Abstract

High human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–prevalence countries in Southern and Eastern Africa continue to receive substantial external assistance (EA) for HIV programming, yet countries are at risk of transitioning out of HIV aid without achieving epidemic control. We sought to address two questions: (1) to what extent has HIV EA in the region been programmed and delivered in a way that supports long-term sustainability and (2) how should development agencies change operational approaches to support long-term, sustainable HIV control? We conducted 20 semi-structured key informant interviews with global and country-level respondents coupled with an analysis of Global Fund budget data for Malawi, Uganda, and Zambia (from 2017 until the present). We assessed EA practice along six dimensions of sustainability, namely financial, epidemiological, programmatic, rights-based, structural and political sustainability. Our respondents described HIV systems’ vulnerability to donor departure, as well as how development partner priorities and practices have created challenges to promoting long-term HIV control. The challenges exacerbated by EA patterns include an emphasis on treatment over prevention, limiting effects on new infection rates; resistance to service integration driven in part by ‘winners’ under current EA patterns and challenges in ensuring coverage for marginalized populations; persistent structural barriers to effectively serving key populations and limited capacity among organizations best positioned to respond to community needs; and the need for advocacy given the erosion of political commitment by the long-term and substantive nature of HIV EA. Our recommendations include developing a robust investment case for primary prevention, providing operational support for integration processes, investing in local organizations and addressing issues of political will. While strategies must be locally crafted, our paper provides initial suggestions for how EA partners could change operational approaches to support long-term HIV control and the achievement of universal health coverage.

Keywords: External assistance for health, development assistance for health, transition, sustainability, HIV control, HIV/AIDS, health systems

Key messages.

Rethinking external assistance (EA) for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) to align with current realities is critical to achieving long-term, sustainable HIV control and universal health coverage.

The nature and scope of EA have exacerbated challenges in sustaining HIV programming, such as limited financial space, a lack of focus on the prevention of new infections, barriers and resistance to integration of HIV services into health systems, limited capacity and authority among local organizations and eroding political will.

EA partners in the fight against HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome need to develop a primary prevention agenda, support operational processes to facilitate integration, invest in local institutional capacity and work to address issues of political will among diverse stakeholders.

BACKGROUND

Writing in 1990, Chin and Mann identified a foremost challenge for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention and control to be ‘ensuring sustained and sustainable National AIDS programs’ (Chin and Mann, 1990). They observed that this would entail strengthening health systems so that HIV services could be better integrated, sustaining coordinated activity across diverse and frequently fragmented stakeholders, maintaining social and political commitment to address the pandemic in the face of multiple other demands on government and, in particular, ensuring commitment to marginalized groups who frequently face discriminatory attitudes and policies (Chin and Mann, 1990). This theme of sustainability has been present over the decades since this paper was published. For example, the 2008 President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) reauthorization (the Lantos and Hyde Act) repeatedly emphasized the need for sustainability and capacity building of local organizations ‘through the support of country-driven efforts’ and ‘the inclusion of transition strategies’ (Lantos and Henry, 2008). The WHO’s (2016) strategy ‘Towards ending AIDS’ focused efforts on reducing new infections and enhancing access to HIV services as part of universal health coverage (WHO, 2016). Nonetheless, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) targets to end the epidemic focus heavily on treatment, with the 95-95-95 targets1 being the most commonly cited and understood definition of HIV control.

HIV exceptionalism, meaning the tendency to treat HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) differently from other infectious diseases in terms of policies, laws and services, has always been contentious, garnering both strong support and opposition (Cock and Johnson, 1998; Benton and Sangaramoorthy, 2021). From the start of the epidemic, donor-led HIV programmes in high-prevalence countries have often established separate financial channels, supply systems and service delivery points in a bid to achieve high coverage targets. These parallel systems fragment the health system and create inefficiencies, thus making it harder to achieve sustainability. While in recent years there have been efforts to promote greater integration driven by national health strategies in low- and middle-income countries—as well as critiques of external assistance (EA) structures more generally (Moyo, 2009; Melesse, 2021)—these have often been met with resistance, particularly from those stakeholders who have benefitted from existing patterns of resource allocation (Benton and Sangaramoorthy, 2021).

Countries in Eastern and Southern Africa that currently experience high HIV prevalence continue to receive substantial EA for HIV programming and lack a clear pathway to sustainability (Kates et al., 2020). Global trends have shown that domestic resources have steadily increased over the period 2000–15 as EA (estimated at USD7.8 billion in 2019 (Kates et al., 2020)) has declined (Dieleman et al., 2018). Still, recent analyses from the Global Burden of Disease Health Financing Collaborator Network show an uneven financing picture, with stark differences in EA dependence across regions, income and HIV prevalence strata (Dieleman et al., 2018). In sub-Saharan Africa, EA accounts for almost two-thirds (63.9%) of HIV/AIDS spending (Dieleman et al., 2018).

UNAIDS estimates that ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 would require $29 billion annually across domestic, bilateral and multilateral channels (UNAIDS, 2021). However, it seems likely that with building concern around the emergence of new infectious diseases (such as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)) as well as priorities in other domains, including climate change, it will prove very difficult to sustain EA for HIV/AIDS at historic levels. Governments, meanwhile, are managing competing multisector priorities in a context of increased donor transition, economic slowdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic (Silverman, 2018; African Union, 2020; Anyanwu and Salami, 2021) and other global challenges. Countries are thus at a risk of greatly reduced EA for HIV before reaching epidemic control.

Prior countries have managed the transition away from HIV funding with mixed success (Jerve and Jerve, 2008; Vogus and Graff, 2015; Flanagan et al., 2018; Zakumumpa et al., 2021a; Huffstetler et al., 2022). These transition examples, largely in middle-income countries, have provided early learnings around enabling factors for transition, highlighting the importance of strong political will and social contracting for civil society organizations and suggesting best practices for managing transition processes, including robust pre-transition activities, phased transition approaches and engaging subnational actors in the transition process (Bennett et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2015; Flanagan et al., 2018; Paina et al., 2023). Donor agencies, however, have neither sufficiently responded to these learnings nor explored how similar dynamics may play out in low-income, high-burden settings, such as those across Eastern and Southern Africa. As Shroff et al. acknowledge, EA partners continue to frame transition around external targets for specific health programmes and limit systems-oriented investments to address sustainability needs beyond co-financing (Shroff et al., 2022).

The concept of sustainability is not straightforward and has been defined in many ways (Gruen et al., 2008; Moore and Roux, 2011; Scheirer and Dearing, 2011; Global Fund, 2021; Okere et al., 2021). Here, we understand sustainability to mean programming that maintains HIV control at scale through a package of HIV prevention and treatment interventions and strategies that rely predominantly on domestic resources and institutions. Accordingly, our notion of HIV programme sustainability does not necessarily indicate the end of aid for HIV, but rather a likely reappraisal of levels of aid, and a shift in strategy to address the underlying mechanisms that enable sustainability. In consideration of this changing role of EA, our paper seeks to address two objectives. First, in the Results, we unpack stakeholder perspectives on the extent to which HIV EA in the region has been programmed and delivered in a way that supports long-term sustainability. Second, drawing on respondent perspectives, in the Discussion, we explore how development agencies could change operational approaches to support long-term, sustainable HIV control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used a mixed methods design to address our research aims. We first conducted key informant interviews (KIIs) with stakeholders actively involved in HIV planning and implementation throughout Southern and Eastern Africa. We then paired this with a quantitative analysis of Global Fund grant allocations from 2017 until the present in three countries: Malawi, Uganda, and Zambia. In this exploratory design, the qualitative methods were emphasized to explore dimensions of sustainability (Cresswell, 2017); the quantitative inquiry was subsequently designed to illustrate the picture ahead along themes identified in the qualitative analysis.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

Three authors conducted 20 semi-structured KIIs with respondents from government, civil society, development partners, implementing organizations and academia/research (at both country and global levels) to understand diverse perspectives on long-term HIV control and EA (Table 1). Respondents were purposively sampled to ensure a breadth of regional perspectives and drew on their experience working in HIV control across sub-Saharan Africa (including Botswana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia). While we endeavoured to categorize respondents, it is worth noting that many hold—or have held—multiple institutional affiliations and have regional experience; in some cases, the respondent’s home institution is not based in their country of residence. The KII guide explored factors contributing to sustainable HIV control as well as specific issues of service integration, services for key populations (KPs), government priorities and how COVID-19 had impacted expectations for HIV service delivery. Interviews were conducted in English on Zoom in 2021, recorded and transcribed. Throughout the data collection process, interviewers met regularly to debrief on emergent themes.

Table 1.

Key informant demographics

| Number of respondents (male) | Number of respondents (female) | Number of respondents (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Africa | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Southern Africa | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Global level | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| Total | 11 | 9 | 20 |

| Government | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Civil society | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Academia/research | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Development partners | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Implementing organizations | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 12 | 8 | 20 |

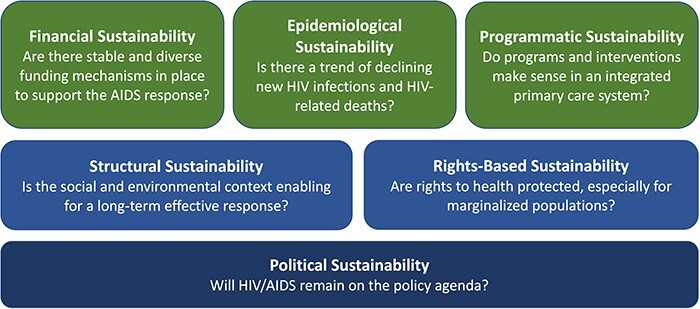

For analysis, we used an existing conceptual framework by Oberth and Whiteside (2016), which identifies six central and interdependent tenets of sustainability (Figure 1), to develop an initial codebook, including code definitions and appropriate applications of each code within the study context (Oberth and Whiteside, 2016). The initial codes reflected the six dimensions of sustainability identified by Oberth and Whiteside, e.g. financial, epidemiological, programmatic, structural, rights-based and political sustainability (Oberth and Whiteside, 2016). The codebook was then refined by two authors and additional codes included to account for health system and governance issues that cut across domains, as well as respondent perspectives on how the organization and practice of EA have contributed to sustainability in the region. Data were deductively coded by the first author in MaxQDA, and the findings were synthesized. The initial findings were then shared with co-authors for discussion, feedback and refinement over multiple rounds. Recommendations were developed collectively by the co-authors in light of the research findings.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for sustainability in HIV programmes (Adapted from Oberth and Whiteside, 2016)

Quantitative data collection and analysis

The quantitative analysis was used to explore key themes that emerged from the qualitative KIIs. We analysed budget data from grants in three countries—Malawi, Uganda and Zambia—purposively selected for the analysis as typical cases for the region and given sufficient author familiarity with the HIV landscape in each country to interpret the data and data availability. None of these countries are on an accelerated timeline for transition, given their low-income, high-HIV burden status; however, the Global Fund (2023a) strongly encourages transition planning at least a decade in advance. We constructed the dataset by extracting publicly available data from the Data Explorer, which captures funding from the Global Fund but does not reflect all HIV-related EA. HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and Resilient and Sustainable Systems for Health (RSSH) grants from 2017 onwards were included in the analysis. We excluded grants prior to 2017 to account for any programmatic changes that may have resulted from the Global Fund Sustainability, Transition and Co-financing Policy agreed in 2016 (Global Fund, 2016). TB grants and multi-country grants that included our sampled countries were excluded from the analysis. Six total grants were included (two in Uganda, three in Malawi and one in Zambia).

Each grant module was categorized into one of the eight categories: (1) prevention, (2) treatment, (3) RSSH, (4) Key Populations (KP), (5) COVID-19, (6) testing, (7) programme management, and (8) others. The total USD budgeted and proportions were calculated in each category. The categorization of modules was collectively reviewed and agreed upon by the analytical team.

Protocol and tools for the KIIs were reviewed by institutional review board and deemed non-human subject research.

RESULTS

We present the results according to each of the sustainability domains from Figure 1. Quantitative estimates of Global Fund investments are presented in relevant sustainability domains.

Financial sustainability—are there stable and diverse funding mechanisms in place?

KII respondents were conscious of countries’ heavy dependence on EA and described the very real challenges in pushing governments to increase financing for HIV/AIDS where fiscal space is limited. As one advocate described,

As civil society we try to do our best, to start pushing our governments to ensure they start taking ownership of some of these programs. And that they are putting in more resources. But sometimes there is an extent or limit which you can push your government. Sometimes the fiscal space is just not right. It cannot allow them to pump more resources. There is only so much that they can provide. (Country level, Eastern Africa, civil society)

Per respondents, the nature of EA investments has also impacted the overall financing stability. While governments have contributed significant resources for antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, e.g. development partners have taken on large, recurrent costs like human resources for health that are difficult for governments to absorb. This was seen as an acute risk to sustainability.

So, the ministry of health provides the ARVs themselves. I think the bulk of them. But in terms of human resources for health and other activity costs, which is the bulk of the budget, those are being led by donors through NGOs…And when you’re thinking of trying to achieve some level of sustainability and transition, I think then that will be exposed, and we will risk losing some of the progress that has been made. (Country level, Southern Africa, implementing partner)

The government doesn’t have the money to pay all the health workers that they need to have and in fact…the IMF stops them from recruiting more personnel. (Global level, implementing partner)

Furthermore, respondents reflected that despite a professed ‘localization agenda,’ development partners have continued to control where money is channelled and how it is spent. Global and country-level respondents alike indicated a development partner preference to work through international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), either because they feared inefficient financial management within governments or because they felt that local NGOs did not have sufficient systems and management capacity. Global actors admitted that this practice also reflected organizations’ own incentives to retain funding:

We have gone to great lengths to make sure that the government under the narrative of corruption…cannot receive direct funds and they do not. I had to almost get a Supreme Court ruling to give funds directly to [a country government] for a project that we had total visibility in, in terms of what happened to the money, etcetera. And it’s because the culture we’re in does not want to give that up because they understand its connection to their continued funding. (Global level, academia/research)

This concentration of financial resources within international NGOs has limited the diversity of financing mechanisms and, per respondents, contributed to deferred capacity development for financial management within local institutions.

Epidemiological sustainability—is there a trend of declining new HIV infections and HIV-related deaths?

Many respondents felt the HIV treatment agenda has been successful, with strong support from PEPFAR and the Global Fund. Emphasis on treatment, however, has shaped the conceptualization of HIV control to have a focus on treatment targets (e.g. 95/95/95), rather than reducing HIV incidence and documenting patient outcomes. Across the board, respondents reported that the prevention agenda had been neglected and underfunded. This bore out in our quantitative analysis as well. Across the three countries, ∼57.98% of USD budgeted from the Global Fund was in treatment-related modules compared with 7.57% of investments budgeted for prevention. Investments for treatment ranged from 40% in Zambia to 74% in Malawi, compared with 7% for prevention in Malawi and Uganda, to 9% in Zambia. Table 2 presents the total USD budgeted by category, across the countries.

Table 2.

Global Fund USD Budgeted by theme and country (from 2017 till to date)

| Total | Uganda | Zambia | Malawi | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | USD | % | USD | % | USD | % | USD | % |

| Prevention | 168 161 582 | 8 | 57 126 369 | 7 | 53 272 548 | 9 | 57 762 665 | 7 |

| Treatment | 1 288 859 033 | 58 | 442 493 970 | 54 | 229 906 930 | 40 | 616 458 133 | 74 |

| RSSH | 123 843 834 | 6 | 9 116 381 | 1 | 55 138 917 | 10 | 59 588 536 | 7 |

| KPs | 27 052 932 | 1 | 16 355 462 | 2 | 772 431 | <1 | 9 925 039 | 1 |

| COVID-19 | 345 673 728 | 16 | 219 541 904 | 27 | 125 708 782 | 22 | 423 042 | <1 |

| Testing | 97 501 466 | 4 | 45 126 904 | 6 | 14 400 420 | 3 | 37 974 142 | 5 |

| Programme management | 59 781 323 | 3 | 3 324 500 | <1 | 36 342 038 | 6 | 20 114 785 | 2 |

| Other | 111 940 249 | 5 | 23 297 085 | 3 | 59 839 673 | 10 | 28 803 491 | 3 |

| Total | 2 222 814 147 | 100 | 816 382 575 | 100 | 575 381 739 | 100 | 831 049 833 | 100 |

Within the prevention space, activities have centred on biomedical approaches to prevention, such as microbicides, medical male circumcision and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), as opposed to primary prevention activities focused on reducing the ‘pipeline of infection’. Respondents expressed concern that, on its own, PrEP as a prevention strategy would be insufficient to achieve long-term control.

At the current levels of PrEP and the current levels of antiretroviral treatment, coverage, and viral suppression, and the current levels of other things that are in the toolbox it’s not going to get us to control, and they are certainly not going to keep us there…And funding from ART [antiretroviral therapy], from everything I have seen, funding has stagnated. It is not going up anymore. (Global level, civil society)

However, respondents recognized that the investment case for primary prevention was not as straightforward as the case for treatment or biomedical prevention activities. One respondent described how this played out to affect agenda-setting in the region:

We have zero understanding [of] what returns we’re getting [on primary prevention] …but here is the treatment…and the treatment as a prevention approach. There was this ideological struggle, and treatment or treatment prevention won the battle…Primary prevention obviously got side-lined in these discussions, and obviously was a harder thing to do. Because with the primary prevention you also needed some political leverage over the national government or their criminalizing laws, some societal structural barriers, and numerous other things. So, probably a large part of the constituency felt more comfortable taking this as a good strategy on going forward as opposed to fighting the battle for primary prevention… (Global level, civil society)

To some extent, the treatment focus also reflects the priorities of local advocacy groups who, understanding the significant structural barriers at-risk populations face, and embracing those living with HIV, have delivered a message of ‘staying well’ more strongly than a message of prevention.

Still, sustaining long-term HIV control will require a hastened decline in new HIV infections, and this may prove difficult in an environment where prevention is deprioritized. It is expected that prevention may get crowded out as a priority in transition planning, given the high costs and perceived importance of retaining people already on treatment.

During the transition, the priority of trying to keep those already in treatment to continue tend to shoot very high up, partly because there is…a big population that is in care. There are also providers who are already with sunk costs in this area of trying to continue to provide the services. And there is big voice by those agencies that have come up to try and really speak for these benefits…so there are very few that can speak to the prevention side of things in terms of the power and policy reforms. (Country level, Eastern Africa, academia/research)

Programmatic sustainability—do programme and interventions make sense in an integrated primary care system?

There was a consensus among respondents that moving towards integration was a necessary—and substantial—pivot within the HIV space. Respondents observed, however, that what is meant by integration varied enormously. For some, the future state was a fully integrated primary care system inclusive of HIV/AIDS care; others described selective integration with sexual and reproductive services or non-communicable disease management. Still others sought integration within sub-systems of the health system, i.e. information and supply chain.

The debates around integration reflected different views of what would be feasible following decades of parallelism and structures that are not set up to manage or prioritize health systems investments. Within global coordinating bodies, respondents described how stakeholders brought significant disease expertise but lacked expertise in building strong, resilient health systems. At the country level, structures also reflected a vertical disease orientation.

There are still countries which have a separate system for HIV, a separate system for malaria. There are plenty of cases of a donor dependency, that has created over the course of the past several decades…these empires that kind of stand on their own and does not allow the power base of those on top of those empires to release their powers. (Global level, civil society)

Financially, RSSH investments accounted for 6% of Global Fund’s budgeted funds across Malawi, Uganda and Zambia, covering primarily infrastructure/equipment, human resources for health and external professional services, communications materials and travel costs; as noted in internal reports, RSSH investments are challenging to design, deploy and track within existing organizational structures (Office of the General Inspector, 2019).

Respondents reflected honestly about the role of EA in driving HIV exceptionalism, as well as development partners’ resistance to change, driven by concerns around losing control within their own funding streams or losing the ability to monitor their in-country investments.

The last five to seven years [UN organizations] are literally not interested in integration…In the past they were keen but now they are definitely not. Even internally they themselves have big quarrels…when they should be working with the same system. So, you know you’ve taken my mandate out, why are you doing that one belongs to [me]…there’s a lot of sometimes I call it “agency fights”. (Country level, Eastern Africa, academia/research)

The PEPFAR program loves to keep control over things. There’s a lot of other things that we can do to integrate in, particularly the oversight in management of HIV services is a government’s responsibility. (Global level, development partner)

These political negotiations take place at the country level as well, both within government agencies (e.g. agency ‘turf wars’) and among healthcare providers whose expectations about benefits have been shaped by historically parallel—and higher paying—systems.

It’s all about that turf. The turf within the ministries and who’s in charge and is this a partner organization coming in to try and to take some of our scope. So, you have to be able to know the inside politics and how to navigate them. (Country level, Southern Africa, academia/research)

We are currently trying to transition services and the main problem that we have is when we are now expecting the ministries, nurses to do this procedure, they expect to be paid something beyond their normal salary. Even if they’re doing this within the normal eight-hour shift, that’s expected. So that mindset is right at the grass root of service provider. And I think it permeates… it goes right up to the top, to even the district managers, the policy makers. [They] are still of the impression that these tasks are supposed be done by someone else or paid for by someone. (Country level, Southern Africa, implementing organization)

Country-level respondents were also acutely aware of the logistical barriers to reorganizing service delivery for integration, describing the need to articulate the approaches, policies and systems that would enable integration while keeping people at the centre. Just as parallelism was driven by EA, global and country respondents alike saw a role, and perhaps a responsibility, for development partners in facilitating integration and expanding capacity to deliver key functions.

Multilateral organizations that have been primary implementers need to shift to capacity expanding strategies…Stuff [e.g., overseeing clinics, setting up surveillance and information systems, reviewing data] that is now quite easily done is not done and you’ve got to ask yourself why haven’t you shared that with your colleagues and country? (Global level, civil society)

The other issue I think has been how to negotiate with the partners that come on board to help government…negotiate how the partners can actually complement what is already on the ground (Country level, Eastern Africa, academia/research)

Rights-based sustainability—are rights to health protected, especially for marginalized populations?

One of the thorniest issues challenging transition and sustainability is how to ensure service continuity to marginalized—and sometimes criminalized—populations such as people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, sex workers and women and girls. While EA for rights-based sustainability has been relatively limited (Table 1 indicates that in terms of Global Fund support, <2% of HIV, TB/HIV and RSSH grants are budgeted in modules targeting KPs), in many instances, donors, development partners and international NGOs have been a counterweight to national governments’ resistance to serving stigmatized populations and have pushed to reduce barriers to care, sometimes filling gaps left by government programmes.

A major concern among respondents was how to move towards a more integrated system while also maintaining safe, stable services for vulnerable populations. Respondents had disparate views on what might be possible, with some optimistic about the possibility of integrating KPs into regular services, and others concerned about the ramifications for protecting vulnerable populations. Regardless, respondents shared a view that EA had supported the right to health and that continuing to do so within countries by addressing both legal/policy changes and structural barriers was critical.

I think we also have strategies…whereby we are going to work with the parliamentarians, make sure that the issues of law, the laws are amended, but also, the issues of stigma… of changing the laws has also been presented to our human rights commission, which is a board that is appointed by government, but it has a lot of power in terms of pushing for laws. We already know the challenges that we are trying to work on them. (Country level, Eastern Africa, government)

Respondents also reflected that channelling government funds to local NGOs to provide KP-oriented services—one strategy for replacing EA funding to NGOs working directly with KPs—will not be workable in many contexts.

Right now, most of what the world thinks about in terms of sustainability is some type of social contracting mechanism, that somehow magically the governments are going to start to hire all the same people, contract with all the same people that we use to execute the program. I just think that that’s wishful thinking and when it gets to KP [key populations], it’s almost… Again, these are organizations that officially should not exist, or they would wish did not exist. (Global level, development partner)

Structural sustainability—is the social and environmental context enabling for a long-term effective response?

Stronger strategies to address the underlying risk factors and barriers to care were frequently identified by respondents as an area of need. Informants described a responsive system as one that understands and addresses the complex structural determinants of HIV. However, this is challenging in an environment that favours biomedical solutions and given difficulties linking investments in structural barriers to change in HIV outcomes. These issues underline the challenges emerging from deprioritizing the contextual demands of primary prevention raised earlier, including sustaining support for root cause interventions.

Still, respondents were clear that achieving long-term HIV control was predicated on addressing structural barriers, particularly gender-related barriers to health.

It is almost impossible to imagine dealing with HIV without dealing with gender-based violence… I think it is a kind of deeply structural set of issues and I am not sure how one gets one’s head around that. (Country level, Southern Africa, academia/research)

The main barrier from the community perspective and individual perspective is the socioeconomic challenges that people face which make them vulnerable to HIV, especially woman and especially young girls. We are still very far away from reaching a solution. (Global level, implementing organization)

Nearly all respondents expressed a need for targeted investment among women and girls to accelerate HIV control. Respondents also emphasized that tackling the root causes of HIV would require a stronger community orientation, including improved community health centres and community-based monitoring and, importantly, increased governance capacity within community-based organizations.

Community-based [organizations] they have the expertise, and they have the know-how…but how do we make sure [they have] the right tools to collect data? How do we store our data? How do we make sure we have the right financial systems in place? How do we make sure we can hire an accountant who is professional, who is qualified or an HR? (Country level, Global level, civil society)

Community monitoring right now is a big push, and I think that is really important. If I was a donor and I was going to be thinking about scaling back my investment or my presence I would want to make sure, in addition to a strong relationship with the government, that there was a strong, vibrant community, civil society that was empowered to be a watchdog and to play an important role from outside the government in trying to ensure that services, that the goals that were agreed upon that also are what within global standards and are needed to achieve control when followed. (Global level, civil society)

Nobody wants to fund [capacity building for local organizations] and therefore our local organizations end up being around for a short period of time and in the end, they get swallowed up by something else, who[se agenda] are easily influenced by whatever funding stream is available. (Country level, Southern Africa, academia/research)

Political sustainability—will HIV remain on the policy agenda?

Political sustainability underlies many of the emerging issues raised by respondents across the sustainability tenets, such as difficulty in generating political will to tackle HIV prevention or how to address the epidemic among marginalized populations. Respondents explained that at this point in the fight against HIV, the challenges have become largely political in nature.

How do you get Governments to put more money to sustaining the epidemic?…Even Governments who are capable of financing their own response… you will not find [them] interested in financing key population programs…yet we know it is the pillar for sustaining the kind of work that needs to keep the epidemic quite sustained at a very low level. Now, really, the constraints are really political [in] nature. (Country level, Eastern Africa, development partner)

But first of all, [change requires] real political commitment because when I say political commitment…We are not only talking about putting the money, embarking behind the program. We are not only talking about supporting the programs. We’re probably talking about societal engineering, because, unless we change some attitudes towards some population groups which seem to be driving the epidemic in most parts of the world…[it] require[s] structural changes in the legislation, as well as changing most importantly societal attitudes. (Global level, civil society)

The history of HIV exceptionalism, respondents reflected, has also created an environment in the Southern and Eastern Africa regions in which countries rely on, and often expect, external organizations to oversee HIV activities. This means that governments are less directly accountable for HIV outcomes and can feel diminished ownership over programming. This can directly affect domestic resource mobilization, as governments, expecting EA to persist, do not increase funding for health or reallocate HIV funding towards other priorities within or outside the health sector. Respondents understood the very real challenges in jockeying for political space for HIV for government staff who have long priority lists and limited resources, but some also felt there was a need for a drastic rethinking of the most appropriate role for EA to play in driving the policy agenda.

We need to stop lying to ourselves about what our role is when we’re trying to do healthcare in someone else’s country. Who’s charged with that responsibility? The population charges their political system, their government, to do it.” (Global level, academia/research)

As health priorities (and political climates) shift, these issues of political sustainability—both maintaining political will and developing the necessary governance architecture—are central to ensuring the sustainability of HIV outcomes, even as programmes evolve.

DISCUSSION

EA for HIV/AIDS has undoubtedly had a significant impact in reducing HIV morbidity and mortality (Global Fund, 2022), but, as our analysis highlighted, EA practices have also created interconnected challenges to promoting sustained HIV control. Low-income countries’ limited fiscal space and focus on ARV spending make it particularly difficult to expand budgets as well as absorb EA-supported health systems investments, like human resources. These fiscal realities coupled with a localization agenda that does not fully leverage local NGOs who are well positioned for service delivery negatively impact ‘financial sustainability’. ‘Epidemiological sustainability’ is undermined by missing investments in prevention, especially primary prevention; at the same time, while ‘programmatic sustainability’ requires integration with broader health systems, the path forward is unclear and may face some resistance among global and local stakeholders. Both epidemiological and programmatic sustainability are influenced by a development industry that benefits from vertical, treatment-focused investments. ‘Rights-based and structural sustainability’ are critical for HIV control yet deeply complex to address across country income levels: services for KPs cannot be successful or well integrated without addressing government resistance and outright criminalization of practices by many KPs, while, at the same time, structural determinants of HIV require changes to social norms that make young girls, women and KPs vulnerable. Underlying all these dynamics is low political will within some governments to address structural determinants and prevention needs, reflecting weak ‘political sustainability’. Each of these domains is, of course, interconnected—sociopolitical issues may diminish the political will to address HIV among stigmatized populations, e.g. and ultimately limit the financial sustainability of services targeted to those groups; limited investment in primary prevention over time may have also contributed to rising infections among women and girls, challenging structural sustainability in many contexts.

These findings reflect similar dynamics identified in sub-Saharan Africa and other regions (Vogus and Graff, 2015; Gotsadze et al., 2019; Mao et al., 2021b) and are consistent with learnings from countries that have seen relative success in achieving HIV control with strong government support, e.g. in Botswana, Burundi and Eswatini (Global Fund, 2020; Thornton, 2022; Bureau, 2023). While there is no single approach to achieve more sustainable, systems-oriented HIV programming, and strategies need to be locally crafted, these findings raise questions about the existing patterns and point to several key opportunities for EA partners to better support long-term HIV control and the achievement of universal health coverage.

First, respondents emphasized that bringing down the rate of new HIV infections will be critical for ensuring long-term control in the region, which requires making a stronger investment case for primary prevention. EA partners could support this first, by leveraging their technical resources to develop such an investment case, and second, by developing a clear and well-coordinated advocacy strategy in favour of investments in primary prevention. This will require internal shifts within EA partners to prioritize their own investments to address HIV incidence. Still, as respondents have made clear, governments facing transition will also need to sustain those already on ARVs and in the context of potentially declining resources for health, achieving these dual goals will be very challenging. Accordingly, EA partners should support governments to achieve greater efficiency by tailoring primary prevention strategies to a country’s specific needs (i.e. different packages of primary prevention strategies employed according to differences in the epidemiological and demographic environments), as well as integrating HIV prevention into existing systems where feasible. As a start, support from EA partners for targeted implementation research could guide more efficient investments and improve delivery and impact (Padian et al., 2011).

Second, technical assistance to support service integration is critical. Across the region, respondents described the need to develop clarity around the integration agenda and to make explicit what is to be integrated and how. While many respondents reiterated the need to build robust community health systems with HIV services fully integrated, this is not a universally shared vision, and systematic, context-specific assessments are needed for which functions should and should not be integrated at different levels of the health system. Systems integration will also require evaluating barriers locally and developing appropriate mitigation strategies. Two cross-cutting risks to integration identified by respondents are potential stakeholder resistance to integrated models and diminishing protections for marginalized (and criminalized) populations within mainstream service delivery. Identifying entrenched interests that may resist integration is a first step. Development partners must also address issues of alignment and harmonization, e.g., ensuring alignment of staff salaries between those personnel supported by EA and those within the government (Zakumumpa et al., 2021b), as well as integrating information systems. Special consideration will be needed around criminalized populations, particularly in light of recent harsh laws penalizing LGBTQ+ persons (PBS News Hour, 2023). HIV testing and awareness have been shown to decline while prevalence increases in criminalized settings, and there is a real risk that backsliding will occur with EA withdrawal, risking the health and safety of marginalized communities (Bigna and Nansseu, 2023; Lyons et al., 2023), as was seen in Romania following Global Fund transition (Flanagan et al., 2018).

Third, EA funders such as PEPFAR, the Global Fund and others need to meaningfully engage with local governments and NGOs to understand the barriers to institutionalization of HIV control activities within local bodies and leverage the human and organizational strengths within each implementing environment, fully recognizing potential pushback from international NGOs and other stakeholders. In particular, respondents were clear that there is a need to develop the institutional capacity of local organizations that are closest to the community, able to support community health systems, support service delivery and address persistent structural barriers to health. Local organizations have held a relatively marginalized position in addressing pressing health needs but can play a larger role with improvements to their governance and financial management capacity (McDonough and Rodríguez, 2020). Significant research will be needed to support this aim to identify the capabilities that will be required to sustain HIV control activities through local organizations and to evaluate effective strategies for building functional, technical, and adaptive capacities within local institutions.

Finally, recognizing that political will drives sustainability across domains, respondents underscored the importance of engagement strategies that speak to senior country leadership, including politicians and local NGO and advocacy groups (and not just technocrats). Developing these multifaceted strategies will require an understanding of electoral issues that may be influencing political decisions, as well as proactively addressing gaps around political will for primary prevention and KPs, e.g. addressing critically underserved populations like adolescent girls (UNAIDS, 2019; 2023). In the past, transition processes have been heavily donor-driven (Paina and Peters, 2012; Mao et al., 2021a), but to generate long-term political will for HIV control, country governments need to be at the centre, driving the sustainability agenda, setting transition parameters and identifying opportunities for short-term EA to facilitate transition. A recent initiative led by the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to develop an Africa-based HIV control working group to articulate the perspectives, priorities and needs of local actors pursuing long-term HIV control is a step in the right direction. EA partners should also prepare to invest in transition grants which allocate dedicated resources to managing transition processes and include embedded learning to capture lessons that can inform countries with a longer transition timeline.

We hope the findings from this analysis are timely, given the upcoming PEPFAR reauthorization (Moss and Kates, 2022) and new strategy eras for both the Global Fund and PEPFAR (PEPFAR, 2022; Global Fund, 2023b). We see these findings as helpful, not just in contexts where transition is imminent but also where there is substantial time to develop robust transition strategies to address the challenges outlined here. Still, our analysis is not without limitations. Our qualitative sample is useful in that it provides a regional perspective on common issues in HIV sustainability that may need addressing; of course, how each of these issues manifest will depend on the epidemiology of the epidemic in a given country, as well as the wider political, economic and health system environment. The quantitative analysis was relatively limited in scope and time period, intended to be indicative rather than comprehensive. An analysis that included PEPFAR and other EA funds would have painted a fuller picture. In addition, the Global Fund data were restricted to the module level, due to limited publicly available grant data at the intervention or activity level. Detailed analyses at the intervention or activity level could help provide more granular estimates of investments budgeted in the categories presented in our analysis. Similarly, the lack of available expenditure data (vs the budget data available to us) limited our ability to make conclusive statements about how Global Fund investments are spent in the country. Financial analyses for other countries within the region, or with shorter transition timelines, may also produce different results; however, our intention was to illustrate how key themes identified at a regional level may be reflected in given funding streams at the country level. We found the Oberth and Whiteside (2016) framework to be a helpful organizing frame for our analysis; however, emergent issues around institutional capacity building and alignment were not well captured in the existing domains. Additionally, while the authors acknowledge the domains of sustainability are interconnected, more could be done to understand these connections as they play out in various implementing environments. Nonetheless, our analysis has highlighted some important themes about the way EA practices can undermine sustainability and opportunities for rethinking operations to support long-term HIV control in the context of the universal health coverage agenda.

CONCLUSION

After >30 years of HIV exceptionalism, supported in the Southern and Eastern African region by high levels of EA, it seems both inevitable and appropriate for HIV services to become increasingly domestically supported and mainstreamed. However, this should not be achieved at the expense of HIV control. Our analysis demonstrates that while the transition and sustainability of HIV programmes have been on the global agenda for many years, to-date EA practices have often not supported progress in this direction. We have identified three principal ways in which development partners need to change their practices in support of long-term HIV control, namely (1) developing and investing in context-specific, evidence-based and efficient primary prevention strategies; (2) supporting the implementation of approaches that further the integration of HIV services into robust community health systems and (3) making serious investments in the capacity of local organizations. Underpinning all of this is the question of political commitment: development partners will need to work strategically and purposively with governments in the region to build political support to sustain (and improve) HIV outcomes, address structural barriers to improved prevention and breakdown organizational fiefdoms that have inhibited more efficient and integrated approaches.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge key informants who gave their time and insight to support this research. The authors would also like to thank Anas Ismail and Amanda Karapici from the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO for their help with proofreading the paper.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Footnotes

95% of people living with HIV know their HIV status; 95% of people who know they are HIV positive receive treatment and 95% of people on treatment have suppressed viral loads (UNAIDS, 2015).

Contributor Information

Abigail H Neel, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA.

Daniela C Rodríguez, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA.

Izukanji Sikazwe, Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ), 34620 Lukasu Road, Mass Media, Lusaka 10101, Zambia.

Yogan Pillay, Department of Global Health, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Peter Barron, School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa.

Shreya K Pereira, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA.

Sesupo Makakole-Nene, SCMN Global Health Consulting, 261 Middel Street, Pretoria 0181, South Africa.

Sara C Bennett, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA.

Funding

Funding was provided through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-016750). The funders were not involved in the development of this paper.

Author contributions

AHN, SCB, DCR, IS, YP and PB were involved in the c; AHN, SCB and DCR were involved in the d; AHN, SCB, DCR and SKP were involved in the data analysis and interpretation; AHN, SCB and SKP were involved in the drafting of the article; AHN, SCB, DCR, IS, YP, PB and SM-N were involved in the critical revision of the article; all authors were involved in thefinal approval of the version to be submitted.

Reflexivity statement

This paper represents a collective work reflecting the diverse positionalities of the authors. Researchers are diverse in terms of gender identity, seniority and citizenship. This article includes six authors who identify as women and two who identify as men. Two of the authors are early career researchers. Half are affiliated with high-income country institutions, while the other half are affiliated with institutions in low- and middle-income countries. Half of the authors also currently reside in Southern/Eastern Africa, and most have experience working and living in the region. The research team brings deep expertise in infectious disease control and HIV/AIDS, health policy and systems research, donor transition and sustainability and multi-methods research, as well as experience working in government and implementing organizations/NGOs, in addition to research institutions. These differing perspectives allowed for a diversity of views and experiences to be brought into the research. Our team has worked together on these issues over a period of many months and has taken a consultative and collaborative approach throughout the conceptualization, analysis and writing processes.

Ethical approval

Protocol and tools for the KIIs were reviewed by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board and deemed non-human subject research. Informed consent was obtained orally from each key informant prior to the recording of the interview.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- African Union . 2020. Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID 19) on the African Economy. Ethiopia: Addis Abab.

- Anyanwu JC, Salami AO. 2021. The impact of COVID‐19 on African economies: an introduction. African Development Review 33: S1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Singh S, Rodriguez D et al. 2015. Transitioning a large scale HIV/AIDS prevention program to local stakeholders: findings from the Avahan Transition Evaluation. PLoS One 10: e0136177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton A, Sangaramoorthy T. 2021. Exceptionalism at the end of AIDS. AMA Journal of Ethics 23: 410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigna JJ, Nansseu JR. 2023. Laws and policies against MSM and HIV control in Africa. The Lancet HIV 10: e148–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau The. 2023. Burundi achieves the 95-95-95 targets in the fight against HIV/AIDS—African Constituency Bureau. Kirkos, Ethiopia: UNDP, Regional Service Center for Africa. https://www.africanconstituency.org/burundi-achieves-the-95-95-95-targets-in-the-fight-against-hiv-aids/.

- Chin J, Mann JM. 1990. HIV infections and AIDS in the 1990s. Annual Review of Public Health 11: 127–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock KMD, Johnson AM. 1998. From exceptionalism to normalisation: a reappraisal of attitudes and practice around HIV testing. Bmj 316: 290–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell JW, Clark ViLP. 2017. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd edn. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Network GB of DHFC. Dieleman JL, Haakenstad A, Micah A et al. 2018. Spending on health and HIV/AIDS: domestic health spending and development assistance in 188 countries, 1995–2015. The Lancet 391: 1799–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan K, Rees H, Huffstetler H et al. 2018. Donor Transitions from HIV Programs: What is the impact on vulnerable populations? Center for Policy Impact in Global Health and Pharos Global Health Advisors.

- Global Fund . The Global Fund Data Explorer. Geneva, Switzerland: Global Fund.

- Global Fund. 2016. The Global Fund Sustainability, Transition and Co-financing Policy. The Global Fund 35th Board Meeting, 26-27 April 2016, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. [Google Scholar]

- Global Fund . 2020. Eswatini Meets Global 95-95-95 HIV Target – Stories – The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Geneva, Switzerland: Global Fund.

- Global Fund . 2021. Guidance for Sustainability and Transition Assessments and Planning for National HIV and TB Responses. Geneva, Switzerland: Global Fund.

- Global Fund . 2022. Results Report 2022. Geneva, Switzerland: Global Fund.

- Global Fund . 2023a. Projected Transitions from Global Fund Country Allocations by 2028: Projections by Component. Geneva, Switzerland: Global Fund.

- Global Fund . 2023b. Fighting Pandemics and Building a Healthier and More Equitable World Global Fund Strategy (2023-2028). Geneva, Switzerland: Global Fund.

- Gotsadze G, Chikovani I, Sulaberidze L et al. 2019. The challenges of transition from donor-funded programs: results from a theory-driven multi-country comparative case study of programs in Eastern Europe and Central Asia supported by the Global Fund. Global Health: Science and Practice 7: 258–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruen RL, Elliott JH, Nolan ML et al. 2008. Sustainability science: an integrated approach for health-programme planning. The Lancet 372: 1579–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffstetler HE, Bandara S, Bharali I et al. 2022. The impacts of donor transitions on health systems in middle-income countries: a scoping review. Health Policy and Planning 37: 1188–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerve AS, Jerve AM. 2008. Managing Aid Exit and Transformation. Lessons from Botswana, Eritrea, India, Malawi and South Africa. Synthesis Report. Stockholm: Netherland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Kates J, Wexler A, Lief E. 2020. Donor Government Funding for HIV in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in 2019. San Francisco, California, USA: Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and UNAIDS.

- Lantos T, Henry J. USG. H.R.5501 . 2008. Hyde United States Global Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Reauthorization Act of 2008. Congress.gov. Washington, D.C., USA: Library of Congress. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons CE, Rwema JOT, Makofane K et al. 2023. Associations between punitive policies and legal barriers to consensual same-sex sexual acts and HIV among gay men and other men who have sex with men in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicountry, respondent-driven sampling survey. The Lancet HIV 10: e186–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao W, McDade KK, Bharali I et al. 2021a. Transitioning from health aid: a scoping review of transition readiness assessment tools. Duke Global Working Paper Series No. 27. 10.2139/ssrn.3779348. [DOI]

- Mao W, McDade KK, Huffstetler HE et al. 2021b. Transitioning from donor aid for health: perspectives of national stakeholders in Ghana. BMJ Global Health 6: e003896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough A, Rodríguez DC. 2020. How donors support civil society as government accountability advocates: a review of strategies and implications for transition of donor funding in global health. Globalization and Health 16: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melesse TM. 2021. International aid to Africa needs an overhaul. Tips on what needs to change - World ReliefWeb. Relief Web. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/international-aid-africa-needs-overhaul-tips-what-needs-change, accessed 15 January 2021.

- Moore LV, Roux AVD. 2011. Associations of Neighborhood Characteristics With the Location and Type of Food Stores. American Journal of Public Health 96: 325–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss K, Kates J. 2022. PEPFAR Reauthorization: Side-by-Side of Legislation Over Time. KFF. Washington D.C., USA: KFF. https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/pepfar-reauthorization-side-by-side-of-existing-and-proposed-legislation/. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo D. 2009. Dead Aid: Why Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Oberth G, Whiteside A. 2016. What does sustainability mean in the HIV and AIDS response? African Journal of AIDS Research 15: 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the General Inspector . 2019. Audit Report Managing Investments in Resilient and Sustainable Systems for Health. Geneva, Switzerland: The Global Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Okere NE, Lennox L, Urlings L et al. 2021. Exploring sustainability in the era of differentiated HIV service delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 87: 1055–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padian NS, McCoy SI, Karim SSA et al. 2011. HIV prevention transformed: the new prevention research agenda. The Lancet 378: 269–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paina L, Peters DH. 2012. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy and Planning 27: 365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paina L, Rodriguez DC, Zakumumpa H et al. 2023. Geographic prioritisation in Kenya and Uganda: a power analysis of donor transition. BMJ Global Health 8: e010499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PBS News Hour . 2023. Where African countries stand in their struggle toward more inclusive LGBTQ+ laws. PBS NewsHour. [Google Scholar]

- PEPFAR . 2022. PEPFAR’s Five-Year Strategy: Fulfilling America’s Promise to End the HIV/AIDS Pandemic by 2030. Washington D.C., USA.

- Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. 2011. An Agenda for Research on the Sustainability of Public Health Programs. American Journal of Public Health 101: 2059–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen AK, Farrell MM, Vandenbroucke MF et al. 2015. Applying lessons learned from the USAID family planning graduation experience to the GAVI graduation process. Health Policy and Planning 30: 687–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff ZC, Sparkes S, Skarphedinsdottir M et al. 2022. Rethinking external assistance for health. Health Policy and Planning 37: 932–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman R. 2018. Projected health financing transitions: timeline and magnitude. SSRN Electronic Journal. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton J. 2022. Botswana’s HIV/AIDS success. The Lancet 400: 480–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . 2015. Understanding Fast-Track Accelerating Action to End the AIDS Epidemic by 2030. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . 2019. Women and HIV—A Spotlight on Adolescent Girls and Young Women. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS . 2021. With the right investment, Aids can be over a US$ 29 Billion Investment to end Aids by the end of the Decade. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS . 2023. We’ve Got the Power—Women, Adolescent Girls and the HIV Response. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Vogus A, Graff K. 2015. PEPFAR transitions to country ownership: review of past donor transitions and application of lessons learned to the Eastern Caribbean. Global Health: Science and Practice 3: 274–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2016. Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV 2016-2021 Towards Ending AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Zakumumpa H, Paina L, Wilhelm J et al. 2021a. The impact of loss of PEPFAR support on HIV services at health facilities in low-burden districts in Uganda. BMC Health Services Research 21: 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakumumpa H, Rujumba J, Amde W et al. 2021b. Transitioning health workers from PEPFAR contracts to the Uganda government payroll. Health Policy and Planning 36: 1397–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.