Abstract

Background:

The agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia (PAA), primary progressive apraxia of speech (PPAOS), or a combination of both (AOS+PAA) are neurodegenerative disorders characterized by speech-language impairments and together compose the AOS-PAA spectrum disorders. These patients typically have an underlying 4-repeat tauopathy, although they sometimes show evidence of beta-amyloid and tau deposition on PET, suggesting Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Given the growing number of pharmacologic treatment options for AD, it is important to better understand the incidence of AD pathology in these patients.

Objective:

This study aimed to evaluate the frequency of beta-amyloid and tau positivity in AOS-PAA spectrum disorders. Sixty-five patients with AOS-PAA underwent a clinical speech-language battery and PiB PET and flortaucipir PET imaging.

Method:

Global PiB PET standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) and flortaucipir PET SUVRs from the temporal meta region of interest were compared between patient groups. For 19 patients who had died and undergone autopsy, their PET and pathology findings were also compared.

Results:

The results showed that although roughly half of the patients are positive for at least one biomarker, their clinical symptoms and biomarker status were not related, suggesting that AD is not the primary cause of their neurodegeneration. All but one patient in the autopsy subset had a Braak stage of IV or less, despite four being positive on tau PET imaging.

Conclusion:

Inclusion criteria for clinical trials should specify clinical presentation or adjust the evaluation of such treatments to be specific to disease diagnosis beyond the presence of certain imaging biomarkers.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, biomarkers, tau protein, beta-amyloid protein

Introduction:

Primary progressive aphasia is a form of neurodegeneration that presents with language difficulties as the primary symptom. The agrammatic variant of PPA (PAA) often occurs concomitantly with progressive apraxia of speech (AOS+PAA), which is characterized by motor-speech difficulties, and may also occur in isolation from aphasia, in which case it is termed primary progressive AOS (PPAOS). These disorders are often grouped together as one form of neurodegeneration (i.e., non-fluent variant of PPA [1]), which we collectively refer to as AOS-PAA spectrum disorders.1 Patients with AOS-PAA spectrum disorders typically have one of the following underlying pathologies: corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, or Pick’s disease [2–5].

Beta-amyloid (Aβ) deposition on PET has been previously observed in these disorders [6–9]. This indicates a likely co-pathology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), despite patients not presenting with typical AD symptoms; although, these studies did not assess tau uptake on positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Given the growing number of pharmacologic treatment options for patients with AD, it is important to better understand the incidence of AD pathology in the AOS-PAA spectrum disorders, in which it is unlikely that AD is the driving pathology of the clinical symptoms [2–5]. The goal of the present study was, therefore, to examine the frequency of Aβ and tau deposition on PET in a large cohort of patients with clinically defined AOS-PAA spectrum disorder and determine if biomarker status affects clinical presentation. We hypothesized that Aβ and tau positivity would not be uncommon within AOS-PAA spectrum patients and that biomarker status would not affect clinical presentation.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty-five patients were recruited by the Neurodegenerative Research Group at Mayo Clinic to participate in an NIH-funded study investigating neurodegenerative speech and language disorders, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic. A diagnosis of either PAA (n=6), AOS+PAA (n=36), or PPAOS (n=23), all of which fall under the umbrella of AOS-PAA spectrum disorders, was given by consensus after clinical scores, writing samples, and video recordings of each patient were reviewed by at least two speech-language pathologists. Video recordings included a thorough speech-language evaluation by a speech-language pathologist that included the Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale (ASRS-3)[10, 11], the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB) [12], and the Boston Naming Test (BNT) [13], among other clinical tests, to assess the presence and severity of aphasia and apraxia of speech. Patients also were evaluated on conversational speech, narrative picture description, and supplementary motor speech tasks (vowel prolongation, speech alternating motion rates (e.g. rapid repetition of ‘puhpuhpuh’), speech sequential motion rates (e.g. rapid repetition of ‘puhtuhkuh’), and word and sentence repetition tasks). Memory was also assessed using the Camden Memory Test by a neuro-psychometrist, independent of the speech-language diagnosis [14].

All patients underwent a Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) PET scan to assess Aβ, as well as tau-PET scan using [18F]flortaucipir to assess tau uptake at the same visit. A global PiB standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) of ≥ 1.48 and a temporal lobe tau meta-ROI SUVR of ≥ 1.25 [15, 16] were used to determine Aβ and tau positivity, respectively.

Clinical profiles of AOS-PAA spectrum patients were compared across biomarker status groups; categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s Exact Tests, and continuous variables were analyzed using an Analysis of Variance, adjusting for age at the time of imaging where applicable.

Sixteen of the patients in the present study have died and undergone an autopsy. Standard neuropathological evaluations were performed by a neuropathologist (DWD) following current diagnostic protocols [17], and Braak stage [18] and Thal phase [19] were determined, as well as primary and secondary pathological diagnoses using published diagnostic criteria. All participants underwent apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping, as previously described [20].

Results:

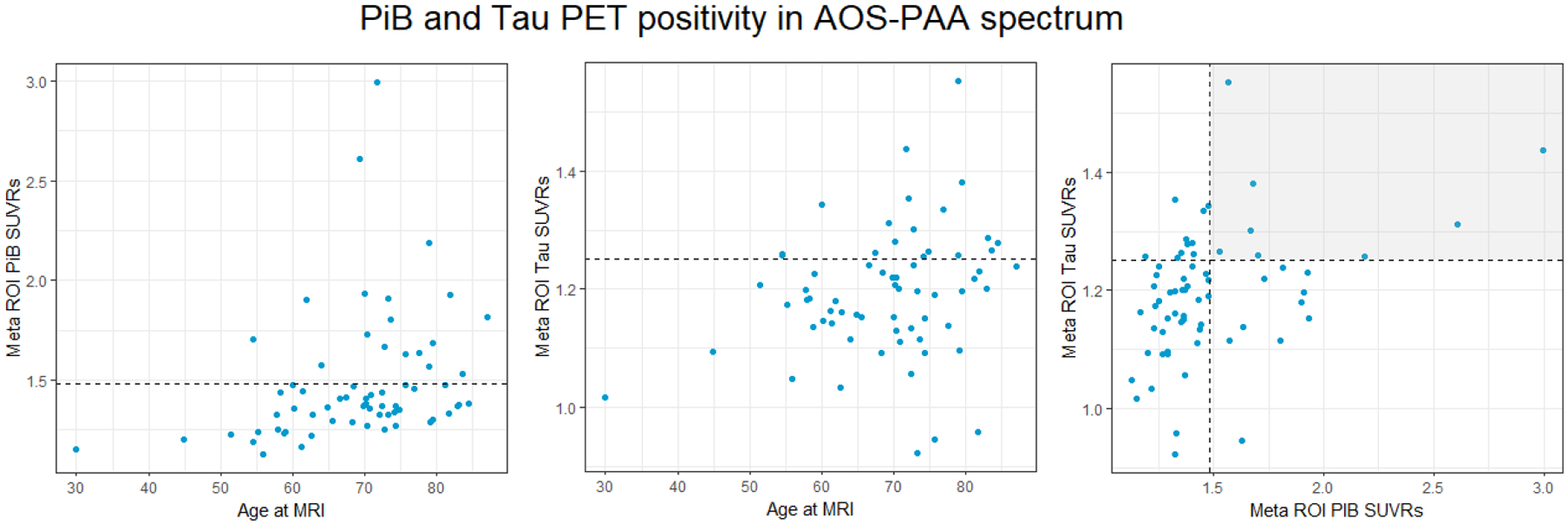

Eight patients (12%) were both Aβ and tau positive, suggesting underlying AD pathology. An additional ten patients (15%) were Aβ positive but tau negative, and ten others (15%) were tau positive but Aβ negative (Figure 1). Furthermore, Aβ SUVRs increased with age more so than tau SUVRs, and the two biomarkers were related to each other (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Plots of PiB and tau PET by age at imaging, and between PiB and tau SUVRs. The dashed lines show the threshold of what is considered PiB and tau positive for each imaging modality. Each point above the dotted line represents a patient who is positive on that imaging biomarker. In the third graph, each point within the shaded quadrant represents a patient who is positive on both PiB and tau PET biomarkers.

Figure 1. Plots of PiB and Tau PET by age at imaging, and between PiB and tau SUVRs. The dashed lines show the threshold of what is considered PiB and tau positive for each imaging modality. Each point above the dotted line represents a patient who is positive on that imaging biomarker. In the third graph, each point within the shaded quadrant represents a patient who is positive on both PiB and Tau PET biomarkers.

When comparing clinical characteristics by biomarker status, there were no significant differences among groups (Table 1). Those who were negative for both biomarkers tended to be younger than those who were positive on one or both biomarkers. Additionally, none of the participants who were Aβ-negative but tau-positive were APOE ε4 carriers.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics at baseline by biomarker status. Data shown are median (Q1, Q3), or n (%). For categorical variables, p-values are from Fisher’s Exact Test. For continuous variables, p-values are from Fit an Analysis of Variance adjusting for age at imaging where applicable.

| Aβ-, tau- (n=37) |

Aβ-, tau+ (n=10) |

Aβ+, tau- (n=10) |

Aβ+, tau+ (n=8) |

All AOS-PAA spectrum patients | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 68.26 (59.10, 72.88) | 73.12 (68.16, 76.44) | 73.5 (70.15, 77.17) | 75.93 (71.16, 79.19) | 70.45 (62.02, 75.69) | 0.06 |

| Female, n (%) | 18 (49%) | 6 (60%) | 6 (60%) | 4 (50%) | 34 (53%) | 0.84 |

| APOE ε4 carrier, n (%) | 12 (32%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (31%) | 4 (50%) | 18 (28%) | 0.84 |

| ASRS-3 total | 17 (12, 24.5) | 18 (11, 29) | 18 (12, 25) | 22.5 (14.75, 24) | 18 (12, 25) | 0.94 |

| WAB-AQ | 93.3 (82.45, 97.3) | 85.50 (78.30, 98.0) | 96.30 (91.50, 98.40) | 94.90 (92.62, 97.88) | 93.5 (83.9, 97.8) | 0.33 |

| BNT | 13 (12, 15) | 13 (11, 15) | 14 (12.5, 14.75) | 14 (13.5, 15) | 14 (12, 15) | 0.45 |

| Camden words total score | 24 (22, 25) | 24 (24, 24.75) | 25 (24, 25) | 24 (18.5, 24) | 24 (23, 25) | 0.25 |

| PiB-PET SUVRs | 1.32 (1.25, 1.37) | 1.38 (1.34, 1.41) | 1.81 (1.66, 1.91) | 1.69 (1.64, 2.29) | 1.37 (1.29, 1.57) | <0.0001 |

| Flortaucipir SUVRs | 1.16 (1.10, 1.20) | 1.28 (1.26, 1.32) | 1.17 (1.12, 1.21) | 1.31 (1.26, 1.39) | 1.20 (1.14, 1.26) | <0.0001 |

Data are shown as Median (Q1, Q3). * Value is different from other clinical groups (p < 0.001).

Note: ASRS-3, Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale-Version 3; WAB AQ, Western Aphasia Battery-Revised Aphasia Quotient; BNT, Boston Naming Test

Nineteen of the patients in this study underwent autopsy, and their pathology findings are shown in the data in Table 2. The most common primary pathologies were progressive supranuclear palsy (n=8) and corticobasal degeneration (n=6), with two cases having FTLD with TDP-43 inclusions, one having Pick’s Disease, one having globular glial tauopathy, and one having unspecified 3R-4R frontotemporal tauopathy. The Braak stages ranged from I-V with a median of III and Thal phase ranging from 0–3; the National Institute on Aging – Alzheimer’s Association AD levels [21] are also reported in Table 2 and reflect the likelihood of AD co-pathology. We did not see any relationship between the tau-PET SUVR and Braak stage, with the three patients who were positive on tau-PET having Braak stages of I-II, while 11 who were negative for tau-PET had Braak stages of III-V at death. All six patients that were Aβ-PET positive had Aβ deposition at autopsy, with Thal phase of 3 in four patients and Thal phase of 1/2 in the other two patients. None of these six patients were tau-PET positive. Of the 13 patients that were Aβ-PET negative, five had evidence for Aβ deposition at autopsy.

Table 2.

PET and pathology findings for nineteen patients

| Patient | Age at death | PiB | Tau | Years between scan - death | Primary pathology | NIA-AA AD level | Braak stage | Thal phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73.7 | 1.73 | 1.22 | 1.3 | PSP | Int | IV | A2 (Thal 3) |

| 2 | 52.9 | 1.23 | 1.21 | 1.5 | CBD | Not | IV | A0 |

| 3 | 77.8 | 1.27 | 1.09 | 3.4 | PSP | Not | I | A0 |

| 4 | 68.4 | 1.41 | 1.26 | 0.9 | CBD | Not | II | A0 |

| 5 | 92.7 | 1.81 | 1.24 | 5.6 | CBD | Low-int | IV | A1 (Thal 1/2) |

| 6 | 59.6 | 1.23 | 1.14 | 0.8 | CBD | Not | IV | A0 |

| 7 | 84.6 | 1.93 | 1.23 | 2.6 | PSP | Low-int | III-IV | A1 (Thal 1/2) |

| 8 | 78.1 | 1.67 | 1.3 | 5.3 | PSP | Int | IV-V | A2 (Thal 3) |

| 9 | 72.3 | 1.37 | 1.22 | 2.5 | PSP | Unknown | III | unknown |

| 10 | 60.0 | 1.43 | 1.18 | 1.7 | FTLD-TDP1 | Low-int | III | A1 (Thal 1/2) |

| 11 | 57.5 | 1.19 | 1.26 | 2.9 | FTLD-TDP1 | Not | I | A0 |

| 12 | 64 | 1.36 | 1.15 | 4.8 | Pick’s Disease | Low | IV-V | A1 (Thal 1/2) |

| 13 | 61 | 1.32 | 1.20 | 2.4 | CBD | Int | IV-V | A1 (Thal 1/2) |

| 14 | 64 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 2.2 | Mixed 3R-4R frontotemporal tauopathy | Not | I | A0 |

| 15 | 87.1 | 1.37 | 1.29 | 4 | GGT type1 | Low | II | A2 (Thal 3) |

| 16 | 77.8 | 1.8 | 1.11 | 4 | PSP | Low | II | A2 (Thal 3) |

| 17 | 83.7 | 1.34 | 1.2 | 0.8 | PSP | Not | III | A0 |

| 18 | 86.7 | 1.33 | 0.96 | 4.9 | PSP | Int | IV | A2 (Thal 3) |

| 19 | 74 | 1.93 | 1.15 | 3.9 | CBD | Low | II | A2 (Thal 3) |

These patients with FTLD-TDP also had genetic progranulin mutations, as well as executive dysfunction and mild behavioral changes [3].

PiB – Pittsburgh Compound B, NIA-AA – National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association, PSP – progressive supranuclear palsy, CBD – corticobasal degeneration, FTLD-TDP – frontotemporal lobar degeneration tar DNA binding protein 43, GGT – globular glial pathology

Discussion:

The results of this study show that Aβ and tau positivity is not uncommon in patients whose disease falls within the AOS-PAA spectrum, with 42% showing positivity in at least one AD biomarker. When comparing the patients in this study by biomarker status, there were no significant differences in clinical presentation. The interpretation of the positive AD biomarkers in this cohort is uncertain. Biomarkers did not appear to influence the clinical presentation, as there were no differences on tests of AOS, aphasia, or memory when comparing patients by tau and Aβ status at the group level. As we have previously shown [5], and as is clear in this study, these patients do not typically have AD as a primary pathology, and instead most commonly have a 4R tauopathy. Typical AD PiB and tau SUVRS tend to be much higher than those observed in our cohort: for example, the PiB SUVR range in typical AD has been previously reported as 1.80–4.66, and the tau SUVR range in typical AD, 1.3–3.27 [22]. These values are much higher than what was observed in our AOS-PAA spectrum cohort. That said, concomitant low-intermediate levels of AD pathology can be observed. Aβ-PET has a specificity of 100% but sensitivity of 50% in detecting diffuse Aβ plaques in patients with 4R tauopathies [23], and we observed similar results in our somewhat overlapping autopsy cohort. Hence, we can be relatively confident that Aβ deposition is present in the brains of the Aβ-PET positive patients. However, the utility of tau-PET to detect AD-type tau in these patients is more questionable, with Braak stages of IV or below generally undetectable by tau-PET in 4R tauopathies [23].

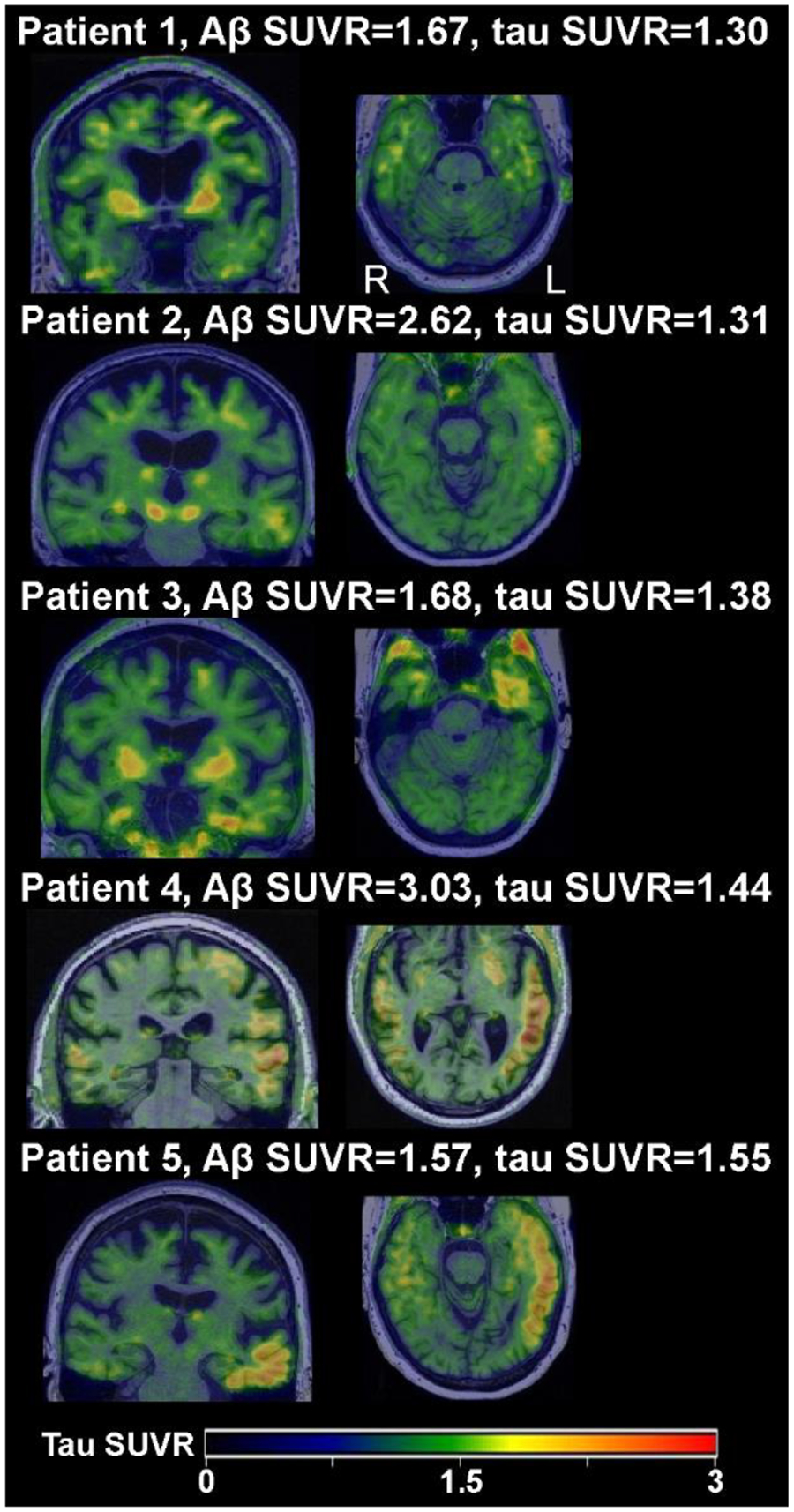

Similarly, in our autopsy subset, none of the patients with Braak IV showed positive tau-PET. These patients also rarely have AD co-pathology with a Braak stage greater than IV. Therefore, in most of our tau-PET positive patients it is likely that the elevated uptake reflects measurement variability, off-target binding, or inflammation, as some possibilities. Further, many of the tau PET values were only just above the cut-point, reflecting borderline scores. A higher tau SUVR cut-off of 1.29 [24] is likely more specific for the presence, or clinical meaningfulness, of AD pathology. Only five of the 65 total patients in the present study showed convincingly high tau above this 1.29 threshold and positive Aβ-PET values, shown in Figure 2; thus, it is still possible that we are detecting the presence of concomitant intermediate-high likelihood AD in these cases, although autopsy evaluations of these patients will be needed to verify. It should be noted that patient 4 in Figure 2 had a high PiB SUVR as well (2.99) but also had a different clinical presentation. While his overall clinical presentation was consistent with AOS-PAA spectrum, he also had some features of the logopenic variant of PPA, including phonological errors and impaired word retrieval, which is most commonly associated with underlying AD pathology; he also reported a family history of early onset AD. Thus, he may be a unique case in which AD co-pathology is driving some of his symptoms.

Figure 2.

Tau-PET scans of patients whose temporal meta-ROI exceeded the 1.29 SUVR threshold.

In the present study, only uptake in the temporal meta-ROI was used in determining tau positivity on PET imaging, as this is the region most typically associated with AD dementia [18]. However, tau accumulation often corresponds to regional cortical atrophy [25–27], which for AOS-PAA spectrum disorder patients is typically in the inferior frontal and premotor cortices more so than in temporal regions in earlier stages of the disease [28–30]. It is possible that the patients who were tau-negative in the temporal meta-ROI may show increased uptake of both non-AD-type and AD-type tau in other cortical regions that correspond better to their clinical presentations [31]. The pathological findings in the autopsy subset revealed that patients who were negative on tau-PET imaging often had Braak stages of III or higher when looking at the whole brain.

A limitation of this study is that we were unable to compare the PiB and tau PET SUVRs within AOS-PAA spectrum disorder patients with an age-matched cohort of patients with typical AD; this was due to the fact that patients with typical AD do not undergo the same clinical battery as those with AOS-PAA spectrum disorder.

These findings are particularly important because the increasing number of targeted pharmacological options and ongoing clinical trials set enrollment criteria based on Aβ and/or tau PET positivity. As such, many patients with AOS-PAA spectrum disorders meet enrollment criteria, despite these clinical trials being aimed at patients with primary AD pathology. However, it is unlikely that these treatments will benefit these patients since their symptom-driving pathology is not AD. Including these patients may be problematic because clinical trial outcomes are often targeted to features of typical amnestic AD. Therefore, these targeted clinical trials should not only consider the biological variables but also clinical presentations. Alternatively, if patients without primary (or even atypical) AD are enrolled due to the presence of these AD biomarkers, the outcome measures should reflect the clinical impairments (i.e., change in speech/language impairments in AOS-PAA spectrum disorder patients). We plan to evaluate the significance of these biomarkers in the future in a larger autopsy-validated cohort.

Acknowledgements:

The authors have no acknowledgments to report.

Funding:

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders grants R01-DC010367 awarded to Keith A. Josephs, R01-DC14942 awarded to Keith A. Josephs and Rene L. Utianski, and R01-DC012519 awarded to Jennifer L. Whitwell.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Jennifer L. Whitwell is a Board Member of this journal but was not involved in the peer-review process nor had access to any information regarding its peer-review.

We avoid the use of the term nonfluent variant of PPA because we do not feel that patients with isolated PPAOS should be termed as having aphasia, when aphasia is, by definition, absent. Hence, we use “AOS-PAA spectrum disorder” to characterize these syndromes.

Data Availability:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, Ogar JM, Rohrer JD, Black S, Boeve BF, Manes F, Dronkers NF, Vandenberghe R, Rascovsky K, Patterson K, Miller BL, Knopman DS, Hodges JR, Mesulam MM, Grossman M (2011) Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76, 1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Whitwell JL, Layton KF, Parisi JE, Hauser MF, Witte RJ, Boeve BF, Knopman DS (2006) Clinicopathological and imaging correlates of progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Brain 129, 1385–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chare L, Hodges JR, Leyton CE, McGinley C, Tan RH, Kril JJ, Halliday GM (2014) New criteria for frontotemporal dementia syndromes: clinical and pathological diagnostic implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85, 865–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Harris JM, Gall C, Thompson JC, Richardson AM, Neary D, du Plessis D, Pal P, Mann DM, Snowden JS, Jones M (2013) Classification and pathology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 81, 1832–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Utianski RL, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Botha H, Martin PR, Pham NTT, Stierwalt J (2021) A molecular pathology, neurobiology, biochemical, genetic and neuroimaging study of progressive apraxia of speech. Nature communications 12, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Leyton CE, Villemagne VL, Savage S, Pike KE, Ballard KJ, Piguet O, Burrell JR, Rowe CC, Hodges JR (2011) Subtypes of progressive aphasia: application of the International Consensus Criteria and validation using β-amyloid imaging. Brain 134, 3030–3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Santos-Santos MA, Rabinovici GD, Iaccarino L, Ayakta N, Tammewar G, Lobach I, Henry ML, Hubbard I, Mandelli ML, Spinelli E, Miller ZA, Pressman PS, O’Neil JP, Ghosh P, Lazaris A, Meyer M, Watson C, Yoon SJ, Rosen HJ, Grinberg L, Seeley WW, Miller BL, Jagust WJ, Gorno-Tempini ML (2018) Rates of Amyloid Imaging Positivity in Patients With Primary Progressive Aphasia. JAMA Neurol 75, 342–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Whitwell JL (2014) APOE ε4 influences β-amyloid deposition in primary progressive aphasia and speech apraxia. Alzheimers Dement 10, 630–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Josephs KA (2016) Clinical and MRI models predicting amyloid deposition in progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Neuroimage Clin 11, 90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Duffy JR, Martin PR, Clark HM, Utianski RL, Strand EA, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA (2023) The Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale: Reliability, Validity, and Utility. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 32, 469–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Strand EA, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Josephs KA (2014) The Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale: A tool for diagnosis and description of apraxia of speech. Journal of communication disorders 51, 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kertesz A (2007) Western Aphasia Battery--Revised. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lansing AE, Ivnik RJ, Cullum CM, Randolph C (1999) An empirically derived short form of the Boston naming test. Archives of clinical neuropsychology 14, 481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Warrington EK (1996) The Camden memory tests manual, Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jack CR Jr., Therneau TM, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, Lowe VJ, Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Machulda MM, Graff-Radford J, Jones DT, Schwarz CG, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Rocca WA, Petersen RC (2019) Prevalence of Biologically vs Clinically Defined Alzheimer Spectrum Entities Using the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Research Framework. JAMA Neurol 76, 1174–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jack CR Jr., Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Jones DT, Kantarci K, Machulda MM, Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Vemuri P, Reyes DA, Petersen RC (2017) Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 13, 205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L (1991) The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 41, 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82, 239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H (2002) Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 58, 1791–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Josephs KA, Tsuboi Y, Cookson N, Watt H, Dickson DW (2004) Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 is a determinant for Alzheimer-type pathologic features in tauopathies, synucleinopathies, and frontotemporal degeneration. Arch Neurol 61, 1579–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS, Nelson PT, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Thies B, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Montine TJ (2012) National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 8, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lowe VJ, Lundt ES, Albertson SM, Min HK, Fang P, Przybelski SA, Senjem ML, Schwarz CG, Kantarci K, Boeve B, Jones DT, Reichard RR, Tranovich JF, Hanna Al-Shaikh FS, Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr., Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Murray ME (2020) Tau-positron emission tomography correlates with neuropathology findings. Alzheimers Dement 16, 561–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ghirelli A, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Clark HM, Ali F, Botha H, Duffy JR, Utianski RL, Buciuc M, Murray ME, Labuzan SA, Spychalla AJ, Pham NTT, Schwarz CG, Senjem ML, Machulda MM, Baker M, Rademakers R, Filippi M, Jack CR Jr., Lowe VJ, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Josephs KA, Whitwell JL (2020) Sensitivity-Specificity of Tau and Amyloid β Positron Emission Tomography in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Ann Neurol 88, 1009–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lowe VJ, Curran G, Fang P, Liesinger AM, Josephs KA, Parisi JE, Kantarci K, Boeve BF, Pandey MK, Bruinsma T, Knopman DS, Jones DT, Petrucelli L, Cook CN, Graff-Radford NR, Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr., Murray ME (2016) An autoradiographic evaluation of AV-1451 Tau PET in dementia. Acta Neuropathol Commun 4, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Iaccarino L, Tammewar G, Ayakta N, Baker SL, Bejanin A, Boxer AL, Gorno-Tempini ML, Janabi M, Kramer JH, Lazaris A, Lockhart SN, Miller BL, Miller ZA, O’Neil JP, Ossenkoppele R, Rosen HJ, Schonhaut DR, Jagust WJ, Rabinovici GD (2018) Local and distant relationships between amyloid, tau and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuroimage Clin 17, 452–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sintini I, Schwarz CG, Martin PR, Graff-Radford J, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Reid RI, Spychalla AJ, Drubach DA, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Josephs KA, Whitwell JL (2019) Regional multimodal relationships between tau, hypometabolism, atrophy, and fractional anisotropy in atypical Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 40, 1618–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Whitwell JL, Graff-Radford J, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Spychalla AJ, Vemuri P, Jones DT, Drubach DA, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Ertekin-Taner N, Petersen RC, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Josephs KA (2018) Imaging correlations of tau, amyloid, metabolism, and atrophy in typical and atypical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14, 1005–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Whitwell JL (2013) Syndromes dominated by apraxia of speech show distinct characteristics from agrammatic PPA. Neurology 81, 337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Master AV, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr, Whitwell JL (2012) Characterizing a neurodegenerative syndrome: primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain 135, 1522–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tetzloff KA, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Utianski RL, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Botha H, Martin PR, Schwarz CG, Senjem ML (2019) Progressive agrammatic aphasia without apraxia of speech as a distinct syndrome. Brain 142, 2466–2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Utianski RL, Whitwell JL, Schwarz CG, Senjem ML, Tosakulwong N, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Machulda MM, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr., Lowe VJ, Josephs KA (2018) Tau-PET imaging with [18F]AV-1451 in primary progressive apraxia of speech. Cortex 99, 358–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.