Abstract

Purpose In an era when trabeculectomy surgeries in the United States are on the decline, ophthalmology residents may have limited opportunities to practice surgical techniques critical to success. However, key steps of trabeculectomy surgery can be introduced in a wet laboratory using a simple surgical model based on food items.

Methods A fresh lime and chicken parts with skin, purchased from a grocery store, were utilized to practice trabeculectomy surgery. The white rind of a lime was used as a surrogate for human sclera and was incised to create a trabeculectomy flap. The flap was then successfully sewn down with 10–0 nylon suture using an operating microscope. The skin of the chicken part was used to re-create a fornix-based and limbus-based conjunctival incision, which was then sutured closed using 6–0 Vicryl suture. A survey of wet laboratory participants was conducted to assess the feasibility and efficacy of this technique.

Results Survey respondents were divided into two groups, those who had performed ≥40 incisional glaucoma surgeries and those who had performed <40. Both groups rated the simulation a 4 (mode) out of 5 in terms of how well it prepared them for glaucoma surgery on a human eye and how well the materials replicated human tissue, with 1 being not at all and 5 being very well. Similarly, both groups rated ease of setup and material acquisition a 1 out of 5, 1 being not difficult at all and 5 being extremely difficult. Also, 93.5% of the survey respondents recommended implementing this training model at other teaching hospitals, and none of the respondents recommended against it.

Conclusion This trabeculectomy teaching model is inexpensive, clean, and safe, and it provides a reasonably realistic substrate for surgical practice. It does not require cadaver or animal eyes, and no fixatives are needed, thus minimizing the risk of contact with biohazardous materials. Wet laboratory materials are easy to obtain, making this a practical model for practicing glaucoma surgery in both westernized and developing countries.

Keywords: trabeculectomy training, simulated trabeculectomy surgery, trabeculectomy wet laboratory, food surgery, resident surgical training, ophthalmology surgical training

Despite the rise of minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries, 1 trabeculectomy and glaucoma drainage device surgery are still the two primary incisional surgical approaches for management of intraocular pressure in cases of severe glaucoma. Both surgeries require skill in working in a small space with delicate tissues to create controlled aqueous flow. 2 While modern-day glaucoma surgeries are generally successful, several intraoperative and postoperative complications may occur, 3 and practice is a necessary prerequisite to preparing for surgery.

Training residents to perform trabeculectomy has multiple challenges. The skills utilized in these surgeries are unique, particularly creating a scleral flap and handling Tenon's fascia and conjunctiva. Trabeculectomy surgery has been documented to be less successful in the hands of surgeons-in-training than when performed by experienced surgeons. 4 In addition, the number of trabeculectomy surgeries performed on the Medicare population in the United States has declined in recent years, 5 which may limit resident opportunities for training. According to a 2005 survey, most ophthalmology residents were narrowly achieving the required surgical numbers as primary surgeons in glaucoma filtering procedures. 6 For residents training in 2009 to 2016, the average number of primary filtering surgeries decreased from 6.0 cases to 4.8 cases, with concurrent increases in primary glaucoma drainage implants from 4.5 cases to 6.3 cases. 7 To put those numbers into perspective, ophthalmology residents perform ∼13 times more primary cataract surgeries than trabeculectomy surgeries during residency. 8 The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the importance of wet laboratories for surgical training when many elective ophthalmic surgeries were cancelled or postponed. In addition, opportunities for accessible glaucoma surgery wet laboratory training are important in developing countries. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals recently adopted its first resolution to develop eye care in emerging nations, and it was noted that simulation training (wet laboratories, virtual reality) may be an important part of this. 9

Unlike cataract surgery, where there are a multitude of published models (animal eyes and virtual reality simulation), 10 11 only a few exist for practicing trabeculectomies. Costly synthetic eyes are available, as are cheaper pig 12 and goat eyes, though these require time and effort to obtain. 13 We propose a novel method that is easily accessible and inexpensive, requiring only a fresh lime and any chicken part with skin.

Methods

A wet laboratory for simulating trabeculectomy surgery was developed at the University of California, Davis Department of Ophthalmology & Vision Sciences. In addition, a survey was deployed to users of the wet laboratory to assess feasibility and efficacy of this technique. This study was exempt from the requirement for institutional review board approval because it did not involve human or animal research, and no personal health information was collected.

Wet Laboratory Materials

Fresh lime, any size but with thick rind (white layer under the skin)

Raw, unfrozen chicken (legs, thighs) with skin

Styrofoam board or head form

Forceps (0.12 forceps, 0.3 forceps, tyers)

6700 or 7500 Beaver blade, microcrescent blade, or blade of your choice

Westcott and Vannas scissors

Needle driver

Suture material (9–0 or 10–0 nylon, 6–0 or 7–0 silk or Vicryl)

Marking pen

Vegetable peeler

Surgical Technique

Material Preparation for Lime Scleral Flap Creation

Peel the skin (green outer layer) of the lime with a vegetable peeler. Remove only the green skin, leaving as much of the white rind in place as possible. Wait 10 to 15 minutes for the rind to dry.

Pin the lime into a Styrofoam head (or similar holder).

Using a marking pen, draw an approximately 12-mm circle on the lime to represent the corneal limbus. The lime rind (white part underneath the green skin) will represent the sclera.

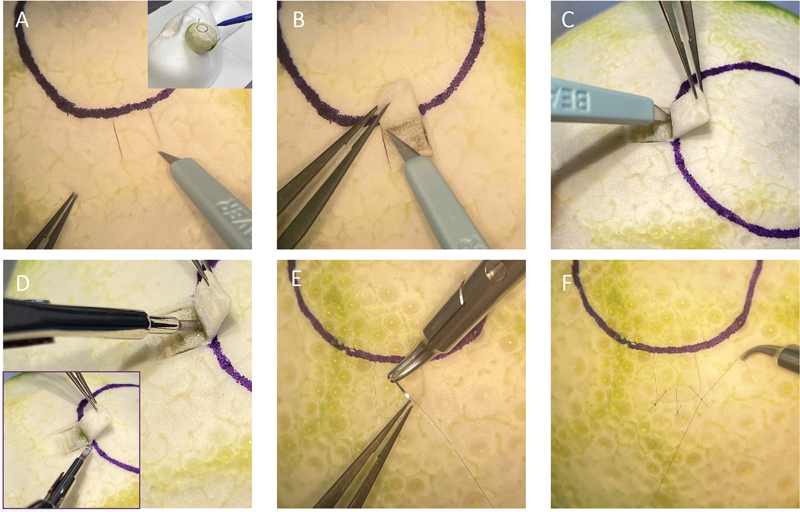

Creating and Suturing a Scleral Flap ( Fig. 1 )

Fig. 1.

Trabeculectomy scleral flap creation and closure simulation using a lime (suture, 10-nylon suture [Ethicon US, LLC, Cincinnati, OH]). ( A ) Creation of scleral flap. ( B ) Dissection of scleral flap. ( C ) Incision into the “anterior chamber.” ( D ) Punching the sclerostomy. ( E ) Suturing the scleral flap closed. ( F ) Tying the suture tight.

Create a flap that is three-fourths the depth of the “sclera” with any of the above-mentioned blades. If dissection is too deep, one will see a darkening of color, created by the green fruit, much in the same way one would see a color change from underlying uvea in the human eye. Common flap shapes are rectangular, trapezoidal, or triangular.

Suture the flap with 9–0 or 10–0 nylon suture. Place one suture in each corner of the flap. Practice placing sutures on the side of the flap.

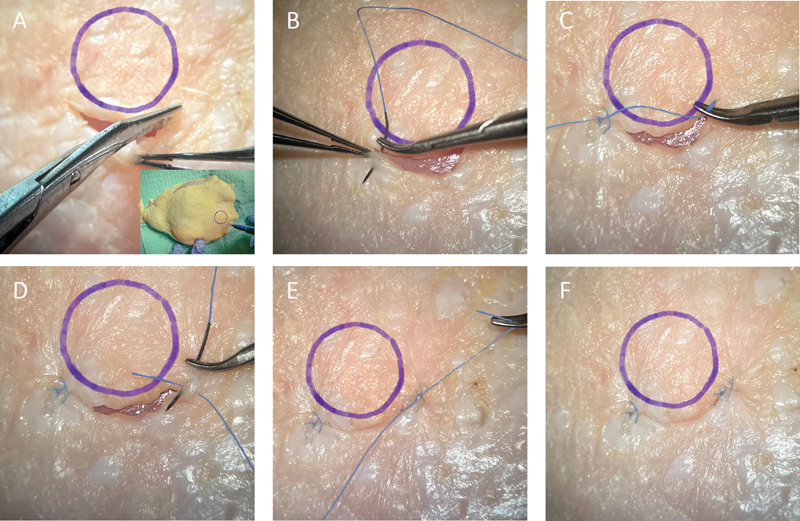

“Conjunctival” Sewing Using Chicken Skin ( Figs. 2 and 3 )

Fig. 2.

Fornix-based trabeculectomy conjunctival flap simulation with closure using chicken skin. ( A ) The conjunctiva is incised along the limbus. ( B, C ) A buried suture (6–0 Vicryl suture; Ethicon US, LLC, Cincinnati, OH) is used to appose the left side of the conjunctival flap to the limbus. ( D, E, F ) A similar suture is used to appose the right side of the conjunctival flap to the limbus to create a watertight closure.

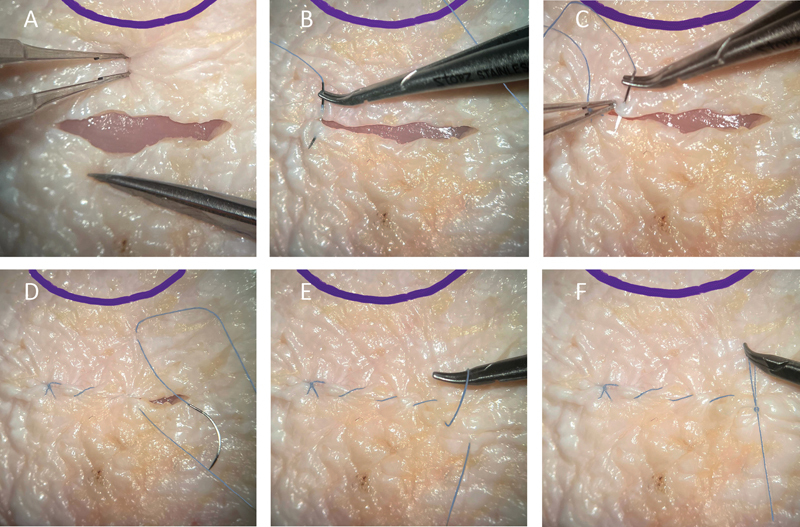

Fig. 3.

Limbus-based trabeculectomy conjunctival flap simulation with closure using chicken skin. ( A ) Westcott scissors are used to create a conjunctival incision 8 mm posterior to the limbus. ( B ) An anchoring suture (Ethicon US, LLC, Cincinnati, OH) is placed at the left side of the incision. ( C, D ) A running suture is used to close the incision. ( E ) A loop is created from the last running suture. ( F ) The loop is used to create the final knot to secure the running closure.

Using a marking pen, draw an approximately 12-mm circle on the chicken skin to represent the corneal limbus.

Fornix-based trabeculectomy incision: incise the chicken skin at the limbus and create a small peritomy. Use larger suture such as the 6–0 or 7–0 silk or Vicryl to sew the skin back to the limbus at each end, as shown in Fig. 2 .

Limbus-based trabeculectomy incision: cut a line in the chicken skin ∼8 mm posterior to the limbus, and then sew the skin together using a running suture pattern, as shown in Fig. 3 .

This training model has been utilized by residents and fellows at the University of California Davis Eye Center to practice their surgical techniques. A survey was developed by the authors using a Likert scale to assess the efficacy of the model in preparing eye surgeons for glaucoma surgery. It queried participants on the likeness of the simulation to surgery on a human eye, as well as whether this food model was preferred over animal eye models. This survey was sent by email to past participants in the wet laboratory simulation using Google Forms (Alphabet Inc., Mountainview, CA).

Results

A total of 31 participants who had performed the wet laboratory simulation responded to the survey. A summary of responses (expressed as the mode) is shown in Table 1 . The respondents were divided into two cohorts: those who had performed ≥40 glaucoma incisional surgeries and those who had performed <40.

Table 1. Ratings (mode) of survey respondents.

| All respondents ( n = 31) | Respondents who have performed ≥40 glaucoma incisional cases ( n = 18) | Respondents who have performed <40 glaucoma incisional cases ( n = 13) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How well did the simulation prepare you for glaucoma surgery on a human eye? (Scale of 1–5, 1 being not at all and 5 being very well) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| How well did the lime rind simulate human sclera? (Scale of 1–5, 1 being not at all and 5 being an exact replica) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| How well did the simulation prepare you for suturing human sclera? (Scale of 1–5, 1 being not at all and 5 being very well) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| How well did the chicken skin simulate human conjunctiva? (Scale of 1–5, 1 being not at all and 5 being an exact replica) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| How well did the simulation prepare you for suturing human conjunctiva? (Scale of 1–5, 1 being not at all and 5 being very well) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| How difficult was it to acquire the materials? (Scale of 1–5, 1 being not difficult at all and 5 being extremely difficult) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| How difficult was it to set up the simulation? (Scale of 1–5, 1 being not difficult at all and 5 being extremely difficult) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Comparison of Lime and Chicken Model to Animal Eyes and Likelihood of Recommending Wet Laboratory

A total of 50% of respondents preferred using limes over animal eyes for practicing incising and sewing scleral tissue, while 23.3% said both models were equally effective, and 23.3% preferred animal eyes. Similarly, 46.4% of respondents preferred using chicken skin over animal eyes for practicing conjunctival sewing techniques, while 32.1% said both models were equally effective, and 17.9% preferred animal eyes. Also, 93.5% of survey respondents said they would recommend implementing this training model at other residency programs or teaching hospitals, saying “the items are very easy to acquire,” “the tissue felt and behaved similar to human tissue,” and “the cleanup was easier” than with other models such as animal eyes. The remaining 6.5% of respondents were unsure whether they would recommend the simulation.

Discussion

Wet laboratory curricula have proven valuable in preparing inexperienced cataract surgeons for the operating room. 14 The skills required for trabeculectomy surgery can likewise be introduced in a wet laboratory. 13 14 Here, we present a wet laboratory teaching model for trabeculectomy that can be performed safely and with minimal preparation.

Currently, the proposed methods for trabeculectomy surgery training include using cadaver eyes, animal eyes, 12 13 synthetic models, and a fruit model. 15 The use of virtual reality simulators has been shown to improve trainee surgical outcomes in more common procedures, such as phacoemulsification, 11 but, to the best of our knowledge, no virtual trabeculectomy simulators exist, likely due to the lack of demand and high cost associated with the development of this technology. The use of cadaver and animal eyes has several disadvantages, including high cost, low availability, lack of viable conjunctiva, and potential contamination with infectious diseases. 16 The sclera of animal eyes (pig, sheep) is much tougher than that of human sclera, and preparation of cadaver eyes requires the use of potentially hazardous fixatives, such as formalin. Synthetic eye models can be used, but they are expensive and may not effectively replicate the feel of human eyes. 16

One other documented model for trabeculectomy utilizes simple household items (an apple wrapped in plastic cling wrap). 15 While these materials are easy to obtain, they do not adequately simulate the texture and feel of human tissue. We propose that the rind of a lime provides a closer simulation to human sclera, and that chicken skin affords a better model for practicing the suture techniques needed for conjunctival sewing.

The limitations of our practice method are that, while a lime rind closely simulates human sclera and chicken skin can provide a pragmatic substrate for sewing, they are not exact replicas of human tissues. In addition, if a lime with thin rind is chosen, the rind will not be thick enough to allow for the creation of a trabeculectomy flap.

Based on our survey results, most previous participants in this wet laboratory simulation found the proposed method to prepare them well for glaucoma surgery on a human eye, including the techniques of scleral and conjunctival suturing. Ratings did not seem to be affected by number of incisional glaucoma surgeries the respondent had performed in their careers. Participants found the materials easy to acquire and were able to set up the simulation without difficulty. A large majority of participants preferred this food model over animal eyes or found those two models to be equally effective. Furthermore, almost all the past participants (93.5%) would recommend implementing this training model at other teaching hospitals, and none of the respondents to the survey recommended against it. All results suggest this technique could be a valuable learning tool for ophthalmologists training both here in the United States and all over the world.

Conclusion

Our method of wet laboratory trabeculectomy practice requires key materials that are easy to obtain, inexpensive, clean, and safe. There is no significant preparation time, and the lime and chicken possess reasonably realistic tissue properties for practicing the construction and closure of a partial-thickness scleral flap and closure of conjunctiva.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Mr. Jim Hsu for photo editing.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Note

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the agencies they represent.

References

- 1.Chan C K, Lee S, Sangani P, Lin L W, Lin M S, Lin S C. Primary trabeculectomy surgery performed by residents at a county hospital. J Glaucoma. 2007;16(01):52–56. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000243473.59084.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cairns J E. Trabeculectomy. Preliminary report of a new method. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;66(04):673–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson P G, Jakeman C, Ozturk M, Barnett M F, Barnett F, Khaw K T.The complications of trabeculectomy (a 20-year follow-up) Eye (Lond) 19904(Pt 3):425–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biggerstaff K S, Vincent R D, Lin A P, Orengo-Nania S, Frankfort B J. Trabeculectomy outcomes by supervised trainees in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(08):669–673. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramulu P Y, Corcoran K J, Corcoran S L, Robin A L. Utilization of various glaucoma surgeries and procedures in Medicare beneficiaries from 1995 to 2004. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2265–2270. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golden R P, Krishna R, DeBry P W. Resident glaucoma surgical training in United States residency programs. J Glaucoma. 2005;14(03):219–223. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000159122.49488.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chadha N, Warren J L, Liu J, Tsai J C, Teng C C. Seven- and eight-year trends in resident and fellow glaucoma surgical experience. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:303–309. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S185529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowden A, Krishna R. Resident cataract surgical training in United States residency programs. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28(12):2202–2205. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flanagan J L, De Souza N. Simulation in ophthalmic training. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2018;7(06):427–435. doi: 10.22608/APO.2018129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruggiero J, Keller C, Porco T, Naseri A, Sretavan D W. Rabbit models for continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis instruction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(07):1266–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pokroy R, Du E, Alzaga A et al. Impact of simulator training on resident cataract surgery. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(03):777–781. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2160-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee G A, Chiang M YM, Shah P. Pig eye trabeculectomy-a wet-lab teaching model. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(01):32–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selvan H, Pujari A, Kishan A et al. Trabeculectomy on animal eye model for resident surgical skill training: the need of the hour. Curr Eye Res. 2021;46(01):78–82. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2020.1776880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee A G, Greenlee E, Oetting T A et al. The Iowa ophthalmology wet laboratory curriculum for teaching and assessing cataract surgical competency. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(07):e21–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porteous A M, Ahmed F. A novel wet-lab teaching model for trabeculectomy surgery. Eye (Lond) 2018;32(09):1537–1550. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walkden A, Au L, Fenerty C. Trabeculectomy training: review of current teaching strategies. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:31–36. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S168254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]