Abstract

In this case series, we describe the use of invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing (iCPET) to diagnose heart failure due to preload reserve failure in two patients with progressive dyspnoea. We demonstrate that underlying liver disease contributes to preload reserve failure as a cause of exertional dysfunction. In liver diseases such as non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), fibrotic changes to the sinusoidal liver architecture occur leading to an increased transhepatic sinusoidal pressure gradient. Even at the earliest stage of hepatic fibrosis in patients with NAFLD, changes in hepatic blood flow are seen due to outflow block in the sinusoidal area. In this way, changes to the sinusoidal liver architecture can lead to limitations in preload reserve. This case series describes two patients with exertional dyspnoea found to have preload failure on iCPET due to underlying liver disease.

Keywords: Invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing, Preload reserve failure, Heart failure, Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

Introduction

While non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has been implicated in the development of heart failure with concomitant increase in filling pressures, 1 NAFLD has also been described in the literature as a cause of preload reserve failure. 2 In this case series, invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing (iCPET) is used to diagnose heart failure due to preload reserve failure in two patients with progressive dyspnoea. These cases demonstrate that underlying liver disease can contribute to preload reserve failure as a cause of exertional dysfunction.

Case report

Case 1

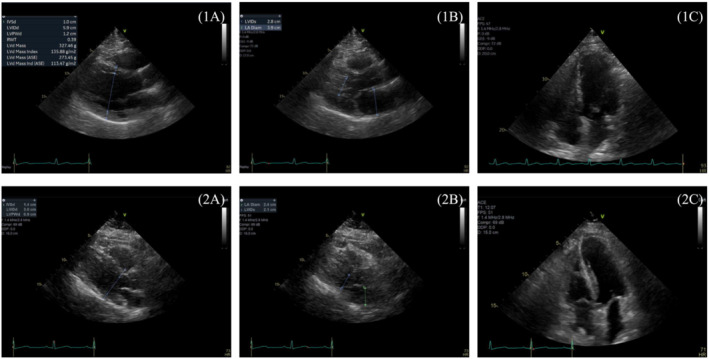

A 42‐year‐old male with past medical history of type II diabetes mellitus (haemoglobin A1c 6.8), hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidaemia (HLD), asthma, and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) presented with progressive dyspnoea on exertion. The patient had a history of non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis with liver ultrasound demonstrating enlarged liver with fatty infiltration. Laboratory analysis was significant for serum creatinine of 1.3 mg/dL with aspartate aminotransferase of 296 U/L and alanine aminotransferase of 379 U/L with normal bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase. Complete blood count was normal. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed mildly enlarged left ventricle with normal left and right ventricular function (Figure 1 ). The patient's medications were albuterol inhaler, losartan, metformin, omeprazole, and ezetimibe. He was not taking any diuretics.

Figure 1.

Representative transthoracic echocardiograms from Case 1 (1A–C) and Case 2 (2A–C).

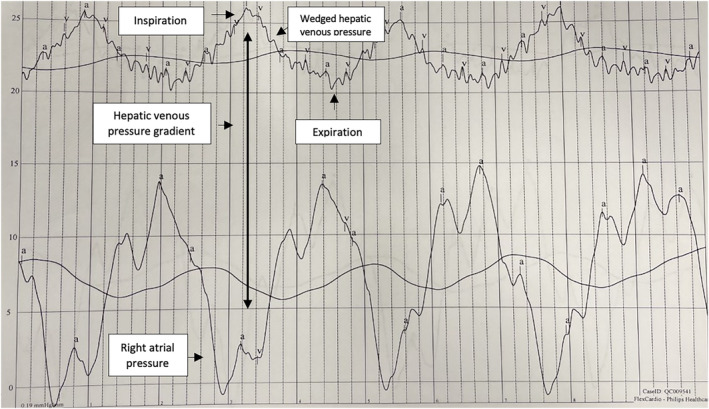

Supine iCPET was performed for further evaluation of his dyspnoea, with intracardiac pressures measured at rest, with leg raise, and with exercise. Table 1 summarizes the mean pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), and cardiac output (CO) at these stages of iCPET. In this case, while the PCWP peaked at 26 mmHg with 20 W of exercise, the PCWP steadily decreased with 100 and 180 W of exercise. Decreasing PCWP in the setting of high CO raised concern for heart failure due to preload failure in the setting of underlying liver disease. At rest, the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) was elevated to approximately 15 mmHg. When the pressures in the right atrium and wedged hepatic venous pressure (WHVP) were simultaneously recorded for 30 s, allowing for observation of variability with the respiratory cycle, the patient's HVPG increased to approximately 23 mmHg with inspiration (Figure 2 ), indicating a significant gradient across the liver. The patient was subsequently referred to hepatology.

Table 1.

Invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing and transthoracic echocardiogram data for Case 1

| mPAP (mmHg) | PCWP (mmHg) | CO (L/min) | HVPG | Transthoracic echocardiogram | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting | 25 | 17 | 8.8 |

Resting HVPG: 15 mmHg HVPG with inspiration: 23 mmHg |

LVEF > 55%, normal RV systolic function, and no diastolic dysfunction. LAVi of 28 mL/m2, max IVC of 1.6 cm, and SWT of 1.0 cm |

| Leg raise | 32 | 25 | 11.0 | ||

| 20 W | 37 | 26 | 14.6 | ||

| 100 W | 37 | 23 | 16.6 | ||

| 180 W (peak exercise) | 35 | 20 | 21.0 |

CO, cardiac output; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; IVC, inferior vena cava; LAVi, left atrial volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; RV, right ventricle; SWT, septal wall thickness.

Decreasing PCWP in the setting of high CO raised concern for heart failure due to preload failure.

Figure 2.

Pressure tracing from Case 1: The patient's hepatic venous pressure gradient increased to approximately 23 mmHg with inspiration when right atrial and wedge hepatic venous pressures were simultaneously recorded.

Case 2

A 79‐year‐old woman with past medical history of HTN, HLD, pre‐diabetes, and chronic kidney disease stage 3 presented to cardiology clinic with dyspnoea on exertion. She endorsed chronic dyspnoea on exertion for years with progressive subacute worsening over the past 6 months. Relevant cardiovascular medications included amlodipine of 10 mg daily, furosemide of 20 mg daily, empagliflozin of 10 mg daily, and spironolactone of 25 mg daily. She did not drink alcohol and had no family history of liver disease.

Laboratory analysis was notable for normal electrolytes with serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase of 18 U/L, alanine aminotransferase of 17 U/L, alkaline phosphatase mildly elevated at 105 U/L, normal cell counts, and haemoglobin A1c of 5.7%. An echocardiogram stress test showed mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy with grade 1 relaxation abnormality. iCPET is shown in Table 2 . Change in PCWP over change in CO from rest to peak exertion was 4.57 mmHg/L/min. Peak oxygen uptake (VO2) was 11 mg/kg/min, which was 75.9% of predicted. The minute ventilation to carbon dioxide production ratio (VE/VCO2) was 36 mg/kg/min, which was 114% of predicted. The respiratory exchange ratio was 1.09. The echocardiographic appearance of the right and left ventricle suggested ventricular underfilling with a supranormal left ventricular ejection fraction with exercise (Figure 1 ). An investigation into the contribution of liver disease into the observed exercise physiology followed.

Table 2.

Invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing and stress echocardiogram data for Case 2

| mPAP (mmHg) | PCWP (mmHg) | CO (L/min) | HVPG | Stress echocardiogram | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting | 17 | 7 | 4.8 |

Resting HVPG: 5 mmHg HVPG with inspiration: 12 mmHg |

LVEF > 55% and grade 1 diastolic dysfunction |

| Leg raise | 21 | 10 | 5.3 | ||

| 20 W | 22 | 14 | 4.8 | ||

| 60 W (peak exercise) | 30 | 23 | 8.3 |

CO, cardiac output; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.

The HVPG increased to 12 mmHg with inspiration in Case 2 raising concern for underlying liver disease.

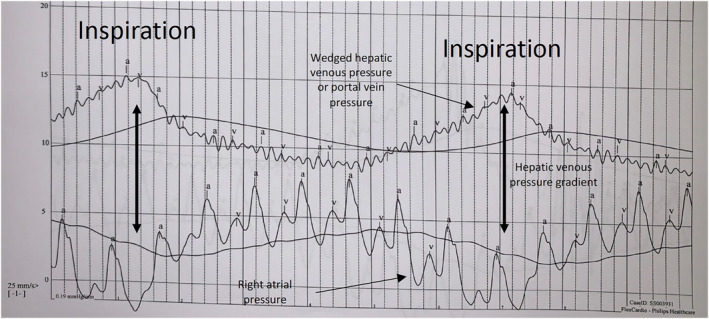

At rest, the HVPG was 5 mmHg (high normal). However, when the pressures in the right atrium and WHVP were simultaneously recorded for 30 s, allowing for observation of variability with the respiratory cycle, the patient's HVPG increased to approximately 12 mmHg with inspiration (Figure 3 ). Given an elevated HVPG, a liver ultrasound was subsequently obtained, which showed coarsened echotexture with diffusely increased echogenicity. The patient was subsequently referred to hepatology. The presumptive diagnosis was preload reserve failure in the setting of previously undiagnosed NAFLD. Given suspicion for a preload‐dependent state, the patient's diuretics were discontinued with moderate improvement in her symptoms.

Figure 3.

Pressure tracing from Case 2: The patient's hepatic venous pressure gradient increased to approximately 12 mmHg with inspiration when right atrial and wedged hepatic venous pressures were simultaneously recorded.

Discussion

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a complex and heterogenous clinical syndrome characterized by diastolic and systolic reserve abnormalities, endothelial dysfunction, and preload reserve failure. 3 While NAFLD has been implicated in the development of HFpEF due to increased filling pressures, 1 NAFLD has also been described in the literature as a cause of preload reserve failure. Preload reserve failure in NAFLD leading to an obstructive HFpEF phenotype has been described in the literature as impaired venous return to the heart due to increased resistance across the hepatic sinusoids. In a state of increased cardiac demand, such as with exercise, preload reserve failure limits CO, leading to exertional limitations and symptoms consistent with HFpEF but without elevated filling pressures. 3

Supine and upright iCPET is the gold standard for diagnosis of HFpEF. Early diagnosis of HFpEF can be challenging, as patients often have normal resting cardiac filling pressures. 4 However, exercise haemodynamic testing has emerged as a way to diagnose early HFpEF in euvolaemic patients without indicators of volume overload. 5 Supine iCPET has been used to diagnose a preload reserve failure phenotype of HFpEF leading to dyspnoea on exertion. 6

The traditional gold standard definition of HFpEF in iCPET is exercise‐induced PCWP ≥ 25 mmHg 5 or ratio of PCWP to CO slope > 2 mmHg/L/min. 4 Borlaug et al. reported a study of 55 patients with dyspnoea on exertion but normal resting haemodynamics that a PCWP ≥ 25 mmHg is to be considered pathological and describes HFpEF, 5 while Eisman et al. described a ratio of PCWP to CO > 2 mmHg/L/min during iCPET as a way to diagnose HFpEF. 4 A ratio > 2 mmHg/L/min was associated with reduced peak VO2 and adverse cardiac outcomes. 4 In the first case, the PCWP elevated to >25 mmHg with exercise. In the second case, while the patient did not have an exercise‐induced PCWP ≥ 25 mmHg, she did have a PCWP to CO slope of 4.57 mmHg/L/min, indicating a diagnosis of HFpEF.

Oldham et al. in an iCPET study of patients with unexplained dyspnoea found that low ventricular filling pressures during exercise were resulting in a blunted CO and inability to meet physiologic circulatory demands, suggesting that preload failure may be the aetiology of these patients' dyspnoea. 7 In a normal preload responsive heart, during spontaneous breathing, inspiration decreases intrathoracic pressure and increases intra‐abdominal pressure, increasing preload of the right ventricle. 8 Further, in exercise states, increased venous return occurs via contraction of skeletal muscle and abdominal compartments leading to increased stroke volume and CO. 9 In preload reserve failure, it has been hypothesized that any individual or a combination of factors such as autonomic dysfunction, increased splanchnic vascular capacitance, and impairment of blood flow across the hepatic and portal veins due to an increased hepatic sinusoidal pressure gradient leads to this phenotype. 2

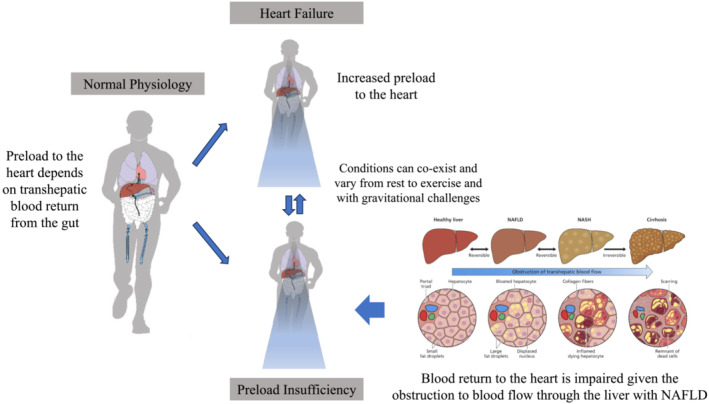

In the first case, the PCWP peaked at 20 W of exercise and then steadily downtrended despite increased exercise demands, indicating a preload‐dependent state due to liver disease. It has been proposed that liver disease may be a cause of preload reserve failure due to an increased hepatic sinusoidal pressure gradient. In liver diseases such as NAFLD, fibrotic changes to the sinusoidal liver architecture can occur leading to an increased transhepatic sinusoidal pressure gradient. This leads to a significant impairment in venous return, as driving pressures from the splanchnic compartment to the right heart are low and not designed to overcome resistance. Even at the earliest stage of hepatic fibrosis in patients with NAFLD, changes in hepatic blood flow are seen due to outflow block in the sinusoidal area (Figure 4 ). 10 In this way, changes to the sinusoidal liver architecture can lead to limitations in preload reserve, as almost a quarter of circulating blood volume must pass the liver via the portal vein and hepatic artery to return to the heart. 2 Patients with NAFLD can have HFpEF with diastolic dysfunction due to known metabolic risk factors, while experiencing preload failure due to transhepatic obstruction, preventing volume loading of the heart. Risk factors for diastolic dysfunction include age, HTN, diabetes mellitus, and left ventricular hypertrophy. 11 Left ventricular filling is determined by the rate of left ventricular relaxation and the left atrial pressure at the time of mitral valve opening. 12 In a normal functioning heart, as preload increases, the CO of the heart increases based on the Frank–Starling curve. 13 , 14 Notably, diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF can co‐exist with decreased filling of the heart in the setting of transhepatic obstruction. To a certain degree, the reduction in preload observed with transhepatic obstruction could be protective of excessive pressure elevations in patients with diastolic dysfunction/HFpEF with physical activity or even rest.

Figure 4.

Diagram demonstrating pathophysiology of preload reserve failure due to non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). As liver fibrosis advances, changes in liver architecture obstruct transhepatic blood flow leading to heart failure. NASH, non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis. Source: Figure adapted from Fudim et al. 3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34869957/.

The patient in Case 1 had risk factors for NAFLD including type II diabetes mellitus, HTN, HLD, and OSA. Interestingly, OSA is associated with development of heart failure through neurohumoral and inflammatory mechanisms, including increased sympathetic nervous system activity and repeated elevations in systemic blood pressure due to hypoxia. 15 In this case, the patient's OSA likely contributed to his development of heart failure, though did not explain his elevated HVPG. The metabolic factors of type II diabetes mellitus, HTN, and HLD contributed to both the development of NAFLD and OSA in this patient. The patient in Case 1 met the traditional criteria for diagnosis of HFpEF on iCPET with an exercise‐induced PCWP > 25 mmHg, as his PCWP increased to 26 mmHg with 20 W of exercise.

Invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing revealed a significant gradient across the liver. At rest, the HVPG was elevated to 15 mmHg, and when the pressures in the right atrium and WHVP were simultaneously recorded, the patient's HVPG increased to 23 mmHg with inspiration, indicative of a significant gradient across the liver. Underlying liver disease was confirmed with a liver ultrasound showing an enlarged liver with fatty infiltration.

On exercise testing, the patient's CO rose, as expected, with increasing exertion. However, despite a rising CO, the patient's PCWP peaked at 26 mmHg at 20 W of exercise and downtrended to 23 and 20 mmHg at 100 and 180 W of exercise, respectively, despite the CO rising to 16.6 and 21 L/min at these exercise levels. It is expected that an increase in CO is paralleled by an increase in wedge pressure. Yet, in this case, this was not seen presumably due to a limitation of preload reserve.

The patient in Case 2 had risk factors for NAFLD including HTN, HLD, and pre‐diabetes. She presented with significant dyspnoea on exertion and was found on iCPET to have an HVPG of 12 mmHg with inspiration, suggesting a gradient across the liver and a preload‐dependent state. The HVPG is the best available method to evaluate for the presence and severity of portal HTN. An HVPG score ≥ 6 mmHg indicates portal HTN, while HVPG > 10 mmHg represents clinically significant portal HTN. The HVPG represents the gradient between the portal vein and the hepatic vein. The WHVP estimates portal vein pressure by occlusive hepatic vein catheterization, whereas the free hepatic venous pressure (FHVP) is a measure of the pressure in the hepatic vein. Thus, the HVPG is calculated by subtracting the FHVP from the WHVP. In practice, the FHVP is measured by a deflated balloon catheter in the right hepatic vein, with WHVP measured when the balloon is inflated. 16 Typically, there is a time difference between the measurement of the FHVP and the WHVP given the inflation of the balloon. However, in the cases described above, the WHVP and the FHVP were measured simultaneously by catheters in the right atrium and hepatic wedge, allowing for the accurate measurement of simultaneous pressures during the respiratory cycle. In the second case, the increased HVPG of 12 mmHg during inspiration suggested obstruction to blood flow across the liver. A liver ultrasound was subsequently obtained, which showed a coarsened echotexture of the liver with diffusely increased echogenicity, in a patient with risk factors for NAFLD. Due to concern for preload dependence, the patient's diuretic regimen of furosemide of 20 mg daily, empagliflozin of 10 mg daily, and spironolactone of 25 mg daily was discontinued. With cessation of these medications, the patient's symptoms moderately improved. We hypothesize that diuretics were further reducing preload in this patient, leading to worsened dyspnoea on exertion.

The traditional gold standard definition of HFpEF in iCPET is exercise‐induced PCWP ≥ 25 mmHg 5 or ratio of PCWP to CO slope > 2 mmHg/L/min. 4 A limitation of the second case is that the PCWP peaked at 23 mmHg at 60 W of exercise and did not meet the 25 mmHg threshold. The patient did however meet criteria for diagnosis of HFpEF with a PCWP to CO slope of 4.57 mmHg/L/min. Further exercise exertion may have yielded additional diagnostic information.

In this case series, use of iCPET to diagnose heart failure due to preload reserve failure in two patients with underlying liver disease is described. Further research is needed to understand the pathophysiology of preload reserve failure.

Conflict of interest

C.G.A., P.P., and K.P. declare no conflicts of interest. M.F. was supported by the American Heart Association (20IPA35310955), Doris Duke, Bayer, Bodyport, and Verily. He receives consulting fees from Abbott, Ajax, Alio Health, Alleviant, Audicor, Axon Therapies, Bayer, Bodyguide, Bodyport, Boston Scientific, Broadview, Cadence, Cardionomics, Coridea, CVRx, Daxor, Deerfield Catalyst, Edwards Lifesciences, EKO, Feldschuh Foundation, Fire1, Galvani, Gradient, Hatteras, Impulse Dynamics, Intershunt, Medtronic, Merck, NIMedical, Novo Nordisk, NucleusRx, NXT Biomedical, Pharmacosmos, PreHealth, ReCor, Shifamed, Splendo, Sumacor, SyMap, Verily, Vironix, Viscardia, and Zoll.

Funding

Dr Fudim was supported by the American Heart Association (20IPA35310955).

Ahlers, C. G. , Patel, P. , Parikh, K. , and Fudim, M. (2024) Use of invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing to diagnose preload reserve failure in patients with liver disease. ESC Heart Failure, 11: 587–593. 10.1002/ehf2.14598.

References

- 1. VanWagner LB, Wilcox JE, Colangelo LA, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Carr JJ, Lima JA, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with subclinical myocardial remodeling and dysfunction: A population‐based study. Hepatology 2015;62:773‐783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fudim M, Sobotka PA, Dunlap ME. Extracardiac abnormalities of preload reserve: Mechanisms underlying exercise limitation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, autonomic dysfunction, and liver disease. Circ Heart Fail 2021;14:e007308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Salah HM, Pandey A, Soloveva A, Abdelmalek MF, Diehl AM, Moylan CA, et al. Relationship of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2021;6:918‐932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eisman AS, Shah RV, Dhakal BP, Pappagianopoulos PP, Wooster L, Bailey C, et al. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure patterns during exercise predict exercise capacity and incident heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2018;11:e004750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CS, Redfield MM. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:588‐595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rao VN, Kelsey MD, Blazing MA, Pagidipati NJ, Fortin TA, Fudim M. Unexplained dyspnea on exertion: The difference the right test can make. Circ Heart Fail 2022;15:e008982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oldham WM, Lewis GD, Opotowsky AR, Waxman AB, Systrom DM. Unexplained exertional dyspnea caused by low ventricular filling pressures: Results from clinical invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Pulm Circ 2016;6:55‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Préau S, Dewavrin F, Soland V, Bortolotti P, Colling D, Chagnon JL, et al. Hemodynamic changes during a deep inspiration maneuver predict fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients. Cardiol Res Pract 2012;2012:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fudim M, Zhong L, Patel KV, Khera R, Abdelmalek MF, Diehl AM, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e021654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hirooka M, Koizumi Y, Miyake T, Ochi H, Tokumoto Y, Tada F, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Portal hypertension due to outflow block in patients without cirrhosis. Radiology 2015;274:597‐604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jeong EM, Dudley SC Jr. Diastolic dysfunction. Circ J 2015;79:470‐477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fukuta H, Little WC. The cardiac cycle and the physiologic basis of left ventricular contraction, ejection, relaxation, and filling. Heart Fail Clin 2008;4:1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dori G, Rudman M, Lichtenstein O, Schliamser JE. Ejection fraction in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction is greater than that in controls—A mechanism facilitating left ventricular filling and maximizing cardiac output. Med Hypotheses 2012;79:384‐387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parasuraman SK, Loudon BL, Lowery C, Cameron D, Singh S, Schwarz K, et al. Diastolic ventricular interaction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e010114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khattak HK, Hayat F, Pamboukian SV, Hahn HS, Schwartz BP, Stein PK. Obstructive sleep apnea in heart failure: Review of prevalence, treatment with continuous positive airway pressure, and prognosis. Tex Heart Inst J 2018;45:151‐161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suk KT. Hepatic venous pressure gradient: Clinical use in chronic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2014;20:6‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]