Abstract

As countries transition from external assistance while pursuing ambitious plans to achieve universal health coverage (UHC), there is increasing need to facilitate knowledge sharing and learning among them. Country-led and country-owned knowledge management is foundational to sustainable, more equitable external assistance for health and is a useful complement to more conventional capacity-building modalities provided under external assistance. In the context of external assistance, few initiatives use country-to-country sharing of practitioner experiences, and link learning to receiving guidance on how to adapt, apply and sustain policy changes. Dominant knowledge exchange processes are didactic, implicitly assuming static technical needs, and that practitioners in low- and middle-income countries require problem-specific, time-bound solutions. In reality, the technical challenges of achieving UHC and the group of policymakers involved continuously evolve. This paper aims to explore factors which are supportive of experience-based knowledge exchange between practitioners from diverse settings, drawing from the experience of the Joint Learning Network (JLN) for UHC—a global network of practitioners and policymakers sharing experiences about common challenges to develop and implement knowledge products supporting reforms for UHC—as an illustration of a peer-to-peer learning approach. This paper considers: (1) an analysis of JLN monitoring and evaluation data between 2020 and 2023 and (2) a qualitative inquiry to explore policymakers’ engagement with the JLN using semi-structured interviews (n = 14) with stakeholders from 10 countries. The JLN’s experience provides insights to factors that contribute to successful peer-to-peer learning approaches. JLN relies on engaging a network of practitioners with diverse experiences who organically identify and pursue a common learning agenda. Meaningful peer-to-peer learning requires dynamic, structured interactions, and alignment with windows of opportunity for implementation that enable rapid response to emerging and timely issues. Peer-to-peer learning can facilitate in-country knowledge sharing, learning and catalyse action at the institutional and health system levels.

Keywords: Peer-to-peer learning, joint learning, knowledge exchange, decolonizing global health

Key messages.

The challenges of achieving universal health coverage (UHC) are both context-specific and held in common across countries; policymakers benefit from the experience-based knowledge of practitioners in other settings and from participatory knowledge production processes which build capacity to address future challenges.

Among other well-known networks, the Joint Learning Network (JLN) for UHC has engaged in country-driven, peer-to-peer learning approaches, convening a dynamic global network of practitioners and policymakers from middle-to-low income countries to share their experiences about common challenges, and to develop and implement knowledge products that are supportive of UHC reforms.

A foundation of peer-to-peer learning is the engagement of a network of practitioners with diverse experiences and shared interests and the identification of common needs and priorities across these practitioners.

Ensuring that knowledge sharing is just-in-time to meet the windows of opportunity for implementation is key to successful peer-to-peer learning.

Introduction

Knowledge sharing and learning among policymakers to achieve universal health coverage (UHC) is of increasing importance as countries transition from external assistance. Dominant knowledge exchange processes implicitly assume technical needs are static and require problem-specific, time-bound solutions. However, policymakers work in a context of ever-evolving technical and political challenges and benefit from experience-based knowledge shared by practitioners from diverse settings and from participatory knowledge production processes which build capacity in addressing future challenges (Lagomarsino et al., 2012; Khan et al., 2018; Schneider et al., 2019). Further, as Shroff et al., (2022) highlight, external assistance typically focuses on externally established priorities. This is inappropriate in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), illustrated during the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, as countries responded to rapidly evolving crises amidst limited formal knowledge options (Gadsden et al., 2022).

A 2015 review of knowledge management practices by multi-stakeholder partnerships found that the design and impact of knowledge sharing within the context of external assistance was under-researched (Atkisson, 2015). The review found that a minority of the 64 partnerships (22%) included facilitated or self-moderated communities of practice, defined as an ongoing group exchange among practitioners. The dominant model of knowledge exchange applies didactic methods, where content is driven by published research or existing donor-developed tools (Wilson, 2007; Atkisson, 2015; Brownson et al., 2018; Juckett et al., 2022; Voller et al., 2022). In the context of external assistance, few initiatives use country-to-country sharing of practitioner experiences and link learning to receiving guidance on how to adapt, apply and sustain policy changes (Asamani and Nabyonga-Orem, 2020). A notable example of such an initiative is the Evidence-informed Policy Network which engages regional networks of policymakers to access research evidence, convene on locally-relevant issues and produce evidence briefs (Mansilla et al., 2017; Lester et al., 2020).

The focus of this paper is the Joint Learning Network (JLN) which aims to enable country-driven, peer-to-peer learning approaches, convening a global network of practitioners and policymakers to share experiences about common challenges and develop and implement knowledge products to support UHC reforms. This paper explores factors which are supportive of experience-based knowledge exchange between practitioners from diverse settings, drawing from the authors’ collective experience working with the JLN, as well as an analysis of JLN monitoring and evaluation data between 2020–2023 and feedback from semi-structured interviews with over a dozen JLN stakeholders from 10 countries about policymakers’ engagement with the JLN. Though other learning networks exist, our aim is to offer reflections based on the experience and evidence of the JLN, as an illustration of a peer-to-peer learning approach, and to identify key factors that can promote meaningful cross-country knowledge exchange, especially as countries transition from external assistance.

Implementation

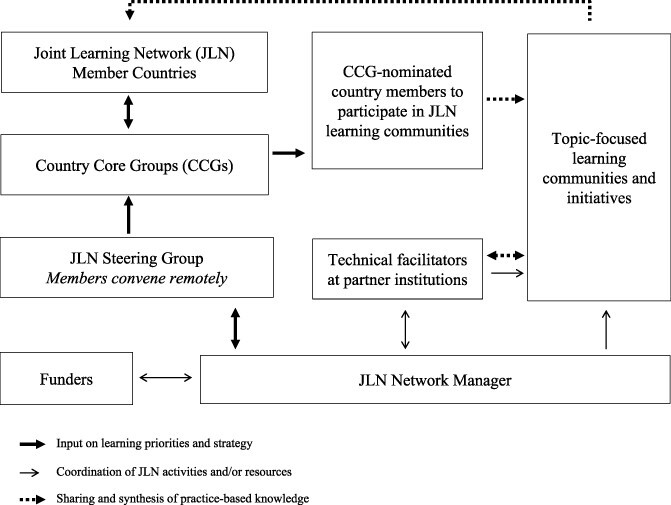

The JLN is a country-led, implementation-focused network that focuses on practitioner-to-practitioner learning to implement solutions to common challenges related to UHC. The JLN was established in 2010 in recognition that countries with diverse health systems and political contexts were facing similar challenges in achieving UHC (Nachuk et al., 2021). The network was launched with six member countries—growing to 36 in 2023—and has consistently relied on its members to identify priority learning areas. The JLN is guided by a central organizing body—a Steering Group (SG)—predominantly comprising of representatives from member countries. The SG solicits input from bodies of multi-stakeholder representatives within member countries—Country Core Groups (CCGs)—to identify technical priorities, establish communities of practice and facilitate country participation (Figure 1). The JLN is funded through donor grants managed by a Network Manager that constitutes the secretariat. The Network Manager implements the SG’s strategic direction, and coordinates with technical institutions managing learning communities. JLN’s impact is achieved primarily through countries deploying domestic resources to adapt and implement JLN’s knowledge products within their health systems. Donor financing is therefore modest in size and catalytic in nature.

Figure 1.

Governance structure of the Joint Learning Networka

aFigure adapted from Joint Learning Network 2023 Steering Group Meeting. JLN’s Governance Structure. London, 2023.

Communities of practice are managed by technical institutions which bring subject-matter expertise. Participants—policymakers and practitioners nominated to JLN learning communities by their respective CCGs—identify common topics and themes to cover over the two-year duration of the learning experience. Learning exchange is facilitated within communities, where health system leaders from member countries gather to learn together and exchange knowledge with the goal of improving health systems. Though most meetings are virtual, participants are invited to in-person meetings and the JLN covers the cost of attendance, when possible. There are no additional monetary benefits, but participants have reported advantages like recognition, confidence and career advancement. Learning is synthesized into practical how-to guidance and publicly available knowledge products intended to be useful to countries navigating UHC reform.

Achievements and enablers

The JLN has engaged policymakers and practitioners across over 50 joint learning technical teams, each focused on a technical priority identified by member countries. Routine monitoring of membership identified more than 850 unique people engaged in technical teams of the JLN in the last three years alone, of which more than half came from Ministries of Health or Finance. The JLN reaches those positioned to make critical decisions: surveys of members indicate a quarter of all participants hold leadership roles in civil service.

The JLN aims to support implementation-focused learning, by facilitating timely conversations among country stakeholders and across peer countries. For example, in Indonesia, the JLN has enabled improved coordination across key UHC stakeholders and is supporting the national social security agency with real-time knowledge from peer countries in ongoing reforms to improve the efficiency, quality and sustainability of its national health insurance programme (Mukti, 2023).

The JLN’s outputs—known as knowledge products—aim to be practical and co-developed by JLN members from countries facing similar UHC challenges. Examples of successful knowledge creation are the Costing Manual (Özaltın and Cashin, 2014), Provider Payment Mechanism Assessment Manual (Cashin, 2015) and Messaging Guide for Domestic Resource Mobilization (Tandon et al., 2021) which have been widely used in JLN and non-JLN countries. To date, JLN countries report more than 60 instances of JLN knowledge product utilization at the national or subnational level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Table of illustrative examples of health system change

| Setting | JLN’s role | Activity | Contribution to outcomes and impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria (JLN, 2021) | Co-developed and applied the JLN Strategic Communications toolkita. | Designed an advocacy plan and lobbied key stakeholders. | Helped to secure the first US $180 million appropriation for the Basic Health Care Provision Fund to provide free primary health care to the poorest and most vulnerable, potentially impacting about 8.6 million Nigerians. |

| Mongolia (JLN, 2021) | Co-developed and applied Empanelment Assessment Toolb. Facilitated support from technical team and from country members expertise. |

Leveraged a World Health Organization-sponsored mobile health technology project focused on home visits to also embed a household-based empanelment approach. | Twenty percent of residents in Arkhangai province were newly assigned a primary healthcare provider. Between 2017 and 2019, Arkhangai reported an increase in preventive screenings of 1.2% at the PHC level and an 8.6% decrease in unnecessary referrals to the provincial-level hospitals. The approach is being scaled up beyond the most geographically isolated target populations and will be rolled out nationally by 2024. |

| Malaysia (JLN, 2021) | Co-developed and applied Medical Audit Toolkitc. Facilitated peer learning from other JLN countries including a study tour to South Korea. |

Supported the establishment of an independent medical audit unit managed by ProtectHealth Corporation (PHCorp) for the flagship PeKa B40 programmed, a federal scheme which covers approximately 520 632 of the poorest and most vulnerable Malaysians and that is being scaled. | The unit reviews about 2000–3000 PeKa B40 claims per month and has followed up on a significant number of cases, including cases of misdiagnosis and incomplete lab or medical histories. PHCorp is also the main purchaser of coronavirus vaccine and uses the audit function to assure integrity of the vaccine rollout. |

Strategic Communication for Universal Health Coverage: Practical Guide, © 2018, Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, Health Finance and Governance Project, Abt Associates, Results for Development.

Empanelment: A Foundational Component of Primary Health Care. Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, Ariadne Labs, and Comagine Health; 2019.

Toolkit for Medical Audit Systems: Practical Guide from Implementers to Implementers, Copyright © 2017, Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, ACCESS Health International.

PekaB40 is a federal programme which provides free health screenings to those from the bottom 40% of beneficiaries.

The JLN’s experience provides insight into factors that contribute to a successful peer-to-peer learning approach. Reflections from over a dozen policymakers from 10 different countries, gained through semi-structured interviews and analysed by inductive thematic analysis, describe the achievements and challenges of the JLN’s peer-to-peer learning approach and the enablers and constraints of peer-to-peer learning, as described below.

Peer-to-peer learning is enabled by the convening power of the JLN, in engaging a network of practitioners with diverse experiences and shared interests and identifying common needs and priorities across these practitioners

It is crucial to engage the right group of policymakers and practitioners. Core to the JLN’s peer-to-peer learning model is curating a network of policymakers who are appropriately positioned to identify their government’s priorities and technical challenges and address them by implementing the knowledge acquired from the JLN. The JLN’s peer-to-peer learning approach relies on multi-stakeholder groups within member countries—CCGs—to identify and convene policymakers and practitioners to JLN technical initiatives. Through the CCG model, the JLN convenes diverse stakeholders within a country to advance technical objectives.

Analysis of the qualitative data showed that the right structure and composition for a CCG varied by country. However, stakeholders commonly noted the importance of representation from all key institutions and policymakers working on UHC. Other characteristics reported to increase the effectiveness of a CCG included establishing a coordinator and central secretariat function, agreeing on the terms of reference for clearly defined roles within the CCG and assigning technical working groups to focus on priority areas. Regular sharing of JLN’s knowledge and products was another common enabling factor across countries that catalysed the successful application of knowledge.

Meaningful peer-to-peer learning requires well facilitated and structured interactions across countries that enable their adaptation to changing circumstances in a timely manner, which is the core strength of JLN

The JLN’s learning model fosters rapid access to cross-country experience sharing. For example, the JLN introduced country pairings, a rapid modality to complement traditional joint learning approaches (Kannan et al., 2023) where experienced technical facilitators convene countries on a topic. Each pairing is composed of a country that enacted a reform of interest, and a country requesting deeper understanding from the resource country. Through a mixed-methods monitoring and evaluation approach, the JLN evaluated its country pairings to distil key points of learning in 2022, conducting three key informant interviews (KII) and administering 24 participant surveys to explore interview findings in greater depth (Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, 2022).

In one such pairing in 2020, Kenya was seeking to establish Primary Care Networks (PCNs) to improve access to quality networked health services and paired with policymakers in Ghana involved in implementing a pilot of a similar service delivery model (Folsom et al., 2023). Through this pairing, Kenya developed guidelines for national implementation of their PCNs and received feedback from the Ghanaian team, enabling a nuanced understanding about how networks would be operationalized (Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, 2022).

Through KIIs, key factors were identified as critical to cross-country learning. Countries needed similar health system applicability, including institutions. Second, the selection of the right group of participants was the key to ensure implementers—such as subnational management or health facility representatives— who were positioned to rapidly apply learning. Additionally, senior officials in the learning communities were able to anticipate and navigate political and institutional challenges to reforms.

Ensuring just-in-time knowledge sharing, which helps countries within their respective windows of opportunity for implementing reforms, is key to successful peer-to-peer learning

This was particularly critical in the rapidly evolving crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The JLN prioritized shorter joint learning experiences which focused on implementing JLN knowledge in real-time, often with in-depth implementation in a single country, with additional JLN countries learning from the ongoing implementation experience. As an illustration of how JLN met the need for new knowledge during the COVID-19 pandemic, the JLN convened South Africa and Malaysia in a facilitated thematic dialogue in 2021. This dialogue aimed at supporting these countries at an opportune moment to learn from each other’s context and plans for involving the private sector for COVID-19 vaccination, has informed the design of modalities for contracting the private sector in both countries.

This approach was applied to the implementation and scale-up of primary care e-consultations in Malaysia. The learning community was designed to foster practical learning by supporting implementation efforts in Malaysia to optimize telephone use for e-consultations to inform policymakers and regulators on the benefits of e-consultations. Experts from six JLN countries and the technical facilitation team helped Malaysia test a hybrid model and standardized e-consultation guidelines in four government-operated primary health clinics (Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, Aceso Global, 2021). In KIIs conducted as part of monitoring and evaluation activities, non-Malaysian members reported that they felt aided in narrowing their feedback and advice on rapidly achievable objectives for the implementing team (Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, Aceso Global, 2021). The Malaysian implementing team agreed, with one member explaining:

‘With the community of practice, the meaningful thing is that we’ve created proper documentation for telehealth. We have done telehealth before being involved in the JLN, but we were doing it in pieces. Now that there’s a standardised method and the guidelines are documented, it’s easier for providers to use the guide when doing telehealth… With the community of practice, there’s a structure, it’s a weekly thing; we come up with the guideline faster and with proper discussion….’

This approach resulted in a health system change: all client respondents were satisfied with the service (n = 598). The implementation team synergized and supported Malaysia’s eHealth app, MySejahtera, by developing short videos on breathing exercises and using a pulse oximeter which garnered 13 038 115 views (Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, Aceso Global, 2021).

A key constraint for the network, however, is managing the transition of country champions. Well-performing CCGs can change course when key actors shift to other roles. It is therefore critical to regularly solicit feedback from CCG leadership and engage CCG members in JLN programming to cultivate in-country champions of the joint-learning approach and to anticipate and manage member transitions. Language barriers are another ongoing challenge. Though most JLN events and products are in English, the JLN is increasingly using live interpretation during meetings, and where resources are available, translating key knowledge products into multiple languages.

Across all qualitative data collection experiences, positive feedback about the JLN structure outweighed concerns; a resultant limitation was that there was no focus on exploring replacement of the JLN structure with something else.

Conclusion

This paper offers reflections on factors which are supportive of experience-based knowledge exchange between practitioners from diverse settings within the context of global efforts to achieve UHC, in a country-led manner and provides insight to how future efforts could be improved. Successful peer-to-peer learning relies on investment in intentional, sustained and structured engagement with country practitioners, and the ability to react to learning needs in a flexible and timely manner. Reflection on the JLN’s peer-to-peer learning model suggests that this modality facilitates in-country convening of key stakeholders, knowledge sharing across countries and implementation-oriented practical learning, in a timely manner amidst rapidly evolving programmes. Future documentation and research by the JLN and other networks and initiatives promoting peer-to-peer learning—such as case studies or innovative monitoring and evaluation efforts to retrospectively identify examples of changes in relationships, policies and practices and to determine if peer-learning contributed to changes—are needed to understand and refine peer-learning modalities in an international context.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the technical teams of the JLN collaboratives for their efforts in capturing evidence of impact: Aceso Global (Gerard La Forgia, Jonty Roland, Rob Janett, Jake Mendales, Madeleine Lambert and Esteban Bermude), R4D (Cheryl Cashin, Agnes Munyua, Henok Yemane and Nivetha Kannan), Meghan Guida (Independent consultant) and JLN country members who participated in the key informant interviews cited in this report. We are also grateful for the leadership in implementing Monitoring and Evaluation efforts across initiatives of the JLN by Management Sciences for Health (Maeve Conlin, Kamiar Khajavi and Sara Wilhelmsen). Finally, we are immensely grateful to JLN participants across all member countries who are the substance of the JLN: to those who have served in the JLN’s CCGs and steering group and every participant who has been a part of JLN learning communities over the past decade. The authors would also like to thank Anas Ismail and Lorena Guerrero-Torres from the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO for their help with proofreading the paper.

Contributor Information

Lauren Oliveira Hashiguchi, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA.

Maeve Conlin, Management Sciences for Health, 4301 Fairfax Drive, Suite 400, Arlington, VA 22203, USA.

Dawn Roberts, Independent Consultant, Portland, ME, USA.

Kathleen McGee, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA.

Robert Marten, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization, Avenue Appia 20, Geneva 1211, Switzerland.

Stefan Nachuk, Morris Brothers LLC, Kuala Lumpur, Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Ali Ghufron Mukti, BPJS Kesehatan (Social Insurance Administration Organization), Government of Indonesia, JL Letjen Suprapto Cempaka Putih, Jakarta 10510, Indonesia.

Aditi Nigam, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA.

Naina Ahluwalia, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA.

Somil Nagpal, The World Bank, 12th Floor, IDX Building, Tower 2, Sudirman CBD, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Abbreviations

CCG = Country Core Group

JLN = Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage

PHCorp = ProtectHealth Corporation (Malaysia)

SG = Steering Group (refers to the JLN Steering Group)

UHC = Universal Health Coverage

Funding statement

There was no funding received specifically for this paper. This work was supported by respective organizations to which the individual authors are affiliated, to the extent that their time was covered by their employers, where applicable.

Author contribution statement

Conception or design of the work: S.N., L.O.H., K.G.

Data collection: M.C., D.R.

Data analysis and interpretation: M.C., D.R.

Drafting the article: L.O.H.

Critical revision of the article: L.O.H., K.McG., A.G.M., R.M., S.N., A.N., N.A., S.N.

Final approval of the version to be submitted: L.O.H., M.C., D.R., K.M., A.G.M., R.M., S.N., A.N., N.A., S.N.

L.O.H., K.M. and S.o.N. contributed to the overall framing of this work. D.R. and M.C. were responsible for the collection, analysis and interpretation of monitoring and evaluation data and JLN member feedback cited in this work. L.O.H was responsible for draft manuscript preparation, with all authors contributing throughout the writing process. All authors provided critical revision of the article and approved this final submitted version.

Reflexivity Statement

The author team for this submission is consciously well balanced by gender, seniority and regional location. Six of the co-authors are women, at least two are based in LMICs and at least three authors are citizens of LMICs. The co-authors include a wide diversity of seniority by position and years of experience, ranging from several team members with under ten years of professional experience to those with over thirty years of experience, including the President Director of a large social security organization.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this paper was not required by our institute.

Conflict of interest statement

RM is a staff member of the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO. He is alone responsible for the views expressed in this article, which do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the World Health Organization.

References

- Asamani JA, Nabyonga-Orem J. 2020. Knowledge translation in Africa: are the structures in place? Implementation Science Communications 1: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkisson A. 2015. Stakeholder Partnerships in the Post-2015 Development Era: Sharing Knowledge and Expertise to Support the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. New York, USA: UN Department for Social and Economic Affairs.

- Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Green LW. 2018. Building capacity for evidence-based public health: reconciling the pulls of practice and the push of research. Annual Review of Public Health 39: 27–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashin C (ed). 2015. Assessing Health Provider Payment Systems: A Practical Guide for Countries Working Toward Universal Health Coverage. Washington, DC, USA: The Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage.

- Folsom A, Kinter A, Satzger E et al. 2023. Primary Health Care Performance Initiative in collaboration with the Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage. Transforming PHC Delivery and Financing through Primary Care Networks. Washington, DC, USA. https://www.improvingphc.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/phcpi_community_of_practice_learning_brief_english.pdf.

- Gadsden T, Ford B, Angell B et al. 2022. Health financing policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the first stages in the WHO South-East Asia Region. Health Policy and Planning 37: 1317–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage. 2021. Case Study: Using Strategic Communications in Nigeria Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage.

- Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage. 2021. Case Study: Medical Audit in Malaysia. Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage.

- Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage. 2021. Case Study: Person-Centered Integrated Care in Mongolia. Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage.

- Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage . 2022. Management Sciences for Health, Results for Development. Primary Health Care Financing and Payment Country Pairing Evaluation Report. Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, Aceso Global . 2021. JLN Community of Practice on Scaling E-Consultations Patient Pathways and Pandemics: Covid-19 and Beyond Learning Exchange Evaluation Report. Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage.

- Juckett LA, Bunger AC, McNett MM et al. 2022. Leveraging academic initiatives to advance implementation practice: a scoping review of capacity building interventions. Implementation Science 17: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan N, Munyua A, Yemane H. Country Pairings: A new collaborative learning modality deepening engagement with country practitioners. https://www.jointlearningnetwork.org/news/country-pairings-a-new-collaborative-learning-modality-deepening-engagement-with-country-practitioners/, accessed 1 February 2023.

- Khan MS, Meghani A, Liverani M et al. 2018. How do external donors influence national health policy processes? Experiences of domestic policy actors in Cambodia and Pakistan. Health Policy and Planning 33: 215–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagomarsino G, Garabrant A, Adyas A et al. 2012. Moving towards universal health coverage: Health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. The Lancet 380: 933–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester L, Haby MM, Chapman E et al. 2020. Evaluation of the performance and achievements of the WHO Evidence-informed Policy Network (EVIPNet) Europe. Health Research Policy and Systems 18: 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla C, Herrera CA, Basagoitia A et al. 2017. The Evidence-Informed Policy Network (EVIPNet) in Chile: Lessons learned from a year of coordinated efforts. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 41: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukti AG. 2023. Kompas BPJS, Siapa Paling Diuntungkan? (BPJS, Who Benefits the Most?) https://www.kompas.id/baca/english/2023/01/27/bpjs-who-benefits-the-most.

- Nachuk S, Martínez Valle A, Nagpal S. 2021. A Decade of the Joint Learning Network: A Vision Realized: World Bank Blogs https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/decade-joint-learning-network-vision-realized, accessed 1 February 2023.

- Özaltın A, Cashin C eds. 2014. Costing of Health Services for Provider Payment: A Practical Manual Based on Country Costing Challenges, Trade-Offs, and Solutions. Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage.

- Schneider H, Zulu JM, Mathias K et al. 2019. The governance of local health systems in the era of Sustainable Development Goals: Reflections on collaborative action to address complex health needs in four country contexts. BMJ Glob Heal 4: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff ZC, Sparkes S, Skarphedinsdottir M et al. 2022. Rethinking external assistance for health. Health Policy and Planning 37: 932–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon A, Bloom D, Oliveira Hashiguchi L et al. eds. 2021. Making the Case for Health: A Messaging Guide for Domestic Resource Mobilization. Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage. [Google Scholar]

- Voller S, Schellenberg J, Chi P et al. 2022. What makes working together work? A scoping review of the guidance on North-South research partnerships. Health Policy and Planning 37: 523–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson G. 2007. Knowledge, innovation and re-inventing technical assistance for development. Progress in Development Studies 3: 183–99. [Google Scholar]