OM). Fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. Numbers on the left are molecular masses in kilodaltons. This figure was generated with a Deskscan II program.

Immunoblot analysis with a monoclonal antibody to the periplasmic endoflagella (H9724) demonstrated that endoflagella were a minor contaminant of the OMV preparation based on the small amount of detectable protein (see Fig. 7C) relative to the large amount of endoflagella in the starting material of whole organisms (data not shown).

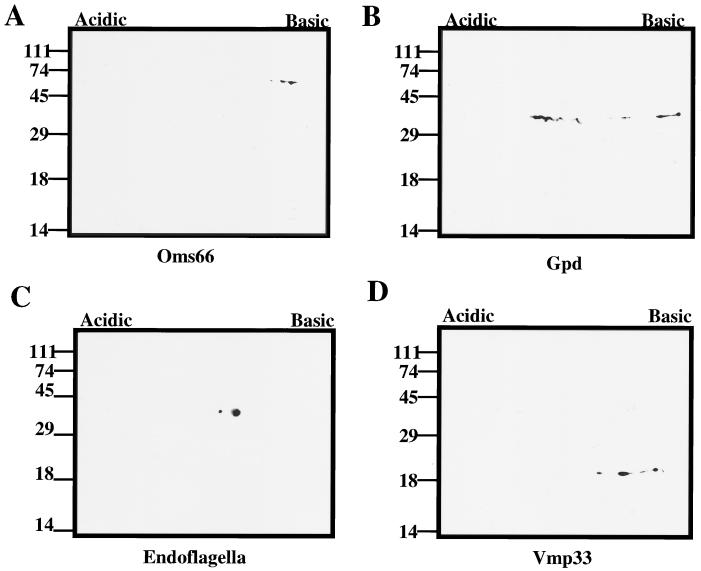

FIG. 7.

Identification of specific outer membrane protein antigens. Western immunoblot analysis of OMVs isolated from 3 × 109 B. hermsii organisms probed with antisera to p66 (A), Gpd (B), endoflagella (H9724) (C), and Vmp33 (H4825) (D) is shown. Sizes of protein molecular mass markers are indicated to the left in kilodaltons. This figure was generated with a Deskscan II program.

Identification of B. hermsii OMV proteins: lipoproteins, outer membrane antigens, and outer membrane-spanning proteins.

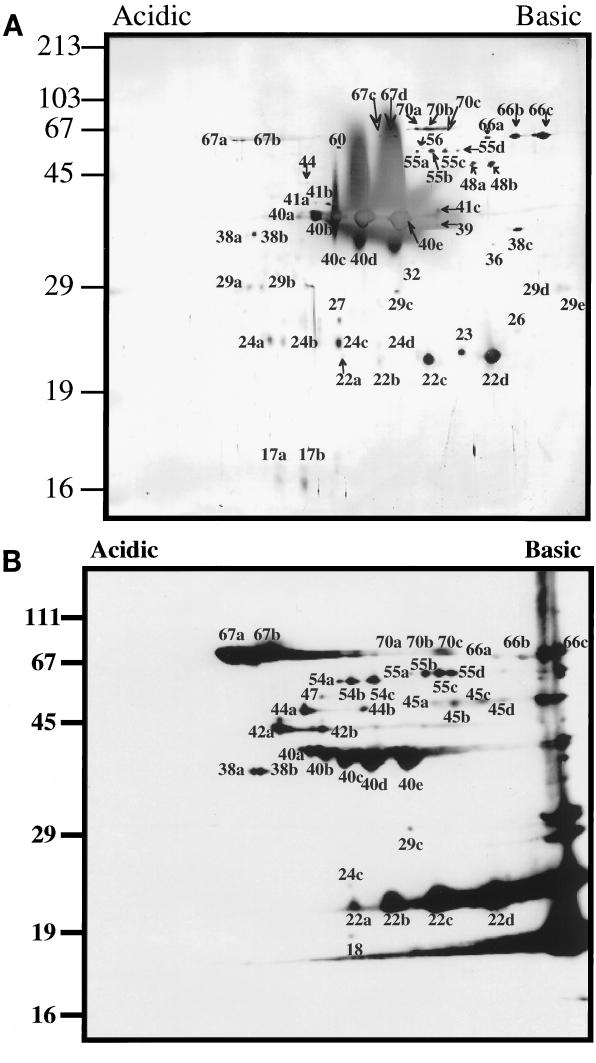

To characterize the protein constituents of the OMVs, samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting; palmitate-labeled samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography. The results are summarized in Table 1. Colloidal gold staining of transferred OMV material derived from 5 × 109 B. hermsii organisms revealed approximately 60 protein spots with 25 distinct molecular masses ranging from 15 to 70 kDa (Fig. 5A). Analysis of the approximately 60 protein spots suggested that some of these spots are putative isoelectric isomers of the same protein. Immunoblot analysis with infection-derived mouse serum demonstrated that the majority of these proteins were also immunogenic (Fig. 5B; Table 1). Six of these antigenic proteins, 18, 42a and b, 44b, 45a to d, 47, and 54a to c, were detected only by immunoblot analysis. Treatment of the outer membrane material with Triton X-114 followed by phase partitioning demonstrated that the majority of the outer membrane proteins, with the exception of flagellin, partitioned into the hydrophobic detergent phase (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Protein composition of B. hermsii OMVs

| Proteina | Descriptionb |

|---|---|

| 15 | L |

| 17a, b | L |

| 18 | A*, Oms |

| 22a | A, L |

| 22b, c, d (Vmp33) | A, L, I |

| 23 | Oms |

| 24a, b | Oms |

| 24c | A, Oms |

| 24d | Oms |

| 26 | Oms |

| 27 | Oms |

| 29a, b | Oms |

| 29c | A, Oms |

| 29d, e | Oms |

| 32 | Oms |

| 36 | Oms |

| 38a, b | A, L |

| 38c | Oms |

| 39 | Oms |

| 40a (Gpd) | A, L |

| 40b, c, d, e | A, L, I |

| 41a, b | Oms |

| 41c | Oms |

| 42a, b | A*, L |

| 44a | A, Oms |

| 44b | A*, Oms |

| 45a, b, c, d | A*, Oms |

| 47 | A*, Oms |

| 48a, b | Oms |

| 54a, b, c | A*, Oms |

| 55a, b, c, d | A, Oms |

| 56 | Oms |

| 60 | Oms |

| 66a, b, c (p66) | A, Oms, I |

| 67a, b | A, L, Oms |

| 67c, d | Oms |

| 70a, b, c | A, Oms |

Letters following numbers represent protein spots of the same molecular weight in the order of most acidic to most basic.

A*, detected only by immunoblotting; A, antigenic; L, lipoprotein; Oms, candidate outer membrane-spanning protein; I, isoelectric isomer.

FIG. 5.

Two-dimensional profile of constituent B. hermsii outer membrane proteins. (A) Colloidal gold stain of OMVs from 109 B. hermsii organisms. (B) Western immunoblot of OMVs from 109 B. hermsii organisms with infection-derived mouse serum. Lowercase letters after the numbers distinguish proteins of identical molecular mass with different pI values. The most acidic spot is designated a, while subsequent letter assignments refer to spots with more basic pI values. Sizes of protein molecular mass markers are indicated to the left in kilodaltons. This figure was generated with a Deskscan II program.

Identification of outer membrane lipoproteins.

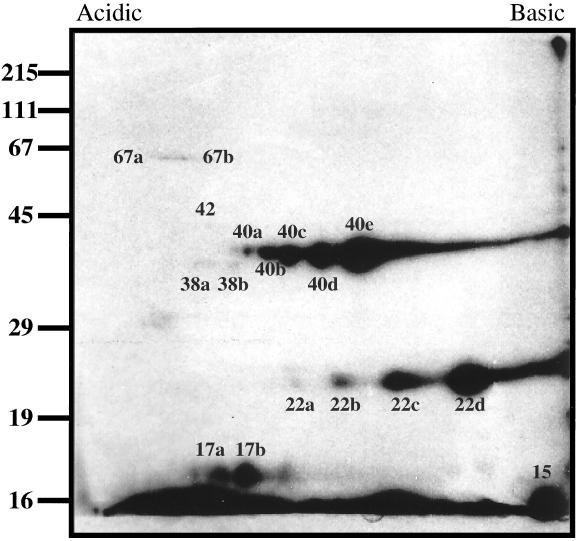

To determine if lipoproteins other than Vmps were present in the OMVs, whole organisms were labeled with tritiated palmitate prior to isolation of the outer membrane. Two-dimensional and SDS-PAGE analysis of 8.5 × 109 organism equivalents of isolated outer membrane identified seven lipoproteins designated 15, 17a and b, 22a to d, 38a and b, 40a to e, 42a and b, and 67a and b (Fig. 6). Given that the 17-kDa lipoprotein was a minor colloidal-gold-stained protein equivalent to other OMV proteins which were not palmitate labeled, it is unlikely that the sensitivity of detection is a factor in detecting lipoproteins.

FIG. 6.

[3H]palmitate-labeled B. hermsii outer membrane lipoproteins. B. hermsii was intrinsically labeled with [3H]palmitate, and the OMVs were isolated and analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis. A fluorogram of 8.5 × 109 organism equivalents of outer membrane is shown. Sizes of protein molecular mass markers are indicated to the left in kilodaltons. This figure was generated with a Deskscan II program.

Antigenic identification of specific proteins associated with the outer membrane.

Immunoblot analysis of OMVs was performed with antisera specific for Vmp33 (3), Borrelia garinii p66/Oms66 surface-exposed porin protein (10, 38), the recently described B. hermsii glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase lipoprotein homolog (32, 36) that we have termed Gpd (36), and endoflagellum (4) (Fig. 7). Immunoblotting with antiserum to Vmp33 indicated that the three palmitate-labeled isoelectric isomers 22b, c, and d identified in Fig. 6 are Vmp33. Based on molecular mass and pI, the four palmitate-labeled isoelectric isomers 40b, c, d, and e are most likely Vmp7 (11). Immunoblot analysis with antiserum to Gpd demonstrated that the minor 40a palmitate-labeled protein is Gpd. Antiserum to the B. garinii surface-exposed p66/Oms66 protein showed the detection of a homolog of identical molecular mass in the B. hermsii OMV preparation (66a, b, and c) (Fig. 7A). As mentioned above, endoflagellum (40 kDa) was found to be a minor contaminant of the OMV preparation (Fig. 7C).

Identification of OMV candidate outer membrane-spanning proteins.

Because some of the proteins identified above were not lipoproteins and phase partitioned into the hydrophobic detergent phase, we have designated the 18, 23, 24a to d, 26, 27, 29a to e, 32, 36, 38c, 39, 41a to c, 44a and b, 45a to d, 47, 48a and b, 54a to c, 55a to d, 56, 60, 66a to c, 67a to c, and 70a to c proteins as candidate outer membrane-spanning proteins (Oms).

Identification of surface-exposed outer membrane proteins.

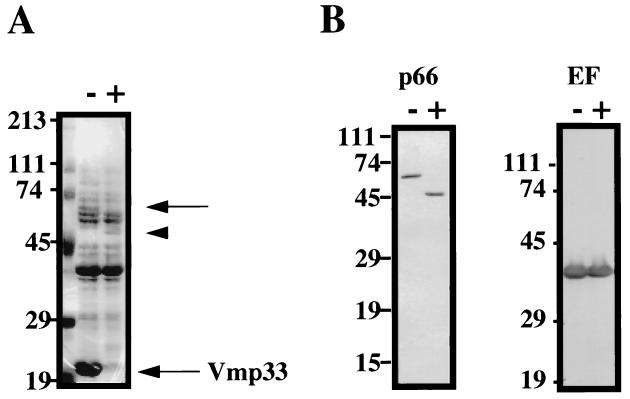

In order to identify OMV-associated proteins with surface exposure on intact organisms, B. hermsii HS-1 serotype 33 was treated with proteinase K prior to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis (Fig. 8). As shown on the Coomassie blue-stained gel following SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 8A), both Vmp33 (22 kDa) and a 66-kDa protein were proteolyzed following proteinase K treatment, while a 50-kDa protein was subsequently detected. In contrast, no effect on the major 41-kDa subsurface endoflagellar protein was observed, indicating the specificity of surface proteolysis in this experiment. These results were further confirmed and extended by immunoblot analysis with specific antisera which showed that the 66-kDa B. hermsii p66/Oms66 homolog was proteolyzed to a 50-kDa form after proteinase K treatment, while the 41-kDa endoflagellar protein was not affected (Fig. 8B). Immunoblot analysis with antiserum to Gpd did not indicate significant proteolysis (data not shown). However, we have recently found that Gpd, but not endoflagella, was surface immunoprecipitated from intact organisms, suggesting that some Gpd is surface exposed (33).

FIG. 8.

Surface proteolysis of B. hermsii HS-1 serotype 33. Whole intact organisms (108) treated (+) or untreated (−) with proteinase K were analyzed by Coomassie blue staining (A) or Western immunoblotting with antisera to endoflagella (EF) and p66 (B). The location of the unproteolyzed endoflagella are indicated by the upper arrow. The location of the 50-kDa proteolyzed p66 is indicated by the arrowhead. The location of Vmp33 is indicated. Sizes of protein molecular mass markers are indicated to the left in kilodaltons. This figure was generated with a Deskscan II program.

DISCUSSION

The B. hermsii outer membrane contains relatively few outer membrane-spanning proteins (44). Although visualized by freeze-fracture electron microscopy, these outer membrane-spanning proteins (designated Oms) have not been isolated or further characterized. In this report we describe the isolation of the outer membrane of B. hermsii and characterization of its constituent proteins.

Treatment of B. hermsii with citrate buffer at pH 3.2, as has been reported for T. pallidum, T. vincentii, and B. burgdorferi (8, 39), resulted in the selective release and subsequent purification of OMVs. As was the finding with T. pallidum and B. burgdorferi, use of this procedure resulted in only an approximately 20 to 50% release of the outer membrane, while part of the outer membrane remained associated with the protoplasmic cylinders (data not shown). The B. hermsii outer membrane banded in a sucrose gradient at a density equivalent to 35% sucrose or 1.15 g/ml, which is similar to the density of the outer membrane material reported for B. burgdorferi (31% sucrose; 1.13 g/ml) (39) while differing significantly from the lower density of the previously reported T. pallidum outer membrane (7% sucrose) (8).

Because there are no B. hermsii outer membrane markers and because porin proteins are indisputable outer membrane-spanning proteins with detectable activity, we analyzed the B. hermsii OMVs for porin activity. Use of a planar lipid bilayer model membrane system indicated the presence of several OMV porin activities with single-channel conductances observed in a wide range from 0.2 to 7.2 nS. The detection of small and large porin channels has been reported for other spirochetes. Small channels of 0.6 nS for the B. burgdorferi Oms28 (37), 1.1 nS for the Leptospira kirschneri OmpL1 (34), and 0.7 nS for the T. pallidum Tromp1 (6, 8) porins have been identified, while larger channels have included the 9.7-nS channel of B. burgdorferi Oms66 (38), the 7.7-nS channel of the 35-kDa protein of Spirochaeta aurantia (16), and the 10.9-nS channel porin of Treponema denticola (13). It is interesting that B. burgdorferi and B. hermsii are the only spirochetes identified to date that possess both large and small porin channel activities, the relevance of which has yet to be determined. Further studies will be required to purify these porin proteins and to characterize their respective activities.

Although some periplasmic endoflagellum was detected in the OMV preparation, it was found to be a minor contaminant based on the small amount detected by immunoblot analysis relative to the large amount of endoflagellum present in whole organisms. The lack of measurable β-NADH oxidase activity indicated that the OMV preparation was relatively free from measurable inner membrane contamination. β-NADH was found only in the inner membrane-enriched protoplasmic cylinders. In order to demonstrate that the lack of detection of β-NADH in the outer membrane was not due to a lack of sensitivity, 10-fold more OMV material was assayed for β-NADH oxidase activity and again was found not to have detectable β-NADH oxidase activity (Fig. 3). The β-NADH assays, showing activity only in the protoplasmic cylinder fraction, show a pattern of activity similar to that for assays performed during the isolation of the B. burgdorferi outer membrane (39). Plaza et al. (24) and Stanton and Jensen (40) have recently reported that β-NADH oxidase is a soluble protein in Serpulina hyodysenteriae. In order to address whether the β-NADH oxidase activity measured in our assays was inner membrane associated or soluble, protoplasmic cylinders were sonicated and the insoluble and soluble fractions were assayed for activity. Preliminary results showed that the majority of the β-NADH oxidase activity remained associated with the insoluble membrane fraction while no activity was observed in the soluble fraction, suggesting that in B. hermsii, β-NADH oxidase is inner membrane associated (data not shown). The observation of membranous material and porin activity along with the lack of β-NADH oxidase activity and the absence of protoplasmic cylinder-associated proteins observed in the OMV fraction all support our conclusion that the citrate protocol results in the release of B. hermsii outer membrane without significant inner membrane contamination.

Western immunoblot analysis with antisera specific to endoflagella, Vmp33, and the surface-exposed B. burgdorferi p66 demonstrated that at least three of the OMV proteins had multiple isoelectric isomers (Fig. 7). Based on similar molecular weights and isoelectric profiles, it is possible that of the approximately 60 protein spots, 17a and b, 24a and b, 29a and b, 29d and e, 38a and b, 41a and b, 42a and b, 45a to d, 48a and b, 54a to c, 55a to d, 67a and b, 67c and d, and 70a to c also are isoelectric isomers of the same proteins and comprise the 25 proteins of distinct molecular weights of the B. hermsii outer membrane (Table 1). Further studies will be required to determine if some of these protein spots are isoelectric isomers of the same proteins. The number of B. hermsii outer membrane proteins is greater than the four proteins identified in the T. pallidum outer membrane (8) but fewer than the 30 proteins identified in the B. burgdorferi outer membrane (39).

Studies with tritiated palmitate demonstrated that 7 of the approximately 25 outer membrane proteins were outer membrane lipoproteins, including five novel species of 15, 17, 38, 42, and 67 kDa as well as the previously described Vmp7, Vmp33, and Gpd proteins (Fig. 6). Sambri et al. have previously reported on nine [3H]palmitate-labeled proteins from whole B. hermsii HS-1 ATCC serotype 33 (30), which included two major surface-exposed proteins with molecular masses of 22 and 24 kDa (31). The 22-kDa protein is most likely Vmp33. Since Sambri et al. performed one-dimensional SDS-PAGE analysis on whole organisms, it is difficult to correlate the other five proteins with the two-dimensional fluorograms of OMVs and protoplasmic cylinders generated in this study. These results are similar to those of our previous studies with B. burgdorferi, in which the outer membrane contained only a few palmitate-labeled lipoproteins (39). Although relatively few palmitate-labeled proteins were identified, we do not believe that sensitivity was a factor in identifying lipoproteins, since the minor 17-kDa protein was palmitate labeled while other proteins of equal intensity were not. However, further studies are required to determine if other outer membrane lipoproteins are not specifically labeled with palmitate. Comparison of [3H]palmitate-labeled proteins associated with the protoplasmic cylinders and those associated with the outer membrane indicates that there is a distinct set of outer membrane lipoproteins (15, 17a and b, Vmp7 and 33, 38a and b, Gpd, 42, and 70b and c) which differs from the larger set of inner membrane-anchored lipoproteins. It is interesting that all spirochetal outer membrane-associated lipoproteins identified to date have also been found to be associated with the inner membrane. These include the 45- and 17-kDa proteins of T. pallidum (8), LipL41 of L. kirschneri (35), and OspA, OspB, and OspD of B. burgdorferi (9, 39). However, not all inner membrane lipoproteins are found to be associated with the outer membrane. The relevance of this distinction to spirochetal physiology and pathogenesis is yet to be determined.

In addition to the identification of outer membrane lipoproteins, we sought to identify candidate outer membrane-spanning proteins, which would be expected to be hydrophobic in nature. With the exception of the periplasmic endoflagella, the majority of the OMV proteins were in fact shown to be hydrophobic, based upon their partitioning into the Triton X-114 detergent phase (data not shown). Based on the identification of the lipoproteins and the periplasmic endoflagella and on the partitioning of the majority of the remaining proteins into the Triton X-114 hydrophobic detergent phase, we have designated these OMV proteins as candidate outer membrane-spanning proteins (Table 1).

The B. burgdorferi surface-exposed 66-kDa protein (p66) was recently shown to also function as a porin protein and is responsible for the single-channel conductance of 9.7 nS (39). Immunoblot analysis of the B. hermsii OMVs with antiserum to B. garinii p66 demonstrated the presence of a putative p66 homolog (Fig. 7), consistent with previous observations (10, 25). Therefore, it is possible that this B. hermsii 66-kDa protein could be responsible for the larger channel of approximately 7 nS observed in the B. hermsii OMV preparation. Our findings that a B. burgdorferi p66/Oms66 porin homolog was also present in B. hermsii is not surprising based on the high genetic homology (88%) between these two species. Rosa et al. (29) have previously demonstrated that the carboxy-terminal end of a PCR target of a chromosomally encoded gene (later shown to be homologous to B. burgdorferi p66) (10) was only 70% identical between B. hermsii and B. burgdorferi. We are currently in the process of cloning the gene encoding the B. hermsii Oms66 homolog.

Our surface proteolysis experiments with B. hermsii have indicated that the Oms66/p66 homolog, like B. burgdorferi p66, is indeed surface exposed (Fig. 8). Proteinase K treatment resulted in a partially proteolyzed 50-kDa form of the p66 homolog, differing from the complete proteolysis of the Vmp33 lipoprotein. These results suggest that a portion of the p66 homolog is not surface exposed and is protected from proteolysis, which is consistent with the protease-resistant properties of other outer membrane-spanning porin proteins.

We and Schwan et al. have recently reported the cloning of the gene encoding a glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase homolog which has been designated Gpd (36) or GlpQ (32). Our finding that Gpd is an outer membrane constituent differs from the location of the E. coli homolog, which is found exclusively in the periplasm (18, 19), but is similar to that of the Haemophilus influenzae Hpd protein, which was found to be a surface exposed lipoprotein (14) and a known virulence factor (15). Although proteinase K treatment of whole B. hermsii did not result in detectable proteolysis of Gpd, surface immunoprecipitation studies of intact B. hermsii did demonstrate at least partial surface exposure of Gpd (data not shown). These results suggest that the majority of Gpd is subsurface and that only a small amount of Gpd is surface exposed. Based on our findings that Gpd is also a surface-exposed outer membrane lipoprotein, it is possible that like Hpd, Gpd may be a virulence factor.

The isolation of the B. hermsii outer membrane has provided us with the opportunity to study potential virulence factors that may contribute to the pathogenesis of relapsing fever. Future studies include identification and characterization of other membrane-spanning outer membrane proteins, determination of their structure-function relationships, and assessment of their potential role(s) as protective immunogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yi-Ping Wang and Xiao-Yang Wu for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI-21352 and AI-29733 (both to M.A.L.), Public Health Service grant AI-37312 (to J.N.M.), National Institutes of Health training grant 2-T32-AI-07323 (to E.S.S.), National Research Service Award AI-09117 (to J.T.S.), and Public Health Service grant MH-01174 (to B.L.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbour A G, Barrera O, Judd R. Structural analysis of the variable major proteins of Borrelia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1983;158:2127–2140. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour A G, Hayes S F. Biology of Borrelia species. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:381–400. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.381-400.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour A G, Tessier S L, Hayes S R. Variation in a major surface protein of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 1984;45:94–100. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.94-100.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbour A G, Hayes S F, Heiland R A, Schrumpf M E, Tessier S L. A Borrelia-specific monoclonal antibody binds to a flagellar epitope. Infect Immun. 1986;52:549–554. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.549-554.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour A G, Tessier S L, Stoenner H G. Variable major proteins of Borrelia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1312–1324. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco D R, Champion C I, Exner M M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Hancock R E W, Tempst P, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Porin activity and sequence analysis of a 31-kilodalton Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum rare outer membrane protein (Tromp1) J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3356–3562. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3556-3562.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco D R, Champion C I, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Antigenic and structural characterization of Treponema pallidum (Nichols strain) endoflagella. Infect Immun. 1988;58:168–175. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.168-175.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanco D R, Reimann K, Skare J, Champion C I, Foley D, Exner M M, Hancock R E W, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Isolation of the outer membranes from Treponema pallidum and Treponema vincentii. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6088–6099. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6088-6099.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brusca J S, McDowall A W, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Localization of outer surface protein A and B in both the outer membrane and intracellular compartments of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:8004–8008. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.8004-8008.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bunikis J, Noppa L, Bergstrom S. Molecular analysis of a 66-kDa protein associated with the outer membrane of Lyme disease Borrelia. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burman N, Bergstrom S, Restrepo B I, Barbour A G. The variable antigens Vmp7 and Vmp21 of the relapsing fever bacterium Borrelia hermsii are structurally analogous to the VSG proteins of the African trypanosome. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1715–1726. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham T M, Walker E M, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Selective release of the Treponema pallidum outer membrane and associated polypeptides with Triton X-114. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5789–5796. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5789-5796.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egli C, Leung W K, Muller K H, Hancock R E W, McBride B C. Pore-forming properties of the major 53-kilodalton surface antigen from the outer sheath of Treponema denticola. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1694–1699. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1694-1699.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janson H, Heden L, Forsgren A. Protein D, the immunoglobulin D-binding protein of Haemophilus influenzae, is a lipoprotein. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1336–1342. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1336-1342.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janson H, Melhus A, Hermansson A, Forsgren A. Protein D, the glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase from Haemophilus influenzae with affinity for human immunoglobulin D, influences virulence in a rat otitis model. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4848–4854. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4848-4854.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kropinski A M, Parr T, Angus B, Hancock R, Ghiorse W, Greenberg E. Isolation of the outer membrane and characterization of the major outer membrane protein from Spirochaeta aurantia. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:172–179. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.172-179.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larson T J, Ehrmann M, Boos W. Periplasmic glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase of Escherichia coli, a new enzyme of the glp regulon. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:5428–5432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larson T J, vanLoo-Bhattacharya A T. Purification and characterization of glpQ-encoded glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase from Escherichia coli K-12. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;260:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meier J T, Simon M I, Barbour A G. Antigenic variation is associated with DNA rearrangements in a relapsing fever Borrelia. Cell. 1985;41:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Farrell P Z, Goodman H M, O’Farrell P H. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of basic as well as acidic proteins. Cell. 1977;2:1133–1142. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osborn M J, Gander J E, Parisi E, Carson J. Mechanism of assembly of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium: isolation and characterization of cytoplasmic and outer membrane. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:3962–3972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plasterk R H A, Somon M I, Barbour A G. Transposition of structural genes to an expression sequence on a linear plasmid causes antigenic variation in the bacterium Borrelia hermsii. Nature (London) 1985;318:257–263. doi: 10.1038/318257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plaza H, Whelchel T R, Garczynski S F, Howerth E W, Gherardini F C. Purified outer membranes of Serpulina hyodysenteriae contain cholesterol. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5414–5421. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5414-5421.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Probert W S, Allsup K M, LeFebvre R B. Identification and characterization of a surface-exposed, 66-kilodalton protein from Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1933–1939. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1933-1939.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Restrepo B I, Barbour A G. Antigen diversity in the bacterium B. hermsii through “somatic” mutations in rearranged vmp genes. Cell. 1994;78:867–876. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Restrepo B I, Carter C J, Barbour A G. Activation of a vmp pseudogene in Borrelia hermsii: an alternate mechanism of antigenic variation during relapsing fever. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:287–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Restrepo B I, Kitten T, Carter C J, Infante D, Barbour A G. Subtelemeric expression regions of Borrelia hermsii linear plasmids are highly polymorphic. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3299–3311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosa P A, Hogan D, Schwan T G. Polymerase chain reaction analysis identify two distinct classes of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:524–532. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.524-532.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambri V, Cevenini R. Incorporation of cysteine by Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia hermsii. Can J Microbiol. 1991;38:1016–1021. doi: 10.1139/m92-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambri V, Marangoni A, Massaria F, Farencena A, La Placa M, Cevenini R. Functional activities of antibodies directed against surface lipoproteins of Borrelia hermsii. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:623–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwan T G, Schrumpf M E, Hinnenbusch B J, Anderson D E, Konkel M E. GlpQ: an antigen for serological discrimination between relapsing fever and lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2483–2492. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2483-2492.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shang, E. S., and M. A. Lovett. Unpublished observations.

- 34.Shang E S, Exner M M, Summers T A, Martinich C, Champion C I, Hancock R E W, Haake D A. The rare outer membrane protein, OmpL1, of pathogenic Leptospira species is a heat-modifiable porin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3174–3181. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3174-3181.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shang E S, Summers T A, Haake D A. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding LipL41, a surface-exposed lipoprotein of pathogenic Leptospira species. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2322–2330. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2322-2330.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shang E S, Skare J T, Exner M M, Blanco D R, Kagan B L, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Isolation and characterization of a 40-kilodalton Borrelia hermsii glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase homolog. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2238–2246. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2238-2246.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skare J T, Champion C I, Mirzabekov T A, Shang E S, Blanco D R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Kagan B L, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Porin activity of the native and recombinant outer membrane protein Oms28 of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4909–4918. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4909-4918.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skare J T, Mirzabekov T A, Shang E S, Erdjument-Bromage H, Blanco D R, Tempst P, Kagan B L, Miller J N, Lovett M A. The Oms66 (p66) protein is a Borrelia burgdorferi porin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3654–3661. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3654-3661.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skare J T, Shang E S, Foley D M, Blanco D R, Champion C I, Mirzabekov T, Sokolov Y, Kagan B L, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Virulent strain-associated outer membrane proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2380–2392. doi: 10.1172/JCI118295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanton T B, Jensen N S. Purification and characterization of NADH oxidase from Serpulina (Treponema) hyodysenteriae. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2980–2987. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2980-2987.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoenner H G, Dodd T, Larsen C. Antigenic variation of Borrelia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1297–1311. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson R S, Burgdorfer W, Russel R, Francis B J. Outbreak of tick-borne relapsing fever in Spokane County Washington. JAMA. 1969;210:1045–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker E M, Bornstein L A, Blanco D R, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Analysis of outer membrane ultrastructure of pathogenic Treponema and Borrelia species by freeze-fracture electron microscopy. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5585–5588. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5585-5588.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]