Abstract

External technical assistance has played a vital role in facilitating the transitions of donor-supported health projects/programmes (or their key components) to domestic health systems in China and Georgia. Despite large differences in size and socio-political systems, these two upper-middle-income countries have both undergone similar trajectories of ‘graduating’ from external assistance for health and gradually established strong national ownership in programme financing and policymaking over the recent decades. Although there have been many documented challenges in achieving effective and sustainable technical assistance, the legacy of technical assistance practices in China and Georgia provides many important lessons for improving technical assistance outcomes and achieving more successful donor transitions with long-term sustainability. In this innovation and practice report, we have selected five projects/programmes in China and Georgia supported by the following external health partners: the World Bank and the UK Department for International Development, Gavi Alliance and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. These five projects/programmes covered different health focus areas, ranging from rural health system strengthening to opioid substitution therapy. We discuss three innovative practices of technical assistance identified by the cross-country research teams: (1) talent cultivation for key decision-makers and other important stakeholders in the health system; (2) long-term partnerships between external and domestic experts; and (3) evidence-based policy advocacy nurtured by local experiences. However, the main challenge of implementation is insufficient domestic budgets for capacity building during and post-transition. We further identify two enablers for these practices to facilitate donor transition: (1) a project/programme governance structure integrated into the national health system and (2) a donor–recipient dynamic that enabled deep and far-reaching engagements with external and domestic stakeholders. Our findings shed light on the practices of technical assistance that strengthen long-term post-transition sustainability across multiple settings, particularly in middle-income countries.

Keywords: External technical assistance, donor transition, sustainability, development assistance for health, China, Georgia, middle-income countries

Key messages.

External technical assistance is important in facilitating the transition from donor-supported health projects/programmes to domestic health systems, leaving long-lasting legacies.

In China and Georgia, two upper-middle-income countries ‘graduating’ from external support, external technical assistance highlights the importance of long-term close, committed and sustained donor–recipient relationships.

Three innovative practices of technical assistance identified are (1) talent cultivation for key decision-makers and other important stakeholders in the health system; (2) formation of long-term partnerships between external and domestic experts; and (3) evidence-based policy advocacy nurtured by local knowledge and experiences.

To optimize technical assistance towards post-transition sustainability, donor-supported projects/programmes should (1) help mobilize resources and encourage long-term investments for capacity-building; (2) help configure a governance structure integrated into the recipient’s health system; and (3) boost donor–recipient dynamics by enabling deep and far-reaching engagements with external and domestic stakeholders.

Introduction

Technical assistance (TA) is a dynamic knowledge transfer and/or capacity-building process for designing or improving the quality, effectiveness and/or efficiency of specific programmes, research, services, products or systems (West et al., 2012). The prevalence of TA activities in development assistance for health (DAH) offers a rich field to examine how international standards, knowledge and partnerships take root in national health systems. Especially for middle-income countries with growing economic capabilities and decreasing donor funding, TA entails sustaining improved health outcomes supported by DAH beyond money. Nevertheless, there have been documented challenges owing to donor–recipient power asymmetry (Khan et al., 2018), such as inadequate contextualization and reliance on external implementing partners (Knittel et al., 2022), limiting the effectiveness of TA and sustainability of activities previously supported by TA (DeCorby-Watson et al., 2018; Scott et al., 2022). An in-depth examination of TA practices may help improve TA outcomes and achieve successful donor transitions with long-term sustainability.

This report defines donor transition as ‘any major shift in policy, funding, or programming’ (McDade et al., 2020, p. 8) that aims to give the recipient country more or full responsibility in a donor-supported project/programme. We aim to summarize innovative practices of external TA commonly found in two upper-middle-income countries—China and Georgia. Despite large differences in size and socio-political system, both countries have undergone similar trajectories of donor transition with strong national ownership to adapt and scale up donor-supported practices and ideas. Looking at over two decades of TA in the critical progressive stages of national health system development in both countries since the late 1990s, we selected five projects/programmes supported by the following external partners: the World Bank (WB) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID, currently Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office), Gavi Alliance and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund). These projects/programmes cover different health focus areas, from rural health system strengthening to opioid substitution therapy (OST) provision (see Supplementary Material 1). We conducted 80 key informant in-depth interviews, reviewed 151 documents and analysed administrative data, triangulating across information sources (see Supplementary Material 2 for methods and Supplementary Material 3 for themes and quotes).

We summarize three innovative practices (Table 1) and demonstrate how technical and ideational changes enabled by donor-supported projects/programmes are generated, scaled up and eventually institutionalized. We identify that the key to successful TA for donor transition lies in long-term committed, sustained donor–recipient engagements.

Table 1.

A summary of innovative practices

| Practice | Implementation experience | Evidence from China | Evidence from Georgia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Talent cultivation for key decision-makers and other important stakeholders in the health system | Vertical alignment:

Wide coverage:

Multiple modalities:

|

World Bank (WB) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) Basic Health Services Project:

Gavi Hepatitis B vaccination project and Global Fund HIV/AIDS Rolling Continuation Channel project:

Three projects:

|

National Immunization Program (NIP) with Gavi:

Opioid substitution therapy (OST) programme with the Global Fund:

|

| Long-term partnerships between external and domestic experts | A long-term, accompanying and sustained approach for localizing external expertise:

|

WB/DFID project and Gavi project:

Gavi project:

|

NIP:

OST:

|

| Evidence-based policy advocacy nurtured by local experiences | Contextual analyses for better project/programme design, implementation and adjustment, as well as for informing policymaking Introduction of novel evidence-based research approaches to generate research evidence for policy and decision-making |

WB/DFID project:

Gavi project:

Global Fund project:

|

NIP:

OST:

|

Implementation

Talent cultivation for key decision-makers and other important stakeholders in the health system

In both countries, training and mentoring in TA were aligned with existing structures of the health system, especially targeting the project/programme decision-makers, managers and staff from/in the state institutions serving the health system. This approach amplified and prolonged the technical and ideational legacies of donor-funded projects/programmes. In both countries, experts from domestic institutes and universities cultivated by external TA further localized and disseminated these legacies through on-site training and mentoring to local officials, service providers and civil societies. Moreover, in China, the pass-on of these legacies coincided with the promotion of former project managers and staff, who simultaneously worked for health departments in the subnational or national government, into senior health decision-makers across national and subnational levels. An example is the Cooperative Medical Scheme (CMS), one of the China WB/DFID project’s components. External and domestic experts worked jointly to provide project management and health insurance training to CMS managers and staff. During donor transition, CMS was integrated into the national New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS). As the majority of these trained individuals went on to serve as subnational or national heads or managers of NCMS, CMS management knowledge was incorporated into NCMS.

Apart from traditional on-the-job training, external partners also adopted multiple modalities of talent cultivation and engaged various stakeholders, spanning from members of civil society organizations to health service providers, managers, officials and experts. In Georgia, external partners supported educational site visits as well as regional knowledge-sharing forums and workshops for key decision-makers and members of the two selected programmes, the National Immunization Technical Advisory Group, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Finance. In China, the selected projects supported short-term study tours and longer-term overseas research, courses or degrees. In both countries, external partners also helped establish educational programmes at higher educational institutions to continuously cultivate domestic public health talents (Yang et al., 2004; Chikovani and Gotsadze, 2022, p. 22).

This vertically progressive and wide-ranging investment in human resources laid a solid foundation to diffuse TA benefits and strengthen decision-making capacity across nearly all levels of the health system. On the practical level, managers and staff gained valuable programme management skills and engaged with decision-makers to identify mutually acceptable solutions. On the policymaking level, capacitated individuals gained experience in decision-making and became passionate advocates for the sustainability of donor-supported interventions in the health policymaking community. In both countries, these individuals in the health sector managed to mobilize the Ministry of Finance for budgets for donor-funded activities. Taken together, such talent cultivation has created major, life-long ideational changes. In the Global Fund cases in both countries, the spirit of multistakeholder collaboration, especially foregrounding civil society engagements (Huang and Jia, 2014; Soselia and Gotsadze, 2022, p. 23), has been widely acknowledged among former project/programme participants and institutionalized as common practices in the national HIV/AIDS responses. Thus, through influencing decision-making, the key stakeholders cultivated have broadened support for transitioning project/programme components into national health systems.

Long-term partnerships between external and domestic experts

‘Parachuting’ external researchers, consultants and advisors is common in global health (The Lancet Global Health, 2018)—these experts often only have a few one-off encounters with domestic counterparts. Our cases have nevertheless exemplified that building long-term partnerships between external and domestic experts is a worthy investment.

Through direct peer-to-peer knowledge sharing, coaching, mentorship and personal relationship building, long-term external–domestic expert partnerships could support the co-creation of flexible, suitable solutions for project/programme design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation that integrate local knowledge. Such partnerships could further facilitate summarizing and disseminating project/programme experience to domestic policymakers and practitioners as well as seamlessly incorporating international knowledge adapted locally into the national health system. China’s WB/DFID project has an expert group system in which international, national and subnational experts were paired up for long-term technical support (Liu et al., 2007, p. 138; World Bank Group, 2008, p. 22–3). Through this system, domestic experts have been professionalized in key project components theoretically and practically. Some domestic experts were involved in introducing new national or subnational policies piloted by the project, which facilitated incorporating the project experience into the policymaking process (Bloom et al., 2009). In Georgia, international experts worked long-term with the National Immunization Program (NIP) representatives to conduct NIP Joint Appraisals, ensuring mutual agreement on assessment findings and future actions for a smooth transition (Chikovani and Gotsadze, 2022, p. 17).

Moreover, long-term expert partnerships often outlast donor-funded projects/programmes, facilitating post-transition sustainability. After the WB/DFID project ended in 2007, the Chinese government consulted the WB experts for its forthcoming healthcare reform, reflecting the country’s willingness to pay for and continuously engage with external consultancy and enabling the incorporation of project experience into the reform policies (Wagstaff et al., 2009, p. 7). In the OST programme, Georgia has also established long-term cooperation with the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction ensuring continuous monitoring of five key drug dependency treatment indicators (Soselia and Gotsadze, 2022, p. 25).

Evidence-based policy advocacy nurtured by local knowledge and experiences

Engaging national governments through evidence-based policy advocacy has been critical in transitioning donor-funded pilots into national programmes and policies. Contextual analyses served this purpose by improving project design and implementation and, more importantly, convincing domestic health policymakers of the importance and feasibility of adopting new policies. The WB’s Analytical and Advisory Activities studies have analysed the context of China’s health sector since the 1990s. These analyses have enabled the WB to adopt a demand-driven model for its projects that targeted China’s key bottlenecks and informed national health policymaking (Wagstaff et al., 2009, p. 5–7).

TA also influences domestic policymaking by introducing evidence-based research approaches. In Georgia, the Global Fund’s size estimation studies for drug use helped advocate for OST needs to the government (Soselia and Gotsadze, 2022, p. 23). The Global Fund also supported empirical studies on the effectiveness of community-based interventions in China. These studies have been used as the basis for the multistakeholder approach in China’s national HIV/AIDS response (Country Coordinating Mechanism, P.R. China, 2008; Zhang et al., 2017). Similarly, WHO (Gavi’s partner) supported cost–benefit or cost analyses on NIPs in both countries. Complemented by informational and advocacy meetings, these analyses convinced the Chinese and Georgian governments to deploy new vaccines.

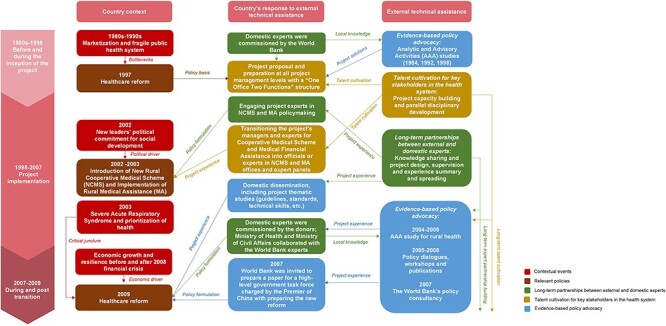

Evidence-based policy advocacy highlights the importance of local contexts and engagement with domestic partners. Although much of the technical expertise is part and parcel of international norms and standards (Eichler and Levine, 2009), localizing this expertise requires cultivating domestic advocates, forming long-term external–domestic expert partnerships and generating evidence. Using the China WB/DFID project as an illustrative case, we visualize the interactive mechanisms of these three pathways in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Technical assistance of the Basic Health Services Project supported by the World Bank and the UK Department for International Development in China (1998–2007)

Challenges

The abovementioned three innovative practices in both countries were implemented while facing some challenges, including those common in capacity-building activities, such as personnel movement and the subsequent brain drain. Some external partners were not fully involved in transferring international knowledge, hampering their consultancy’s usefulness and effectiveness.

A salient challenge in both countries was financing capacity-building activities from domestic budgets, which might have limited the impacts of TA (Knittel et al., 2022). Chinese poverty-stricken subnational authorities’ difficulty in fulfilling co-financing requirements limited their willingness to support capacity-building activities. Similarly, Georgia had limited national resources available to sustain these activities at the same level and scale as previously under donor support. Cross-country learning opportunities also dwindled unless external partners continued to support and organize events to offer such opportunities. One reason is that investment in these activities may require more time to create visible change than in service delivery or infrastructure.

Enablers

These TA practices and their contributions to donor transition have benefited from several enablers. The first was a project/programme governance structure largely integrated into the national health system, working with the public sector and the existing delivery infrastructure (Kleinman et al., 2013; Steurs, 2019). In both countries, a pre-existing office/organization was responsible for implementing donor-supported project/programme activities while performing daily jobs/duties in the health system assigned by national legislation. Through this structure, the project/programme-generated learnings were internalized and institutionalized by the national health system on a long-term, daily basis.

Another enabler was a donor–recipient dynamic with donors’ strong technical expertise and respect for domestic counterparts vis-à-vis the recipients’ willingness to learn from external partners. External partners were capable advocates and strongly preferred evidence-based knowledge generation and policymaking. Simultaneously, both countries have demonstrated a passionately open attitude towards forging international partnerships and learning from international ‘best practices’—they pursued modernization through scientific evidence, human-centred interventions, accountability and transparency. The domestic engagements were thus proactive since the donor-funded projects/programme inception, ensuring adaptation suiting local needs and systems (Shroff et al., 2022) and facilitating advocacy for smooth transitions. With deep and far-reaching engagements with external and domestic stakeholders to vitalize international knowledge in the local contexts, robust, continuous, long-term advocacy alliances between international, national, subnational and civil stakeholders were established, enabling wider coverage of services piloted by the donor-funded projects/programmes during and post-transition.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight three interrelated external TA practices: talent cultivation for key decision-makers and other important stakeholders in the health system, formation of long-term partnerships between external and domestic experts and evidence-based policy advocacy nurtured by local knowledge and experiences. These three lessons shed light on TA practices that strengthen long-term post-transition sustainability across multiple settings, particularly in middle-income countries. To optimize TA towards post-transition sustainability, donor-supported projects/programmes should help mobilize resources and encourage long-term investments for capacity-building, configure a governance structure integrated into the recipient’s health system and boost donor–recipient dynamics enabling deep and far-reaching engagements with external and domestic stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express deep gratitude to Dr Zubin Shroff, Dr Susan Sparkes and Dr Maria Skarphedinsdottir for their invaluable technical support during the implementation of the study. The authors are also grateful to the key informants for their invaluable cooperation and inputs, Angela Ying Xiao for language polishing and Taige Wang, Xuan Li, Shan Lu, Qingyu Hu and Nutsa Marjanishvili for their assistance in data collection.

This research also benefited from technical support from the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization, the Department of Health Systems Governance and Financing, World Health Organization and UHC 2030. Our sincere gratitude also goes to two anonymous reviewers for their professional comments and constructive suggestions. The authors would also like to thank Anas Ismail and Amanda Karapici from the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO for their help with proofreading the paper.

Footnotes

Approval on 15 July 2021, on the study protocol for ‘Sustaining effective coverage in the context of transition from external assistance – Lessons from China’.

Approval on 14 July 2021, on the study protocol for ‘Sustaining adequate coverage in the context of the transition from external assistance – Lessons from Georgia’.

Contributor Information

Aidan Huang, Vanke School of Public Health, Tsinghua University, No. 30 Shuangqing Road, Beijing 100084, China; Institute for International and Area Studies, Tsinghua University, No. 30 Shuangqing Road, Beijing 100084, China.

Chunkai Cao, Vanke School of Public Health, Tsinghua University, No. 30 Shuangqing Road, Beijing 100084, China.

Yingxi Zhao, Vanke School of Public Health, Tsinghua University, No. 30 Shuangqing Road, Beijing 100084, China; NDM Centre for Global Health Research, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3SY, UK.

Giorgi Soselia, School of Natural Sciences and Medicine, Ilia State University, Kakutsa Cholokashvili Ave 3/5, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia; Medecins Du Monde (France) South Caucasus Regional Program, 3 Elene Akhvlediani Khevi, Tbilisi 0102, Georgia.

Maia Uchaneishvili, School of Natural Sciences and Medicine, Ilia State University, Kakutsa Cholokashvili Ave 3/5, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia.

Ivdity Chikovani, School of Natural Sciences and Medicine, Ilia State University, Kakutsa Cholokashvili Ave 3/5, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia.

George Gotsadze, School of Natural Sciences and Medicine, Ilia State University, Kakutsa Cholokashvili Ave 3/5, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia.

Mohan Lyu, Vanke School of Public Health, Tsinghua University, No. 30 Shuangqing Road, Beijing 100084, China; Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University, 310 Trent Drive, Durham, NC 27708, United States of America.

Kun Tang, Vanke School of Public Health, Tsinghua University, No. 30 Shuangqing Road, Beijing 100084, China.

Abbreviations

AAA = Analytic and Advisory Activities

EMCDDA = European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction

CMS = Cooperative Medical Scheme

DAH = Development Assistance for Health

DFID = Department for International Development

NCMS = New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme

NIP = National Immunization Program

OST = Opioid Substitution Therapy

WB = World Bank

TA = Technical assistance

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Health Policy and Planning Journal online.

Data availability

The data derived from literature and documents from open source underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author. Other data cannot be shared for ethical and privacy reasons.

Funding

The research study is part of a multi-country research programme on understanding how to sustain effective coverage in the context of transition from external assistance supported by the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO in collaboration with the WHO Department of Health Systems Governance and Financing. The Alliance is supported through both core funding as well as project specific designated funds. The full list of Alliance donors is available here: https://ahpsr.who.int/about-us/funders.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the work: YZ, AH, CC, KT, GS, ICH, MU and GG; Data collection: AH, YZ, CC, KT, ML, GS, ICH; Data analysis and interpretation: AH, CC, YZ, GS, ICH, GG; Drafting the article: CC, AH, GG, GS, ICH, MU; Critical revision of the article: AH, CC, YZ, GG; AH and CC have contributed to the study equally, listed as co-lead authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Reflexivity Statement

This research is a collaboration between Chinese and Georgian researchers. The author group is inclusive, with five identified as women and four as men and five from China and four from Georgia. AH and CC are Chinese researchers with past research experiences in international development and public policy, particularly focusing on development assistance for health. YZ and KT are Chinese researchers with at least 7-year independent research experience in global health—they co-led the study design, supervised the research process in China, and exchanged with AH and CC every week to ensure multidisciplinary complementarity. These four researchers co-led the China team’s data collection with ML’s assistance. GG, one of the leading authors from the Georgia team, has almost 30 years’ experience in health policy and systems research on the global level and provided invaluable contributions to the study design and interpretation of findings. ICH has more than 25 years’ experience in public health, and GS has been an expert in the field for almost 10 years; both contributed to the study conceptualization, as well as data collection and analysis. MU, with more than 10 years of expertise in the field, participated in the study design and drafting of the paper and supported the team during the study implementation.

Meetings were held among the two teams to co-design the study and interpret the analysis. In both countries, document reviews were conducted before interviews to ensure researchers’ familiarity with the selected cases. Technically supported by Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization, the two countries shared a common analytical framework for developing the interview guides. Before the interviews, the researchers tailored the interview guides according to the participants’ perspectives and discussed how the researchers’ perspectives influenced the tailoring. Researchers’ backgrounds and affiliations were shared with participants prior to the interview. All researchers were independent of participants—neither superior nor subordinate to the latter. After each interview, researchers debriefed and discussed their perspectives and how previous experiences and interactions with the participants may influence their interpretation, to promote continued reflexivity. Mutual critical reviews were done within and between the two teams to ensure that the analyses were a true reflection of the data to minimize potential bias.

Ethical approval

This research has received ethics approval from the Institution Review Board of Tsinghua University (Project No: 20210095)1 and Georgia National Centre for Disease Control and Public Health (Letter # 2021–055)2.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bloom G, Liu Y, Qiao J. 2009. A partnership for health in China: reflections on the partnership between the Government of China, the World Bank and DFID in the China Basic Health Services Project. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies, 01–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chikovani I, Gotsadze G. 2022. National Immunization Program (NIP) transition from external assistance – case study from Georgia. Tbilisi, Georgia: Curatio International Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Country Coordinating Mechanism, P.R. China . 2008. Proposal Form: Rolling Continuation Channel. Geneva, Switzerland: Global Fund. [Google Scholar]

- DeCorby-Watson K, Mensah G, Bergeron K et al. 2018. Effectiveness of capacity building interventions relevant to public health practice: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 18: 684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler R, Levine R. 2009. Performance Incentives for Global Health: Potential and Pitfalls. Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Jia P. 2014. The Global Fund’s China Legacy. New York: Council on Foreign Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MS, Meghani A, Liverani M et al. 2018. How do external donors influence national health policy processes? Experiences of domestic policy actors in Cambodia and Pakistan. Health Policy and Planning 33: 215–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Basilico M, Jim Yong K et al. 2013. Reimagining Global Health: An Introduction. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, USA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knittel B, Coile A, Zou A et al. 2022. Critical barriers to sustainable capacity strengthening in global health: a systems perspective on development assistance. Gates Open Research 6: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Global Health . 2018. Closing the door on parachutes and parasites. The Lancet Global Health 6: e593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liu G, Liu M et al. 2007. Eds. Jiaqiang Zhongguo Nongcun Pinkun Diqu Jiben Weisheng Fuwu Xiangmu Wangong Zongjie Baogao [Final report on China Basic Health Services Project]. Beijing, China: China Financial & Economic Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- McDade KK, Schäferhoff M, Ogbuoji O et al. 2020. Transitioning away from donor funding for health: a cross cutting examination of donor approaches to transition. SSRN Journal. [Google Scholar]

- Scott VC, Jillani Z, Malpert A et al. 2022. A scoping review of the evaluation and effectiveness of technical assistance. Implementation Science Communications 3: 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff ZC, Sparkes S, Skarphedinsdottir M et al. 2022. Rethinking external assistance for health. Health Policy and Planning 37: 932–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soselia G, Gotsadze G. 2022. Sustaining Effective Coverage with Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) in Georgia in the Context of Transition from External Assistance. Tbilisi, Georgia: Curatio International Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Steurs L. 2019. European aid and health system strengthening: an analysis of donor approaches in the DRC, Ethiopia, Uganda, Mozambique and the global fund. Global Health Action 12: 1614371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff A, Lindelow M, Wang S et al. 2009. Reforming China’s Rural Health System. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- West GR, Clapp SP, Averill EMD et al. 2012. Defining and assessing evidence for the effectiveness of technical assistance in furthering global health. Global Public Health 7: 915–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group . 2008. Implementation completion and results report on a credit of SDR 63.0 million for the People’s Republic of China for a basic health services project. Washington, D.C: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Hu S, Yazbeck AS. 2004. WBI-China Health Sector Partnership: Fourteen Years and Growing. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Wang W, Sha S et al. 2017. Shehui Zuzhi Canyu Aizibing Fangzhi Jijin 2015 Nian Xiangmu Shenqing Yu Pizhun Qingkuang [Community-based organizations on application and approval of the projects supported by China AIDS Fund for non-governmental organizations in 2015]. Chinese Journal of AIDS & STD 23: 660–8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data derived from literature and documents from open source underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author. Other data cannot be shared for ethical and privacy reasons.