Abstract

Introduction

Pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an important HIV prevention option. Two randomized trials have provided efficacy evidence for long‐acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB‐LA) as PrEP. In considering CAB‐LA as an additional PrEP modality for people at substantial risk of HIV, it is important to understand community response to injectable PrEP. We conducted a systematic review of values, preferences and perceptions of acceptability for injectable PrEP to inform global guidance.

Methods

We searched nine databases and conference websites for peer‐reviewed and grey literature (January 2010−September 2021). There were no restrictions on location. A two‐stage review process assessed references against eligibility criteria. Data from included studies were organized by constructs from the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability.

Results

We included 62 unique references. Most studies were observational, cross‐sectional and qualitative. Over half of the studies were conducted in North America. Men who have sex with men were the most researched group. Most studies (57/62) examined injectable PrEP, including hypothetical injectables (55/57) or placebo products (2/57). Six studies examined CAB‐LA specifically. There was overall interest in and often a preference for injectable PrEP, though there was variation within and across groups and regions. Many stakeholders indicated that injectable PrEP could help address adherence challenges associated with daily or on‐demand dosing for oral PrEP and may be a better lifestyle fit for individuals seeking privacy, discretion and infrequent dosing. End‐users reported concerns, including fear of needles, injection site pain and body location, logistical challenges and waning or incomplete protection.

Discussion

Despite an overall preference for injectable PrEP, heterogeneity across groups and regions highlights the importance of enabling end‐users to choose a PrEP modality that supports effective use. Like other products, preference for injectable PrEP may change over time and end‐users may switch between prevention options. There will be a greater understanding of enacted preference as more end‐users are offered anti‐retroviral (ARV)‐containing injectables. Future research should focus on equitable implementation, including real‐time decision‐making and how trained healthcare providers can support choice.

Conclusions

Given overall acceptability, injectable PrEP should be included as part of a menu of prevention options, allowing end‐users to select the modality that suits their preferences, needs and lifestyle.

Keywords: acceptability, injectable PrEP, long‐acting injectable cabotegravir, pre‐exposure prophylaxis, PrEP, values and preferences

PROSPERO number: CRD42021285299

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite the availability of HIV prevention tools, HIV remains a significant public health issue, with approximately 1.5 million people acquiring HIV in 2021 [1]. Pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the use of antiretroviral drugs to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition among those not infected [2]. In 2021, an estimated 1.6 million people worldwide were using oral PrEP, which was under the United Nations 2025 target of 10 million people [3]. Further complicating the uptake of oral PrEP is the challenge of persistence. To be effective, oral PrEP does not need to be taken continuously, but its impact relies on adherence during periods of risk. Clinical trials have demonstrated that effectiveness is substantially higher among more adherent participants compared to overall study populations [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. Implementation studies have also demonstrated challenges to the effective use of oral PrEP during periods of risk [11], with uptake and persistence varying across at‐risk populations [12, 13]. Daily pill‐taking can be burdensome for some, including young people [14], contributing to ineffective use.

In January 2021, the dapivirine vaginal ring (DVR) became the second PrEP product recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2]. Although women have expressed interest in the DVR, particularly in east and southern Africa, some have reported discomfort with ring insertion or difficulties with effective use [15]. Newer PrEP products, especially long‐acting modalities, could increase PrEP uptake and use. In 2021, results from two randomized trials on the use of long‐acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB‐LA) as PrEP, HPTN 083 and HPTN 084, were published [16, 17]. These trials stopped early after demonstrating CAB‐LA's statistically superior efficacy at preventing HIV acquisition compared to oral tenofovir/emtricitabine among cisgender men and women and transgender (trans) women. Although CAB‐LA and oral PrEP were effective in both trials, adherence to CAB‐LA was significantly higher than for oral PrEP. In HPTN 084, 93% of women took CAB‐LA as prescribed compared with 42% of women taking oral PrEP [18]. In December 2021, CAB‐LA as PrEP gained approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adolescents and adults at risk for sexual acquisition of HIV [19], with WHO also recommending CAB‐LA as PrEP in July 2022 [20].

Understanding acceptability, interest in and views about injectable PrEP from potential end‐users is key to informing global guidelines to facilitate uptake, thereby increasing coverage of HIV prevention among populations at substantial risk. As such, we conducted a systematic review assessing end‐user and stakeholder values, preferences and perceptions of acceptability related to injectable PrEP. We included peer‐reviewed and grey literature examining all forms of injectable PrEP, including CAB‐LA, placebo injections and hypothetical injectable PrEP use.

2. METHODS

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [21]. A protocol was reviewed by the WHO and prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021285299). Database searches and article screening were conducted concurrently with a review on safety and efficacy of CAB‐LA as PrEP (CRD42021290713) [22]. Results are reported separately.

2.1. Databases and search terms

In October 2021, we searched for peer‐reviewed and grey literature in databases that sourced clinical or social and behavioural research on the use of injectable PrEP globally. We worked with a reference librarian to construct a search strategy for the following databases: PubMed, Global Health, Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, Embase and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. Abstracts from the following conferences were searched: International AIDS Conference; International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Prevention; Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; and HIV Research for Prevention Conference.

Within each database, we searched for articles published between 1 January 2010 and 27 September 2021. Because we searched for clinical as well as social and behavioural research, we opted for an inclusive search strategy that included three main constructs: injectable modalities AND PrEP/prevention AND HIV. (Supporting Information Appendix A includes a comprehensive list of terms.)

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles needed to meet eligibility criteria (Table 1). We included articles exploring values and preferences for injectable PrEP among diverse stakeholders regardless of language or location of intervention. We excluded articles that did not include primary data, those containing duplicative data or interim results if final results were available.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for the review on values and preferences for injectable pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

| Criteria | Eligibility |

|---|---|

| Article type | a. Published in peer‐reviewed journal between 1 January 2010 and 27 September 2021; OR |

| b. Presented as abstract at a scientific conference between January 2010 and September 2021; OR | |

| c. Unpublished work containing relevant data | |

| Intervention | Studies reporting primary data on injectable PrEP, including CAB‐LA, placebo products or hypothetical injectable PrEP use |

| Study population | a. Populations at substantial risk of HIV acquisition; OR |

| b. Healthcare workers/stakeholders involved in any aspect of provision of injectable PrEP | |

| Study design | a. Qualitative studies, including in‐depth interviews or focus group discussions; OR |

| b. Experimental or non‐experimental studies quantitatively evaluating the use of injectable PrEP to prevent HIV among people at substantial risk of HIV infection | |

| Key outcomes | a. Awareness of injectable PrEP |

| b. Values and preferences related to injectable PrEP | |

| c. Feasibility a , acceptability b or satisfaction c with injectable PrEP | |

| d. Concerns regarding injectable PrEP | |

| e. Willingness to use injectable PrEP | |

| f. Barriers and facilitators of injectable PrEP use |

Feasibility is defined as “the extent to which a new treatment, or an innovation, can be successfully used or carried out within a given agency or setting” [23, 24].

Acceptability is defined as “a multi‐faceted construct that reflects the extent to which people delivering or receiving a healthcare intervention consider it to be appropriate, based on anticipated or experienced cognitive and emotional responses to the intervention” [25].

Satisfaction is “the state of being content or fulfilled with a service or intervention based on one's needs and desires or being content with the general service‐delivery experience” [26]. Abbreviations: PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis; CAB‐LA, long‐acting injectable cabotegravir.

2.3. Citation screening, data management and analysis

After conducting database searches, a de‐duplicated list of references was uploaded into Covidence, a systematic review screening and data management software. Four reviewers used a multi‐phase screening strategy to determine inclusion (stage 1: title/abstract review; stage 2: full‐text review). Disagreements were resolved by consensus through team discussions. Quantitative and qualitative data were extracted independently by two reviewers using a standardized Excel‐based form. Differences in data extraction were also resolved through consensus. We gathered the following from each included study: (1) study identification: authors, reference type and publication year; (2) description: objectives, location, population characteristics, intervention description, study design and sample size; and (3) outcomes: quantitative or qualitative measures, main findings, strengths, limitations and conclusions. We also coded references to relevant constructs from the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA; Table 2) [25].

Table 2.

Constructs of acceptability for injectable PrEP, adapted from the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability developed by Sekhon et al. [25]

| Construct | Operationalization | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Affective attitude | Overall feelings about an intervention | Satisfaction with, overall acceptability, liking or recommending injectable PrEP |

| Burden | Perceived amount of effort to participate in the intervention | Ease of use and facilitators; perceived challenges or concerns related to injectable PrEP |

| Ethicality | Extent of fit with an individual's value system | Discretion of product use; fitting with lifestyle preferences; perceived stigma |

| Intervention coherence | Extent that participant understands the intervention/how it works | Understanding how injectable PrEP prevents HIV |

| Opportunity costs | Extent that benefits, profits or values must be given up to engage in the intervention | Trade‐offs of taking injectable PrEP |

| Perceived effectiveness | Perception that intervention is likely to achieve its purpose | Degree of protection; perceived ability of injectable PrEP to prevent HIV |

| Self‐efficacy | Participant's confidence that they can perform the behaviours required to participate in the intervention | Ability to use/adhere to injectable PrEP; ability to regularly attend clinic visits to receive the injections |

Abbreviation: PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis.

Findings were summarized and reported in narrative and tabular formats. Results are organized by constructs from the TFA. Peer‐reviewed articles were also assessed for risk of bias using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools [27], a suite of checklists available by study design. After selecting the appropriate checklist based on each study's design, the research team appraised each article and summarized the results.

3. RESULTS

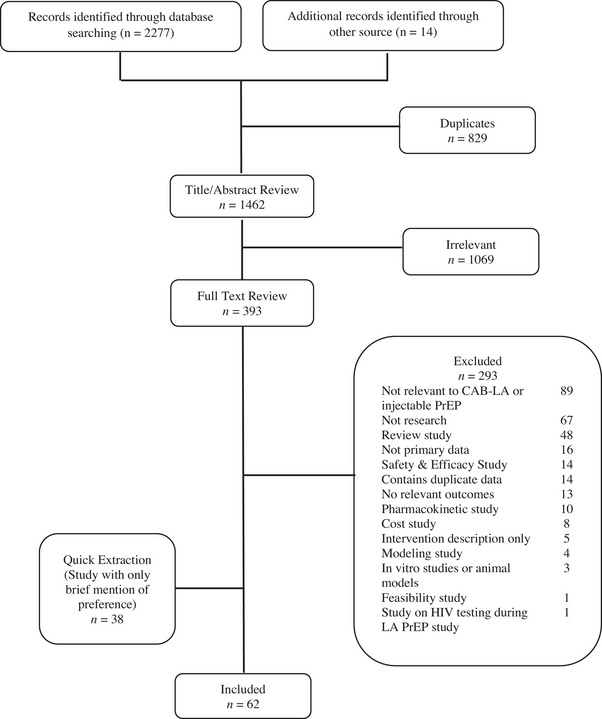

We identified 2277 records through our database search and 14 records through other sources, yielding 1462 unique records (Figure 1). Ultimately, 100 records met inclusion criteria; 62 records (53 articles and 9 abstracts) were fully extracted and organized below by acceptability constructs and groups, with findings specific to CAB‐LA also reported separately. Thirty‐eight records briefly mentioned preferences for injectable PrEP (e.g. abstracts with few details, articles including only one question mentioning injectable PrEP) and were extracted separately (Supporting Information Appendix B).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

3.1. Study characteristics

Of 62 records, most were observational, cross‐sectional and qualitative studies examining end‐user values and preferences in approximately 41 countries (one report included participants from 29 unnamed countries), with over 50% of articles from North America and one‐third from sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA; Table 3). Most examined injectable PrEP generally, including hypothetical or placebo injections. Six studies examined CAB‐LA specifically. Men who have sex with men (MSM) were the most researched group. Table 4 summarizes the results from included studies.

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies included in detailed extraction

| Characteristics | N of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Study type | |

| Peer‐reviewed | 53 (85) |

| Grey literature | 9 (15) |

| Study design | |

| Observational study | 58 (94) |

| Randomized control trial | 4 (6) |

| Location a | |

| North America | 35 (57) |

| Sub‐Saharan Africa | 19 (31) |

| East Asia and Pacific | 5 (8) |

| Europe and Central Asia | 5 (8) |

| Latin American and the Caribbean | 2 (3) |

| South Asia | 2 (3) |

| Modality | |

| Injectable (generic) | 53 (85) |

| CAB‐LA | 6 (10) |

| Injectable multipurpose prevention technology | 2 (3) |

| Rilpivirine | 1 (2) |

| Group identifier b | |

| MSM | 26 (42) |

| Women only | 11 (18) |

| Adolescents and young people | 8 (13) |

| Current PrEP users | 8 (13) |

| Trans women and men | 6 (10) |

| Care providers | 5 (8) |

| People who inject drugs | 5 (8) |

| Sex workers (male and female) | 5 (8) |

| JBI checklist c | |

| Qualitative | 27 (51) |

| Cross‐sectional | 22 (41) |

| Randomized control trial | 4 (8) |

A study could include more than one location. Geographic locations were defined according to World Bank Classifications.

A study could include more than one group identifier.

Only full‐text peer‐reviewed articles were assessed with a JBI checklist. Abbreviations: PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute.

Table 4.

Summary of studies included in detailed extraction

| Specific group | First author, et al. (year) | Region | Study design category | Sample size | Product assessed | Main findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM | Meyers, K. et al. (2014) | North America | Observational study | 197 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[28] |

| Chakrapani, V. et al. (2015) | South Asia | Observational study | 26 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[29] | |

| Meyers, K. et al. (2016) | North America | Observational study | 62 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[30] | |

| Oldenburg, C. E. et al. (2016) | East Asia and Pacific | Observational study | 548 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[31] | |

| Parsons, J. T. et al. (2016) | North America | Observational study | 948 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[32] | |

| Greene, G. J. et al. (2017) | North America | Observational study | 512 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[33] | |

| Ngongo, P. B. et al. (2017) | Africa | Observational study | 165 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[34] | |

| Beymer, M. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 761 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[35] | |

| Biello, K. B. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 36 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[36] | |

| Calder, B. J. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 21 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[37] | |

| Dubov, A. et al. (2018) | Europe and Central Asia | Observational study | 1184 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[38] | |

| John, S. A. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 104 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[39] | |

| Kerrigan, D. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 26 |

CAB‐LA (enacted preference) |

|

[40] | |

|

Meyers, K. et al. (2018) |

North America | Observational study | 28 | CAB‐LA (enacted preference) |

|

[41] | |

| Meyers, K. et al. (2018) | East Asia and Pacific | Observational study | 200 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[42] | |

| Murray, M. I. et al. (2018) | North America | Randomized control trial | 115 | CAB‐LA (enacted preference) |

|

[43] | |

| Patel, R. R. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 26 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[44] | |

| Dubov, A et al. (2019) | Europe and Central Asia | Observational study | 554 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[45] | |

| Ellison, J. et al. (2019) | North America | Observational study | 108 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[46] | |

| Peng, L. et al. (2019) | East Asia and Pacific | Observational study | 524 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[47] | |

| Minnis, A. M. et al. (2020) | Africa | Observational study | 807 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[48] | |

| Torres, T. et al. (2020) | Latin American and the Caribbean | Observational study | 19,457 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[49] | |

| Gutierrez, J. I. et al. (2021) | North America | Observational study | 429 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[50] | |

| Macapagal, K. et al. (2021) | North America | Observational study | 59 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[51] | |

| Mansergh, G. et al. (2021) | North America | Observational study | 782 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[52] | |

| Nguyen, L. H. et al. (2021) | East Asia and Pacific | Observational study | 30 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[53] | |

| Women | |||||||

| Luecke, E. H. et al. (2016) | Africa | Observational study | 68 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[54] | |

| van der Straten, A. et al. (2017) | Africa | Observational study | 71 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) | This study was conducted within ASPIRE, a phase III randomized controlled trial of a vaginal ring, with all women being ring experienced.

|

[55] | |

| Minnis, A. M. et al. (2018) | Africa | Randomized control trial | 258 | MPT injections (placebo products) |

|

[56] | |

| Quaife, M. et al. (2018) | Africa | Observational study | 609 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[57] | |

| Minnis, A. M. et al. (2019) | Africa | Randomized control trial | 523 | MPT injections (placebo products) |

|

[58] | |

| Tolley, E. E. et al. (2019) | North American, Africa | Observational study | 136 | Rilpivirine (enacted preference) |

|

[59] | |

| Calabrese, S. K. et al. (2020) | North America | Observational study | 563 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[13] | |

| Dauria, E. F. et al. (2021) | North America | Observational study | 27 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[60] | |

| Philbin, M. M. et al. (2021) | North America | Observational study | 59 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[61] | |

| Philbin, M. M. et al. (2021) | North America | Observational study | 30 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[62] | |

| Tolley, E. et al. (2022) | Africa | Observational study | 68 | CAB‐LA (enacted preference) |

|

[63] | |

| Adolescents and young people | |||||||

| Mack, N. et al. (2014) | Africa | Observational study | 133 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[64] | |

| Ngongo, P. B. et al. (2017) | Africa | Observational study | 165 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) | There was a difference of opinion on mode of administration, with healthcare providers and MSM preferring oral PrEP and other groups (FSW, youth) opting for injectable PrEP. | [34] | |

| Quaife, M. et al. (2018) | Africa | Observational study | 609 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) | Adult women and FSWs significantly disliked oral PrEP and favoured injectable products. Neither adult women nor adolescent girls found the vaginal ring appealing but an injectable product was favoured by all groups. | [57] | |

| Montgomery, E. T. et al. (2019) | Africa | Observational study | 95 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[65] | |

| Taggart, T. et al. (2019) | North America | Observational study | 200 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[66] | |

| Golub, S. A. et al. (2020) | North America | Observational study | 93 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[67] | |

| Kidman, R. et al. (2020) | Africa | Observational study | 2085 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[68] | |

| Minnis, A. M. et al. (2020) | Africa | Observational study | 807 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[48] | |

| PrEP users | |||||||

| Meyers, K. et al. (2016) | North America | Observational study | 62 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[30] | |

| John, S. A. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 104 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[39] | |

|

|||||||

| Meyers, K. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 28 | CAB‐LA (enacted preference) |

|

[41] | |

| Meyers, K. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 105 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[69] | |

| Ellison, J. et al. (2019) | North America | Observational study | 108 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[46] | |

| Montgomery, E. T. et al. (2019) | Africa | Observational study | 95 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[65] | |

| Slama, L. et al. (2019) | Europe and Central Asia | Observational study | 200 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[70] | |

| Carillon, S. et al. (2020) | Europe and Central Asia | Observational study | 28 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[71] | |

| Transgender men and women | |||||||

|

Meyers, K. et al. (2018) |

North America | Observational study | 28 | CAB‐LA (enacted preference) |

|

[41] | |

| Rael, C. T. et al. (2020) | North America | Observational study | 19 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[72] | |

| Appenroth, M. et al. (2021) | North America, Africa, East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin American | Observational study | 50 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[73] | |

| Ashodaya Samithi (2021) | South Asia | Observational study | 165 | CAB‐LA (hypothetical products) |

|

[74] | |

| Poteat, T. et al. (2021) | Africa | Observational study | 36 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[75] | |

| Tagliaferri Rael, C. et al. (2021) | North America | Observational study | 15 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[76] | |

| Care providers | |||||||

| Ngongo, P. B. et al. (2017) | Africa | Observational study | 165 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) | There was a difference of opinion on mode of administration, with healthcare providers and MSM preferring oral PrEP and other groups (FSW, youth) opting for injectable PrEP. | [34] | |

|

Calder, B. J. et al. (2018) |

North America | Observational study | 21 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) | Medical practitioners recognized that injections and implants could ensure better adherence but were sceptical that achieving better adherence would motivate MSM to choose them over daily oral PrEP. | [37] | |

| Kerrigan, D. et al. (2018) | North America | Observational study | 26 |

CAB‐LA (enacted preference) |

Some providers may be more cautious in prescribing injectable versus oral PrEP as it is harder to clinically manage and more difficult to discontinue quickly. | [40] | |

| Hershow, R. B. et al. (2019) | North America | Observational study | 20 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[77] | |

| Xavier Hall, C. D. et al. (2021) | North America | Observational study | 11 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[78] | |

| PWID | |||||||

| Biello, K. B et al. (2019) | North America | Observational study | 33 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[79] | |

| Footer, K. H. A. et al. (2019) | North America | Observational study | 31 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[80] |

|

| Allen, S. et al. (2020) | North America | Observational study | 48 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[81] |

|

| Shrestha, R. et al. (2020) | North America | Observational study | 234 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[82] | |

| International Network of People Who Inject Drug (2022) | Not available | Observational study | Not available | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[83] | |

| Sex workers | |||||||

| Mack, N. et al. (2014) | Africa | Observational study | 133 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) | In Kenya, the majority of FSW preferred an injectable over other formulations because one dose would last for a prolonged period and require little user intervention. Injections were perceived as relatively private. A few women described alcohol use as potentially interfering with their ability to take daily pill but not posing a problem with injections. | [64] | |

| Quaife, M. et al. (2018) | Africa | Observational study | 609 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[57] | |

|

Minnis, A. M. et al. (2020) |

Africa | Observational study | 807 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[48] | |

| Ashodaya Samithi (2021) | South Asia | Observational study | 165 | CAB‐LA (hypothetical products) |

|

[74] | |

| Footer, K. H. A. et al. (2019) | North America | Observational study | 31 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[80] | |

| Other populations | |||||||

| Adults reside in high‐burden districts | Govender, E. et al. (2018) | Africa | Observational study | 112 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[84] |

| Heterosexual men | Cheng, ChihYuan et al. (2019) | Africa | Observational study | 202 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[85] |

| Adults reside in fishing communities | Kuteesa, M. O. et al. (2019) | Africa | Observational study | 805 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[86] |

| HIV‐uninfected healthy at‐risk adults | Laher, F. et al. (2020) | Africa | Observational study | 38 | Injectable PrEP (hypothetical products) |

|

[87] |

|

|||||||

| Healthy adults at low HIV risk | Tolley, E. E. et al. (2020) | North America, Africa, Latin American and Caribbean | Randomized control trial | 199 | CAB‐LA (enacted preference) |

|

[88] |

|

|||||||

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odd ratios; CAB‐LA, long‐acting injectable cabotegravir; CI, confidence interval; DCE, discrete choice experiment; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FIIP, future interests in injectable PrEP; FSW, female sex worker; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MPTs, multipurpose prevention technologies; MSM, men who have sex with men; MSW, male sex worker; PrEP, pre‐exposure prophylaxis; PWID, persons who inject drugs; WWID, women who inject drugs.

3.2. Quality assessment

We assessed 53 full‐text articles for risk of bias using JBI criteria. Overall, included studies met most checklist criteria, indicating a low‐to‐medium risk of bias for individual studies. There were specific limitations by the study design/checklist. For example, across 27 qualitative studies, all lacked a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically. Only one mentioned the influence of the researcher on the research and vice versa. We applied the JBI checklist for cross‐sectional studies to 22 references with quantitative outcomes. All used appropriate statistical analysis; however, five did not identify confounding factors or state strategies to address them. Four studies were assessed with the checklist for randomized controlled trials, but none met all criteria. The main limitation was a lack of clarity as to whether the outcome assessors were blinded to treatment assignments and if participants were analysed in the groups to which they were randomized.

3.3. CAB‐LA‐specific findings

Six studies examined values and preferences for CAB‐LA: three from the ECLAIR trial [40, 41, 43]; one each from HPTN 077 [88] and HPTN 084 [63]; and a qualitative study with sex workers (men, women, trans women) in India [74]. Across ECLAIR, a U.S.‐based placebo‐controlled trial among men at low risk for acquiring HIV, participants reported willingness to use or high satisfaction with CAB‐LA [40, 41, 43]. Injection pain was common [41], yet most reported satisfaction with the product despite side effects and pain/discomfort [43]. HPTN 084 participants overwhelmingly preferred CAB‐LA to daily oral PrEP [63]. Most HPTN 077 participants found the number, frequency and location of injections initially acceptable [80], though future interest in CAB‐LA was higher in non‐U.S. sites. HPTN 077 participants in the placebo arm reported higher acceptability of physical experiences [88]; however, there was no relationship between injection site pain and future interest in CAB‐LA [88]. ECLAIR participants and SSA women from HPTN 084 appreciated that CAB‐LA afforded more privacy and improved adherence over pills [16, 63]. Finally, sex workers in India were willing to use CAB‐LA, especially those with prior oral PrEP or depot‐medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) experience [74].

3.4. Affective attitude

Nearly, all studies reported on affective attitude (Table 5). Most explored stated preference (i.e. preference for hypothetical products or attributes). Less common were reports of enacted preference (i.e. experimentation with multiple modalities and subsequent choice of a preferred product) or preference based on experience with placebos or active injectables. Where possible, we provide details to clarify enacted preference or preference based on experience.

Table 5.

Overview of articles by acceptability constructs and groups

| MSM | Women | Trans men and women | Adolescents and young people | PWID | Care providers | Sex workers (male and female) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective attitude | [28, 31–45, 47–50, 52, 69, 85] | [34, 48, 55, 57–61, 63, 64, 74, 84, 86, 88] | [34, 51, 64, 66, 68] | [61, 77, 79‐83] | [34] | ||

| Burden—ease of use and facilitator | |||||||

| Ease of use and convenience | [33, 37, 46, 71] | [62, 87] | [78] | ||||

| Injections circumvent daily pill‐taking burden | [31, 53, 69] | [72, 75] | [79, 80] | ||||

| Fit with family planning | [61, 64, 74, 84] | [74] | |||||

| Frequency of injection | [32, 44] | [48] | [76] | [51] | |||

| Trained, sensitive providers | [44] | [55] | |||||

| Burden—concerns and challenges | |||||||

| Dislike/fear of needles and pain | [33, 37, 39, 41, 44, 46] | [59, 61, 63, 65] | [61, 79] | [55, 64, 74] | |||

| Side effects | [32, 33, 36, 39, 40] | [62] | [79, 80, 82] | ||||

| Invasiveness and body location of the injection | [40, 41, 48] | [55] | [48, 64] | ||||

| Logistical challenges | [36, 46, 69, 73] | [62] | [36, 46, 73] | [51] | |||

| Lack of control | [37, 69] | [55] | |||||

| Ethicality | [29, 31, 69] | [61, 62, 64, 65, 84, 86] | [72, 73, 75, 76] | [51] | [61, 79] | [64] | |

| Intervention coherence | [67] | ||||||

| Opportunity costs | [84] | [74, 82] | [79] | [74] | |||

| Perceived effectiveness | [36, 39, 40, 69] | [62] | [65] | [82] | [77] | ||

| Self‐efficacy | [68] | [79, 80] | [74] |

Abbreviations: PWID, persons who inject drugs.

3.4.1. U.S.‐based MSM

Injectable PrEP was often, though inconsistently, preferred among U.S.‐based MSM. ECLAIR participants reported higher satisfaction with CAB‐LA over oral PrEP and higher interest in future use [40, 43]. Although 25% of participants receiving CAB‐LA were dissatisfied with the pain/discomfort associated with the injection, 74% were satisfied enough to continue CAB‐LA [43]. Other studies also reported a willingness to receive injectable PrEP [28] or a preference for injectable PrEP compared to daily oral PrEP [32, 39, 44, 46], on‐demand PrEP [35, 52], penile or rectal gels or anal suppositories [44, 52]. However, two studies reported a preference for subdermal implants over injectables [33, 46]. Others reported a preference for daily oral PrEP over injectables [33], since adherence to daily oral PrEP was already high [37]. Overall, there were conflicting reports about how oral PrEP experience influenced preferences. Two studies reported greater interest in potentially using injectable PrEP among oral PrEP‐naïve versus oral PrEP‐experienced participants [36, 50], but a third study reported daily PrEP users as more likely to endorse future injectable PrEP use [52]. Some MSM noted the value of long‐acting PrEP could increase if proven more effective or lower cost than oral PrEP [37]. Three studies noted a preference for the most effective method [32, 33, 36].

U.S.‐based adolescents assigned male at birth more often preferred condoms or yearly implants compared with injectables or quarterly implants [51]. More Black and Latino MSM youth preferred daily oral PrEP, followed by PrEP implants, then injectables [66].

3.4.2. MSM in other regions

Globally, preferences for injectable PrEP among MSM varied. MSM in India preferred injectables administered monthly or every 2 months over daily oral PrEP [29]. In China, most were willing to use injectable PrEP over pills [42] or willing to use on‐demand PrEP, followed by injectable PrEP, then daily oral pills [47]. Meanwhile, MSM reported a preference for rectal microbicide gels over injectables in Vietnam [31], oral PrEP over injectables in Kenya [34], injectables over implants in South Africa [48] and injectables followed by daily PrEP, then on‐demand PrEP in Latin America [49]. Ukrainian choice‐based analyses reported a stated preference for injectable PrEP for younger [45], well‐educated MSM [38, 45] and those living off a lower income [38], with cost an important consideration.

3.4.3. Trans men and women

Values and preferences research among trans men and women was typically grouped with MSM, making it challenging to disentangle findings for the trans community. Of the disaggregated research on affective attitudes, trans women in SSA reported preferring injectables to oral or topical formulations [75], trans women sex workers in India reported excitement for CAB‐LA [74], and trans men and women from various geographies in a multi‐country report often referred to injectables as the preferred PrEP modality [73].

3.4.4. Cisgender adult women and adolescent girls

Feelings towards injectable PrEP also varied among heterosexual, cisgender women. In the U.S., there was a slight preference for pills over injections in a study presenting different PrEP modalities [13] but a preference for injectable PrEP over daily pills in others [60, 61]. Some preferred injectables given familiarity with injections for other medications/drugs [60].

Interest in injectable PrEP also varied in SSA, though several studies highlighted a strong preference for injectables. In a qualitative sub‐study assessing preferences for HIV prevention formulations among participants in a phase III trial of DVR, the ring was most preferred, followed by implants, injectables, male condoms, then oral pills [55]. In a discrete choice experiment, Ugandan women reported comparable levels of demand for oral PrEP, injectables and implants [86]. However, in several SSA studies, women reported preferences for injectable or implantable formulations over daily oral PrEP [34, 48, 54, 57, 64, 84]. Women in HPTN 084 reported an overwhelming preference for CAB‐LA compared to daily oral PrEP [63]. African women in HPTN 076 (assessing rilpivirine injections) more strongly endorsed injectable PrEP than U.S.‐based participants, and even more so if the injectable offered HIV and pregnancy prevention together [59].

In the TRIO study, which compared women's modality preferences for placebo multi‐purpose prevention technologies (MPTs) in South Africa and Kenya, injections were the most popular modality (over oral pills or vaginal rings) and achieved the highest adherence [58]. However, more participants stated they would choose an MPT ring or pill over an injection that solely prevented HIV [58]. Sex workers in India had a higher willingness to use CAB‐LA if they had previous exposure to oral PrEP or DMPA [74]. Finally, adolescent girls and young women in SSA [34, 64, 68] reported a preference for injections over daily pills. In a study of MPTs in SSA, participants rated the acceptability of injectables significantly higher than for rings or pills [89]. Malawian adolescents were particularly interested in facility‐based injections [68].

3.4.5. PWID

Compared to some groups, values and preferences research is lacking for persons who inject drugs (PWID). Among studies examining U.S.‐based PWID, there was greater interest in injectables [79, 82] or implants [80] compared with daily oral PrEP, given irregular visits to primary health centres. PWID [81] and providers [77] reported that the availability of injectable PrEP could alleviate barriers to PrEP adherence for PWID. Some indicated that other PWID would be willing to try injectable PrEP given familiarity with needles [61, 79]. Despite low awareness of injectable PrEP, PWID from a multi‐regional assessment reported a preference for injectable PrEP over daily oral PrEP due to greater perceived efficacy, tolerability and convenience [83].

3.5. Burden—ease of use and facilitators

Following affective attitude, burden was the most commonly reported TFA construct (reported in 34 references), including ease of use, facilitators or challenges.

3.5.1. Ease of use and convenience

ECLAIR participants reported relative ease of use of injectables compared to oral PrEP, which reduced long‐term adherence concerns [40]. Among MSM, injectable PrEP was considered an easy‐to‐use, convenient option compared to daily pills [33, 46] that provided privacy and adequate duration of protection [33]. Some MSM noted that injectables presented a therapeutic simplification over oral PrEP that suited busy lifestyles [37, 71]. U.S.‐based women also reported injectable PrEP as convenient [62]. South African women in a vaccine efficacy trial reported that injectable PrEP fulfilled the need for an effective, discreet method requiring infrequent administration [87].

3.5.2. Injections circumvent daily pill‐taking burden

A major benefit of injectables was the reduced burden of daily pill‐taking. Current PrEP users were more likely to see not forgetting doses as an advantage of injectables compared to people living with HIV (PLWH) [70]. ECLAIR participants and women in MTN‐003D (assessed preferences for oral PrEP, gel and other formulations [54]) reported the relative ease‐of‐use of injectables and implantables reduced end‐users’ fears about maintaining long‐term adherence. Women in HPTN 084 said injections circumvented fears of forgetting to take pills, which could happen due to lifestyle considerations, such as late‐night work, travel or drinking alcohol [63]. Similarly, PWID reported that injectable PrEP reduced concerns about daily dosing [80] and more easily fit into clinical care schedules [79].

MSM in Vietnam [31, 53] and U.S.‐based Black and Latino youth [66] and MSM [69] reported injectable PrEP as beneficial to reducing the anxiety of remembering to take a daily pill. Trans women in South Africa specifically noted that dislike of daily dosing was a common reason for preferring injectable formulations [75], while U.S.‐based trans women appreciated not having to adhere to a daily product to have reliable protection [72]. Some U.S.‐based providers said injections could reduce the burden of remembering to take daily pills for users, yet dosing schedules and frequency of visits were cautioned as adherence barriers [78].

3.5.3. Fit with family planning

In the U.S. and South Africa, adult [13, 61, 84] and young women [64] reported that injectables fit into existing family planning routines and modalities for some (e.g. receiving contraceptive injectables in the buttocks), which was an important facilitator of injectable PrEP use. Some female sex workers (FSWs) in India compared CAB‐LA with taking DMPA [74].

3.5.4. Frequency of injection

Frequency of injection was an important attribute, including among U.S.‐based MSM who found a 3‐month (or longer) injectable preferable to shorter durations [32, 44]. Some South African women preferred receiving bimonthly injectable PrEP at a health facility but would consider a pharmacy if dosed less frequently [48]. For U.S.‐based sexual and gender minority adolescents, ease of use would be supported by administration in the arm, reducing the number of annual injections, and—though not yet recommended—self‐administration similar to gender‐affirming hormones [51]. Many U.S.‐based trans women also favoured self‐injection, though acknowledged this could yield errors [76].

3.5.5. Trained, sensitive providers

Some ECLAIR participants felt that friendly nurses trained to give intramuscular injections would improve injectable PrEP use [41]. Per U.S.‐based MSM, attitudes or behaviours of personnel administering the injection could affect preferences for this modality [44]. Some women in SSA expressed concerns about the qualifications of clinical staff to perform “invasive procedures” like injections [55].

3.6. Burden—concerns and challenges

3.6.1. Dislike/fear of needles and pain

Dislike or fear of needles was mentioned by FSWs and other women in SSA and India [55, 64, 74], adolescents in Malawi [68] and South Africa [64], U.S.‐based MSM [33, 41, 44, 46], and former injection drug users and other women in the U.S. [61, 63, 79]. Some former PWID found the use of needles “triggering,” as they were reminders of their history of drug use. However, dislike/fear of needles was somewhat countered by the high level of protection provided by injectable PrEP [44]. Some experienced PrEP users also reported fear of poorly administered injections [71]. Several young women in an MPT trial in South Africa [89] and many women in the rilpivirine trial [59] noted fear of pain upon initially seeing the needle, though this typically subsided after experiencing the injection. Few rilpivirine trial participants reported pain as unacceptable [59]. South African women also acknowledged that pain is temporary following injection, and soreness subsides [65].

3.6.2. Side effects

Concerns over side effects, including not having control over side effects, were mentioned by PWID [79, 80], adolescents [51] and MSM [32, 36, 39]. Some U.S.‐based women reported that side effects, including potential interference with pregnancy, were barriers to uptake [62]. Despite concerns over side effects, ECLAIR participants noted a willingness to deal with CAB‐LA side effects if found to be effective [40]. Beyond side effects, MSM [32, 39] and PWID [82] in the U.S. expressed concerns over the long‐term effects of injectable PrEP.

3.6.3. Invasiveness and body location of the injection

Invasiveness of injection location (i.e. buttocks) was a barrier for women shown hypothetical prevention modalities at the end of a DVR trial in SSA [55]. Adolescent girls in South Africa were uncomfortable with having to remove their skirts for the injection, instead preferring an injection in the arm [48, 64]. Several ECLAIR participants also noted embarrassment from needing to expose one's buttocks [40, 41], and some MSM and heterosexual men in South Africa had concerns about the buttocks as an injection site [48].

3.6.4. Logistical challenges

MSM and trans people expressed logistical concerns, including needing to regularly return for appointments [36, 46, 73]. By contrast, regular visits were not considered a barrier by some U.S.‐based MSM currently using oral PrEP since it also required regular clinical visits [69]. Logistics were a concern for men in a PrEP demonstration project inconvenienced by scheduling follow‐up appointments [69]. U.S.‐based women were concerned with appointment frequency [62], and adolescents disliked how injectable PrEP has a short duration/coverage, requiring frequent appointments [51].

3.6.5. Lack of control

MSM mentioned lack of control over their bodies and medication administration, particularly compared to pills that are fully under user control, as a disadvantage of injectables [37, 69]. Lack of control worried PrEP‐experienced users [71], who were more likely to see the loss of control or adverse effects as barriers to injectables than PLWH [70]. In a PrEP demonstration project, men liked the control of taking a daily pill over using an injectable [69]. Women in SSA expressed concern about injectable reversibility, that is the ability to remove or discontinue product use if there are concerns about safety or side effects [55].

3.7. Ethicality

Sixteen studies reported on ethicality [29, 31, 40, 51, 54, 61–65, 69, 79, 84, 86, 89, 90]. One of the most desirable aspects of injectable PrEP was its ability to be concealed. Women in the U.S. [62], FSWs in South Africa [64, 78] and young women using placebo MPTs in SSA [89] described injectables as offering discretion and confidentiality. Participants in CAB‐LA studies also noted a preference for injectables by those valuing confidentiality, as injectables afford more privacy than pills [40, 63]. SSA women reported that longer‐lasting products were more acceptable to women valuing secrecy [86], discretion and invisibility [65] as well as women needing maximum protection and minimal partner negotiation [84]. Facility‐based administration was appealing for women hiding pills at home from partners, family or children [54]. MSM in several studies also reported that injectable PrEP obviates the need to conceal PrEP at home or carry pills while travelling [29, 31, 69]. Adolescents assigned male at birth also liked that injectables could be easily concealed and included as part of routine check‐ups [51].

Injectable PrEP was typically considered a better fit for people comfortable with needles [40, 61, 79], though some studies challenged this assertion. Some PWID noted social or cognitive burdens in that some with a history of injection drug use, especially those in recovery, could be triggered by injections [61, 79]. Other PWID worried that injectable PrEP could “affect their high” [79]. Women with a history of medication‐related injections (e.g. insulin pumps, steroid injections, etc.) expressed reticence to add another injectable to their regimens [61].

Finally, injectables may be appropriate for the unhoused [36], those engaging in more frequent sex or those looking to reduce perceived stigma related to oral PrEP [71]. Some oral PrEP users reported that, because injectables offered discretion, they could reduce social stigma [71]. Additionally, some trans people felt that injectable PrEP reduced the risk of carrying drugs that might expose them as being vulnerable to HIV or being falsely assumed as HIV positive [73]. Nevertheless, stigma was also a barrier for trans women attending drop‐in hours at a health facility for injectable PrEP [76]. Trans women in South Africa said reducing the number of healthcare visits for injectables could mitigate discrimination from healthcare providers [75]. Some trans women reported feeling comfortable with the idea of self‐administering at home, much like gender‐affirming hormones [72].

3.8. Intervention coherence

One study addressed intervention coherence. U.S.‐based LGBTQ youth questioned how injectable PrEP would protect them, and in some cases, made incorrect assumptions about how biomedical prevention works [67]. Participants requested information about the rationale for the injection site and whether injectables would interfere with other recreational, over‐the‐counter or gender‐affirming drugs [67].

3.9. Opportunity costs

Six studies reported on opportunity costs [38, 45, 72, 74, 79, 84]. Trans women in the U.S. and India worried that injectables could interfere with gender‐affirming hormones [72, 74], with some feeling more research was necessary to explore these interactions [72]. U.S.‐based trans women also discussed the potential effect of injections in gluteal muscles due to silicone implants and concerns about scarring [72]. South African women reported concerns about weight gain and poor body image as a potential result of injectable PrEP [84]. U.S.‐based PWID raised concerns over the monetary costs of injectables relative to oral PrEP [79], and European MSM [38, 45] noted cost as a major influencer when considering different hypothetical products, ranking cost as more important than dosing frequency.

3.10. Perceived effectiveness

Nine studies addressed perceived effectiveness [36, 39, 40, 62, 65, 69, 71, 77, 82]. Some MSM were interested in CAB‐LA [40] or injectable PrEP more generally [36] because it was perceived as an effective modality, particularly in instances of unexpected HIV risk or condomless sex. Some U.S.‐based women perceived injections to be more effective than pills [62], and some South African youth perceived that injections provided greater protection than vaginal rings since the injection is systemic and readily absorbed [65]. However, others expressed concerns over the experimental nature of long‐acting anti‐retroviral therapy (ART) and PrEP, wanting more scientific evidence [71] or FDA approval [69] before using. MSM were concerned about diminishing, waning or incomplete protection associated with injectable PrEP [36, 39, 69]. Among men in a U.S.‐based PrEP demonstration project, the biggest barrier to switching to injectables included concerns about safety, efficacy and not trusting protection from a single shot [69]. Some providers of PWID were concerned over ARV resistance if participants did not return for follow‐up appointments [77]. However, PWID were less concerned about incomplete protection than longer‐term health effects [82].

3.11. Self‐efficacy

Five studies addressed self‐efficacy [68, 74, 77, 79, 80], which mapped to some logistical concerns noted under Burden given the focus on participant's assessment of their ability to adhere to injectable PrEP. There was concern among PWID [79, 80] and their providers [77] over PWID's ability to consistently attend appointments. Participants countered concerns by discussing adherence strategies [76, 79]. Worry over forgetting appointments was also reported by some Malawian adolescents [68] and sex workers in India, who were challenged by long wait times at government hospitals and not remembering appointment dates [74].

4. DISCUSSION

Since 2010, a wealth of literature has explored values, preferences and acceptability related to injectable PrEP. This review found an overall preference for and much interest in injectable PrEP, including CAB‐LA. However, there was variation in preferences within and across groups and geographies. This is consistent with evidence that preference for injectable contraceptives also varies by location, with women in low‐income countries more likely to prefer an injectable than women in high‐income countries [91]. The variation also highlights the importance of including injectable PrEP in a menu of prevention options, allowing end‐users to interface with providers to choose a PrEP modality that suits their lifestyle and supports effective use. Moreover, as this review included a variety of groups and regions, it is important to consider how individual risk perceptions are associated with interest in product use [92, 93] and acceptance [94], as has been demonstrated for oral PrEP use.

Most studies were conducted before CAB‐LA efficacy data were published and CAB‐LA had received regulatory approval, therefore, among participants who had not used CAB‐LA. Participants were typically asked about preferences for hypothetical injectables compared with other PrEP products. More recent efficacy trials have tested placebo and active injectables, including CAB‐LA, rilpivirine and lenacapavir (as a semi‐annual subcutaneous injectable [95]). Evidence now suggests that CAB‐LA is efficacious and safe for sexual exposure [96], thus receiving regulatory approval in the United States, Australia, Zimbabwe, South Africa and Malawi, which may overcome some concerns expressed within included studies. There is also increasing information on issues such as safety during pregnancy, although data remain limited.

When considering the rollout and scale‐up of injectable PrEP, policy makers and healthcare providers should consider lessons learned from the slow and inequitable uptake of oral PrEP [1]. Assessing differentiated service delivery models, addressing provider bias and creating patient‐centred decision tools may enable more equitable implementation of injectable PrEP [97], in addition to conducting research on how end‐users make real‐time decisions. Implementation plans are underway to offer CAB‐LA alongside other PrEP options [98], providing opportunities to assess how people choose, continue and switch between products. It is important to offer a choice of products to potential end‐users and that healthcare providers understand and respond to end‐users’ concerns, as identified here, to help make informed choices. As CAB‐LA becomes available, future research might also explore end‐user costs in accessing regular injections, including transportation fees to appointments, as cost was identified as a potential barrier to oral PrEP use [99].

Preferences for different modalities is driven, in part, by acceptability constructs. This is consistent with research indicating that preferences for prevention modalities depends on individual characteristics and may change over time [100]. Beyond affective attitude, for which there was no consistent pattern across groups and geographies, burden was most commonly described. Several concerns were raised, including fear of needles and/or injection site pain, side effects, invasiveness of injection location, logistical challenges and lack of control or reversibility. Nevertheless, facilitators of injectable PrEP included longer‐lasting coverage and peace of mind. Preference for injectable PrEP may also be driven by age or ethicality, with different issues influencing acceptability across groups. Injectable PrEP may be beneficial for those seeking discretion or having challenges negotiating product use with sexual partners. It may fit within the lifestyles of those experienced with taking other medicine by injection (e.g. contraceptives or gender‐affirming hormones), though unhappy associations with needle use may be concerning for PWID in recovery. Importantly, injectable PrEP presents a strong option for those having difficulty taking or unable to take daily or event‐driven PrEP, including adolescents.

4.1. Limitations

Strengths of this review include being the first to comprehensively assess acceptability for injectable PrEP. We included high‐quality literature, as indicated by a low overall risk of bias, with findings organized by a theoretical framework identifying the most salient constructs related to acceptability. This review also presents insights for various geographies and groups, including under‐researched groups like trans men and women. Although we used a systematic approach that reduced different sources of biases, some may still be present (e.g. publication bias). A key limitation is that most studies reported a preference for hypothetical products rather than enacted preference. The research was conducted prior to FDA approvals and the WHO recommendation, which affected end‐user perceptions. Values and preferences may shift as end‐users can use and choose between approved products.

Currently, CAB‐LA is recommended to prevent HIV via sexual exposure. Animal models suggest efficacy to prevent parenteral exposure [101], but research is limited, and CAB‐LA has not been specifically studied in PWID. Although PWID often have overlapping risk, this may influence their preferences. Another limitation is that certain groups or geographies are over‐represented, while others are under‐represented. We attempted to address this by stating the group/region reporting a preference, though findings suggest limited generalizability for certain groups. A limitation of CAB‐LA studies was that none presented information on injection site discreetness or lack thereof (e.g. if the injection left a visible lump or scar). Lastly, this review contained studies with different sampling methods. The quality assessments noted limitations of varying approaches, though selection bias inherent in certain designs may have captured more favourable opinions of injectables. Yet, we feel this presents a low risk to the review's interpretations given the variation in preferences reported across populations and geographies.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This review found an overall preference for and interest in injectable PrEP, including CAB‐LA, across groups and regions. Variation reinforces the inclusion of injectable PrEP as one of many prevention options offered to end‐users, whose preferences and needs may shift over time. Injectable PrEP presents an opportunity to address adherence‐related challenges associated with oral PrEP and may be a better lifestyle fit for individuals seeking discretion or are familiar with needles. However, end‐users reported concerns related to fear/pain, logistical challenges and waning levels of protection. More research is necessary to explore enacted preference for end‐users exposed to ARV‐containing injectables.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The study was conceptualized by RB, MR and RS. LL and ND drafted the study protocol with input from AVDS, VF and KR. LL, ND, VF and KR conducted the screening of citations, with AVDS helping to resolve differences in eligibility determination. LL and ND abstracted and analysed data. All co‐authors contributed to data interpretation. LL drafted the initial manuscript, with all co‐authors contributing to subsequent iterations. All co‐authors have reviewed and approved the final version.

FUNDING

This work was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) cooperative agreements 7200AA19CA00002 and 7200AA21CA00011.

DISCLAIMER

The contents are the responsibility of the EpiC and MOSAIC projects and do not necessarily reflect the views of PEPFAR, USAID or the U.S. Government. WHO staff time was supported by grants from Unitaid and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which were awarded to the World Health Organization to enable this study. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Supporting information

Supporting Information Appendix A: Full search terms for included databases

Supporting Information Appendix B: Results from rapid extraction of 38 articles briefly mentioning preferences for injectables compared with other PrEP modalities

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Allison Burns, the reference librarian at FHI 360, for devising and conducting database and conference website searches. The authors are also appreciative of all feedback provided on drafts of this work, especially from the WHO Guideline Development Group for CAB‐LA.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . HIV data and statistics. World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. HIV/AIDS JUNPo . Danger: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. 2022.

- 4. Castel AD, Magnus M, Greenberg AE. Pre‐exposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus: the past, present, and future. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28(4):563–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Kintu A, Psaros C, et al. What's love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV‐serodiscordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(5):463–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martin S, Elliott‐DeSorbo DK, Calabrese S, Wolters PL, Roby G, Brennan T, et al. A comparison of adherence assessment methods utilized in the United States: perspectives of researchers, HIV‐infected children, and their caregivers. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23(8):593–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Muchomba FM, Gearing RE, Simoni JM, El‐Bassel N. State of the science of adherence in pre‐exposure prophylaxis and microbicide trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(4):490–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sidebottom D, Ekström AM, Strömdahl S. A systematic review of adherence to oral pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV ‐ how can we improve uptake and adherence? BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization . Guidelines: updated recommendations on HIV prevention, infant diagnosis, antiretroviral initiation and monitoring. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuehn B. PrEP disparities. JAMA. 2018;320(22):2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Calabrese SK, Galvao RW, Dovidio JF, Willie TC, Safon CB, Kaplan C, et al. Contraception as a potential gateway to pre‐exposure prophylaxis: US women's pre‐exposure prophylaxis modality preferences align with their birth control practices. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2020;34(3):132–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hodges‐Mameletzis I, Fonner VA, Dalal S, Mugo N, Msimanga‐Radebe B, Baggaley R. Pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in women: current status and future directions. Drugs. 2019;79(12):1263–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Griffin JB, Ridgeway K, Montgomery E, Torjesen K, Clark R, Peterson J, et al. Vaginal ring acceptability and related preferences among women in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0224898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Delany ‐Moretlwe S, Hughes J, Bock P, Gurrion S, Hunidzarira P, Kalonji D. Long acting injectable cabotegravir is safe and effective in preventing HIV infection in cisgender women: interim results from HPTN 084. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(Suppl 1):8. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landovitz RJ, Donnell D, Clement ME, Hanscom B, Cottle L, Coelho L, et al. Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Delany‐Moretlwe S, Hughes JP, Bock P, Ouma SG, Hunidzarira P, Kalonji D, et al. Cabotegravir for the prevention of HIV‐1 in women: results from HPTN 084, a phase 3, randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10337):1779–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. FDA approves first injectable treatment for HIV pre‐exposure prevention [press release]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20. WHO . Guidelines on long‐acting injectable cabotegravir for HIV prevention. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fonner VA, Ridgeway K, van der Straten A, Lorenzetti L, Dinh N, Rodolph M, et al. Safety and efficacy of long‐acting injectable cabotegravir as pre‐exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. AIDS. 2023;37(6):957–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karsh BT. Beyond usability: designing effective technology implementation systems to promote patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(5):388–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ortblad K, Sekhon M, Wang L, Roth S, van der Straten A,. Acceptability assessment in HIV prevention and treatment intervention and service delivery research: A systematic review and qualitative analysis. AIDS Behav. 2023;27:600–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Joanna Briggs Institute . Critical Appraisal Tools. University of Adelaide, Australia; Joanna Briggs Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meyers K, Rodriguez K, Moeller RW, Gratch I, Markowitz M, Halkitis PN. High interest in a long‐acting injectable formulation of pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV in young men who have sex with men in NYC: a P18 cohort substudy. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, Mengle S, Varghese J, Nelson R, et al. Acceptability of HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and implementation challenges among men who have sex with men in India: a qualitative investigation. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(10):569–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meyers K, Golub SA. To switch or not to switch: anticipating choices in biomedical HIV prevention. HIV Research for Prevention; October 17–21, 2016; Chicago, IL; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oldenburg CE, Le B, Huyen HT, Thien DD, Quan NH, Biello KB, et al. Antiretroviral pre‐exposure prophylaxis preferences among men who have sex with men in Vietnam: results from a nationwide cross‐sectional survey. Sex Health. 2016;13(5):465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Whitfield TH, Grov C. Familiarity with and preferences for oral and long‐acting injectable HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national sample of gay and bisexual men in the U.S. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1390–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greene GJ, Swann G, Fought AJ, Carballo‐Dieguez A, Hope TJ, Kiser PF, et al. Preferences for long‐acting pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), daily oral PrEP, or condoms for HIV prevention among U.S. men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1336–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bahati Ngongo P, Mbogua J, Ndegwa J, Githuka G, Bender B, Manguyu F. A survey of stakeholder perceptions towards pre‐exposure prophylaxes and prospective HIV microbicides and vaccines in Kenya. J AIDS Clin Res. 2017;08(03):678. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beymer MR, Gildner JL, Holloway IW, Landovitz RJ. Acceptability of injectable and on‐demand pre‐exposure prophylaxis among an online sample of young men who have sex with men in California. LGBT Health. 2018;5(6):341–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Biello KB, Hosek S, Drucker MT, Belzer M, Mimiaga MJ, Marrow E, et al. Preferences for injectable PrEP among young U.S. cisgender men and transgender women and men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(7):2101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Calder BJ, Schieffer RJ, Bryndza Tfaily E, D'Aquila R, Greene GJ, Carballo‐Dieguez A, et al. Qualitative consumer research on acceptance of long‐acting pre‐exposure prophylaxis products among men having sex with men and medical practitioners in the United States. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2018;34(10):849–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dubov A, Fraenkel L, Yorick R, Ogunbajo A, Altice FL. Strategies to implement pre‐exposure prophylaxis with men who have sex with men in Ukraine. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1100–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. John SA, Whitfield THF, Rendina HJ, Parsons JT, Grov C. Will gay and bisexual men taking oral pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) switch to long‐acting injectable PrEP should it become available? AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1184–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kerrigan D, Mantsios A, Grant R, Markowitz M, Defechereux P, La Mar M, et al. Expanding the menu of HIV prevention options: a qualitative study of experiences with long‐acting injectable cabotegravir as PrEP in the context of a phase II trial in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(11):3540–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Meyers K, Rodriguez K, Brill AL, Wu Y, La Mar M, Dunbar D, et al. Lessons for patient education around long‐acting injectable PrEP: findings from a mixed‐method study of phase II trial participants. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1209–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Meyers K, Wu Y, Qian H, Sandfort T, Huang X, Xu J, et al. Interest in long‐acting injectable PrEP in a cohort of men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1217–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murray MI, Markowitz M, Frank I, Grant RM, Mayer KH, Hudson KJ, et al. Satisfaction and acceptability of cabotegravir long‐acting injectable suspension for prevention of HIV: patient perspectives from the ECLAIR trial. HIV Clin Trials. 2018;19(4):129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Patel RR, Crane JS, Lopez J, Chan PA, Liu AY, Tooba R, et al. Pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention preferences among young adult African American men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dubov A, Ogunbajo A, Altice FL, Fraenkel L. Optimizing access to PrEP based on MSM preferences: results of a discrete choice experiment. AIDS Care. 2019;31(5):545–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ellison J, van den Berg JJ, Montgomery MC, Tao J, Pashankar R, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Next‐generation HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis preferences among men who have sex with men taking daily oral pre‐exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2019;33(11):482–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Peng L, Cao W, Gu J, Hao C, Li J, Wei D, et al. Willingness to use and adhere to HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Minnis AM, Atujuna M, Browne EN, Ndwayana S, Hartmann M, Sindelo S, et al. Preferences for long‐acting pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among South African youth: results of a discrete choice experiment. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(6):e25528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Torres TS, Konda KA, Vega‐Ramirez EH, Elorreaga OA, Diaz‐Sosa D, Hoagland B, et al. MSM at high HIV risk in Latin America prefer long‐acting PrEP. 23rd International AIDS Conference; July 6–10, 2020; Virtual 2020.

- 50. Gutierrez JI, Dubov A, Altice FL, Vlahov D. Preferences for pre‐exposure prophylaxis among U.S. military men who have sex with men: results of an adaptive choice based conjoint analysis study. Mil Med Res. 2021;8(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Macapagal K, Nery‐Hurwit M, Matson M, Crosby S, Greene GJ. Perspectives on and preferences for on‐demand and long‐acting PrEP among sexual and gender minority adolescents assigned male at birth. Sex Res Social Policy. 2021;18(1):39–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mansergh G, Kota KK, Stephenson R, Hirshfield S, Sullivan P. Preference for using a variety of future HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis products among men who have sex with men in three US cities. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(1):e25664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nguyen LH, Nguyen HLT, Tran BX, Larsson M, Rocha LEC, Thorson A, et al. A qualitative assessment in acceptability and barriers to use pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men: implications for service delivery in Vietnam. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Luecke EH, Cheng H, Woeber K, Nakyanzi T, Mudekunye‐Mahaka IC, van der Straten A, et al. Stated product formulation preferences for HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis among women in the VOICE‐D (MTN‐003D) study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van der Straten A, Shapley‐Quinn MK, Reddy K, Cheng H, Etima J, Woeber K, et al. Favoring “Peace of Mind”: a qualitative study of African women's HIV prevention product formulation preferences from the MTN‐020/ASPIRE trial. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(7):305–14. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Minnis AM, Roberts ST, Agot K, Weinrib R, Ahmed K, Manenzhe K, et al. Young women's ratings of three placebo multipurpose prevention technologies for HIV and pregnancy prevention in a randomized, cross‐over study in Kenya and South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(8):2662–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Quaife M, Eakle R, Cabrera Escobar MA, Vickerman P, Kilbourne‐Brook M, Mvundura M, et al. Divergent preferences for HIV prevention: a discrete choice experiment for multipurpose HIV prevention products in South Africa. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1):120–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Minnis AM, Montgomery ET, Napierala S, Browne EN, Van der Straten A. Insights for implementation science from 2 multiphased studies with end‐users of potential multipurpose prevention technology and HIV prevention products. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82(Supplement 3):S222–S229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tolley EE, Li S, Zangeneh SZ, Atujuna M, Musara P, Justman J, et al. Acceptability of a long‐acting injectable HIV prevention product among US and African women: findings from a phase 2 clinical trial (HPTN 076). J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(10):e25408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dauria EF, Levine A, Hill SV, Tolou‐Shams M, Christopoulos K. Multilevel factors shaping awareness of and attitudes toward pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among criminal justice‐involved women. Arch Sex Behav. 2021;50(4):1743–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Philbin MM, Parish C, Bergen S, Kerrigan D, Kinnard EN, Reed SE, et al. A qualitative exploration of women's interest in long‐acting injectable antiretroviral therapy across six cities in the women's interagency HIV study: intersections with current and past injectable medication and substance use. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2021;35(1):23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Philbin MM, Parish C, Kinnard EN, Reed SE, Kerrigan D, Alcaide ML, et al. Interest in long‐acting injectable pre‐exposure prophylaxis (LAI PrEP) among women in the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS): a qualitative study across six cities in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(3):667–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]