Abstract

Female mice bearing targeted mutations in the interleukin-6 or inducible nitric oxide synthase locus mounted effective immune responses following vaginal infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Chlamydial clearance rates, local Th1 cytokine production, and host antibody responses were similar to those of immunocompetent control mice. Therefore, neither gene product appears to be critical for the resolution of chlamydial infections of the urogenital epithelium.

Infection of the murine female genital tract with the sexually transmitted intracellular bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis stimulates an acute influx of neutrophils and the subsequent accumulation of mononuclear leukocytes in the cervicovaginal and endometrial mucosa. Enhanced synthesis of several cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), as well as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS or NOS-2), can be detected both locally and systemically (35), consistent with a predominant role for type 1 CD4+ T cells in host resistance to this pathogen (8, 41). This hypothesis is supported by the capacity of anti-IL-12 but not anti-IL-4 monoclonal antibody treatment to interfere with immune clearance of genital infections (35). IFN-γ, which is the dominant cytokine produced during murine chlamydial infections, is required to prevent systemic dissemination of bacteria but not to eliminate the majority of Chlamydia organisms from genital tract epithelium (13, 35). The extent to which the other cytokines detected in this mouse model contribute to local chlamydial clearance remains to be determined.

IL-6 is a small pleiotropic protein identified originally for its role in promoting the terminal differentiation of B lymphocytes. Produced by a variety of cell types (31), IL-6 also acts as an endogenous pyrogen (9), signals the production of acute-phase reactants (19), and promotes the survival of hematopoietic stem cells (5), hepatocytes (14), neurons (28), and T cells (31). The potential contribution of IL-6 to mucosal immunity has focused on its capacity to enhance immunoglobulin A (IgA) production by isotype-committed B cells. Ramsay et al. (36) reported that IL-6 knockout (KO) mice possessed fewer IgA-specific plasma cells in mucosal tissues than their genetically intact counterparts, a relative deficiency that persisted after mucosal immunization with soluble or virus-associated proteins. This observation was not supported by the experiments of Bromander et al. (7), who detected comparable numbers of IgA-secreting cells and titers of IgA antibodies in IL-6-deficient and wild-type mice, either before or after infection with Helicobacter felis. While the basis for these differences is unclear, it can be inferred that IL-6 is not required for the efficient production of secretory IgA to all mucosal antigens.

Nitric oxide (NO−), a simple but relatively unstable radical synthesized from l-arginine by iNOS, is a potent mediator active in neurotransmission, platelet aggregation, vascular smooth muscle relaxation, septic shock, and immunity to certain intracellular pathogens (12, 27). Macrophage synthesis of NO− is regulated primarily by IFN-γ-mediated induction of transcriptional activating factors for the iNOS promoter (37) and is enhanced by costimulation with TNF-α or TNF-β (16). NO− has been implicated in in vitro or in vivo models of host resistance to Leishmania major (30, 43) Plasmodium spp. (25, 40), Schistosoma mansoni (26), Francisella tularensis (2), Toxoplasma gondii (1), Listeria monocytogenes (4, 6), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (10), with monoclonal antibodies against NO−-inducing cytokines or specific iNOS inhibitors. However, mice genetically deficient in iNOS or in the IFN-γ regulatory factor required for NO− induction retained their in vivo resistance to Listeria (18), Mycobacterium avium (17), and the acute stage of T. gondii infection (39). iNOS activity has also been implicated in host immunity to Chlamydia, based on the induction of nitric oxide in infected epithelial cells cocultured with Chlamydia-specific T-cell clones (24) and on the inhibition of clearance by exposure to iNOS inhibitors in vivo or in vitro (22, 23). In the present study, mice carrying induced mutations in the gene encoding either iNOS or IL-6 were used in order to obtain direct, definitive data on the role of these gene products in chlamydial immunity. Our findings show that neither iNOS nor IL-6 is critical to chlamydial clearance in vivo.

Female IL-6 KO mice on a 129/J × C57BL/6 intercross background (STOCK Il6tml), parental C57BL/6, parental 129/J, and (129/J × C57BL/6)F2 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) at 6 to 8 weeks of age. Breeding pairs of iNOS KO mice on a 129/J × C57BL/6J background were obtained through the generosity of Carl Nathan, Cornell University Medical College, and bred in a specific-pathogen-free, American Association for Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facility at Rocky Mountain Laboratories. Inheritance of the iNOS mutation was confirmed by PCR analysis of tail DNA, using primers provided by C. Nathan that detect the mutant or wild-type allele. Animals were injected subcutaneously with 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera; Upjohn, Kalamazoo, Mich.) to synchronize estrus 5 days prior to infection with the mouse pneumonitis (MoPn) strain of C. trachomatis, which was grown in HeLa 229 cells and purified by discontinuous density centrifugation as previously described (34). A total of 1,500 inclusion-forming units (IFU) of MoPn was deposited into the vaginal vault in 5 μl of 150 mM sucrose–10 mM sodium phosphate–5 mM l-glutamic acid (pH 7.2), equivalent to 100 50% infective doses. The course of infection was monitored by swabbing the vaginal vault with Calgiswabs (Spectrum Medical Industries, Los Angeles, Calif.) at intervals after infection followed by enumeration of recovered IFU on HeLa cell monolayers by indirect immunofluorescence (34).

Humoral and cellular assays of immunity.

Serum and secretory (vaginal wash) antibodies reactive with C. trachomatis MoPn were isotyped by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse Ig sera (class and subclass specific; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) as previously described (34). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay titer is defined as the highest serum dilution giving an absorbance (A405) that was at least threefold over that obtained with nonimmune sera. Cytokine production within the genital tract was assessed by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, using Trizol-extracted RNA (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA was reverse transcribed by using a GeneAmp RNA PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) and amplified as previously described (35). Primers used for amplification of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT), IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, the p40 subunit of IL-12 (IL-12p40), IFN-γ, iNOS, and TNF-α were published previously (35), and primer pairs for amplification of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) were purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, Calif.). Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed by using the same primers and protocol, with the addition of 0.025 μM [32P]dCTP (400 Ci/mmol; Amersham Life Science Inc., Arlington Heights, Ill.) to PCR mixtures. HPRT PCR was run for 26 cycles of amplification and IL-12p40 PCR for 30 cycles, which falls within the linear range of each amplification curve as determined in preliminary experiments. PCR products were quantitated by using a PhosphorImager 445 SI detection system (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.) and standardized to the level of HPRT product in each RNA sample. IL-12p40 expression in standardized samples is expressed in arbitrary units based on pixel density of autoradiographs. Cytokine production from spleen cells was measured after 3 days in culture as described previously (35). Histopathology was performed by Histopath of America (Clinton, Md.).

Chlamydial clearance in mutant and normal mice.

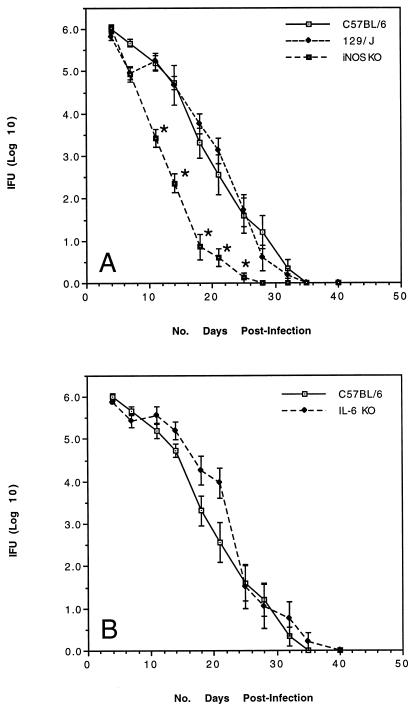

The influence of IL-6 and the iNOS-driven effector pathway on elimination of C. trachomatis from the female genital tract was assessed in mice carrying targeted mutations in the respective genes. Mutant and control mice were infected vaginally with C. trachomatis and cervicovaginal shedding was measured twice weekly until organisms were no longer detected. In two separate experiments, the kinetics of chlamydial shedding and the time required for complete clearance of infections were similar in IL-6 KO, iNOS KO, and genetically matched, immunologically competent control mice (Fig. 1). In fact, mice deficient in iNOS consistently resolved infections at a slightly more rapid rate than their normal counterparts. Expression of adaptive immunity to Chlamydia was also similar in mutant and normal mice in that the recovery of infectious organisms following secondary infection was minimal (<200 IFU at 4 days postinfection in all animals) and transient, with complete clearance by 10 days postinfection (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Clearance of C. trachomatis MoPn from the genital tracts of iNOS KO mice (A) or IL-6 KO mice (B) compared to control mice on the same genetic background (n = 10 mice/group). Asterisks indicate significant differences in the recovery of bacteria compared to control animals, as determined by Student’s t-test analysis of log-transformed data (P < 0.05).

Immune responsiveness of mutant and normal mice.

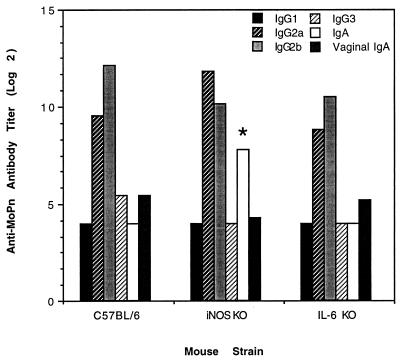

The ability of iNOS or IL-6 KO mice to resolve Chlamydia infections at the same rate as genetically intact control animals implied that the missing gene products were not required for an effective response to this epithelial pathogen. However, the extent to which these deletions may have altered other aspects of the host immune response such as the production of anti-Chlamydia antibodies or mononuclear cell-derived cytokines remained to be determined. Analysis of serum and vaginal wash antibody responses at 18 days postinfection revealed few differences between groups. Antibody titers in animals lacking IL-6 were nearly identical to those of genetically intact control mice (Fig. 2), with antibodies of the IgG2 subclass predominating all responses. The magnitude and isotype distribution of anti-Chlamydia antibodies in iNOS KO mice was also similar to that of control animals with the exception of significantly higher serum IgA titers in mutant mice (Fig. 2). However, the biologic impact of this increase is probably negligible since vaginal wash IgA titers in iNOS KO mice were similar to those of control animals.

FIG. 2.

Isotype distribution of serum and mucosal (vaginal wash) Chlamydia-specific antibodies in IL-6 KO, iNOS KO, and control mice assayed 18 days postinfection (n = 10 mice/group). iNOS KO mice produced significantly more serum IgA than control mice, as determined by the Mann-Whitney test (P < 0.05).

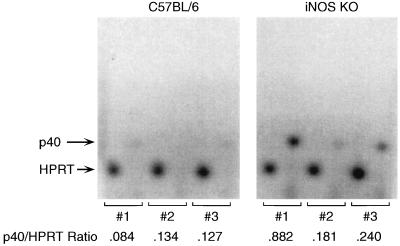

Cytokine production within Chlamydia-infected genital tracts was assessed by RT-PCR using primers specific for murine IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 p40, IFN-γ, TNF-α, TGF-β, and iNOS. As expected, IL-6 KO mice failed to generate an IL-6 PCR product and iNOS KO mice did not produce a detectable iNOS product (data not shown). Production of the other cytokines at 18 days postinfection was fairly comparable among mice from all groups with the exception of IL-12 p40, which appeared to be produced at higher levels in genital tissue from iNOS KO mice than from control mice, as determined by band intensity on agarose gels. This result was confirmed by using semiquantitative RT-PCR where the ratio of IL-12p40 to HPRT produced at 18 days postinfection ranged from 0.181 to 0.882 in three iNOS mice and from 0.084 to 0.134 in three C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 3). Variable enhancement of IL-12p40 synthesis in iNOS KO mice is consistent with the demonstration of accelerated bacterial clearance in these animals.

FIG. 3.

Relative production of IL-12p40 in the genital tracts of Chlamydia-infected C57BL/6 and iNOS KO mice. RNA extracted from infected genital tissues was reverse transcribed, and incorporation of [32P]dCTP into HPRT and IL-12p40 PCR products was quantitated as described in the text. Numbers represent the relative amount of IL-12p40 produced at 18 days postinfection as a proportion of the HPRT gene product produced in the same samples.

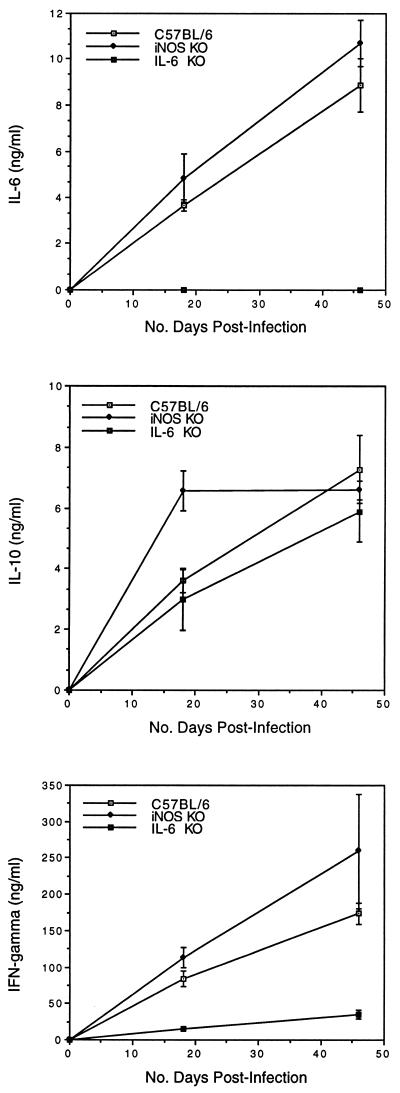

Spleen cells from Chlamydia-infected mice also produce high levels of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10, and IFN-γ (35). Splenocytes from mice deficient in iNOS produced significantly more IL-10 at 18 days postinfection compared to the response of control animals (Fig. 4). Enhanced production of IL-10 may reflect increased production of IL-12 since IL-10 is a regulatory cytokine produced in response to macrophage-derived IL-12 (33). However, attempts to measure IL-12 production by spleen cells were unsuccessful due to the paucity of macrophages in these cultures. Production of IL-6 and IFN-γ was not affected by the iNOS deletion as levels of these cytokines were comparable to those of control mice both during and following resolution of infection (Fig. 4). In contrast, splenocytes from IL-6 KO mice generated normal levels of IL-10 but significantly reduced levels of IFN-γ (Fig. 4). This deficit was not apparent at the site of infection since reverse transcription of genital tract IFN-γ RNA yielded similar levels of PCR product in normal and IL-6 KO mice (data not shown). Instead it appeared to be related to cellular deficits in the spleen in that spleens from IL-6-deficient animals were unusually small, approximately one-fifth the size of a normal C57BL/6 spleen. Defective erythropoiesis was considered to be the primary cause of microsplenia initially since the recovery of mononuclear cells was within normal limits. However, flow cytometric analysis revealed deficits in the T-cell compartment as well in that IL-6 KO mice had 35% fewer CD4+ cells and 48% fewer CD8+ T cells than normal animals (data not shown). This reduction was assumed to reflect the loss of IL-6 as a transcriptional activator (21) and T-cell growth factor (31).

FIG. 4.

Production of IL-6, IL-10, and IFN-γ by spleen cells from iNOS KO, IL-6 KO, or control mice. Spleens were harvested from 3 mice/group 18 days after infection with C. trachomatis MoPn, and mononuclear cells were restimulated in vitro with heat-killed MoPn. Values represent the concentration (mean ± standard error) of each cytokine present in supernatants after 72 h of culture. Results that are significantly different from those for control mice (P < 0.05) are indicated by asterisks.

The ability of IL-6- and iNOS-deficient mice to mount an effective immune response against C. trachomatis contrasts with findings in other systems where these molecules were critical to host resistance. IL-6 KO mice infected with L. monocytogenes, a facultative intracellular bacterium, were unable to control bacterial replication within the spleen and liver and succumbed to fatal listeriosis as early as 4 days postinfection, apparently due to defective recruitment of neutrophils to the site of infection (15). Neutrophil depletion has also been shown to delay clearance of chlamydial infections but not to alter the final outcome of infection (3), suggesting that an early neutrophil response may be less critical to the resolution of Chlamydia infections within mucosal epithelium than to the management of Listeria infections within hepatocytes and macrophages. The iNOS pathway for generating toxic nitrogen intermediates has been identified as a critical component in the intracellular killing of several macrophage pathogens (2, 10, 30) and has been implicated in the elimination of Chlamydia as well (23). However, as shown herein, mice lacking the iNOS enzyme displayed normal or even accelerated clearance of this organism from the genital mucosa. To explain such differences, it has been suggested that the relative contribution of the nitric oxide pathway varies according to the genetic background of the inbred strain used in each study (29, 32). Alternatively, iNOS KO mice may develop compensatory mechanisms of immunity, as demonstrated by the up-regulation of IL-12 and IL-10 after Chlamydia infection. However, since neither IL-10, IL-12, nor downstream cytokines known to be induced by IL-12 display enzymatic activities capable of substituting for the function of iNOS, it is difficult to invoke compensation as an explanation for the efficiency of clearance in these mutant mice. It is more likely that the effector mechanisms required for elimination of C. trachomatis from mucosal epithelial cells do not involve the nitric oxide pathway.

Genital tract pathology in normal and mutant mice.

Chlamydial infection can lead to the development of substantial uterine pathology in many individuals, resulting in infertility and/or pelvic inflammatory disease (38). Histologic evaluation of MoPn-infected genital tissues from control mice or from mice deficient in iNOS or IL-6 revealed a similar pathologic profile in all samples in that mononuclear infiltrates had subsided but a moderate degree of hydrosalpinx remained by 47 days postinfection (data not shown). iNOS KO mice exhibited a trend toward development of more severe hydrosalpinx which may be related to the increased production of IL-12 in these animals; however, this observation must be confirmed in a larger group of mice.

In summary, these data argue against a critical role for IL-6 or the nitric oxide effector pathway in the expression of immunity to C. trachomatis MoPn in the murine host. Previous studies revealed that host immunity was also unaffected by induced deficiencies in major histocompatibility complex class I expression (34), antibody production (42), or IL-4 (35). Conversely, interference with major histocompatibility complex class II expression, CD4+ T-cell development (34), or IL-12 (35) dramatically inhibited chlamydial clearance. IFN-γ was not required for elimination of MoPn infection from genital tract epithelium but appeared to be critical in preventing macrophage-mediated dissemination of Chlamydia (35). It is possible, therefore, that the role of the nitric oxide effector pathway varies according to the cellular target of infection. For example, iNOS may serve a greater role in elimination of bacteria from the macrophage than from mucosal epithelial cells (11). Ultimately, host control over infection with Chlamydia may depend on several factors, including: (i) the effector pathways available in distinct target cells, (ii) the relative susceptibility of different chlamydial strains to those effector molecules, and (iii) the genetic background of the host as it affects the induction of type 1 versus type 2 T-cell-mediated immunity (20). Given the critical role of CD4+ type 1 T cells in this system, it will be interesting to examine the possible effector function in genital tract clearance of cytotoxic CD4+ T-cell-mediated apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Rick Race for extraction of tail DNA and to Robert Evans and Gary Hettrick for graphic illustrations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams L B, Hibbs J B J, Taintor R R, Krahenbuhl J L. Microbiostatic effect of murine-activated macrophages for Toxoplasma gondii: role for synthesis of inorganic nitrogen oxides from l-arginine. J Immunol. 1990;144:2725–2729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony L S D, Morrissey P J, Nano F E. Growth inhibition of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain by IFN-γ-activated macrophages is mediated by reactive nitrogen intermediates derived from L-arginine metabolism. J Immunol. 1992;148:1829–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barteneva N, Theodor I, Peterson E M, de la Maza L M. Role of neutrophils in controlling early stages of a Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4830–4833. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4830-4833.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckerman K P, Rogers H W, Corbett J A, Schreiber R D, McDaniel M L, Unanue E R. Release of nitric oxide during the T cell-independent pathway of macrophage activation. J Immunol. 1993;150:888–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernad A, Kopf M, Kulbacki R, Welch N, Koehler G, Gutierrez-Ramos J C. Interleukin-6 is required in vivo for the regulation of stem cells and committed progenitors of the hematopoietic system. Immunity. 1994;1:725–731. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boockvar K S, Granger D L, Poston R M, Maybodi M, Washington M K, Hibbs J B, Kurlander R L. Nitric oxide produced during murine listeriosis is protective. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1089–1100. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.1089-1100.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bromander A K, Ekman L, Kopf M, Nedrud J G, Lycke N Y. IL-6-deficient mice exhibit normal mucosal IgA responses to local immunizations and Helicobacter felis infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:4290–4297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cain T K, Rank R G. Local Th1-like responses are induced by intravaginal infection of mice with the mouse pneumonitis biovar of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1784–1789. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1784-1789.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chai Z, Gatti S, Toniatti C, Poli V, Bartfai T. Interleukin (IL)-6 gene expression in the central nervous system is necessary for fever response to lipopolysaccharide or IL-1β: a study on IL-6-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1996;183:311–316. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan J, Tanaka K, Carroll D, Flynn J, Bloom B R. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on murine infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:736–740. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.736-740.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen B, Stout R, Campbell W F. Nitric oxide production: a mechanism of Chlamydia trachomatis inhibition in interferon-gamma-treated RAW264.7 cells. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;14:109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cobb J P, Danner R L. Nitric oxide and septic shock. JAMA. 1996;275:1192–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotter T W, Ramsey K H, Miranpuri G S, Poulsen C E, Byrne G I. Dissemination of Chlamydia trachomatis chronic genital tract infection in gamma interferon gene knockout mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2145–2152. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2145-2152.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cressman D E, Greenbaum L E, DeAngelis R A, Ciliberto G, Furth E E, V. P, R T. Liver failure and defective hepatocyte regeneration in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Science. 1996;274:1379–1383. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalrymple S A, Lucian L A, Slattery R, McNeil T, Aud D M, Fuchino S, Lee F, Murray R. Interleukin-6-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Listeria monocytogenes infection: correlation with inefficient neutrophilia. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2262–2268. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2262-2268.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding A H, Nathan C F, Stuehr D J. Release of reactive nitrogen intermediates and reactive oxygen intermediates from mouse peritoneal macrophages. Comparison of activating cytokines and evidence for independent production. J Immunol. 1988;141:2407–2412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doherty T M, Sher A. Defects in cell-mediated immunity affect chronic, but not innate, resistance of mice to Mycobacterium avium infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:4822–4831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fehr T, Schoedon G, Odermatt B, Holtschke T, Schneemann M, Bachmann M F, Mak T W, Horak I, Zinkernagel R M. Crucial role of interferon consensus sequence binding protein, but neither of interferon regulatory factor 1 nor of nitric oxide synthesis for protection against murine listeriosis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:921–931. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauldie J, Richards C, Baumann H. IL-6 and the acute phase reaction. Res Immunol. 1992;143:755–759. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(92)80018-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guler M L, Jacobson N G, Gubler U, Murphy K M. T cell genetic background determines maintenance of IL-12 signaling. J Immunol. 1997;159:1767–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henttinen T, Levy D E, O. S, Hurme M. Activation of the signal transducer and transcription (STAT) signaling pathway in a primary T cell response: critical role for IL-6. J Immunol. 1995;155:4582–4587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Igietseme J U. The molecular mechanism of T-cell control of Chlamydia in mice: role of nitric oxide. Immunology. 1996;87:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Igietseme J U. Molecular mechanism of T-cell control of Chlamydia in mice: role of nitric oxide in vivo. Immunology. 1996;88:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Igietseme J U, Uriri I M, Hawkins R, Rank R G. Integrin-mediated epithelial-T cell interaction enhances nitric oxide production and increased intracellular inhibition of Chlamydia. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;59:656–662. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.5.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs P, Radzioch D, Stevenson M M. In vivo regulation of nitric oxide production by tumor necrosis factor alpha and gamma interferon, but not by interleukin-4, during blood stage malaria in mice. Infect Immun. 1996;64:44–49. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.44-49.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James S L, Glaven J. Macrophage cytotoxicity against schistosomula of Schistosoma mansoni involves arginine-dependent production of reactive nitrogen intermediates. J Immunol. 1989;143:4208–4212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolb H, Kolb-Bachofen V. Nitric oxide: a pathogenetic factor in autoimmunity. Immunol Today. 1992;13:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90118-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kushima Y, Hama T, Hatanaka H. Interleukin-6 as a neurotrophic factor for promoting the survival of cultured catecholaminergic neurons in a chemically defined medium from fetal and postnatal rat midbrains. Neurosci Res. 1992;13:267–280. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(92)90039-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laubach V E, Shesely E G, Smithies O, Sherman P A. Mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase are not resistant to lipopolysaccharide-induced death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10688–10692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liew F Y, Millott S, Parkinson C, Palmer R M J, Moncada S. Macrophage killing of Leishmania parasite in vivo is mediated by nitric oxide from l-arginine. J Immunol. 1990;144:4794–4797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lotz M. Interleukin-6: a comprehensive review. Cancer Treatment Res. 1995;80:209–233. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1241-3_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacMicking J D, Nathan C, Hom G, Chartrain N, Fletcher D S, Trumbauer M, Stevens K, Xie Q-W, Sokol K, Hutchinson N, Chen H, Mudgett J S. Altered responses to bacterial infection and endotoxic shock in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Cell. 1995;81:641–650. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyaard L, Hovenkamp E, Otto S A, Miedema F. IL-12-induced IL-10 production by human T cells as a negative feedback for IL-12-induced immune responses. J Immunol. 1996;156:2776–2782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison R P, Feilzer K, Tumas D B. Gene knockout mice establish a primary protective role for major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted responses in Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4661–4668. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4661-4668.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perry L L, Feilzer K, Caldwell H D. Immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis is mediated by T helper 1 cells through IFN-γ-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol. 1997;158:3344–3352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramsay A J, Husband A J, Ramshaw I A, Bao S, Matthaei K I, Koehler G, Kopf M. The role of interleukin-6 in mucosal IgA antibody responses in vivo. Science. 1994;264:561–563. doi: 10.1126/science.8160012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salkowski C A, Barber S A, Detore G R, Vogel S N. Differential dysregulation of nitric oxide production in macrophages with targeted disruptions in IFN regulatory factor-1 and -2 genes. J Immunol. 1996;156:3107–3110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schachter J. Pathogenesis of chlamydial infections. Pathol Immunopathol Res. 1989;8:206–220. doi: 10.1159/000157149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scharton-Kersten T M, Yap G, Magram J, Sher A. Inducible nitric oxide is essential for host control of persistent but not acute infection with the intracellular pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1261–1273. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seguin M C, Klotz F W, Schneider I, Weir J P, Goodbary M, Slayter M, Raney J J, Aniagolu J U, Green S J. Induction of nitric oxide synthase protects against malaria in mice exposed to irradiated Plasmodium berghei infected mosquitoes: involvement of interferon γ and CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:353–358. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su H, Caldwell H D. CD4+ T cells play a significant role in adoptive immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the mouse genital tract. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3302–3308. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3302-3308.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su H, Feilzer K, Caldwell H D, Morrison R P. Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection of antibody-deficient gene knockout mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1993–1999. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.1993-1999.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vouldoukis I, Riveros-Moreno V, Dugas B, Ouaaz F, Becherel P, Debre P, Moncada S, Mossalayi M D. The killing of Leishmania major by human macrophages is mediated by nitric oxide induced after ligation of the FcɛRII/CD23 surface antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7804–7808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]