Abstract

Development assistance is a major source of financing for health in least developed countries. However, persistent aid fragmentation has led to inefficiencies and health inequities and constrained progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Malawi is a case study for this global challenge, with 55% of total health expenditure funded by donors and fragmentation across 166 financing sources and 265 implementing partners. This often leads to poor coordination and misalignment between government priorities and donor projects. To address these challenges, the Malawi Ministry of Health (MoH) has developed and implemented an architecture of aid coordination tools and processes. Using a case study approach, we documented the iterative development, implementation and institutionalization of these tools, which was led by the MoH with technical assistance from the Clinton Health Access Initiative. We reviewed the grey literature, including relevant policy documents, planning tools and databases of government/partner funding commitments, and drew upon the authors’ experiences in designing, implementing and scaling up these tools. Overall, the iterative use and revision of these tools by the Government of Malawi across the national and subnational levels, including integration with the government’s public financial management system, was critical to successful uptake. The tools are used to inform government and partner resource allocation decisions, assess financing and gaps for national and district plans and inform donor grant applications. As Malawi has launched the Health Sector Strategic Plan 2023–2030, these tools are being adapted for the ‘One Plan, One Budget and One Report’ approach. However, while the tools are an incremental mechanism to strengthen aid alignment, success has been constrained by the larger context of power imbalances and misaligned incentives between the donor community and the Government of Malawi. Reform of the aid architecture is therefore critical to ensure that these tools achieve maximum impact in Malawi’s journey towards UHC.

Keywords: Donor coordination, health financing, policy implementation, integration, strategic planning, efficiency, capacity building, developing countries, effectiveness, evidence-based policy

Key messages.

Development assistance is a major source of financing for health in least developed countries. However, persistent aid fragmentation has led to inefficiencies and health inequities and constrains progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Malawi is a case study for this global challenge, with 55% of total health expenditure funded by donors and fragmentation across 166 financing sources and 265 implementing partners. This often leads to a proliferation of vertical national strategic plans, poor coordination of donor funds and ultimately misalignment between the government’s health priorities and donor projects.

In this paper, we describe the Malawi Ministry of Health’s work to develop and implement an architecture of resource mapping and aid coordination tools, integrated into national and district planning and budgeting systems, in order to strengthen transparency and alignment of donor funding with government health priorities.

Overall, the iterative use and revision of these tools by the Government of Malawi across the national and subnational levels, including integration with the government’s public financial management system, were critical for successful uptake and institutionalization. The tools are used to inform government and partner resource allocation decisions, assess financing and gaps for national and district plans and inform donor grant applications. As Malawi has launched the Health Sector Strategic Plan 2023–2030, these tools are being adapted for the ‘One Plan, One Budget and One Report’ approach.

While the tools are an incremental mechanism to strengthen aid alignment, success has been constrained by the larger context of power imbalances and misaligned incentives between the donor community and the Government of Malawi. To address this, the tools would need to be complemented by stronger accountability mechanisms and leadership to enforce aid transparency and alignment with host government priorities. Reform of the global aid architecture is critical to ensure that these tools achieve maximum impact in Malawi’s journey towards UHC.

Introduction

Development assistance continues to play an important role in the provision of health across least developed countries (Duncan, 2020). However, aid is fragmented with donors investing in parallel systems to channel and deliver aid. This leads to inefficiencies and health inequities and constrains progress towards UHC (OECD, 2009; Siqueira et al., 2021). Multiple global initiatives such as the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005), International Health Partnership Plus (2007) and the Sustainable Development Goal 3 Global Action Plan (2019) have been launched, but with limited implementation success (Spicer et al., 2020).

At the country level, exercises such as the National Health Accounts (NHAs) have mapped funding flows, but are not ‘fit for purpose’ for forward-looking aid coordination as the NHA tracks retrospective expenditures rather than prospective budgets (WHO, 2018). There is therefore an ongoing need to equip and capacitate host governments with fit-for-purpose tools and processes for aid alignment.

Malawi is a key case study for this global challenge. Given its highly constrained macroeconomic context, Total Health Expenditure (THE) has stagnated at approximately $40 per capita, with the government contribution averaging 24% of THE over the last decade (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2022a). External aid accounts for 55% of THE (compared to a sub-Saharan African regional average of 22%) and contributes to as high as 80% of funding for vertical disease programmes such as HIV (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2022a; World Health Organization, 2023). Table 1 provides an overview of key health financing indicators in Malawi.

Table 1.

Key health financing indicators for Malawi

| Key health financing Indicators | 2017/18 FY | 2018/19 FY |

|---|---|---|

| GDP per capita (constant 2015 US$) | 379.9 | 386.1 |

| Total health expenditure (THE) as % of GDP | 9.8% | 8.8% |

| Current health expenditure per capita (at nominal US$ exchange rate) | 39.5 | 39.9 |

| General government expenditure for health (GGHE) per capita (at average US$ exchange rate) | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Donor expenditure on health as a % of THE | 57.6% | 55% |

| GGHE as % of THE | 24.4% | 24.1% |

| GGHE as % of general government expenditure | 9.5% | 8.4% |

Source: GDP per capita from the World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD?end=2021&locations=MW&start=2010 (23 June 2023, date last accessed); remaining data adopted from: Government of the Republic of Malawi. National Health Accounts Report for Fiscal Year 2018/2019. Lilongwe, 2022.

Furthermore, fragmented and verticalized donor funding has contributed to the proliferation of over 50 National Strategic Plans (NSPs), which leads to inefficiencies across the health system. For example, 514 in-service training activities were reported by partners in Fiscal Year (FY) 2019/2020. This directly impacts service delivery with 26% of health worker absences attributed to these trainings and exacerbates an existing 49% shortage of health workers (Dirk et al., 2011; Berman et al., 2022). Furthermore, fragmentation drives duplicative administrative expenses, representing 27% of THE in FY 2018/2019 with 65% of this expenditure coming from non-state actors (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2022a).

Through a case study approach, we documented the Ministry of Health (MoH)’s journey to develop and implement an architecture of aid coordination tools, integrated into national and district planning and budgeting systems. We conducted a review of the grey literature, including relevant policy documents, planning tools and databases of government/partner funding commitments. Furthermore, the authors draw upon their direct experiences in developing, implementing and iteratively scaling up these tools and processes.

Implementation

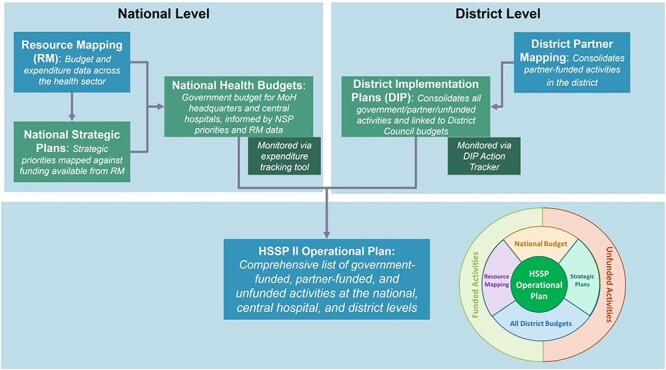

We documented three components of Malawi’s aid coordination architecture that serve to strengthen transparency and alignment of partner funding (Figure 1). The first is annual Resource Mapping (RM) exercises, implemented by the MoH since 2011, which collect and consolidate standardized budget and expenditure data across an estimated 166 financing sources and 265 implementing partners in the health sector (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2022b). This provides the government visibility into total funding for health over time, disaggregated by financing source, implementing agent, disease areas, geography, cost inputs and alignment to national strategic plans, (Yoon et al., 2021). RM results are integrated into the national MoH budgeting processes and provide MoH departments with visibility into complementary partner funding streams. Data collection for the RM exercise is also harmonized with the WHO’s NHAs and National AIDS Spending Assessment (NASA) to ensure efficiencies in resource tracking (Yoon et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

Framework of tools used for aid coordination and planning in Malawi

Note: DIP, District Implementation Plans; RM, Resource Mapping; HSSP, Health Sector Strategic Plan; NSPs, National Strategic Plans; MOH, Ministry of Health.

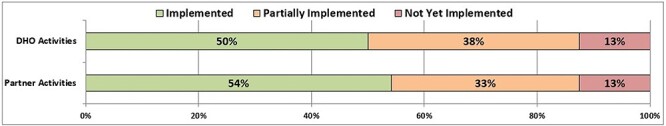

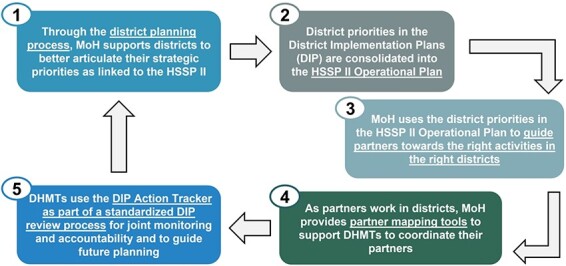

Second, the national RM exercise is complemented by similar subnational processes to track partner funding against District Implementation Plans (DIPs). A partner mapping tool was developed to collect and consolidate district partner activities and to integrate them into the DIP so that all government-funded, partner-funded, and unfunded activities were consolidated into a single district plan. To strengthen mutual accountability between government and partners, the DIP Action Tracker was subsequently developed as a monitoring tool that systematically tracks quarterly implementation progress against prioritized DIP health indicators and activities by both government and partners (Figure 2). This suite of subnational planning and aid coordination tools was scaled across 29 districts starting in FY 2019/2020.

Figure 2.

Illustrative example from the District Implementation Plan (DIP) Action Tracker showing the implementation status of the DIP by funding source

Note: DHO, District Health Office.

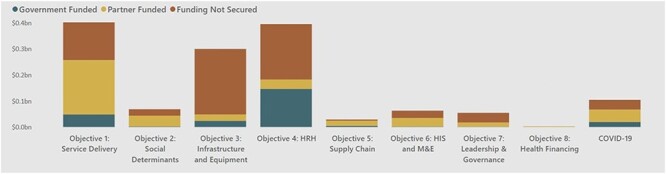

Third, to enable sector-wide planning and aid coordination across all levels of the health system, since FY 2019/2020, the MoH has developed Operational Plans (OP) against the Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP II), which consolidates all government-funded, partner-funded and unfunded priorities in the health sector, leveraging the outputs from the aid coordination tools described above. In FY 2020/2021, the HSSP II OP database included 43 data sources and over 37 000 activities at the national and district levels, which were costed, prioritized, mapped and consolidated into a single database that is updated annually. Over $1.4 billion of activities were mapped, of which $246 million were government-funded, $429 million were partner-funded and $739 million remained unfunded (Figure 3). Thirty-six percent of the unfunded costs were identified to be a high priority (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2021). Since 2022, results were visualized in an interactive dashboard on the MoH website to ensure public transparency on emerging evidence on funding gaps for key priorities (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2023b). The HSSP II OP therefore serves as a ‘one stop’ data solution by consolidating fragmented NSPs, government budgets and partner funding commitments into a single database which can be leveraged for policy decisions.

Figure 3.

The HSSP II Operational Plan consolidates district priorities from the DIPs in order to better link national and district aid coordination

Note: HSSP, District Health Office; DIP, District Implementation Plans; DHMT: District Health Management Team.

Achievements/challenges

This suite of practical tools has supported the Government of Malawi and its partners to operationalize their commitments for aid alignment and transparency.

In 2023, the MoH launched its HSSP III for 2023–2030, with the ‘One Plan, One Budget and One Report’ framework adopted as the overall guiding principle for aid coordination (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2023a). Evidence from the RM data and the HSSP II OP illustrated high levels of fragmentation and donor dependency and has supported momentum from government and donor stakeholders around the ‘One Plan, One Budget and One Report’ reform. In addition, RM data enabled the government to identify the 10 largest donors that provide over 90% of health funding and thereby better target stakeholder engagement around the reform (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2022b).

Furthermore, limited and plateauing health sector resources from both partners and government enabled consensus on the need for rigorous prioritization of HSSP III. Though the full HSSP III costs were estimated at $4.0 billion in FY 2024/2025, activities were consultatively prioritized to fit within the health sector resource envelope of $537 million in fungible funds, based on evidence from RM (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2022b; 2023a).

In addition, the tools’ flexibility enabled quick adaptation for emergencies, such as for aid coordination of the National COVID-19 Response and Preparedness Plan, launched in April 2020. The existing RM tool was rapidly realigned to launch a COVID-19 RM exercise in the second half of 2020, building off existing government and partner familiarity with RM tools and templates. Leveraging this data, the COVID-19 response team used a live COVID-19 RM dashboard to mobilize and coordinate funding against gaps in the National COVID-19 Plan (Figure 4). The District Health Management Teams from all 29 districts also developed COVID-19 activities, which were prioritized and integrated into their DIPs alongside funding information for essential health services (Yoon et al., 2021).

Figure 4.

Illustrative example from the HSSP II Operational Plan with the annual cost and funding status by HSSP II objective

Note: HRH, Human Resources for Health; M&E, Monitoring and Evaluation; HIS, Health Information System.

Despite these successes, one ongoing limitation is partners’ responsiveness in providing transparent financing information. This is particularly true at the subnational level where response rates from partners average only 29% across seven sampled districts compared to national RM response rates of 72% (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2022b). In Blantyre district, introduction of the revised DIP partner mapping tools in FY 2019/2020 led to an 800% increase in the number of district partners reporting their funding, but this was only 15% of the reported partner funding to Blantyre from the national RM, suggesting significant underreporting at the district level (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2019; 2020a).

Overall, this is indicative of broader challenges where donors and implementing partners do not have clear lines of accountability to the Government of Malawi (GoM), with weak mechanisms to enforce sanctions on partners who do not provide funding transparency. The tools are therefore an incremental improvement within the existing aid architecture but are constrained by broader power imbalances between donors and their host governments. To address this, the tools would need to be complemented by stronger accountability mechanisms and leadership to enforce aid transparency and alignment with host government priorities.

A second limitation is that strengthened national and district planning tools do not necessarily translate into improved service delivery due to scarce health sector resources. There is limited potential for domestic resource mobilization by the GoM, which prioritizes funding for the health sector at 8% of general government expenditures (compared to an average of 6% for low-income countries) but faces macroeconomic constraints to mobilize significant additional funding (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2018; 2022a). The strengthened plans therefore may not necessarily translate into improved health outputs or outcomes.

Third, the tools enhance prospective planning, but do not monitor retrospective expenditures in line with the initial budget commitments from donors and government. Despite improved coordination, there may still be a gap between theoretical budget commitments and actual implementation. This can be addressed through closer integration with retrospective expenditure tracking exercises such as NHAs. The Malawi MoH has therefore championed harmonized data collection and data analysis for RM, NHA, and NASA since 2019 (Yoon et al., 2021).

Enablers/constraints

Key enablers of sustainability were the iterative use and revision of these tools by the GoM across the national and district levels, including integration with the Public Financial Management system, interoperability of tools across the aid coordination architecture and simplification and adaptation for user-friendliness. For instance, 95% of district staff reported that the FY 2020/2021 DIP tool had improved from the previous year due to these iterative revisions. Furthermore, observations from Blantyre and Phalombe districts indicated that the planning process was reduced in length by 50–70% as the DIP tools were continually simplified to be ‘fit for purpose’ and to remove extraneous data collection that was not critical for policy decisions (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2020b).

A second key enabler was long-term institutional investment by the MoH and its technical partners. The MoH invested over 12 years to develop and refine the aid coordination architecture, starting with the national RM exercise in 2011. Subsequently, many years of testing and bottom-up feedback from end users, particularly at the district level, were required to streamline and refine the tools. Meanwhile, the technical assistance teams that supported the MoH were funded by multiple phases of long-term grants that enabled relationship-building and institutional memory required to successfully develop ‘fit for purpose’ tools tailored to the local context.

Key constraints included turnover of staff at both government and technical assistance partners, hindering long-term institutionalization and knowledge transfer. For instance, on average only 43% of team members that participated in any given RM exercise continued to provide technical support to the subsequent RM exercise the following year, while the remaining 57% transitioned into a new role (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2020a). To mitigate this challenge, extensive standard operating guidelines, procedures and documentation were developed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Knowledge management Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and guidelines developed for the aid coordination architecture

| Resource mapping | District planning tools | HSSP OP |

|---|---|---|

| Roadmap template | Guidelines for district health planning | DIP data entry SOP |

| Submission tracker and submission management protocol | Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and decision tree for the DIP tool | Database standardization SOP |

| Data entry training materials for enumerators | DIP tool customization SOP | |

| Data consolidation tool | District Health Information Software 2 bottleneck analysis application manual | |

| Data consolidation SOP | Causal analysis aid | |

| Database standardization SOP | Training videos on the DIP tool and DIP Action Tracker | |

| Removal of double-counting SOP | DIP Review SOP | |

| Analysis template | ||

| Analysis training template | ||

| Report template |

Another key constraint is limited computer literacy among end users, particularly in district settings which may lack the basic Excel skills that are required to effectively use and manipulate the tools. To mitigate this, a participatory, competency-based Excel curriculum was developed, and focal districts were trained on fundamental Excel skills to effectively utilize planning and coordination tools.

Conclusions

Several key lessons for health policy practitioners emerge from this work.

First, in highly fragmented donor-funded contexts, partner mapping is critical to ensure transparency of health resources and ultimately move towards joint planning between government and partners.

Second, policy practitioners should ensure that tools are ‘fit for purpose’ to meet specific evidence needs of policymakers. Iterative simplification, particularly to remove extraneous data collection not critical for policy decisions, was key to accelerating institutionalization and uptake of the aid coordination architecture.

However, while these tools have increased data transparency, the challenges of aid coordination extend beyond the boundaries of Malawi and link to the global incentive mechanisms and mandates of donors (Arne, 1999; OECD, 2003; Wood et al., 2011; Mwisongo and Nabyonga-Orem, 2016; Pallas and Ruger, 2017; Adhikari et al., 2019). Driven by achieving programmatic targets, donors have focused on creating parallel vertical systems, which in turn constrains the host government’s ability to create an equitable and rational financing system across the country. This has over time led to inefficiencies in health spending, inequity and fragmentation of service delivery and underinvestment in country health systems (Arne, 1999; OECD, 2003; Wood et al., 2011; Mwisongo and Nabyonga-Orem, 2016; Pallas and Ruger, 2017; Adhikari et al., 2019).

These tools are therefore an incremental mechanism to strengthen aid coordination, but are constrained by the larger context of power imbalances and misaligned incentives between the donor community and the Government of Malawi. Strengthened leadership to enforce accountability mechanisms between donors and host governments, complemented by wider reform of the global aid architecture, is critical to ensure that these tools achieve maximum impact in Malawi’s journey towards UHC.

Acknowledgment

The authors would also like to thank Anas Ismail and Amanda Karapici from the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO for their help with proofreading the paper.

Contributor Information

Lalit Sharma, Health Systems Strengthening, Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), Lilongwe, Private Bag 341, Malawi.

Stephanie Heung, Sustainable Health Financing and Health Workforce, Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), Lilongwe, Private Bag 341, Malawi.

Pakwanja Twea, Department of Planning and Policy Development, Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Ian Yoon, Former Health Systems Strengthening, Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), Lilongwe, Private Bag 341, Malawi.

Jean Nyondo, Department of Planning and Policy Development, Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Dalitso Laviwa, Sustainable Health Financing, Clinton Health Access Initiative, Blantyre, Private Bag 341, Malawi.

Kenasi Kasinje, Department of Planning and Policy Development, Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Emilia Connolly, Partnerships, Policy and Advocacy, Partners In Health, Neno, Malawi.

Dominic Nkhoma, Health Economics and Policy Unit, Kamuzu University of Health Sciences, Blantyre, Malawi.

Madalitso Chindamba, Department of Planning and Policy Development, Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Mihereteab Teshome Tebeje, Health Systems Strengthening, Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), Lilongwe, Private Bag 341, Malawi.

Eoghan Brady, Health Financing, Clinton Health Access Initiative, Boston, Massachusetts 02127, United States.

Andrews Gunda, Country Director, Clinton Health Access Initiative, Lilongwe Private Bag 341, Malawi.

Emily Chirwa, Department of Planning and Policy Development, Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Gerald Manthalu, Department of Planning and Policy Development, Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Abbreviations

BMGF = Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

CHAI = Clinton Health Access Initiative

DA = Development Assistance

DC = District Council

DHIS2 = District Health Information System 2

DIP = District Implementation Plans

DHO = District Health Office

DPPD = Department of Planning and Policy Development

FY = Fiscal Year

FAQs = Frequently Asked Questions

GDP = Gross Domestic Product

GGHE = General Government Expenditure for Health

HPP = Health Policy and Planning (Journal)

HSS = Health Systems Strengthening

HSSP = Health Sector Strategic Plan

MoH = Ministry of Health

MWK = Malawi Kwacha

NASA = National AIDS Spending Assessment

NHAs = National Health Accounts

NSPs = National Strategic Plans

OP = Operational Plan

PFM = Public Financial Management

PIH = Partners In Health

RM = Resource Mapping

SDGs = Sustainable Development Goals

SIDA = Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency

SOPs = Standard Operating Procedures

SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa

THE = Total Health Expenditure

UHC = Universal Health Coverage

UNICEF = United Nations Children’s Fund

WHO = World Health Organization

DHMT = District Health Management Team

HRH = Human Resources for Health

M&E = Monitoring and Evaluation

HIS = Health Information System

Data availability

The data referenced in this article are available on Ministry of Health, Malawi website at https://www.health.gov.mw/.

Funding

This work was primarily supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, UNICEF and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Author contributions

L.S., S.H., P.T., I.Y., J.N., D.L., K.K., E.C., D.N., and M.C. were involved in data collection and performed data analysis and interpretation. S.H., P.T., I.Y., E.C., and G.M. were responsible for the conception or design of the work. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the article.

Reflexivity Statement

The authors include six females and nine males and span multiple levels of seniority. All co-authors have extensive experience in health financing, health policy and health system strengthening in Malawi, either working directly for the Malawi MoH (seven co-authors), in local academia (one co-author) or as long-term providers of technical assistance to the government (seven co-authors). All 15 co-authors are either currently or previously based in Malawi.

In particular, the co-author list was selected to include policymakers who lead the government’s aid coordination efforts (including the Deputy Directors of the Malawi MoH’s Department of Planning and Policy Development) and the implementation teams who develop tools to map and align external funding. The authors therefore draw upon their direct experiences in developing, implementing and iteratively scaling up these tools and processes.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the paper was not required as it is based on a case study approach which primarily leverages review of grey literature, including relevant policy documents, planning tools and databases of government/partner funding commitments. The paper also draws on authors’ experiences in developing, implementing and iteratively scaling up these tools and processes, but formal qualitative interviews were not conducted.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- Adhikari R, Sharma JR, Smith P, Malata A. 2019. Foreign aid, Cashgate and trusting relationships amongst stakeholders: key factors contributing to (mal) functioning of the Malawian health system. Health Policy and Planning 34: 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arne D. 1999. Aid coordination and aid effectiveness. Aid Coordination and Coordination Experiences. Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 21–6.

- Berman L, Prust ML, Maungena Mononga A et al. 2022. Using modeling and scenario analysis to support evidence-based health workforce strategic planning in Malawi. Human Resources for Health. BMC 20: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirk HM, Douglas L, Arnab A, Natasha P. 2011. Constraints to implementing the essential health package in Malawi. PLOS One 6: e20741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan K. 2020. Aid spent on health: ODA data on donors, sectors, recipients. Development Initiatives [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Malawi . 2018. Malawi health financing systems assessment. Lilongwe: GOM. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Malawi . 2019. Blantyre district implementation plan for FY 2019/2020. Blantyre: GOM. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Malawi . 2020a. Health sector resource mapping round 6. Lilongwe: GOM. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Malawi . 2020b. Blantyre and Phalombe DIP post-workshop questionnaires in FY 2020/2021. GOM. Unpublished raw data.

- Government of the Republic of Malawi . 2021. Health sector strategic plan II operational plan for financial year 2020-2021. Lilongwe. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Malawi . 2022a. National health accounts report for fiscal year 2018/2019. Lilongwe: GOM. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Malawi . 2022b. Health sector resource mapping round 7 database for FY 2018/2019 to FY 2022/2023. Lilongwe: GOM. Unpublished dataset. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Malawi . 2023a. Health Sector Strategic Plan III (2017–2022): Reforming for Universal Health Coverage. Lilongwe: GOM. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Malawi . Dashboard for the HSSP II Operational Plan for Fiscal Year 2020/2021. http://www.health.gov.mw/index.php/directorates/planning-and-policy-development/hssp-dashboard, accessed 20 January 2023b.

- Mwisongo A, and Nabyonga-Orem J. 2016. Global health initiatives in Africa – governance, priorities, harmonisation and alignment. BMC Health Services Research 16: 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2003. Harmonising donor practices for effective aid delivery. Framework for Donor Co-operation. OECD Publishing.

- OECD . 2009. Development co-operation report 2009. How Fragmented Is Aid. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pallas SW, Ruger JP. 2017. Effects of donor proliferation in development aid for health on health program performance: A conceptual framework. Social Science & Medicine 175: 177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira M, Coube M, Millett C et al. 2021. The impacts of health systems financing fragmentation in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review protocol. BMC Syst Rev. 10: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer N, Agyepong I, Ottersen T et al. 2020. ‘It’s far too complicated’: why fragmentation persists in global health. Globalization and Health 16: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2018. How have health accounts data been used to influence policy?. https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Resource_Tracking_Brief_Map.pdf.

- Wood B , Betts J, Etta F et al. 2011. The evaluation of the Paris declaration. Final Report. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Global Health Expenditure Database. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en, accessed 20 January 2023.

- Yoon I, Twea P, Heung S et al. 2021. Health sector resource mapping in malawi: sharing the collection and use of budget data for evidence-based decision making. Global Health: Science and Practice 9: 793–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data referenced in this article are available on Ministry of Health, Malawi website at https://www.health.gov.mw/.