Abstract

The role of Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin B (STb) in neonatal porcine diarrhea caused by enterotoxigenic E. coli was examined by comparing adherent isogenic strains with or without STb. The cloned STb gene (in the plasmid pRAS1) was electroporated into a nonenterotoxigenic strain (226M) which expresses the F41 adhesin. Strain 226M pRAS1 adhered and expressed STb in vivo, causing fluid secretion in ligated ileal loops in neonatal pigs. Although strain 226M pRAS1 caused very mild diarrhea in some orally inoculated neonatal pigs, the weight loss in these pigs was similar to that caused by the parental strain without STb. We conclude that STb does not significantly contribute to diarrhea caused by enterotoxigenic E. coli in neonatal pigs.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains cause diarrhea in humans and animals by colonizing the small intestine and producing enterotoxins which cause fluid secretion. Adherence is mediated by filamentous surface structures called pili, fimbriae, or adhesins. A variety of antigenic types of adhesins are expressed by ETEC strains that cause diarrhea in pigs, including K88, K99, 987P, and F41. The E. coli enterotoxins are classified based on their thermal stability and are broadly divided into heat-labile enterotoxins (LTI and LTII) and heat-stable enterotoxins (STa and STb). The E. coli STa enterotoxins have been further subdivided into STaP, which is associated with porcine ETEC strains, and STaH, which is found in human ETEC strains. Adherence and enterotoxin expression are both required for ETEC strains to cause diarrhea (18).

The STb enterotoxin is prevalent in E. coli strains isolated from pigs with diarrhea but is rarely found in E. coli strains isolated from humans or cattle (6, 7, 11–13). ETEC strains that express STb isolated from humans have been reported, but these strains were not associated with diarrhea (7). In porcine ETEC strains, STb is the most prevalent enterotoxin identified; however, STb+ strains frequently express another enterotoxin, either LT or STaP (13). Additionally, strains that are only STb+ rarely hybridized with DNA probes for one of the known adhesins of porcine ETEC strains (3). E. coli strains that contain only STb and no other enterotoxin have been isolated from pigs, but these strains frequently lack known adhesins and are nonpathogenic (1, 8). Thus, confirmation of a specific role for STb in porcine diarrhea caused by ETEC strains has been complicated by the presence of other enterotoxin genes or the lack of a known ETEC adhesin in most isolates that express only STb.

In this study, we investigated the role of STb in ETEC-mediated diarrhea in neonatal pigs. We constructed an adherent strain that expressed only STb and isogenic control strains containing a recombinant plasmid encoding STaP or the cloning vector alone. These strains were examined for adherence and in vivo expression of enterotoxins in ligated ileal loops. The strains were also examined for pathogenicity by oral inoculation of neonatal pigs.

Strain construction.

Strain 226M was used as a host for pBR322 or recombinant plasmids encoding STb (pRAS1) or STaP (pCH4). Strain 226M is an adherent, nontoxigenic mutant of ETEC strain 431 that has lost a plasmid encoding K99 and STaP but retained the chromosomal genes for F41 (2). Strain 226M colonizes the ileum but causes very mild diarrhea and minimal weight loss in neonatal pigs (2). Strain 234M was also used as a host for pRAS1. Strain 234M is an independent mutant of strain 431 that has lost the genes encoding K99 (by deletion) but retained the STaP gene and F41 genes (2). Strain 234M, like wild-type strain 431, colonizes the ileum, expresses STaP, and causes severe diarrhea and significant weight loss in neonatal pigs (2). Strain 123 is a nontoxigenic, nonadherent control strain that has been described previously (16, 20). Strain 1790 is a nonadherent strain which expresses only STb (20).

The plasmid pRAS1 is pBR322 with a 1.1-kb HindIII fragment insert containing the STb gene and has been described previously (19). The plasmid pCH4 is pBR322 with a 1.7-kb PstI fragment containing the STaP gene subcloned from pRIT10036 (9, 14, 15). The 1.7-kb PstI fragment containing the STaP gene was first cloned into pUC18 and then subcloned as a BamHI-HindIII fragment into pBR322.

Isolated plasmid DNA was electroporated into strain 226M or 234M with a gene pulser and pulse controller (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) set at 2,500 V, 25 μF of capacitance, and 200 Ω of resistance. Ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was used to select transformants, and ampicillin-resistant colonies were screened for the recombinant plasmids carrying the gene for enterotoxin STb (pRAS1) or STaP (pCH4) by colony blot hybridization with specific DNA probes (13–15).

In vivo enterotoxin expression and adherence.

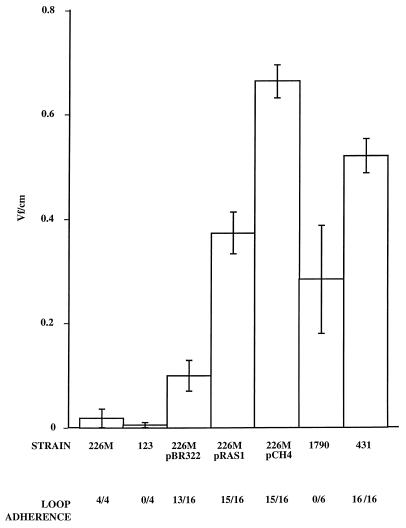

Ligated ileal loops in neonatal pigs were used to confirm that derivatives of strain 226M containing cloned genes for STaP and STb would adhere and express enterotoxin in vivo. Caesarian-derived, colostrum-deprived, neonatal pigs less than 1 day old were anesthetized, and a series of ileal loops were created. The loops were each approximately 6 cm long and separated by 3-cm interloops. Each loop was inoculated with 3 × 108 CFU of one of the strains. Soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma), which prevents degradation of STb (20, 21), was included in some loops. The pigs were kept at 35°C and given butorphanol tartrate (Torbugesic; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, Iowa) to relieve postsurgical discomfort. At 6 h postinoculation, the pigs were sacrificed and necropsied. The fluid volume and length of each loop were recorded. The loops were fixed in formalin and processed for histopathology. Adherence was determined by microscopic examination of stained sections for bacterial layers. Figure 1 shows the amount of fluid accumulated in ligated ileal loops in neonatal pigs at 6 h following inoculation with the indicated strains. Strain 1790, which is nonadherent and expresses only STb enterotoxin, was used as a control for STb expression and did not cause fluid secretion in the absence of TI as has been shown previously (20, 21). There was no difference in fluid secretion in loops inoculated with any of the adherent strains with or without trypsin inhibitor; these data were combined to obtain the mean final fluid volumes per centimeter shown in Fig. 1. All of the strains containing either the STaP or STb enterotoxin gene caused significantly more fluid secretion than the nontoxigenic control strain (strain 123) or strain 226M with or without the cloning vector pBR322 (P < 0.05; Student’s t test). Strain 226M containing the cloned STb (226M pRAS1) or STaP (226M pCH4) gene adhered as well as the adherent, nontoxigenic (strains 226M and 226M pBR322) and wild-type (strain 431) parents.

FIG. 1.

Mean fluid accumulation per cm (± standard error of the mean) and bacterial adherence for the indicated strains in ligated ileal loops made in neonatal pigs. Fluid accumulation is expressed as final loop volume per centimeter (Vf/cm). Loop adherence is expressed as number of loops with adherent bacteria per number of loops examined. The number of loops for each strain is the same for fluid accumulation measurements and adherence determinations.

Oral inoculation of neonatal pigs.

Caesarean-derived, colostrum-deprived neonatal pigs were orally inoculated to compare the virulence of strain 226M pRAS1 (STb+) with that of the nontoxigenic parent strain. Neonatal pigs were housed in isolation at 35°C and given an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of serum, but they were not fed or given water. Pigs less than 8 h old were weighed and orally inoculated with 1010 CFU of one of the strains. At 18 h following inoculation, the pigs were weighed again, examined for diarrhea, and necropsied, and samples of ileum were collected for bacteriology and histopathology as previously described (2). Strains 226M, 226M pCH4 (STaP+), and 226M pBR322 were used as controls. The pigs’ weight changes and the number of pigs with diarrhea for each of the strains used are shown in Table 1. Strain 226M pCH4 (STaP+) caused severe diarrhea and weight loss in all inoculated pigs, similar to the weight loss and diarrhea seen in pigs inoculated with the wild-type parent, strain 431 (2). However, strain 226M pRAS1 (STb+) caused only mild diarrhea with weight loss that was not significantly different (P < 0.05; Student’s t test) from the weight loss caused by the nontoxigenic strain 226M or by 226M containing the cloning vector, pBR322. Table 1 also shows that strain 226M pRAS1 colonized the ileum, adhered, and grew as well in vivo as strain 226M. Despite the severe diarrhea and weight loss caused by strain 226M pCH4, this strain did not colonize as well as strain 226M or 226M pRAS1.

TABLE 1.

Incidence of diarrhea, weight change, and colonization in neonatal pigs following oral inoculation with various strains

| Strain | No. of pigs | No. of pigs with diarrhea | Mean % wt change (± SEM)a | Log CFUb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSB | TSB + Amp | Adherencec | ||||

| 226M F41+ Tox− | 12 | 4 | −6.9 (±1.2) | 8.65 | NDd | 11 |

| 226M pBR322 | 6 | 1 | −4.9 (±0.9) | 7.24 | 7.15 | 4 |

| 226M pRAS1 (STb+) | 12 | 5 | −9.2 (±1.3) | 8.44 | 8.33 | 11 |

| 226M pCH4 (STaP+) | 8 | 8 | −24.0 (±0.9) | 6.83 | 6.54 | 1 |

| 234M (STaP+) | 4 | 4 | −21.9 (±1.5) | 8.93 | NDd | 4 |

| 234M (STaP+, pRAS1 STb+) | 4 | 4 | −21.5 (±2.8) | 8.52 | 8.44 | 4 |

Mean weight change 18 h following inoculation expressed as a percentage of body weight at inoculation.

Log CFU determined for a 10-cm section of ileum. Dilutions of ileal samples were plated on tryptic soy agar media with and without ampicillin (Amp) to determine if pBR322 or the recombinant plasmids encoding STb or STaP were retained by each strain during the experiment.

Adherence, number of pigs with adherent bacteria determined by microscopic examination of stained sections of ileum.

ND, not determined.

Neonatal pigs were also inoculated with isogenic strains 234M (STaP+) and 234M pRAS1 (STaP+ and STb+) to determine if both toxins together would have a greater effect in inoculated neonatal pigs than either toxin alone. The results in Table 1 show that there was no difference in the severity of diarrhea or weight loss caused by 234M, with or without the cloned STb gene.

We found that the cloned STb gene did not significantly contribute to diarrhea caused by adherent E. coli strains in neonatal pigs. There was no difference in the incidence or severity of diarrhea in piglets inoculated with isogenic strains with STb and that in piglets inoculated with isogenic strains without STb. Strain 226M pRAS1 (STb+) caused very mild diarrhea with weight loss that was similar to that caused by the nontoxigenic parent strain 226M or by 226M containing the pBR322 vector alone (<10% weight loss). We have previously shown that, in some pigs, nontoxigenic strain 226M caused mild diarrhea with minimal weight loss similar to that in uninoculated pigs or in pigs inoculated with nonpathogenic control strains (2). Others have reported diarrhea in humans or animals following inoculation with adherent nontoxigenic strains (4, 10, 17, 18). The reason for this is not known; however, it has been suggested that intensive colonization of the small intestine might cause malabsorption which could result in mild diarrhea (17).

In orally inoculated neonatal pigs, strain 226M pCH4 (STaP+) caused severe diarrhea and weight loss similar to that seen following inoculation with the wild-type parent strain 431 (2). However, strain 226M pCH4 did not colonize as well as strain 226M or strain 226M pRAS1. The reason for this decreased colonization is not known. All the strains adhered similarly in ligated ileal loops made in neonatal pigs, suggesting that there could be differences in the bacterial growth rates in pigs orally inoculated with strain 226M containing different cloned enterotoxin genes.

The pRAS1 (STb) and pCH4 (STaP) plasmids introduced into strain 226M were relatively stable in vivo. The numbers of bacteria in 10-cm samples of ileum from piglets inoculated with 226M pRAS1 plated on media with and without ampicillin were similar (Table 1). Also, individual colonies from these plates were hybridized with a DNA probe for STb. Although there was some variation among inoculated pigs, more than 90% of the colonies retained the STb gene (data not shown).

It was very surprising that the adherent strain 226M containing pRAS1 which expressed STb did not cause severe diarrhea and weight loss in neonatal pigs. Numerous previous studies show an association of STb with E. coli isolated from pigs with diarrhea (reviewed in reference 5). However, there are very few reports of STb-only strains. Moon et al. (12) reported a K99+ STb+ strain which caused diarrhea in neonatal pigs, but this strain has subsequently been shown to also express STaP (3).

Our results show that an adherent strain that expressed only STb caused fluid secretion in the ilea of neonatal pigs, but it is not clear why this STb+ strain did not increase the severity of diarrhea in orally inoculated neonatal pigs. It is possible that the secretion caused by STb has a shorter duration or is less than that caused by STa. It is also possible that STb acts more slowly than STa in causing fluid accumulation which eventually leads to diarrhea. The confirmation of these interesting possibilities requires additional experiments. However, our results show that by 6 h postinoculation, ligated ileal loops inoculated with 226M pRAS1 (STb+) had significant fluid accumulation. It is not clear why the fluid accumulation did not result in diarrhea and significant weight loss in the 18 h following oral challenge with the same strain. Perhaps the secretion caused by STb is reabsorbed elsewhere in the small intestine or the large intestine, while STa secretions are not reabsorbed.

In these experiments, we specifically only examined the role of STb in ETEC diarrhea in neonatal pigs. It is possible that STb plays a role in diarrhea caused by ETEC in older, weaned pigs. Older pigs are resistant to adherence by the parent strain 431, which expresses K99 and F41 adhesins (16). Therefore, the F41+ strain, 226M, used in this study could not be used to determine the role of STb in diarrhea caused by ETEC strains in weaned pigs. Experiments to determine if STb contributes to ETEC strains that cause diarrhea in weaned pigs will require construction of isogenic strains that, while similar to those described here, will colonize older pigs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Broes A, Fairbrother J M, Larivière S, Jacques M, Johnson W M. Virulence properties of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O8:KX105 strains isolated from diarrheic piglets. Infect Immun. 1988;56:241–246. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.241-246.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casey T A, Moon H W. Genetic characterization and virulence of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli mutants which have lost virulence genes in vivo. Infect Immun. 1990;58:4156–4158. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.4156-4158.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casey, T. A., and R. A. Schneider. Unpublished data.

- 4.Dougan G, Sellwood R, Maskell D, Sweeney K, Liew F Y, Beesley J, Hormaeche C. In vivo properties of a cloned K88 adherence antigen determinant. Infect Immun. 1986;52:344–347. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.344-347.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubreuil J D. Escherichia coli STb enterotoxin. Microbiology. 1997;143:1783–1795. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echeverria P, Seriwatana J, Patamaroj U, Moseley S L, McFarland A, Chityothin O, Chaicumpa W. Prevalence of heat-stable II enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in pigs, water, and people at farms in Thailand as determined by DNA hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:489–491. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.4.489-491.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Echeverria P, Seriwatana J, Taylor D N, Tirapat C, Chaicumpa W, Rowe B. Identification by DNA hybridization of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in a longitudinal study of villages in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:124–130. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairbrother J M, Broes A, Jacques J, Lariviere S. Pathogenicity of Escherichia coli O115: “V165” strains isolated from pigs with diarrhea. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50:1029–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lathe R, Hirth P, DeWilde M, Harford N, Lecocq J P. Cell-free synthesis of enterotoxin of E. coli from a cloned gene. Nature. 1980;284:473–474. doi: 10.1038/284473a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine M M, Kaper J B, Black R E, Clements M L. New knowledge on the pathogenesis of bacterial enteric infections as applied to vaccine development. Microbiol Rev. 1983;47:510–550. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.4.510-550.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mainil J G, Bex F, Jacquemin E, Pohl P, Couturier M, Kaeckenbeeck A. Prevalence of four enterotoxin (STaP, STaH, STb, and LT) and four adhesin subunit (K99, K88, 987P and F41) genes among Escherichia coli isolates from cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1990;51:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moon H W, Kohler E M, Schneider R A, Whipp S C. Prevalence of pilus antigens, enterotoxin types, and enteropathogenicity among K88-negative enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli from neonatal pigs. Infect Immun. 1980;27:222–230. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.1.222-230.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon H W, Schneider R A, Moseley S L. Comparative prevalence of four enterotoxin genes among Escherichia coli isolated from swine. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:210–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moseley S L, Huq I, Alim A R M A, So M, Samadpour-Motalebi M, Falkow S. Detection of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli by DNA colony hybridization. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:892–898. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.6.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moseley S L, Echeverria P, Seriwatana J, Tirapat C, Chaicumpa W, Sakuldaipeara T, Falkow S. Identification of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli by colony hybridization using three enterotoxin gene probes. J Infect Dis. 1982;145:863–869. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.6.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Runnels P L, Moon H W, Schneider R A. Development of resistance with host age to adhesion of K99+Escherichia coli to isolated intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1980;28:298–300. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.1.298-300.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlager T A, Wanke C A, Guerrant R L. Net fluid secretion and impaired villous function induced by colonization of the small intestine by nontoxigenic colonizing Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1337–1343. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1337-1343.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith H W, Linggood M A. Observations on the pathogenic properties of the K88, hly, and ent plasmids of Escherichia coli with particular reference to porcine diarrhoea. J Med Microbiol. 1971;4:467–485. doi: 10.1099/00222615-4-4-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whipp S C, Moseley S L, Moon H W. Microscopic alterations in jejunal epithelium of 3-week-old pigs induced by pig-specific, mouse-negative, heat-stable Escherichia coli enterotoxin. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:615–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whipp S C. Protease degradation of Escherichia coli heat-stable, mouse-negative, pig-positive enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2057–2060. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2057-2060.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whipp S C. Intestinal responses to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli heat-stable toxin b in non-porcine species. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:734–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]