Abstract

Heparin, dextran sulfate, pentosan polysulfate, and a sulfated synthetic copolymer of acrylic acid and vinyl alcohol were shown to be potent inhibitors of Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity for cultured human epithelial cells. Despite their potent antichlamydial activity in vitro, neither heparin nor dextran sulfate was effective in inhibiting the infectivity of C. trachomatis in a murine model of chlamydial infection of the female genital tract.

Genital tract infection caused by the obligate intracellular bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common sexually transmitted disease (STD) in the United States (15, 16). In women, ascending infections of the genital tract can produce serious sequelae that include pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and reproductive disability (4, 5, 9, 12). It is estimated that the cost of treating chlamydial infections and their sequelae in the United States alone approaches $2.2 billion annually. Control of chlamydial STDs has focused on four areas of intervention strategies: (i) improved diagnosis and treatment of subclinical infections, (ii) behavioral modification, (iii) vaccination, and (iv) microbicides. Because many chlamydial infections are subclinical, early antibiotic intervention has not been highly effective in controlling chlamydial STDs. Although advances are being made in understanding the immune mechanism(s) that confers protection against chlamydial genital tract infection in animal models, an efficacious vaccine for use in humans does not appear to be forthcoming in the near future. Antichlamydial microbicides have been implicated as one of the most promising control measures, particularly for women, since they could be easily administered intravaginally prior to sexual intercourse.

We (19) and others (22, 23) have shown that the glycosaminoglycans are potent inhibitors of chlamydial infectivity for cultured human cervical epithelial cells. Although currently controversial, we have proposed that chlamydial attachment to host cells is mediated through the specific binding of the chlamydial major outer membrane protein to host cell glycoaminoglycan receptors of the heparan sulfate family (19). Chlamydial attachment to epithelial cells is an initial and critical step in the pathogenesis of infection; therefore, irrespective of the mechanism(s) employed, inhibition of chlamydial adherence to cervical epithelial cells by vaginally administered glycosaminoglycans or structurally similar compounds that exhibit antichlamydial activity would represent a plausible approach for preventing or controlling chlamydial infections in women.

In this study, we have investigated sulfated polysaccharides such as heparin, dextran sulfate (DS), pentosan polysulfate (PPS), and a sulfated synthetic polymer as potential antichlamydial microbicides. These compounds have been reported to have inhibitory effects on other STD pathogens, such as human immunodeficiency virus (1–3, 11, 13, 20), herpes simplex virus (14), and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (8, 21). Our findings show that these compounds are also potent inhibitors of chlamydial infectivity in vitro; however, they are not efficacious as antichlamydial microbicides in in vivo models of chlamydial infection of the female genital tract.

Chlamydiae.

The C. trachomatis strain UW-31 (serovar D) and the mouse pneumonitis (MoPn) strain were grown in HeLa 229 cells, and elementary bodies (EBs) were purified and inclusion-forming units (IFUs) were determined as previously described (6).

Sulfated polysaccharides and synthetic sulfated polymer.

The compounds used were heparin, DS (MW, 1,000 [DS-1,000]; Mw, 5,000 [DS-5,000]; Mw, 10,000 [DS-10,000]), PPS (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and a copolymer of acrylic acid with vinylalcohol sulfate (ratio, 1:9; 50% sulfonation of hydroxyl groups), referred to hereafter in this work as PAVAS, obtained from E. de Clerq (Raga Institute for Medical Research, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium) through John Swanson (Rocky Mountain Laboratory, Hamilton, Mont.).

In vitro antichlamydial activity.

C. trachomatis serovar D and MoPn EBs were diluted in 10 mM sodium phosphate–0.25 M sucrose–5 mM glutamic acid (SPG), pH 7.4, to contain 6 × 105 and 5 × 106 IFUs, respectively. Serial 10-fold dilutions (200 to 0.02 μg/ml) of each compound were prepared in SPG, and equal volumes of the diluted compounds were mixed with the chlamydial suspensions. A 200-μl volume of this mixture was inoculated onto washed HeLa 229 monolayers and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The monolayers were washed, refed with medium, and incubated for an additional 30 h at 37°C. The monolayers were then washed and fixed with methanol, and chlamydial inclusions were stained and visualized by indirect immunofluorescence using a genus-specific antilipopolysaccharide monoclonal antibody (EVI-H1). The inhibitory activity of compounds is expressed as percent reduction of IFUs and was calculated as previously described (17).

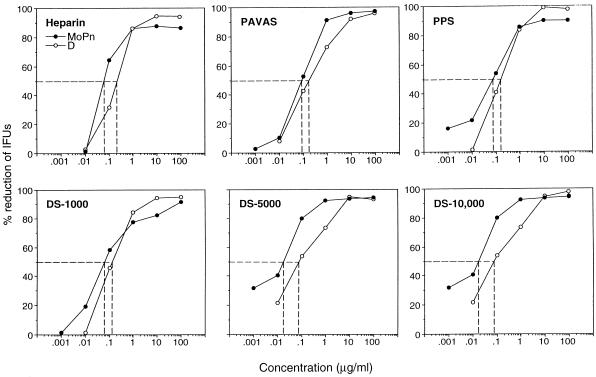

The dose response inhibition of infectivity and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of each compound for serovar D and MoPn EBs assayed on HeLa 229 cells are shown in Fig. 1. Heparin, DS-1000, DS-5000, DS-10,000, PPS, and PAVAS all exhibited a dose-dependent inhibition of infectivity for both C. trachomatis strains. Maximal inhibition of infectivity (95% or greater reduction in IFUs) for both chlamydial strains was obtained at compound concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 μg/ml. The IC50s of all compounds for chlamydial infectivity of HeLa 229 cells were very similar, ranging from 0.02 to 0.12 μg/ml. Inhibition of infectivity was not related to the MW of polysulfated compounds, as DS-1,000, DS-5,000, and DS-10,000 were equally effective in their inhibitory properties, nor were there differences in the inhibitory activities among sulfated polysaccharides and PAVAS (a sulfated synthetic polymer). These findings demonstrate that sulfated polysaccharides and PAVAS are potent inhibitors of chlamydial infectivity in vitro and therefore warrant further experimentation to evaluate their ability to function as inhibitors of chlamydial infectivity in vivo.

FIG. 1.

Inhibitory activities of sulfated polysaccharides and a synthetic sulfated polymer on C. trachomatis infectivity for HeLa 229 cells. C. trachomatis serovar D and MoPn EBs were mixed with different concentrations of each compound and then assayed for infectivity following inoculation onto monolayers of HeLa 229 cells. The IC50s of each compound for both chlamydial strains are shown by the dotted lines.

In vivo antichlamydial activity.

For in vivo studies, 6- to 8-week-old female C57BL/10 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were used. Mice were given food and water ad libitum and were maintained under Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited housing conditions. The chlamydial challenge strain used for these studies was MoPn. It was selected because of its well-documented infectivity properties in the murine model. Heparin and DS-10,000 were tested as inhibitors in in vivo assays of chlamydial infectivity. Two experimental approaches were investigated to assess the potential inhibitory activity of these compounds in vivo. The first was to preincubate chlamydiae with each compound in vitro and then challenge mice intravaginally, and the second was to administer the compounds alone into the vaginal vaults of mice, followed immediately by an infectious chlamydial challenge. For the first experiment, 50 μl of MoPn EBs (6 × 105 IFUs/ml) was mixed with 50 μl of SPG containing either heparin or DS-10,000 (2 or 100 mg/ml). A 5-μl volume of the mixture (1,500 IFUs equals 100 50% infectious doses [ID50s]) was then inoculated into the vaginal vaults of 5 mice. In the second experimental group, 20 μl of heparin or DS-10,000 (100 mg/ml in SPG) was inoculated into the vaginal vaults of five mice; this was immediately followed by a 5-μl (100 ID50) challenge of MoPn EBs. Control mice for each group either were inoculated intravaginally with 5 μl (100 ID50) of untreated MoPn EBs or received 20 μl of SPG intravaginally prior to chlamydial challenge. Mice received subcutaneous injections of 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera; Upjohn, Kalamazoo, Mich.) in 100 μl of saline 10 and 3 days prior to challenge to synchronize estrus. The kinetics of infection were monitored by swabbing the vaginal vault with Calgiswabs (Spectrum Medical Industries, Los Angeles, Calif.) at selected intervals after challenge. Recoverable organisms were titrated on HeLa 229 cell monolayers as described previously (18).

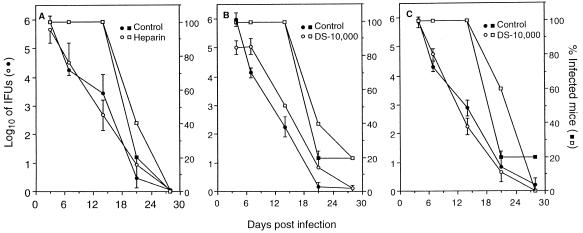

The percentage of mice infected and the recovery of chlamydiae from cervico-vaginal swabs of mice in each experimental group are shown in Fig. 2. Figure 2A and B show the effect of preincubation of chlamydiae with either heparin or DS-10,000 (2 mg/ml) prior to intravaginal challenge of mice. There was no effect of either compound on the percentage of mice infected, cervico-vaginal shedding of chlamydiae, or duration of infection. Increasing the concentration of either compound (100 mg/ml) was also without effect on chlamydial infectivity (data not shown). Figure 2C shows the effect of instillation of each compound into the vaginal vault prior to infectious chlamydial challenge. Similarly, the presence of either compound in the vaginal vault prior to challenge had no demonstrable effect on the percentage of mice infected or the kinetics of infection. Thus, although both heparin and DS-10,000 exhibited potent antichlamydial inhibitory activity in vitro neither compound was effective in preventing chlamydial infection in vivo. This lack of efficacy was surprising since the concentrations of heparin and DS-10,000 were 100- to 5,000-fold greater than that required to achieve maximum inhibition of chlamydial infectivity in vitro (Fig. 1). There are several possible explanations for these disparate results. The first possibility is that inhibition of infectivity was incomplete, and the small number of infectious organisms that were not inhibited by the compounds was sufficient to establish a productive infection in vivo. This may in fact be the case, since as few as 15 IFUs of the MoPn EBs are sufficient to infect mice intravaginally (10). A second possibility is that differences exist in vitro and in vivo in either the chlamydial ligand or their cognate host receptor(s) that functions in chlamydial adherence to epithelial cells. The latter possibility is supported in part by the recent work of Chen and Stephens (7), showing that chlamydial adherence to epithelial cells occurs through both glycosaminoglycan-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Thus, chlamydial adherence in vivo might be mediated through a glycosaminoglycan-independent mechanism(s) which would not be expected to be inhibited by heparin or DS-10,000. It is also possible that delivery methods that would provide a sustained concentration of inhibitory compounds at the genital tract mucosa would yield more favorable results than those reported here. Regardless, our findings emphasize the importance of testing candidate antichlamydial microbicides in in vivo models of chlamydial infection to more accurately assess their utility for the potential control of chlamydial STDs in humans.

FIG. 2.

Inhibitory activities of heparin and DS-10,000 on in vivo infectivity of C. trachomatis. Chlamydiae were incubated with heparin (A) or DS-10,000 (B) at 2 mg/ml, and the mixtures were then inoculated intravaginally into mice. (C) A 20-μl volume of heparin or DS-10,000 (100 mg/ml; 2 mg/mouse) was inoculated into the vaginal vault of each mouse, and the mice were then challenged intravaginally with chlamydiae.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the technical assistance of Bill Whitmire.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba M, Nakajima M, Schols D, Pauwels R, Balzarini J, De Clercq E. Pentosan polysulfate, a sulfated oligosaccharide, is a potent and selective anti-HIV agent in vitro. Antivir Res. 1988;9:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(88)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba M, Pauwels R, Balzarini J, Arnout J, Desmyter J, De Clercq E. Mechanism of inhibitory effect of dextran sulfate and heparin on replication of human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6132–6136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba M, Schols D, De Clercq E, Pauwels R, Nagy M, Gyorgyi-Edelenyi J, Low M, Gorog S. Novel sulfated polymers as highly potent and selective inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus replication and giant cell formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:134–138. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunham R C, Binns B, McDowell J, Paraskevas M. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women with ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:722–726. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198605000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunham R C, Maclean I W, Binns B, Peeling R W. Chlamydia trachomatis: its role in tubal infertility. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:1275–1282. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.6.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldwell H D, Kromhout J, Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J C-R, Stephens R S. Chlamydia trachomatis glycosaminoglycan-dependent and independent attachment to eukaryotic cells. Microb Pathog. 1997;22:23–30. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen T, Belland R J, Wilson J, Swanson J. Adherence of pilus− Opa+ gonococci to epithelial cells in vitro involves heparan sulfate. J Exp Med. 1995;182:511–517. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow J M, Yonekura M L, Richwald G A, Greenland S, Sweet R L, Schachter J. The association between Chlamydia trachomatis and ectopic pregnancy. JAMA. 1990;263:3164–3167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotter T W, Meng Q, Shen Z, Zhang Y, Su H, Caldwell H D. Protective efficacy of major outer membrane protein-specific immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG monoclonal antibodies in a murine model of Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4704–4714. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4704-4714.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito M, Baba M, Sato A, Pauwels R, De Clercq E, Shigeta S. Inhibitory effect of dextran sulfate and heparin on the replication of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in vitro. Antivir Res. 1987;7:361–367. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(87)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones R B, Ardery B R, Hui S L, Cleary R E. Correlation between serum antichlamydial antibodies and tubal factor as a cause of infertility. Fertil Steril. 1982;38:553–558. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)46634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitsuya H, Looney D J, Kuno S, Ueno R, Wong-Staal F, Border S. Dextran sulfate suppression of viruses in the HIV family: inhibition of virion binding to CD4+ cells. Science. 1988;240:646–649. doi: 10.1126/science.2452480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neyts J, De Clercq E. Effect of polyanionic compounds on intracutaneous and intravaginal herpesvirus infection in mice: impact on the search for vaginal microbicides with anti-HIV activity. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;10:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schachter J. Chlamydial infections. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:540–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197803092981005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schachter J. Overview of human diseases. In: Barron A L, editor. Microbiology of chlamydia. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1988. pp. 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su H, Caldwell H D. In vitro neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis by monovalent Fab antibody specific to the major outer membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2843–2845. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2843-2845.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su H, Caldwell H D. CD4+ T cells play a significant role in adoptive immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the mouse genital tract. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3302–3308. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3302-3308.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su H, Raymond L, Rockey D D, Fischer E, Hackstadt T, Caldwell H D. A recombinant Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein binds to heparan sulfate receptors on epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11143–11148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueno R, Kuno S. Dextran sulfate, a potent anti-HIV agent in vitro having synergism with zidovudine. Lancet. 1987;i:1379. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90681-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Putten J P M, Paul S M. Binding of syndecan-like cell surface proteoglycan receptors is required for Neisseria gonorrhoeae entry into human mucosal cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:2144–2154. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaretzky F R, Pearce-Pratt R, Phillips D M. Sulfated polyanions block Chlamydia trachomatis infection of cervix-derived human epithelia. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3520–3526. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3520-3526.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J P, Stephens R S. Mechanism of C. trachomatis attachment to eukaryotic host cells. Cell. 1992;69:861–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90296-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]