Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The authors’ laboratory has previously demonstrated beneficial effects of noninvasive low intensity focused ultrasound (liFUS), targeted at the dorsal root ganglion (DRG), for reducing allodynia in rodent neuropathic pain models. However, in rats the DRG is 5 mm below the skin when approached laterally, while in humans the DRG is typically 5–8 cm deep. Here, using a modified liFUS probe, the authors demonstrated the feasibility of using external liFUS for modulation of antinociceptive responses in neuropathic swine.

METHODS

Two cohorts of swine underwent a common peroneal nerve injury (CPNI) to induce neuropathic pain. In the first cohort, pigs (14 kg) were iteratively tested to determine treatment parameters. liFUS penetration to the L5 DRG was verified by using a thermocouple to monitor tissue temperature changes and by measuring nerve conduction velocity (NCV) at the corresponding common peroneal nerve (CPN). Pain behaviors were monitored before and after treatment. DRG was evaluated for tissue damage postmortem. Based on data from the first cohort, a treatment algorithm was developed, parameter predictions were verified, and neuropathic pain was significantly modified in a second cohort of larger swine (20 kg).

RESULTS

The authors performed a dose-response curve analysis in 14-kg CPNI swine. Specifically, after confirming that the liFUS probe could reach 5 cm in ex vivo tissue experiments, the authors tested liFUS in 14-kg CPNI swine. The mean ± SEM DRG depth was 3.79 ± 0.09 cm in this initial cohort. The parameters were determined and then extrapolated to larger animals (20 kg), and predictions were verified. Tissue temperature elevations at the treatment site did not exceed 2°C, and the expected increases in the CPN NCV were observed. liFUS treatment eliminated pain guarding in all animals for the duration of follow-up (up to 1 month) and improved allodynia for 5 days postprocedure. No evidence of histological damage was seen using Fluoro-Jade and H&E staining.

CONCLUSIONS

The results demonstrate that a 5-cm depth can be reached with external liFUS and alters pain behavior and allodynia in a large-animal model of neuropathic pain.

Keywords: noninvasive modulatory ultrasound, preclinical, pigs, peripheral nerve, pain

Chronic pain affects 20.4% of the world’s population.1 Neuromodulatory techniques such as spinal cord stimulation (SCS) and dorsal root ganglion (DRG) stimulation are utilized for the treatment of medically refractory pain and account for more than 100,000 procedures annually worldwide.2 DRG stimulation is more effective than SCS in cases of focal pain.3 Recently, our laboratory demonstrated that a single treatment with external low intensity focused ultrasound (liFUS) to the DRG produced significant improvements in mechanical, thermal, and noxious pain for 3–5 days in rodent models of chronic pain.4–7 Specifically, we have shown that liFUS treatment of the L5 DRG induces antinociceptive effects, in a dose-dependent manner, without causing histological damage.4,5,7,8 Repeated treatments showed no evidence of tachyphylaxis.8

While the therapeutic use of electrical stimulation is commonplace, thermal energy at lower doses has been used sparingly in the modulation of chronic pain.9–12 Radiofrequency technologies have been shown to provide short-term pain relief. However, the inability to conform the treatment zone to the diseased tissue, while limiting exposure of normal tissue, has restricted utility. Further, this treatment remains invasive.13,14 External ultrasound treatment has been effectively used in humans primarily in the context of physical therapy for acute pain relief, with the effects likely attributable to relaxation of the muscle and tendons.15,16 FUS is currently used clinically at doses that result in ablation (e.g., ablation of brain tissue to treat movement disorders); however, modulatory liFUS treatments remain in the research phase.17–22 One reason for this lack of translation into the clinic is the absence of devices capable of reaching deeper nervous tissue for precise modulation.23,24

liFUS can be delivered through an external handheld, water-coupled, volume-focused applicator that produces low-intensity waveforms capable of modulating nerves without causing damage. Our existing device was adequate for use in rodents but necessitated modification to target deeper structures.5,6 In this study, we employed our new liFUS array to reduce allodynia and pain behavior in a common peroneal nerve injury (CPNI) model in swine.

Methods

CPNI Swine Model

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, 24 hours after arrival, 7- to 8-week-old castrated male Yorkshire farm pigs (Parson’s) began a 1-week habituation process. Each day, animals were allowed out of their cages to adjust to their new surroundings; pigs could socialize and interact within a controlled environment. Researchers also spent 20 minutes sitting with animals daily, and personnel were kept constant throughout the course of the study. Sling training began 48 hours after arrival. Animals were lifted into a sling (Lomir Biomedical) twice a day to acclimate to the sling prior to behavioral testing. All animals were housed in pens (188 × 88 cm), and the lights remained on from 7 am to 7 pm. Feed was provided twice a day (total 3% body weight per day: Envigo Teklad miniswine diet) with water freely available. A plastic ball or pin was provided for enrichment.

For the CPNI surgery, a xylazine (2.2 mg/kg), ketamine (2.2 mg/kg), and telazol (4.4 mg/kg) mixture was administered subcutaneously (s.c.) in combination with 5% isoflurane to induce anesthesia. Animals were maintained with 1.6%–2% isoflurane during surgery. Carprofen (2.2 mg/kg) and cefazolin (4.4 mg/kg) were also administered (s.c.). Body temperature was maintained at 38.6°C ± 0.5°C25 throughout, and lactated Ringer’s solution was provided (7 ml/kg/hr intravenously; Baxter Healthcare Corporation). Animals were placed in the prone position, the left hind leg was shaved, and the area 2 cm posterior to the fibular head (2 cm above and 2 cm below) was marked as an external landmark for the incision. Bupivacaine was injected (up to 2 mg/kg s.c.) at the incision site. A sterile drape and Ioban (3M) were placed to create a sterile field. The incision was made, followed by muscle coagulation via electrocautery and blunt dissection to reveal the common peroneal nerve (CPN); two silk sutures were placed around the nerve, 1–2 cm apart. Muscle layers and subcutaneous tissue were reapproximated, and the Ford inter-locking suture method was used for skin closure. Animals were allowed 7 days to recover.

Sensory Threshold and Behavior Testing

The first 4 animals underwent behavioral testing for 1 week only. The follow-up period was extended to 4 weeks for the last 4 animals in the first group because improvements in motor responses were maintained after 1 week and warranted further exploration for duration of effects. This time period was truncated to 3 weeks in the second cohort as behavioral findings remained stable between weeks 3 and 4 and the increasing animal size due to rapid growth posed risks for the animal facility staff with continued lifting.

Prior to liFUS, baseline post-CPNI surgical responses were evaluated with both von Frey filaments (VFFs) and thermal testing while the pigs were in a Lomir Biomedical sling, as described previously.26 Weighted VFFs (ranging from 1 to 284 g) were used to determine mechanical sensitivity, both to confirm allodynia after the CPNI surgery and to assess any changes in mechanical thresholds caused by the liFUS treatment. Mechanical thresholds were determined using the Chaplan up-down method.27 VFFs were applied to the skin 3 times for 3–5 seconds just above the dorsal aspect of the hind hoof, and 50% mechanical thresholds were calculated based on a six-response test. Fibers were applied in ascending force order until a response was elicited. Allodynia was defined as a response to VFFs weighted at 4.0 g or less, and the CPNI surgery was considered to be successful if animals were allodynic 1 week after the CPNI. A response was defined as kicking, hoof guarding, or withdrawal. If the pig did not react, the VFF with the next highest weight was used. Or, if there was a response, the VFF with the next lowest weight was used. After liFUS, the test was repeated, and treatment success was defined as significant improvements from allodynic thresholds. If the animal did not respond to the highest-weight VFF (284 g), the test was terminated.

Thermal sensitivity was assessed (Medoc Pathway, CHEPS, Advanced Medical Systems). A heating probe was placed on the skin just above the dorsal aspect of the hind hoof, and the temperature was raised from 25°C to 50°C at 0.5°C per second. If the rising temperature elicited a response, the test was terminated and the temperature that the animal responded to was recorded. Thermal allodynia was defined as any response to the heating probe. After liFUS treatment, improvement was defined as a response to a higher temperature than in the allodynic state or no response to the highest temperature. A response was defined similarly to the VFF response, as kicking, hoof guarding, or withdrawal. All pigs received thermal testing, which necessitated 30–40 minutes in the sling at pre-liFUS and 24 hours and 1 week post-liFUS.

Social and motor behavior were determined by a method previously used in minipigs.28 During a 10-minute period, freely moving animals were assessed and scored for appearance (0–1), vocalization (0–2), and weight-bearing of the leg (0–1). After CPNI surgery, motor score impairment, specifically leg guarding, was another measure used to define allodynia. Improvement after liFUS was determined by lower motor scores. Social interactions were scored as agitation (0–2), aggression (0–2), isolation (0–1), and restlessness (0–2). For both tests, lower scores represent lower impairment.

liFUS Treatment

In the first cohort of pigs (group 1, age 7 weeks upon arrival, 13–14 kg; n = 8), liFUS treatment parameters were determined via a modified dose-response curve. The parameters ranged from 25 to 30 W for 3–4 minutes. The flow rate of circulating water around the probe varied from 20 to 26 ml/min and the temperature from 15°C to 25°C. For liFUS, animals were anesthetized with the same regimen as for CPNI surgery. The animal was placed in the prone position. The left L5–6 interface and the left L5 DRG were located by palpating the lumbar interspace at the level of the posterior iliac spine, a methodology we had verified with previous dissections. The liFUS application site was marked by measuring 9 cm laterally from this landmark (Fig. 1).

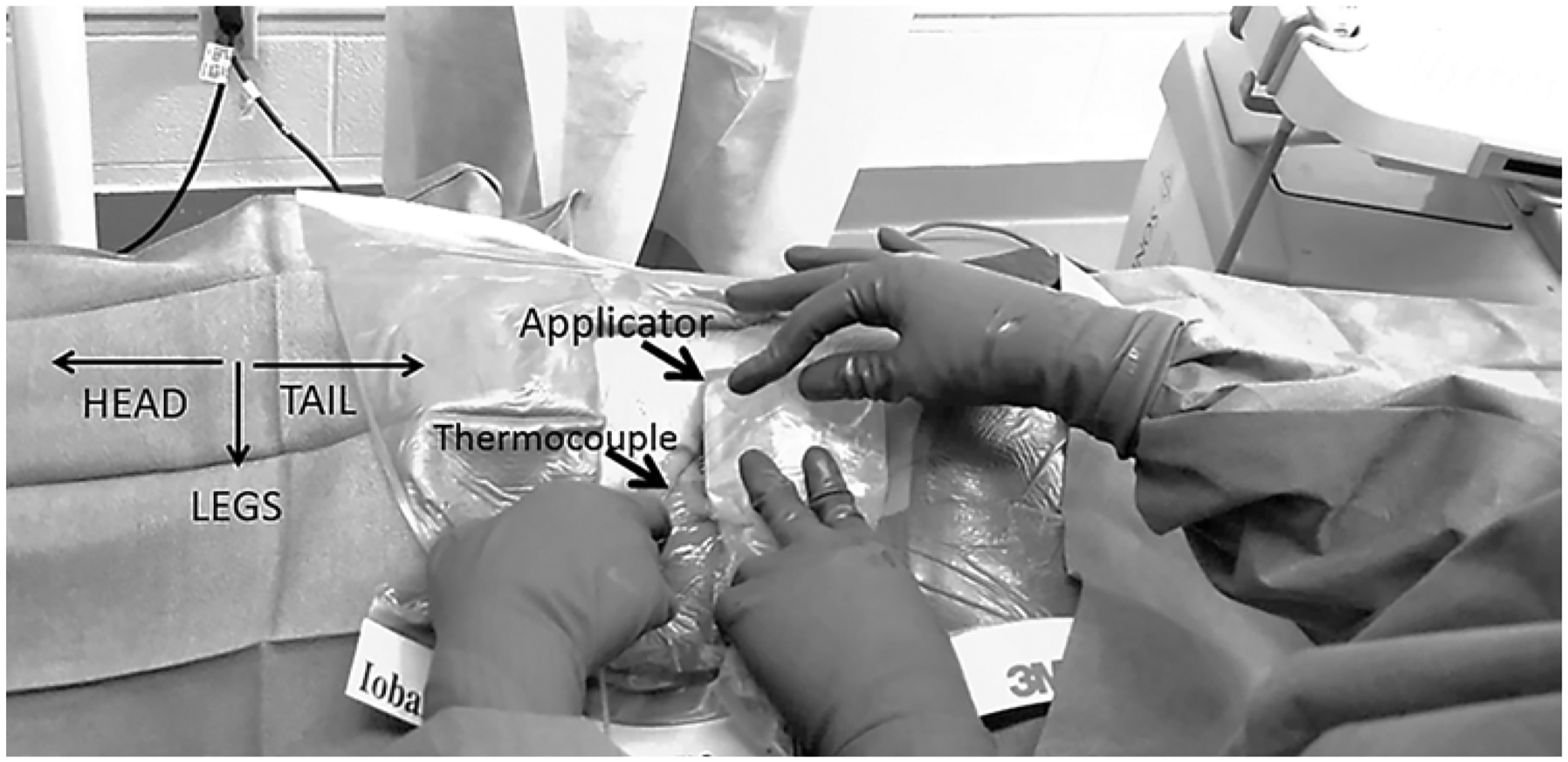

FIG. 1.

liFUS probe and thermocouple placement (SonixMDP, Ultrasonix). Relative placement of liFUS applicator probe and thermocouple probe during liFUS treatment.

The SonixMDP (Ultrasonix) ultrasound imaging system was used to visualize the L5 DRG, and a stab incision was made 1 cm above the probe to insert a thermocouple under direct ultrasound visualization. The thermocouple was placed extradurally, immediately adjacent to the DRG. Imaging and FUS probes were next placed in sterile pouches filled with Aquasonic 100 ultrasound gel (Southern Anesthesia Surgical). Gel was also applied to the outside of the plastic pouch covering each probe. The liFUS transducer array was focused to the DRG, and therapy was administered. The thermocouple remained in place after liFUS therapy and was removed when the tissue temperature returned to baseline levels. Maximum temperature increase and duration of temperature elevation during treatment were noted.

Concurrently, CPN nerve conduction velocities (NCVs) and amplitudes were monitored in all but the first 2 animals (Axoscope, Molecular Devices). The stimulating electrode delivered continuous alternating current for 30 seconds at 80 Hz, with a delay of 0.8 msec, duration of 14 msec, and voltage of 50 mV with gain of 5 mV for baseline recordings. Baseline measurements were recorded before liFUS treatment, after the animal underwent behavioral testing to confirm allodynia. After liFUS treatment, data were recorded for 30 seconds every 5 minutes.29 Data analysis focused on the change between baseline recordings and data recorded after liFUS to assess the impact of treatment of CPN NCVs. Sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) recordings were analyzed using Clampfit (Molecular Devices). This setup did not interfere with the liFUS recordings. In light of variability with our CPN amplitudes following liFUS, a Bair hugger heating blanket, set to 38°C (3M), was used to control animal temperature.30 The left hind leg temperature was also monitored using an infrared thermometer (Gaomu) before and during NCV and amplitude measurements.

Histological Analysis

After behavioral testing was complete, all animals were euthanized. Transcardiac perfusion was performed using heparinized saline (4 L), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (buffered, 5 L). The left L5 DRG, the left dorsal horn innervated by the DRG (DH; T15 to LI in swine), and the left CPN were removed. Samples were embedded in paraffin and then sliced at 5 μm. Fluoro-Jade (Sigma-Aldrich) and H&E staining were done using a modified protocol.31 Samples were imaged using a Zeiss AXIO Imager M2 microscope (×40) with a Hamamatsu Ocra-Flash 4.0 digital camera.

Results

Dose-Response Curve

The initial 8 pigs had a mean ± SEM weight of 13.88 ± 0.54 kg and received liFUS treatment 7 days after CPNI surgery. Treatment power, duration, and flow rate were varied to assess temperature changes at the DRG (Table 1). In 6 of 8 animals, temperature changes were maintained at low levels (1.12°C ± 0.31°C). Two treatment recordings were determined to be outside an acceptable range due to safety concerns with DRG temperatures of 9.2°C and 12.8°C. In the animal with the 12.8°C change, a first-degree skin burn also occurred. Another first-degree burn occurred in an animal with an appropriate DRG temperature change. In response to the second burn, we increased the coolant flow rate from 20 to 26 ml/min in future trials and changed the coolant temperature to 17°C.

TABLE 1.

liFUS treatment doses in smaller swine

| Swine ID | Weight Pre-liFUS (kg) | Treatment Power (W) | Treatment Time | Flow Rate (ml/min) | Adverse Events | Allodynia Improvement | Δ Temperature (°C) | Depth of DRG (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 181 | 13 | 25 | 3 mins 40 secs | 20 | None | Yes | 2.1 | 4 |

| 182 | 13.45 | 25 | 3 mins 40 secs | 20 | Burn | Yes | 1.6 | 4 |

| 183* | 13.36 | 25 | 3 mins | 27 | Activity-related hematoma | Yes | 1.5 | 3.5 |

| 184 | 11.79 | 30 | 3 mins 30 secs | 26 | Wound breakdown | Yes | 9.2 | 3.5 |

| 185* | 13.6 | 25 | 4 mins | 26 | Burn | Yes | 12.8 | 4 |

| 186 | 15 | 28 | 4 mins | 26 | Wound breakdown, burn | Yes | 1.3 | 3.5 |

| 187 | 17.32 | 28 | 3 mins 30 secs | 26 | None | Yes | 0.2 | 4 |

Animals received varied liFUS treatment doses with adjustments made to either the treatment power, time, or coolant water flow rate. Improvements in allodynia and adverse events were recorded in the 7 smaller animals for which liFUS treatment was successful.

Tissue collected for histological analysis.

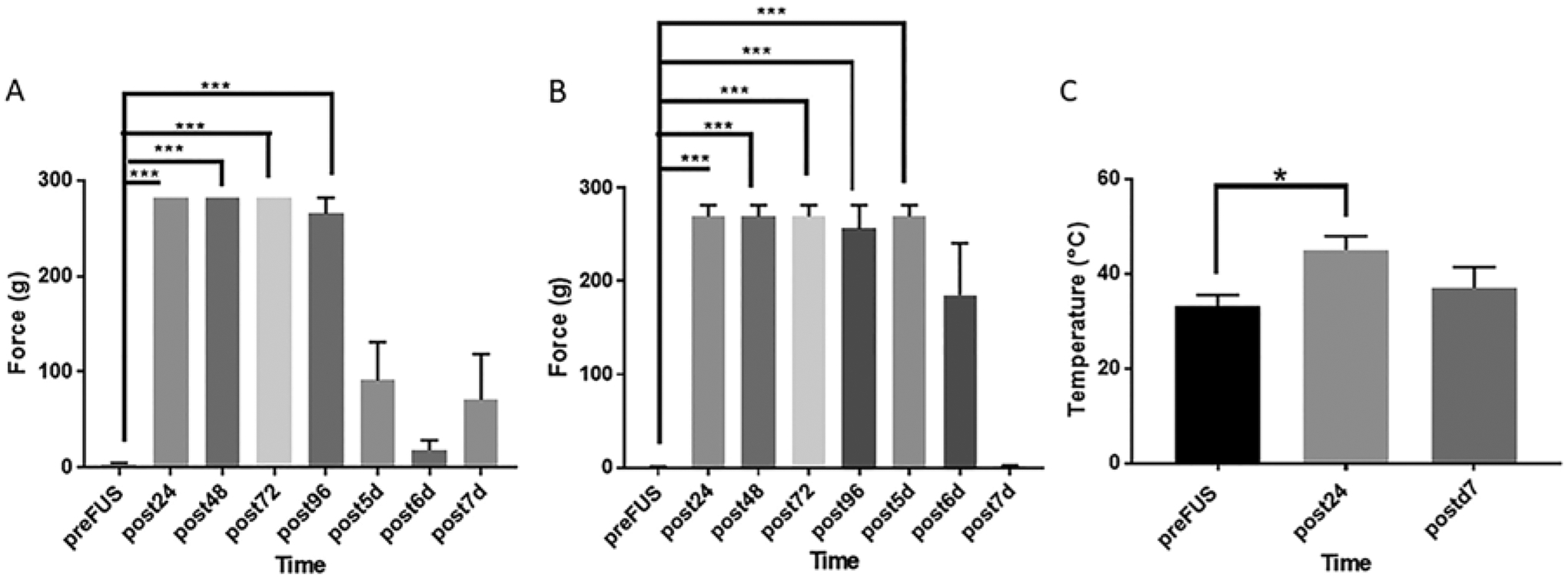

Following liFUS treatment, 7 of 8 animals showed significant reductions in nociceptive VFF responses and no longer displayed mechanical allodynia. Of note, we had to adapt our VFF assessments after the first 2 animals due to thickness of the ventral hind hoof. In the remaining 6 animals, the dorsal hind hooves were used. VFF scores significantly increased for 3 days following liFUS compared to the scores in the neuropathic state (3.93 ± 1.02 g; one-way repeated-measure ANOVA; main effect of liFUS, p < 0.001). Mechanical thresholds were still significantly improved at 96 hours (265.10 ± 16.79 g, p = 0.02) after treatment (Fig. 2A). Effects were not significant on days 5–7 (91.23 ± 39.78, 18.08 ± 10.54, and 70.75 ± 47.79 g, respectively).

FIG. 2.

Mechanical and thermal thresholds of the dorsal aspect of the left hind hoof. A: VFF (force in grams) pre- and post-liFUS treatment. One-way repeated-measure ANOVA revealed a main effect of liFUS treatment (p < 0.001; n = 6). Tukey post hoc comparison was used to determine the significance of individual time points. VFF scores significantly increased for 4 days following liFUS compared to the neuropathic state (3.93 ± 1.02 g, p < 0.001). Effects were no longer significant on days 5–7. B: One-way ANOVA of the effect of liFUS on VFF thresholds in larger animals (n = 4) revealed a similar significant main effect of liFUS (p < 0.001) when compared to post-CPNI baseline scores (0.99 ± 0.19 g) for up to 5 days after treatment. C: Thermal thresholds were found to significantly decrease following CPNI ligation surgery: 33.17°C ± 2.00°C (p = 0.03; n = 4) compared to baseline scores. Threshold scores increased (p = 0.02) 24 hours after liFUS treatment. Seven days post-liFUS treatment, thermal thresholds were no longer significantly different from baseline. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

CPN baseline SNAPs were recorded pre-liFUS and for 1 hour following liFUS. Four animals responded similarly, while 2 did not. For the 4 animals with similar baseline SNAP responses, significant increases in conduction velocity (one-way repeated-measure ANOVA; main effect of liFUS, p = 0.002) were revealed between the pre-liFUS and post-liFUS SNAPs (Table 2; Tukey post hoc test, p < 0.001). There were no significant changes in NCV after 30 minutes post-liFUS. There was also a significant decrease in SNAP amplitude following liFUS treatment (one-way repeated-measure ANOVA; main effect of liFUS, p < 0.001). This effect also lasted for 30 minutes after treatment (Table 2; Tukey post hoc test, p < 0.001). In the group with 2 animals, conduction velocity and amplitude were 10× higher at baseline and inconsistent with human nerve conduction study data in neuropathy.32 Due to the small number in this cohort, no statistical analysis was performed (pre-liFUS conduction velocity 7.18 ± 0.81 m/sec; amplitude 7.99 ± 0.06 mV). Neither measure displayed changes as a result of liFUS treatment (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Conduction velocity and amplitude in smaller swine

| Timepoint | Mean nerve conduction velocity (NCV, m/sec) ± SEM (n = 4) | p Value (NCV) | Amplitude (mV) ± SEM (n = 4) | p Value (amplitude) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-liFUS | 8.74 ± 0.54 | — | 1.68 ± 0.37 | — |

| Post-liFUS (mins) | ||||

| 5 | 10.85 ± 0.85 | 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.03 |

| 10 | 10.29 ± 0.75 | 0.004 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.03 |

| 15 | 10.49 ± 0.81 | 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.03 |

| 20 | 10.09 ± 0.67 | 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.04 |

| 25 | 10.29 ± 0.75 | 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.03 |

| 30 | 9.65 ± 0.63 | 0.001 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.03 |

| 35 | 8.47 ± 0.80 | 0.43 | 2.09 ± 2.08 | >0.99 |

| 40 | 8.31 ± 0.82 | 0.35 | 2.13 ± 2.11 | >0.99 |

| 45 | 8.30 ± 0.82 | 0.26 | 2.14 ± 2.12 | >0.99 |

| 50 | 8.42 ± 0.72 | 0.24 | 2.11 ± 2.10 | >0.99 |

| 55 | 8.24 ± 0.68 | 0.76 | 2.12 ± 2.11 | >0.99 |

| 60 | 7.92 ± 0.75 | 0.91 | 2.11 ± 2.10 | >0.99 |

NCV means ± SEMs with p values comparing pre-liFUS to post-liFUS treatment in smaller swine (n = 6).

After CPNI surgery, all 8 animals showed an increase in leg-guarding behavior (7 animals had a motor score of 1, and 1 animal had a motor score of 2). Social scores remained at baseline after CPNI. Twenty-four hours post-liFUS treatment, behavioral testing returned to a normal range in 7 of 8 animals, with motor scores returning to 0. One animal displayed abnormal social (score of 1 for displayed agitation) and motor (score of 1 for vocalization) responses. Return to baseline motor scores lasted up to 4 weeks post-liFUS after a single treatment.

Verification of Behavioral Response at Optimal Dose

We intentionally used a second group of larger animals (19.85 ± 0.63 kg; n = 4) to demonstrate the feasibility of our dosing paradigm developed in the first group of animals to modulate allodynic response. Specifically, to accommodate the depth of DRG (4.5–4.75 cm) in these larger animals, treatment power was increased to 28 W, time was varied from 3.5 to 4 minutes, and the probe water flow rate was maintained at 26 ml/min with water at 17°C–18°C (Table 3). The mean change in DRG temperature measured during liFUS treatment was 0.80°C ± 0.41°C in all 4 animals.

TABLE 3.

liFUS treatment doses in larger swine

| Swine ID | Weight Pre-liFUS (kg) | Treatment Power (W) | Treatment Time | Flow Rate (ml/min) | Adverse Events | Allodynia Improvement | Δ Temperature (°C) | Depth of DRG (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 188 | 17.9 | 28 | 3 mins 30 secs | 26 | None | Yes | 2.2 | 4.5 |

| 189* | 21.1 | 28 | 4 mins | 26 | None | Yes | 0.3 | 4.5 |

| 190* | 20.8 | 28 | 3 mins 30 secs | 26 | None | Yes | 0.3 | 4.75 |

| 191 | 19.6 | 28 | 4 mins | 26 | None | Yes | 0.4 | 4.5 |

Animals received varied liFUS treatment doses with adjustments made to either the treatment power, time, or flow rate. Improvements to allodynia and adverse events were recorded in the 4 larger animals in which the treatment algorithm was tested.

Tissue collected for histological analysis.

CNPI mechanical nociceptive thresholds significantly improved as a result of liFUS (one-way ANOVA with repeated measures; main effect of liFUS, p < 0.001). Post-CPNI baseline VFF scores were 0.99 ± 0.19 g. After liFUS treatment, mechanical allodynia reversed and was significantly improved (Fig. 2B; Tukey post hoc comparison) at 24 hours (269.6 ± 12.25 g, p < 0.001), 48 hours (269.6 ± 12.25 g, p < 0.001), 72 hours (269.6 ± 12.25 g, p < 0.01), and 96 hours (269.6 ± 12.25 g, p < 0.001) post-liFUS. Notably, at 5 days post-liFUS, animals still showed significant improvements (269.6 ± 12.25 g, p < 0.001). The effect of a single liFUS treatment was no longer significant at the later time points tested.

Increases in baseline thermal sensitivity were observed post-CPNI (33.17°C ± 2.00°C). Twenty-four hours after liFUS treatment, thermal sensitivity was significantly reduced and a response threshold of 45.00°C ± 2.50°C was measured (Fig. 2C; one-way repeated-measure ANOVA; main effect of liFUS, p = 0.02). This improvement was significant for 24 hours posttreatment (Tukey post hoc test, p = 0.03). At 7 days post-liFUS, thermal thresholds (37.04°C ± 3.74°C, p = 0.50) were similar to post-CPNI baselines (Fig. 2C). Motor scores improved from 1 at baseline to 0 after liFUS treatment, and this improvement persisted in all animals from 24 hours to 3 weeks post-liFUS.

A one-way repeated-measure ANOVA between pre-liFUS and post-liFUS SNAPs revealed significant increases in conduction velocity (p = 0.01) and decreases in amplitude (p < 0.001) following liFUS for 30 minutes post-liFUS (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Conduction velocity and amplitude in larger swine

| Timepoint | NCV (m/sec; n = 4) | p Value (NCV) | Amplitude (mV; n = 4) | p Value (amplitude) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-liFUS | 8.98 ± 0.38 | — | 2.52 ± 0.16 | — |

| Post-liFUS (mins) | ||||

| 5 | 12.06 ± 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.003 |

| 10 | 10.71 ± 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.003 |

| 15 | 11.34 ± 0.40 | 0.003 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.002 |

| 20 | 11.37 ± 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.13 ± 0.08 | 0.002 |

| 25 | 11.27 ± 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.002 |

| 30 | 10.21 ± 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.003 |

NCV mean values ± SEMs with p values comparing pre-liFUS to timepoints after liFUS treatment in larger swine (n = 4).

Histological Analysis

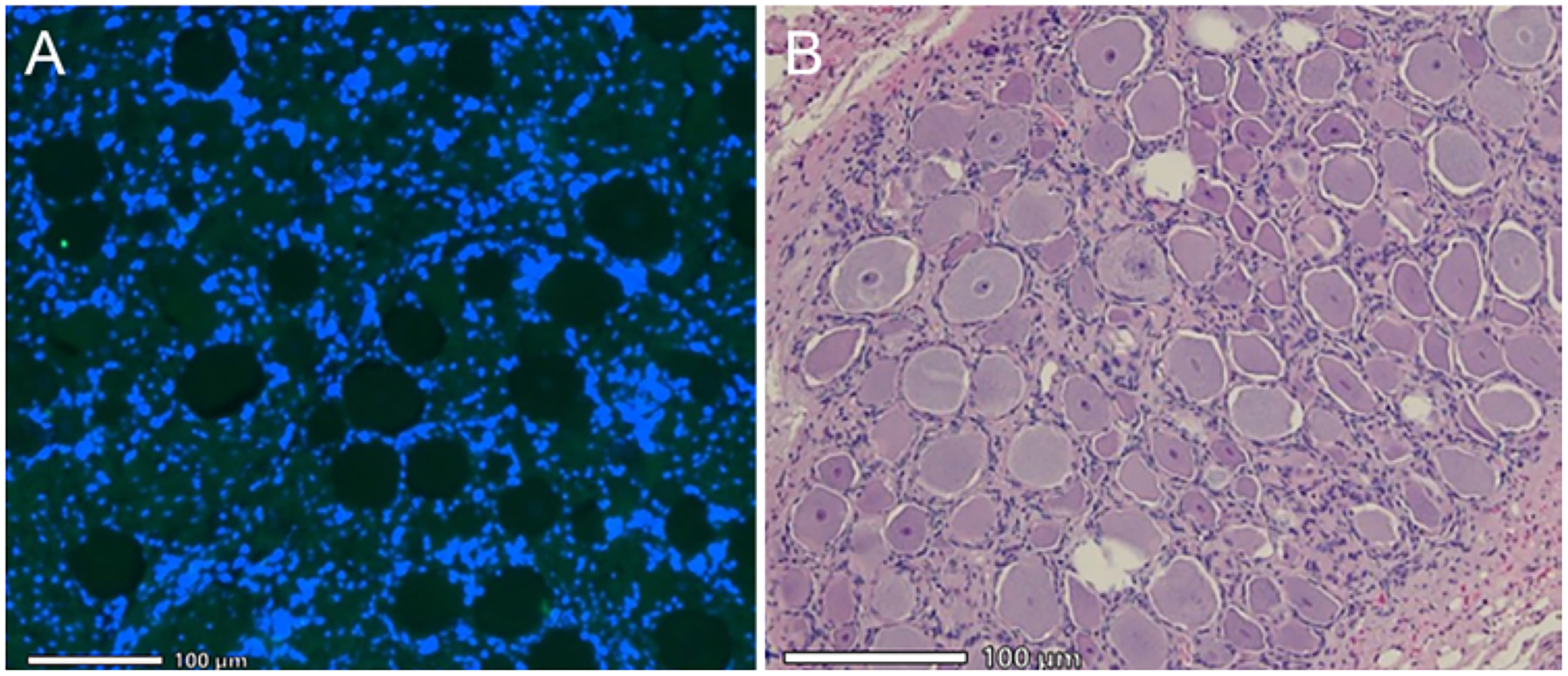

A subset of DRG and DH (n = 4) samples from liFUS-treated animals were stained using Fluoro-Jade and H&E and then evaluated for histological damage (see Tables 1 and 3). Specifically, we examined tissues from liFUS-treated animals with normal and high-temperature changes at the DRG (see Tables 1 and 2). Samples were taken 1 week after liFUS in animals with a normal temperature change and 4 weeks after liFUS for the high-temperature animals. No indications of pyknosis or cellular edema were observed in either group after H&E staining of the L5 DRG post-liFUS. DH samples revealed DH and dorsal entry zone neurons that were within healthy limits. Additionally, our Fluoro-Jade staining revealed no signs of cellular death in the DRG (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

L5 DRG histology. A: Fluoro-Jade staining of left DRG 7 days post-liFUS at ×20 with DAPI counterstain showing no signs of neurodegeneration. B: H&E stain of left DRG at ×20 shows morphologically normal DRG cells, with intact Nissl substance without signs of pyknosis or edema.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of external liFUS in modulating the DRG in neuropathic swine. Preliminary experiments with 8 swine established the working parameters needed for treatment. Optimal device results were confirmed in a second group of larger animals. In both groups, there was a significant improvement in mechanical and thermal thresholds in a large-animal CPNI model. Further, liFUS-treated animals had improved motor scores, which returned to baseline levels for the remainder of the follow-up period. No evidence of neuronal degeneration was seen using Fluoro-Jade staining, and no signs of cell damage were displayed with H&E staining, even in cases where temperature changes exceeded 9°C at the DRG. We began mechanistic studies by demonstrating that liFUS-treated animals showed increased CPN NCV and reduced amplitude for 30 minutes post-liFUS.

Administration of liFUS significantly improved thermal and mechanical allodynia in the in vivo swine model and effectively reached DRG targets up to 4.75 cm below the skin surface. The reversal of mechanical allodynia lasted for 5 days; a similar reversal of thermal allodynia lasted for 24 hours. No histological damage occurred following treatment, and mean ± SEM temperature changes were 0.80°C ± 0.41°C. After liFUS treatment, motor scores were improved and remained improved for the duration of follow-up. Improvement in leg-guarding behavior might have occurred over time, regardless of liFUS treatment. However, the fact that it was present in all animals on day 6 post-CPNI and resolved 24 hours after liFUS treatment (day 7 post-CPNI) strongly argues that this change was the direct result of liFUS.

To verify that the liFUS was reaching the DRG, we monitored conduction velocity. As anticipated, after CPNI surgery, swine CPNs displayed slower conduction velocities, similarly to CPNs in humans with neuropathic pain.33,34 Immediately after liFUS treatment, NCVs returned to what is clinically considered to be a healthy range for the porcine CPN.35 NCV and amplitude can be utilized as noninvasive measures of successful liFUS delivery and may be useful in future clinical trials to assess accuracy of liFUS targeting at the DRG.

Early in the study, our values for NCVs and amplitudes were less reliable and inconsistent with the literature.32 The addition of a heating blanket resolved the issue. DRG histopathology was consistent among all samples stained with H&E and Fluoro-Jade, even in cases where the tissue temperatures exceeded the recommended > 2°C change at the treatment site. Regardless of the time at which tissue was collected after liFUS treatment (1, 3, or 4 weeks), there were no histological changes as a result of liFUS.

During our “dose-response” first cohort, superficial skin burns were seen in 2 animals directly below the liFUS application site. In order to rectify this initial problem, we lowered the power and time of treatment, while increasing coolant flow and reducing the temperature of coolant. The coolant provides coupling between the transducer membrane interface and the skin, and prevents heat buildup at the application site. Ultimately, we determined the optimal dose to be 25 W, with a frequency of 2.475 MHz and a pulse of 38 Hz at a 50% duty cycle for 3.5 minutes and a coolant rate of 26 ml/min at 17°C. We increased the amplitude to 28 W to account for greater depth in the second group of animals.

Though these data are not supported by a control group due to logistics and expenses of large-animal models, our previous rodent work demonstrated that the thermocouple did not affect results. Specifically, introduction of the extradural thermocouple did not alter mechanical thresholds or histology.4 Further, work with CPNI and sciatic nerve injury by our group and others demonstrates that the natural history of nerve injury results in at least 4 weeks of allodynia36–39 (also A. Liss et al., unpublished data, 2020).

We acknowledge that there are limitations to this work. The iterative nature of this work limited sample size. However, we were able to show proof of principle and use an algorithm to determine appropriate adjustments in power to effectively deliver liFUS treatment to tissue targets at depths of up to 6 cm. Further design modifications will be required prior to moving to human studies. Specifically, greater depth is needed and a noninvasive means of thermal monitoring is necessary. We aim to make this liFUS a completely noninvasive treatment during clinical use. We are currently exploring ultrasound technology, which enables us to noninvasively monitor temperature while offering treatment. Additionally, our current study only used castrated male swine. In the future, female swine should be incorporated as there is evidence that females and males respond differently to pain and treatment.40,41

Conclusions

Taken together, we have demonstrated that external liFUS of the DRG in a large-animal model of chronic neuropathic pain results in significant changes in mechanical and thermal pain behaviors and long-lasting changes in motor behavior. In addition, thermal tissue monitoring and NCVs demonstrated that liFUS reached the DRG target. These measures can be used to monitor liFUS therapy acutely.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant SBIR 1 R43 NS107076-01A1 (Soft-Focused HIFU [High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound] Treatment of Common Peroneal Nerve Injury). Dr. Pilitsis receives non–study-related grant support from NIH (grants 2R01CA166379-06 and U44NS115111).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CPN

common peroneal nerve

- CPNI

CPN injury

- DH

left dorsal horn innervated by the DRG

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- liFUS

low intensity focused ultrasound

- NCV

nerve conduction velocity

- s.c.

subcutaneously

- SNAP

sensory nerve action potential

- VFF

von Frey filament

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Pilitsis is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Nevro, TerSera, Medtronic, Saluda, and Abbott and receives grant support from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott, Nevro, and TerSera. She is a medical advisor for Aim Medical Robotics and Karuna and has stock equity. Clif Burdette, Paul Neubauer, Emery Williams, and Goutam Ghoshal are employees of Acoustic MedSystems, Inc.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Pilitsis, Hellman, Burdette. Acquisition of data: Pilitsis, Hellman, Maietta, Clum, Byraju, Raviv, Staudt, Shin, Nalwalk. Analysis and interpretation of data: Hellman, Byraju, Qian, Pilitsis. Drafting the article: Hellman. Critically revising the article: Pilitsis, Nalwalk. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: Pilitsis. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Pilitsis. Statistical analysis: Hellman. Administrative/technical/material support: Jeannotte, Ghoshal, Neubauer. Study supervision: Pilitsis. Device development: Ghoshal, Neubauer, Williams, Heffter, Burdette.

References

- 1.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(36):1001–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar K, Taylor RS, Jacques L, et al. The effects of spinal cord stimulation in neuropathic pain are sustained: a 24-month follow-up of the prospective randomized controlled multicenter trial of the effectiveness of spinal cord stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(4):762–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deer TR, Levy RM, Kramer J, et al. Dorsal root ganglion stimulation yielded higher treatment success rate for complex regional pain syndrome and causalgia at 3 and 12 months: a randomized comparative trial. Pain. 2017;158(4):669–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hellman A, Maietta T, Byraju K, et al. Low intensity focused ultrasound modulation of vincristine induced neuropathy. Neuroscience. 2020;430:82–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellman A, Maietta T, Byraju K, et al. Effects of external low intensity focused ultrasound on electrophysiological changes in vivo in a rodent model of common peroneal nerve injury. Neuroscience. 2020;429:264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prabhala T, Hellman A, Walling I, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for neuropathic pain induced by common peroneal nerve injury. Paper presented at: 86th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons; April 28–May 2,2018; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youn Y, Hellman A, Walling I, et al. High-intensity ultrasound treatment for vincristine-induced neuropathic pain. Neurosurgery. 2018;83(5):1068–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prabhala T, Hellman A, Walling I, et al. External focused ultrasound treatment for neuropathic pain induced by common peroneal nerve injury. Neurosci Lett. 2018;684:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moretti B, Garofalo R, Genco S, et al. Medium-energy shock wave therapy in the treatment of rotator cuff calcifying tendinitis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13(5):405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juch JNS, Maas ET, Ostelo RWJG, et al. Effect of radiofrequency denervation on pain intensity among patients with chronic low back pain: the Mint randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2017;318(1):68–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keskin C, Özdemir Ö, Uzun İ, Güler B. Effect of intracanal cryotherapy on pain after single-visit root canal treatment. Aust Endod J. 2017;43(2):83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajfur J, Pasternok M, Rajfur K, et al. Efficacy of selected electrical therapies on chronic low back pain: a comparative clinical pilot study. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:85–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanderhoek MD, Hoang HT, Goff B. Ultrasound-guided greater occipital nerve blocks and pulsed radiofrequency ablation for diagnosis and treatment of occipital neuralgia. Anesth Pain Med. 2013;3(2):256–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanelderen P, Rouwette T, De Vooght P, et al. Pulsed radiofrequency for the treatment of occipital neuralgia: a prospective study with 6 months of follow-up. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(2):148–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yildirim MA, Öneş K, Gökşenoğlu G. Effectiveness of ultrasound therapy on myofascial pain syndrome of the upper trapezius: randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Rheumatol. 2018;33(4):418–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nayak R, Banik RK. Current innovations in peripheral nerve stimulation. Pain Res Treat. 2018;2018:9091216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi GS, Kwak SG, Lee HD, Chang MC. Effect of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on chronic central pain after mild traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(3):246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu T, Zhang N, Wang Z, et al. Endogenous catalytic generation of O2 bubbles for in situ ultrasound-guided high intensity focused ultrasound ablation. ACS Nano. 2017;11(9):9093–9102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yildirim A, Chattaraj R, Blum NT, et al. Phospholipid capped mesoporous nanoparticles for targeted high intensity focused ultrasound ablation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6(18):1700514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi Y, Ying X, Hu X, Shen H. Pain management of pancreatic cancer patients with high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2017;30(1)(suppl):303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao J, Zhao F, Shi Y, et al. The efficacy of a new high intensity focused ultrasound therapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(10):2105–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao J, Shi Z, Zhou J, et al. Cesarean scar pregnancy: comparing the efficacy and tolerability of treatment with high-intensity focused ultrasound and uterine artery embolization. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43(3):640–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park J, Lee YJ, Kim ED. Clinical effects of pulsed radiofrequency to the thoracic sympathetic ganglion versus the cervical sympathetic chain in patients with upper-extremity complex regional pain syndrome: a retrospective analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(5):e14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esparza-Miñana JM, Mazzinari G. Adaptation of an ultrasound-guided technique for pulsed radiofrequency on axillary and suprascapular nerves in the treatment of shoulder pain. Pain Med. 2019;20(8):1547–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Pork Board. Swine Health Recommendations: Exhibitors of All Pigs Going to Exhibits or Sales. Published 2013. Accessed November 18,2020. https://datcp.wi.gov/Documents/SwineExhibitsSales.pdf

- 26.Hellman A, Maietta T, Clum A, et al. Development of a common peroneal nerve injury model in domestic swine for the study of translational neuropathic pain treatments. J Neurosurg. Published online April 16, 2021. doi: 10.3171/2020.9.JNS202961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, et al. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53(1):55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castel D, Willentz E, Doron O, et al. Characterization of a porcine model of post-operative pain. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(4):496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korte N, Schenk HC, Grothe C, et al. Evaluation of periodic electrodiagnostic measurements to monitor motor recovery after different peripheral nerve lesions in the rat. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(1):63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrera E, Sandoval MC, Camargo DM, Salvini TF. Motor and sensory nerve conduction are affected differently by ice pack, ice massage, and cold water immersion. Phys Ther. 2010;90(4):581–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmued LC, Albertson C, Slikker W Jr. Fluoro-Jade: a novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 1997;751(1):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim KH, Park BK, Kim DH, Kim Y. Sonography-guided recording for superficial peroneal sensory nerve conduction study. Muscle Nerve. 2018;57(4):628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SM, Chun KW, Chang HJ, et al. Reducing neck incision length during thyroid surgery does not improve satisfaction in patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(9):2433–2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedowitz RA, Garfin SR, Massie JB, et al. Effects of magnitude and duration of compression on spinal nerve root conduction. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17(2):194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jezernik S, Wen JG, Rijkhoff NJ, et al. Analysis of bladder related nerve cuff electrode recordings from preganglionic pelvic nerve and sacral roots in pigs. J Urol. 2000;163(4):1309–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitsuzawa S, Ikeguchi R, Aoyama T, et al. The efficacy of a scaffold-free Bio 3D conduit developed from autologous dermal fibroblasts on peripheral nerve regeneration in a canine ulnar nerve injury model: a preclinical proof-of-concept study. Cell Transplant. 2019;28(9–10):1231–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bundgaard L, Sørensen MA, Nilsson T, et al. Evaluation of systemic and local inflammatory parameters and manifestations of pain in an equine experimental wound model. J Equine Vet Sci. 2018;68:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reddy CG, Miller JW, Abode-Iyamah KO, et al. Ovine model of neuropathic pain for assessing mechanisms of spinal cord stimulation therapy via dorsal horn recordings, von Frey filaments, and gait analysis. J Pain Res. 2018;11:1147–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reddy RC, Chen GH, Newstead MW, et al. Alveolar macrophage deactivation in murine septic peritonitis: role of inter-leukin 10. Infect Immun. 2001;69(3):1394–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plesh O, Adams SH, Gansky SA. Racial/ethnic and gender prevalences in reported common pains in a national sample. J Orofac Pain. 2011;25(1):25–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pieh C, Altmeppen J, Neumeier S, et al. Gender differences in outcomes of a multimodal pain management program. Pain. 2012;153(1):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]