Abstract

The aim of this guideline is to provide a series of evidence-based recommendations that allow those new to using MEGA-PRESS to produce high-quality data for the measurement of GABA levels using edited magnetic resonance spectroscopy with the MEGA-PRESS sequence at 3T. GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system and has been increasingly studied due to its relevance in many clinical disorders of the central nervous system. MEGA-PRESS is the most widely used method for quantification of GABA at 3T, but is technically challenging and operates at a low signal-to-noise ratio. Therefore, the acquisition of high-quality MRS data relies on avoiding numerous pitfalls and observing important caveats.

The guideline was developed by a working party that consisted of experts in MRS and experts in guideline development and implementation, together with key stakeholders. Strictly following a translational framework, we first identified evidence using a systematically conducted scoping literature review, then synthesized and graded the quality of evidence that formed recommendations. These recommendations were then sent to a panel of 21 world leaders in MRS for feedback and approval using a modified-Delphi process across two rounds.

The final guideline consists of 23 recommendations across six domains essential for GABA MRS acquisition (Parameters, Practicalities, Data acquisition, Confounders, Quality/reporting, Post-processing). Overall, 78% of recommendations were formed from high-quality evidence, and 91% received agreement from over 80% of the expert panel.

These 23 expert-reviewed recommendations and accompanying extended documentation form a readily useable guideline to allow those new to using MEGA-PRESS to design appropriate MEGA-PRESS study protocols and generate high-quality data.

Keywords: GABA, MEGA-PRESS, 1H-MRS, MRS, Edited-MRS, Guideline

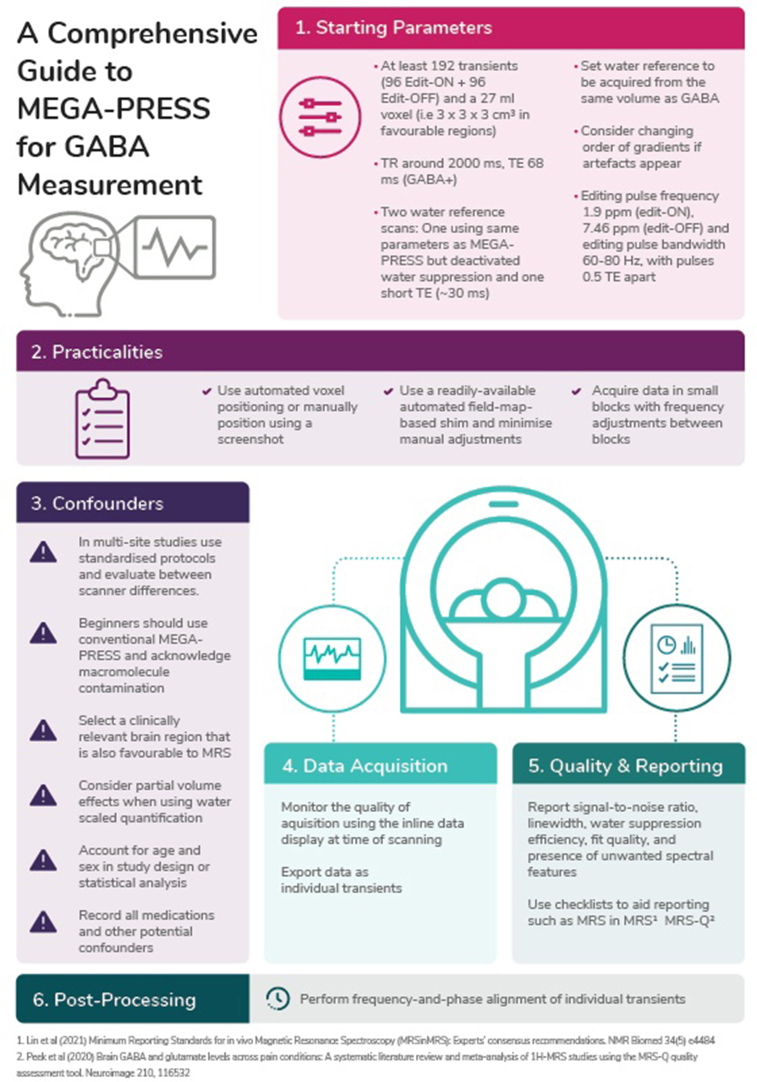

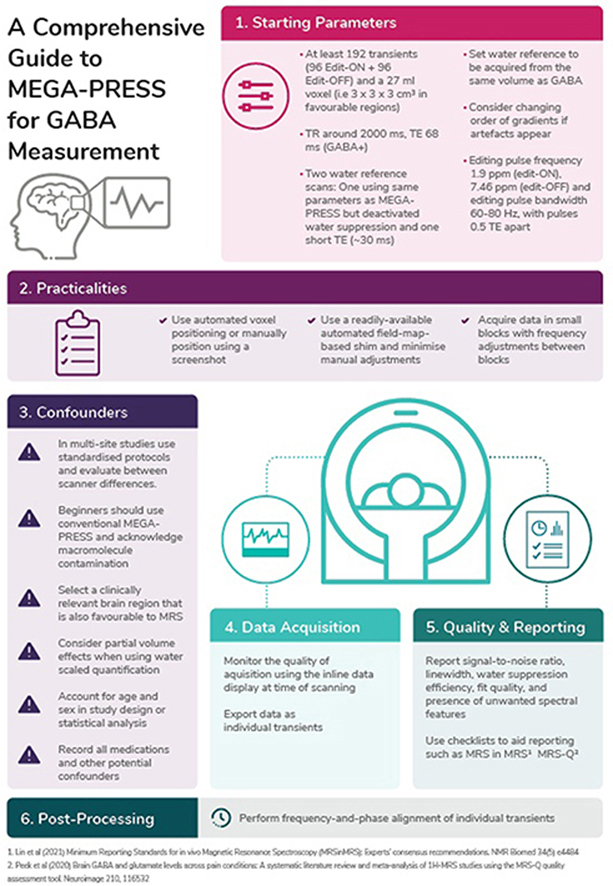

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Evidence-based, translational guideline for measuring GABA using MEGA-PRESS.

-

•

Developed using translational framework by end-users, MRS and implementation experts.

-

•

Contains 23 recommendations across six domains essential for GABA MRS.

-

•

Each recommendation was graded for quality of evidence and approval of 21 experts.

-

•

The package includes this manuscript, infographic and stylised extended guideline.

Abbreviations list

- CNS

Central Nervous system

- Cr

Creatine

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- GABA +

gamma-aminobutyric acid + macromolecules

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- HERMES

Hadamard Encoding and Reconstruction of MEGA-Edited Spectroscopy

- MEGA-PRESS

Mescher Garwood Point Resolved Spectroscopy

- MRS

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

- MRS-Q

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy quality assessment tool

- NAA

N-acetylaspartate

- NHMRC

National Health and Medical Research Council

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews

- SNR

signal-to-noise ratio

- TR

Repetition Time

- TE

Echo Time

1. Introduction

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system (CNS) and plays an important role in regulating healthy brain function. For example, GABA is implicated in sensory processing [1,2], learning [3,4], memory [5] and motor function [3,4]. GABA is of particular interest in clinical conditions of the CNS and altered GABAergic function has been associated with chronic pain [6], psychological disorders e.g. stress and depression [7,8], substance addiction [9] and neurodevelopmental disorders, e.g. autism spectrum disorder [10]. Evidence for altered GABA function comes through multiple lines of enquiry including animal models [11,12], genetics [13,14], post-mortem studies [15], blood plasma [16,17] and in-vivo Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) [6,18]. Given the wealth of evidence, targeting the GABAergic system with therapeutic interventions may therefore prove fundamental to improving patient outcomes in these conditions. However, this requires a better understanding of the role of GABA in humans, which requires the reliable measurement of GABA in the human brain. The only currently available approach to measure GABA in-vivo in humans is through tailored MRS.

MRS is a non-invasive brain imaging technique which enables the in-vivo quantification of endogenous brain neurometabolites based upon their chemical structure. Conventional proton MRS has been successfully used to quantify numerous neurometabolites, such as glutamate, N-acetylaspartate (NAA) and choline-containing compounds. GABA is also present in the MR spectrum, however, due to its lower concentration and complicated peak pattern, its signal is difficult to reliably separate from more abundant neurometabolites such as creatine [19]- particularly at field strengths typical for current clinical MRI scanners. The most widely used technique for measuring GABA levels at 3T is J-difference editing, most famously implemented in the MEscher–GArwood Point RESolved Spectroscopy (MEGA-PRESS) experiment [20]. MEGA-PRESS consists of two sub-experiments (usually acquired in an interleaved fashion), one applying editing pulses to H3 GABA protons at a frequency of 1.9 ppm to selectively refocus the coupling evolution of the H4 GABA signal at 3 ppm (‘Edit-ON’), while the other allows the free evolution of the spin system throughout the echo time (‘Edit-OFF’). Subtracting the Edit-OFF from the Edit-ON spectrum reveals a difference-edited GABA signal while removing the stronger overlapping signals from creatine-containing compounds (see Mullins et al., 2014 [19] for more details about the MEGA-PRESS pulse sequence and the GABA spin system). The edited signal at 3 ppm is contaminated by macromolecular signals (estimated to account for about 50% of the edited signal area) with the composite signal commonly referred to as GABA+. The 3 ppm macromolecular resonance is (similar to GABA itself) coupled to protons resonating at 1.7 ppm and therefore inadvertently “co-edited” as the 1.9 ppm editing pulses have finite selectivity. Adding a 1.5 ppm editing pulse in the ‘Edit-OFF’ experiment theoretically co-edits the same amount of macromolecules in both halves of the experiment and would allow to subtract them out [21], but the increased specificity comes at the expense of a much greater sensitivity to experimental instability, particularly thermal drift of the magnetic field strength [22].

The separability of the GABA signal is significantly improved using MEGA-PRESS, but accurate detection and quantification still require high-quality data. Data quality is determined to a great extent by the choice of acquisition parameters, however, few studies provide sufficient detail of these. For example, in a recent meta-analysis [6] investigating the use of MRS to measure GABA levels in pain conditions, only two out of fourteen studies reported using parameters that were deemed adequate for quantification of GABA levels. The remaining studies either documented using inadequate parameters or sequences, or altogether failed to fully report the parameters used, a finding resonated in other reviews such as Schur et al. 2016. The heterogeneity in MRS acquisition parameters used within the field has been acknowledged as a significant barrier to the reproducibility and comparability of quantitative MRS outcome measures [6,19]. In response, multiple expert panels have recently formed to establish consensus guidelines for minimal best practice in acquisition and analysis of MRS data [19,[23], [24], [25]]. While some aspects covered in these consensus guidelines might apply to GABA measurement using MEGA-PRESS, the specific requirements for its successful application are not addressed in detail.

A further barrier to implementing these consensus documents is that they are typically written by experts with a high level of technical knowledge, leading to some recommendations being difficult for those new to the field to interpret and adequately implement. The growing field of translational research has increasingly seen those from fields outside of magnetic imaging physics wishing to use advanced MRS methods in both clinical and research populations. Examples include clinician-researchers and higher degree research students in areas such as pain medicine, physiotherapy and psychology. Typically these researchers do not have a background in magnetic resonance physics, and often do not have direct access to the resources or expertise required to interpret and implement technical consensus documents. We have therefore identified a need for an easily accessible and translatable guideline to the adequate use of MEGA-PRESS for the measurement of GABA. However, the substantial heterogeneity in preferred acquisition parameters, even among leading MRS experts, is a challenge for creating widely applicable methodological guidelines.

We therefore used an established translational framework widely used for developing clinical guidelines in order to maximize the objectivity of our recommendations. The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the leading governmental authority on medical research in Australia, recommends a multi-stage process for guideline development [26]. Four key aspects to ensure robustness include: 1) engaging subject, and methodological expertise alongside end-users, 2) evidence synthesis, 3) establishing quality and strength of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [27], and 4) independent expert review of the recommendations [26,28]. These steps ensure guidelines are credible, useable and ready for implementation into practice.

The result of this study is a robust, translatable, evidence-based, and expert-reviewed guideline that will enable those new to the field of MRS to use MEGA-PRESS to acquire high-quality data for the reliable quantification of brain GABA levels. The adherence to a translational framework ensures that the guidelines are evidence-based, rather than a narrative of personal opinions and experiences. Whilst the guideline has been written specifically for the reliable measurement of GABA using MEGA-PRESS at 3T, many of the recommendations will, with certain modifications, also be applicable to similar techniques employing different signal localization (e.g. MEGA-sLASER, MEGA-SPECIAL [29]), editing schemes (HERMES) [30], and target metabolites [31].

2. Methods

We followed the NHMRC framework Guidelines for Guidelines [26] and utilized the ADAPTE toolkit [32] to develop this guideline. This framework divides the evidence synthesis and recommendation formation workflow into three stages: set up, adaptation and finalisation [32]. The stages are summarised in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Demonstrating the process followed to develop the guideline based on the ADAPTE process [32].

2.1. Set up

The purpose of the set up stage was to establish the guideline working party and sub-committees, identify key stakeholders and formulate a work plan [32].

2.1.1. Committee establishment and stakeholder engagement

The guideline working party included a core team of six co-authors. The working party consisted of two sub-committees; i) Guideline development/implementation sub-committee (four members- AL, AP, KR, TR with a total of over 40 years of experience in forming clinical/therapeutic guidelines) and ii) MRS sub-committee (three members- AP, GO, NP with a total of over 23 years experience in MRS of GABA). One author (AP) was included in both sub-committees to ensure consistency, communication and continuity across meetings. Key stakeholders reflect proposed end-users and those with an interest in the final guideline. Stakeholders were identified and engaged by the working party to be involved in the development process. The key stakeholders were a research radiographer, a PhD student studying MRS, three clinician-researchers who were investigating GABA levels in multiple pain conditions, and two MRS experts who provide training to new MRS users.

2.1.2. Work plan

A work plan identifying and recruiting all expertise required for project completion through large international collaborative networks was developed. Stages were identified through NHMRC Guidelines for Guidelines [26] and a time-line established. Details of the Adaptation and Finalisation stages are described as follows.

2.2. Adaptation

The adaptation stage was the largest of stages and included several steps from systematically identifying literature using a scoping review, through to the formulation of guideline recommendations.

2.2.1. Scope and purpose

The working party met with key stakeholders on two occasions through an iterative discussion process to arrive at the scope and purpose of the Comprehensive Guide to MEGA-PRESS for GABA measurement. The result of the discussions led to the identification of six key domains critical for high-quality data: Parameters, Practicalities, Data Acquisition, Confounders, Quality/Reporting, Post-processing. The working party and stakeholders agreed the following were not within scope: i) providing in-depth review of all differences between vendor-specific user interfaces, hardware, and implementations of the MEGA-PRESS sequence; ii) details regarding post-processing, modelling and quantification methods, except for those aspects with direct implications for the acquisition protocol design for example, the necessity of acquiring a water-reference signal (see 4. Discussion). Further it was agreed that the focus would be set on recommendations for measuring GABA at 3T in clinical and research populations using MEGA-PRESS, although some recommendations would translate to other metabolites, field strengths and sequences. An Open Science Framework repository (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BV6JN) [33] has been created to contain up-to-date supplementary tables a) listing the main manufacturer sequences and their key features, b) other editable metabolites.

2.2.2. Search and screening

Evidence to inform the guideline was identified through a systematically conducted scoping review. A scoping review was chosen as the methodology allows for a wider focus and the identification and mapping of available evidence in a broad topic area [34]. A search strategy was developed using terms for GABA editing (e.g. MEGA-PRESS, spectral editing, GABA) AND magnetic resonance spectroscopy (e.g. MRS, magnetic resonance spect*) AND terms specific to GABA MRS acquisition stages (e.g. gradients, shim). Three databases were searched (Ovid MEDLINE, Embase and PubMed) and reference lists of included studies were screened by the MRS expert sub-committee for any missing publications. A two-stage approach was used to screen studies for inclusion against the pre-specified inclusion criteria regarding study methods and study design (For further details of review methodology see Supplement 1). Studies were included if they used methods involving single-voxel MRS data acquired in humans, phantoms or using computer simulations. Study designs were included if they were consensus documents, systematic reviews, randomised controlled trials or methodological investigations. Studies were excluded if the methods included animals, used multi-voxel or spectroscopic imaging techniques (beyond the scope of these guidelines), or used designs that were narrative (non-evidence-based) reviews, commentaries or conference proceedings. In the first stage of screening, two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts to identify studies appropriate for full text review (AP, GO). In the second stage, full texts were screened for inclusion. Data were then extracted independently by two authors using a standardised form for each of the six pre-identified domains. Inconsistencies in screening and disagreement on exclusion/inclusion were discussed and resolved with a third reviewer (NP). The MRS sub-committee reviewed the results of the search and identified any key missing papers.

2.2.3. Results of the scoping review

The initial search retrieved 2664 studies, 21 additional publications were identified following the reference list search of included publications, the MRS-subcommittee review, and following the release of a special issue of NMR in Biomedicine. The special issue “Advanced methodology for in vivo magnetic resonance imaging” [23] contained a series of expert consensus guidelines in MRS published after the commencement of the search. Following removal of duplicates, 1460 studies were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulting in exclusion of a further 1283 records, leaving 176 records for full-text screening. Following the exclusion of 87 studies (32 due to study design, 39 due to content e.g. not MEGA-PRESS, or not relevant to 3T, and 16 for both content and design reasons), 90 publications were used to inform the guidelines (For PRISMA Flowchart see Supplement 2). Nine of the 90 publications were consensus documents, one randomized control trial, one seminal textbook describing the theory of in-vivo MR spectroscopy, one seminal paper documenting MEGA-PRESS practices, four systematic reviews, three multi-site trials, and seventy-one methodological publications. The publications used to inform each recommendation are listed in Supplement 3.

2.2.4. Evidence synthesis

The MRS sub-committee summarised evidence from the studies identified by the scoping review under the six pre-identified domains. The MRS sub-committee used an iterative process to establish where recommendations currently existed in consensus documents, and could be later considered for adoption or adaptation or where recommendations would require development. Following the ADAPTE framework for guideline adaptation [32], a recommendation is ADOPTED-when it can be lifted directly from an existing guideline or ADAPTED-when the recommendation needs to be adjusted to suit the audience or context. Where no evidence exists the recommendations are DEVELOPED DeNovo (‘from scratch’) [26]. This first scoping draft (Draft 1) included 20 recommendations under the six domains. Furthermore, the MRS sub-committee identified five areas that required recommendation development.

2.2.5. Evidence level assessment and GRADING the certainty of evidence

An NHMRC Level of Evidence was assigned to each study included in the evidence synthesis for each of the recommendations. The Level of Evidence describes the suitability of a study design to address a research question (ranging from Level 1 indicating the most robust design to Level 4 indicating the least robust design) [27]. Studies involving confounders of GABA levels were assessed using the traditional hierarchy of evidence [27] given that such research questions are best answered through systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (Level 1). For studies reporting MRS principles and acquisition parameters, the MRS sub-committee considered consensus documents the highest level of evidence (Level 1). Hence, to appraise these publications, the traditional NHMRC evidence hierarchy was adapted following the recommendations for hierarchy modification by the NHMRC [27]. When the traditional NHMRC level of evidence was used it was denoted with a superscript T e.g. Level 1T. Details of the traditional and modified evidence hierarchy are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Level of evidence modified from NHMRC (2009) [28].

| MODIFIED EVIDENCE HIERARCHY |

ORIGINAL EVIDENCE HIERARCHY |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Design | Justification | Design | Justification |

| Level 1 | Consensus Document | Traditionally a systematic review of the most appropriate study design is considered Level 1 evidence. In this case we consider expert consensus documents as Level 1 because akin to systematic reviews in other fields, these consensus documents draw on the most appropriate study designs to inform the parameters required to run a MEGA-PRESS study. All consensus documents included within this review had a panel of authors from multiple institutions across multiple countries. They also benefit from recency, with 7/9 included consensus being published in 2020/2021. | Systematic review | In line with the NHMRC recommendations [27] a systematic review of Level 2 studies will be considered Level 1. In this case meta-analysis of the studies will likely improve precision of the results. In cases where systematic reviews are of lower levels of evidence, they will be considered the same level as the studies they include, as they may increase the chance of bias [27]. |

| Seminal texts | Where core principles of physics are required to inform the guideline, seminal text of these fundamental physical properties are also considered highest level of text. | |||

| Level 2 | Systematic Review | Systematic reviews are considered Level 2 evidence as they pool together results from methodological publications which have been specifically designed to test parameters required to run a MEGA-PRESS study. However, the methodological publications typically have small sample sizes, and limitations and suffer from publication bias. | Randomised Control Trial | In order to investigate the impact of a confounder a randomized control trial would be considered the best design to address the research question. |

| Large multi-site studies | Large multi-site studies provide the most information on applying parameters in a clinical context; however, the purpose of such trials is rarely to investigate a single parameter required to run a MEGA-PRESS study. | |||

| Level 3 | Methodological publications | For the purpose of this study, methodological publications were considered as any study that had a specific aim to investigate a parameter required to run a MEGA-PRESS study. These might include studies on humans, phantoms, or simulations. These did not include animal studies. These methodological publications will often test a specific parameter required to run a MEGA-PRESS study and directly inform this guideline. However, these studies are typically performed using small samples, and are often tested on healthy subjects in non-clinical environments. | i) Comparative study with concurrent controls ii) Comparative study without concurrent controls |

Studies designs that investigate a condition compared to a control group, or situation are considered Level 3 evidence as they have the potential for bias. |

| Consensus document | Consensus documents are considered Level 3 when investigating confounders, as these research questions are better answered using a scientifically rigorous design, and therefore a consensus document is potentially biased. | |||

| Level 4 | Narrative Reviews | Narrative reviews are commonly published in the field of 1H-MRS spectroscopy but must be interpreted with caution due to the high risk of bias and personal opinion. | Case series | Case series are considered Level 4 due to being underpowered to answer these research questions, with no control for comparison. |

The modified Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [27] was then utilized to determine the degree of certainty in the body of evidence used to inform each of the recommendations. The GRADE process considers the Level of Evidence and direction of findings to determine the level of confidence that can be placed in the recommendation [27]. The modified-GRADE ranges from GRADE A where a recommendation is informed by a number of Level 1 studies providing consistent recommendations through to GRADE I where there is insufficient evidence to provide a recommendation (Table 2). The GRADE process was carried out independently by four blinded member of the development/implementation sub-committee. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Table 2.

GRADE of recommendation.

| GRADE | Criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A |

|

Body of evidence can be trusted to guide recommendation |

| B |

|

Body of evidence can be trusted to guide recommendation in most situations |

| C |

|

Body of evidence provides some support for recommendation, but care should be taken in its application |

| I |

|

Body of evidence is weak, and recommendation must be applied with caution |

Adapted from Guyatt et al. (2008) and Wright et al. (2006)

2.2.6. Decision and selection

The first draft (Draft 1) consisting of 20 recommendations was circulated to the key stakeholders prior to an in-person consensus meeting held at the 5th International GABA Symposium (19th-21st November 2019, Park City, UT, United States). The aims of the consensus meeting were: 1) to discuss key information required by those new to the field of MRS, and identify any gaps not addressed through the draft recommendations; 2) to identify and reach agreement where recommendations could be adopted or adapted from existing evidence; 3) to determine the process to develop recommendations for areas currently not supported by evidence.

As a result of the stakeholder meeting, the 20 recommendations were revised and augmented to 26 recommendations. Agreement was reached that 12 recommendations were suitable for direct adoption, nine for adaptation, and five required development (note: four of these five were later adapted from recommendations in newly released consensus documents). It was agreed that the process for development would be led by the MRS sub-committee. The MRS sub-committee would use and customise evidence from other fields or sequences for GABA MEGA-PRESS. Discussion regarding the key information required for those new to the field was agreed upon.

These decisions were then forwarded to the development/implementation sub-committee. This sub-committee wrote recommendations in easily understandable language suitable for those new to the field of MRS. The revised draft was then circulated back to the stakeholders and a finalised draft (Draft 2) was prepared to be circulated for review by an external expert panel.

2.3. Finalisation

The finalisation stage included; external expert review, production of this peer review publication, one-page infographic and extended guideline, and agreeing upon the implementation and dissemination plan and schedule for review and update [32].

2.3.1. External review

The finalised draft (Draft 2) was sent for agreement and review by a panel of experts using a modified-Delphi process. The modified-Delphi process is a group consensus strategy, designed to transform opinions into group consensus using an iterative multi-stage process [35,36]. The expert panel was established through invitation by the MRS sub-committee. Experts were identified based on their contribution to recent MRS consensus documents, and their contribution to the field of MRS. The panel consisted of 21 expert MRS researchers from 15 universities in eight different countries. In Round 1, experts rated a) their agreement with the content of the recommendation, and b) the suitability of the recommendation for use in a beginner's guide. Ratings were on a Likert scale of −5 to +5 (where −5 to −1 indicated disagreement, 0 represented a neutral opinion, and 1 to 5 indicated agreement). Experts were also given the opportunity to comment on each of the recommendations and submit suggestions for modifications. The results from Round 1 and 2 expert panel agreement were analysed using percentages.

Recommendations were classified as having ‘expert panel endorsement’ and accepted into the final guideline where at least 80% of the expert panel had agreed to the recommendation. In cases where recommendations did not reach the 80% threshold, they were revised, taking into account the written feedback from the expert panel. These revised recommendations were then re-sent to the expert panel for a second rating (Round 2). The Round 2 expert panel consisted of 20 of the original experts, as one expert was unavailable to review the revised recommendations. Any recommendation not achieving agreement of at least 80% of the expert panel in Round 2 was not given the ‘expert panel endorsement’ label. In these instances, evidence was reviewed by the working party, and the significance of removing the recommendation from the guideline was deliberated until a final verdict on the recommendation was reached.

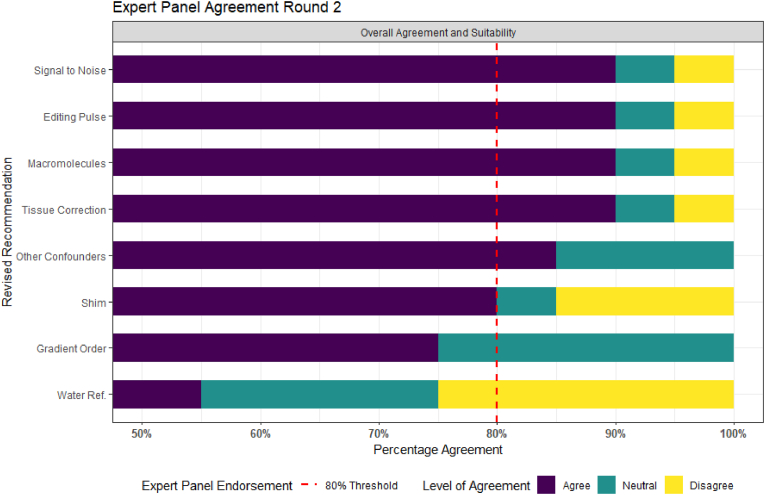

2.3.2. Recommendation development

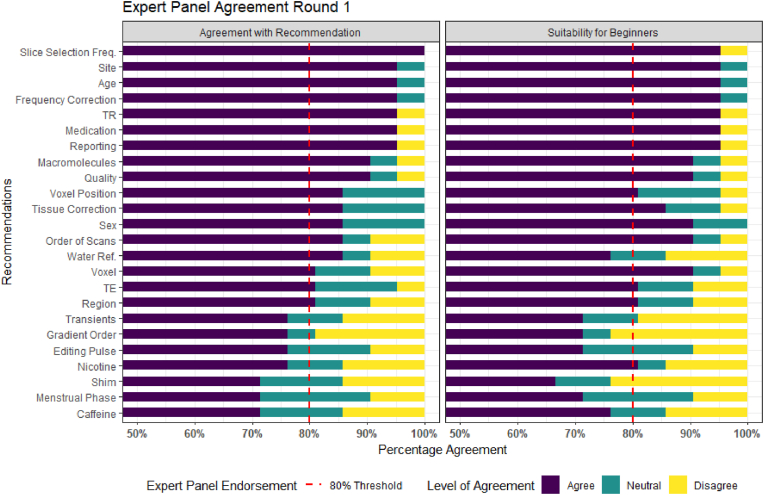

The finalised Comprehensive Guide to MEGA-PRESS for GABA Measurement consists of 23 recommendations across the six key domains. Nineteen of the 26 recommendations sent for expert panel review (Draft 2) received expert panel endorsement (over 80% agreement) in Round 1 (Fig. 2). Sixteen of these were immediately accepted into the guideline. Three of the nineteen required further refinement (1 due to new evidence being published, one due to not being deemed suitable for those new to the use of MEGA-PRESS by the expert panel, one due to being deemed too long by the expert panel). Following expert feedback from Round 1, the recommendations were consolidated and re-grouped from 26 to 23 recommendations. Overall, eight recommendations were revised and submitted to the expert panel for Round 2 assessment. Following Round 2, a further six recommendations received expert panel endorsement and were accepted into the guideline (Fig. 3). Two recommendations did not receive expert endorsement (‘gradient order’ - 75% and ‘water reference’ - 55%). In these cases, the MRS sub-committee revisited the evidence for these recommendations and debated the inclusion of these recommendations in the guideline. In both cases the result of the debate was to include the recommendation, without expert panel endorsement, with the addition of further explanatory notes in the consideration section of the extended document.

Fig. 2.

Results from Round 1 of the Expert panel review, results displayed from highest to the lowest level of agreement and scaled from 50% to 100% agreement.

Fig. 3.

Results from Round 2 of the Expert panel review, results displayed from highest to the lowest level of agreement and scaled from 50% to 100% agreement.

2.3.3. Final guideline outputs

The three outputs from this work include.

-

1)

A Comprehensive Guide to MEGA-PRESS for GABA measurement (Full guideline)

The full guideline (Supplement 4) is a detailed stylised document providing background information on the subject of each recommendation, updates to the guide will be made available on the Open Science Framework repository [33]. The full-length guideline is recommended for consultation when using MEGA-PRESS for the first time, particularly during the study protocol design phase. Each final recommendation included in the guideline is the result of the evidence synthesis and the expert panel feedback. Therefore this guideline consists of the full evidence summary that informed the recommendation, and includes the key considerations added by the expert panel that resulted in the final recommendation.

-

2)

The peer reviewed publication (This manuscript)

This peer reviewed publication first outlines the rigor of the methodological process of recommendation development and then provides a summary of the recommendations. This manuscript provides GRADE of evidence, percentage of expert panel agreement and a shortened summary of the evidence synthesis and expert panel feedback that informed the recommendation. This manuscript can be used instead of the full-length guideline when a brief overview of parameters that determine data quality is sufficient.

-

3)

One-page infographic summary

The infographic (Supplement 5) provides a quick visual reference guide, summarizes the key messages of the Comprehensive Guide and provides a memory aid to users who have previously read the full guideline. Its purpose is to improve the translation of the guideline into standard practice.

2.3.4. Dissemination, implementation and review

The working party designed the dissemination and implementation plan. Dissemination will occur at key annual meetings and conferences where target markets, such as junior researchers, applications-oriented scientists, and educators will be in attendance. This includes the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM), Society for MR Radiographers & Technologists (SMRT) and Organization for Human Brain Mapping (OHBM). In addition, the guideline will be presented in workshops focused on GABA-MRS and educationals such as the International Symposium on GABA and Advanced MRS and EDITINGSCHOOL, where attendees have a specific interest in GABA MRS.

Pilot implementation will commence at all of the working parties’ collaborative sites (over 25 sites worldwide), where the guideline will be integrated in current operating procedures, and the infographic will be distributed. In addition, members of the guideline working party will integrate it into their supervision and teaching procedures to students (graduate and undergraduate), residents and researchers. The guideline will be reviewed for currency by the working party in 2026 and updated should further high-quality evidence provide recommendations differing to those presented in this guideline.

3. Results

The final guideline consisted of 23 recommendations, under six domains essential for GABA MRS acquisition; Parameters, Practicalities, Data acquisition, Confounders, Quality/reporting, Post-processing. Overall 78.3% of recommendations were formed from high quality evidence (Level A or B) and 91.3% received agreement from over 80% of the expert panel (Table 3). In total, 12 (52.2%) recommendations were ADOPTED directly from existing recommendations without adjustments, 10 (43.3%) were ADAPTED with adjustments to make the recommendation specific to GABA or MEGA-PRESS and 1 (4.3%) was DEVELOPED De novo ‘from scratch’ using best available evidence.

Table 3.

Summary of recommendations.

| Evidence GRADE | Experts: R1 (%) Agreement | Experts: R2 (%) Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | SNR | - Number of Transients - Voxel Size |

A | 76.2 | 90 |

| 81 | |||||

| TR | A | 95.2 | – | ||

| TE | A | 81 | – | ||

| Water Reference | A | 85.7 | 55 | ||

| Slice selection for water ref | A | 100 | – | ||

| Gradient | I | 76.2 | 75 | ||

| Editing Pulse | A | 76.2 | 90 | ||

| Practicalities | Voxel Position | A | 85.7 | – | |

| Shimming | A | 71.5 | 80 | ||

| Order of Scans | A | 85.7 | – | ||

| Confounders | Scanner Site | B | 95.2 | – | |

| Macromolecules | A | 90.5 | 100 | ||

| Region | C | 81 | – | ||

| Tissue Composition | A | 85.7 | 90 | ||

| Age | A | 95.2 | – | ||

| Sex | C | 85.7 | – | ||

| Medications | B | 95.2 | – | ||

| Other | Caffeine | I | 71.4 | 85 | |

| Nicotine | 76.2 | ||||

| Menstrual Phase | 71.4 | ||||

| Data Acquisition | Quality Assessment | A | 90.5 | – | |

| Export | I | 90.5 | – | ||

| Quality and Reporting | Quality Metrics | A | 90.5 | – | |

| Reporting | A | 95.2 | |||

| Post-Processing | Frequency and Phase Correction | A | 95.2 | ||

3.1. Parameters

3.1.1. Signal-to-noise ratio considerations (number of transients and voxel volume)

ADAPT: Start with at least 192 transients (i.e. 96 Edit-ON + 96 Edit-OFF) and a voxel volume of 27 ml (e.g 3 × 3 × 3 cm3) to quantify GABA when scanning a favourable brain region.

Note: Consider increasing the total number of transients when scanning smaller or more challenging brain regions (see 3.3.3 Region).

Evidence GRADE A. Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement number of transients 76.2%, voxel size 81%, Round 2 Expert Panel Agreement 90%

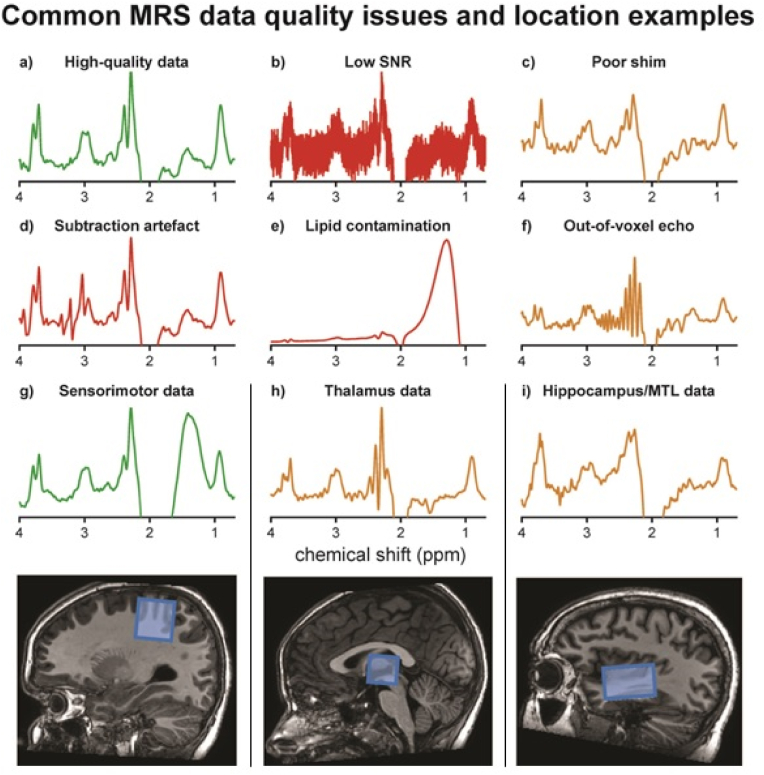

There were eight studies (Level 1 to Level 4) [19,[37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]] with recommendation about the number of transients, and seven studies (Level 1 to Level 4) [19,37,38,[44], [45], [46], [47]] with recommendation about voxel volume. The studies recommended using a range of transients from 126 [41] to 320 [37,38] transients, with the majority recommending a minimum of 192 transients when using a voxel volume of, e.g., 3 × 3 × 3 cm3. A further two studies (Level 1) [6,48] highlight the importance of reporting the number of transients used and whether they refer to the total number of transients or separate (as Edit-ON and Edit-OFF). Failure to achieve adequate signal to noise has a significant effect on quality of the spectra as demonstrated in Fig. 4. Round 1 agreement for this recommendation was 76.2% for number of transients and 81% for voxel size. Two key considerations were made: first, experts recommended combining the two separate recommendations to highlight the interdependence of the number of transients and voxel size. Second, the number of transients are best selected in multiples of 16 to allow for full phase cycles to be included. Round 2 agreement increased to 90%. Therefore, the revised recommendation was accepted.

Fig. 4.

Sample MEGA-PRESS data, and common quality issues that can occur, green demonstrating higher quality data, orange medium and red low. a) High-quality data with sufficient SNR, narrow linewidths, a well-defined edited signal at 3 ppm, and no substantial artefacts; b) very high noise levels due to low number of transients or small voxel volume; c) poor shim resulting in poor spectral resolution and lower SNR; d) severe subtraction artefacts due to scanner frequency drift; d) lipid contamination due to participant motion or voxel positioning too close to the skull; e) out-of-voxel echo (“ghost signal”); g) sensorimotor data and voxel location, usually a region that is easy to shim, but risks lipid contamination as demonstrated here; h) thalamus data and voxel location usually lower SNR, linewidths often greater due to iron deposition in deep regions; i) hippocampus/medial-temporal lobe data and voxel location, a region that is difficult to shim and prone to artefacts.

3.1.2. Repetition time (TR)

ADOPT: Use a TR of around 2000 ms at 3T.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 95.2%

There were five studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [37,38,[49], [50], [51]] that provided recommendations on TR. The studies all concur that a TR of ∼2000 ms is suitable for the measurement of GABA with edited MRS at 3T, given its longitudinal relaxation time of approximately 1300 ms [52]. Round 1 agreement was 95.2%. Therefore, this recommendation was adopted.

3.1.3. Echo time (TE)

ADOPT: TE should be 68 ms (GABA+); 80 ms (macromolecule-suppressed GABA).

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 81%

There were ten studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [19,20,22,29,37,38,50,51,53,54] that provided recommendation on TE. The consensus across studies was to keep TE as close to 68 ms as possible when estimating GABA+, and 80 ms for macromolecule-suppressed measurements. Round 1 agreement was 81%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.1.4. Water reference

ADAPT: Water reference scans (required for eddy-current correction and water-scaled quantification): acquire two water reference scans for each volume of interest: one using the same parameters as MEGA-PRESS, but deactivated water suppression for eddy-current correction, and one short-TE PRESS acquisition (TE ∼30 ms) for quantification.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 85.7%, Round 2 Expert Panel Agreement 55%

There were seven studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [19,24,47,51,[55], [56], [57]] that provided recommendation on water reference scans. There was consensus across studies recommending that water reference scans are acquired from the same volume of interest using the same parameters and gradients in order to facilitate eddy-current correction. Round 1 agreement was 85.7%, but only 70% felt the recommendation was suitable for a beginner's guide. Experts reasoned that those new to MRS might not be aware that using long-TE water data for quantification purposes may introduce T2-weighting, which inadvertently has implications for quantification [58]. In line with the feedback and the publication of a new consensus document [57], the recommendation was revised to recommend acquiring a separate short-TE PRESS water reference scan to be used for quantification. However, Round 2 agreement reduced to 55% due to several experts (n = 8/20, 40%) not considering a short-TE scan necessary for quantification. The inclusion of this guideline was discussed by the working party. The decision was made to retain the revised recommendation due to it reflecting the most up-to-date recommendation in the literature. It was decided to further develop the preface and consideration section for educational purposes to help the translation of this new recommendation, given the feedback from the experts. Information on GABA-specific water-based quantification can be found in Harris et al. [59] and Oeltzschner et al. [56].

3.1.5. Slice-selection centre frequency of water reference scan

ADOPT: Set the water reference to be acquired from the same volume as the GABA signal.

Evidence GRADE B; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 100%

There were three studies (Level 2 to Level 3) [37,38,50] that provided recommendations on slice-selection centre frequency of the water reference scan. The consensus across studies was that the frequency should be set to 0 ppm offset, i.e. localizing the 4.7 ppm water signal. Round 1 agreement was 100%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.1.6. Order of slice-selective gradients

ADAPT: When artefacts appear in pilot data, consider changing the order of the slice-selective gradients for each volume of interest.

Evidence GRADE I; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 76.2%; Round 2 Expert Panel Agreement 75%

There was one paper (Level 3) [60] that provided recommendations on the order of slice-selective gradients. The paper highlighted how changing the order of gradients can remove artefacts from data. Round 1 agreement was 76.2% due the recommendations suggesting that trial acquisitions with different orders should be conducted. In line with feedback from expert consensus, the recommendation was revised to suggest this as a troubleshooting option only when artefacts are consistently present in data. Round 2 agreement reduced to 75% due to concerns that those new to using MEGA-PRESS would not know which artefacts could be helped by changing gradient order (n = 3/20, 15%) and that some systems do not allow for simple adjustment of gradient order. The decision to maintain the recommendation was made by the MRS sub-committee who felt this troubleshooting advice might be helpful to those new to using MEGA-PRESS, with the addition of Fig. 4 which demonstrates some commonly observed artefacts. This recommendation therefore was included, but not given expert approval.

3.1.7. Editing pulse specifications

ADOPT: Editing pulses can be applied as follows (Table 4).

Table 4.

Editing pulse specifications.

| GABA+ | Macromolecule-suppressed | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (ppm) | ||

| Edit-ON | 1.9 ppm | 1.9 ppm |

| Edit-OFF | 7.46 ppm | 1.5 ppm |

| Bandwidth | 60 Hz | Usually 80 Hz (60 Hz on some implementations) |

| Spacing | 0.5 TE apart (this parameter is usually not accessible to the user) | |

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 76.2%; Round 2 Expert Panel Agreement 90%

There were nine studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [[19], [20], [21], [22],37,38,50,61,62] that provided recommendation on editing pulse parameters. Recommendations were dependent on whether GABA + or macromolecule-suppressed GABA was being acquired (see Supplement 4 full-length guideline for explanation). Round 1 agreement was 76.2%, the recommendation was therefore revised. Key points from the expert panel were that some sequence implementations do not allow for the adjustment of these parameters. The panel had many suggestions of variations that they use when applying editing pulses (n = 8/21, 38.1%) which highlight the methodological heterogeneity even among experts in the MRS field. The revised recommendation removed recommendations for pulse duration and highlighted that editing pulses could be applied using these parameters as a starting point for those new to using MEGA-PRESS. Round 2 expert panel agreement was 90%. Therefore, this revised recommendation was accepted.

3.2. Practicalities

3.2.1. Voxel position

ADAPT: Use automated voxel positioning tools where available. If manually positioning the voxel, use a screenshot and clear instructions regarding positioning relative to anatomical landmarks and degree of rotation.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 85.7%

There were five studies (Level 1 to Level 4) [24,46,[63], [64], [65]] that provided recommendations on positioning of the voxel. The studies recommended use of an automated voxel positioning tool. Although the expert panel agreed with this recommendation, 28.6% of experts highlighted that fully automated voxel positioning is not currently available as standard. Round 1 agreement was 85.7%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.2.2. Shimming

ADAPT: A beginner should use a readily available automated field-map-based shim and minimize the use of manual adjustments.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 71.5%; Round 2 Expert Panel Agreement 80%

There were eight studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [24,41,51,[66], [67], [68], [69], [70]] that provided recommendation on shimming to maximize the homogeneity of the static magnetic field (B0). The studies demonstrated that projection-based shim optimisation or second-order pencil beam methods could provide narrower linewidths than the default 3D field map-based methods. These specific techniques may not be readily available on all systems, therefore the expert panel recommends that any readily-available automated field map-based methods are used with minimal manual adjustments where possible (9/21, 43%). Round 1 agreement was 71.5%, subsequent adjustments were therefore made to highlight that linewidths are calculated differently by different vendors (see considerations in extended document). Despite evidence suggesting projection-based shim optimisation might achieve narrower linewidths, the recommendation states the beginner should use readily available field-map based shim methods. Round 2 expert agreement was 80%. Therefore, the revised recommendation was accepted.

3.2.3. Order of scans and field drift

ADOPT: Where possible, MRS should be conducted prior to gradient-heavy acquisitions or in small blocks of 2–5 min with frequency adjustments between adjustment blocks. Consider using real-time frequency correction if available.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 85.7%

There were seven studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [[22], [23], [24],37,43,54,71] that provided recommendation on the order of scans and the effect it has on field drift. The studies highlighted the negative impact gradient-heavy scanning (e.g. diffusion tensor imaging) has on frequency drift during subsequent MRS scans. Previous recommendations were to avoid scanning after gradient-heavy acquisitions, however owing to this not being practical due to scan scheduling problems, a recent consensus document made a new proposal. The recommendation was to acquire MRS data in small blocks with frequency adjustment after each block whilst monitoring the residual water signal on the inline display during the scan acquisition in order to detect drift. Round 1 agreement was 85.7%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.3. Confounders

3.3.1. Scanner site and vendor

ADOPT: In multi-site studies, standardised protocols should be used, and the degree of systematic differences between site/scanner should be reported.

Evidence GRADE B; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 95.2%

There were three multi-site studies (Level 2) [37,38,62] that provided recommendations on managing scanner site and different vendors as a confounder of GABA. The studies reported a coefficient of variation across all data sets of around 12% for GABA+/Cr and 17% for water-scaled GABA+. Macromolecule-suppressed MEGA-PRESS had larger CVs of 28%–29% for both GABA/Cr and water-scaled GABA [37,38]. Round 1 expert panel agreement was 95.2%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.3.2. Macromolecules

ADAPT: A beginner should use conventional MEGA-PRESS reporting GABA+. Macromolecule contamination should be acknowledged as a limitation, and consideration paid to whether macromolecules could be responsible for between-group differences.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 90.5%; Round 2 Expert Panel Agreement 100%

There were twelve studies (ranging from Level 1 to Level 3) [19,22,23,53,[72], [73], [74], [75], [76],54,21] that provided recommendation on macromolecule contamination as a confounder of GABA. Contrary to the original consensus document for MEGA-PRESS (Level 1) [19], the latest consensus documents recommend the use of macromolecule-suppressed editing where possible (Level 1) [23,54]. However, both consensus documents acknowledge this approach has a number of limitations including its susceptibility to frequency drift. The expert panel agreed that a macromolecule-suppressed study is more difficult to control and run as a beginner and therefore endorsed the recommendation that a beginner should acquire GABA + data. Both consensus documents agree that in cases where GABA+ is acquired, results must be reported as GABA + macromolecules, with macromolecule contaminations explicitly acknowledged as a limitation. Round 1 expert panel agreement was 90.5%. This recommendation was revised following publication of a new consensus document and therefore sent out for Round 2 grading despite achieving over 80% expert panel agreement on Round 1. Round 2 agreement was 100%. Therefore, the revised recommendation was accepted.

3.3.3. Region

ADAPT: Select brain regions relevant to the research question, however, acknowledge that brain regions have differing reliability with respect to data acquisition.

Evidence GRADE C; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 81%

There were fourteen studies (Level 1T to Level 4 T) [40,46,70,[77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87]] that provided recommendation on brain region as a confounder of GABA levels. The studies demonstrated that GABA levels appear to be region-specific rather than reflective of a global GABAergic tone as once proposed [87]. Therefore, it is important to consider the suitability of the brain region for 1H-MRS acquisition and recognize that different brain regions have different reliability with respect to signal-to-noise ratio and the likelihood of artefacts. Round 1 agreement was 81%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.3.4. Tissue composition

ADAPT: Water-scaled quantification methods should consider the impact of partial volume effects on GABA estimation.

Note: Segmented structural images should be used along with a tissue-correction method to account for grey matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid composition of the voxel. Grey-matter only correction should be avoided.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 85.7%; Round 2 Expert Panel Agreement 90%

There were nine studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [19,23,58,59,83,85,[88], [89], [90]] that provided recommendation on tissue composition as a confounder of GABA estimation. The studies agreed that GABA levels were higher in grey matter than white matter, and therefore needed to be accounted for when quantifying GABA. The additional considerations from the expert panel were that tissue composition should be considered as a covariate in order to clarify whether between-group differences were being driven by GABA levels rather than tissue composition (n = 3/21, 14.3%). Round 1 agreement was 85.7%. However, the original recommendation included a significant number of caveats. Therefore, to improve clarity the recommendation was revised, where the caveats were removed from the recommendation and placed in the considerations section of the full document. Round 2 agreement was 90%. Therefore the revised recommendation was accepted.

3.3.5. Age

ADOPT: Age is likely to affect GABA levels, therefore age should be accounted for in study design or statistical analysis.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 95.2%

There were seven studies (Level 1T to Level 3T) [85,86,[91], [92], [93], [94], [95]] that provided recommendations on age as a confounder of GABA levels. Six studies suggest that GABA + decreases with age in adulthood. Conversely, one study found no relationship between MM-supressed GABA and age, and an age-dependent increase in GABA+ [91]. The recent meta-analysis [95] describes an early period of increase in frontal GABA levels, which stabilized throughout adulthood, and then decreased with aging. Round 1 agreement was 95.2%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.3.6. Sex

ADOPT: Sex is likely to impact on GABA levels, therefore sex should be accounted for in study design or statistical analysis.

Evidence GRADE C; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 85.7.

There were four studies (Level 3T to Level 4T) [86,91,96,97] that provided recommendation on sex as a confounder for GABA levels. The variation in outcome across the studies suggest that differences in GABA levels between males and females may be region-specific. Round 1 agreement was 85.7%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.3.7. Medications

ADAPT: Medications may impact GABA levels, as minimum best practice all medications should be recorded.

Note: Consider excluding participants taking medications likely to affect the GABAergic system.

Evidence GRADE B; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 95.2%

There were eight studies (Level 1T to Level 4T) [87,[98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104]] that provided recommendations on medications that may confound GABA. The studies reported that medications that alter GABA concentration directly and those that affect GABA receptor agonists and antagonists may both influence brain GABA levels. Round 1 agreement was 95.2%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.3.8. Other potential confounders: nicotine, caffeine, phase of menstrual cycle

ADAPT: Potential confounders such as caffeine and nicotine intake and phase of menstrual cycle may affect GABA levels, as minimum best practice potential confounders should be recorded.

Evidence GRADE I; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement Caffeine 71.4%, Nicotine 76.2%, Phase of Menstrual Cycle 71.4%, Round 2 Expert Panel Agreement 85%

There were six studies (Level 3 T to 4T) [77,[105], [106], [107], [108], [109]] that provided recommendation on other potential confounders of GABA levels which included caffeine, nicotine, and phase of menstrual cycle. The studies were inconclusive to the degree of effect these potential confounders may have on GABA levels. Round 1 agreement was caffeine 71.4%, nicotine 76.2%, phase of menstrual cycle 71.4%. Expert panel feedback was that there was not sufficient high-quality evidence confirming these factors as confounders of GABA levels, and therefore the expert panel did not feel it was essential to control for all in study design. The recommendation was adjusted to reflect this. Round 2 agreement was 85%. Therefore, the revised recommendation was accepted.

3.4. Data acquisition

3.4.1. Quality assessment during the scan

ADOPT: It is recommended to monitor the quality of the acquisition using the inline data display at time of scanning.

Note: Scans should be cancelled, and voxel position adjusted if evidence of weak water suppression, strong lipid contamination or other artefacts.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 90.5%

There were two studies (Level 1) [23,24] that provided recommendations on quality assessment during the scan. Both recommended that the MR operator should evaluate and monitor water suppression efficiency, spectral linewidth and signal-to-noise ratio at the beginning and during the MRS acquisition. Should artefacts be seen during the scan, stopping the scan and adjusting the voxel position is likely to help correct for weak water suppression, lipid contamination or other artefacts. Round 1 expert panel agreement was 90.5%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.4.2. Data export

DEVELOP: Export data in a format that saves individual transients to allow adequate post-processing.

Evidence GRADE I; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 90.5%

There were no studies discussing file format export for MEGA-PRESS acquisitions. The recommendation was therefore developed based on a consensus document that made recommendations on the file format to export for 1H-MRS studies which also can be applied to MEGA-PRESS acquisitions [57]. Round 1 expert panel agreement was 90.5%. Therefore, the developed recommendation was accepted.

3.5. Quality and reporting

3.5.1. Quality metrics

ADOPT: Report spectral quality in terms of the signal-to-noise ratio, linewidth, water suppression efficiency, fit quality, and the presence of unwanted spectral features.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel agreement 90.5%

There were seven studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [19,24,46,51,69,110,111] that provided recommendations on which variables should be used to assess data quality. The studies agree that spectral quality should be assessed using a number of aspects including signal-to-noise ratio, linewidth, water suppression efficiency, modelling quality, and presence of unwanted spectral features. Round 1 agreement was 90.5%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.5.2. Reporting

ADOPT: When reporting results use one of these two checklists (MRS in MRS, Lin et al. 2020 or MRS-Q, Peek et al. 2020) using the appropriate terminology (Kreis et al. 2020). Include detailed reporting of hardware, MEGA-PRESS-specific acquisition parameters, quantification details, quality metrics, and analysis methods.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 95.2%

There were three studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [6,48,50] that provided recommendations on reporting in MEGA-PRESS GABA studies. Two studies provided checklists that could be utilized to improve reporting in these studies. The studies agree that representative example spectra should be visualised for each region of interest to allow the reader to assess the quality of the data. While comparisons between pathological condition and control can be plotted, it is noted that spectral differences may not be clearly evident on plotted spectra due to the typically small effect sizes observed (see Supplement 4 full-length guideline for further information). Round 1 agreement was 95.2%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

3.6. Post-processing

3.6.1. Frequency-and-phase correction (post-processing)

ADOPT: Frequency-and-phase alignment of individual transients should be performed during post-processing.

Evidence GRADE A; Round 1 Expert Panel Agreement 95.2%

There were ten studies (Level 1 to Level 3) [23,43,57,[112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118]] that provided recommendation on frequency-and-phase correction. The studies found that using frequency-and-phase correction was able to significantly improve editing efficiency. Round 1 agreement was 95.2%. Therefore, this recommendation was accepted.

4. Discussion

The Comprehensive Guide to MEGA-PRESS for GABA Measurement presented in this manuscript, was developed following a translational framework to produce robust, user-friendly guidelines for those new to using MEGA-PRESS. The key strengths of this approach were conducting a systematically delivered scoping review to inform the evidence synthesis and the involvement of multiple stakeholders with diverse experience and expertise. Further, we performed blinded GRADEing of the quality of evidence for each recommendation, and then finally incorporated expert peer review through the modified-Delphi process. The result was a guideline with 23 recommendations; 17 (73.9%) of these recommendations had a high GRADE of evidence and high expert panel agreement, 1 (4.4%) had a high GRADE of evidence but low expert panel agreement, 4 (17.4%) had a low GRADE of evidence and high expert panel agreement, and 1 (4.4%) had a low GRADE of evidence and low expert panel agreement. Reasons for the differences between GRADE of evidence and the degree of expert panel agreement plus the decisions to retain the recommendations that did not gain expert panel approval are discussed below.

Both 3.1 ‘Parameters’ and 3.2 ‘Practicalities’ sections contain recommendations with a high GRADE of evidence and a high percentage of expert panel agreement, with the exception of just two recommendations (Table 3). This high level of evidence supported by the expert panel encourages confidence in our recommendations, as expert evaluation reflects practice in experienced MRS groups worldwide. The two recommendations in the guideline that were not sufficiently endorsed by the experts were both in the 3.2 ‘Practicalities’ section; Order of slice-selective gradients (Evidence GRADE I, Experts: 75% agreement, 25% neutral) and Water reference scans for eddy current correction and water-scaled quantification (Evidence GRADE A, Experts 55% agreement, 20% neutral, 25% disagreement). This lower level of expert panel agreement suggests that these recommendations are less reflective of current standard practice. The MRS sub-committee saw an opportunity to encourage the translation of evidence to practice and decided to keep the recommendations in the guideline without expert panel endorsement but with further discussion: Firstly, while experts were concerned that Order of slice selective gradients is not applicable to all systems, the MRS sub-committee found it a valuable troubleshooting option worth adopting as regular practice on systems where it is available. Secondly, Water reference scans for eddy-current correction and quantification failed to gain expert panel endorsement following the addition of a separate short-TE scan for quantification, although this practice is recommended in the latest consensus document [57]. The MRS sub-committee maintained this recommendation to further facilitate the implementation of this new recommendation into practice.

It should be noted that acquisition parameters such as the number of transients, the voxel size, repetition and echo time all influence the signal-to-noise ratio of an acquisition. The recommendations in this guide are valid as a set, i.e. the recommendation to acquire 192 transients is valid for a 27-ml voxel with TR/TE = 2000/68 ms. For novices, it is important to recognize that it is vastly more challenging to acquire high-quality data in some brain regions than in others [51]. Regions close to tissue-air transitions (e.g. frontal cortex, hippocampus) may feature sudden spatial changes in magnetic susceptibility and are therefore difficult to shim and more likely to exhibit unwanted signal artefacts. Since RF coil sensitivity profiles are not homogenous throughout the brain, some regions may also experience lower signal-to-noise ratio than others (e.g. deep brain regions vs. cortex). It is beyond the scope of this guide to provide detailed tailored MRS instructions for every brain region of interest to researchers, and the parameter recommendations should be understood as a starting point from which further optimisation and experimentation can be performed.

The 3.3 ‘Confounders’ section contained recommendations with generally lower levels of evidence but achieved high expert panel agreement. Firstly, five of the eight recommendations in this domain were assessed using a traditional hierarchy of evidence, where Level 1 evidence represents a systematic literature review of randomised controlled trials, a study design that has not been frequently adopted in the field of MRS to date. Secondly, many of the recommendations in this section reflect principles and practices historically adopted from expert opinion and practical experience rather than from clear and systematic evidence collection. This explains the high level of expert agreement, but also shows further high quality research is required to establish the degree of confounding these factors present.

The 3.4 ‘Data Acquisition’, 3.5 ‘Quality and Reporting’ and 3.6 ‘Post-processing’ sections generally had high levels of evidence and high expert panel agreement. The high levels of evidence adapted from consensus documents and high expert panel agreement reflect that areas included in these domains are topical, relevant and are considered important in the acquisition of GABA using MEGA-PRESS. The one recommendation that had no evidence (Level I), and therefore required active development instead of adoption or adaption was File export. Previous consensus documents may not have included this explicit recommendation as it might be considered ‘assumed knowledge’, but the MRS-subcommittee and stakeholders valued its inclusion given the intended audience. This is especially relevant since failure to save the correct file type at time of scanning prevents appropriate post-processing and compromises data quality considerably; an easily-avoidable mistake that has been commonly observed by the MRS sub-committee. It should be noted that there are many possible definitions for the quality metrics (e.g. SNR, linewidth). While the MRS sub-committee encourages the use of the definitions outlined in consensus papers [25,51,57], there is no formal recommendation. Instead, it is imperative to report details on the calculation of quality metrics, e.g. which peak was used to determine signal and linewidth, and which frequency range of the spectrum was used to calculate the noise.

The results of the evidence synthesis did not always provide recommendations suitable for a those new to using MEGA-PRESS. In two instances (Shimming and Macromolecules), the MRS sub-committee and expert panel agreed that a beginner would likely achieve a better result using a different approach to that recommended in the most recent consensus documents [54,66]. An example was shimming: a recent consensus document [66] recommends use of a tool that is not readily available on all systems, has limited technical support, requires approved distribution from its developers, and is more technically challenging to operate than system based shim methods (FASTMAP). Whilst proof-of-concept studies [30,69,119] have demonstrated that narrower linewidths can be achieved using this approach compared to readily available automated field map-based methods, it requires specific expertise to be set up and used. Therefore, the MRS sub-committee and expert panel recommend that a beginner use a readily-available automated field-map-based shim method. Doing so is well-established in the field and should produce sufficient B0 homogeneity to generate high-quality spectra [19]. In summary, while this recommendation is not consistent with the recent consensus document, it is directly aligned with our aim of enabling a beginner to produce high-quality MEGA-PRESS spectra for the reliable quantification of GABA.

The second recommendation adapted for the beginner in our guideline was Macromolecules and how they should be handled. Feedback from 90.5% (20/21) experts was that beginners should choose sequence parameters to acquire GABA plus macromolecule (GABA+) data, despite the latest consensus document recommending the acquisition of macromolecule-suppressed data. This is supported by a previous consensus document [19] and methodological publications [19,37,53] that all agree that symmetric macromolecule suppression is an order of magnitude more susceptible to frequency drift and that other methods of macromolecule signal removal all have substantial technical and practical limitations [19,37,53]. The MRS sub-committee reviewed the evidence once more, and decided that despite our recommendation differing from the latest consensus document [54], acquiring GABA + currently offers the most robust, reliable and widely used method to measure GABA levels for a beginner user. Further the likelihood of failure acquiring GABA+ is substantially lower than if they were to use the delicate macromolecule suppression. Therefore, the recommendation to acquire GABA + data and acknowledge the macromolecule contamination as a limitation (or discuss as a potential source of observed effects) was deemed most suitable for inclusion in the Comprehensive Guide.

Limitations

In the process of peer review, several aspects of the recommendations were contested. In particular, it was suggested that some recommendations are unnecessary or not specific to MEGA-PRESS (specifically: voxel volume; number of transients; echo time; slice-selection frequency; gradient order; voxel position; order of scans; site; region; tissue composition; age; sex; medication; reporting; frequency/phase correction) or that they are not useful recommendations. It was further suggested that the guidelines merely replicate previous expert consensus, that several recommendations prioritize ease of implementation over a theoretically achievable best result, and that the guide should also contain recommendations for metabolites other than GABA. We acknowledge and respect these suggestions since they clearly reflect the highly divergent experiences and practices in the field of MRS. However, each recommendation is the result of a widely recognized standardized process for guideline synthesis and has received strong expert panel endorsement. We further maintain that a complete guide to a method needs to incorporate all recommendations that are vital for its successful application, even if they may not be specific to MEGA-PRESS in particular. We therefore chose to report the objections transparently in the Discussion section rather than by modifying the expert-endorsed guidelines themselves.

The scope of the Comprehensive Guide was to largely focus on study design and data acquisition. We note that many other sequences for J-difference editing exist (MEGA-sLASER, MEGA-SPECIAL [29], HERMES [30]). Many recommendations made in this guide are likely to apply to these adapted sequences, while others may require modification. This guide focused exclusively on MEGA-PRESS because, at the time of writing, it is available as a product or WIP sequence for the three major vendors (See OSF repository [33]), whereas other sequences require specific C2P research agreements. Their ‘market share’ is also comparably low, and consequently, comparably little evidence to draw recommendations from exists. We also note that MEGA editing is used for many other metabolites of interest, and we have compiled a list of experimental parameters (See OSF repository [33]) that may be used to translate the recommendations in this guide to enable the detection of glutathione, lactate, etc. However, information regarding other metabolites has not synthesized using the Delphi process, i.e., not been collected through a scoping literature review and not been subjected to expert panel assessment, and should therefore be considered with caution. Many aspects of this guide (tissue correction; macromolecules, confounders, etc.) that apply to GABA may not be transferable to other metabolites at all.

We considered it to be beyond the scope to discuss further details of post-processing (beyond frequency-and-phase correction and the file format export it requires), modelling, or quantification of MEGA-PRESS data. We therefore direct the reader to comprehensive efforts on best practices in MEGA-PRESS [19] and two recent consensus papers on pre-processing, modelling and quantification [57] and spectral editing in general [23]. Further, the beginner is advised to liaise with representatives from their vendor and sequence developers with regard to system-specific functions that may or may not be available, as highlighted throughout this Comprehensive Guide. Finally, the MRSHub (https://www.mrshub.org) provides an online resource hosting processing and analysis software, normative example data, and a discussion forum frequented by beginners and experts alike where questions about study design and protocol can be posed.

In conclusion, this Comprehensive Guide combines a robust evidence synthesis on the measurement of GABA levels with edited MRS and expert panel review. The result is an evidence-based, peer-reviewed guideline for those new to using MEGA-PRESS including higher degree research students, clinician-researchers, MRI technicians or anyone new to using of MEGA-PRESS. The guideline helps to ensure sufficient quality of acquisition and reporting is achieved. The high level of agreement between evidence and expert assessment instils confidence in the validity, longevity, and applicability of these recommendations. The full accompanying documentation is freely available online here: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BV6JN.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Funding has been received as follows: Aimie Peek Australian Postgraduate Award and Top-up Scholarship National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in recovery following road Traffic Injuries APP1079022; Trudy Rebbeck receives funding from Sydney Research Accelerator (SOAR) Fellowship and NHMRC Career Development Fellowship APP1161467; Georg Oeltzschner receives funding from National Institute of Health (NIH) National Institute on Aging R00AG062230.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2023.115113.

Contributor Information

A.L. Peek, Email: aimie.peek@sydney.edu.au.

T.J. Rebbeck, Email: trudy.rebbeck@sydney.edu.au.

A.M. Leaver, Email: andrew.leaver@sydney.edu.au.

S.L. Foster, Email: sheryl.foster@sydney.edu.au.

K.M. Refshauge, Email: kathryn.refshauge@sydney.edu.au.

N.A. Puts, Email: nicolaas.puts@kcl.ac.uk.

G. Oeltzschner, Email: goeltzs1@jhmi.edu.

MRS Expert Panel:

Ovidiu C. Andronesi, Peter B. Barker, Wolfgang Bogner, Kim M. Cecil, In-Young Choi, Dinesh K. Deelchand, Robin A. de Graaf, Ulrike Dydak, Richard AE. Edden, Uzay E. Emir, Ashley D. Harris, Alexander P. Lin, David J. Lythgoe, Mark Mikkelsen, Paul G. Mullins, Jamie Near, Gülin Öz, Caroline D. Rae, Melissa Terpstra, Stephen R. Williams, and Martin Wilson

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

Multimedia component 5.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Wood E.T., Cummings K.K., Jung J., et al. Sensory over-responsivity is related to GABAergic inhibition in thalamocortical circuits. Transl. Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):39. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01154-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puts N.A.J., Wodka E.L., Harris A.D., et al. Reduced GABA and altered somatosensory function in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2017;10(4):608–619. doi: 10.1002/aur.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolasinski J., Hinson E.L., Divanbeighi Zand A.P., Rizov A., Emir U.E., Stagg C.J. The dynamics of cortical GABA in human motor learning. J. Physiol. 2019;597(1):271–282. doi: 10.1113/JP276626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zacharopoulos G., Sella F., Cohen Kadosh K., Hartwright C., Emir U., Cohen Kadosh R. Predicting learning and achievement using GABA and glutamate concentrations in human development. PLoS Biol. 2021;19(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasbarri A., Pompili A. In: Meneses A., editor. vol. 210. Elsevier; San Diego: 2014. 3 – the role of GABA in memory processes; pp. 47–62. (Identification of Neural Markers Accompanying Memory). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peek A.L., Rebbeck T., Puts N.A., Watson J., Aguila M.E., Leaver A.M. Brain GABA and glutamate levels across pain conditions: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 1H-MRS studies using the MRS-Q quality assessment tool. Neuroimage. 2020;210 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godfrey K.E., Gardner A.C., Kwon S., Chea W., Muthukumaraswamy S.D. Differences in excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter levels between depressed patients and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018;105:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schür R.R., Draisma L.W., Wijnen J.P., et al. Brain GABA levels across psychiatric disorders: a systematic literature review and meta‐analysis of 1H‐MRS studies. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016;37(9):3337–3352. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vengeliene V., Bilbao A., Molander A., Spanagel R. Neuropharmacology of alcohol addiction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;154(2):299–315. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marotta R., Risoleo M.C., Messina G., et al. The neurochemistry of autism. Brain Sci. 2020;10(3):163. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun W., Zhou Q., Ba X., et al. Oxytocin relieves neuropathic pain through GABA release and presynaptic TRPV1 inhibition in spinal cord. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;11:248. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enna S., McCarson K.E. The role of GABA in the mediation and perception of pain. Adv. Pharmacol. 2006;54:1–27. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(06)54001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baulac S., Huberfeld G., Gourfinkel-An I., et al. First genetic evidence of GABA A receptor dysfunction in epilepsy: a mutation in the γ2-subunit gene. Nat. Genet. 2001;28(1):46–48. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coghlan S., Horder J., Inkster B., Mendez M.A., Murphy D.G., Nutt D.J. GABA system dysfunction in autism and related disorders: from synapse to symptoms. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012;36(9):2044–2055. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]