Abstract

Candida albicans mannoprotein (MAN) administered intravenously to mice stimulates the production of splenic CD8+ effector cells which downregulate delayed hypersensitivity (DH) in immunized mice. Cytokine involvement in the induction and/or elicitation of downregulation was studied by (i) examining murine splenocytes qualitatively for mRNA for interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-10, IL-12p40, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), (ii) quantitating splenocyte mRNA for IL-12p40 by quantitative-competitive reverse transcriptase-mediated PCR, and (iii) measuring serum levels of IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 by capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, each performed at selected intervals over 96 h after giving MAN. Further, the effect of in vivo administration of anti-IL-4 on the induction and elicitation of MAN-specific DH in MAN-treated mice was measured. Expression of IL-12p40 mRNA in the spleen was reduced to near 0 during the first 24 h but rebounded thereafter. Transcripts for IL-10 were present throughout the 96-h period, whereas those for IL-4 and IFN-γ were either weak or undetectable prior to 24 to 48 h. In vivo administration of anti-IL-4 partially abrogated the downregulatory effect of MAN only when given at the time of MAN administration. Serum levels of IL-12p40, but not IL-12p70, were increased by 24 h and maximal at 48 h. The antagonistic effect of IL-12p40 could contribute to the mechanism(s) for downregulation of DH. Moreover, IL-10, IL-4, and/or IFN-γ, interacting with MAN-activated cells in the absence of biologically active IL-12, may induce the production of CD8+ downregulatory effector cells. Partial abrogation of downregulatory activity in animals treated with anti-IL-4 at the time of induction of such activity lends support to this hypothesis.

We have been investigating Candida albicans mannoprotein (MAN)-specific immunomodulation in a murine model of candidiasis. Injection of MAN intravenously (i.v.) into naive or previously immunized mice stimulates the development of a CD8+ effector cell which downregulates MAN-specific delayed hypersensitivity (DH) (24). The CD8+ cell can be detected directly in immunized mice treated with MAN, or its presence in splenocyte suspensions can be demonstrated by transfer from MAN-treated mice into immunized mice just prior to footpad testing for DH (18, 24). Cells transferred 2 to 4 days following treatment of donor mice with MAN effectively downregulate DH in immunized recipients, whereas cells transferred prior to 48 h do not. Aside from knowing that CD4+ and I-A+ cells are required for the production of CD8+ effector cells during the first 30 h following the injection of MAN (39), little is known of the process by which the CD8+ cells are induced. It is assumed, however, that cytokines play a role.

The specific cytokines, and in what sequence they might function, in the induction of downregulatory effector cells has not been well defined. However, about 10 years ago, Mosmann et al. (47, 48) described the existence of two subtypes of murine CD4+ cells, Th1 and Th2, which could be distinguished by the profile of cytokines that they secreted when activated. Numerous investigators have been analyzing the potential roles of Th1 or Th2 cytokines in various immunologic phenomena since that time. Th1 cytokines, interleukin-2 (IL-2) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), for example, appear to have prominent roles in cellular immunity, whereas the Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 drive antibody production. Another cytokine, produced predominantly by antigen-presenting cells, IL-12, is believed to be the initiator of cellular immunity (62) and a key modulator of the immune system in general (65, 70). It has been suggested that IL-12 stimulates Th1 cells (62) and simultaneously blocks the differentiation of Th2 cells (45).

Only a few investigators have examined the role of cytokines with respect to downregulation. Notably, Schmitt et al. (61), Ullrich (67), and Rivas and Ullrich (52, 53), working with a model involving the induction of suppression by UV radiation, have determined that UV-induced immune suppression resulted from the secretion of keratinocyte-derived IL-10. IL-4 may also be involved in the immune suppression, as the administration of anti-IL-4 or anti-IL-10 resulted in the abrogation of suppression (53). The administration of exogenous IL-12 prevented the induction of immune suppression by UV and also prevented the activity of preformed suppressor cells (61). In one of the few fungal models in which cytokine involvement in downregulation has been studied, increased secretion of IL-5 and decreased secretion of IFN-γ and IL-2 were detected (7).

In this study, we analyzed the pattern and kinetics of cytokine mRNA expression in unfractionated spleen cells taken from control and MAN-treated mice. Emphasis was placed on selected cytokines produced by Th1 and Th2 cells, IL-2/IFN-γ and IL-4/IL-10, respectively, as well as on IL-12. In addition, we measured IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 production by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Further, the effect of anti-IL-4 administered to immunized and/or downregulated mice was determined. It was clear that IL-4 participated in the induction of downregulation, but there appeared to be other factors involved as well, as only partial abrogation of downregulatory activity was observed. Moreover, increased serum levels of IL-12p40, a potential antagonist of IL-12p70 (29, 33, 44), may well have permitted the establishment of the CD8+ effector cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

Male CBA/J mice, 6 to 8 weeks of age, were obtained from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine. All mice were housed in bioclean hoods and fed mouse chow and water ad libitum.

Preparation and administration of MAN.

MAN was prepared as previously described (18) from C. albicans 20A, a serotype A isolate originally obtained from Errol Reiss, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga., using the method of Peat et al. (51) as modified by Kocourek and Ballou (37). Briefly, the procedure involves autoclaving C. albicans cells in a citrate buffer to solubilize the mannoprotein, precipitation of the polysaccharide with Fehling’s solution, dissolution of the polysaccharide-copper complexes in HCl to remove the copper, and then dialyzing the preparation against distilled water to remove any low-molecular-weight components. MAN extracted in this manner contains approximately 5% protein, and mannose is the only sugar detectable (18, 51). The extract was lyophilized and stored in a desiccator prior to use.

Mice were injected i.v. with 500 μg of MAN dissolved in 200 μl of sterile nonpyrogenic saline (NPS), the most appropriate dose as determined in previous studies (18). Animals were sacrificed, and splenocyte populations were prepared at 2, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h for isolation of RNA. Data were collected from five separate experiments. Six-hour observations were made in only one experiment, however.

Preparation of splenic homogenates and isolation of poly(A)+ RNA.

Total RNA was first isolated by homogenizing spleens in 2 ml of guanidinium buffer (4 M guanidinium isothiocyanate, 0.5% sarcosine, 25 mM sodium citrate, 0.7% β-mercaptoethanol). This isolation procedure is based on the guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction method described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (12). We modified it to include a second extraction. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min, the RNA in the aqueous phase was precipitated by isopropanol. RNA precipitates were dissolved in 1 ml of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.5]) and extracted a second time. The precipitates were then washed once in 75% ethanol and resuspended in 200 μl of 0.2% diethyl pyrocarbonate in water. Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated by first heating a mixture containing 250 μg of RNA in 450 μl of a solution containing 360 μl of 0.1% diethyl pyrocarbonate water, 75 μl of binding buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, 6 mM EDTA, 3 M NaCl [pH 7.5]), and 15 μl of polystyrene latex Oligotex-dT beads (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.) to 65°C for 5 min. Thereafter, the suspension was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and the Oligotex-dT beads were washed in TE buffer. Poly(A)+ RNA was eluted at 80°C from the polystyrene latex-oligo(dT) beads with elution buffer (5 mM Tris [pH 7.5]). Poly(A)+ RNA was quantitated for each sample by using multiple dilutions applied to DNA Dipsticks (Invitrogen).

Reverse transcriptase-mediated PCR (RT-PCR) for detection of cytokine mRNA.

To determine whether a particular cytokine mRNA was expressed, 300 ng of poly(A)+ RNA, isolated as described above from murine spleens stimulated with MAN, was reverse transcribed in the buffer supplied by the manufacturer in the presence of random hexamer with 200 to 400 U of SuperScript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase or Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The reaction was carried out at room temperature for 30 min, followed by 90 min at 37°C. The reverse transcriptase was inactivated at 95°C for 5 min, and the cDNA was precipitated in ethanol. After the precipitate was washed in 75% ethanol, 15% of the reverse-transcribed RNA, the equivalent of 40 ng of input RNA, was used in PCR for the detection of each cytokine gene in question or for the detection of the housekeeping gene G3PDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). The amplification reaction included combining the cDNA with 1.25 U of Taq polymerase, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 μg of each primer, 2 to 3 mM MgCl2, and PCR buffer (Gibco BRL). Positive (concanavalin A-stimulated splenocyte extracts) and negative (water) controls were included in each assay. Reactions were assembled with positive-displacement pipettes and brought to 65°C prior to the addition of Taq polymerase. Each 50-μl sample was overlaid with 75 μl of mineral oil (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and placed in a thermal cycler (Robocycler 40 [Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.] or Apolitron I [Thermolyne, Dubuque, Iowa]) with temperatures of 95°C for denaturation, 58°C for annealing, and 72°C for extension, with the first 3 of 35 total cycles having extended denaturation and annealing times. Various numbers of cycles for each cytokine were compared in early experiments, and 35 was in the linear range for all cytokines tested. Primers were synthesized by the Midland Certified Reagent Company (Midland, Tex.) according to sequences selected by one of the authors. The sequences of 5′ sense primers and 3′ antisense primers used in this study and their amplified fragment DNA sizes are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Cytokine primer sequences and amplified fragment sizes

| Cytokine | Primer sequence | Amplified fragment size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | ||

| Sense | 5′-AAC TCA AGT GGC ATA GAT GTG GA | 321 |

| Antisense | 5′-TCC TTT TCC GCT TCC TGA GGC TTG | |

| IL-2 | ||

| Sense | 5′-GAC ACT TGT GCT CCT TGT CAA CAG | 329 |

| Antisense | 5′-TGA TGA AAT TCT CAG CAT CTT CCA | |

| IL-4 | ||

| Sense | 5′-TCT CTA GAT CAT CGG CAT TTT GAA CGA GGT C | 306 |

| Antisense | 5′-TGC ATG ATG CTC TTT AGG CTT TCC | |

| IL-10 | ||

| Sense | 5′-GGA CAA CAT ACT GCT AAC CGA CTC | 257 |

| Antisense | 5′-AAA ATC ACT CTT CAC CTG CTC CAC | |

| IL-12p40 | ||

| Sense | 5′-CCA CTC ACA TCT GCT GCT CCA CAA G | 266 |

| Antisense | 5′-ACT TCT CAT AGT CCC TTT GGT CCA G | |

| G3PDH | ||

| Sense | 5′-CCA TCA CCA TCT TCC AGG AGC GAG | 345 |

| Antisense | 5′-CAC AGT CTT CTG GGT GGC AGT GAT |

Quantitation of IL-12p40 mRNA.

Initially the relative quantities of all cytokines were determined visually from photographs of the gels. All poly(A)+ samples from a given experiment representing each of the time intervals tested were subjected to RT-PCR for a specific cytokine mRNA at the same time, using the same percentage of input cDNA; i.e., each reaction was begun transcribing 300 ng of mRNA, and 15% of each transcribed mixture was subjected to PCR and then electrophoresed in the same gel or in two gels placed in the same chamber at the same time. Photographs of the gels were then evaluated independently by three individuals, and the intensity of bands was rated on a scale of 0 to +3. The mean ± standard error of the mean could then be determined by combining the data from all animals. IL-12 was selected for more accurate quantification by quantitative competitive RT-PCR (QC-RT-PCR). Specifically, the amount of IL-12p40 mRNA expressed in a particular sample was determined by the method of Bost and Clements (6) except that the actual quantification was performed by densitometry rather than radiolabeling. Competitor DNA, similar to but demonstrably different in size from IL-12p40 cDNA, but which could be amplified by the same pair of primers, was produced by RT-PCR amplification of plasmid DNA.

For QC-RT-PCR, various dilutions of the IL-12p40 competitor DNA (34 to 25,000 fg) were added to individual tubes, each containing the same amount of cDNA from a particular sample. PCR was carried out as described above with the IL-12p40 primer pair that amplified a 266-bp IL-12p40 fragment. The IL-12p40 competitor, with its 78-bp deletion, amplified a 188-bp IL-12p40 fragment. After PCR, 30% of each reaction mixture was electrophoresed on 2% agarose ethidium bromide-stained gels, the amplified fragments were captured on film, and quantitation was accomplished with an Ultra Scan XL densitometer (Pharmacia LKB, Piscataway, N.J.).

Quantitation of secreted IL-12p40 and IL-12p70.

Secretion of IL-12p40 into sera was quantified by a capture ELISA as described previously (35). The monoclonal antibody C15.6, which recognizes monomeric or dimeric IL-12p40, was used to coat microtiter plates, and the IL-12p40 captured by this monoclonal antibody was detected by using the biotinylated monoclonal antibody with specificity for a different determinant of IL-12p40, C17.8. A hybridoma secreting the monoclonal antibody C15.6 was kindly provided by G. Trinchieri (Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, Pa.), and the biotinylated antibody produced by C17.8 was purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.). The sensitivity of this assay was determined to be approximately 10 pg of IL-12p40 per ml.

For detection of IL-12p70, a mixture of two monoclonal antibodies which recognize IL-12p35 (Red-T and G297-289; PharMingen) was used to coat microtiter plates. Following incubation with sera and washing to remove any unbound IL-12, biotinylated anti-IL-12p40 monoclonal antibody C17.8 (PharMingen) was added to detect bound molecules containing both p35 and p40 subunits. ELISA reagents used to detect IL-12p70 could not recognize monomeric or dimeric IL-12p40. The sensitivity of this ELISA was approximately 30 pg of IL-12p70 per ml.

Standard curves were developed by using recombinant IL-12p40 and recombinant IL-12p70 (PharMingen) in the above-described assays, and the quantities of each in the test sera were determined by comparison with the standard curves. No attempts were made to distinguish between the quantities of monomeric and dimeric IL-12p40.

Preparation of monoclonal anti-IL-4.

Anti-IL-4 antibody was harvested from ascites following intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 5 × 106 cultured 11B11 hybridoma cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) into nude mice 10 days after i.p. injection of 0.5 ml pristane (Sigma). The induced ascites were collected beginning at day 10, and purified immunoglobulins were extracted by using a protein A affinity column (Bio-Rad Chemical Division, Richmond, Calif.). The procedures outlined by the manufacturer of the column were followed. Protein was estimated in the purified immunoglobulin preparations by absorbance readings at 280 nm, and mice were treated with the antibodies, based on micrograms of protein per milliliter. Each mouse received 200 to 400 μg of protein/dose i.p. These doses were selected empirically, using as a guideline doses used successfully by others (42, 54, 59).

To determine whether the anti-IL-4 prepared as described above could neutralize IL-4 secreted by the murine cells, IL-4-specific enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays were performed as previously described in detail (40) except that various amounts of anti-IL-4 were incorporated in the medium at a time when the cells would be expected to be secreting cytokine in vitro. Anti-IL-4 was tested at concentrations of 0 to 100 μg of protein/well and rat immunoglobulin at a concentration of 10 μg protein/well.

Immunization of mice and measurement of MAN-specific DH.

Mice were immunized by the cutaneous inoculation of 106 viable C. albicans on two occasions 2 weeks apart as described previously (28). Animals immunized in this manner develop maximum levels of DH 1 week following the second candidal challenge (19). DH was measured as previously described following the injection of 20 μl of NPS containing 30 μg of MAN into the footpads of mice (18). The footpads were premeasured with calipers and then measured again at 15 min and at 4 and 24 h after the injection of antigen. Since DH in the mouse peaks 24 h after the injection of antigen (reviewed in reference 14), data are reported for that time point.

Statistics.

Group sizes for in vivo studies of DH ranged from 6 to 8. The data were analyzed by using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

RESULTS

Cytokine mRNA expressed by splenocytes in mice stimulated with MAN.

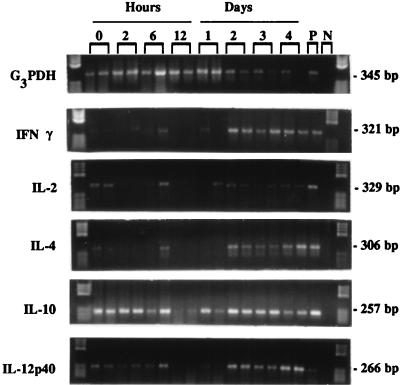

We had shown previously that the injection of MAN i.v. into mice stimulated the production of splenic CD8+ effector cells, which downregulated DH when transferred to immunized mice (24). Functional CD8+ cells were not present in transfer suspensions until 2 to 4 days after the injection of MAN (24), and CD4+ and I-A+ cells were required during the first 30 h after the injection of MAN for the induction of the CD8+ cells (39). Therefore, to obtain evidence of cytokine involvement during the induction of this regulatory phenomenon, splenocytes were tested for cytokine mRNA at selected intervals beginning at 2 h and continuing through 96 h after the introduction of MAN. As the experiments summarized below and in Fig. 1 were viewed as surveys designed to identify major changes in cytokine synthesis over time, and since a densitometer was not available to us at the time these analyses were done, it was felt that crude visual examinations would provide the data required for more in-depth studies to follow.

FIG. 1.

Composite photograph of RT-PCR products detected with cytokine or housekeeping gene-specific probes, using splenocytes of mice taken at various intervals following the injection of saline or 500 μg of C. albicans mannan i.v. P, positive control, splenocytes stimulated with concanavalin A; N, negative control. The negative control lane and the molecular weight marker lane are reversed on the IFN-γ strip. Molecular weight markers were placed at each side of the gel.

A composite photograph showing gels obtained following RT-PCR for each of the cytokines and for the housekeeping gene G3PDH from a single experiment is presented in Fig. 1. Each lane represents the product from a single mouse, and the products from two mice per observation period are shown. The same mRNA preparation was used for the entire panel of cytokine assays. In addition, the positive and negative controls carried through the RT-PCR procedure at the same time as the experimental samples are shown at the far right. The negative control for IFN-γ was mistakenly placed to the far right of the molecular weight standards when that specific gel was run. This same type of analysis was performed in two additional experiments. An analysis of the three experiments led us to conclude the following.

IL-2 message, while strong in the concanavalin A control, was not strong in any of the experimental samples, and its presence did not follow any distinct pattern. To the contrary, while IFN-γ and IL-4 mRNAs were weak initially, there was considerable message present from 48 to 96 h. Data presented elsewhere wherein ELISPOT assays were performed are consistent with these observations (40). IL-10 message was strong at all intervals tested. Although in the experiment shown in Fig. 1, IL-10 mRNA was very weak at 12 h, that was the only experiment in which that observation was made. Moreover, in the experiment illustrated in Fig. 1, G3PDH appeared to be downregulated beginning at about 48 h. Although the transcripts for G3PDH did, indeed, appear to be less during that interval in several experiments, that observation was not made for every experiment and we did not explore it further to confirm or refute it. If MAN does stimulate a modulation in the synthesis of G3PDH, however, it would not be the first time that G3PDH mRNA synthesis was modified in response to the experimental conditions (58).

Of particular interest to us, however, were the observations with IL-12. There was a constitutive level of IL-12p40 mRNA expressed in control mice which was reduced to minimal or undetectable levels by 12 h but then returned to control values by 48 h. Since IL-12 is considered a major factor for the initiation of DH (62, 65), and since secreted IL-12p40 is a known antagonist of bioactive IL-12p70 (29, 33, 44), we decided to pursue a more stringent quantitative evaluation of IL-12p40 at both the mRNA and secretory levels, as well as of IL-12p70 at the secretory level.

Message for IL-12p40 was quantitated by QC-RT-PCR. Those data are shown in Fig. 2. Clearly, IL-12p40 levels were quite low during the 2- to 24-h interval and were significantly increased at 96 h. The observations are consistent with the data shown in Fig. 1. Perhaps the most interesting data, however, were those which resulted from the ELISAs designed to detect IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 in sera taken from mice at selected intervals following the i.v. administration of MAN (Table 2). There was no detectable IL-12p70 at any time point between 0 and 96 h following the administration of MAN. To the contrary, IL-12p40 was detected, beginning with small quantities at 12 h, which rose 22-fold by 48 h and then dropped to near 12-h levels by 96 h.

FIG. 2.

Quantitation, using QC-RT-PCR and a competitive inhibitor of IL-12p40, in splenocytes taken from mice at selected intervals following the i.v. injection of saline, represented on the figure as 0 h, or C. albicans mannan. The saline-injected animals were sacrificed along with the animals inoculated with MAN 2 h prior to sacrifice. The insert is a representative gel of the assay and shows the gel from which the 2-h MAN determination was made. The concentrations of competitor shown range from a high of 7,500 pg to a low of 10 pg.

TABLE 2.

Quantitation of IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 in serum at selected intervals following the i.v. administration of MAN to naive animals

| Time (h) after administration of MAN | Concn (pg/ml)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| IL-12p40 | IL-12p70 | |

| 0 | <10b | <30c |

| 2 | <10 | <30 |

| 6 | <10 | <30 |

| 12 | 14 ± 7 | <30 |

| 24 | 39 ± 9 | <30 |

| 48 | 307 ± 28 | <30 |

| 72 | 113 ± 19 | <30 |

| 96 | 29 ± 12 | <30 |

Mean ± standard error, triplicate determinations from two animals.

Lower limit for IL-12p40 assay.

Lower limit for IL-12p70 assay.

Partial abrogation of downregulatory activity in vivo by administration of anti-IL-4 to immunized and MAN-treated mice.

IL-4 was selected for additional study for the following reasons: (i) it was the cytokine for which the greatest increase in the number of spot-forming cells (SFC) was noted in MAN-treated mice during the induction of CD8+ effector cells (40), and (ii) IL-4 has been described as a cytokine required for the induction and elicitation of contact sensitivity (CS) (2, 60, 69). Therefore, if IL-4 is a critical cytokine for the expression of DH to MAN, it would be unlikely to play a role in downregulation, as suggested by the ELISPOT data.

Prior to performing in vivo experiments, however, it was necessary to verify that the anti-IL-4 preparation was capable of neutralizing IL-4. Therefore, two mice each were injected either with saline or MAN, their splenocytes were harvested 96 h later, and ELISPOT assays were initiated. Cells were diluted into 96-well plates and treated with the putative anti-IL-4 during culture. After incubation, IL-4-secreting SFC were detected and the percent decrease after treatment with anti-IL-4 was calculated. The data are summarized in Table 3. Clearly, anti-IL-4 added to the cell cultures neutralized IL-4 secreted by the cells; thus, greatly reduced numbers of SFC were detected in cultures incubated with anti-IL-4. Moreover, the reduction in the number of cells detected was concentration-dependent. When rat immunoglobulin G was used as a control in the system, there appeared to be some nonspecific blocking of the IL-4. However, anti-IL-4 blocked to a much greater extent.

TABLE 3.

Ability of rat monoclonal anti-IL-4 antibody (11B11) to neutralize IL-4 secreted by T-enriched splenocytes from mice treated i.v. with saline or MAN

| Source of immuno- globulin | Protein (μg/ml) | Saline treated

|

MAN treated

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 SFC/ 6 × 105 T-enriched splenocytes | % Inhi- bition | IL-4 SFC/ 6 × 105 T-enriched splenocytes | % Inhi- bition | ||

| 0 | 27.5 | 39.0 | |||

| 11B11 | 1 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 21.8 | |

| 11B11 | 10 | 10.0 | 63.6 | 19.5 | 50.0 |

| 11B11 | 100 | 1.0 | 96.4 | 6.5 | 83.3 |

| RIga | 10 | 25.0 | 9.1 | 25.0 | 16.7 |

RIg, rat immunoglobulin.

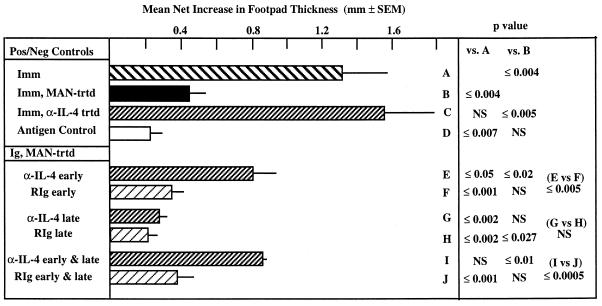

The anti-IL-4 was then used in vivo to determine its effect on the induction and/or expression of downregulatory activity in mice immunized with C. albicans and on immunized mice treated with MAN during the immunization procedure. The experimental design is shown in Table 4, and the data are presented in Fig. 3. The experiment shown was one of four in which similar observations were made. The animals in the experiment shown received a total of 2 mg (group C), 1,200 μg (groups E and F), or 800 μg (groups G and H) of protein of the anti-IL-4 preparation. Anti-IL-4 clearly had no effect on the expression of DH in immunized mice (Fig. 3, bar C) or on the expression of DH in immunized mice that had been administered MAN (bar G). To the contrary, there was a partial abrogation of the MAN-specific downregulation in mice given anti-IL-4 during the induction phase (bar E). DH responses in such mice were never as great as those in control immunized animals, however. Administration of anti-IL-4 at both the induction and expression stages had the same effect as the administration of anti-IL-4 at the induction phase only (bar I). Thus, these data suggest that IL-4 may be one, but not the only, factor involved in the induction of the MAN-specific downregulatory activity and that it is not involved in the expression of DH specific for MAN.

TABLE 4.

Experimental design for testing effect of anti-IL-4 in C. albicans-immunized and downregulated mice

| Phase and day | Treatment | Presence or absence in groupa:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | ||

| None (day 0) | Viable C. albicans | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Induction (early) | |||||||||||

| 12 | Immunoglobulin | − | − | + (MAb) | − | + (MAb) | + (RIg) | − | − | + (MAb) | + (RIg) |

| 13 | Mannan | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 14 | Viable C. albicans | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Immunoglobulin | − | − | + (MAb) | − | + (MAb) | + (RIg) | − | − | + (MAb) | + (RIg) | |

| 16 | Immunoglobulin | − | − | + (MAb) | − | + (MAb) | + (RIg) | − | − | + (MAb) | + (RIg) |

| Expression (late) | |||||||||||

| 20 | Immunoglobulin | − | − | + (MAb) | − | − | − | + (MAb) | + (RIg) | + (MAb) | + (RIg) |

| 21 | Footpad test | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Immunoglobulin | − | − | + (MAb) | − | − | − | + (MAb) | + (RIg) | + (MAb) | + (RIg) | |

MAb, monoclonal antibody (11B11) specific for mouse IL-4; RIg, rat serum immunoglobulin.

FIG. 3.

DH in control and immunized mice, some of which were treated during the induction and/or expression phases with NPS, MAN, and/or monoclonal anti-IL-4 antibody or rat serum immunoglobulin (Table 4). In the experiment shown, animals treated during both the induction and expression phases received a total of 2 mg of protein of the anti-IL-4 preparation or rat immunoglobulin, those treated during only the induction phase received 1,200 μg of protein, and those treated during the expression phase received 700 μg of protein. NS, not significant. P values were determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

The argument can be made that only partial abrogation occurred because insufficient anti-IL-4 was administered to the mice. However, in the first of the four experiments performed, the quantity of antibody used was one-half of that used in the experiment described in Table 4, and the data obtained with the lower dose were essentially the same as those with the higher dose. For example, immunized and MAN-treated mice given anti-IL-4 during the induction phase had an average footpad reading of 0.74 ± 0.06 mm (mean ± standard error of the mean), whereas immunized or immunized and MAN-treated mice, none of which were treated with anti-IL-4, had average values of 1.53 ± 0.10 and 0.11 ± 0.06, respectively. Thus, doubling the amount of anti-IL-4 administered did not alter the relative changes in DH observed with the lower concentration.

DISCUSSION

The most interesting observations made here over the 96-h observation period following the administration of MAN include (i) a reduction in mRNA synthesis for IL-12p40 within the first 2 h and continuing through 24 h, (ii) secretion of IL-12p40, beginning with levels barely detectable at 12 h, peaking at 48 h, and returning to barely detectable at 96 h, (iii) complete lack of secretion of IL-12p70 at any time after the administration of MAN, (iv) little or no apparent synthesis of mRNA specific for IFN-γ and IL-4 for the first 48 h but obvious production thereafter, and (v) synthesis of IL-10 mRNA throughout the entire period. In addition, partial abrogation of downregulatory activity was affected by the administration of anti-IL-4 to immunized animals during the induction phase of the downregulatory activity.

IL-12 is a 70-kDa heterodimeric cytokine composed of covalently linked 35-kDa (p35) and 40-kDa (p40) subunits whose activity was first described by Kobayashi et al. (36). It is produced predominantly by macrophages and B cells (10, 15), and it is generally believed to link the innate and acquired immune systems (reviewed in reference 65). IL-12 induces the production of several cytokines, including IFN-γ and IL-2 (66, 70), from T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells in vitro as well as in vivo (26). Moreover, IL-12 induces the differentiation of Th1 cells from naive T cells (Th0) (34), thus initiating cell-mediated immunity. It regulates the proliferation of not only Th1 cells (34) but also cytotoxic T lymphocytes (66). This cytokine, therefore, represents an important regulatory bridge between innate resistance and adoptive immunity (65).

Since only IL-12p40, and not IL-12p70, the former of which is a known antagonist of IL-12 bioactivity (29, 33, 44), was secreted following the introduction of MAN into naive animals, there was never the opportunity for DH to be initiated. However, the phenomenon observed here is not simply a lack of initiation of DH, in that MAN-specific downregulatory cells that can function to inhibit an established DH response are also produced (24). Thus, it is likely that other cytokines, for example, IL-4 and/or IL-10, play a role during the inductive phase. While we have no evidence at this time with regard to IL-10, we have shown that IL-4-secreting cells were increased in elevated numbers beginning at about 24 h following the introduction of MAN (40) and that the administration of anti-IL-4 to immunized MAN-treated mice partially abrogated the downregulatory activity. Moreover, even if some bioactive IL-12 was produced but remained undetected in the MAN-treated animals, it has been reported in other systems that IL-4 takes precedence over IL-12 when the two cytokines are present at the same time (34, 64, 66).

IL-10 is as interesting as IL-12 with regard to regulation of cell-mediated immunity, however. IL-10 was originally described as a factor which prevented the proliferation of Th1 cell clones by inhibiting IFN-γ and IL-2 production (21, 22). Subsequently, Fiorentino et al. (23) demonstrated that IL-10 acted on antigen-presenting cells to inhibit cytokine synthesis. IL-10, in fact, has been shown to have many different functions (reviewed in reference 46), some of which are stimulatory (11, 41) and some of which are inhibitory (17, 20, 38, 67, 71). The precise role of IL-10 in this MAN-specific system is unknown at this time, since we have not yet had an opportunity to investigate the secretion of IL-10 after MAN administration or the effects of ablation of IL-10 activity in vivo.

The data presented here, as well as those in another study from our laboratory (40), are not consistent with the hypothesis that IL-4 is a critical cytokine in the initiation and elicitation of DH to MAN, such as has been proposed for CS to chemicals. CS is considered one manifestation of cellular immunity, specifically DH, and two groups of investigators have proposed that IL-4 is critical for both its induction (60) and elicitation (69). There are conflicting data (27), however. Weigmann et al. (69) speculated that these seemingly contradictory activities of IL-4 could be explained on the basis of concentration of IL-4; higher concentrations were inhibitory and lower concentrations were enhancing. The data obtained, therefore, would depend on the efficiency with which IL-4 was removed or inhibited in vivo. We have collected no additional data at this time that would allow us to state unequivocally how IL-4 and other factors contribute to the induction of MAN-specific downregulation in murine candidiasis. Reports of inhibition of cell-mediated immunity and reactive nitrogen oxide induced by IL-4, IL-10, and transforming growth factor β in parasitic infections (63), along with data showing the inhibition of both candidacidal activity and nitric oxide production in IFN-γ-activated macrophages by IL-4 and/or IL-10 (9), may provide clues for future investigations of the mechanism of action of cytokines in MAN-induced suppression.

Several laboratories have been investigating additional relationships between various cytokines and C. albicans (55–57) or C. albicans MAN (3). IL-12 production has been shown to correlate with the induction of Th1 type responses in murine candidiasis, and the neutralization of IL-12 by administration of anti-IL-12 antibody abrogates resistance to C. albicans (55–57). Using human cells in vitro, Ausiello et al. (3) determined that mannoprotein did not consistently stimulate the expression of IL-1, IL-5, and IL-10 but did induce long-lasting production of mRNAs for IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-6, along with appreciable levels of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IFN-γ, and IL-2. The stimulation of human cells in vitro appears to be quite different from the stimulation of murine cells in vivo, particularly with respect to the stimulation of IFN-γ and IL-2, as evidenced from both the mRNA studies here and the ELISPOT data presented elsewhere (40).

The inability or reduced ability to respond to a normally immunogenic preparation of an antigen has been a highly controversial area over the past decade, and the validity of the terms suppression and suppressor cell have been debated with considerable fervor (30). Despite the debate, there is no question that the phenomenon occurs; it has been demonstrated in fungal models by us (8, 18) and others (5, 13, 16, 32, 49), in bacterial and parasitic systems (reviewed in reference 68), and in systems involving CS (reviewed in reference 1). There has been something of a renewed interest in suppressive phenomena; IL-10 production by autoreactive CD8+ T-cell clones has been described (31), and IL-10 epitopes (43) have been associated with antigen-specific T suppressor cells. Moreover, Nanda et al. (50) have described a unique pattern of lymphokine synthesis involving the cosynthesis of IL-10 and IFN-γ in selected antigen-specific suppressor T-cell clones. IFN-γ message was not upregulated during the induction phase of suppression in the MAN-specific model, i.e., ≤48 h after the injection of MAN, but it was thereafter. Finally, Buchanan and Murphy (7) reported increased production of IL-5 in suppressed mice, with decreased production of IFN-γ and IL-2. IL-4 was unchanged.

The role of these downregulatory cells in protective immunity in experimental candidiasis has been incompletely explored. It has been shown that when downregulatory cells are induced in immunized animals, they have no effect on protective immunity when animals are challenged i.v. (25). Since there appears to be a dichotomy of protective mechanisms against C. albicans, however, with cellular immunity being critical against mucosal disease (4), downregulatory cells may well modulate protective immunity at that level. Investigations of immunoregulatory cell involvement in protection at the mucosal level await the development of a suitable animal model in which to demonstrate it.

In summary, our data are suggestive of a role for IL-4, acting in the absence of bioactive IL-12 and presence of potentially antagonistic IL-12p40, in the induction and maintenance of MAN-specific T-cell suppression. Perhaps IL-10 contributes to the induction of the CD8+ effector cells as well, but since only message, and not secretion, was measured for that cytokine, there are no data to support that hypothesis. As a next step, however, it would be appropriate to determine whether in vivo treatment with IL-12 or with anti-IL-10 prevents the induction of the MAN-specific immunomodulatory cells. The most definite experiments will likely involve knockout mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This investigation was supported by Public Health Service grants AI-12806 (J.E.D.), AI-12913 (S.A.M.), and AI-32976 (K.L.B.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asherson G L, Colizzi M, Zembala M. An overview of T-suppressor cell circuits. Annu Rev Immunol. 1986;4:37–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.04.040186.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asherson G L, Dieli F, Sireci G, Salerno A. Role of IL-4 in delayed type hypersensitivity. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.845537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausiello C, Urbani F, Gessani S, Spagnoli G C, Gomez M J, Cassone A. Cytokine gene expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated by mannoprotein constituents from Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4105–4111. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4105-4111.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balish E, Filutowicz H, Oberley R D. Correlates of cell-mediated immunity in Candida albicans-colonized gnotobiotic mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:107–113. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.107-113.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackstock R J, McCormack M, Hall N K. Induction of macrophage-suppressive lymphokine by soluble crytococcal antigens and its association with models of immunologic tolerance. Infect Immun. 1987;55:233–239. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.233-239.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bost K L, Clements J D. In vivo induction of interleukin-12 mRNA expression after oral immunization with Salmonella dublin or the B subunit of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1076–1083. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1076-1083.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchanan R L, Murphy J W. Regulation of cytokine production during the expression phase of the anticryptococcal delayed-type hypersensitivity response. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2930–2939. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2930-2939.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrow E W, Domer J E. Immunoregulation in experimental murine candidiasis: specific suppression induced by Candida albicans cell wall glycoprotein. Infect Immun. 1985;49:171–181. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.1.172-181.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cenci E, Romani L, Mencacci A, Spaccapelo R, Schiaffella E, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 inhibit nitric oxide-dependent macrophage killing of Candida albicans. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1034–1038. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan S H, Perussia B, Gupta J W, Kobayashi M, Pospisil M, Young H A, Wolf S F, Young D, Clark S C, Trinchieri G. Induction of interferon γ production by natural killer cell stimulatory factor: characterization of the responder cells and synergy with other inducers. J Exp Med. 1991;173:869–879. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W F, Zlotnik A. IL-10: a novel cytotoxic T cell differentiation factor. J Immunol. 1991;147:528–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox R A, Kennell W. Suppression of T-lymphocyte response by Coccidioides immitis antigen. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1424–1429. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.6.1424-1429.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowle A J. Delayed hypersensitivity in the mouse. Adv Immunol. 1975;20:197–264. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Andrea A, Rengaraju M, Valiante N M, Chehimi J, Kubin M, Aste M, Chan S H, Kobayashi M, Young D, Nickbarg E, Chizzonite R, Wolf S F, Trinchieri G. Production of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (interleukin-12) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1387–1398. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deepe G S, Jr, Watson S R, Bullock W E. Cellular origins and target cells of immunoregulatory factors in mice with disseminated histoplasmosis. J Immunol. 1984;132:2064–2071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Prete G, De Carli M, Almerigogna F, Giudizi M G, Biagiotti R, Romagnani S. Human IL-10 is produced by both type 1 helper (Th1) and type 2 helper (Th2) T cell clones and inhibits their antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine production. J Immunol. 1993;150:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Domer J E, Garner R E, Befidi-Mengue R N. Mannan as an antigen in cell-mediated immunity (CMI) assays and as a modulator of mannan-specific CMI. Infect Immun. 1989;57:693–700. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.693-700.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domer J E, Moser S A. Experimental murine candidiasis: cell-mediated immunity after cutaneous challenge. Infect Immun. 1978;20:88–98. doi: 10.1128/iai.20.1.88-98.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enk A H, Angeloni V L, Udey M C, Katz S I. Inhibition of Langerhans cell antigen-presenting function by IL-10. A role for IL-10 in induction of tolerance. J Immunol. 1993;151:2390–2398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez-Botran R, Sanders V M, Mosmann T R, Vitetta E S. Lymphokine-mediated regulation of the proliferative response of clones of T helper 1 and T helper 2 cells. J Exp Med. 1988;168:543–558. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.2.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiorentino D F, Bond M W, Mosmann T R. Two types of mouse helper T cell. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2081–2095. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiorentino D F, Zlotnik A, Mosmann T R, Howard M, O’Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garner R E, Childress A M, Human L G, Domer J E. Characterization of Candida albicans mannan-induced, mannan-specific delayed hypersensitivity suppressor cells. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2613–2620. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2613-2620.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garner R E, Domer J E. Lack of effect of Candida albicans mannan on development of protective immune responses in experimental murine candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:738–741. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.738-741.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gately M K, Warrier R R, Honasoge S, Carvajal D M, Faherty D A, Connaughton S E, Anderson T D, Sarmiento U, Hubbard B R, Murphy M. Administration of recombinant IL-12 to normal mice enhances cytolytic lymphocyte activity and induces production of IFN-γ in vivo. Int Immunol. 1994;6:157–167. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gautam S C, Chikkala N F, Hamilton T A. Anti-inflammatory action of IL-4. J Immunol. 1992;148:1411–1415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giger D K, Domer J E, McQuitty J T. Experimental murine candidiasis: pathologic and immune responses to cutaneous inoculation with Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1978;19:499–509. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.2.499-509.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillessen S, Carvajal D, Ling P, Podlaski F J, Stremlo D L, Familletti P C, Gubler U, Presby D H, Stern A S, Gately M K. Mouse interleukin-12 (IL-12) p40 homodimer: a potent IL-12 antagonist. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:200–206. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green D R, Webb D R. Saying the “S” word in public. Immunol Today. 1993;14:523–525. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90180-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hisatsune T, Nishijima K-I, Minai Y, Kohyama M, Kaminogawa S. Autoreactive CD8+ T cell clones producing immune suppressive lymphokines IL-10 and interferon-γ. Cell Immunol. 1994;154:181–192. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ibrahim A B, Pappagianis D. Experimental induction of anergy to coccidioidin by antigens of Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 1973;7:786–794. doi: 10.1128/iai.7.5.786-794.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato K, Shimozato O, Hoshi K, Wakimoto H, Hamada H, Yagita H, Okumura K. Local production of the p40 subunit of interleukin 12 suppresses allogeneic myoblast rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9085–9089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy M K, Picha K S, Shanebeck K D, Anderson D M, Brabstein K H. Interleukin-12 regulates the proliferation of Th1, but not Th2 or Th0, clones. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2271–2278. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kincy-Cain T, Bost K L. Substance P-induced IL-12 production by murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;158:2334–2339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi M, Fitz L, Ryan M, Hewick R M, Clark S C, Chan S, Loudon R, Sherman F, Perussia B, Trinchieri G. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biological effects on human lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170:827–846. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kocourek J, Ballou C E. Method for fingerprinting yeast cell wall mannans. J Bacteriol. 1969;100:1175–1181. doi: 10.1128/jb.100.3.1175-1181.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Elliott J F, Mosmann T R. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production, vascular leakage, and swelling during T helper 1 cell-induced delayed-type hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 1994;153:3967–3978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li S P, Lee S, Wang Y, Domer J E. Candida albicans mannan-specific, delayed hypersensitivity down-regulatory CD8+ cells are genetically restricted effectors and their production requires CD4 and I-A expression. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1996;109:334–343. doi: 10.1159/000237260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S P, Lee S-I, Domer J E. Alterations in frequency of interleukin (IL-2)-, gamma interferon-, or IL-4-secreting splenocytes induced by Candida albicans mannan and/or monophosphoryl lipid A. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1392–1399. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1392-1399.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacNeil I A, Suda T, Moore K W, Mosmann T R, Zlotnik A. IL-10, a novel growth cofactor for mature and immature T. cells. J Immunol. 1990;145:4167–4173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magee D M, Cox R A. Roles of gamma interferon and interleukin-4 in genetically determined resistance to Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3514–3519. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3514-3519.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malley A, Zeleny-Pooley M, Murray G. Stabilization and characterization of antigen-specific T suppressor inducer and T suppressor effector molecules. J Immunol Methods. 1995;178:31–39. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00237-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattner F, Fischer S, Guckes S, Jin S, Kaulen H, Schmitt E, Rude E, Germann T. The interleukin-12 subunit p40 specifically inhibits effects of the interleukin-12 heterodimer. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2202–2208. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKnight A J, Zimmer G J, Fogelman I, Wolf S F, Abbas A K. Effects of IL-12 on helper T cell-dependent immune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 1994;152:2172–2179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore K W, O’Garra A, Malefyt R W, Vieira P, Mosmann T R. Interleukin-10. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosmann T R, Cherwinski H, Bond M W, Giedlin M A, Coffman R L. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136:2348–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy J W, Moorhead J W. Regulation of cell-mediated immunity in cryptococcosis I. Induction of specific afferent T suppressor cells by cryptococcal antigen. J Immunol. 1982;128:276–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nanda N K, Sercarz E E, Hsu D-H, Kronenberg M. A unique pattern of lymphokine synthesis is a characteristic of certain antigen-specific suppressor T cell clones. Int Immunol. 1994;6:731–737. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peat S, Whelan W J, Edwards T E. Polysaccharide of baker’s yeast. Part IV. Mannan. J Chem Soc (London) 1961;1:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rivas J M, Ullrich S E. Systemic suppression of delayed-type hypersensitivity by supernatants from UV-irradiated keratinocytes: an essential role for keratinocyte-derived IL-10. J Immunol. 1992;149:3865–3871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rivas J M, Ullrich S E. The role of IL-4, IL-10, and TNF-α in the immune suppression induced by ultraviolet radiation. J Leukocyte Biol. 1994;56:769–775. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.6.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Romani L, Mencacci A, Grohmann U, Mocci S, Mosci P, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Neutralizing antibody to interleukin 4 induces systemic protection and T helper type 1-associated immunity in murine candidiasis. J Exp Med. 1992;176:19–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Romani L, Mencacci A, Tonnetti L, Spaccapelo R, Cenci E, Wolf S, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Interleukin-12 but not interferon-γ production correlates with induction of T helper type-1 phenotype in murine candidiasis. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:909–915. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romani L, Mencacci A, Tonnetti L, Spaccapelo R, Cenci E, Puccetti P, Wolf S F, Bistoni F. IL-12 is both required and prognostic in vivo for T helper type 1 differentiation in murine candidiasis. J Immunol. 1994;152:5167–5175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Romani L, Mocci S, Bietta C, Lanfaloni L, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Th1 and Th2 cytokine secretion patterns in murine candidiasis: association of Th1 responses with acquired resistance. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4647–4654. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4647-4654.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sabath D E, Broome H E, Prystowsky M B. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA is a major interleukin 2-induced transcript in a cloned T-helper lymphocyte. Gene. 1990;91:185–191. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sadick M D, Heinzel F P, Holaday B J, Pu R T, Dawkins R S, Locksley R M. Cure of murine leishmaniasis with anti-interleukin 4 monoclonal antibody. Evidence for a T cell-dependent, interferon γ-independent mechanism. J Exp Med. 1990;171:115–127. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salerno A, Dieli F, Sireci G, Bellavia A, Asherson G L. Interleukin-4 is a critical cytokine in contact sensitivity. Immunology. 1995;84:404–409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmitt E, Owen-Schaub L, Ullrich S E. Effect of IL-12 on immune suppression and suppressor cell induction by ultraviolet radiation. J Immunol. 1995;154:5114–5120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott P. IL-12: initiation cytokine for cell-mediated immunity. Science. 1993;260:496–497. doi: 10.1126/science.8097337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sher A, Gazzinelli R T, Oswald I P, Clerici M, Kullberg M, Pearce E J, Berzofsky J A, Mosmann T R, James S L, Morse III H C, Shearer G M. Role of T-cell derived cytokines in the downregulation of immune responses in parasitic and retroviral infection. Immunol Rev. 1992;127:183–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szabo S J, Jacobson N G, Dighe A S, Gubler U, Murphy K M. Developmental commitment to the Th2 lineage by extinction of IL-12 signaling. Immunity. 1995;2:665–675. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a cytokine produced by antigen-presenting cells with immunoregulatory functions in the generation of T-helper cells type 1 and cytotoxic lymphocytes. Blood. 1994;84:4008–4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ullrich S E. Mechanism involved in the systemic suppression of antigen-presenting cell function by UV radiation: keratinocyte-derived IL-10 modulates antigen-presenting cell function of splenic adherent cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:3410–3416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Webb D R, Kraig E, Devens B H. Suppressor cells and immunity in mechanisms of immune regulation. Chem Immunol. 1994;58:146–192. doi: 10.1159/000319224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weigmann B, Schwing J, Huber H, Ross R, Mossmann H, Knop J, Reske-Kunz A B. Diminished contact hypersensitivity response in IL-4 deficient mice at a late phase of the elicitation reaction. Scand J Immunol. 1997;45:308–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wolf S F, Sieburth D, Sypek J. Interleukin 12: a key modulator of immune function. Stem Cells. 1994;12:154–168. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530120203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu J, Cunha R Q, Liew R Y, Weiser W Y. IL-10 inhibits the synthesis of migration inhibitory factor and migration inhibitory factor-mediated macrophage activation. J Immunol. 1993;151:4325–4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]