SUMMARY

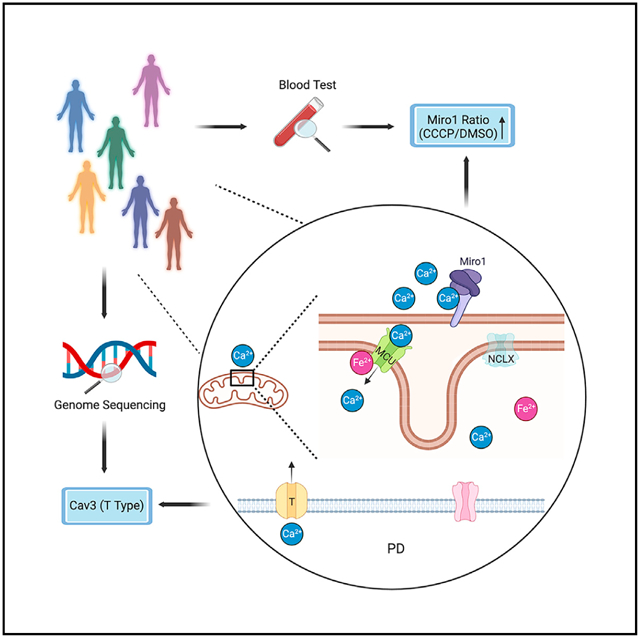

Dysregulated iron or Ca2+ homeostasis has been reported in Parkinson’s disease (PD) models. Here, we discover a connection between these two metals at the mitochondria. Elevation of iron levels causes inward mitochondrial Ca2+ overflow, through an interaction of Fe2+ with mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU). In PD neurons, iron accumulation-triggered Ca2+ influx across the mitochondrial surface leads to spatially confined Ca2+ elevation at the outer mitochondrial membrane, which is subsequently sensed by Miro1, a Ca2+-binding protein. A Miro1 blood test distinguishes PD patients from controls and responds to drug treatment. Miro1-based drug screens in PD cells discover Food and Drug Administration-approved T-type Ca2+-channel blockers. Human genetic analysis reveals enrichment of rare variants in T-type Ca2+-channel subtypes associated with PD status. Our results identify a molecular mechanism in PD pathophysiology and drug targets and candidates coupled with a convenient stratification method.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

Bharat et al. identify a mitochondrial inside-out Fe2+−Ca2+ signal in PD pathophysiology. This signal identifies multiple drug targets and candidates, coupled with a convenient stratification method for PD.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a leading cause of disability. The dopamine (DA)-producing neurons in the substantia nigra are the first to die in PD patients. A bottleneck that hinders our ability to effectively detect and treat PD may be the presence of highly heterogeneous genetic backgrounds and risk factors among different patients. Functional studies have pointed to multiple “cellular risk elements” for PD, such as mitochondrial damage, lysosomal dysfunction, immune system activation, neuronal calcium mishandling, and iron accumulation.1–10 These distinct genetic and cellular risk factors may confer individual heterogeneity in disease onset, but also suggest that there are networks and pathways linking these “hubs” in disease pathogenesis. Identifying their connections could be crucial for finding a cure for PD.

Mitochondria are the center of cellular metabolism and communication. Ions such as Ca2+ and iron are not only essential for diverse mitochondrial functions but can be stored inside the mitochondria to maintain cellular ionic homeostasis. Ion channels and transporters in the plasma and mitochondrial membranes coordinate for ion uptake, transport, and storage. Ca2+ enters the cell via voltage- or ligand-gated Ca2+ channels across the cell surface. Inside the cell, Ca2+ can be taken up by mitochondria through the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) channel, VDAC, and the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) channel, mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU),11 and extruded into the cytosol through the IMM transporter, NCLX.12 MCU is part of a multimeric holocomplex consisting of multiple regulatory subunits, such as essential MCU regulator (EMRE), mitochondrial calcium uptake 1 (MICU1), MICU2, and MCUb,13–15 and the MCU complex can be substituted.16 For iron transport, iron bound carrier proteins such as transferrin deliver iron into the cell through endocytosis and intracellular iron can be taken up by mitochondria via several IMM transporters.17 Although individually, dysregulation of iron or Ca2+ homeostasis has been reported in PD models, their mechanistic link and contribution to disease susceptibility remain elusive. In this work, we harness the power of combining human genetics, cellular and in vivo models, and patient’s tissues, and identify a mitochondrial inside-out Fe2+-Ca2+-Miro1 axis in PD.

RESULTS

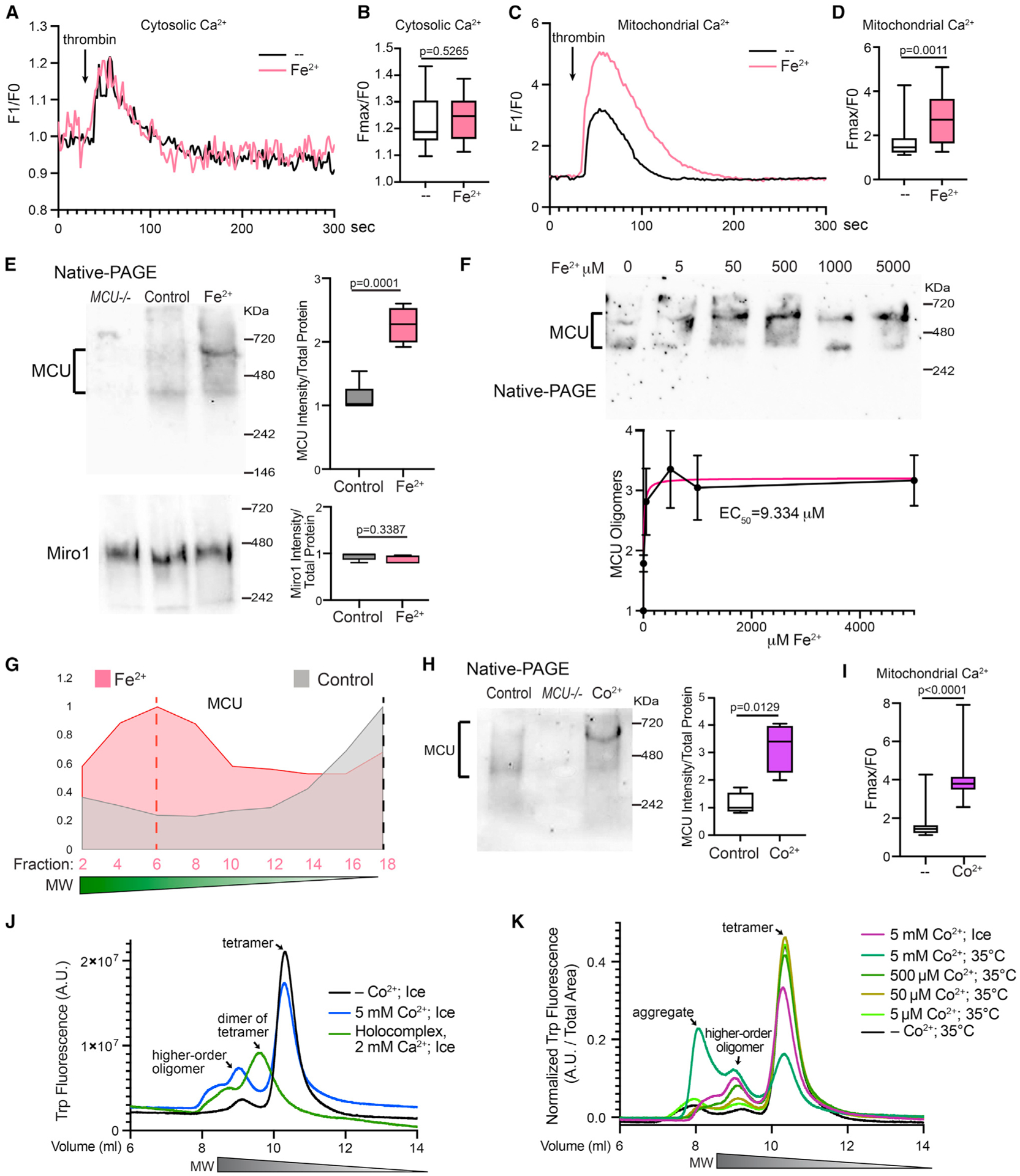

Iron promotes the MCU complex assembly

The MCU’s Ca2+-import ability can be modulated by the elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ and intramitochondrial oxidants.14,18 We investigated whether the elevation of iron levels, a hallmark of PD,9 could also regulate MCU activity. It has been shown that following the stimulation of G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) agonist, the clearance of cytosolic Ca2+ is mediated by MCU.18–20 To investigate the relation of MCU and iron, we treated HEK293T cells with Fe2+, stimulated these cells the next day with the GPCR agonist, thrombin, and measured cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ levels with live Calcium Green and Rhod-2 staining, respectively. We found that thrombin triggered intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and elevation, which was comparable between Fe2+-treated and mock control cells (Figures 1A and 1B). However, mitochondria in Fe2+-treated cells sustained a significantly larger Ca2+ elevation after thrombin stimulation, as compared with mock control (Figures 1C and 1D). These results indicate that iron promotes the mitochondrial Ca2+-import ability.

Figure 1. Iron promotes MCU oligomerization.

(A–D) HEK cells were treated with 500 μM Fe2+ for 22 h, stimulated with thrombin, and mitochondrial (Rhod-2) and cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Calcium Green) were measured. (A and C) Representative Ca2+ traces. (B and D) Quantification of the peak fluorescent intensity (Fmax) normalized to the baseline (F0) within each cell. n = 20 cells from four independent coverslips.

(E) HEK cells were treated with 5 mM Fe2+ for 22 h, run in Native-PAGE, and blotted. Right: Qualification of the band intensity normalized to the total protein amount measured by a BCA assay. n = 5.

(F) Similar to (E), but with a range of Fe2+ concentrations added to the media. n = 4. Data point shows mean ± SEM.

(G) Elution profiles of MCU from SEC samples.

(H) HEK cells were treated with 500 μM Co2+ for 22 h and run in Native-PAGE. n = 4.

(I) HEK cells treated with 500 μM Co2+ for 22 h were stimulated with thrombin, and mitochondrial Ca2+ levels (Rhod-2) were measured. n = 20 cells from four independent coverslips. (B), (D), (E), (H), and (I) Two-tailed Welch’s t Test.

(J and K) Fluorescence-detection SEC profiles. See also Figure S1.

Because MCU oligomerization affects its localization and potentially its Ca2+-uptake ability,14,18 we next explored whether iron altered the assembly of the MCU complex. Native-PAGE is a sensitive method to determine the overall form and amount of a multimeric native protein. The human MCU oligomer bands from HEK cells migrated between 400 and 700 KDa in Native-PAGE (Figure 1E).11,21,22 Importantly, we found that Fe2+ treatment for 22 h resulted in an increase in the total intensity of the MCU oligomer bands and appeared to shift some bands upward (Figure 1E), indicating the formation of higher-order oligomers. Miro1, an OMM protein, also oligomerized and migrated as a single band around 480 kDa in Native-PAGE, which was not significantly affected by Fe2+ treatment (Figure 1E). The half maximal effective concentration of Fe2+ added to the media to cause the MCU response was 9.334 μM (Figure 1F). We confirmed that HEK cells were morphologically healthy under all concentrations and no significant cell death was observed (Figure S1A). To corroborate the Native-PAGE result, we performed an alternative method to differentiate protein complexes based on their molecular weight (MW)-size exclusion chromatography (SEC). Protein complexes with higher MW are eluted faster than those with lower MW. Detecting MCU from cell lysates using SEC has been successfully shown.15,18,21 We found that Fe2+ treatment shifted the MCU elution peak to the earlier fractions of higher-order oligomers compared with mock control (Figures 1G and S1B; anti-MCU was validated in Figure S1C). As a positive control for this method, we treated cells with H2O2 for 10 min and found the shift of the MCU elution peak to the earlier fractions (Figure S1D), consistent with previous studies also using SEC.18 In contrast, the elution pattern of Miro1 was largely unaltered by any of these treatments (Figure S1E). These data indicate that iron shifts the MCU complexes to higher-order oligomers and enlarges the total number of these complexes.

To dissect the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS)18 in contributing to the Fe2+-triggered MCU function as observed above, we treated HEK cells with an antioxidant, vitamin C (VitC),23 which has no iron-chelating ability,24 or an iron chelator, deferiprone (DFP),25 together with Fe2+, and measured MCU oligomerization and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. DFP, but not VitC, lowered the MCU oligomer band intensity and mitochondrial Ca2+ import in the presence of Fe2+ (Figures S1F and S1G), indicating that ROS might have a nominal effect on Fe2+-mediated MCU regulation, at least in this experimental setting.

We attempted to reconstitute the phenomenon of the Fe2+-triggered increase of MCU oligomerization in vitro. However, a fast speed of Fe2+ oxidation caused precipitation of purified MCU protein. To circumvent this problem, we used an Fe2+ mimic, Co2+ ion.26 The data of Co2+ might inform us about properties of Fe2+. We confirmed that Co2+ behaved similarly as Fe2+ in our functional assays in HEK cells: Co2+ treatment increased MCU oligomerization detected by Native-PAGE (Figure 1H) and enhanced the mitochondrial Ca2+-uptake ability following thrombin application (Figure 1I), just like Fe2+ (Figures 1C–1E). We then conducted fluorescence-detection SEC using purified human MCU protein,14 and found that Co2+ caused the formation of higher-order oligomers of MCU (Figure 1J). As a positive control for this approach, we reproduced the elution peak of the dimer of tetramer of the MCU holocomplex caused by Ca2+ addition in vitro (Figure 1J).14 These results demonstrate that the Fe2+ mimic, Co2+, increased MCU oligomerization in vitro. Collectively, Fe2+ and its mimic Co2+ promote the formation of MCU higher-order oligomers and enhance the mitochondrial Ca2+-uptake activity.

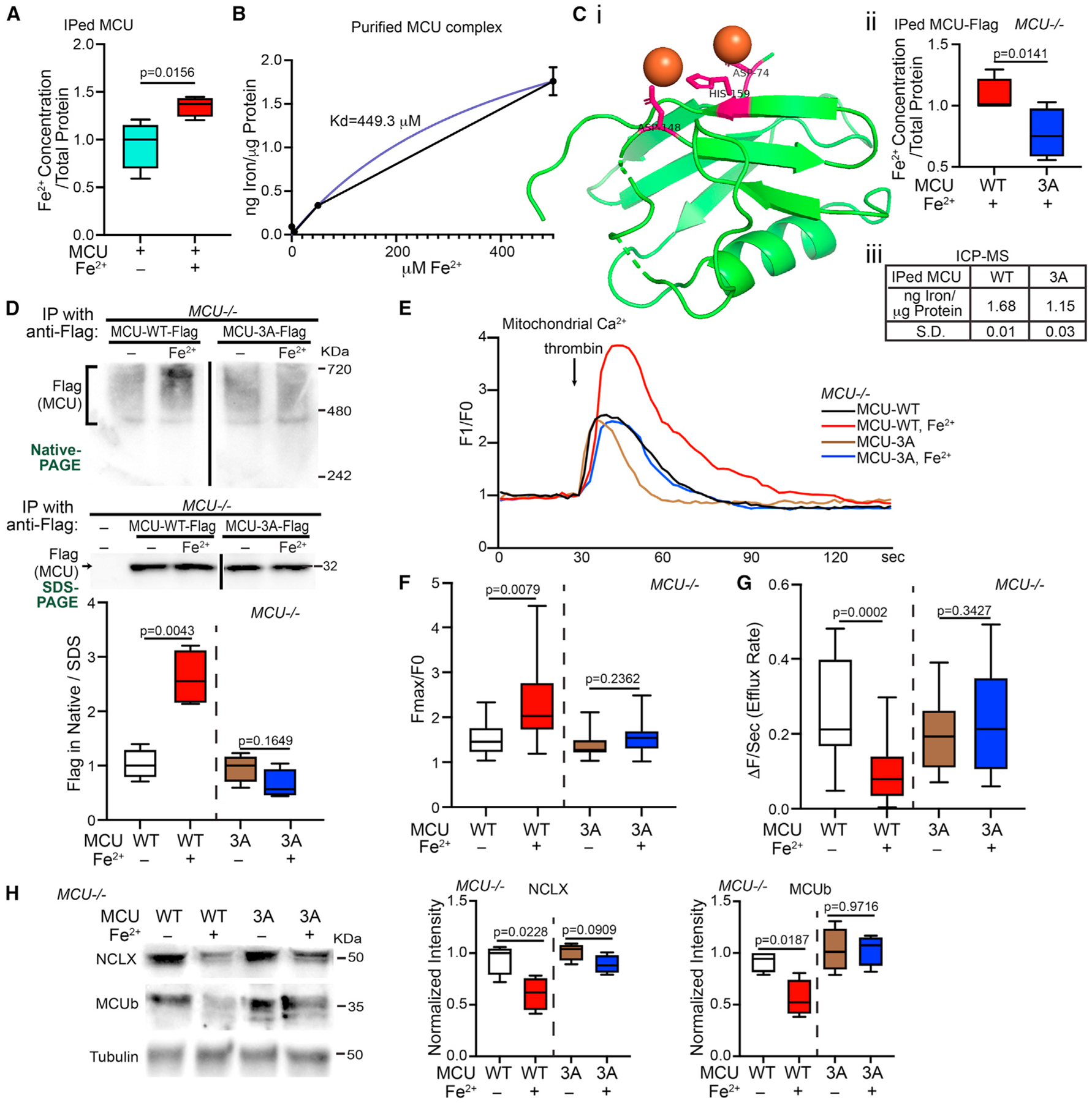

Fe2+ binds to the MCU complex to promote its oligomerization and channel activity

Our in vitro result in Figure 1J suggested that Co2+ bound to MCU to cause the formation of higher-order oligomers. We further confirmed that Co2+ altered MCU oligomerization and thermostability in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1K).

We hypothesized that Fe2+ also bound to MCU to increase its oligomerization. To explore this possibility, we immunoprecipitated (IP) endogenous MCU from HEK cells and detected the iron concentrations in the IP samples. We found significantly more Fe2+ ions pulled down with MCU when HEK cells were treated with Fe2+ (Figure 2A). We next examined whether MCU directly bound to Fe2+ by an in vitro binding assay. To minimize protein precipitation caused by Fe2+ oxidation, we performed an alternative to the thermal shift-SEC experiment with Co2+ shown in Figure 1K, which could take hours to complete. We applied Fe2+ to the purified MCU complex (MCU, MICU1, MICU2, ERME)14 for about 5 min and after washing immediately measured iron levels in the complex by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). We found that the MCU complex bound to Fe2+ in vitro with a Kd of 449.3 μM (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. MCU Binds to Fe2+.

(A) HEK cells were treated with or without 500 μM Fe2+ for 21 h, then IPed with anti-MCU, and Fe2+ concentrations in the IP samples were detected (normalized to the total protein amount). Two-tailed paired t test. n = 4.

(B) Different concentrations of Fe2+ were added to the purified MCU complex in vitro and after wash the total iron level in the complex was detected by ICP-MS. Mean ± SEM. n = 3.

(Ci) Structural visualization of the matrix domain of MCU (green) bound to Fe2+ (orange) via these sites (pink) generated by PyMol. (Cii) MCU−/− HEK cells transfected as indicated were treated with 500 μM Fe2+ for 20 h, then IPed with anti-Flag, and Fe2+ concentrations in the IP samples were detected. Two-tailed paired t test. n = 4. (Ciii) ICP-MS measurement of the total iron level in IPed MCU-Flag from cells as in (Cii), normalized to the total protein amount. n = 3.

(D) Representative blots of IP with anti-Flag using cell lysates as indicated, run in Native- or SDS-PAGE. n = 4.

(E) MCU−/− HEK cells transfected as indicated and treated with or without 500 μM Fe2+ for 22 h were stimulated with thrombin, and mitochondrial Ca2+ levels (Rhod-2) were measured. Representative Ca2+ traces.

(F and G) Based on traces like in (E), the peak fluorescent intensity normalized to baseline (F) or efflux rate (G) is quantified. n = 17 cells from four independent coverslips.

(H) Cells as in (D) and (E) were lysed and blotted. Normalized to tubulin. n = 4. (D–H) Two-tailed Welch’s t test. Relative to “MCU-WT” or “MCU-3A” without treatment.

We next searched for amino acid residues in the matrix domain of MCU (PDB: 5KUE) predicted to bind to Fe2+ using an in silico program (http://bioinfo.cmu.edu.tw/MIB/),27,28 and found three amino acids: 74D, 148D, and 159H (Figure 2Ci). The latter two residues were also predicted to bind to Co2+. We mutated these three sites to Alanine (named “MCU-3A”). If MCU bound to Fe2+ via some of these sites, MCU-3A should reduce their binding. Indeed, we detected significantly fewer Fe2+ in the immunoprecipitate of Flag-tagged MCU-3A, as compared with MCU-WT, expressed from HEK cells without endogenous MCU (MCU−/−) treated with Fe2+ (Figure 2Cii). We confirmed this result by ICP-MS (Figure 2Ciii). Thus, MCU may bind to Fe2+ through some of these sites.

To determine whether blocking of MCUs binding to Fe2+ was sufficient to eliminate the Fe2+-triggered oligomerization of MCU, we expressed MCU-WT or MCU-3A in MCU−/− HEK cells to prevent the interference of endogenous MCU, treated these cells with Fe2+, and ran IPed MCU in Native-PAGE. As expected, MCU-3A abolished MCU’s response to Fe2+ treatment: the MCU oligomer band intensity was no longer increased (Figure 2D). We then live imaged mitochondrial Ca2+ dynamics, as described in Figure 1, in these cells. We consistently observed a larger mitochondrial Ca2+ elevation following thrombin stimulation in MCU-WT-transfected HEK cells treated with Fe2+ as compared with no Fe2+ treatment, and MCU-3A blunted the peak increase (Figures 2E and 2F). Of note, MCU-3A-expressing cells maintained normal functions of MCU (Figures 2D–2H), suggesting no negative impact on cells by these mutations. In addition, ROS similarly promoted the oligomerization of MCU-WT and MCU-3A (Figure S1H), consistent with that the cysteine residues for oxidation18 remain intact in both proteins. Thus, ROS might have a negligible role in the difference between MCU-WT and 3A triggered by Fe2+ seen in Figures 2D–2H. Altogether, our results show that Fe2+ promotes MCU oligomerization and its channel activity through binding to MCU.

Iron reduced NCLX and MCUb protein levels in a manner dependent on MCU channel activity

We next examined additional membrane proteins that may assist MCU function using HEK cells. By detecting total protein levels using western blotting, we found a reduction in only MCUb and NCLX but not the other 12 proteins examined, including MCU monomers, when cells were treated with Fe2+ for 20–22 h (Figure S2), demonstrating selective protein responses without widespread toxicity at this time point (Figure S1A). MCUb is an inhibitor of MCU,15 and NCLX is an IMM exchanger believed to be for mitochondrial Ca2 extrusion.12,29 The reduction of both proteins could contribute to the phenotype of mitochondrial Ca2+ overload upon Fe2+ treatment observed earlier (Figures 1C and 1D).

We explored the possibility that the reduction of NCLX and MCUb was secondary to MCU activity and resultant Ca2+ overload. We took advantage of the MCU-3A-expressing MCU−/− cells, which eliminated MCU’s Fe2+-binding and Fe2+-elicited channel activity (Figure 2). By measuring the Ca2+ extrusion rate we found that Fe2+ treatment slowed the efflux rate in MCU-WT-expressing MCU−/− cells, which was prevented by MCU-3A (Figure 2G). This result suggests that the Fe2+-triggered efflux delay may depend on Ca2+ overload caused by increased MCU activity. We then immunoblotted NCLX and MCUb protein from these cells. We found again the reduction of NCLX and MCUb in MCU-WT-expressing MCU−/− cells upon Fe2+ treatment and their protein levels were restored in MCU-3A-expressing cells (Figure 2H). Hence, these findings indicate that mitochondrial Ca2+ overload upon Fe2+ elevation is the primary reason for the reduction of NCLX and MCUb levels.

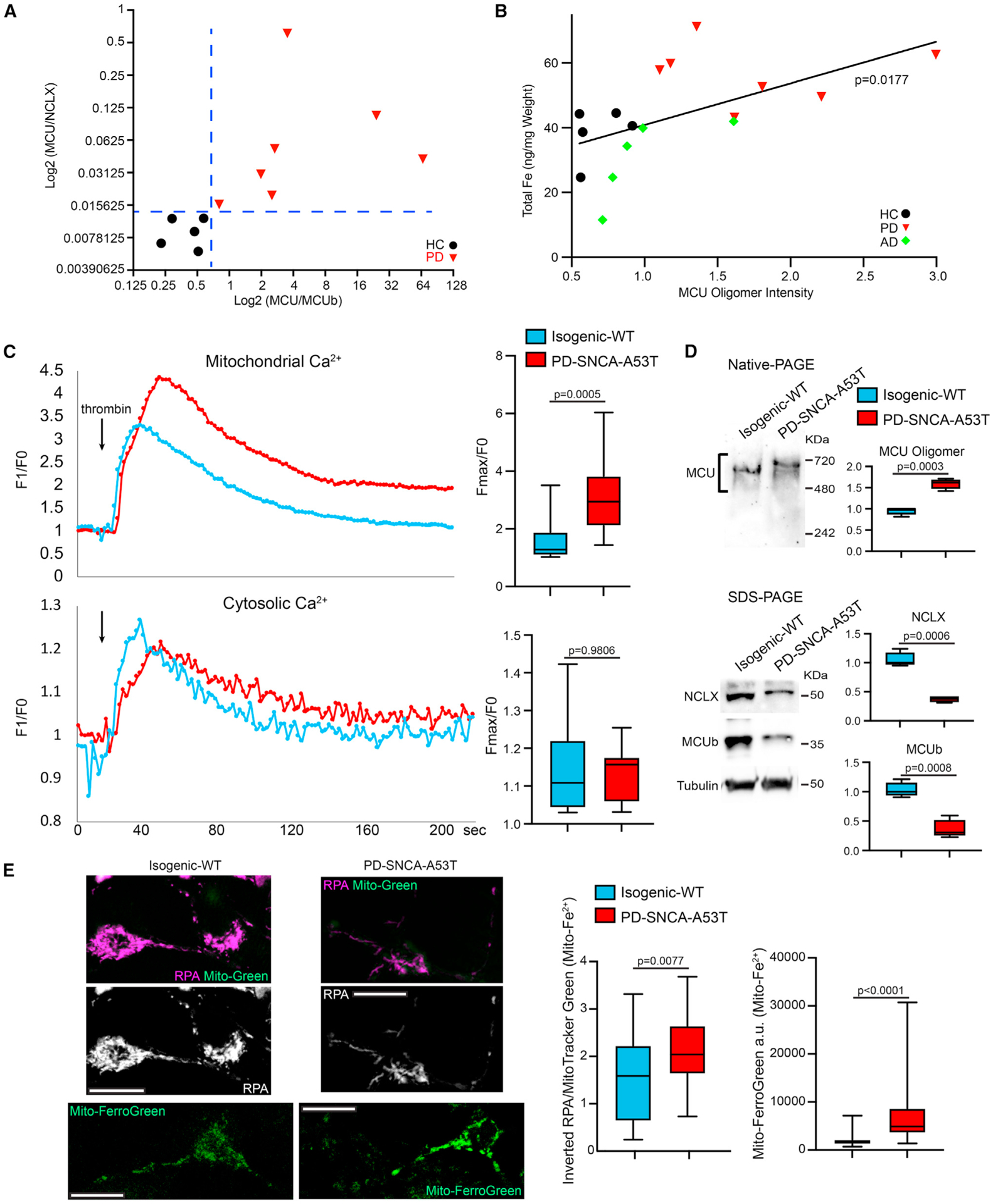

PD postmortem brains and neurons mirror Fe2+-treated HEK cells

Our data so far have shown that artificially increasing iron levels causes mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation by promoting MCU activity. We examined this mechanism in pathophysiological PD models without the need of adding exogenous iron to the media. We first investigated postmortem brains of people with sporadic PD without a family history (Table S1). We homogenized the frontal cortex, where iron elevation in PD patients had been reported before,30 and ran the brain lysate in Native- or SDS-PAGE. Consistent with previous studies, MCU, NCLX, and MCUb were detected in the human brain.8,31 We found that the PD group (seven patients) clustered and separated from the healthy control group (five), with higher intensity of the MCU oligomer bands in Native-PAGE and lower intensity of both the NCLX and MCUb bands in SDS-PAGE (Figures 3A and S3A), similar to the observations in HEK cells treated with Fe2+ (Figures 1 and S2). This unique clustering was not observed in the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) group (five patients) (Figure S3A). The total iron level in each brain fraction, measured by ICP-MS, was positively correlated with the corresponding band intensity of MCU oligomers in Native-PAGE (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. PD models mirror Fe2+-treated HEK cells.

(A) Postmortem brains were run in Native- or SDS-PAGE and blotted. Blots and details are in Figure S3A. HC: healthy control.

(B) The total iron level (y axis) in each brain fraction was measured by ICP-MS (normalized to wet weight, average of three repeats), and plotted with the band intensity of MCU oligomers in Native-PAGE (x axis) from the same brain fraction. Linear fit.

(C) iPSC-derived neurons were stimulated with thrombin and mitochondrial (Rhod-2) and cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Calcium Green) were measured in the somas. Left: Representative Ca2+ traces. n = 15 cell bodies from three independent coverslips.

(D) iPSC-derived neurons were lysed and blotted as indicated. Normalized to the total protein amount. n = 4.

(E) Left: Confocal single section images of live neurons as in (C) and (D) stained with RPA (quenched by Fe2+) and MitoTracker Green (Mito-Green), or Mito-FerroGreen (stains Fe2+). Scale bars, 10 μm. Middle: Quantification of the RPA fluorescent intensity in each soma from inverted images normalized to MitoTracker Green, a membrane-potential-independent dye whose intensity was similar between control and PD neurons (p = 0.2524). n = 26 (WT) and 28 (PD) cell bodies from three coverslips. Right: Quantification of the Mito-FerroGreen fluorescent intensity in each soma subtracting background. n = 55 cell bodies from three coverslips. Two-tailed Welch’s t test. See also Figure S3.

We next employed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from one familial patient (PD-SNCA-A53T) with the A53T mutation in SNCA (encodes α-synuclein) and its isogenic wild-type control (isogenic-WT).32–35 We differentiated iPSCs to neurons expressing tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme for DA synthesis as previously described.32–35 These patient-derived neurons display increased expression of endogenous α-synuclein.33 We stimulated these neurons with thrombin and measured cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ levels as in Figure 1. We found very similar Ca2+ dynamic pattern in PD neurons as in HEK cells treated with Fe2+: PD neurons suffered from more mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation after thrombin stimulation, as compared with isogenic control (Figure 3C). We next ran the neuronal lysates in Native- and SDS-PAGE. We again observed an upward shift of the MCU oligomer bands and an increase in the total MCU band intensity in Native-PAGE indicating the formation of higher-order oligomers, and a reduction of the intensity of NCLX and MCUb bands in SDS-PAGE in PD neurons compared with control (Figure 3D). We also discovered a significant increase in the mitochondrial Fe2+ levels detected by RPA and Mito-FerroGreen staining in PD neurons (Figure 3E). The phenotypes of mitochondrial Fe2+ and Ca2+ were observed in older neurons as well (day 40, Figure S3B). Collectively, our results demonstrate a positive correlation of iron levels with MCU oligomerization and its channel activity in PD patient-derived neurons and postmortem brains.

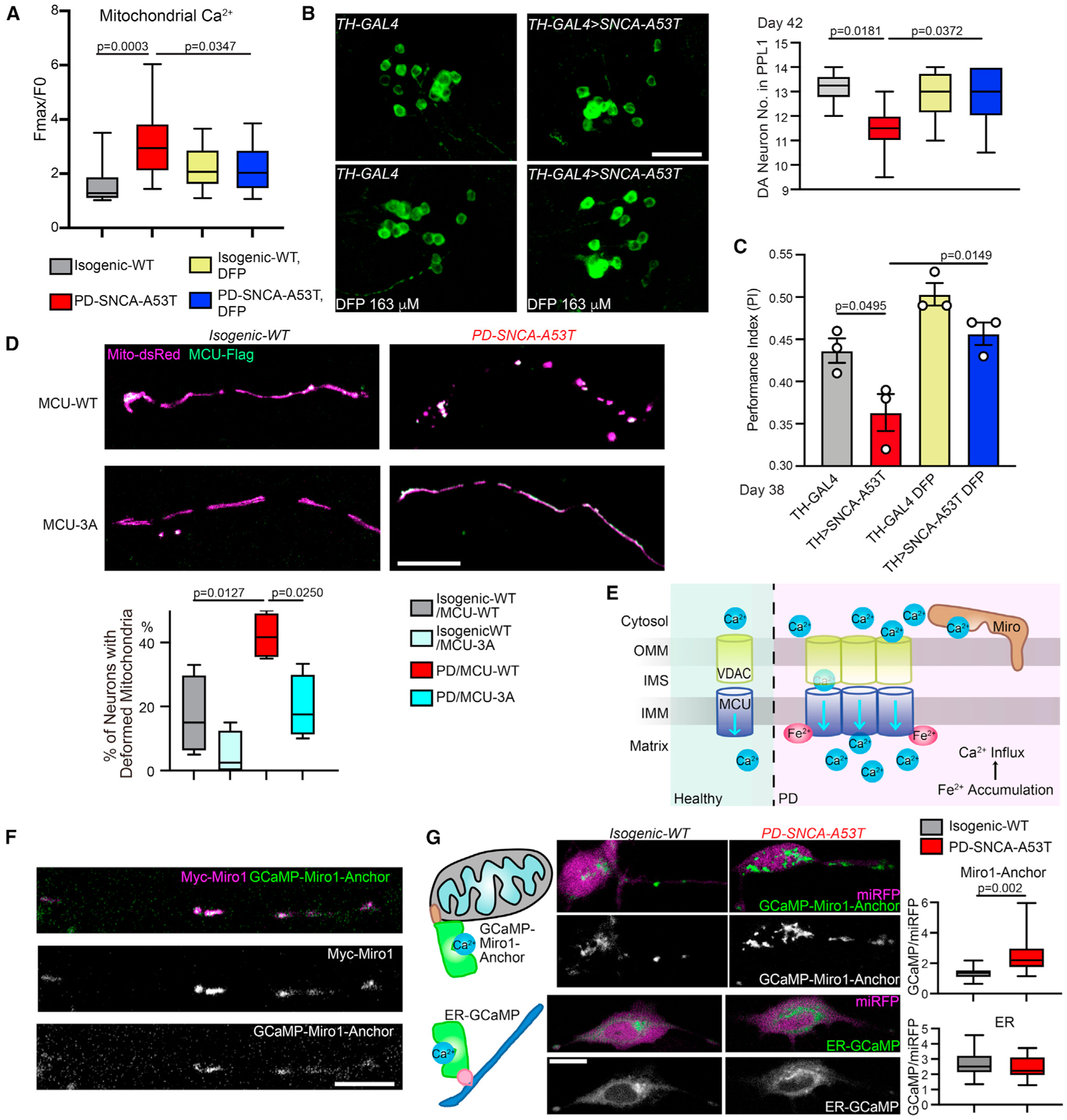

Iron functions upstream of calcium to mediate phenotypes of PD neurons

Our findings suggested the possibility that the elevation of iron levels in PD caused mitochondrial Ca2+ overload by the binding of MCU with Fe2+ (Figures 1, 2, and 3). To test this hypothesis, we reduced iron levels in PD neurons described in Figure 3 with DFP and found that DFP significantly lowered mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation following thrombin stimulation (Figure 4A), demonstrating a causal relation between iron elevation and Ca2+ overload in the mitochondria. These PD neurons are more vulnerable to mitochondrial stressors. The treatment of the complex III inhibitor, Antimycin A, at 10 μM for 6 h caused acute neuronal cell death leading to the increase of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) signals in neurons derived from this PD patient, but not in isogenic control neurons (Figure S3C).33–35 We found that pretreatment with DFP prevented cell death (Figure S3C). We validated these findings in neurons differentiated from additional iPSC lines, including those from two sporadic patients (PD-S1, PD-S2; no family history) and two healthy controls (HC-1, HC-2),32–34 and an isogenic pair containing a mutant line (Jax-SNCA-A53T) where SNCA-A53T was made in iPSCs of a healthy donor and an isogenic control (Jax-Rev) by reverting SNCA-A53T back to wild type (STAR Methods). We consistently observed key features shown earlier: mitochondrial Fe2+ and stimulated-Ca2+ levels were elevated (Figures S3D and S3E), and DFP prevented mitochondrial Ca2+ overload (Figure S3D) and stressor-induced cell death (Figure S3C) in these PD-related lines. In order to cross-validate the neuroprotection of DFP in vivo without the need of adding a stressor, we fed DFP to a fly model of PD, which expressed the pathogenic human α-synuclein protein with the A53T mutation (α-syn-A53T) in DA neurons driven by TH-GAL4.33–35 These flies exhibit PD-relevant phenotypes such as age-dependent locomotor decline and DA neuron loss.33–35 In the protocerebral posterior lateral 1 (PPL1) cluster of the fly brain, the DA neuron number typically ranges between 11 and 14, but this number is reduced in PD flies. We found that feeding PD flies with DFP restored the DA neuron number in aged fly brains and improved the climbing ability (Figures 4B and 4C). Collectively, our results show that iron functions upstream of calcium and mediates neurodegeneration in multiple PD models.

Figure 4. Iron functions upstream of calcium in PD neurons.

(A) Similar to Figure 3, iPSC-derived neurons, with or without treatment of 100 μM DFP for 24 h, were stimulated with thrombin, and mitochondrial Ca2+ (Rhod-2) was measured. n = 15 cell bodies from three independent coverslips. Control data without DFP treatment are the same as in Figure 3C.

(B) The DA neuron number (average of both sides) was counted in the PPL1 cluster. Drug treatment was started from adulthood (day 1). Scale bar, 20 μm. n = 6, 9, 8, 7 (from left to right) flies.

(C) Drug treatment was started from embryogenesis. n = 35, 33, 40, 34 flies (from left to right), three independent experiments.

(D) Representative confocal images of neurites transfected as indicated. Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantification of the percentage of total neurons with deformed mitochondria (defined as a neuron without any mitochondrion in neurites >2.5 μm in length). n = 4 coverslips. (A) and (D) One-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey test.(B) and (C) Two-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey test.

(E) Schematic representation of iron-triggered mitochondrial calcium influx in PD.

(F) A PD-SNCA-A53T iPSC-derived neuron was transfected as indicated and immunostained with anti-Myc. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(G) Confocal live images of neurons transfected as indicated. Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantification of the intensity of GCaMP6f normalized to miRFP670 within the same cell body. n = 15 cell bodies from three coverslips. Two-tailed Welch’s t test. See also Figure S3.

We next utilized the Fe2+-resistant MCU mutant, MCU-3A (Figure 2), to block extra Fe2+ binding in PD neurons. While expressing MCU-WT in PD neurons caused mitochondrial deformation including shortening, fragmenting, and swelling, probably due to substantial iron-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ overload,36 MCU-3A completely prevented this phenotype (Figure 4D). As mentioned earlier, ROS should similarly oxidize both MCU-WT and 3A proteins18 (Figure S1H) and impact those PD neurons. These results suggest that eliminating MCU’s binding to Fe2+ renders protection for mitochondria.

Together, our data from both HEK cells and PD models demonstrate a pathological mechanism whereby iron accumulation inside the mitochondria causes inward Ca2+ overflow via a direct binding of Fe2+ with MCU and the resultant augmentation of MCU activity (Figure 4E).

Local OMM calcium dysregulation is sensed by Miro1 in Parkinson’s models

We reasoned that the enlarged Ca2+ ion influx through MCU in PD models could alter local Ca2+ dynamics and balance at the OMM (Figure 4E). This subdomain-scale Ca2+ change might be sensed by a nearby OMM protein. Miro1 is a Ca2+-binding protein on the OMM facing the cytosol, and in close proximity to mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ channels.2,37–39 Thus, Miro1 may directly encounter Ca2+ flux going through mitochondria and sense even spatially confined Ca2+ concentration changes. To explore this possibility, we swapped the cytosolic portion of Miro1 with the fluorescent Ca2+ sensor, GCaMP6f, while leaving Miro1’s C-terminal transmembrane and tail domain intact to allow proper OMM localization,35 named GCaMP-Miro1-Anchor. A cytosolic-expressing miRFP670 gene was constructed in the same vector for background control. This Ca2+ sensor should detect Ca2+ ions at the subdomains of the OMM where Miro1 is located. We confirmed that GCaMP-Miro1-Anchor was colocalized with Miro1 in human neurons (Figure 4F). The intensity of GCaMP-Miro1-Anchor was increased showing elevated local Ca2+ concentrations in live PD neurons compared with isogenic control, while the intensity of a Ca2+ sensor located to the cytosolic face of the ER membrane was unchanged (Figure 4G). This increase in the GCaMP-Miro1-Anchor intensity was not caused by increased mitochondrial volume because the fluorescent intensity of MitoTracker Green, a membrane-potential-independent dye, was comparable between control and PD neurons (Figure 3E). Importantly, inhibiting the MCU activity by RU36040 reduced OMM Ca2+ elevation detected by GCaMP-Miro1-Anchor in PD neurons (Figure S3F). These data suggest that enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ influx could raise spatially restricted Ca2+ concentrations at the OMM and that Miro1 may serve as an ideal sensor for this change (Figure 4E).

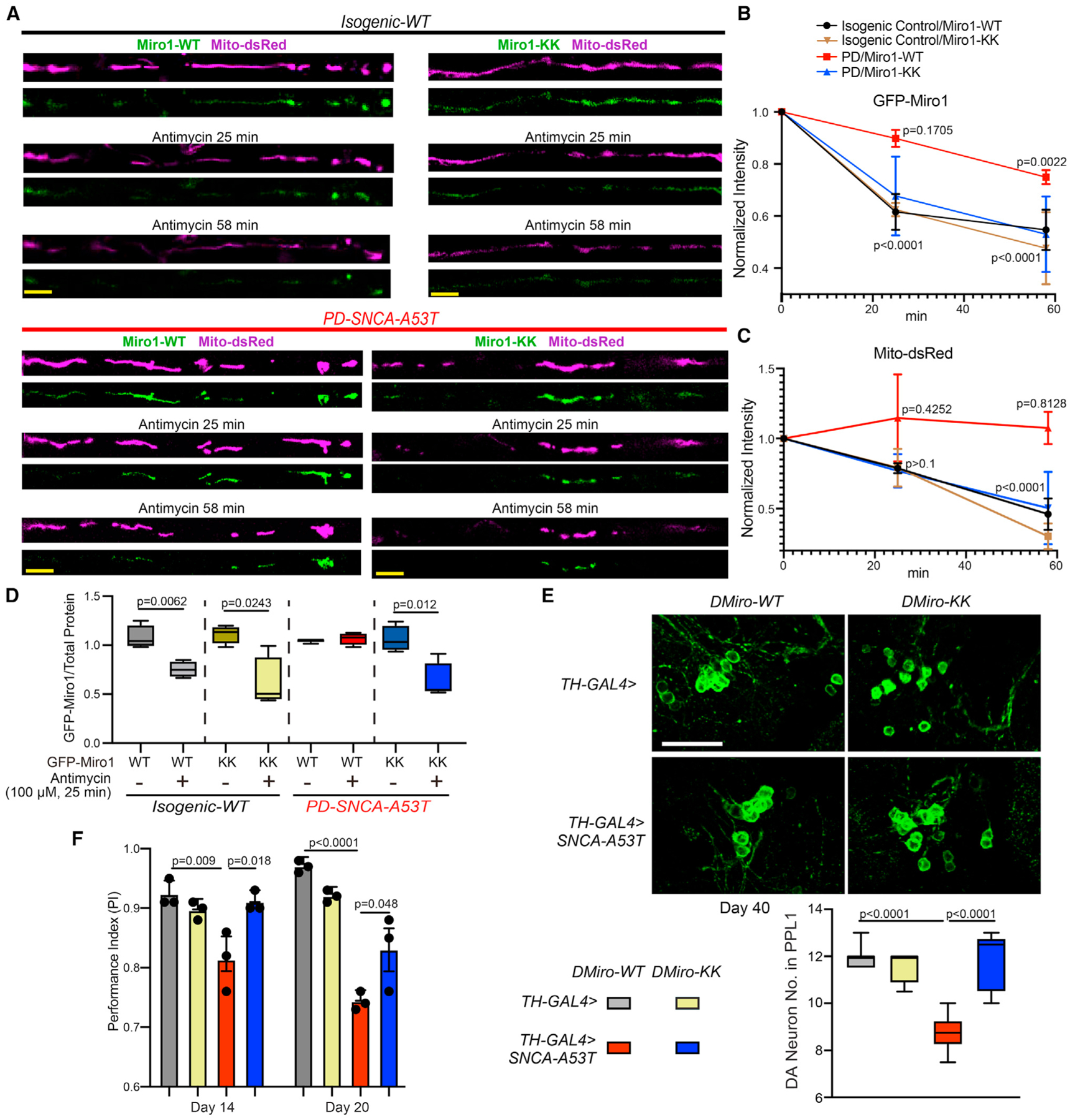

We next sought a quantitative measurement of Miro1’s Ca2+ sensitivity at the OMM, which could help us develop specific molecular markers to distinguish PD patients with OMM Ca2+ elevation. We had previously found a Miro1 phenotype in PD models and patients’ cells. We explored whether this Miro1 phenotype was a result of Miro1’s Ca2+ sensing. In a healthy cell, upon mitochondrial depolarization, Miro1 is quickly removed from the OMM and degraded in proteasomes, primed by PD-related proteins including PINK1, Parkin, and LRRK2, allowing the subsequent mitophagy.32–34,41,42 We had shown that Miro1 degradation upon mitochondrial depolarization was delayed in fibroblasts or neurons derived not only from familial PD patients with mutations in Parkin or LRRK2 but also from sporadic patients without known mutations, consequently slowing mitophagy and increasing neuronal sensitivity to stressors.32–34 The mechanism underlying this unifying Miro1 phenotype in both familial and sporadic PD patients remained undefined. To explore whether this phenotype resulted from Miro1’s Ca2+ binding, we made GFP-tagged human Miro1 protein in both the wild-type form (Miro1-WT) and in a mutant form where two point mutations were introduced in the two EF-hands of Miro1 (Miro1-KK) to block Ca2+ binding.43 We expressed GFP-tagged Miro1 (WT or KK) and Mito-dsRed that labeled mitochondria in iPSC-derived neurons from the PD patient and isogenic control, described earlier. We had previously discovered that following acute Antimycin A treatment that depolarized the membrane potential and triggered mitophagy, Miro1 and mitochondria were sequentially degraded in wild-type neurons.32–34 We observed the same mitochondrial events in isogenic control axons transfected with GFP-Miro1-WT by live imaging (Figures 5A–5C). In contrast, in PD neuron axons transfected with GFP-Miro1-WT, the degradation rates of both Miro1 and damaged mitochondria upon Antimycin A treatment were slowed (Figures 5A–5C), consistent with our previous studies.33,34 Notably, GFP-Miro1-KK significantly rescued these phenotypes in PD axons: it expedited the degradation rates to the control level (Figures 5A–5C). We validated the result of Miro1 degradation using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of GFP (Figure 5D). These data suggest that delayed Miro1 and damaged mitochondrial degradation rely on Miro1’s Ca2+ binding in PD neurons.

Figure 5. Miro senses calcium to mediate several PD relevant phenotypes.

(A) Representative still images from live Mito-dsRed and GFP-Miro1 recordings in axons of indicated genotypes, following 100 μM Antimycin A treatment. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(B and C) Degradation rate profiles of GFP-Miro1 (B) or Mito-dsRed (C) normalized to the same axonal region at 0 min. n = 5 axons (one axon per coverslip). Comparison with “0 min.” One-way ANOVA post hoc Dunnett’s test.

(D) iPSC-derived neurons were transfected as indicated and GFP-Miro1 was detected by an ELISA normalized to the total protein amount. n = 4. Two-tailed Welch’s t test within each condition.

(E) The DA neuron number. Scale bar, 20 μm. n = 7, 4, 6, 5 (from left to right).

(F) n (from left to right) = 49, 47, 39, 47 (day 14); 48, 45, 37, 44 (day 20); three independent experiments.

(E) and (F) Two-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey test. See also Figure S3.

To confirm the Miro-Ca2+ relation in vivo, we generated transgenic flies carrying T7-tagged fly Miro (DMiro)-WT or DMiro-KK. DMiro is an ortholog of human Miro1 with high sequence similarity. Both DMiro-WT and DMiro-KK were expressed at comparable levels when the transgenes were driven by the ubiquitous driver Actin-GAL4 (Figure S3G). We next crossed these transgenic flies to a fly PD model described earlier that expressed human α-syn-A53T in DA neurons driven by TH-GAL4. We found that DMiro-KK significantly rescued the phenotypes of age-dependent DA neuron loss and locomotor decline, compared with DMiro-WT (Figures 5E and 5F). This result shows that blocking DMiro’s Ca2+ binding is neuroprotective in PD flies. Altogether, we have provided evidence that Miro1 or DMiro senses Ca2+ to mediate several phenotypes in human neuron and fly models of PD.

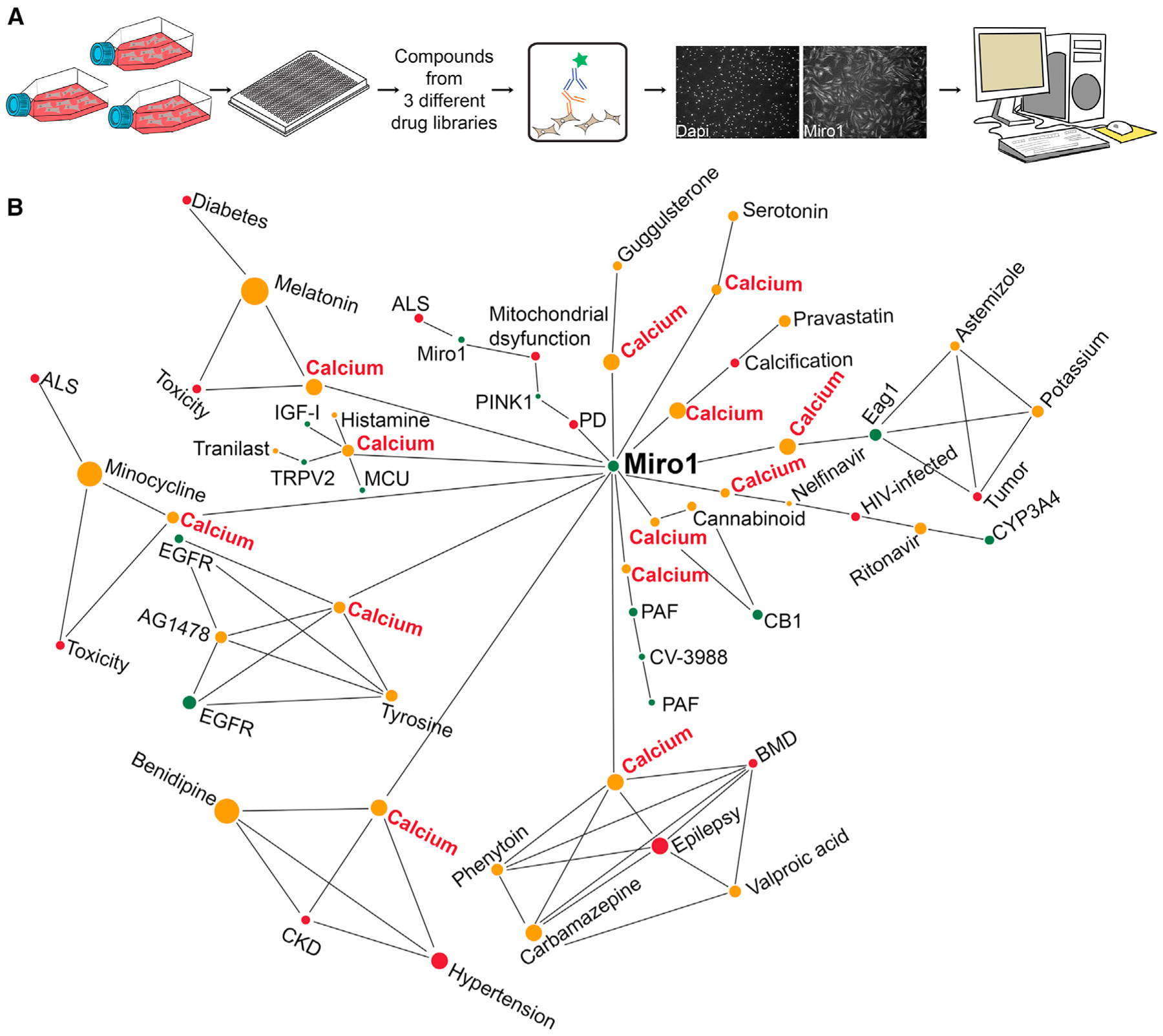

A high-content Miro1 screening assay identifies a network of Ca2+-related drug hits for PD

To further support that Miro1 was downstream of Ca2+ dysregulation in PD, we performed high-throughput (HTP) drug screens in fibroblasts from a sporadic PD patient using the Miro1 phenotype (delayed degradation upon depolarization) as a readout. If Miro1 sensed local Ca2+ elevation to become more stable on damaged mitochondria (Figures 4G and 5A–5C), we expected to see Ca2+-related drug hits to show up to promote Miro1 degradation. To this end, we established a sensitive immunocytochemistry (ICC)-based assay that was suitable for HTP screening (Figures 6A, S4, S5, and S6A; Table S2, STAR Methods). We performed the primary screens at the Stanford High-Throughput Bioscience Center (HTBC) using three drug libraries containing many compounds that have well-defined roles and targets and show efficacy to treat certain human diseases (Figure S4). Drug hits from primary screens were then retested in our own laboratory using fresh compounds at the highest screening concentration with at least four biological replicates and our confocal microscope (Figure S5). In total, we discovered 15 compounds in two independent experimental settings that reduced Miro1 protein levels following mitochondrial depolarization in PD fibroblasts (Figure S5C; Table S2).

Figure 6. HTP screens identify Ca2+-related drug hits for PD.

(A) Schematic representation of a custom-designed drug screen for Miro1 in PD fibroblasts.

(B) Pathway analysis identifies Ca2+ as a shared factor in the primary hit-Miro1 network. See also Figures S4 and S5.

Next, we performed a pathway analysis using a knowledge graph-based tool to reveal the potential cellular pathways connecting Miro1 to each hit compound. Strikingly, we discovered intracellular Ca2+ as a primary shared factor in the hit drug-Miro1 network (Figure 6B; Table S3). Two drugs, Benidipine and Tranilast, could directly inhibit plasma membrane Ca2+ channels. Benidipine is a blocker of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (L-, N-, T-type), and Tranilast has been proposed to inhibit ligand-gated Ca2+ channels (TRPV2).44 Therefore, our results confirm the importance of the Ca2+ pathway for mediating the Miro1 phenotype in PD.

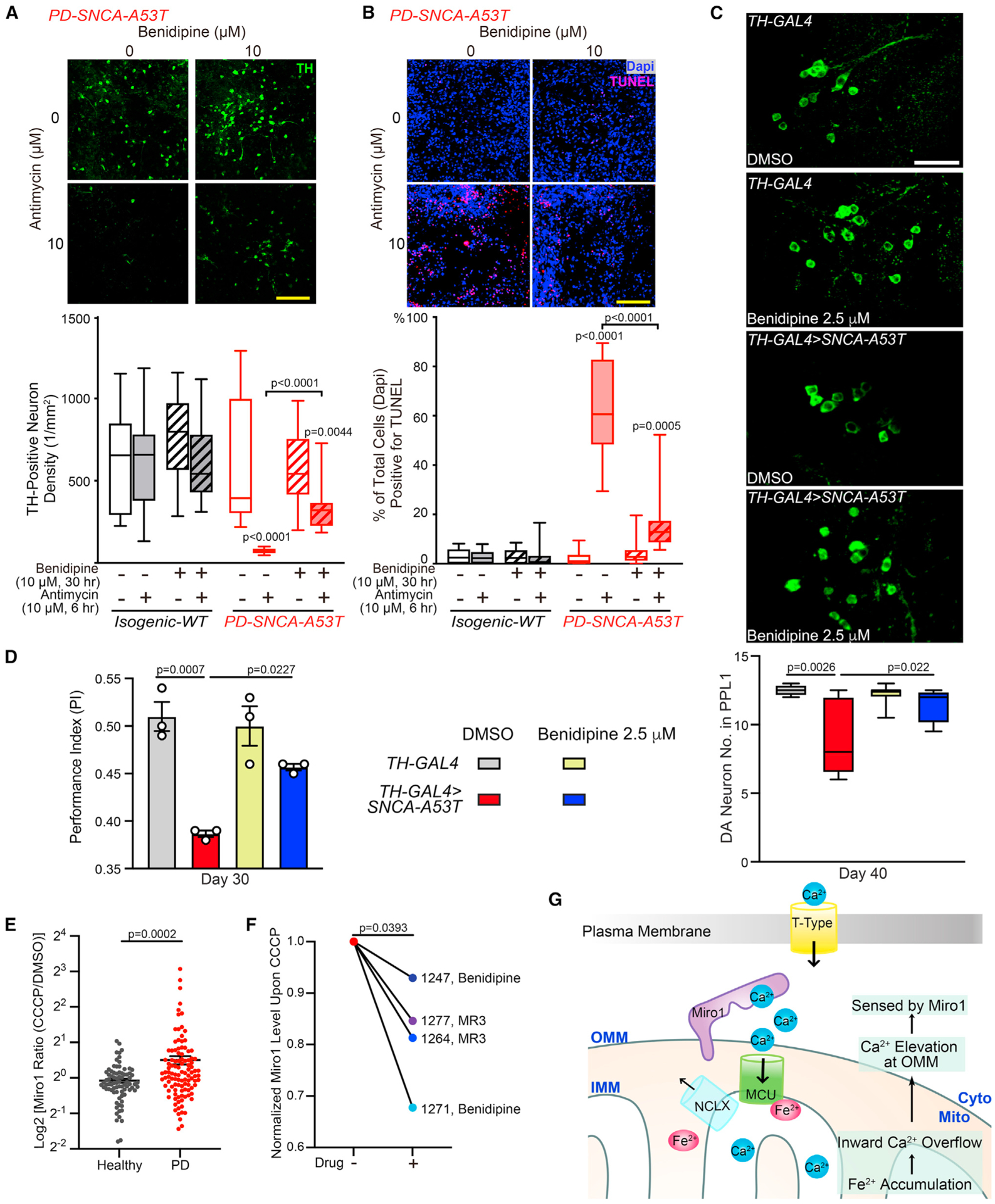

Benidipine rescues Parkinson’s-relevant phenotypes in multiple models of PD

We further validated the top hit from our screens, Benidipine, a pan-Ca2+-channel blocker. Using the same ICC method as in Figure S5, we found that Benidipine reduced Miro1 in a dose-dependent manner upon depolarization in PD fibroblasts (Figure S6B). To exclude the possibility of any artifacts caused by our ICC method, we verified our results by western blotting and observed the same rescue effect: Benidipine promoted Miro1 degradation after mitochondrial depolarization in PD fibroblasts (Figure S6C). We confirmed that Benidipine did not affect Miro1 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression detected by reverse-transcription quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) under basal and depolarized conditions in PD cells (Figure S6D). Neither did Benidipine alter the basal ATP levels (Figure S6E), nor the mitochondrial membrane potential measured by TMRM staining (Figure S6F).

We next tested Benidipine in the human neuron model of PD described in Figure 3. We confirmed that Benidipine reduced local Ca2+ elevation at the OMM detected by GCaMP-Miro1-Anchor (Figure S3F) and promoted Miro1 degradation following Antimycin A treatment in PD neurons (Figure S6G; similar to DFP). This result corroborates that delayed Miro1 removal upon depolarization reflects OMM Ca2+ elevation. Notably, treating these PD neurons with Benidipine at 10 μM for 30 h mitigated stressor-induced neuron death: the loss of TH immunostaining and increase of TUNEL staining after Antimycin A treatment33,35 were significantly rescued (Figures 7A and 7B).

Figure 7. Benidipine rescues PD relevant phenotypes.

(A and B) iPSC-derived neurons treated as indicated were immunostained with anti-TH (A) or TUNEL and Dapi (B). Scale bars, 100 μm. n = 20 images from three independent coverslips. p values are compared with the far-left bar, except indicated otherwise. One-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey test.

(C) DA neurons in the PPL1 cluster. Scale bar, 20 μm. n = 4, 6, 7, 4 (from left to right).

(D) n = 59, 57, 54, 57 flies (from left to right), three independent experiments.

(C and D) Drug treatment was started from adulthood (day 1). Two-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey test.

(E) Miro1 protein levels were measured using ELISA in PBMCs treated with DMSO or 40 μM CCCP for 6 h. Dot plot with mean ± SEM. n = 80 controls and 107 PD. Two-tailed Welch’s t test.

(F) PBMCs from four PD patients were treated with 40 μM CCCP for 6 h, or pretreated with 10 μM Benidipine or MR3 for 18 h and then with 40 μM CCCP for another 6 h, and Miro1 protein was detected using ELISA. Two-tailed paired t test.

(G) Schematic representation of this study. See also Figures S6 and S7.

In vivo, we fed Benidipine to the fly model of PD without adding any mitochondrial stressors. Importantly, feeding these flies with 2.5 μM Benidipine from adulthood prevented DA neuron loss in aged flies (Figure 7C) and improved their locomotor ability (Figure 7D). Taken together, our results show that either lowering local OMM Ca2+ levels by Benidipine or blocking Miro1’s Ca2+ binding eliminates the Miro1 defect of slower degradation upon depolarization and additional phenotypes in PD models (Figures 5, 6, 7, and S6).

A Miro1 blood test reflects PD status and responds to drug treatment

A challenge in current PD research is the lack of reliable and convenient molecular markers for patient stratification. The subset of PD patients with Ca2+ elevation at the OMM should be sensed by Miro1, and once Miro1 bound to Ca2+ it could be quantitatively measured by a proxy—the slower Miro1 response to a mitochondrial uncoupler (Figures 5, 6, 7, and S6). We next explored the potential of this Miro1 proxy as a PD marker in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). We cultured PBMCs from a healthy donor from the Stanford Blood Center (SBC) (Table S4) and depolarized the mitochondrial membrane potential using two different methods: Antimycin A plus Oligomycin,45 or CCCP. We found that both depolarizing approaches caused the degradation of Miro1 and additional mitochondrial markers in a time-dependent manner, detected by western blotting (Figures S7A and S7B), consistent with other cell types.32,34,46 These results show that Miro1 can respond to mitochondrial depolarization in healthy PBMCs, allowing us to further utilize these cells to develop a Miro1 assay for PD.

To enable high-content screening, we applied an ELISA of Miro1 (Figures S7C and S7D) to PBMCs from the same donor with a 6-h CCCP treatment. We saw a similar Miro1 response to CCCP using ELISA (SBC, Table S4) as using western blotting. The reproducibility of the result using ELISA led us to choose this method and 6-h CCCP treatment to screen a total of 80 healthy controls and 107 PD patients (Table S4). Miro1 Ratio (Miro1 protein value with CCCP divided by that with DMSO from the same person) was significantly higher in PD patients compared with healthy controls (Figure 7E; Table S4), suggesting that PBMCs from more PD patients may have Ca2+ elevation at the OMM and consequently fail to rapidly remove Miro1 from damaged mitochondria. Hence, Miro1 Ratio by our method may be used as an indicator of OMM Ca2+ changes.

To determine whether our method could be used to classify an individual into a PD or healthy group, we employed machine learning approaches using our dataset. We trained a logistic regression model to assess the impact of Miro1 Ratio on PD diagnosis, solely on its own or combined with additional demographic and clinical parameters (STAR Methods). Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) is a tool to measure motor and non-motor symptoms of PD that may reflect disease severity and progression. Using UPDRS, our model yielded an accuracy (an individual was correctly classified as with PD or healthy) of 81.2% (p < 0.000001; area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [ROC]–AUC = 0.822), and using Miro1 Ratio, the accuracy was 67.6% (p = 0.03; AUC = 0.677). Notably, if both Miro1 Ratio and UPDRS were considered, our model generated an improved accuracy of 87.8% (p = 0.02; AUC = 0.878; p = 5.736e-09 compared with UPDRS alone, paired t test on bootstrapped samples), without the interference of age or sex (STAR Methods, Figures S7E and S7F). Therefore, our results suggest that the molecular (Miro1 Ratio–OMM Ca2+ elevation) and symptomatic (UPDRS) evaluations may reveal independent information, and that combining both tests could more accurately categorize individuals with PD and measure their responses to experimental therapies.

To probe the potential utilization of this Miro1 assay in future clinical trials for stratifying patients with OMM Ca2+ dysregulation and monitoring drug efficacy, we treated PBMCs from four PD patients (Table S4) with either of the two compounds known to reduce Miro1, Benidipine (Figures 6, 7, and S4–S6) and Miro1 Reducer 3 (MR3).34,35 Miro1 protein levels upon CCCP treatment were lowered by each compound in all four patients (Figure 7F), showing that the Miro1 marker in PBMCs can respond to drug treatment. Collectively, our results suggest that Miro1 protein in blood cells may be used to aid in diagnosis and drug development.

Rare variants in T-type Ca2+ channels are associated with PD status

After dissecting the functional impairment of this Fe2+-Ca2+-Miro1 axis in PD, we explored its genetic contribution to PD. Earlier, we showed that chelating iron, blocking MCU’s binding to Fe2+, blocking Miro1’s binding to Ca2+, or preventing Ca2+ entry into the cell all alleviated Parkinson’s related phenotypes (Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7). We evaluated the genes encoding the protein targets of these approaches, which are spatially distinct and localized to three subcellular locations: (1) IMM Ca2+ channels and transporters (targeted by Fe2+), (2) the Ca2+-binding protein Miro on the OMM, and (3) plasma membrane Ca2+ channels (targeted by Benidipine and Tranilast) (Figure 7G; Table S5). By analyzing common variants within or near any of the investigated genes in GWAS reported in Nalls et al.,47 we did not observe significant association with PD clinical status. We next employed the whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data from the Accelerating Medicines Partnership–Parkinson’s Disease (AMP–PD) (1,168 control; 2,241 PD), and assessed rare non-synonymous and damaging variants using burden-based and SKATO methods. We discovered an enrichment of rare variants in selective T-type Ca2+-channel subtypes (Cav3.2, 3.3) (cell surface), Miro2 (OMM), or NCLX (IMM) associated with PD status with a nominal p value (Table S5). Notably, an SKATO Test on all variants of T-type or L-type Ca2+-channel subtypes showed a significant association with PD status of T-type channels, which survived multiple comparison correction, but not of L-type channels (Table S5). Together, our analysis unravels potential genetic predisposition of T-type Ca2+ channels to PD.

Inhibiting T-type Ca2+ channels promotes Miro1 degradation

Our discovery of the selective accumulation of rare variants in T-type Ca2+ channels associated with PD diagnosis (Table S5) prompted us to functionally validate this finding. We employed a mini drug screen using the same screening ICC assay described earlier (Figures 4 and 5) by which we discovered the non-selective pan-Ca2+-channel blocker, Benidipine. This time, we examined two L-type and three T-type Ca2+-channel blockers. Intriguingly, we again found a striking selection of T-type versus L-type channels in the connection with Miro1 in PD fibroblasts (Figure S7G): only T-type blockers promoted Miro1 degradation following depolarization, just like Benidipine. Importantly, two of these blockers, MK-899848,49 (approved by the Food and Drug Administration) and ML-218,50 were already shown in vivo safety and efficacy for treating PD-associated symptoms in humans or preclinical rodent models. By contrast, L-type blockers, including Isradipine that recently failed a phase III trial for PD,51 did not affect the Miro1 phenotype (Figure S7G).To genetically inhibit T-type Ca2+ channels, we knocked down by small interfering RNA (siRNA) the T-type subtype Cav3.2, which showed strongest association with PD diagnosis in the human genetic analysis (Table S5). Consistently, genetically reducing Cav3.2 promoted Miro1 degradation upon depolarization in PD neurons (Figure S7H). These studies implicate a benefit for clinical trials by coupling T-type channel inhibitor drugs and the Miro1 marker.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we have established a mitochondrial inside-out pathway of Fe2+-Ca2+-Miro1 dysregulation in our PD models (Figure 7G). Chelating iron, reducing Ca2+ entry into the cell, or blocking Miro1’s binding to Ca2+ is each neuroprotective (Figures 4, 5, and 7). Hence, this ionic axis may be important for PD pathogenesis and can be leveraged for better detecting and treating the disease.

The Miro1 marker could help address unmet needs in PD clinical care. There is a high rate of misdiagnosis of PD because there is no definitive molecular marker to confirm the disease.52 The lack of disease-modifying therapies is partially due to no reliable pharmacodynamic biomarkers in clinical trials.34,53 Our Miro1 blood test has a potential to serve both as a patient stratification tool and a pharmacodynamic marker for drug discovery. The exciting link between T-type channel blockers and Miro1 in PD suggests this Miro1 blood test may be used in clinical trials for drugs already at the advanced stage, such as MK-8998.48,49 We have also provided evidence that patients’ PBMCs respond to drugs that reduce Miro1. This result opens a door to examining personalized drug efficacy and dosing by testing a patient’s own cells before administrating the drug to the patient, thus providing multiple layers of stratification to improve success rates of clinical trials.54 Further studies with independent cohorts are needed to confirm the promise of this test for PD.

Alpha-synuclein aggregation is a pathological hallmark of PD. Emerging evidence has shown that alpha-synuclein has profound functions at the mitochondria or to impact mitochondria, including mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, dynamics, mitophagy, Ca2+, and iron homeostasis.7,33,55–60 Iron accumulation, calcium mishandling, and mitophagy impairment have been individually observed in PD neurons2–10,32–34; however, the relation between these cellular phenotypes in PD has remained obscure. Now we have provided a mechanistic axis connecting them. Fe2+ elicits mitochondrial Ca2+ overload through acting on IMM Ca2+ channels and transporters. The relatively low affinity of MCU to Fe2+ in vitro (Figure 2B) is consistent with its low affinity to other divalent metals such as Mg2+.29 These data suggest that MCU may not be predominantly occupied by these divalent ions under physiological conditions.29 By contrast, under pathological conditions with elevated Fe2+, MCU binds to more Fe2+ and cellular detriment ensues. This finding agrees with prior evidence showing that inhibiting MCU prevents Fe2+-induced cell death36,61 and Parkinsonian neurodegeneration.1,8 Further investigations are needed to dissect how Fe2+ regulates MCUb and NCLX levels. Our results (Figures 2G and 2H) have suggested that Fe2+-triggered Ca2+ efflux delay and the reduction of NCLX and MCUb depend on mitochondrial Ca2+ overload. Thus, it is possible that NCLX and MCUb are targeted by Ca2+-activated mitochondrial proteases. Our data also suggest that Miro1 may link Ca2+ and mitophagy phenotypes in PD. In the same PD neuron models used in this paper, we have previously characterized a delayed mitophagy phenotype downstream of Miro1 retention on damaged mitochondria.32–34 Our paper now shows this Miro1 phenotype is dependent on OMM Ca2+ elevation because of iron accumulation. In addition to mitophagy,32,41,62 Miro may have additional functions in regulating mitochondrial quality control, including the biogenesis of mitochondrial-derived vesicles63 and transcellular mitochondrial transfer.64–68 When Miro senses spatially restricted Ca2+ elevation at the OMM in PD neurons, it may affect multiple Miro-mediated biological processes. More studies are warranted to unravel the precise roles of Miro in PD pathogenesis and how Ca2+ regulates these roles.

Limitations of the study

Flies do not contain an alpha-synuclein homolog, and our results may not account for the physiological roles of human alpha-synuclein. The sample size for the postmortem brain study is relatively small and a larger cohort of PD and PD-related disorders is needed to confirm the prevalence and specificity of the phenotype. Re-evaluation of genetic variants in this pathway is warranted in additional larger cohorts to verify their link to PD. Although MCU oligomerization could be enhanced with a micromolar range of Fe2+ added in the media (Figure 1F), the pathophysiological level of free Fe2+ is difficult to determine in vivo.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the lead contact Xinnan Wang (xinnanw@stanford.edu).

Materials availability

All reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact.

Data and code availability

All original imaging and Western blotting data are available from the lead contact upon request.

Original code and additional method for machine learning has been deposited at Mendeley and is publicly available as of the date of publication. DOI is listed in Method and key resources table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-Miro1 | Sigma | Cat#HPA010687; RRID:AB_1079813 |

| Mouse anti-Miro1 | Sigma | Cat#WH0055288M1; RRID:AB_1843347 |

| Rabbit anti-MCU | Sigma | Cat#HPA016480; RRID:AB_2071893 |

| Rabbit anti-MCU | Proteintech | Cat#26312–1-ap; RRID:AB_2880474 |

| Rabbit anti-Flag | Sigma | Cat#F7425; RRID:AB_439687 |

| Rabbit anti-NCLX | Abcam | Cat#Ab136975 |

| Rabbit anti-MCUb | Abgent | Cat#ap12355b; RRID:AB_10821431 |

| Rabbit anti-GAPDH | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#5174S |

| Rabbit anti-Miro2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#14016S |

| Mouse anti-ATP5β | Abcam | Cat#ab14730, RRID:AB_301438 |

| Mouse anti-Mitofusin2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9482S |

| Mouse anti-MIC60 | Abcam | Cat#ab110329; RRID:AB_10859613 |

| Mouse anti-MIC19 | Origene | Cat#TA803454; RRID:AB_2626833 |

| Rabbit anti-MICU1 | Sigma | Cat#HPA037479 |

| Rabbit anti-MICU2 | Abcam | Cat#ab101465; RRID:AB_10711219 |

| Rabbit anti-FECH | Proteintech | Cat#14466-1-ap; RRID:AB_2231579 |

| Rabbit anti-EMRE | Sigma | Cat#HPA032117; RRID:AB_10601093 |

| Rabbit anti-OPA1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#80471S |

| Rabbit anti-VDAC | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4661S, RRID:AB_10557420 |

| Rabbit anti-β-Actin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4967S |

| HRP-conjugated goat anti-Mouse IgG | Jackson Laboratory | Cat#115-035-166, RRID:AB_2338511 |

| HRP-conjugated goat anti-Rabbit IgG | Jackson Laboratory | Cat#111-035-144, RRID:AB_2307391 |

| DAPI | Sigma | Cat#D9542 |

| DAPI | Thermo Fisher | Cat#D1306 |

| Rabbit anti-TH | EMD Millipore Corporation | Cat#AB152, RRID:AB_390204 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher | Cat#A11008; RRID:AB_143165 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 568 | Invitrogen | Cat#A11004; RRID:AB_2534072 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Alexa Fluor 568 | Abcam | Cat#ab175470; RRID:AB_2783823 |

| Mouse anti-Myc | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc-40; RRID:AB_627268 |

| Mouse anti-T7 | Novagen | Cat#69622 |

| Normal Rabbit IgG | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2729S |

| Biological samples | ||

| Postmortem brain tissues | Stanford University, UCLA, and Banner Sun Health Research Institute | See Table S1 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Antimycin A | Sigma | Cat#A8674 |

| Oligomycin | Sigma | Cat#75351 |

| Thrombin | Sigma | Cat#10602400001 |

| Rhod-2 | Thermo Fisher | Cat#R1244 |

| Calcium Green | Thermo Fisher | Cat#C3011MP |

| RPA | Squarix biotechnology | Cat#ME043.1 |

| MitoTracker Green | Thermo Fisher | Cat#M7514 |

| Mito-FerroGreen | Dojindo Laboratories | Cat#M489 |

| TMRM | Molecular Probes | Cat#T668 |

| CCCP | Sigma | Cat#C2759 |

| 2X Native Sample Buffer | Life Technologies | Cat#LC2673 |

| FCCP | Sigma | Cat#C2920 |

| Hibernate E Low Fluorescence | Transnetyx | Cat#SKU HELF |

| ProLong™ Glass Antifade Mountant with NucBlue™ Stain | Thermo Fisher | Cat#P36983 |

| Fluoromount-G mounting medium | Southern Biotech | Cat#0100-01 |

| Ammonium Iron(II) Sulfate Hexahydrate | Sigma | Cat#203505 |

| Benidipine | Sigma | Cat#B6813 |

| Vitamin C/Ascorbic Acid | Sigma | Cat#A5960 |

| DFP | MedChemExpress | Cat#HY-B0568 |

| Dorsomorphin | Sigma | Cat#P5499 |

| TGFβ Inhibitor SB431542 | Tocris | Cat#1614 |

| GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 | Stemgent | Cat#04-0004 |

| smoothened agonist SAG | CalBioChem | Cat#566661 |

| BDNF | Peprotech | Cat#450-02 |

| FGF8a | R&D Systems | Cat#4745-F8-050 |

| GDNF | Peprotech | Cat#450-10 |

| TGFβ3 | Peprotech | Cat#AF-100-36E |

| dibutyryl-cAMP | Sigma | Cat# D0627 |

| Matrigel | Corning | Cat#354277 |

| Opti-MEM | Gibco | Cat#31985-070 |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Invitrogen | Cat#11668-030 |

| Protein A Sepharose beads | GE Healthcare | Cat#17-0780-01 |

| RU360 | Sigma | Cat#557440 |

| MR3 | MCULE | P-3876569 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| ATP Determination Kit | Sigma | Cat#11699709001 |

| Iron Assay Kit (Colorimetric) | Abcam | Cat#ab83366 |

| MTT Assay Kit | Abcam | Cat#ab211091 |

| RHOT1 ELISA Kit | Biomatik | Cat#EKL54911 |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Scientific | Cat#23227 |

| TUNEL Assay Kit | Invitrogen | Cat#C10618 |

| GFP ELISA Kit | Abcam | Cat#Ab229403 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Code for machine learning | This paper | https://doi.org/10.17632/wtjcvm3cm3.2 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| PD-SNCA-A53T iPSCs | NINDS | ND50050, SNCA (A53T), 51y, Female |

| ND50085, Isogenic control for PD-SNCA-A53T, 51y, Female | ||

| PD-S1 iPSCs | NINDS | ND39896, 77y, Male |

| PD-S2 iPSCs | Applied StemCell | ASE-9028, 82y, Female |

| HC-1 iPSCs | Hsieh et al.32 | 62y, Male |

| HC-2 iPSCs | Stanford Stem Cell Core, Shaltouki et al.33 | 42y, Female |

| Jax-SNCA-A53T iPSCs | Jackson Laboratory | SNCA (A53T), Male |

| Jax-Rev iPSCs | Jackson Laboratory | Isogenic control for Jax-SNCA-A53T |

| Human fibroblasts | NINDS | See STAR Methods |

| PBMCs | Stanford University, Columbia University | See Table S4 |

| HEK293T cells | ATCC | CRL-3216 |

| MCU KO HEK293T cells | Dr. M. F. Tsai | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| TH-GAL4 | Lab stock | N/A |

| UAS-SNCA-A53T | Trinh et al.69 | N/A |

| Actin-GAL4 | Lab stock | N/A |

| UAS-T7-DMiro-WT | Tsai et al.70 | N/A |

| UAS-T7-DMiro-KK | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| GAPDH forward | This paper | 5’ - ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3’ |

| GAPDH reverse | This paper | 5’ - TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGT-3’ |

| Miro1 forward | This paper | 5’ - GGGAGGAACCTCTTCTGGA-3’ |

| Miro1 reverse | This paper | 5’ - ATGAAGAAAGACGTGCGGAT-3’ |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pRK5-GFP-hMiro1-KK | This paper, custom-made by Synbio Technologies | N/A |

| pRK5-GFP-hMiro1-WT | This paper, custom-made by Synbio Technologies | N/A |

| pDsRed2-Mito | Hsieh et al.32 | N/A |

| pUAST-T7-DMiro-KK | This paper | N/A |

| pcDNA-MCU-Flag | Genescript | MCU_OHu20123D_pcDNA3.1+/C-(K)-DYK |

| pcDNA-MCU-3A-Flag | This paper, custom-made by Synbio Technologies | N/A |

| pLX304-miRFP670nano_P2A_GCaMP6f-Miro1-Anchor | This paper | N/A |

| pLX304-miRFP670nano_P2A_ER-GCaMP6f | This paper | N/A |

| pRK5-Myc-hMiro1-WT | Wang et al.43 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism | ver. 5.01, GraphPad | |

| R | package SKAT v2.2.4 | |

| Fuji | V2.14.0 | |

| ImageJ | V1.48 | |

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Human cells and tissues

No human subjects were used in this study. The iPSC work was approved by Stanford Stem Cell Oversight Committee. iPSCs or fibroblasts were purchased under a material transfer agreement (MTA) from NINDS Human Cell and Data Repository or Jackson Laboratory. PBMCs were obtained under an MTA from Columbia University and Michael J. Fox Foundation (MJFF), and from SBC and Stanford Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). Postmortem brain tissues were obtained from Stanford ADRC, Department of Pathology at University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), and Banner Sun Health Research Institute. Columbia University, Stanford University, UCLA, and Banner Sun Health Research Institute Institutional Review Board approved study protocols, which ensured consent from donors and explained the conditions for donating materials for research. Demographic and clinical details of each subject are in Supplementary Tables and key resources table. HEK293T cells were obtained from ATCC. Details of cell culture conditions and authentication are in method details.

Fly model

The following fly stocks were used: Actin-GAL4 (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center–BDSC), TH-GAL4 (BDSC), UAS-SNCAA53T,69 and UAS-T7-DMiro-WT.70 UAS-T7-DMiro-KK were generated by injecting pUAST-T7-DMiro-KK into flies by Bestgene Inc (Chino Hills, CA). All fly stocks and experiments were kept at 25°C with a 12:12 h light:dark cycle and constant humidity (65%) on standard sugar-yeast-agar (SYA) medium (15 g/L agar, 50 g/L sugar, 100 g/L autolyzed yeast, 6 g/L nipagin, and 3 mL/L propionic acid).71 Flies were raised at standard density in 200 mL bottles unless otherwise stated. All fly lines were backcrossed 6 generations into a w1118 background to ensure a homogeneous genetic background. The ages of flies for each experiment were stated in figures. Experiments were carried out on mated females.72

METHOD DETAILS

Constructs

pcDNA3.1-MCU-Flag was purchased from Genescript (MCU_OHu20123D_pcDNA3.1+/C-(K)-DYK). pcDNA3.1-MCU-3A-Flag was generated by Synbio Technologies by making 3 point mutations (74D, 148D, 159H to A) of pcDNA3.1-MCU-Flag. pRK5-GFP-hMiro1-WT or KK was custom-made by Synbio Technologies. pDsRed2-Mito was described in.32 pUAST-T7-DMiro-KK was generated by introducing E234K, E354K to pUAST-T7-DMiro.70 Myc-hMiro1-WT and was described in.43 pLX304-miRFP670nano_P2A_GCaMP6f-Miro1-Anchor or pLX304-miRFP670nano_P2A_ER-GCaMP6f (cytosol) was made by cutting pLX304-miRFP670nano_P2A_EGFP (a gift from Alice Y. Ting) with BsiW1 and Nhe1, amplifying each gene fragment by PCR, and then ligating these with the Gibson assembly method (HiFi master mix, NEB). pcDNA3.1-ER-GCaMP6f (cytosol) was a gift from Chris Richards (Addgene #182548). miRFP670nano was a gift from Vladislav Verkhusha (Addgene #127443). All vectors were confirmed by sequencing.

Cell culture

Human dermal primary fibroblasts isolated from a PD patient (ND39528) and a healthy control (ND36091) were cultured in DMEM (11995-065, Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (900-108, heat-inactivated, Gemini Bio-Products), 1×Anti Anti (15240096, Thermo Fisher), and 1×GlutaMax (35050061, Thermo Fisher) maintained in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator with humidified atmosphere. HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM (11995-065, Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (900-108, heat-inactivated, Gemini Bio-Products), 1% Pen-Strep (15140-122, Gibco), and maintained in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator with humidified atmosphere. Different concentrations of Fe2+ (Ammonium Iron(II) Sulfate Hexahydrate, 203505, Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the media for 20-24 h. The MTT assay (ab211091, Abcam) was used according to the manual. Cells were treated with 10 μM Benidipine (B6813, Sigma-Aldrich), 40 μM CCCP (C2759, Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μM VitC (A5960, Sigma-Aldrich), or 100 μM DFP (HY-B0568, MedChemExpress).

iPSC culture and transfection

All iPSC lines in this study were fully characterized and authenticated by our previous studies,32,33 NINDS Human Cell and Data Repository (https://stemcells.nindsgenetics.org/), Applied StemCell, or Jackson Laboratory. iPSCs were derived to midbrain DA neurons as previously described with minor modifications.32,73–76 Briefly, neurons were generated using an adaptation of the dual-smad inhibition method. Neural induction was started when iPSCs reached 50–85% confluency, with the use of dual smad inhibitors, dorsormorphin (P5499, Sigma-Aldrich) and TGFβ inhibitor SB431542 (1614, Tocris), and the addition of GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 (04–0004, Stemgent) and smoothened agonist SAG (566661, CalBioChem). To get single cells, 12 days after neural induction, half of the medium was replaced with N2 medium with 20 ng mL −1 BDNF (450-02, Peprotech), 200 μM ascorbic acid (A5960, Sigma-Aldrich), 500 nM SAG, and 100 ng mL−1 FGF8a (4745-F8–050, R&D Systems). On day 16–17, neurons were split and transferred onto Matrigel (354277, Corning)-coated or poly-ornithine and laminin-coated glass coverslips in a 24-well plate. On day 19–20, medium was switched to N2 medium supplemented with 20 ng mL−1 BDNF, 200 μM ascorbic acid, 20 ng mL−1 GDNF (450-10, Peprotech), 1 ng mL−1 TGFβ3 (AF-100-36E, Peprotech), and 500 μM dibutyryl-cAMP (D0627, Sigma-Aldrich) for maturation of DA neurons. Neurons were used at day 21–26 after neuronal induction in most of the experiments, when about 80–90% of total cells expressed the neuronal marker TUJ-1, and 14–17% of total cells expressed TH and markers consistent with ventral midbrain neuronal subtypes.33,77 For transfection, on day 19–20 after neural induction, culture medium was replaced with Opti-MEM (Gibco) prior to transfection. For 24-well plates, 0.5–1 μg DNA or 1 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (11668-030, Invitrogen) was diluted in Opti-MEM at room temperature (22°C) to a final volume of 50 μL in two separate tubes, and then contents of the two tubes were gently mixed, incubated for 20 min at room temperature, and subsequently added onto neurons (75,000–120,000 per well). For 6-well plates, 1.5 μg DNA or 6 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (11668-030, Invitrogen) was diluted in Opti-MEM to a final volume of 250 μL in each tube, and mixed, incubated, and applied to neurons (700,000–1,500,000 per well). After 6 h, Opti-MEM containing DNA-Lipofectamine complexes was replaced with regular N2 medium with supplements. For siRNA, NT siRNA (D-001910–10, Horizon Discovery), Cav3.2 siRNA (EQ-006128-00-0002, Horizon Discovery), and delivery media were used according to the manual. After transfection for 2–3 days, neurons were used. Neurons from 6-well plates were lysed in 400 μL lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 0.2 mM PMSF, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, 5 mM EDTA) and used in the Miro1 ELISA kit (EKL54911, Biomatik) following the manual, or in 300 μL Extraction Buffer supplemented with 0.2 mM PMSF and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail and used in the GFP ELISA kit (ab229403, Abcam) following the manual. Neurons were treated with 50–100 μM DFP (HY-B0568, MedChemExpress), 10 μM Benidipine (B6813, Sigma-Aldrich), 500 nM RU360 (557440, Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μM Antimycin A (A8674, Sigma-Aldrich), or 100 μM Antimycin A during live imaging.

Primary drug screens

Overall scheme:

Fibroblasts were plated and cultured for 24 h. Compound libraries were then applied for 10 h. Next, 20 μM FCCP was added for another 14 h. FCCP is a mitochondrial uncoupler that depolarizes the mitochondrial membrane potential.78 Application of mitochondrial uncouplers had been successfully used in high-throughput screens searching for genes and chemicals in the mitophagy pathway.79–81 After fixation, cells were stained with anti-Miro1 and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (Dapi), and imaged under the confocal microscope with the identical setting (Figure 6A). Anti-Miro1 has been validated in ICC for specifically recognizing endogenous Miro1 using human fibroblast-derived neurons with Miro1 RNAi.32 The Miro1 intensity was normalized to Dapi from those images. Using this analysis, we observed significant Miro1 reduction following FCCP treatment in fibroblasts from a healthy control subject but not in a sporadic PD fibroblast line (Figure S6A), consistent with our previous studies using the same cell lines by Western blotting or ELISA.34 We then employed this method to screen 3 chemical libraries (NIH, FDA, and Sigma) using the PD cell line. The NIH Clinical collection library contains 377 unique compounds. We screened those drugs at a defined concentration of 10 μM with 4 biological repeats (independent wells) for each drug. We compared calculated Miro1 levels in PD cells treated with both compound and FCCP to those treated with FCCP but without any compound. We found that 11 out of 377 unique compounds reduced Miro1 protein levels following FCCP treatment on or below 3SD (standard deviation) of control Miro1 values (those from the same PD cell line without compound treatment but with FCCP), in all biological repeats (Figure S4A; Table S2A).82 We next screened the Biomol FDA library with two 5-fold doses (1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 μM). From 175 unique compounds, we identified 3 hits that reduced Miro1 protein levels following FCCP treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S4B; Table S2A). Lastly, we screened the Sigma LOPAC library which contains 1269 unique compounds at a defined concentration of 20 μM. We found that 21 compounds reduced Miro1 protein levels on or below 3SD of those control Miro1 values from the same PD cell line without compound treatment but with FCCP (Figure S4C; Table S2A). We ranked all hits in the order of the degree of Miro1 reduction (Table S2A). It is important to note that from the same screens we also identified compounds that enhanced Miro1 protein levels in PD cells treated with FCCP (Table S2B). Although our purpose was to search for Miro1 reducers in PD models, the same assay could be used to look for Miro1 enhancers in other disease models.

Method details:

Fibroblasts were plated onto clear-bottomed/black-walled 384-well plates (EK-30091, E&K Scientific) at 2,000 cells/well with a Matrix Wellmate dispenser (Thermo Fisher), and plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. Next, chemical library compounds at defined concentrations were added using fully automated liquid handling system (Caliper Life Sciences Staccato system) with a Twister II robot and a Sciclone ALH3000 (Caliper Life Sciences) integrated with a V&P Scientific pin tool, and plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 10 h. Then, 20 μM of FCCP (C2920, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to wells and plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for another 14 h. Cells were fixed with ice-cold 90% methanol (482332, Thermo Fisher) for 20 min at −20°C, then incubated with blocking buffer (10% normal goat serum–50062Z, Thermo Fisher; 0.5% BSA–BP1600, Thermo Fisher; 0.2% Triton X-100–T8787, Thermo Fisher) at room temperature for 15 min, and incubated with anti-Miro1 (HPA010687, Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:100 in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed with 1×PBS (10010-049, Thermo Fisher) using a Plate Washer multivalve (ELx405UV, Bio-Tek), incubated with goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 488 (A11008, Thermo Fisher) at 1:500 in blocking buffer at 25°C for 2 h, then washed again with 1×PBS, and finally 1.0 μg/mL Dapi (D1306, Thermo Fisher) in 1×PBS was added and plates were sealed using PlateLoc (01867.001, Velocity11). All liquids were dispensed using the Multidrop 384 (5840200, Titertek) unless otherwise stated. Fluorescent signals in plates were automatically imaged with ImageXpress Micro (Molecular Devices, IXMicro) and data were analyzed with MetaXpress Analysis (Molecular Devices). One image was taken from one well. Our negative controls without primary anti-Miro1 generated no Miro1 signals. Only cells positive for both Miro1 and Dapi staining were chosen for analysis (>99%; total 400–600 cells per image). The Miro1 fluorescent intensity was normalized to that of Dapi from the same cell and averaged across all cells from the image from one well. Then, the median of the mean Miro1 intensities of all wells from the same plate was calculated and subtracted from the mean Miro1 intensity of each well.

Retesting hits from the primary screens

Overall scheme

To validate the results of the high-content assays, we retested 34 out of the 35 positive Miro1 reducers identified at the Stanford HTBC in our own laboratory using fresh compounds and our confocal microscope. We didn’t test 1 hit (CV-3988) because it was unavailable for purchase at the time of the experiments. We applied each of the 34 compounds at the highest screening concentration to the same sporadic PD line used at the HTBC with at least 4 biological replicates. We also evaluated Miro1 protein levels without FCCP but with compound treatment, which unveiled the drug effect on Miro1 under the basal condition in PD fibroblasts. We imaged all samples with the identical imaging setting, and our negative controls without primary anti-Miro1 yielded almost no signals (background; Table S2C). Four compounds, A-77636 hydrochloride, Ebselen, GBR-12909 dihydrochloride and Fenbufen, appeared toxic (Table S2C). We found that 15 out of the initial 34 hit compounds consistently reduced Miro1 protein following FCCP treatment below 2SD of control Miro1 values (those from the same PD cell line without treatment) (Figure S5; Table S2C).

Method details:

Fibroblasts were plated on coverslips (22–293232, Fisher scientific) into 24-well plates (10861-558, VWR) at 20,000 cells/well and plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. Next, fresh chemical compounds dissolved in DMSO were added at defined concentrations and plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 10 h. Then, FCCP at 20 μM was added to wells and plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for another 14 h. Cells were fixed with ice-cold 90% methanol for 20 min at −20°C, incubated with blocking buffer (10% normal goat serum, 0.5% BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100) at 25°C for 15 min, and immunostained with anti-Miro1 (HPA010687, Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:100 in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed three times with 1×PBS, incubated with goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 488 (A11008, Thermo Fisher) at 1:500 in blocking buffer at 25°C for 2 h, washed again three times with 1×PBS, and finally samples were mounted with ProLong Glass Antifade Mountant with NucBlue (Dapi) Stain (P36983, hard-setting, Thermo Fisher) on glass slides and allowed to cure overnight. Samples were imaged at 25°C with a 20×/N.A.0.60 oil Plan-Apochromat objective on a Leica SPE laser scanning confocal microscope (JH Technologies), with identical imaging parameters among different genotypes. Three images were taken per coverslip. Total 4 biological repeats (coverslips) for each drug. Images were processed with ImageJ (Ver. 1.48, NIH), and the average Miro1 intensity in the cytoplasmic area was measured using the Intensity Ratio Nuclei Cytoplasm Tool (http://dev.mri.cnrs.fr/projects/imagej-macros/wiki/Intensity_Ratio_Nuclei_Cytoplasm_Tool). All compound information for retesting is in Table S2C or in Figure S7.

Pathway analysis

Putative mechanistic pathways were generated using graph search over a network of over 2 million relationships between chemicals, diseases, and genes extracted from the abstracts of journal publications deposited in PubMed.83 Each chemical hit and Miro1 were used as the source and target inputs for a weighted shortest path algorithm where paths were only allowed to traverse chemical-gene and gene-gene relationships. Graph search over the biomedical graph was performed using Neo4J. A subnetwork associated with each shortest path was generated from its supporting documents and analyzed using a knowledge graph browser (docs2graph) to curate the set of supporting documents.

Immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy

Adult fly brains were dissected in PBST (0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) and incubated with fixative solution (4% formaldehyde in PBST) for 15 min at room temperature. Fixed samples were incubated in blocking solution (10% BSA in PBST) for an hour, and then immunostained with rabbit anti-TH (AB-152, EMD Millipore) at 1:200 in blocking solution for 36 h at 4°C on a rotator. After wash, donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 (ab175470, Abcam) at 1:1000 was applied in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature in dark. The DA neuron number was counted throughout the z stack images of each brain. Representative images were summed stack images. Human neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for 15 min at room temperature, permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min, then washed twice in PBS (5 min each) and rinsed in deionized water. Alexa Fluor 594 picolyl azide based TUNEL assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction (C10618, Invitrogen). Coverslips were incubated with TdT reaction buffer at 37°C for 10 min, followed by TdT reaction mixture at 37°C for 60 min in a humidified chamber. Coverslips were then rinsed with deionized water, washed with 3% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, followed by incubation with Click-iT plus TUNEL reaction cocktail at 37°C for 30 min, and then washed with 3% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. For nuclear counterstain, 4′, 6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (Dapi; D9542, Sigma-Aldrich) at 0.5 μg/mL was applied at room temperature for 10 min in the dark. The coverslips were washed with PBS twice, and then mounted on slides with Fluoromount-G mounting medium (SouthernBiotech). For some experiments, Dapi was stained with ProLong Glass Antifade Mountant with NucBlue Stain (P36983, hard-setting, Thermo Fisher). Or iPSC-derived neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed twice in PBS (5 min each), and then blocked in PBS with 5% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 60 min. Neurons were then immunostained with rabbit anti-TH (AB-152, EMD Millipore) at 1:500, rabbit anti-Flag (F7425, Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:500, or mouse anti-Myc at 1:1,000 (sc-40, Santa Cruz) in antibody buffer (PBS with 1% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100) at 4°C overnight, followed by Alexa Fluor 488 fluorochrome conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (A11008, Invitrogen) or Alexa Fluor 568 fluorochrome conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (A11004, Invitrogen) at 1:500 in antibody buffer at room temperature for 1 h. Coverslips were washed with PBS twice, and then mounted on slides with Fluoromount-G mounting medium. Samples were imaged at room temperature with a 20×/N.A.0.60 or 63×/N.A.1.30 oil Plan-Apochromat objective on a Leica SPE laser scanning confocal microscope, with identical imaging parameters among different genotypes in a blinded fashion. Images were processed with ImageJ (Ver. 1.48, NIH) using only linear adjustments of contrast and color.

Live cell imaging

RPA at 5 μM (ME043.1, Squarix biotechnology), Mito-FerroGreen at 5 μM (M489, Dojindo Laboratories), MitoTracker Green at 75–100 nM (M7514, Thermo Fisher), or TMRM at 25 nM (T668, Molecular Probes) was applied to cells on coverslips in culture media or Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) at 37°C for 30 min, then coverslips were washed with HBSS and each was placed in a 35-mm Petri dish containing Hibernate E low-fluorescence medium (HELF, BrainBits/Transnetyx), and cells were imaged immediately on a heated stage at 37°C with a 63/N.A.0.9 water-immersion objective. For calcium imaging, Rhod-2 (R1244, Thermo Fisher) and Calcium Green (C3011MP, Thermo Fisher) at 5 μM were applied to cells on coverslips and incubated at 37°C for 30 min and imaged with the same set-up as above. Thrombin (10602400001, Sigma-Aldrich) was applied at 100 mUnits/ml to the dish during imaging. 500 μM Fe2+ was applied the day before. Time-lapse movies were obtained continually with a 2 s interval for 8–10 min. For Mito-dsRed and GFP-Miro1 imaging, live neurons were imaged as above and time-lapse movies were obtained continually with a 1 s interval before and after 100 μM Antimycin (A8674, Sigma-Aldrich) addition.

Fly behavioral analysis

DFP (HY-B0568, MedChemExpress) was dissolved in water at 50 mM and added to SYA fly food at a final concentration of 163 μM. Benidipine (B6813, Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM and added to SYA fly food at a final concentration of 2.5 μM. The same volume of solvent was added to control food. Drug treatment was started on newly-eclosed mated females (day 1), except for DFP on locomotion which was started from embryogenesis. Food was refreshed every 2 days. The average Performance Index (PI) (negative geotaxis) was evaluated as previously described.72,84,85 Briefly, adult flies were gently tapped to the base of a modified 25 mL climbing tube and their climbing progress was recorded after 45 s. Two to four populations of flies were assessed, and for each population, flies were examined 3 times per experiment. The recorded values were used to calculate the average PI.

Western blotting and IP