Abstract

Chaperones are a large family of proteins crucial for maintaining cellular protein homeostasis. One such chaperone is the 70 kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70), which plays a crucial role in protein (re)folding, stability, functionality, and translocation. While the key events in the Hsp70 chaperone cycle are well established, a relatively small number of distinct substrates were repetitively investigated. This is despite Hsp70 engaging with a plethora of cellular proteins of various structural properties and folding pathways. Here we analyzed novel Hsp70 substrates, based on tandem repeats of NanoLuc (Nluc), a small and highly bioluminescent protein with unique structural characteristics. In previous mechanical unfolding and refolding studies, we have identified interesting misfolding propensities of these Nluc‐based tandem repeats. In this study, we further investigate these properties through in vitro bulk experiments. Similar to monomeric Nluc, engineered Nluc dyads and triads proved to be highly bioluminescent. Using the bioluminescence signal as the proxy for their structural integrity, we determined that heat‐denatured Nluc dyads and triads can be efficiently refolded by the E. coli Hsp70 chaperone system, which comprises DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE. In contrast to previous studies with other substrates, we observed that Nluc repeats can be efficiently refolded by DnaK and DnaJ, even in the absence of GrpE co‐chaperone. Taken together, our study offers a new powerful substrate for chaperone research and raises intriguing questions about the Hsp70 mechanisms, particularly in the context of structurally diverse proteins.

Keywords: bioluminescence, chaperone mechanism, DnaK, Hsp70, NanoLuc, protein refolding, tandem repeats

1. INTRODUCTION

In the quest of understanding the mechanisms behind protein homeostasis, including polypeptides folding, misfolding, and refolding, the ubiquitous chaperones and their multiplicity of function have been the center of attention (Bukau & Horwich, 1998; Georgopoulos & Welch, 1993; Hartl et al., 2011; Mathew & Morimoto, 1998; Richter et al., 2010; Rosenzweig et al., 2019; Welch & Brown, 1996; Wickner et al., 2021). Chaperones are promiscuous, interacting with a large number of substrate proteins, also referred to as client proteins, and employ various mechanisms to assist the folding of nascent chains, to refold misfolded and aggregated proteins, and to aid protein degradation of proteins damaged beyond repair (Arhar et al., 2021; Clerico et al., 2019; Mayer, 2018; Rosenzweig et al., 2019; Zolkiewski et al., 2012). The chaperone systems are however challenging to study given their highly dynamic nature and the complexity of their assemblies. Chaperone proteins usually display allosteric conformational changes, with many intermediate states when interacting with substrates, co‐chaperones, and nucleotides, which are challenging to capture. One of the fundamental and most studied chaperone systems is the E. coli heat shock protein Hsp70 (DnaK), along with its co‐chaperone DnaJ and GrpE (Mayer & Gierasch, 2019; Rosenzweig et al., 2019; Zylicz & Wawrzynow, 2001). Biochemical methods (Packschies et al., 1997; Rohland et al., 2022; Schröder et al., 1993; Szabo et al., 2006), protein structure determination (X‐ray crystallography, NMR, Cryo‐EM) (Bertelsen et al., 2009; Clerico et al., 2021; Harrison et al., 1997; Jiang et al., 2019; Kityk et al., 2018; Zhuravleva et al., 2012; Zhuravleva & Gierasch, 2015), single molecule studies (single molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS)) (Dahiya et al., 2022; Mashaghi et al., 2016; Moessmer et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2022), and single‐pair fluorescence resonance energy transfer (spFRET) (Imamoglu et al., 2020) identified the significance of every protein in this system. The consensus is that DnaJ, a Hsp40, initially binds to the substrate proteins that are partially or fully unfolded (Perales‐Calvo et al., 2010). Then, the DnaJ‐bound substrate is transferred to the ATP‐bound DnaK (Imamoglu et al., 2020; Rohland et al., 2022; Russell et al., 1999). Both DnaJ and the substrate trigger ATP hydrolysis, which is followed by the disassociation of DnaJ from the complex (Kityk et al., 2018; Russell et al., 1999). Many studies have shown a variety of conformational changes occurring on DnaK, before and after ATP hydrolysis, signifying a highly complex system (Imamoglu et al., 2020; Rohland et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021). GrpE, a nucleotide exchanger for DnaK, then binds to the DnaK•ADP•substrate complex, releasing the ADP, causing a reverse conformational change to DnaK and release of the substrate. This allows new ATP to bind to DnaK, resulting in the initiation of a new cycle, and the overall process to continue for many rounds until the substrate proteins are fully folded (Banecki & Zylicz, 1996). Additionally, many studies have shown that DnaJ and DnaK have a preference for short sequences containing hydrophobic residues (Rüdiger et al., 1997, 2001) and prediction algorithms have been generated (Van Durme et al., 2009) that can identify potential DnaK‐binding motifs in substrate proteins.

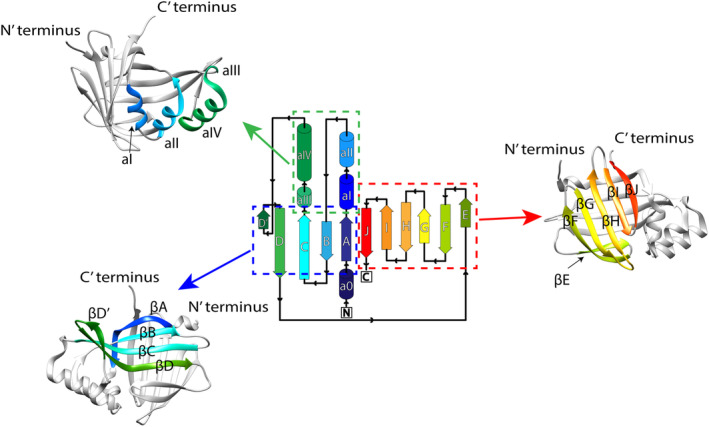

While DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE are believed to assist up to 700 proteins in the E. coli cytosol (Calloni et al., 2012; Kerner et al., 2005), so far only a small number of substrates, such as firefly luciferase (Fluc) (Imamoglu et al., 2020; Schröder et al., 1993), proPhoA (Clerico et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2019; Rohland et al., 2022), σ32 (Liberek et al., 1992), maltose binding protein (MBP) (Jiang et al., 2019), ubiquitin (Perales‐Calvo et al., 2018), Protein L (Chaudhuri et al., 2022), titin I91 domain (Nunes et al., 2015; Perales‐Calvo et al., 2018), malate dehydrogenase (MDH) (Srinivasan et al., 2012), and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (Moessmer et al., 2022) have been directly used for studying the mechanism of this chaperone system. All structured proteins are characterized by their unique energy landscape, with larger proteins having multiple folding intermediates with varying kinetics of transition among the various states. Addition of chaperones affects the energy landscape of these proteins modulating the protein's energy landscape (Hartl et al., 2011). We believe that testing a larger and more diverse library of distinct substrates would further strengthen the current model of the DnaK mechanism. This is due to the fact that a diverse library of substrates will represent various protein structural characteristics, misfolding pathways, and possibly various degrees of assistance required during refolding. On the other hand, such studies may also allow capturing DnaK mechanistic nuances and potentially even deviations from the canonical model. Toward this end, we report here the development and testing of a new DnaK substrate, based on tandem repeats of the small highly bioluminescent protein NanoLuc (Nluc) (Hall et al., 2012). Nluc is a bioluminescent protein engineered by Promega, based on a small, 19 kDa, subunit of the deep sea shrimp Oplophorus gracilirostris (OLuc) luciferase that was subjected to several rounds of mutations (Hall et al., 2012). The final result of Nluc's sequence is unique among known proteins (Figure 1), and it displays only distant similarities with a family of intracellular lipid‐binding proteins (iLBPs) (Hall et al., 2012). Nluc is known to produce a 150 times brighter BL signal than Fluc and is thermally and chemically robust as a monomer (Hall et al., 2012). Also, Nluc is known to oxidize furimazine by a catalytic reaction, which is ATP‐independent, producing light at the blue wavelength (England et al., 2016; Hall et al., 2012). Since Hsp70 mediated chaperone reactions are ATP‐dependent, this ATP independence of Nluc bioluminescence (BL) may be an advantage over other bioluminescent proteins such as Fluc, one of the most common substrates that itself requires ATP to produce BL signal.

FIGURE 1.

Nluc protein's topology (source: PDBsum for entry 5IBO). The structure of Nluc is deposited in the PDB website with code 5IBO. We used the USCF Chimera program to visualize the structure using the rainbow depiction. Parts of the protein structure were grouped and shown in the obtained X‐ray structure using the same colors for clarity. Various β‐sheets and α‐helices are named as in the protein's topology.

We recently carried out extensive single‐molecule force spectroscopy characterization of Nluc nanomechanics and observed that monomeric Nluc flanked by I91 domains of titin (I912‐Nluc‐I914) and multiple Nluc separated by I91 titin domains (I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91) refold quite robustly after mechanical unfolding (Apostolidou et al., 2022). However, triads of Nluc flanked by I91 titin domains (I91‐I91‐Nluc‐Nluc‐Nluc‐I91‐I91) surprisingly displayed a high propensity of misfolding in mechanical unfolding‐refolding cycles (Ding et al., 2020). This observation prompted us to consider whether heat‐shocked Nluc dyads and triads could be good substrates for the Hsp70 system, where we could exploit their strong BL to directly follow their thermal denaturation and refolding.

Indeed, we were able to determine from BL assays that poly‐Nluc constructs, dyads and triads of Nluc, showed a decreased thermal stability, in contrast to monomeric Nluc, and would, in addition, not refold on their own. Most importantly, we were able to demonstrate that poly‐Nluc constructs are strong chaperone substrates that are efficiently refolded by the DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE system. Their refolding reaction showed strong ATP‐hydrolysis dependence typical of other substrates, but interestingly displayed very weak GrpE dependence. This surprisingly weak GrpE dependence is different from the canonical pathway of other substrates studied so far (Mayer & Gierasch, 2019). We also performed both coarse‐grained and all‐atoms simulations of Nluc and poly‐Nluc constructs, which provided structural information on the degree of misfolding and their putative mechanism, after thermal denaturation. Overall, our study shows that poly‐Nluc constructs may be useful new substrates for studying chaperone reactions in vitro and open interesting questions on the relationship between protein misfolding pathways and chaperone reaction mechanisms.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

2.1. Dyad Nluc and triad Nluc have lower thermal stability as compared to monomeric Nluc

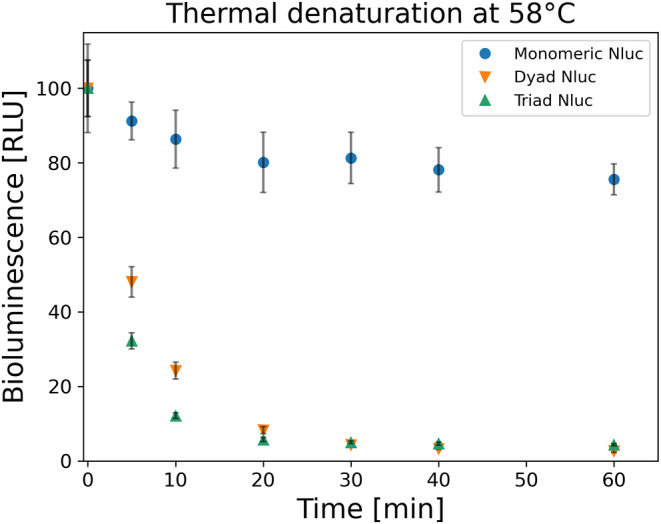

For the thermal denaturation studies of Nluc, we used three constructs each consisting of various repeats of Nluc: one Nluc (monomeric Nluc), two NanoLucs connected by four residues linker (dyad Nluc), and three NanoLucs connected by four residues linker (triad Nluc). It has been reported by Promega Company that Nluc has a melting temperature of 58°C (Kopish et al., 2012). Therefore, we proceeded by denaturing all constructs at 58°C for 1 h collecting various time points in between to follow the time evolution of denaturation. As seen in Figure 2, in our hands, monomeric Nluc demonstrated good thermal stability at 58°C, with only 20% of the initial BL signal lost after 1 h. However, for dyad Nluc and triad Nluc, the BL signal dropped drastically even after 10 min at 58°C, with approximately 25% and 10% activity. The rate of BL signal decay was 0.153 ± 0.002 min−1 (mean lifetime approximately 5 min) for dyad Nluc and 0.250 ± 0.003 min−1 (mean lifetime approximately 3 min) for triad Nluc.

FIGURE 2.

Thermal denaturation of 100 nM monomeric, dyad and triad Nluc constructs at 58°C (n = 3). All proteins were diluted down to 1 nM and the BL signal was measured at various time points. Collected values were normalized by the initial BL signal at time zero before the thermal denaturation of the proteins (n = 3). After 1 h, the BL signal for monomeric Nluc (blue circle) drops to 80% active protein, while for both dyad (orange down facing triangle) and triad (green up facing triangle) Nluc constructs less than 4% of active proteins.

2.2. Dyad Nluc and triad Nluc are substrates for chaperone‐assisted refolding

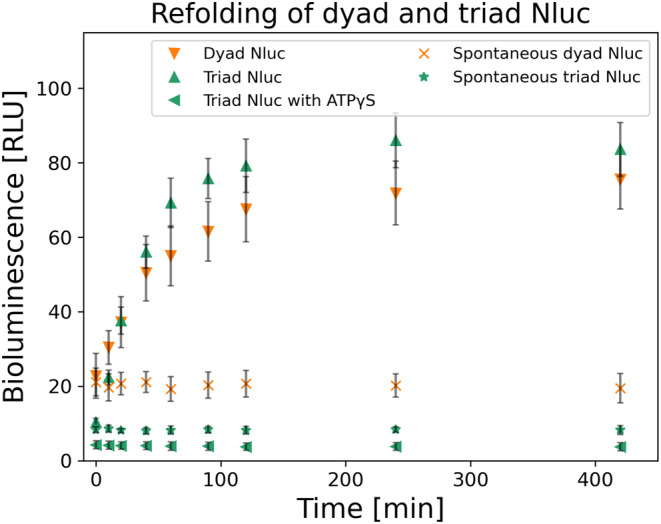

Our thermal denaturation experiments demonstrated limited thermal stability for both the dyad and triad Nluc constructs as compared to the monomeric Nluc, when using bioluminescence activity as a proxy for structural integrity. Therefore, we proceeded to examine if these two constructs can spontaneously refold. As shown in Figure 3, both constructs at 10 nM had no spontaneous refolding even after 7 h. However, when we examined the refolding of the dyad and triad Nluc constructs after the addition of the E. coli chaperone refolding system comprising of DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE chaperones, we saw a significant BL signal recovery (Figure 3). Following the chaperone concentrations previously used in literature 3 μΜ DnaK, 1 μΜ DnaJ, and 1.5 μΜ GrpE (Imamoglu et al., 2020), we refolded the two constructs after denaturing them for 10 min at 58°C. The 7 h experiment shows recovery for dyad Nluc up to more than 75% total BL signal (at time zero BL signal was about 20%). For triad Nluc the final BL signal after 7 h was about 85% (at time zero BL signal was about 10%). The striking difference between the spontaneous and chaperone‐assisted refolding results clearly shows that chaperones enable Nluc's refolding.

FIGURE 3.

Chaperone assisted refolding of 10 nM dyad (orange down facing triangle) and triad (green up facing triangle) Nluc constructs (n = 3). Both constructs were denatured for 10 min at 58°C at 100 nM, followed by a short 30 s room temperature cool down, before their 10x dilution to 10 nM in Buffer C including 3 μM DnaK, 1 μM DnaJ, 1.5 μM GrpE. BL signal recovery was collected for various time points for up to 7 h (n = 3). Additionally, for triad Nluc we performed the same experiment switching ATP with ATPγS in Buffer C (green left facing triangle) and collected BL signal for various time points up to 7 h (n = 3). Lastly, spontaneous refolding was examined, following the same denaturation and short cooling times as mentioned above, by diluting the proteins to 10 nM in Buffer C in the absence of all three chaperones. Various time points of the spontaneous BL signal recovery were collected (n = 3). For dyad Nluc the starting BL signal is about 25% of active protein and after 7 h it rises to about 75%. Similarly, for the triad Nluc the initial BL signal is about 10% of active protein and after 7 h it rises to about 85%. However, the refolding reaction with ATPγS showed no refolding with the BL signal remaining constant after 7 h at about 5%. Both proteins show no spontaneous recovery with their values after 7 h of experiments to about 25% for dyad (orange x) and 10% for triad Nluc (green star). All BL values were normalized to the initial BL for 100% of active protein before thermally denaturing it.

The kinetics of the reactions for both constructs were fitted using equation which resulted in half times of 19 min for dyad Nluc and 24 min for triad Nluc.

To further support the fact that chaperones assist in the refolding of the two constructs and eliminate crowding effects as potential reasons for refolding, we performed additional experiments. Those included refolding of the triad Nluc in (a) 7 μM BSA, (b) 3 μM DnaK with 4 μM BSA, and (c) 1 μM DnaJ (Figure S1). In all cases, there was no observed refolding even after 7 h and the results resembled those of spontaneous refolding.

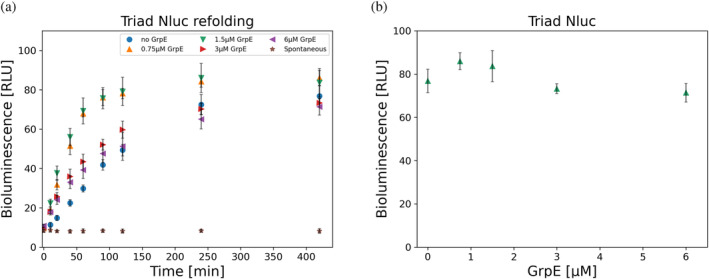

2.3. Triad Nluc refolds even in the absence of GrpE

It has been shown numerous times that the presence of all three chaperones, DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE, is crucial for protein refolding (Schröder et al., 1993; Szabo et al., 2006). We already tested and confirmed that the triad Nluc cannot refold in the presence of only DnaJ or only DnaK. Therefore, we examined if and how GrpE is contributing to triad Nluc's refolding. Interestingly, we were able to refold triad Nluc up to approximately 70% after 7 h in the absence of GrpE (initial BL signal was about 10%). We had similar observations for dyad Nluc, which was also able to refold in the absence of GrpE (results not shown). We further proceeded to test the possible effect of GrpE at various concentrations, 0–6 μM, and we found that GrpE has some positive impact on triad Nluc refolding, in a narrow concentration range, with an optimal range of GrpE around 0.75–1.5 μM. Beyond this optimal concentration range, the refolding recovery would decrease at higher GrpE concentrations. Time points for the 7 h experiments for 3 μM DnaK, 1 μM DnaJ, and various GrpE concentrations are shown in Figure 4a. In Figure 4b we have compiled together the 7 h time points of triad Nluc refolding for various GrpE concentrations to further demonstrate the refolding trend at 7 h.

FIGURE 4.

Bioluminescence (BL) refolding of triad Nluc. (a) BL signal from refolding of 10 nM triad Nluc in Buffer C in the presence of 3 μM DnaK, 1 μM DnaJ, and various GrpE concentrations for 7 h (n = 3). The protein was initially heat shocked at 58°C for 10 min at 100 nM and diluted 10x in refolding Buffer C containing the chaperones. Refolding kinetics were observed for 7 h in total in every case. Spontaneous refolding of triad Nluc in the absence of all three chaperones is also presented in which triad Nluc was diluted 10x in Buffer C in the absence of chaperones showing no recovery of the protein. Data with 1.5 μM GrpE and spontaneous refolding are also presented in Figure 3. (b) Compilation of the BL signal results at 7 h timepoints for triad Nluc in the presence of 3 μM DnaK, 1 μM DnaJ for various GrpE concentrations (n = 3). We observe an optimal concentration for these conditions to be 0.75–1.5 μM of GrpE.

To make sure that GrpE, as well as DnaK and DnaJ, are fully functional in our assays, we assessed all three chaperones by performing standard refolding reactions of Fluc in the presence and absence of GrpE (Figure S2). Contrary to our results of triad Nluc, Fluc was unable to successfully refold in the absence of GrpE, with minor spontaneous refolding present after 2 h. Despite Fluc's BL signal starting at about 10% after heat shock, with the addition of GrpE, it reached about 85% of refolding after only 2 h (Figure S2a). On the other hand, the spontaneous BL signal changed from about 5% to about 10% for the same period. Later addition of GrpE (1 h 30 min) to the spontaneous refolding of Fluc resulted in a similarly high recovery of Fluc's BL signal up to about 85%, while spontaneous refolding remained at about 10% even after 3 h (Figure S2b). Our refolding results with Fluc follow those previously done by other groups (Imamoglu et al., 2020; Schröder et al., 1993).

The observation that GrpE is not as crucial in refolding the dyad and triad Nluc constructs, contrary to Fluc, is significant as it marks a deviation from the canonical DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE mechanism suggested up till now. Previous studies have shown that GrpE is crucial in aiding the refolding kinetics of the substrate proteins (Schröder et al., 1993). Interactions of DnaK and GrpE in the presence and absence of substrates have previously been shown (Brehmer et al., 2004; Schönfeld et al., 1995). Furthermore, acceleration of the kinetics of the reactions by GrpE has been observed in the absence of a substrate (maximal 5000‐fold) (Packschies et al., 1997), and the presence of peptides (200‐fold) (Mally & Witt, 2001). While in our studies GrpE is not essential for Nluc refolding, we do find refolding efficiency to be slightly increased at an optimal ratio of GrpE:DnaJ of 1.5 which is similar to other studies (Imamoglu et al., 2020; Packschies et al., 1997). Our results of refolding Fluc in the presence and absence of GrpE for the same concentrations of chaperones agree with past results (Imamoglu et al., 2020; Schröder et al., 1993). Thus, our results for Fluc exclude the possibility of a GrpE deficiency as the reason for the deviation in the GrpE dependency of the refolding mechanism between the Nluc constructs and Fluc.

To understand why GrpE was not essential in our triad Nluc refolding experiments, we determined the ATPase activity of DnaK during Nluc refolding reactions (Figure S9). Our results showed that the ATP hydrolysis rate associated with the refolding of triad Nluc in the presence of 3 μM DnaK, 1 μM DnaJ, and 1.5 μM GrpE is 2.30 μM min−1. In contrast, the ATPase rate in the absence of GrpE is 1.68 μM min−1 reduced only by 27%. This indicates that GrpE is non‐essential for the ATPase activity of DnaK under our experimental conditions. One interesting observation is that, although GrpE is not essential, it does contribute to increasing the refolding rate of Nluc in the initial hours, consistent with some contribution to the increased rate of ATP hydrolysis. The BL signal of triad Nluc, when 1.5 μM GrpE is present, reaches 70% recovery in 1 h. In contrast, it takes about 4 h to reach the same levels of triad Nluc recovery in the absence of GrpE (Figure 4a). Therefore, the increased ATP hydrolysis in the presence of GrpE contributes to the rate of refolding of the triad Nluc, although it is of a non‐essential nature.

2.4. ATP hydrolysis catalyzed by DnaK is important for triad Nluc refolding

Allosteric conformation changes of DnaK have been shown to contribute to substrate protein refolding (Hendrickson, 2020; Wang et al., 2021). A previous study showed that the substitution of ATP with ATPγS, an ATP analog known as an inhibitor of the ATPase activity of Hsp70s, results in an inability of DnaK to have a conformational change impeding its ability to refold proteins (Theyssen et al., 1996). However, because of our unexpected result of GrpE on triad Nluc's refolding by DnaK, we decided to also examine if ATP hydrolysis is necessary for triad Nluc's refolding. We present here that ATP hydrolysis is fundamental for triad Nluc refolding (Figure 3). Refolding reaction with 3 μM DnaK, 1 μM DnaJ, and 1.5 μM GrpE in the presence of 10 mM Mg(OAC)2, and 5 mM ATPγS showed no recovery for triad Nluc with its bioluminescence remaining at ~5% of total activity even after 7 h.

Therefore, despite showing that GrpE is not essential for the refolding of triad Nluc, the substitution of ATP with its non‐hydrolyzable analog ATPγS resulted in no recovery of the triad Nluc activity. This result suggests that the allosteric communication within DnaK, which is in conjunction with the ATP binding and hydrolysis, is important for triad Nluc refolding and without it, the protein most likely remains trapped in a non‐native intermediate state (Rohland et al., 2022). NMR studies have previously shown how ATPγS inhibits key conformational changes in DnaK, which can eventually affect its interaction with the substrate (Zhuravleva et al., 2012). Therefore, without DnaK tightly binding to triad Nluc, the latter is not assisted in its recovery back to its native state, exposing it to potential inter‐ and intra‐domain misfolding, and possibly exposing it to interactions with other proteins in solution (intermolecular misfolding). Additional studies with mutated DnaK, which is unable to hydrolyze ATP, are warranted, since these experiments would further illustrate how the DnaK allosteric changes are contributing to the poly‐Nluc's refolding.

2.5. Chaperone assisted refolding of Nluc tandem repeats when separated by I91 titin domains

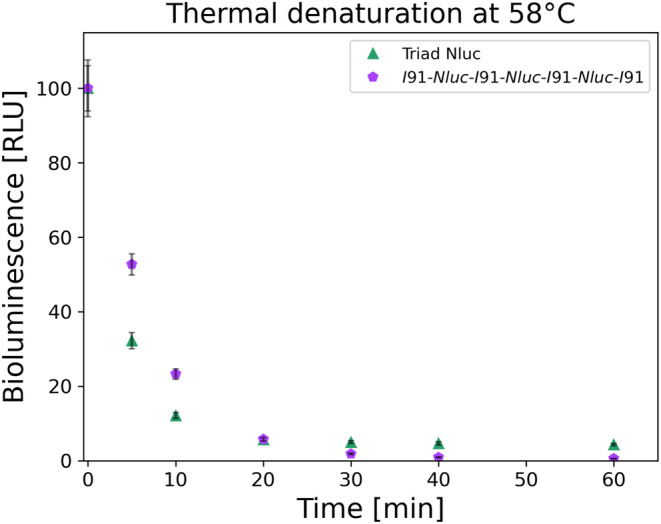

As previously mentioned, the three Nluc proteins in the triad Nluc construct are connected by four residues as linkers. The proximity of the Nluc repeats can potentially contribute to inter‐repeat misfolding of the Nluc polyproteins within the same construct. To do this, we exploited our earlier construct involving tandem repeats of Nluc and I91 domain of titin (Apostolidou et al., 2022), the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91, in which the three Nluc repeats are separated by the titin I91 domain () (Botello et al., 2009; Politou et al., 1995; Tskhovrebova & Trinick, 2004). We began by examining the thermal stability of the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct. Our thermal denaturation experiments showed a slightly higher thermal stability for the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct as compared to triad Nluc at short denaturation times (less than 20 min). However, at 20 min of initial thermal denaturation, the BL signal drops for both triad Nluc and I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 constructs to a similar level and at longer times the BL signal is slightly higher for the triad Nluc as compared to the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct (Figure 5). These results show overall similar thermal behavior between the two constructs. The small difference in denaturation level between the two constructs (10% for triad Nluc and 23% for I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91) for same concentrations and conditions suggests that the I91 titin domains assist in a small degree in reducing the thermal denaturation of Nluc proteins in the construct, by providing additional separation. The rate of BL signal decay for the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct was 0.138 ± 0.006 min−1 (mean lifetime approximately 5 min), while triad Nluc had a mean lifetime of about 3 min.

FIGURE 5.

Thermal decay of 100 nM triad Nluc (green up facing triangle) and I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 (purple pentagon) constructs at 58°C after 1 h (n = 3). Both constructs show the decay of the BL signal with the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 initially showing less denaturation due to the increased temperature. After 20 min of denaturation, both constructs appear to have the same BL values below 5% of active protein. The results for the triad Nluc are also shown in Figure 2.

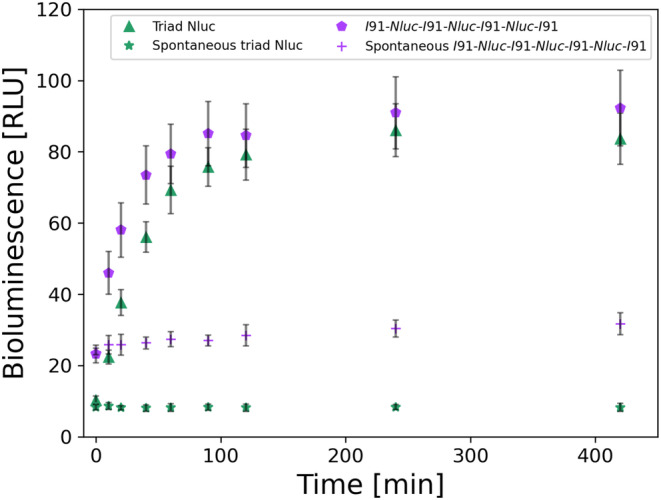

Additionally, we tested how chaperones assist in the refolding of the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct in comparison to the triad Nluc (Figure 6). We found that the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct was also able to recover in the presence of DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE with up to 92% active protein after 7 h of experiments (initial value was 23% active protein) while triad Nluc reaches 85%. Additionally, we observed a negligible recovery from 24% to 31% for the spontaneous refolding. The kinetics of these reactions were fitted using equation, which resulted in half times of 12 min for Nluc of the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct. Thus, both protein constructs show strong refolding behavior, which in the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct appears to be enhanced by the I91 titin domains.

FIGURE 6.

Chaperone‐assisted refolding of 10 nM triad Nluc (green) and 10 nM I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 (purple) constructs (n = 3). Both constructs were denatured for 10 min at 58°C at 100 nM, followed by a short 30 s room temperature cool down, before their 10x dilution in the Buffer C including 3 μM DnaK, 1 μM DnaJ, 1.5 μM GrpE. BL signal recovery was collected for various time points for up to 7 h (n = 3). Additionally, we examined the spontaneous refolding after the same denaturation and short cooling times as mentioned above, by diluting the proteins in Buffer C in the absence of all three chaperones, and time points of the BL signal recovery were collected (n = 3). For the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct (purple pentagon) the BL signal is initially at 23% active protein and after 7 h reaches about 95%. For triad Nluc (green up facing triangle) the initial BL signal is about 10% active protein and after 7 h it rises to about 85%. I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 (purple cross) had very minimal spontaneous recovery with 35% active protein from the initial 23%. All BL values were normalized to the initial BL for 100% of active protein before thermally denaturing it. Data of the triad Nluc (green) are also presented in Figure 3.

Our thermal and mechanical unfolding and refolding studies of I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 and triad Nluc (or I91‐I91‐Nluc‐Nluc‐Nluc‐I91‐I91) are very intriguing. Our previous mechanical unfolding/refolding studies of I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 and triad Nluc flanked by I91s: I91‐I91‐Nluc‐Nluc‐Nluc‐I91‐I91 polyprotein construct (Apostolidou et al., 2022; Ding et al., 2020) showed that the latter misfolded with higher probability. These results are not in complete agreement with our thermal denaturation results of I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 and triad Nluc. This can be the consequence of the denaturation method used further emphasizing the differences between thermal and mechanical denaturation pathways with regards to the structural changes the protein undergoes. Because titin I91 domains have a higher denaturation temperature than Nluc (), we consider the titin I91 domains to be mostly folded during our thermal denaturation experiments. However, given the two‐times smaller size of titin I91 domains (~10 kDa) when compared to Nluc (~19 kDa), it is possible that the Nluc domains interact with each other in the construct at elevated temperatures leading to their permanent misfolding and therefore require chaperones for refolding. Of note is the observation that the rate of spontaneous refolding of this construct is somewhat higher as compared to triad Nluc (Figure 6), suggesting some small but positive effect of Nluc domains separation on structure recovery after thermal denaturation.

2.6. Coarse‐grained MD simulations

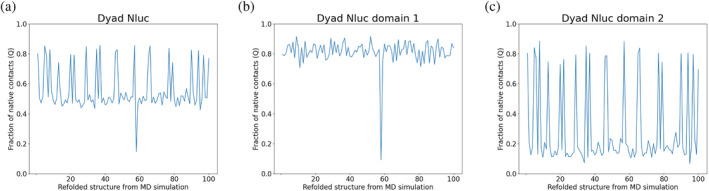

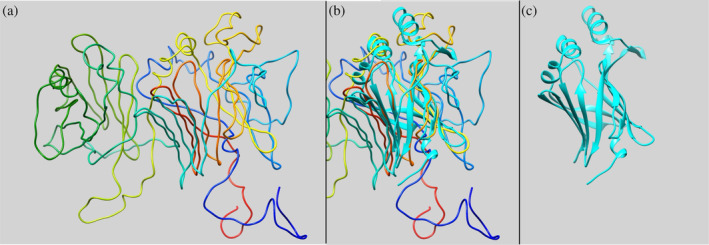

In order to elucidate potential intra‐repeat (within one Nluc repeat) and inter‐repeat (among many Nluc repeats) misfolding in one poly‐Nluc construct as a result of thermal denaturation, we performed coarse‐grained (CG) MD simulations for a total of 500 ns per simulation using 150 temperature unit. These are essential research tools for capturing possible misfolding structures in thermally‐denatured Nluc constructs and explain the different behavior of monomeric, dyad, and triad Nluc, in parallel to our experimental data. As expected from the CG methodology that favors native contacts, the coarse‐grained simulations of refolding for monomeric Nluc (n = 100) resulted in completely refolded structures (Figure S3). For dyad Nluc however, the fraction of native contacts is near 0.5 for 78 MD simulations, which means there is around 78% possibility for one domain to misfold. In addition, 21 simulations generated a well‐refolded structure, and 1 simulation generated a fully misfolded structure (Figure 7a). In more detail, almost all simulations have well‐refolded domain #1 (residue 23–193), except for 1 simulation, which corresponds to the fully misfolded structure (Figure 7b), and the domain #2 (residue 198–368) is usually misfolded (Figure 7c).

FIGURE 7.

Coarse‐grained simulations of dyad Nluc (n = 100). In all figures, we compare native contacts of the initial and final structure per simulation. In (a) we present the fraction of native contacts Q for both domains 1 and in (b) we present domain 1 (residue 23–193) and in (c) we present domain 2 (residue 198–368). As can be seen, the fraction of native contacts is 0.5 (n = 78) indicating a 78% possibility that one domain will misfold. The rest of the 21 simulations showed a well‐refolded structure for the dyad Nluc, and 1 simulation showed a fully misfolded structure. The fraction of native contacts in (b) and (c) for domain 1 and domain 2, respectively, show how domain 1 is folded apart from one case, while domain 2 is usually misfolded.

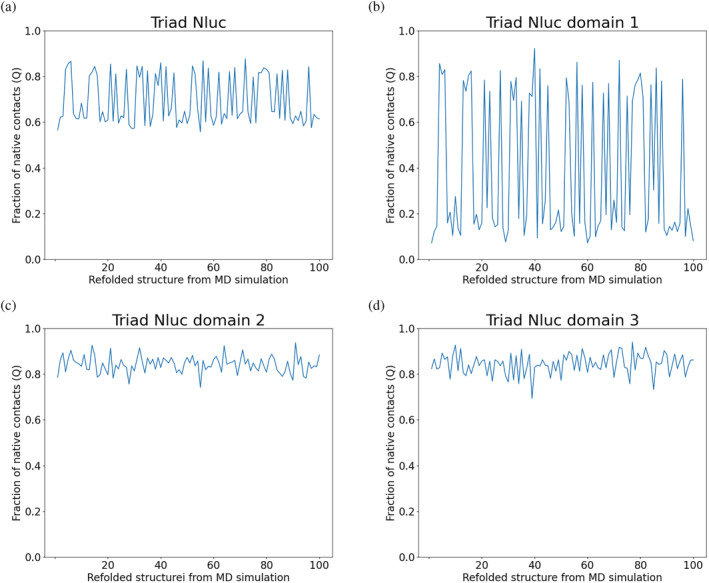

We also performed coarse‐grained simulations for the triad Nluc to examine its refolding (n = 100). The refolding results of the triad Nluc are displayed in Figure 8. As shown in Figure 8a, at least two domains are refolded correctly in most simulations. The fraction of native contacts is near 0.6 for 63 MD simulations, which means there is around 63% possibility for one domain to misfold. Another 37 MD simulations lead to the fully refolded structure. Figure 8b–d corresponds to refolding results for domain #1 (residue 23–193), domain #2 (residue 198–368), and domain #3 (residue 373–543), respectively. Domain 2 and domain 3 are always correctly refolded to native structures, while domain 1 is misfolded in 63 out of 100 simulations.

FIGURE 8.

Coarse‐grained simulations of refolding of the triad Nluc (n = 100) show a 63% possibility of correct refolding (a). Domain 1 (residue 23–193) is misfolded in 63 of 100 simulations, while (c) domain 2 (residue 198–368) and (d) domain 3 (residue 373–543) are always correctly refolded in all 100 simulations according to the fraction of native contacts (Q). In all figures, we compare native contacts of the initial and final structure per simulation.

We also examined the possibility of domain swapping for the dyad and triad Nluc computationally based on the fact that these constructs consist of tandem domains of the same protein. First, we applied the Tandem Domain Swap Stability Predictor (TADOSS) to calculate the domain‐swapped propensity (Lafita et al., 2019a). The calculated free energy difference ΔΔG between the native structure and domain‐swapped structure for the dyad Nluc is −0.94 kJ/mol, which means the native structure is slightly more stable than the domain‐swapped structure, even though the difference is small.

Next, we performed refolding simulations with domain‐swapping contacts. As shown in Figure S4a, the fractions of native contacts are closer to 0.5 with domain swapping contacts for dyad Nluc, which means almost all simulations have a result of one misfolded domain. Different from the results without domain swapping, the misfolded domain is random, that is, either domain 1 or domain 2, according to Figure S4b,c. Some fractions of native contacts are not closer to 0.8 or 0.2, which is because of some small extents of domain swapping, as shown in Figure S4b,c. The percentage of domain swapping is not high in dyad Nluc, meaning that most of one domain is refolded, and another misfolded domain has a few contacts with the refolded domain (Figure S4d). A structure of the domain swapping generated from these simulations for dyad Nluc can be seen in Figure 9.

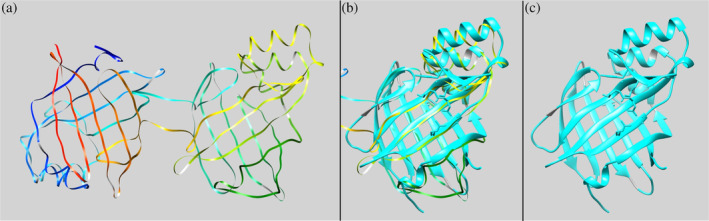

FIGURE 9.

TADOSS prediction results for dyad Nluc (n = 50). (a) Depiction of the dyad Nluc for one of the Tandem Domain Swap Stability Predictor (TADOSS) simulations (rainbow ribbons). (b) Overlapping of one of the acquired predicted structures after TADOSS simulations shown in (a) with monomeric Nluc (PDB code 5IBO, cyan ribbons). (c) Monomeric Nluc (PDB code 5IBO, cyan ribbons). All structures are visualized using the UCSF Chimera program. The orientation of structures is the same for all (a)–(c) images to show the overlap. We implemented the matchmaker command in UCSF Chimera to overlap the two structures.

The refolding results of the triad Nluc with domain swapping contacts are displayed in Figure S5. As shown in Figure S5a, the fractions of native contacts are also closer to 0.5, which means almost all simulations only have one correctly refolded domain, since the other two misfolded domains will also have a few native contacts. The result is different from the result without domain swapping contacts, which is likely to have two correctly refolded domains and one misfolded domain. Figure S5b–d corresponds to refolding results for domain 1 (residue 23–193), domain 2 (residue 198–368), and domain 3 (residue 373–543), respectively. The refolded domain can be arbitrary, but the other two domains are then misfolded. As displayed in Figure S5e, the percentage of domain swapping is around 0.4, which suggests the non‐negligible domain swapping contacts between the two misfolded domains. A structure of the domain swapping generated from these simulations for dyad Nluc can be seen in Figure 10. At this point, our CG simulations suggest two possible major misfolding scenarios for Nluc triads; intradomain misfolding and interdomain strands swapping. Further combined computational and experimental work is warranted to clarify which of these two pathways (if any) is dominant.

FIGURE 10.

TADOSS prediction results for triad Nluc (n = 50). (a) Depiction of the triad Nluc for one of the Tandem Domain Swap Stability Predictor (TADOSS) simulations (rainbow ribbons). (b) Overlapping of one of the acquired predicted structures after TADOSS simulations shown in (a) with monomeric Nluc (PDB code 5IBO, cyan ribbons). (c) Monomeric Nluc (PDB code 5IBO, cyan ribbons). All structures are visualized using the UCSF Chimera program. The orientation of structures is the same for all (a)–(c) images to show the overlap. We implemented the matchmaker command in UCSF Chimera to overlap the two structures.

2.7. All‐atom simulations

In order to identify Nluc regions most susceptible to thermal denaturation, we also conducted all‐atom melting simulations for monomeric and dyad Nluc, solvated in a water box, using explicit water model TIP3P. The thermal denaturation temperatures were for both proteins 350 K, 410 K, 440 K, 450 K, 475 K, and 500 K, and the total run time was 400 ns. For the all‐atom simulations, we performed root mean squared deviation (RMSD) analysis for all simulations (see Section 4, Figure S6), and using the MDAnalysis Python package, we attempted to identify the residues with the greatest fluctuation, by calculating the root mean squared fluctuation (RMSF) of each residue (Figure S7). Key findings from the timeline of our all‐atoms simulations indicate that the αΙΙ helix (residues 27–36) appears to be the first to lose its structure. As the temperature increases the αΙΙΙ and αΙV helices (residues 63–78) also lose their structure. This is especially important given that these helices are structurally close to the furimazine binding site, which involves residues in the βB, βC, βD’, and βD strands (Nemergut et al., 2023). All four α‐helices (αΙ–αΙV helices) are close to one another and are also located in between the βA‐βB strands, and βC‐βD strands. Therefore, any loss in the structure of the α‐helices can negatively affect the way the BL substrate can tightly bind to Nluc to produce light. The tightness of this binding site was also demonstrated in recent work, which showed that Nluc has two conformations, open and closed β‐barrel, with the closed β‐barrel having the tighter fit for the substrate in the binding pocket (Nemergut et al., 2023). More details on the all‐atom simulations can be found in Appendix S1.

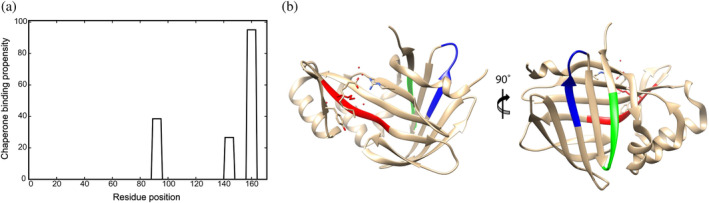

Previous screening of biologically relevant proteins showed that chaperones recognize hydrophobic surfaces and usually protein sequences that occur approximately every 30–40 residues in the total protein sequence (Clerico et al., 2021; Mayer, 2018; Rüdiger et al., 1997), instead of the complete protein structure. We investigated the binding sites of DnaK to Nluc by inserting the Nluc sequence into the LIMBO prediction algorithm (Van Durme et al., 2009). In our case, we were able to identify three DnaK‐binding motifs in Nluc as shown in Figure 11. The sequences are (a) residues 89–95 “FKVILHY” (score 12.2), (b) residues 141–147 “ERLINPD” (score 12.2), and (c) residues 157–163 “NGVTGWR” (score 14.4). We did not experimentally examine the validity of these sites, however, we expect them to be a good prediction for our system.

FIGURE 11.

DnaK‐binding motifs in Nluc. (a) Results of the LIBMO prediction algorithm for Nluc protein showed three DnaK‐binding motifs a) residues 89–95 “FKVILHY” (score 12.2), (b) residues 141–147 “ERLINPD” (score 12.2), (c) residues 157–163 “NGVTGWR” (score 14.4). (b) The DnaK‐binding motifs are marked with different colors on the crystal structure of the protein (PBD code 5IBO), with (a) residues 89–95 colored in red, residues 141–147 colored in blue, (c) residues 157–163 colored in green.

Therefore, by combining our findings we can hypothesize that possible loss in the helical structures may cause a loss in bioluminescence from our constructs and simultaneously expose residues 89–95 “FKVILHY”. DnaK, according to LIMBO algorithm prediction, may bind onto these residues and therefore rescue the Nluc structure from misfolding by allowing the neighboring structures to be refolded back to their native state, bringing back the BL signal. Monitoring the simulations at their later stages they show the further loss in the protein's structure exposing the other two binding motifs to DnaK. However, significantly longer all‐atom simulations will be needed to extrapolate and compare their results with the results produced by CG simulations to ultimately identify the misfolded ensemble at the residue level that the chaperones rescued in our experiments.

2.8. CD measurements of monomeric and triad Nluc

In our attempts to gain some insight into Nluc structural dynamics after exposing it to elevated temperatures, we carried out circular dichroism measurements on our Nluc constructs at room temperature and after heating the samples to 58°C and subsequent cooling back to room temperature (25°C) (Appendix S1). For these measurements, we had to use significantly increased protein concentrations and different buffers without stabilizing agents such as DTT and Tween 20, which all seem to adversely affect our results as discussed in Appendix S1. Nevertheless, some interesting observations from these measurements may be derived. CD measurements captured a significant structural alteration in the monomeric Nluc at 58°C. However, in contrast to refolding measurements, as evaluated by the BL signal, the monomeric Nluc did not refold after reducing the temperature from 58 to 25°C under CD experimental conditions. We hypothesize that at 1 μM Nluc concentration, the aggregation of unfolded Nluc may inhibit its spontaneous refolding. Interestingly, the triad Nluc, as judged by the CD signal, seems to experience little structural alteration at 58°C. This at first, seems to contradict our observations based on the BL measurements after thermal denaturation, which clearly indicate that triad Nluc misfolds permanently at 58°C, and does not refold spontaneously at 25°C, even after 7 h. It is difficult to reconcile this permanent misfolding with the “slight structural changes” suggested by the CD data. A possible explanation for this conundrum is that the triad Nluc, similar to monomeric Nluc, experiences significant structural alterations at 58°C, however, these alterations convert into permanent misfolding that preserves most of the beta structure of the triad and thus are not captured by CD at our sensitivity and resolution. Domain swapping within the Nluc triad suggested by MD simulations would be consistent with these complex results.

3. CONCLUSIONS

In the work presented here, we aimed to examine if bioluminescent Nluc, with its distinct biophysical and structural features, could be a substrate for the Hsp70 chaperone system (Szabo et al., 2006). We started our studies by using three constructs based on Nluc: monomeric Nluc, dyad Nluc, and triad Nluc, with the latter two comprised of two and three tandem repeats of Nluc within a single polypeptide chain. The dyad and triad Nluc constructs discussed in this work are the first bioluminescent polyprotein constructs that were thermally denatured and refolded using the E. coli Hsp70 system. With about 70% of eukaryotic proteins and 60% of prokaryotic proteins composed of multiple domains or repeats (Han et al., 2007; Rebeaud et al., 2021), our assay could be useful in examining nuances of the chaperone mechanism involved in refolding of complex multi‐domain proteins. Also, because Nluc's thermal stability is significantly greater as compared to other substrates, our assay could be implemented to examine the chaperone mechanism in thermophiles. One of the more interesting aspects of our study is the observation that GrpE is not essential in the refolding of poly‐Nluc. This warrants further investigations and possibly opens new mechanistic questions on how Hsp70 interacts with polyproteins.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Protein engineering

Nluc's sequence was obtained from Protein Data Bank (PDB code 5IBO) and its coding sequence was acquired from Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. (Research Triangle Park, NC). We provided this sequence to GenScript Biotech (Piscataway, NJ) for the synthesis of the various constructs used in this study. The template plasmid for all constructs was pEMI91 (Scholl et al., 2016). For the monomeric, dyad, and triad Nluc constructs the poly I91 domains in pEMI91 were replaced by Nluc proteins keeping the His6‐Tag and Strep‐Tag at the N and C termini, respectively. Codon shuffling was performed for the individual Nluc repeats for the dyad Nluc and triad Nluc constructs by GenScript allowing sequencing of the entire protein gene. For the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct (Apostolidou et al., 2022) the I91 domains in the construct were used. The resulting constructs are shown in Figure 12.

FIGURE 12.

Sequence of protein constructs for monomeric, dyad, and triad Nluc and I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 proteins. All constructs have starting from the N‐terminus a His‐Tag (blue letters), a thrombin site (yellow letters), the Nluc sequence (red letters), and a StrepTag II (green letters). For the I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91‐Nluc‐I91 construct, there are also the I91 titin domains (magenta letters).

4.2. Protein purification

For protein expression, we used BL21‐Gold (DE3) competent cells (Agilent). After transformation, single colonies were picked to grow into starter cultures that were later transferred into 500 mL (37°C). LB media was used in every step with ampicillin for antibiotic resistance. When each 500 mL bacterial culture reached an OD of 0.8, it was brought down to room temperature and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 3 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 30 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 5 mL resuspension buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole), followed by immediate flash freezing in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until purification.

All cells were lysed on ice by the addition of 20 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole at pH 8.0, protease inhibitor cocktail EDTA‐Free, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, 3 units/mL benzonase, 1 mM DTT, and 0.5% Triton X‐100). Gravity flow columns were used for all four protein constructs for binding the His‐Tag of the proteins to the Ni‐NTA Agarose (Qiagen). All buffers used were according to the guidelines of the manufacturer. The purified Nluc was dialyzed using SnakeSkin Dialysis Tubing (ThermoFisher Scientific) in Buffer A (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT) and flash frozen at ∼1 mg/mL ready for experiments.

DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE were purified in Dr. Qinglian Liu's laboratory following the procedures described before (Sarbeng et al., 2015) and shipped on dry ice from VCU to Duke University, where they were stored at −80°C until use.

4.3. Protein denaturation, renaturation, and bioluminescence assay experiments

The various Nluc constructs at 100 nM were thermally denatured at 58°C or 65°C in Buffer B (25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 0.05% T20). Spontaneous refolding was initiated by 10‐fold dilution of the denatured proteins in refolding Buffer C (25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 0.05% Tween 20, 5 mM ATP, 10 mM Mg(OAC)2). Chaperone assisted refolding was initiated by 10‐fold dilution of the proteins in Buffer C already including DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE at the reported concentrations per experiment. Additionally, various concentrations of BSA (Bio‐Rad Laboratories) were added in Buffer C with or without chaperones to study the effects of crowding on protein renaturation. All refolding reactions were performed at room temperature. BL measurements at different time points were collected by doing a 10‐fold dilution (1 nM of protein) of the refolding reactions (spontaneous or chaperone assisted) in Buffer B due to the high BL signal at 10 nM of the proteins. The diluted 1 nM protein solution (50 μL) was combined with 50 μL of Nano‐Glo Luciferase Assay (Promega Company) and the reaction was allowed to equilibrate for 3 min, as per manufacturer instructions, before collecting the BL value. All BL measurements were conducted using a GlowMax 20/20 Luminometer with 10 s of averaging (Promega Company, model E5311).

Apart from Nluc constructs, we also performed chaperone‐assisted refolding of Fluc (QuantiLum Recombinant Luciferase, Promega Company) that served as controls and benchmark measurements for Nluc experiments. For these experiments, 80 nM of Fluc together with 3 μΜ DnaK, and 1 μΜ DnaJ were heat shocked at 42°C in Buffer C (no T20 added) with later addition of 3 μM GrpE whenever mentioned. For BL signal at various time points, 5 μL of Fluc and chaperones sample was mixed with 50 μL of luciferase (Luciferase Assay System E1500, Promega Company). BL signal was immediately collected using the same luminometer as for Nluc constructs with the same 10 s averaging time.

Collected curves for chaperone‐assisted refolding were fitted using the equation. Similarly, we fitted the thermal denaturation curves using the , since the two‐parameter equation did not accurately fit the data. In both cases, the SigmaPlot program was used for data analysis.

4.4. ATPase activity of DnaK via colorimetric determination

ATP hydrolysis experiments were performed in the same conditions as our refolding assays described in Section 4.3 from Materials and Methods. We used the Malachite Green Phosphate Assay Kit from Sigma‐Aldrich (MAK307) for the ATPase assay and prepared the Malachite reagent as per manufacturer's instructions. A 96‐well plate with flat bottom and the Biotek Synergy‐2 plate reader were used. Due to the saturation of the signal, before every measurement, the protein refolding solution was diluted four‐times by adding 15 μL of the reaction solution to 45 μL of Buffer B. To the 60 μL of diluted reaction, we added 15 μL of Malachite Green reagent. The reaction was well mixed and incubated at room temperature for 30 min before collection of the OD at 630 nm as per manufacturer's instructions. These conditions were examined: (a) triad Nluc in the presence of 3 μM DnaK, 1 μM DnaJ, and 1.5 μM GrpE, (b) triad Nluc in the presence of 3 μM DnaK, and 1 μM DnaJ, and (c) 3 μM DnaK, 1 μM DnaJ, and 1.5 μM GrpE in the absence of triad Nluc.

Additionally, a phosphate standard curve was obtained using the phosphate standard in the Malachite Green Phosphate Assay Kit. The phosphate standard was diluted in Buffer B, and 60 μL of phosphate solution at different concentrations was added along with 15 μL of Malachite Green reagent. We used the same incubation times, plate, and plate reader as mentioned above.

4.5. Circular dichroism experiments

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were collected on an AVIV 435 Spectrometer along with a Hellma QS 1.000 cuvette and an optical path length of 10 mm, with stopper. A magnetic stirrer was used to mix the protein solution during the thermal denaturation (speed 50), and the temperature was closely controlled by a sensor allowing a 0.10°C error in the temperature. Monomeric Nluc was at 1 μM concentration during the experiments. For the dyad and triad Nluc proteins, we adjusted the protein concentration to result in same total mass of Nluc protein for all three proteins per experiment. All proteins were in 2.5 mL during CD. For every protein construct, we started our experiments at 25°C and collected the spectrum of all three native proteins. Then we increased the temperature with a 5°C step increase up to 58°C. Proteins were kept at 58°C for 10 min, following our thermal denaturation protocol, and three consecutive spectra were collected from 204 to 300 nm with 2 nm as the step size (averaging time for every point was 6 s). For all proteins, we used 25 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) and 100 mM KCl. Buffer B was not chosen due to strong absorbance at lower wavelengths impeding the experiment. Addition of DTT and TCEP also resulted in absorbance at lower wavelengths, therefore, we decided to not use them in our CD experiments.

4.6. Coarse‐grained MD simulations

All simulations were performed in GROMACS 2018.2 (Abraham et al., 2015). The initial all‐atom structures of monomeric, dyad, and triad Nluc were prepared based on the following sequences: (1) monomeric Nluc: MGSS‐HHHHHH‐SSG‐LVPRGS‐HELM‐NLuc‐TSRT‐WSHPQFEK‐CCMH; (2) dyad Nluc: MGSS‐HHHHHH‐SSG‐LVPRGS‐HELM‐NLuc(1)‐LEGSM‐NLuc(2)‐ASRT‐WSHPQFEK‐CCMH; (3) triad Nluc: MGSS‐HHHHHH‐SSG‐LVPRGS‐HELM‐NLuc(1)‐LEGSM‐NLuc(2)‐ASGSM‐NLuc(3)‐TSRT‐WSHPQFEK‐CCMH. All‐atom simulations were then performed for each system to generate the native structures. CHARMM36 protein force field (Best et al., 2012) and the TIP3P water model (Jorgensen et al., 1983) were used in all‐atom simulations. First, the steepest descent algorithm was applied for energy minimization, which converges when the maximum force is smaller than 1000 kJ/mol/nm. Next, a 1 ns NVT simulation using a v‐rescale thermostat (Bussi et al., 2007) and a 2 ns NPT simulation using a Parrinello‐Rahman barostat (Parrinello & Rahman, 1981) were performed successively to equilibrate the system. For every all‐atom simulation, the integration time step was set to 2 fs. We set 1.2 nm for the cutoff of short‐range electrostatic interaction and Van der Waals interaction, and specified particle mesh Ewald (Darden et al., 1993) method for long‐range electrostatic calculation. Bonds involving hydrogens were constrained using the LINCS algorithm (Hess et al., 1997).

After the all‐atom simulations were finished, the coarse‐grained models were constructed from the final equilibrated all‐atom models using Cα native structure‐based force fields (Clementi et al., 2000) on the SMOG server (Noel et al., 2016). The temperature for coarse‐grained MD simulations was determined using the same method in previous work (Scholl et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2020). The protein was first denatured at 300 temperature units with a 100 ns simulation and subsequently refolded at 5 different temperature units, which are 130, 140, 150, 160, and 170. Based on the similar probabilities for folded and unfolded states, the 150 temperature unit was finally selected as the temperature for coarse‐grained simulations. The integration time step, the cutoff of Van der Waals interaction, and the simulation time were set to 0.5 fs, 3.0 nm, and 500 ns, respectively, for all coarse‐grained refolding simulations. We performed 100 simulations for monomeric Nluc, dyad Nluc, and triad Nluc, starting from random unfolded structures in the trajectories of denaturing simulations.

The fraction of native contacts, denoted as Q, is a number between 0 and 1, and calculated as the total number of native contacts in the final refolded structures divided by the total number of native contacts in the reference native structures, which provides some insights on the extent of refolding and misfolding.

Besides the normal refolding simulations, we also investigated tandem domain swaps (Lafita et al., 2019b) with coarse‐grained simulations. All the simulation parameters are the same as the normal refolding simulations, except that we complemented native contacts in topology to include domain‐swapping effects. For each contact between residue i and residue j in one Nluc domain, and the corresponding contact between residue i′ and residue j′ in another Nluc domain, the inter‐domain contact between residue i and residue j′, as well as the contact between residue i′ and residue j, were included in the domain‐swapping simulations (Terse & Gosavi, 2021). We performed 50 simulations for dyad Nluc and triad Nluc with the domain‐swapping contacts.

4.7. All‐atom simulations

All‐atom simulations were performed on the monomeric and dyad Nluc constructs to examine their thermal stability at various temperatures. The protein structure was obtained using PDB code 5IBO. Formation of the dyad Nluc structure was obtained using UCSF Chimera by connecting the two monomeric Nlucs. For the linkers, we used the Chimera addaa method (Pettersen et al., 2004). This resulted in 171 and 346 residues for the monomeric and dyad Nluc proteins, respectively. The linkers used for the dyad Nluc were the same as in the protein construct for thermal denaturation (residues LEGS, Figure 12). The water boxes for the two proteins were for monomeric Nluc 8.0 x 8.6 x 9.3 nm3 (system size ~61,400 atoms) and for dyad Nluc 12.6 x 10.8 x 9.8 nm3 (system size ~127,800 atoms) to allow full expansion of the proteins during thermal denaturation, during which process proteins lose their core packing and, therefore, their secondary structure. In all simulations, the of methionine (#1) was fixed allowing the utilization of an optimal water box without limiting the quality of the simulations. NAMD 2.12 or 2.14 with CUDA GPU acceleration were used along with Charm 36 (par_all36m_prot.prm) (Best et al., 2012), TIP3P water model (Jorgensen et al., 1983), and the addition of ions at a concentration of 150 mM NaCl. The NPT ensemble was applied for all thermal denaturation simulations with a Nóse−Hoover Langevin piston pressure control and Langevin dynamics for temperature control. Periodic boundaries were applied. For the monomeric Nluc we ran simulations at 350 K, 410 K, 440 K, 450 K, 475 K, and 500 K. Similarly, for dyad Nluc we ran simulations at 410 K, 440 K, 450 K, 475 K, and 500 K. During each run of the simulation, we also did equilibration for the first 100 ns and then the simulation was allowed to continue. The total run time was 400 ns. RMSD for all simulations was collected using VMD. Additionally, in our analysis, we implemented the MDAnalysis Python (Gowers et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2010; Michaud‐Agrawal et al., 2011; Theobald, 2005; van der Walt et al., 2011) package following the instructions on website (https://www.mdanalysis.org/) for RMSF calculations.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dimitra Apostolidou: Methodology; validation; formal analysis; investigation; resources; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; software; data curation; visualization; supervision. Pan Zhang: Methodology; validation; formal analysis; investigation; writing – original draft; software; data curation; visualization. Devanshi Pandya: Methodology; formal analysis; investigation; writing – original draft; software. Kaden Bock: Methodology; formal analysis; software. Qinglian Liu: Resources; writing – review and editing. Weitao Yang: Resources; supervision. Piotr Marszalek: Conceptualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; project administration; resources; supervision; funding acquisition.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation, grant number MCB 1817556 and MCB 2118357. We would also like to acknowledge Prof. Terrence G. Oas (Duke University) for assisting with CD experiments, and Prof. Jason E Gestwicki (UCSF) for assisting with the Malachite Green Assay.

Apostolidou D, Zhang P, Pandya D, Bock K, Liu Q, Yang W, et al. Tandem repeats of highly bioluminescent NanoLuc are refolded noncanonically by the Hsp70 machinery. Protein Science. 2024;33(2):e4895. 10.1002/pro.4895

Review Editor: Aitziber L. Cortajarena

REFERENCES

- Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, et al. Gromacs: high performance molecular simulations through multi‐level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolidou D, Zhang P, Yang W, Marszalek PE. Mechanical unfolding and refolding of NanoLuc via single‐molecule force spectroscopy and computer simulations. Biomacromolecules. 2022;23(12):5164–5178. 10.1021/acs.biomac.2c00997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arhar T, Shkedi A, Nadel CM, Gestwicki JE. The interactions of molecular chaperones with client proteins: why are they so weak? J Biol Chem. 2021;297(5):101282. 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banecki B, Zylicz M. Real time kinetics of the DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE molecular chaperone machine action. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(11):6137–6143. 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen EB, Chang L, Gestwicki JE, Zuiderweg ERP. Solution conformation of wild‐type E. coli Hsp70 (DnaK) chaperone complexed with ADP and substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(21):8471–8476. 10.1073/pnas.0903503106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best RB, Zhu X, Shim J, Lopes PEM, Mittal J, Feig M, et al. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all‐atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side‐chain χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8(9):3257–3273. 10.1021/ct300400x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botello E, Harris NC, Sargent J, Chen WH, Lin KJ, Kiang CH. Temperature and chemical denaturant dependence of forced unfolding of titin I27. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113(31):10845–10848. 10.1021/jp9002356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehmer D, Gässler C, Rist W, Mayer MP, Bukau B. Influence of GrpE on DnaK‐substrate interactions. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(27):27957–27964. 10.1074/jbc.M403558200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Horwich AL. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell. 1998;92(3):351–366. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80928-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussi G, Donadio D, Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys. 2007;126(1):014101. 10.1063/1.2408420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calloni G, Chen T, Schermann SM, Chang H, Genevaux P, Agostini F, et al. DnaK functions as a central hub in the E. coli chaperone network. Cell Rep. 2012;1(3):251–264. 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D, Banerjee S, Chakraborty S, Chowdhury D, Haldar S. Direct observation of the mechanical role of bacterial chaperones in protein folding. Biomacromolecules. 2022;23(7):2951–2967. 10.1021/acs.biomac.2c00451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi C, Nymeyer H, Onuchic JN. Topological and energetic factors: what determines the structural details of the transition state ensemble and “en‐route” intermediates for protein folding? An investigation for small globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 2000;298(5):937–953. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerico EM, Meng W, Pozhidaeva A, Bhasne K, Petridis C, Gierasch LM. Hsp70 molecular chaperones: multifunctional allosteric holding and unfolding machines. Biochem J. 2019;476(11):1653–1677. 10.1042/BCJ20170380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerico EM, Pozhidaeva AK, Jansen RM, Özden C, Tilitsky JM, Gierasch LM. Selective promiscuity in the binding of E. coli Hsp70 to an unfolded protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(41):1–11. 10.1073/pnas.2016962118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya V, Rutz DA, Moessmer P, Mühlhofer M, Lawatscheck J, Rief M, et al. The switch from client holding to folding in the Hsp70/Hsp90 chaperone machineries is regulated by a direct interplay between co‐chaperones. Mol Cell. 2022;82(8):1543–1556.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98(12):10089–10092. 10.1063/1.464397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Apostolidou D, Marszalek P. Mechanical stability of a small, highly‐luminescent engineered protein NanoLuc. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):55. 10.3390/ijms22010055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England CG, Ehlerding EB, Cai W. NanoLuc: a small luciferase is brightening up the field of bioluminescence. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27(5):1175–1187. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos C, Welch WJ. Role of the major heat shock proteins as molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:601–634. 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.003125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowers R, Linke M, Barnoud J, Reddy T, Melo M, Seyler S, et al. MDAnalysis: a python package for the rapid analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. Proceedings of the 15th python in science conference (Scipy); 2016. p. 98–105. 10.25080/Majora-629e541a-00e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MP, Unch J, Binkowski BF, Valley MP, Butler BL, Wood MG, et al. Engineered luciferase reporter from a deep sea shrimp utilizing a novel imidazopyrazinone substrate. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7(11):1848–1857. 10.1021/cb3002478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J‐H, Batey S, Nickson AA, Teichmann SA, Clarke J. The folding and evolution of multidomain proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(4):319–330. 10.1038/nrm2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison CJ, Hayer‐Hartl M, Di Liberto M, Hartl FU, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the nucleotide exchange factor GrpE bound to the ATPase domain of the molecular chaperone DnaK. Science. 1997;276(5311):431–435. 10.1126/science.276.5311.431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer‐Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475(7356):324–332. 10.1038/nature10317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson WA. Theory of allosteric regulation in Hsp70 molecular chaperones. QRB Discovery. 2020;1(1):1–30. 10.1017/qrd.2020.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comput Chem. 1997;18(12):1463–1472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imamoglu R, Balchin D, Hayer‐Hartl M, Hartl FU. Bacterial Hsp70 resolves misfolded states and accelerates productive folding of a multi‐domain protein. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):365. 10.1038/s41467-019-14245-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Rossi P, Kalodimos CG. Structural basis for client recognition and activity of Hsp40 chaperones. Science. 2019;365(6459):1313–1319. 10.1126/science.aax1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79(2):926–935. 10.1063/1.445869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner MJ, Naylor DJ, Ishihama Y, Maier T, Chang HC, Stines AP, et al. Proteome‐wide analysis of chaperonin‐dependent protein folding in Escherichia coli . Cell. 2005;122(2):209–220. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kityk R, Kopp J, Mayer MP. Molecular mechanism of J‐domain‐triggered ATP hydrolysis by Hsp70 chaperones. Mol Cell. 2018;69(2):227–237.e4. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopish K, Hall M, Binkowski B, Valley M, Butler B, Machleidt T, et al. 188 NanoLuc: a smaller, brighter, and more versatile luciferase reporter. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:57. 10.1016/S0959-8049(12)71986-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lafita A, Tian P, Best RB, Bateman A. TADOSS: computational estimation of tandem domain swap stability. Bioinformatics. 2019a;35(14):2507–2508. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafita A, Tian P, Best RB, Bateman A. Tandem domain swapping: determinants of multidomain protein misfolding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2019b;58:97–104. 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberek K, Galitski TP, Zylicz M, Georgopoulos C. The DnaK chaperone modulates the heat shock response of Escherichia coli by binding to the σ32 transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(8):3516–3520. 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Agrafiotis DK, Theobald DL. Fast determination of the optimal rotational matrix for macromolecular superpositions. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(7):1561–1563. 10.1002/jcc.21439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mally A, Witt SN. GrpE accelerates peptide binding and release from the high affinity state of DnaK. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8(3):254–257. 10.1038/85002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashaghi A, Bezrukavnikov S, Minde DP, Wentink AS, Kityk R, Zachmann‐Brand B, et al. Alternative modes of client binding enable functional plasticity of Hsp70. Nature. 2016;539(7629):448–451. 10.1038/nature20137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew A, Morimoto RI. Role of the heat‐shock response in the life and death of proteins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;851(1 STRESS OF LIF):99–111. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08982.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer MP. Intra‐molecular pathways of allosteric control in Hsp70s. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2018;373(1749):20170183. 10.1098/rstb.2017.0183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer MP, Gierasch LM. Recent advances in the structural and mechanistic aspects of Hsp70 molecular chaperones. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(6):2085–2097. 10.1074/jbc.REV118.002810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud‐Agrawal N, Denning EJ, Woolf TB, Beckstein O. MDAnalysis: a toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 2011;32(10):2319–2327. 10.1002/jcc.21787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moessmer P, Suren T, Majdic U, Dahiya V, Rutz D, Buchner J, et al. Active unfolding of the glucocorticoid receptor by the Hsp70/Hsp40 chaperone system in single‐molecule mechanical experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(15):e2119076119. 10.1073/pnas.2119076119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemergut M, Pluskal D, Horackova J, Sustrova T, Tulis J, Barta T, et al. Illuminating the mechanism and allosteric behavior of NanoLuc luciferase. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):7864. 10.1038/s41467-023-43403-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel JK, Levi M, Raghunathan M, Lammert H, Hayes RL, Onuchic JN, et al. SMOG 2: a versatile software package for generating structure‐based models. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12(3):1–14. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes JM, Mayer‐Hartl M, Hartl FU, Müller DJ. Action of the Hsp70 chaperone system observed with single proteins. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):6307. 10.1038/ncomms7307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packschies L, Theyssen H, Buchberger A, Bukau B, Goody RS, Reinstein J. GrpE accelerates nucleotide exchange of the molecular chaperone DnaK with an associative displacement mechanism. Biochemistry. 1997;36(12):3417–3422. 10.1021/bi962835l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M, Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J Appl Phys. 1981;52(12):7182–7190. 10.1063/1.328693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perales‐Calvo J, Giganti D, Stirnemann G, Garcia‐Manyes S. The force‐dependent mechanism of DnaK‐mediated mechanical folding. Sci Adv. 2018;4(2):eaaq0243. 10.1126/sciadv.aaq0243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perales‐Calvo J, Muga A, Moro F. Role of DnaJ G/F‐rich domain in conformational recognition and binding of protein substrates. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(44):34231–34239. 10.1074/jbc.M110.144642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. UCSF chimera – a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politou AS, Thomas DJ, Pastore A. The folding and stability of titin immunoglobulin‐like modules, with implications for the mechanism of elasticity. Biophys J. 1995;69(6):2601–2610. 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80131-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebeaud ME, Mallik S, Goloubinoff P, Tawfik DS. On the evolution of chaperones and cochaperones and the expansion of proteomes across the tree of life. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118(21):e2020885118. 10.1073/pnas.2020885118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter K, Haslbeck M, Buchner J. The heat shock response: life on the verge of death. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):253–266. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohland L, Kityk R, Smalinskaitė L, Mayer MP. Conformational dynamics of the Hsp70 chaperone throughout key steps of its ATPase cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(48):2017. 10.1073/pnas.2123238119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig R, Nillegoda NB, Mayer MP, Bukau B. The Hsp70 chaperone network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(11):665–680. 10.1038/s41580-019-0133-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüdiger S, Germeroth L, Schneider‐Mergener J, Bukau B. Substrate specificity of the DnaK chaperone determined by screening cellulose‐bound peptide libraries respect to the bound folding conformer are only partly. EMBO J. 1997;16(7):1501–1507. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1169754/pdf/001501.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüdiger S, Schneider‐Mergener J, Bukau B. Its substrate specificity characterizes the DnaJ co‐chaperone as a scanning factor for the DnaK chaperone. EMBO J. 2001;20(5):1042–1050. 10.1093/emboj/20.5.1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R, Karzai AW, Mehl AF, McMacken R. DnaJ dramatically stimulates ATP hydrolysis by DnaK: insight into targeting of Hsp70 proteins to polypeptide substrates. Biochemistry. 1999;38(13):4165–4176. 10.1021/bi9824036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbeng EB, Liu Q, Tian X, Yang J, Li H, Wong JL, et al. A functional DnaK dimer is essential for the efficient interaction with Hsp40 heat shock protein. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(14):8849–8862. 10.1074/jbc.M114.596288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl ZN, Josephs EA, Marszalek PE. Modular, nondegenerate polyprotein scaffolds for atomic force spectroscopy. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17(7):2502–2505. 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl ZN, Yang W, Marszalek PE. Chaperones rescue luciferase folding by separating its domains. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(41):28607–28618. 10.1074/jbc.M114.582049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönfeld H‐J, Schmidt D, Schröder H, Bukau B. The DnaK chaperone system of Escherichia coli: quaternary structures and interactions of the DnaK and GrpE components. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(5):2183–2189. 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder H, Langer T, Hartl FU, Bukau B. DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE form a cellular chaperone machinery capable of repairing heat‐induced protein damage. EMBO J. 1993;12(11):4137–4144. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06097.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Rief M, Žoldák G. Direct observation of chemo‐mechanical coupling in DnaK by single‐molecule force experiments. Biophys J. 2022;121(23):4729–4739. 10.1016/j.bpj.2022.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan SR, Gillies AT, Chang L, Thompson AD, Gestwicki JE. Molecular chaperones DnaK and DnaJ share predicted binding sites on most proteins in the E. coli proteome. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8(9):2323–2333. 10.1039/c2mb25145k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A, Schroder H, Hartl FU, Bukau B, Langer T, Flanagan J. The ATP hydrolysis‐dependent reaction cycle of the Escherichia coli Hsp70 system DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;91(22):10345–10349. 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terse VL, Gosavi S. The molecular mechanism of domain swapping of the C‐terminal domain of the SARS‐coronavirus main protease. Biophys J. 2021;120(3):504–516. 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.11.2277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theobald DL. Rapid calculation of RMSDs using a quaternion‐based characteristic polynomial. Acta Crystallogr Sec A Found Crystallogr. 2005;61(4):478–480. 10.1107/S0108767305015266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theyssen H, Schuster HP, Packschies L, Bukau B, Reinstein J. The second step of ATP binding to DnaK induces peptide release. J Mol Biol. 1996;263(5):657–670. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tskhovrebova L, Trinick J. Properties of titin immunoglobulin and fibronectin‐3 domains. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(45):46351–46354. 10.1074/jbc.R400023200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Walt S, Colbert SC, Varoquaux G. The NumPy array: a structure for efficient numerical computation. Comput Sci Eng. 2011;13(2):22–30. 10.1109/MCSE.2011.37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Durme J, Maurer‐Stroh S, Gallardo R, Wilkinson H, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J. Accurate prediction of DnaK‐peptide binding via homology modelling and experimental data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(8):e1000475. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Liu QQ, Liu QQ, Hendrickson WA. Conformational equilibria in allosteric control of Hsp70 chaperones. Mol Cell. 2021;81(19):3919–3933.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.07.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch WJ, Brown CR. Influence of molecular and chemical chaperones on protein folding. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1996;1(2):109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner S, Nguyen TLL, Genest O. The bacterial Hsp90 chaperone: cellular functions and mechanism of action. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2021;75:719–739. 10.1146/annurev-micro-032421-035644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Wang D, Yang W, Marszalek PE. Piecewise all‐atom SMD simulations reveal key secondary structures in luciferase unfolding pathway. Biophys J. 2020;119(11):2251–2261. 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuravleva A, Clerico EM, Gierasch LM. An Interdomain energetic tug‐of‐war creates the allosterically active state in Hsp70 molecular chaperones. Cell. 2012;151(6):1296–1307. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuravleva A, Gierasch LM. Substrate‐binding domain conformational dynamics mediate Hsp70 allostery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(22):E2865–E2873. 10.1073/pnas.1506692112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkiewski M, Zhang T, Nagy M. Aggregate reactivation mediated by the Hsp100 chaperones. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;520(1):1–6. 10.1016/j.abb.2012.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylicz M, Wawrzynow A. Insights into the function of Hsp70 chaperones. IUBMB Life. 2001;51(5):283–287. 10.1080/152165401317190770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting Information