Abstract

Study Design

Modified DELPHI Consensus Process

Objective

To agree a single unifying term and definition. Globally, cervical myelopathy caused by degenerative changes to the spine is known by over 11 different names. This inconsistency contributes to many clinical and research challenges, including a lack of awareness.

Method

AO Spine RECODE-DCM (Research objectives and Common Data Elements Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy). To determine the index term, a longlist of candidate terms and their rationale, was created using a literature review and interviews. This was shared with the community, to select their preferred terms (248 members (58%) including 149 (60%) surgeons, 45 (18%) other healthcare professionals and 54 (22%) People with DCM or their supporters) and finalized using a consensus meeting. To determine a definition, a medical definition framework was created using inductive thematic analysis of selected International Classification of Disease definitions. Separately, stakeholders submitted their suggested definition which also underwent inductive thematic analysis (317 members (76%), 190 (59%) surgeons, 62 (20%) other healthcare professionals and 72 (23%) persons living with DCM or their supporters). Using this definition framework, a working definition was created based on submitted content, and finalized using consensus meetings.

Results

Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy was selected as the unifying term, defined in short, as a progressive spinal cord injury caused by narrowing of the cervical spinal canal

Conclusion

A consistent term and definition can support education and research initiatives. This was selected using a structured and iterative methodology, which may serve as an exemplar for others in the future.

Keywords: Cervical, Myelopathy, Spondylosis, Spondylotic, Stenosis, Disc Herniation, Ossification Posterior Longitudinal Ligament, degeneration, index term, consensus, health informatics

Introduction

Imagine trying to diagnose, treat, research, or educate in a disease without a common name. Degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM), is a progressive spinal cord injury 1 estimated to affect 1 in 50 adults; 2 it is a heterogeneous condition known by at least 11 different names. 3 DCM is the most common form of cervical myelopathy 4 triggered by degenerative and/or congenital changes to the structure of the cervical spine that exert mechanical stress on the spinal cord and result in a progressive spinal cord injury. 5

The condition was first recognized in 1839 by C Aston-Key, 6 encompasses multiple spinal pathologies, and is referred to as: cervical spondylotic myelopathy, cervical stenosis, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, non-traumatic spinal cord injury and cervical degenerative myelopathy and other conditions. These terms lack definitions and are variable used.7,8

This, and low awareness or comprehension of the disorder, 9 even amongst health professionals, 10 contributes to the challenges DCM patients face: DCM is often undiagnosed, or diagnosed late, which can result in delay of care, often by years.1,2,11,12 As DCM is often progressive, treatment must be optimally timed to offer maximal patient benefit.11,13 These delays therefore translate into greater disability, dependency, and some of the poorest quality of life scores of any chronic disease.11–14

The approach to naming and defining disease is much debated, including what even constitutes a disease.15–19 However, no standardized framework has emerged. Diseases can be known by descriptive terms or proper nouns, including eponymous names. 20 Definitions too are variable, ranging from a description of common symptom patterns to those incorporating the findings of diagnostic tests and/or aetiology. 21

The approach to defining disease has often been classed as either essentialist or nominalist. 22 The former indicates a true certainty to a disease (X is….), whereas the latter reflects a description that remains open to interpretation.15,23 In reality these represent 2 opposite ends of a spectrum. JG Scadding, from whom many of these perspectives arose, favored a more nominalist approach, acknowledging its flexibility to handle uncertainty or as yet unknown facts. The definition of the disease in this context is distinct from its diagnostic criteria,16,18 and traditionally focusses on anatomical and physiological features. 16 Disease nomenclature was historically driven by professionals; however, more recently lasting terminology has been closely influenced by the perspective of patients and families. 20

This article outlines a multistakeholder consensus process to agree a single name and definition for cervical myelopathy caused by degenerative spinal column pathology (AO Spine RECODE DCM). 24

Method

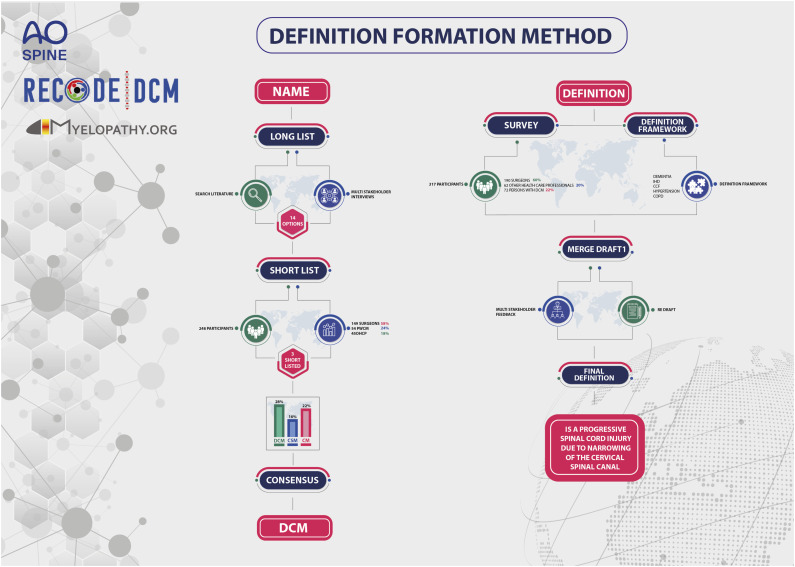

This individual project is part of a wider initiative called the AO Spine RECODE-DCM (aospine.org/recode), for which the protocol has been published. 24 This defined 3 key stakeholder groups: spinal surgeons, other healthcare professionals (oHCP), and DCM patients or carers (PwCM). 25 The project was overseen by an international steering committee (Supplementary Data 1), but day-to-day by a management group. Ethical approval was granted by University of Cambridge. The process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of process to agree a single index term and definition.

Index Term

A list of candidate terms was taken from the literature using a scoping review of 2 clinical trial registers (Clinicaltrials.gov and EU Trials) and MEDLINE (Supplementary Data 2). An inclusive search was built around the terms ‘Cervical’ and ‘Myelopathy’ based on prior validated filters.26,27 The search was performed from database inception to 1st December 2019. MEDLINE articles were searched for systematic reviews or meta-analysis, clinical trial protocols or clinical practice reviews. These latter sources were selected on the basis that preferred disease terms would most likely have been named and defined. In total, 11 different terms were used in the clinical trials registry and 7 different terms in the published literature. These were supplemented during discussion at a steering committee meeting into a longlist of 14 different and unique terms.

A mixed methods approach was taken to establish potential drivers of individual preference. Quantitative analysis of the scoping review identified ‘cervical spondylotic myelopathy’ (‘CSM’) as the most common term used (51%), with ‘degenerative cervical myelopathy’ (‘DCM’) the second most common (19%). The use of ‘DCM’ was only found in the published literature after its proposal by Nouri et al (2015), 8 increasing from 0% to 27%. However, this was predominantly within neurosurgical publications (95%) and by authors with affiliations to those individuals on the original manuscript (70%).

Perspectives from stakeholder groups were captured using a series of interviews, conducted via convenience sampling. Specifically, 2 surgeons and 2 extended scope physiotherapists using 1:1 interviews, a focus group of 8 PwCM (6 female, with on average 6 years of experience living with DCM), and a quorate AO Spine RECODE DCM steering committee meeting. Concepts were inductively analyzed. From these discussions, and mirroring the quantitative analysis, it emerged that 3 terms were most popular: cervical spondylotic myelopathy, degenerative cervical myelopathy and cervical myelopathy. The arguments for and against these terms are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Three most popular candidate terms, with the salient arguments for and against their adoption as the single index term

| Term | Argument For | Argument Against |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical myelopathy | • Fewer syllables | • Not specific (for example, cervical myelopathy would also cover inflammatory, neoplastic and ischaemic pathologies) |

| • Popular amongst non-specialist healthcare professionals | ||

| Cervical spondylotic myelopathy | • Describes the condition | • Many syllables |

| • Hard to pronounce | ||

| • Could be abbreviated | • Ancient Greek, not familiar | |

| • Is OPLL, CSM? | ||

| Degenerative cervical myelopathy | • Umbrella term (subclassification possible, eg CSM and OPLL) | • Many syllables ‘Degenerative’ – potential negative implications |

| • Specific / unique | ||

| • Describes the condition | ||

| • Could be abbreviated | ||

| • Increasingly adopted (eg AO Spine RECODE-DCM) |

These findings were used to form a series of infographics (Supplementary Data 3), incorporated into a survey (SurveyMonkey, California USA) and distributed to the AO Spine RECODE-DCM community (see below). Following review of the infographics, participants were asked to select their preferred term. The sequence in which participants viewed the infographics was randomly allocated to minimize bias. Participants were given the option to justify their selection using a comment box, but also a list of predefined reasons identified during interviews. Results were descriptively analyzed. Free text responses underwent inductive analysis. Findings of the survey were then reviewed at a quorate AO Spine RECODE-DCM steering committee meeting, for a final consensus decision, chaired by an independent facilitator.

The AO Spine RECODE-DCM community is an international network of professionals and people with lived experience. It was originally formed at the start of AO Spine RECODE-DCM, to conduct a James Lind Alliance research priority setting partnership and form a minimum data set for research. The detailed recruitment process and sampling demographics are described separately.

Definition

A medical definition framework was formed by inductive analysis of existing definitions held within the International Classification of Disease (ICD) register. The ICD register was chosen as a reference framework, on the basis that it is an international standard employed around the world and an intended target for dissemination.28,29 A choice of 10 general and well-known conditions were selected by the management group, specifically: congestive heart failure, cerebral ischemic stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic insomina, diabetes, dementia, cirrhosis, pneumonia, hypertension and osteoarthritis. In addition, 5 conditions, within the ICD register, more closely related to myelopathy (multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, hereditary spastic paraplegia, syringomyelia and transverse myelitis) and spondylosis (spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis, intervertebral disc degeneration of the cervical spine without prolapsed disc, inflammatory spondyloarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis) were also selected.

Their respective definitions were extracted from ICD, version 11 and underwent inductive analysis by an individual with no prior knowledge, or experience of DCM or AO Spine RECODE-DCM (KB). This was felt important to avoid the introduction of any pre-conceptions. The principal objective was to identify a framework for a definition’s structure. Differences and technical nuances between types of definition were also compared.

As part of the second-round survey of the AO Spine RECODE-DCM Priority Setting Partnership, participants were asked to select their top research priorities (termed ‘interim prioritisation’), as well as to submit their definition of DCM. The survey was hosted on SurveyMonkey (California, USA) and was disseminated to participants of the first-round survey, but also via a single open call through AO Spine and Myelopathy.org.

Data was imported into NVivo software (version 10, 2012; QSR International Pty Ltd, Victoria, Australia) and underwent pre-processing. Specifically, spelling mistakes corrected, duplicate words combined (eg bodily and body) and conjunctions or prepositions removed. The principal focus was nouns, as these would provide the descriptive content for the definition. Adverbs and adjectives underwent context analysis and were included with their partner noun if they were considered of relevance to interpreting it (eg ‘decreased function’ or ‘significant compression’). These processed words then underwent inductive analysis, to identify a framework of categories that effectively sorted all submitted words. This was completed by 2 reviewers (BMD, and DZK) independently, with any disagreement settled through mutual discussion. Reviewers were not aware at the time of the definition framework based on ICD definitions.

The identified frameworks were then merged (ICD framework, and DCM framework), and using the content from submitted descriptions, a working definition formed by the AO Spine RECODE-DCM management group. The definition was then presented for discussion and feedback at a quorate AO Spine RECODE-DCM steering committee meeting, chaired by an independent facilitator. A process of iteration and re-review continued, until a quorate consensus had been reached.

Results

Index Term

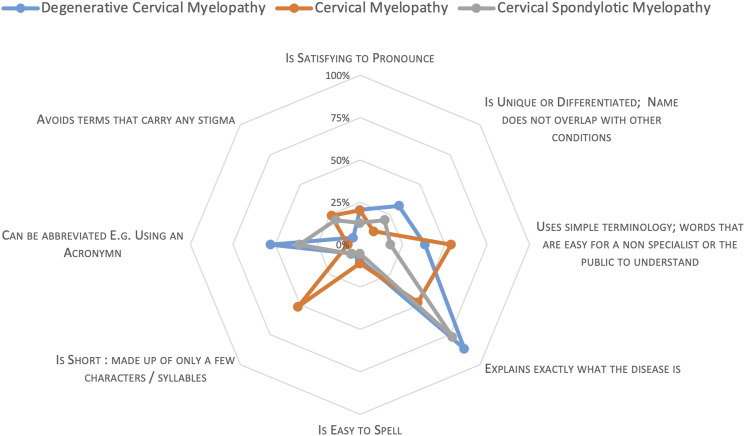

Of the 417 registered email addresses, 248 individuals responded (58% participation) including 54 (22%) PwCM , 149 (60%) surgeons, and 45 (18%) oHCP, with worldwide representation (Supplementary Data 4). With the exception of ‘Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament’ (OPLL), all terms received at least 1 vote. CSM, DCM and cervical myelopathy were the 3 most popular terms, across key stakeholder groups (Supplementary Data 5). Thematic analysis of free text comments left by 41 respondents (19 [46%] Surgeons, 13 [32%] PwCM or their supporters and 9 [22%] oHCP) identified 4 prevailing themes, categorised as “Momentum” (for DCM) (3 [7%]), “Against Degenerative” (3 [7%]), in favour of “Simple Language” (4 [10%]) and in favour of a “Specific Term” (7 [17%]) (Figure 2, Supplementary Data 6). On 2nd November 2020, a virtual consensus meeting was convened to agree the index term. The meeting was attended by 17 representatives (7 Surgeons, 4 oHCP and 6 PwCM) and chaired by an independent facilitator. The pre-meeting process and findings were presented. Comments were invited, which were unanimously in favor of the most popular term ‘DCM’, for reasons of momentum, specificity, simple terminology, and an easier-to-say acronym. The term was selected by poll, with 100% support.

Figure 2.

Radar plot, outlining the common arguments and their relative frequency amongst the 3 shortlisted index terms.

Thematic Analysis of Existing Disease Definitions

A working framework of 4 themes was identified across general medical definitions (Supplementary Data 7), defined as the descriptor, primary, secondary, and tertiary domains (Table 2). Definitions typically contained a primary and secondary domain, covering the pathology and the symptoms separately, and in either order. These domains were sometimes prefaced by a descriptive introduction (‘descriptor domain’) and always companied by a range of further details (‘tertiary domain’). This might include the cause (7 conditions), specific diagnostic criteria (6 conditions), specific exclusions (2 conditions), specification of sub-groups (3 conditions), disease complications (2 conditions), epidemiology (1 condition) or genetic information (2 conditions). For myelopathy and spondylosis related definitions, the pathology of the disease was consistently the primary domain.

Table 2.

Definition framework developed from thematic analysis

| Definition Framework | Present | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Domain | Optional | If this is included, it is always first. Describes disorder. Example phrases, ‘group of… diseases/disorders’, ‘syndrome’, ‘disorder’, ‘disease’, ‘dysfunction’. Generally, these could be interchangeable, but there is space for discussion on whether certain phrases/words matter |

| Primary Domain | Always | Each definition has a primary domain that is used to define the disease. This may be via the underlying pathology or the presenting symptoms. |

| Secondary Domain | Often | Commonly but not always present, this is often a secondary means of defining the disease, 1 that seems to not be sufficient for definition alone; only paired with the primary domain. This pairing is done with phrases such as ‘characterised by’, ‘associated with’, or ‘accompanied by’. This is usually the domain that was not used as a primary domain, and so many definitions utilised both pathology and symptoms. Rarely, both domains are of the same type. |

| Tertiary Domain(s) | Always | ‘Everything else’. An array of types of further detail that may be included to add further specificity. This does not seem to be required or necessary for the definition and can vary in the type of additional information given. If present, this may commonly be the diagnostic criteria that are used for the disease, its prevalence, specific exclusions, or explanations of the cause of the disease. Less commonly, this may be information about a categorisation system for the disease, or potential complications that may arise. |

Selecting a Definition for Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy

Of the 417 participants who performed interim prioritisation, 317 (76%) completed the definition question, specifically 190/214 (89%) Surgeons, 62/96 (65%) oHCP and 72/107 (67%) persons living with DCM or their supporters.

Across groups, ‘spinal’, ‘cord’ and ‘compression’ were consistently prevalent terms, and to a lesser extent ‘degenerative’. Other common descriptors included reference to examination findings (eg ‘signs’, ‘findings’, ‘motor’, ‘sensory’) and investigations (eg ‘imaging’, ‘MRI’ or ‘electrophysiology’). The choice of words, and their popularity, appeared consistent between stakeholder groups.

Content was grouped independently by 2 reviewers, into themes with or without sub-themes. The process was iterative, with informal discussion used to resolve inconsistencies and develop a framework that was able to categorise content across descriptions that is shown in Supplementary Data 8. Specifically, themes of pathology, impact, population, diagnosis and treatment were identified. When subsequently comparing this to the framework identified from general condition definitions, the DCM framework was well aligned: primary (pathology), secondary (impact) and tertiary domains (population, diagnosis and treatment).

Using this and informed by the DCM content that had populated each theme, a draft definition was prepared (Supplementary Data 9). This was first reviewed at a virtual consensus meeting (2nd November 2020). The initial working draft was then exchanged via email, for peer-review and comment. The final revised definition was agreed at a steering committee meeting on 4th June 2021 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Final agreed definition of DCM

| Descriptor | DCM is a progressive spinal cord injury due to narrowing of the cervical spinal canal. |

|---|---|

| Primary Domain | Spinal canal narrowing arises due to osteoarthritic changes to the bone, ligament or disc of the cervical spine (such as disc prolapse or herniation, ligament hypertrophy or ossification, and osteophyte formation), also termed cervical spondylosis. It can also be exacerbated by a pre-existing (ie congenital) stenosis. The narrowing results in repetitive and/or persistent spinal cord compression and spinal cord injury, believed to arise from a combination of ischemia, cell death and inflammatory mediated damage triggered by the mechanical stress. |

| Secondary Domain | A range of symptoms can arise including pain, motor, sensory or autonomic deficits to the neck, hands, limbs or torso as well as bladder and bowel function. The resulting disability varies greatly from individual to individual but is often associated with decreasing quality of life. |

| Tertiary Domains | This disorder most commonly affects adults in mid to later life (>40yrs) and |

| is diagnosed using a combination of clinical signs, symptoms and image findings, although other diagnostic tools, such as electrophysiology are sometimes used to confirm signs of myelopathy or reveal subclinical conditions of cord damage and consider differential diagnoses. | |

| Surgical decompression or close observation is the mainstay of treatment, with a variety of techniques in use. | |

| Without an index term and definition prior to 2020 (established by AO Spine RECODE-DCM), a number of alternative terms have been used, including cervical spondylotic myelopathy, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, cervical stenosis and cervical myelopathy. | |

| For clarity, DCM encompasses: | |

| • Cervical spondylotic myelopathy | |

| And the following, when causing myelopathy (spinal cord disease) in the cervical spine: | |

| • Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) | |

| • Ossification of the ligamentum flavum (OFL) | |

| • Klippel-Feil syndrome | |

| • Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) | |

| • Degenerative disc disease | |

| • Cervical stenosis |

Discussion

AO Spine RECODE DCM has used a modified DELPHI process, informed by the literature and broad international and multistakeholder perspectives, to agree a single index term and produce its first consensus definition. This appears consistent with definitions used for existing conditions and based on the process, suitable for inclusion within ICD. 30

Whilst there were significant strengths to the process, including its global 31 multistakeholder perspective and iterative approach, an important limitation to acknowledge is that the term ‘DCM’ was used from the outset, for example within the supporting and explanatory information, as well as the project title AO Spine RECODE-DCM, as having a term to identify the condition was unavoidable. The inclusion of contrasting terms, alongside their prominence within voting and discussion, is a reassuring suggestion at least, that this did not confer an unconscious bias.

The term DCM was introduced by Nouri et al (2015). 8 The authors had deliberately proposed a new term to reconcile a history of confusion for the disease.32,33 Although first described in 1839, 6 the distinction of DCM from related neurological disease was difficult until its aetiology had been better defined. DCM was initially proposed to be the result of chondromas, 34 however these were subsequently recognized instead as intervertebral disc prolapses 35 The spectrum of related pathology that could cause spinal canal narrowing and injury was extended, and collectively termed ‘spondylosis’; the condition often called ‘cervical spondylosis with myelopathy’, which later became ‘cervical spondylotic myelopathy’. 36 However the term ‘spondylosis’ remained poorly defined and variably interpreted 7 . OPLL for example was considered by some as a distinct entity and others just 1 of the spectrum of pathologies that can cause cervical spondylotic myelopathy. 7 Both views have their basis. For example OPLL has been observed more frequently amongst Asian populations, with several candidate gene mutations linked to its development.37,38 However OPLL frequently co-exists with other degenerate pathology, 39 the clinical phenotype and operative goals are also the same. 5 Moreover its prevalence amongst non-asian populations may-be underrecognized. 40 As Nouri et al (2015) first proposed, this is therefore more likely an important subtype of a common disease. 8 The European League against Rheumatism in 1995 recommended moving away from ‘spondylosis’ in any context due to this collective ambiguity. 41 For DCM, where congenital pathology, such as congenital cervical stenosis or Klippel Fleil syndrome can also contribute, 42 this problem is likely amplified.8,39

Whilst resolving this ambiguity underpinned this initiative, the eventual selection of DCM specifically, was informed by more specific arguments that emerged during the modified DELPHI process. Firstly, as a condition with widespread under-recognition, capitalising on an increasing momentum shift since its proposal 8 (for example with international guidelines 43 ) was considered prudent. Further as a new term, it did not carry any legacy of misinterpretation. This would obviate the need to change existing views (for example on the definition of CSM), instead presenting a new solution 44 which would still be recognised as a disease (as opposed to a syndrome such as ‘cervical myelopathy’). Finally, the term ‘degenerative’ was popular amongst PwCM. Whilst there were concerns raised by professionals about the impact that such terms can have on patient expectation and engagement with rehabilitation, 45 PwCM felt it faithful to their disease and likely to help them bring acknowledgement of its implications to a lay audience, who can often underestimate their disability. 46

These arguments have precedent from other conditions. For example, the selection of a new name or definition has been used to re-educate around a condition. 20 An ongoing example is that of the International Association for the Study of Pain’s efforts to redevelop the classification of chronic pain, which has subsequently entered ICD version 11 with positive endorsements.29,47,48 Likewise the choice of terminology has implications for how a disease is perceived or prioritised.19,49,50 Whilst previous evidence has suggested this is more likely for descriptive terms (“chronic fatigue”) as opposed to those that are perceived as a disorder (“chronic fatigue syndrome”), this is also informed by the perception of the disease itself, with chronic conditions, affecting multiple systems, of uncertain aetiology and without treatment or requirement for a doctor, less likely to be prioritised.51–53 An example of well adopted change is overactive bladder syndrome, previously known as ‘urinary incontinence’ or ‘detrusor instability’. 54 Here its combined recognition as a disorder that could be easily interpreted contributed to a dramatic change in awareness. 55 This was likely well supported by industry and the arrival of new medical therapies.55,56

This therefore indicates that the terms themselves still require a definition to guide their interpretation. Our definition has attempted to reconcile the need to offer clarification on what DCM is (an essentialist approach) with the acknowledgement that exactly what defines DCM remains uncertain (a nominalist approach). Striking this balance is important, to ensure the definition can remain timeless and relevant. Whilst subclassification of DCM is undoubtedly relevant, the knowledge to inform such a taxonomy is yet to be determined. 5 Spinal disorders in general have likely suffered from adoption of an essentialist approach. The advent of imaging has enabled detailed visualisation of structural changes to the spine, which have become represented within ICD frameworks given their anatomical basis. 21 Often this pathology however is incidental, but its recognition will still lead to its attachment to an individual. A recognisable example is disc degeneration and lower back pain,57,58 which as evaluated in a recent trial from North America, may have detrimental implications for their outcomes. 59

DCM is a condition with many critical uncertainties. Creating a single unifying term, with a more nominalist definition should help address these. However, for this to occur, the next challenge will be ensuring widespread adoption. One hopes that the inclusive and iterative approach taken here, alongside the strong rationale for adopting a single term, will give the community confidence in its choice and aid implementation.60,61 However, additional measures will likely be crucial, such as its integration within ICD framework.20,22

Conclusions

A global, multistakeholder consensus process involving those with lived experience has selected DCM as the single unifying term for a progressive spinal cord injury due to narrowing of the cervical spinal canal.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for We Choose to Call it ‘Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy’: Findings of AO Spine Research objectives and Common Data Elements Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy, an International and Multi-Stakeholder Partnership to Agree a Standard Unifying Term and Definition for a Disease by Benjamin M. Davies, Danyal Z Khan, Kara Barzangi, Ahmad Ali, Oliver D. Mowforth, Aria Nouri, James S. Harrop, Bizhan Aarabi, Vafa Rahimi-Movaghar, Shekar N Kurpad, James D. Guest, Lindsay Tetreault, Brian K. Kwon, Timothy F Boerger, Ricardo Rodrigues-Pinto, Julio C. Furlan, Robert Chen, Carl Moritz Zipser, Armin Curt, James Milligan, Sukhivinder Kalsi-Rayn, Ellen Sarewitz, Iwan Sadler, Shirley Widdop, Michael G. Fehlings, and Mark R.N. Kotter in Global Spine Journal

Acknowledgements

This study forms part of a wider initiative to accelerate knowledge discovery that can improve outcomes in degenerative cervical myelopathy. This initiative was organized and funded by AO Spine through the AO Spine Knowledge Forum Spinal Cord Injury, a focused group of international spinal cord injury experts. More information can be found at aospine.org/recode. AO Spine is a clinical division of the AO Foundation, which is an independent medically-guided not-for-profit organization. Study support was provided directly through the AO Spine Research Department.

MRNK is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Brain Injury MedTech Co-operative based at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and University of Cambridge, and BMD a NIHR Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship. DZK is supported by an NIHR Academic Clinical Fellowship. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclaimer: This report is independent research arising from a Clinician Scientist Award, CS-2015-15-023, supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Benjamin M. Davies https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0591-5069

Oliver D. Mowforth https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6788-745X

Aria Nouri https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4965-3059

Timothy F Boerger https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1587-3704

Ricardo Rodrigues-Pinto https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6903-348X

Julio C. Furlan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2038-0018

Michael G. Fehlings https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5722-6364

References

- 1.Davies BM, Mowforth OD, Smith EK, Kotter MR. Degenerative cervical myelopathy. BMJ. 2018;360:k186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith SS, Stewart ME, Davies BM, Kotter MRN. The Prevalence of Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Spinal Cord Compression on Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Global spine journal. 2020;6(8):219256822093449. doi: 10.1177/2192568220934496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan DZ, Khan MS, Kotter M, Davies B. Tackling Research Inefficiency in Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: illustrating the current challenges for research synthesis. JMIR Research Protocols; 2019. Published online. 10.2196/15922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tracy JA, Bartleson JD. Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy. The Neurologist. 2010;16(3):176-187. doi: 10.1097/nrl.0b013e3181da3a29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badhiwala JH, Ahuja CS, Akbar MA, et al. Degenerative cervical myelopathy - update and future directions. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2020;16(2):108-124. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0303-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GA K. On paraplegia depending on the ligament of the spine. Guys Hospital Report. 1839;3:17-34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies BM, McHugh M, Elgheriani A, et al. The reporting of study and population characteristics in degenerative cervical myelopathy: A systematic review. PloS one. 2017;12(3):e0172564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nouri A, Tetreault L, Singh A, Karadimas SK, Fehlings MG. Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Epidemiology, Genetics, and Pathogenesis. Spine. 2015;40(12):E675-E693. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000000913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies BM, Starkey M. Raising Awareness. Myelopathy Matters. 2020;12(4). Published online October 20 https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/ao-spine-research-top-10-no-1-raising-awareness/id1493647316?i=1000495367740 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waqar M, Wilcock J, Garner J, Davies B, Kotter M. Quantitative analysis of medical students’ and physicians’ knowledge of degenerative cervical myelopathy. BMJ open. 2020;10(1):e028455. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pope DH, Mowforth OD, Davies BM, Kotter MRN. Diagnostic Delays Lead to Greater Disability in Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy and Represent a Health Inequality. Spine. 2020;45(6):368-377. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000003305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behrbalk E, Salame K, Regev GJ, Keynan O, Boszczyk B, Lidar Z. Delayed diagnosis of cervical spondylotic myelopathy by primary care physicians. Neurosurgical focus. 2013;35(1):E1. doi: 10.3171/2013.3.focus1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tetreault LA, Côté P, Kopjar B, Arnold P, Fehlings MG, Network AosNA, ICTR . A clinical prediction model to assess surgical outcome in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: internal and external validations using the prospective multicenter AOSpine North American and international datasets of 743 patients. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2015;15(3):388-397. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.12.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh T, Lafage R, Lafage V, et al. Comparing Quality of Life in Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy with Other Chronic Debilitating Diseases Using the SF-36 Survey. World neurosurgery. 2017;106:699-706. Published online January 5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.12.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scadding J. Essentialism and nominalism in medicine: logic of diagnosis in disease terminology. Lancet. 1996;348(9027):594-596. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02049-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toon PD. Defining `disease’—classification must be distinguished from evaluation. J Med Ethics. 1981;7(4):197-201. doi: 10.1136/jme.7.4.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scadding JG. Asthma and bronchial reactivity. Br Medical J Clin Res Ed. 1987;294(6580):1115-1116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6580.1115-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scadding JG. Principles of definition in medicine with special reference to chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Lancet. 1959;273(7068):323-325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(59)90308-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith R. In search of “non-disease. Bmj. 2002;324(7342):883-885. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan AJ. Medical Eponyms: Patient Advocates, Professional Interests and the Persistence of Honorary Naming. Soc Hist Med. 2016;29(3):534-556. doi: 10.1093/shm/hkv142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Earlam R. Körner, nomenclature, and SNOMED. Br Medical J Clin Res Ed. 1988;296(6626):903-905. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmann B. Complexity of the Concept of Disease as Shown Through Rival Theoretical Frameworks. Theor Med Bioeth. 2001;22(3):211-236. doi: 10.1023/a:1011416302494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearce JMS. Disease, diagnosis or syndrome? Pract Neurology. 2011;11(2):91-97. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2011.241802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies BM, Khan DZ, Mowforth OD, et al. RE-CODE DCM (Research Objectives and Common Data Elements for Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy): A Consensus Process to Improve Research Efficiency in DCM, Through Establishment of a Standardized Dataset for Clinical Research and the Definition of the Research Priorities. Global spine journal. 2019;9(1_suppl):65S-76S. doi: 10.1177/2192568219832855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boerger TF, Davies BM, Sadler I, Sarewitz E, Kotter MRN. Patient, sufferer, victim, casualty or person with cervical myelopathy: let us decide our identifier. Integrated Healthcare Journal. 2020;2(1):e000023. doi: 10.1136/ihj-2019-000023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan MA, Mowforth OM, Kuhn I, Kotter MRN, Davies BM. Development of a validated search filter for Ovid Embase for degenerative cervical myelopathy. Health Information Libr J. 2021;12373. Published online. doi: 10.1111/hir.12373. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34409722/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies BM, Goh S, Yi K, Kuhn I, Kotter MRN. Development and validation of a MEDLINE search filter/hedge for degenerative cervical myelopathy. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2018;18(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0529-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berlin R, Gruen R, Best J. Systems Medicine Disease: Disease Classification and Scalability Beyond Networks and Boundary Conditions. Frontiers Bioeng Biotechnology. 2018;6:112. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease. Pain. 2019;160(1):19-27. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Organisation WH. Content Model Reference Guide 11th Version; 2011. https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/revision/Content_Model_Reference_Guide.January_2011.pdf?ua=1. Accessed July 26, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grodzinski N, Grodzinski B, Davies BM. Can co-authorship networks be used to predict author research impact? A machine-learning based analysis within the field of degenerative cervical myelopathy research. Plos One. 2021;16(9):e0256997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nouri A, Cheng JS, Davies B, Kotter M, Schaller K, Tessitore E. Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: A Brief Review of Past Perspectives, Present Developments, and Future Directions. Journal of clinical medicine. 2020;9(2):535. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies BM, Starkey M. Naming Myelopathy. Myelopathy Matters. 2020. Published online March 15 https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/episode-3-naming-myelopathy/id1493647316?i=1000468510381 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stookey B. Compression of the Spinal Cord due to Ventral Extradural Cervical Chondromas: Diagnosis and Surgical Treatment. Archives Neurology Psychiatry. 1928;20(2):275-291. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1928.02210140043003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.PEET MM, ECHOLS DH. Herniation of the nucleus pulposus: a cause of compression of the spinal, cord. Archives Neurology Psychiatry. 1934;32(5):924-932. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1934.02250110012002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clarke E, Robinson PK. Cervical myelopathy: a complication of cervical spondylosis. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1956;79(3):483-510. doi: 10.1093/brain/79.3.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pope DH, Davies BM, Mowforth OD, Bowden AR, Kotter MRN. Genetics of Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Candidate Gene Studies. Journal of clinical medicine. 2020;9(1):282. doi: 10.3390/jcm9010282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang H, Liu G, Lu S, et al. Epidemiology of ossification of the spinal ligaments and associated factors in the Chinese population: a cross-sectional study of 2000 consecutive individuals. Bmc Musculoskelet Di. 2019;20(1):253. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2569-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nouri A, Martin A, Tetreault L, et al. MRI analysis of the combined prospectively collected AOSpine North America and International Data: The Prevalence and Spectrum of Pathologies in a Global Cohort of Patients with Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy. Spine. Published online November. 2016;16:1058-1067. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000001981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalb S, Martirosyan NL, Perez-Orribo L, Kalani MYS, Theodore N. Analysis of demographics, risk factors, clinical presentation, and surgical treatment modalities for the ossified posterior longitudinal ligament. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;30(3):E11. doi: 10.3171/2010.12.focus10265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.François RJ, Eulderink F, Bywaters EG. Commented glossary for rheumatic spinal diseases, based on pathology. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(8):615-625. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.8.615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tetreault L, Goldstein CL, Arnold P, et al. Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: A Spectrum of Related Disorders Affecting the Aging Spine. Neurosurgery . 2015;77(suppl 42):S51-67. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000000951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Riew KD, et al. A Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Patients With Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Recommendations for Patients With Mild, Moderate, and Severe Disease and Nonmyelopathic Patients With Evidence of Cord Compression. Global spine journal. 2017;7(3 suppl l):70S-83S. doi: 10.1177/2192568217701914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arroyo NA, Gessert T, Hitchcock M, et al. What Promotes Surgeon Practice Change? A Scoping Review of Innovation Adoption in Surgical Practice. Ann Surg. 2020;273(3):474-482. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000004355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart M, Loftus S. Sticks and Stones: The Impact of Language in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2018;48(7):519-522. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.0610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan DZ, Fitzpatrick SM, Hilton B, et al. Prevailing outcome themes reported by people with degenerative cervical myelopathy: findings from a focus group session (Preprint). Jmir Form Res. 2020;5(2):e18732. doi: 10.2196/18732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zinboonyahgoon N, Luansritisakul C, Eiamtanasate S, et al. Comparing the ICD-11 chronic pain classification with ICD-10: how can the new coding system make chronic pain visible? A study in a tertiary care pain clinic setting. Pain. 2021;162(7):1995-2001. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barke A, Korwisi B, Casser HR, et al. Pilot field testing of the chronic pain classification for ICD-11: the results of ecological coding. Bmc Public Health. 2018;18(1):1239. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6135-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stone J, Wojcik W, Durrance D, et al. What should we say to patients with symptoms unexplained by disease? The “number needed to offend. Bmj. 2002;325(7378):1449-1450. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karkazis K, Feder EK. Naming the problem: disorders and their meanings. Lancet. 2008;372(9655):2016-2017. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61858-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Norredam M, Album D. Review Article: Prestige and its significance for medical specialties and diseases. Scand J Public Healt. 2007;35(6):655-661. doi: 10.1080/14034940701362137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Campbell EJM, Scadding JG, Roberts RS. The concept of disease. Brit Med J. 1979;2(6193):757-762. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6193.757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young ME, Norman GR, Humphreys KR. The Role of Medical Language in Changing Public Perceptions of Illness. Plos One. 2008;3(12):e3875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hampel C, Wienhold D, Benken N, Eggersmann C, Thüroff JW. Definition of overactive bladder and epidemiology of urinary incontinence. Urology. 1997;50(6A suppl l):4-14. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00578-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cardona-Grau D, Spettel S. History of the Term “Overactive Bladder. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Reports. 2014;9(1):48-51. doi: 10.1007/s11884-013-0218-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elliott C. Black Hat, White Coat: Adventures on the Dark Side of Medicine; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okada E, Matsumoto M, Ichihara D, et al. Aging of the cervical spine in healthy volunteers: a 10-year longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Spine. 2009;34(7):706-712. doi: 10.1097/brs.0b013e31819c2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davies BM, Atkinson RA, Ludwinski F, Freemont AJ, Hoyland JA, Gnanalingham KK. Qualitative grading of disc degeneration by magnetic resonance in the lumbar and cervical spine: lack of correlation with histology in surgical cases. Published online March. 2016;21:1-8. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2016.1161174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jarvik JG, Meier EN, James KT, et al. The Effect of Including Benchmark Prevalence Data of Common Imaging Findings in Spine Image Reports on Health Care Utilization Among Adults Undergoing Spine Imaging: A Stepped-Wedge Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open. 2020;3(9):e2015713-e2015713. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A. Barriers and Strategies in Guideline Implementation—A Scoping Review. Healthc. 2016;4(3):36. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Correa VC, Lugo-Agudelo LH, Aguirre-Acevedo DC, et al. Individual, health system, and contextual barriers and facilitators for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines: a systematic metareview. Health Res Policy Sy. 2020;18(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00588-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for We Choose to Call it ‘Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy’: Findings of AO Spine Research objectives and Common Data Elements Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy, an International and Multi-Stakeholder Partnership to Agree a Standard Unifying Term and Definition for a Disease by Benjamin M. Davies, Danyal Z Khan, Kara Barzangi, Ahmad Ali, Oliver D. Mowforth, Aria Nouri, James S. Harrop, Bizhan Aarabi, Vafa Rahimi-Movaghar, Shekar N Kurpad, James D. Guest, Lindsay Tetreault, Brian K. Kwon, Timothy F Boerger, Ricardo Rodrigues-Pinto, Julio C. Furlan, Robert Chen, Carl Moritz Zipser, Armin Curt, James Milligan, Sukhivinder Kalsi-Rayn, Ellen Sarewitz, Iwan Sadler, Shirley Widdop, Michael G. Fehlings, and Mark R.N. Kotter in Global Spine Journal