Abstract

The T-cell response to fibronectin attachment protein (FAP-A) in BALB/c and B10.BR mice was examined. Both strains developed strong T-cell responses to FAP-A, directed to single, unique epitopes. T cells from mice infected with Mycobacterium avium responded to FAP-A, suggesting a possible role in a protective immune response.

Mycobacterium avium is a common source of disseminated bacterial infection in patients with AIDS (4, 5). T cells play a central role in the development of protective immunity to M. avium (1, 6–8, 10, 12), but few antigens of M. avium have been cloned and characterized (11, 16, 19, 22), and nothing is known about which antigens of M. avium stimulate protective immune responses. We have recently identified a family of mycobacterial proteins termed fibronectin attachment proteins (FAPs) and have characterized their role in the uptake of mycobacteria into cells (14, 19, 20). We also have cloned the M. avium cognate of FAP, FAP-A, and have identified two sites within the molecule which bind to fibronectin. These two sites are highly conserved between FAP-A, FAP-L, and the recently cloned apa-encoded protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (FAP-TB) (9, 19). Intriguingly, the amino acid sequences of the cloned FAPs revealed that they are closely related to a family of proteins which are rich in proline and alanine residues and which have been demonstrated to play a role in immune responses to several mycobacterial species (3, 9, 15, 17, 21). Most intriguing, immune responses in guinea pigs to the 45/47-kDa complex of Mycobacterium bovis BCG (FAP-BCG) were observed by Marchal and colleagues only when the guinea pigs were inoculated with live, but not heat-killed, M. bovis BCG, an immunization protocol which has been shown to be most effective at eliciting protective immunity (15). In addition, our studies of the function of FAP suggested that an immune response directed against this protein might protect against M. avium infection. We therefore set out to study the role that FAP-A plays in murine immune responses to M. avium.

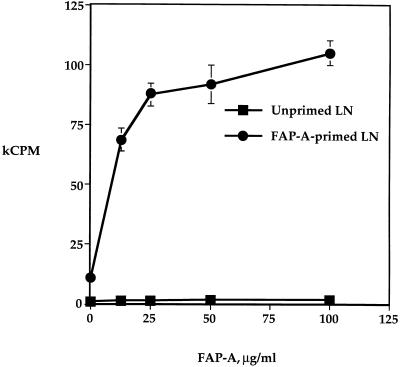

To generate large quantities of FAP-A, we expressed it as a recombinant protein in Escherichia coli by use of the pTrcHis vector and purified it to homogeneity with a nickel column followed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. We used two FAP-A fusion proteins, FAP-A(1-381), comprising the entire amino acid sequence of the protein, and FAP-A(136-381). To determine first whether rFAP-A is immunogenic in mice, BALB/c (H-2d) mice were immunized with rFAP-A(1-381) emulsified in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA). Lymph node (LN) cells from mice primed with rFAP-A mounted a vigorous proliferative response to the immunogen (Fig. 1). In contrast, LN cells from naive mice failed to respond. We also detected a strong T-cell proliferative response to FAP-A in B10.BR mice (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Recombinant FAP-A is immunogenic in mice. BALB/c (H-2d) mice were immunized with 50 μg of FAP-A(1-381) in IFA subcutaneously. One week later, LN cells from FAP-A-immunized or unimmunized control mice were cultured with increasing doses of FAP-A(1-381). The cultures were pulsed with [3H]thymidine 3 days after the initiation of culture and harvested for scintillation counting 1 day later. Error bars indicate the ranges of duplicate cultures.

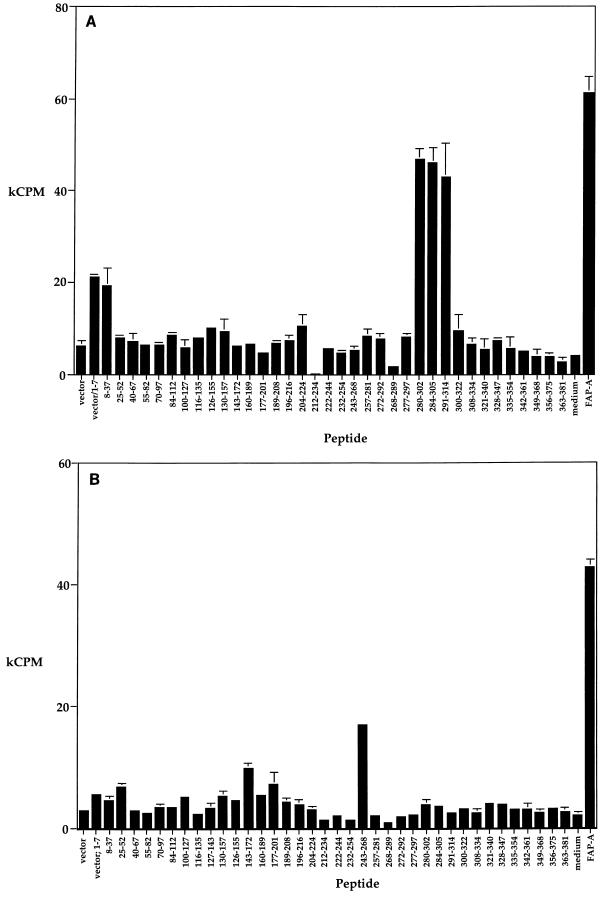

To identify the T-cell epitopes of the FAP-A molecule recognized by BALB/c (H-2d) and B10.BR (H-2k) mice, we employed a panel of 38 synthetic peptides varying from 18 to 30 amino acids in length, which spanned the entire sequence of FAP-A (13, 18). BALB/c mice were immunized with FAP-A(1-381) emulsified in IFA. One week later, LN cells were stimulated with each peptide of the panel as described elsewhere (23). Three peptides spanning the region of amino acids 280 to 314 specifically stimulated the FAP-A-primed LN cells (Fig. 2A). Thus, in BALB/c mice, the T-cell immune response is directed to a single region of the molecule comprising amino acids 280 to 314. A similar experiment was performed with B10.BR mice (Fig. 2B). FAP-A-primed B10.BR mice mounted a specific, vigorous proliferative response to a peptide comprising amino acids 243 to 268. Thus, as with BALB/c mice, the predominant T-cell response of B10.BR mice to FAP-A is directed against a single but distinct region of the molecule. Interestingly, these two regions, like the fibronectin-binding domains, are located in the most highly conserved region of the FAP molecule, which contains few alanine and proline residues (19).

FIG. 2.

Identification of T-cell epitopes of FAP-A. BALB/c (A) or B10.BR (B) mice were immunized with FAP-A(1-381) emulsified in IFA subcutaneously. Seven (A) or nine (B) days later, draining LN cells were cultured alone (medium control), with FAP-A(1-381) at 100 μg/ml, or with peptides whose sequences comprised the indicated amino acids of FAP-A (10 μM). The cultures were pulsed with [3H]thymidine 3 days after the initiation of culture and harvested for scintillation counting 1 day later. Error bars indicate the ranges of duplicate cultures.

To further define the T-cell epitope of FAP-A recognized by BALB/c mice, we synthesized a peptide comprising amino acids 288 to 302 to accommodate a putative 13-amino-acid epitope containing an I-Ad binding motif. BALB/c mice were immunized with the FAP-A(136-381) fusion protein, and LN cells were tested for their response to the FAP-A(288-302) peptide. The LN cells mounted a strong proliferative response to the peptide. This proliferative response was also inhibited by a monoclonal antibody specific for I-Ad (data not shown). These data thus indicate that the minimal epitope of FAP-A recognized by BALB/c mice is FAP-A(288-302)/I-Ad. We performed a similar analysis to define the epitope recognized by B10.BR mice. We identified the epitope recognized by B10.BR mice as FAP-A(249-262)/I-Ak.

M. bovis BCG has been employed as a vaccine to protect against M. tuberculosis infection. The vaccine’s efficacy is based upon the fact that T cells primed against M. bovis BCG cross-react with cognate antigens of similar sequence from M. tuberculosis. An alignment of the amino acid sequences of FAP-A, FAP-TB, and FAP-L revealed that the three proteins have regions of high homology (19). We tested whether T cells primed to FAP-A would cross-react with FAP-TB and FAP-L. B10.BR mice were immunized with FAP-A(136-381), and the primed LN cells were tested for their responses to the FAP-A(249-262) peptide as well as to peptides whose sequences were derived from the homologous regions of FAP-TB/BCG and FAP-L (the FAP sequence is identical between M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG). As observed above, LN cells from FAP-A-primed B10.BR mice proliferated vigorously in response to the FAP-A(249-262) peptide (Fig. 3A). These cells also gave a strong response to a peptide comprising the cognate region of FAP-TB. There was no significant response to a peptide with amino acid sequences derived from FAP-L, however. A similar experiment was performed with BALB/c mice (Fig. 3B). LN cells from FAP-A-primed mice responded vigorously to the immunodominant FAP-A(288-302) peptide, whereas there was no response to peptide with amino acid sequences derived from FAP-TB or FAP-L. Thus, for BALB/c mice, T cells primed to FAP-A are not cross-reactive to FAPs of other mycobacterial species, whereas for B10.BR mice, T cells primed to FAP-A cross-react with FAP-TB.

FIG. 3.

T cells primed to FAP-A have limited cross-reactivity to FAPs of other mycobacterial species. B10.BR (A) or BALB/c (B) mice were immunized with 50 μg of FAP-A(136-381) emulsified in IFA. Eight days later, draining LN cells were cultured either in medium alone, with FAP-A(136-381) at 100 μg/ml, or with the indicated FAP peptides (10 μM). The amino acid sequences of the peptides are indicated, as are the mycobacterial species from which the FAP sequences were derived. Dashes indicate identity with the FAP-A sequence. The cultures were pulsed with [3H]thymidine 3 days after the initiation of culture and harvested for scintillation counting 1 day later. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of triplicate cultures.

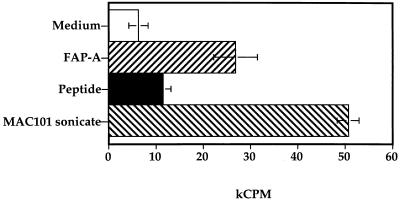

To determine whether an immune response to FAP-A occurred during infection, we tested whether LN cells from mice infected with live M. avium (2) would proliferate in response to FAP-A. One week after infection of BALB/c mice with M. avium, LN cells were incubated with the FAP-A(1-381) fusion protein or with the peptide FAP-A(288-302), which contains the immunodominant epitope of FAP-A in BALB/c mice. LN cells from the infected mice gave a strong proliferative response to FAP-A(1-381) (Fig. 4). The T cells also significantly responded to the FAP-A(288-302) peptide (P < 0.05; Student’s t test). Similarly, LN cells from infected B10.BR mice responded to the FAP-A(249-262) peptide (data not shown). These findings confirmed that the FAP-A(288-302) epitope is presented in vivo but that other FAP-A epitopes also are recognized during infection. Overall, these data indicate that T cells are stimulated by a FAP-A molecule during an infection with live M. avium and suggest that FAP-A could in part contribute to the development of protective T-cell immunity to M. avium. The sequence of FAP-A reveals that 40% of the amino acids are either proline or alanine. The amino- and carboxy-terminal portions of the protein are particularly rich in these residues. The prolines would hinder efficient antigen processing and presentation because of their inaccessibility to many proteolytic enzymes. The immunodominant epitopes defined for the two strains of mice are located in a region of FAP-A which is relatively poor in proline and alanine residues (19).

FIG. 4.

LN cells of mice infected with live M. avium proliferate in response to FAP-A. BALB/c mice were infected with 108 CFU of M. avium MAC101 subcutaneously. One week later, draining LN cells were cultured in medium alone, with 200 μg of FAP-A(1-381) per ml, with a peptide comprising residues 288 to 302 of FAP-A (1 μM), or with a sonicate of M. avium MAC101 (25 μg/ml). The cultures were pulsed with [3H]thymidine 3 days after the initiation of culture and harvested for scintillation counting 1 day later. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of triplicate cultures.

Taken together with earlier studies of the role of FAPs in immune responses to mycobacteria, our data suggest that the processing and presentation of FAP-A by M. avium-infected macrophages to T cells may contribute to the development of protective immunity to this pathogen. However, given that FAP is likely to be involved in the uptake of mycobacteria into epithelial cells, it will be of interest to direct anti-FAP immune responses to the intestinal mucosa. Nevertheless, the information obtained from analyzing immune responses to individual proteins such as FAP-A could serve as the basis for designing subunit vaccines which employ a collection of antigens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 5 PO1 AI33348.

We thank David Donermeyer, Daniel Kopp, and Bowdoin Su for technical assistance; Lowell Young for supplying M. avium MAC101; the Washington University Mass Spectrometry Resource for peptide analysis; and David Russell for helpful discussions. We thank Jerri Smith for her assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelberg R, Pedrosa J. Induction and expression of protective T cells during Mycobacterium avium infections in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;87:379–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb03006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermudez L E, Young L S. Tumor necrosis factor, alone or in combination with IL-2, but not IFNγ associated with macrophage killing of Mycobacterium avium complex. J Immunol. 1988;140:3006–3013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espitia C, Espinosa R, Saavedra R, Mancilla R, Romain F, Laqueyrerie A, Moreno C. Antigenic and structural similarities between Mycobacterium tuberculosis 50- to 55-kilodalton and Mycobacterium bovis BCG 45- to 47-kilodalton antigens. Infect Immun. 1995;63:580–584. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.580-584.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horsburgh C R., Jr Mycobacterium avium complex infection in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1332–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105093241906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horsburgh C R, Jr, Selik R M. The epidemiology of disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:4–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubbard R D, Flory C M, Collins F M. Memory T cell-mediated resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in innately susceptible and resistant mice. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2012–2016. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2012-2016.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubbard R D, Flory C M, Collins F M. T-cell immune responses in Mycobacterium avium-infected mice. Infect Immun. 1992;60:150–153. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.150-153.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ladel C H, Blum C, Dreher A, Reifenberg K, Kaufmann S H E. Protective role of γ/δ T cells and α/β T cells in tuberculosis. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2877–2881. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laqueyrerie A, Militzer P, Romain F, Eiglmeier K, Cole S, Marchal G. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the apa gene coding for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 45/47-kilodalton secreted antigen complex. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4003–4010. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4003-4010.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller I, Cobbold S P, Waldmann H, Kaufmann S H E. Impaired resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection after selective in vivo depletion of L3T4+ and Lyt-2+ T cells. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2037–2041. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2037-2041.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohara N, Matsuo K, Yamaguchi R, Yamazaki A, Tasaka H, Yamada T. Cloning and sequencing of the gene for α antigen from Mycobacterium avium and mapping of B-cell epitopes. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1173–1179. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1173-1179.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orme I M. The kinetics of emergence and loss of mediator T lymphocytes acquired in response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1987;138:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rammensee H-G. Chemistry of peptides associated with MHC class I and class II molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ratliff T L, McCarthy R, Telle W B, Brown E J. Purification of a mycobacterial adhesin for fibronectin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1889–1894. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1889-1894.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romain F, Laqueyrerie A, Militzer P, Pescher P, Chavarot P, Lagranderie M, Auregan G, Gheorghiu M, Marchal G. Identification of a Mycobacterium bovis BCG 45/47-kilodalton antigen complex, an immunodominant target for antibody response after immunization with living bacteria. Infect Immun. 1993;61:742–750. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.742-750.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouse D A, Morris S L, Karpas A B, Mackall J C, Probst P G, Chaparas S D. Immunological characterization of recombinant antigens isolated from a Mycobacterium avium λgt11 expression library by using monoclonal antibody probes. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2595–2600. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2595-2600.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sathish M, Esser R E, Thole J E R, Clark-Curtiss J E. Identification and characterization of antigenic determinants of Mycobacterium leprae that react with antibodies in sera of leprosy patients. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1327–1336. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1327-1336.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schild H, Grüneberg U, Pougialis G, Wallny H-J, Keilholz W, Stevanovic S, Rammensee H-G. Natural ligand motifs of H-2E molecules are allele specific and illustrate homology to HLA-DR molecules. Int Immunol. 1995;7:1957–1965. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.12.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schorey J S, Holsti M A, Ratliff T L, Allen P M, Brown E J. Characterization of the fibronectin-attachment protein of Mycobacterium avium reveals a fibronectin-binding motif conserved among mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:321–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6381353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schorey J S, Li Q, McCourt D W, Bong-Mastek M, Clark-Curtiss J E, Ratliff T L, Brown E J. A Mycobacterium leprae gene encoding a fibronectin binding protein is used for efficient invasion of epithelial cells and Schwann cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2652–2657. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2652-2657.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wieles B, van Agterveld M, Janson A, Clark-Curtiss J, De Wit T R, Harboe M, Thole J. Characterization of a Mycobacterium leprae antigen related to the secreted Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein MPT32. Infect Immun. 1994;62:252–258. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.252-258.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi R, Matsuo K, Yamazaki A, Takahashi M, Fukasawa Y, Wada M, Abe C. Cloning and expression of the gene for the Avi-3 antigen of Mycobacterium avium and mapping of its epitopes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1210–1216. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1210-1216.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yule T D, Basten A, Allen P M. Hen egg-white lysozyme-specific T cells elicited in hen egg-white lysozyme-transgenic mice retain an imprint of self-tolerance. J Immunol. 1993;151:3057–3069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]