Abstract

Objectives

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease that can result in high morbidity if not treated. This retrospective study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of rituximab treatment in a paediatric SLE cohort in Taiwan.

Methods

The medical records of paediatric patients diagnosed with SLE at the National Taiwan University Hospital between January 1992 and August 2022 who received rituximab as maintenance therapy between January 2015 and August 2022 were retrospectively reviewed. To enhance our analysis, we included a contemporary comparison group, matching in case number and demographic characteristics. This study aimed to describe the indications, efficacy and safety of rituximab in the treatment of paediatric SLE and to analyse the factors associated with disease outcomes.

Results

The study included 40 rituximab-treated patients with a median age of 14.3 years at the time of disease diagnosis. In the rituximab-treated cohort, the median score on the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 decreased from 8 before rituximab administration to 4 after 2 years. The levels of C3 and C4 increased and anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) levels decreased significantly within 6 months. The equivalent oral prednisolone dose halved after 6 months. Finally, 8 (20%) patients achieved disease control and 35 (87.5%) patients had no flare-ups during the follow-up period (median, 2 years). Those patients who achieved disease control had a significantly shorter interval between diagnosis and rituximab administration. In terms of adverse effects, only one patient developed hypogammaglobulinaemia that required intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement. Compared with the comparison group (n=53), the rituximab-treated cohort exhibited superior disease outcomes and a reduced incidence of flare-ups.

Conclusions

This study provides real-world data and illuminates rituximab’s role in maintaining disease stability among patients with paediatric-onset SLE who are serologically active without major clinical deterioration. Most importantly, no mortality or development of end-stage renal disease was observed in the rituximab-treated cohort.

Keywords: lupus erythematosus, systemic; autoimmune diseases; biological products

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

The efficacy and indications of rituximab in treating SLE are still debated, and only a few studies have focused on patients with paediatric-onset SLE who are serologically active without major clinical deterioration.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study enhances the understanding of the potential benefits of rituximab in paediatric SLE treatment.

The study contributes to the refinement of our therapeutic strategies aimed at managing these patients, particularly during phases of clinical stability.

In this retrospective cohort study that included 40 rituximab-treated patients, the score on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 decreased from 8 before rituximab administration to 4 after 2 years, and the equivalent oral prednisolone dose halved after 6 months significantly.

No mortality or development of end-stage renal disease was observed in our cohort.

Comparative analysis with a contemporary comparison group highlighted superior disease outcomes and a lower incidence of disease flare-ups in the rituximab-treated group.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study has illuminated rituximab’s role in maintaining disease stability among patients with paediatric-onset SLE who are serologically active without major clinical deterioration.

This intervention facilitates better disease control, enhances compliance, minimises side effects and demonstrates a steroid-sparing effect.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterised by multisystem involvement; the disease leads to significant morbidity if not treated.1 This disease is characterised by intermittent periods of flare-ups and occasional remission, with a substantial impact on patient health. Paediatric SLE is the second most prevalent paediatric rheumatic disease, followed by juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and is often more severe than SLE in adults.2 3 However, the use of corticosteroids to manage disease activity in children can lead to several adverse effects. Hence, finding alternative agents that can sustain disease stability over the long term and minimise the need for corticosteroids, coupled with good treatment adherence, would be a favourable option.

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that targets and depletes CD20-positive B cells.4 Because B cells play a central role in SLE pathophysiology, modulating memory or autoreactive B cell lines and striving for the reconstitution of a balanced B cell repertoire present a reasonable approach to managing the disease and achieving improved disease control, remission and sustained stability.5 Rituximab has been used in patients with SLE, particularly in those with refractory lupus nephritis or those who cannot tolerate other immunosuppressive agents.6–10 Moreover, several studies have suggested that rituximab may be an effective steroid-sparing agent for paediatric SLE.8 10–13 However, the use of rituximab as maintenance therapy for SLE is still relatively new, and paediatric data are limited. Most studies have used rituximab as rescue therapy, focusing on refractory disease, whereas only a few have evaluated rituximab as maintenance therapy.14

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of rituximab treatment in a paediatric SLE cohort in Taiwan, with a specific focus on the role of rituximab in maintaining disease activity. This study is of great importance as it provides real-world data on the use of rituximab in patients with paediatric SLE who are serologically active without major clinical deterioration and confirms its effectiveness as a steroid-sparing agent. This study also contributes to the current debate on the indications and efficacy of rituximab for SLE treatment.

Methods

Study design and enrolment criteria

This was a retrospective study. Eligible participants were patients diagnosed with paediatric SLE at the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH) between 1 January 1992 and 31 August 2022 who received at least one administration of rituximab between 1 January 2015 and 31 August 2022. All patients with paediatric SLE had disease onset before the age of 18 years and were diagnosed based on the criteria established by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics or European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR)/ACR classification.15–17 The follow-up period continued until 31 August 2022.

The study included patients who received rituximab as add-on maintenance therapy specifically for newly diagnosed paediatric SLE or serologically active SLE without major clinical deterioration. Serologically active SLE was defined as a Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score of 4, an elevated level of anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) or decreased levels of C3 or C4 within 1 year before the first dose of rituximab. Major clinical deterioration of SLE was defined as having an acute exacerbation, new-onset central nervous system (CNS) involvement, lupus nephritis or receiving steroid pulse therapy within 3 months before the first dose of rituximab. Patients who received rituximab for other indications were excluded.

Treatment protocol

The patients included in this study received rituximab as add-on maintenance therapy for SLE, administered at one dose of 375 mg/m2 (maximum 500 mg) at an interval of 6–12 months and delivered via slow intravenous infusion over 6–8 hours. Before rituximab administration, all patients were premedicated with methylprednisolone, antihistamines and acetaminophen. This was a retrospective study; therefore, there were no standardised treatment indications or schedules. Individual physicians made treatment decisions.

Data collection and assessments of response to rituximab

Data for this study were obtained by reviewing medical records. The records included relevant clinical characteristics such as sex, age at diagnosis, haemograms, B cell counts, IgG, complement (C3, C4), anti-dsDNA, renal function tests and SLEDAI-2K.18 Additionally, the type and dose of immunosuppressive therapy administered at the time of diagnosis were recorded. Clinical and laboratory parameters, medication usage, and SLEDAI-2K scores were monitored before rituximab treatment, 6 months post-treatment and annually thereafter until the last follow-up. Any adverse effects of rituximab such as allergic reactions, hypogammaglobulinaemia or infections due to its immune-modulating effects were recorded. Patients were screened for viral hepatitis before treatment, and liver function was monitored during the follow-up period.

Clinical remission was defined as a SLEDAI-2K score of 0 without immunosuppressants or corticosteroids.19 Disease control was defined as a SLEDAI-2K score of ≤2 with a prednisolone equivalent dose of ≤5 mg/day.20 The Safety of Estrogens in Lupus National Assessment (SELENA)-SLEDAI flare index21 was modified for this study, and flare-up was defined as occurring if any of the following criteria were met: (1) SLEDAI-2K increased to >12 points, (2) prednisolone increased to >0.5 mg/kg/day, (3) hospitalisation due to SLE flare-up, or (4) initiation of new cyclophosphamide, azathioprine or methotrexate. Patients who did not achieve clinical remission or disease control or experienced flare-ups during the follow-up period were categorised as having partial disease control.

Comparison group

We assembled a contemporary comparison group with a comparable case number, sex ratio, age at disease diagnosis and distribution of organ manifestations to the rituximab-treated group. This group comprised patients with paediatric SLE diagnosed at the NTUH between 1 January 2010 and 1 January 2020 who did not receive rituximab but were primarily managed with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) maintenance strategies. Data for this investigation were extracted through a thorough review of medical records. The follow-up duration extended up to 10 years, or until 31 August 2022 for cases with less than 10 years of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

All data were recorded and organised on a Microsoft Office Excel V.2021 worksheet. Results for categorical variables were reported as numbers (n) and percentages (%), while continuous variables were presented as medians with quartile ranges or means with SD. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used to analyse repeated measurements of clinical biomarkers. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare between-group categorical variables, while the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare between-group continuous variables. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted using Microsoft Office Excel V.2021 and GraphPad Prism V.9. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient population

In the rituximab-treated group, a total of 55 patients diagnosed with paediatric SLE and who received one or more administration of rituximab between 1 January 2015 and 31 August 2022 at the NTUH were identified. Patients who received rituximab for reasons other than maintenance therapy (n=15) were excluded. Of these, nine had acute exacerbations within 3 months, four received a dose every other week for autoimmune haemolytic anaemia and two had SLEDAI-2K scores of less than 4. Finally, 40 paediatric patients with SLE receiving rituximab as maintenance therapy were enrolled in this study as the rituximab-treated group and received 131 courses of rituximab. Among the 40 patients, 5 individuals were in the ‘newly diagnosed’ category. The rest, which were the majority, were classified as being in a state of ‘serologically active without major clinical deterioration’.

In addition, the comparison group comprising 53 patients with paediatric SLE, diagnosed between January 2010 and January 2020 at the NTUH and receiving DMARD maintenance strategies, was included for comparison in this retrospective study.

The demographics, laboratory data, SLE activity and steroid doses of the 40 enrolled rituximab-treated patients are summarised in table 1. The median age of the patients at the time of paediatric SLE diagnosis was 14.3 years (IQR 11.3–15.9), and 34 (85%) were women. On the occasion of rituximab administration, the cohort displayed a median age of 20.2 years (IQR 16.0–27.3) and had sustained a median duration of 6.8 years (IQR 2.4–12.3) since the initial diagnosis of SLE. The median follow-up period was 2.9 years (IQR 1.5–3.5). In the comparison group, the median age at paediatric SLE diagnosis was 14.0 years (IQR 11.8–15.6), of whom 48 (91%) were female. The median follow-up period was 10 years (IQR 7.5–10).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of enrolled rituximab-treated patients before the first dose of rituximab

| Number of patients | 40 | (131 RTX administrations) | |

| Men:women (%) | 6:34 | (0.18) | |

| Age at disease diagnosis, median (IQR) (range), years | 14.3 | (11.3–15.9) (4.6–17.9) | |

| Age (IQR) at first RTX use, median (IQR) (range), years | 20.2 | (16.0–27.3) (9.5–41.4) | |

| First RTX use age ≤18, n (%) patients | 17 | (42.5) | |

| First RTX use age >18, n (%) patients | 23 | (57.5) | |

| Interval from diagnosis to first RTX, median (IQR) (range), years | 6.8 | (2.4–12.3) (0.1–27.1) | |

| Duration of follow-up post-RTX, median (IQR) (range), years | 2.9 | (1.5–3.5) (0.1–7.3) | |

| Number of times of RTX administrations, mean (SD) (range) | 3.3 | (2.2) (1–7) | |

| Times of RTX use=1, n (%) patients | 13 | (32.5) | |

| Times of RTX use >1, n (%) patients | 27 | (67.5) | |

| Laboratory data, median (IQR) | Reference range | ||

| White cell count (x109/L) | 5.71 | (3.83–7.95) | 3.84–11.40 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 111 | (102–124) | 106–145 |

| Platelet (x109/L) | 274 | (212–318) | 175–369 |

| Lymphocyte count (x109/L) | 1.16 | (0.84–1.73) | NA |

| B cell (%) | 13 | (7–20) | 9–20 |

| B cell (x109/L) | 0.12 | (0.05–0.29) | NA |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 1866 | (1223–2750) | 700–1600 |

| C3 (mg/dL) | 62.5 | (44.7–77.1) | 87–200 |

| C4 (mg/dL) | 9.7 | (6.6–12.7) | 10–52 |

| Anti-dsDNA (IU/mL) | 662 | (337–1039) | Negative ≤200, equivocal 201–300, positive ≥301 |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 29 | (16–47) | 2–15 |

| Organ manifestations* at first RTX use, n (%) patients | |||

| Renal | 27 | (67.5) | |

| Haematological | 12 | (30) | |

| Musculoskeletal | 10 | (25) | |

| Neuropsychiatric | 1 | (2.5) | |

| Cardiopulmonary | 0 | (0) | |

| SLEDAI-2K, median (IQR) (range) | 8 | (6–12) (4–32) | |

| Steroid dose, median (IQR) (range), mg/kg/day | 0.2 | (0.2–0.8) (0–2) | |

*The definition of organ manifestations was based on the EULAR/ACR 2019 classification criteria.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; dsDNA, double stranded DNA; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EULAR, European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology; NA, not applicable; RTX, rituximab; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000.

Twenty-seven (67.5%) patients received more than one course of rituximab, with a mean of 4.3 courses in this subgroup. Patients who required only one dose of rituximab during the study period were presumably under disease control and therefore did not need further treatment; other factors, including personal and economic considerations and quarantine policies related to COVID-19, may have played a role. However, this was not specifically assessed in this study.

As shown in table 1, before rituximab treatment, elevated levels of IgG (median 1866 mg/dL), anti-dsDNA (median 662 IU/mL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (median 29 mm/hour), as well as decreased levels of C3 (median 62.5 mg/dL) and C4 (9.7 mg/dL), were found. These abnormal laboratory data were used as markers of SLE activity.22 23 The median SLEDAI-2K score before rituximab treatment was 8 (IQR 6–12). The kidneys (67.5%), haemogram (30%) and musculoskeletal system (25%) were the most commonly involved organs. Notably, the comparison group exhibited a comparable distribution of organ manifestations to the rituximab-treated group, with kidneys (67.9%), musculoskeletal (41.5%) and haematological system (39.6%) being the most commonly involved organs.

Rituximab use has increased over the past decade, as shown in figure 1A. The interval from the diagnosis of paediatric SLE to the first dose of rituximab shortened over time, as shown in figure 1B.

Figure 1.

(A) Year of rituximab use in patients’ first course and all courses, showing an increase in use over time. (B) The median interval of diagnosis of paediatric SLE to the first dose of rituximab (RTX) shows a decrease in interval over time. Data from January 2015 to August 2022.

Efficacy of rituximab

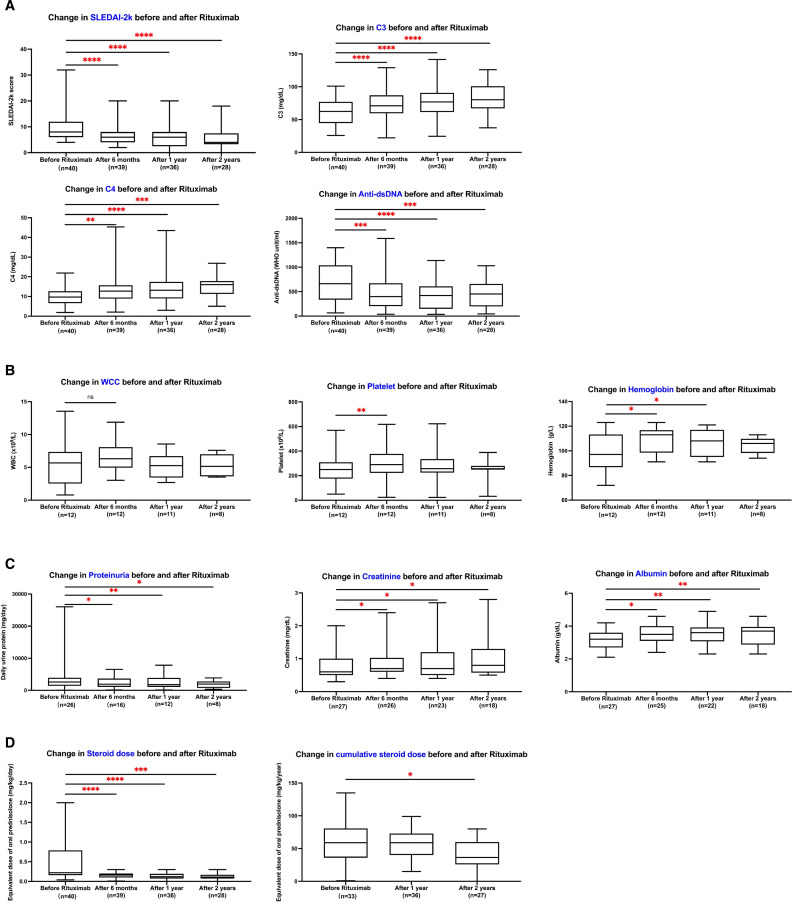

Disease activity, clinical biomarkers and corticosteroid doses measured before and after the first dose of rituximab at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years are summarised in figure 2. As shown in figure 2A, statistically significant improvements were observed in SLEDAI-2K, C3 and C4, and anti-dsDNA levels after rituximab administration. The median SLEDAI-2K score was 8 (IQR 6–12) before rituximab treatment and decreased to 6 (IQR 4–8) at 6 months, 6 (IQR 2–8) at 1 year and 4 (IQR 3–6) at 2 years. The C3 level improved from a baseline median of 62.5 (IQR 44.7–77.1) mg/dL to 70.8 (IQR 59.4–86.9) mg/dL at 6 months, 76.9 (IQR 61.6–90.3) mg/dL at 1 year and 80.2 (IQR 73.6–101.0) mg/dL at 2 years of rituximab use. The C4 level also improved from 9.7 (IQR 6.6–12.7) mg/dL to 16.1 (IQR 11.9–18.0) mg/dL, and the anti-dsDNA level decreased from 662 (IQR 337–1039) WHO unit/mL to 432 (IQR 182–667) WHO unit/mL within 2 years of rituximab use.

Figure 2.

Disease activity, clinical biomarkers and corticosteroid dose during the first 2 years after rituximab treatment. (A) Change in SLEDAI-2K, C3 and C4, and anti-dsDNA before and after rituximab administration in all patients. (B) Change in haemograms before and after rituximab administration in the haematological-involved group (n=12). (C) Change in renal function before and after rituximab administration in the renal-involved group (n=27). (D) Change in steroid dose before and after rituximab treatment in all patients. P<0.05 by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was considered statistically significant. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001. dsDNA, double stranded DNA; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000; WCC, white cell count.

In accordance with the EULAR/ACR classification criteria,17 haematological involvement was defined as a white cell count <4 x 109/L, platelet count <100 x 109/L or autoimmune haemolysis. Renal manifestations were defined as proteinuria >0.5 g/24 hours or lupus nephritis on renal biopsy according to the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) 2003 classification.24 In our study, 12 (30%) patients had haematological involvement and 27 (67.5%) patients had renal manifestations before rituximab treatment. As shown in figure 2B, serum platelet and haemoglobin levels significantly increased within 6 months of rituximab treatment in patients with haematological involvement. For patients with renal manifestations at baseline, the elevated daily urine protein and decreased serum albumin levels significantly improved, as shown in figure 2C. Serum creatinine levels showed a mild increase from 0.6 mg/dL to 0.8 mg/dL within 2 years, but remained within the normal range and were not clinically significant.

Rituximab treatment had a significant corticosteroid-sparing effect, as depicted in figure 2D. The equivalent oral prednisolone dose was halved after 6 months of rituximab, decreasing from 0.2 (IQR 0.2–0.8) mg/kg/day to 0.1 (IQR 0.1–0.2) mg/kg/day. A total of 14 patients (35%) attained a prednisolone equivalent dose of less than 0.1 mg/kg/day. Additionally, the cumulative corticosteroid dose decreased from 60 (IQR 37–83) mg/kg/year to 36.5 (IQR 26–60) mg/kg/year within 2 years. Notably, no increase was observed in the proportion of patients receiving pharmacological therapy for SLE before and after rituximab treatment, as illustrated in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients receiving pharmacological therapies for SLE in the RTX-treated group before and after RTX administration and the comparison group. MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; RTX, rituximab.

Disease outcomes

The outcomes of the 40 rituximab-treated patients and 53 comparison patients are outlined in table 2. In the rituximab-treated group, eight patients (20%) achieved disease control, with a mean time of 9.1 months; one of them attained clinical remission after 42 months of rituximab treatment. Five patients (12.5%) experienced flare-ups and received an increased prednisolone dose at an average time of 16.4 months. No fatalities occurred during the follow-up period. Within the comparison group, nine patients (17%) achieved disease control, within an average of 49 months after disease diagnosis. Thirty patients (56.6%) underwent steroid pulse therapy, initiated at a mean time of 19.2 months after diagnosis, with an average of 2.7 administrations. Six patients (11.3%) progressed to end-stage renal disease, requiring haemodialysis at an average of 4.4 years postdiagnosis. Four patients (7%) passed away during the follow-up period, at an average time of 5.5 years.

Table 2.

Disease outcomes and adverse effects of rituximab

| Disease outcomes | Rituximab group | Comparison group | P value |

| n (% of all patients) | n (% of all patients) | ||

| Disease control | 8 (20) | 9 (17) | 0.8 |

| Partial disease control | 27 (67.5) | 11 (20.8) | <0.01* |

| Flare-up† | 5 (12.5) | 33 (62.3) | <0.01* |

| Prednisolone increased to >0.5 mg/kg/day | 5 (12.5) | NA | NA |

| Steroid pulse therapy | 3 (7.5) | 30 (56.6) | <0.01* |

| Hospitalisation for SLE flare-up | 3 (7.5) | 33 (62.3) | <0.01* |

| SLEDAI-2K increase to >12 points | 1 (2.5) | NA | NA |

| New CYC, AZA or MTX | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Expired post-RTX | 0 (0) | 4 (7) | 0.13 |

| End-stage renal disease | 0 (0) | 6 (11.3) | 0.04* |

| Adverse effects of RTX | |||

| Allergic reactions | 2 (5) | NA | NA |

| Infection (UTI, AGE) | 2 (5) | NA | NA |

| Hypogammaglobulinaemia needing IVIG | 1 (2.5) | NA | NA |

| Viral hepatitis | 0 | NA | NA |

*p<0.05.

†Flare-up refers to events occurring after the initial rituximab dose in the rituximab-treated group and post-SLE diagnosis in the comparison group.

AGE, acute gastroenteritis; AZA, azathioprine; CYC, cyclophosphamide; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not applicable; RTX, rituximab; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Figure 4 shows the number of patients in the rituximab-treated group during follow-up and the proportion of patients under observation who achieved disease control or experienced a flare-up after rituximab administration. Nearly 20% of the patients achieved disease control within 2 years of rituximab therapy.

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients under observation who achieved disease control and partial disease control over time since rituximab therapy and those who showed flare-ups.

Adverse effects after rituximab treatment

Table 2 shows the adverse effects of rituximab treatment. Two patients (5 %) experienced mild allergic reactions, while two patients (5 %) experienced serious infections that required intravenous antibiotics. During the follow-up period, the B cell count significantly decreased from 121 (52–291)/μL to 18 (2–69)/μL (p<0.01 by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test) within 6 months. Routine measurements of IgG levels after treatment were initially performed in some patients. However, one patient (2.5 %) developed reduced IgG levels and required one course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement 7 months after rituximab administration. Before administering rituximab, none of the patients had hepatitis B or C. Throughout the follow-up period, no new cases of viral hepatitis were detected, and none of the patients exhibited an increase in liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase) exceeding three times the upper limit.

Factors associated with disease control

In this study, disease control was achieved in eight (20%) patients in the rituximab-treated group. Apart from the diagnosis-to-rituximab interval, there were no differences in demographic data, initial disease activity, number of rituximab courses, year of diagnosis or duration of follow-up between patients who achieved disease control and those who did not achieve control. The median interval between diagnosis and rituximab administration was 2.1 years (IQR 0.2–8.5) in the former group and 7.8 years (IQR 2.9–13.1 years) in the latter group.

Patients who received rituximab earlier as an SLE maintenance therapy had a higher probability of achieving disease control. Table 3 presents the results of the factors associated with disease control.

Table 3.

Comparison between patients who achieved disease control and those who did not achieve disease control

| Achieved disease control (n=8) | Did not achieve disease control (n=32) | P value | |

| Men:women | 1:7 | 5:27 | 0.9 |

| Age at disease diagnosis, median (IQR), years | 14.2 (11.3–15.2) | 14.3 (11.3–16.5) | 0.9 |

| Age at first RTX use, median (IQR), years | 17.5 (15.4–19.9) | 21.2 (17.1–28.3) | 0.06 |

| Interval of first RTX after diagnosis, median (IQR), years | 2.1 (0.2–8.5) | 7.8 (2.9–13.1) | 0.02* |

| Number of times of RTX administrations, mean (SD) | 2.9 (2) | 3.4 (2) | 0.6 |

| SLEDAI-2K before RTX, median (IQR) | 8 (5–20) | 8 (6–12) | 0.6 |

| SLEDIA-2K 2 years after RTX, median (IQR) | 2 (1–2) | 6 (4–8) | <0.01* |

| Year of diagnosis, median (IQR) | 2012 (2007–2018) | 2015 (2006–2019) | 0.8 |

| Duration of follow-up, median (IQR), years | 2.2 (1.2–4.4) | 2.9 (2.5–4.5) | 0.6 |

*p<0.05.

RTX, rituximab; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the use of rituximab as maintenance therapy for childhood-onset SLE, which was previously lacking in the literature. Unlike rescue therapy, which is administered during disease flare-ups or lupus nephritis and may require frequent dosing,7 8 12 maintenance therapy involves the use of rituximab for serologically active SLE without major clinical deterioration.14 The main objective was to administer rituximab during the early course of the disease to maintain disease activity and prevent flare-ups. As a result, many patients newly diagnosed in recent years have received rituximab early. Therefore, we enrolled newly diagnosed patients, including those with major exacerbations occurring within 3 months.

This study enrolled 40 patients with active SLE who received rituximab and another 53 patients as the comparison group. The results showed that 20% of the rituximab-treated patients achieved disease control within a mean time of 9.1 months after rituximab treatment. Additionally, the proportion of patients with renal manifestations and haematological involvement significantly improved after rituximab treatment. These findings suggest that rituximab may be a useful alternative therapy for patients with SLE who are refractory to conventional treatment or have contraindications to immunosuppressive agents.

Compared with previous studies conducted in paediatric populations,10 12 13 this study had a relatively larger sample size conducive to comprehensive analysis, an extended follow-up duration and the inclusion of a contemporary comparison group not treated with rituximab. These factors contributed to the increased internal validity of the results. This study used standardised diagnostic criteria, inclusion criteria and treatment protocols, which further increased the robustness of the findings. The dosing schedule for rituximab administration in this study was different from that in other studies, as rituximab was administered every 6 months, as opposed to every 2 weeks or every 3–4 months.7 8 12 The rationale for this dosing schedule was based on previous studies that demonstrated that rituximab has a prolonged effect on B cells and can maintain B cell depletion for up to 6 months after treatment.25 In our study, we observed that the B cell count significantly decreased within 6 months during the follow-up period, and this reduction persisted at low levels for an extended period. Moreover, longer dosing intervals may reduce the risk of adverse effects associated with frequent rituximab administration, such as infusion reactions, infections and hypogammaglobulinaemia.26–29 None of the patients had hepatitis B or C infection before or throughout the follow-up period.

Maintenance therapy offers several advantages over rescue therapy, one of which is its ability to prevent disease flares and reduce the need for rescue therapies such as steroid pulse therapy.30 31 In addition, the current investigation provides evidence of the corticosteroid-sparing effect of rituximab, as indicated by a decrease in the dosage of equivalent oral prednisolone and cumulative corticosteroid utilisation, which aligns with the results of previous research.11 The proportion of patients who received pharmacological interventions for SLE did not increase after rituximab treatment.

Regarding the outcomes of our study, disease control was achieved in 20% of the rituximab-treated patients with a mean duration of 9.1 months. In contrast, the comparison group showed a similar proportion achieving disease control but required a more extended period. Furthermore, 12.5% of the rituximab-treated patients experienced a flare-up during the follow-up period and no fatalities were reported. In contrast, the comparison group exhibited a higher incidence of disease flare-ups, necessitating more frequent steroid pulse therapy. Additionally, a greater number of patients in the comparison group progressed to end-stage renal disease and had a higher mortality rate, compared with a previous study conducted at the NTUH which enrolled 72 children diagnosed with SLE between 1980 and 2001.32 In that study, the 5-year renal survival rate (survival without dialysis or transplantation) was 63.13% and the 10-year survival rate was 53.54%. The rituximab-treated group in our study demonstrated superior outcomes in comparison; however, it is important to consider potential selection bias.

Regarding the factors associated with disease outcomes, our study demonstrated that the diagnosis-to-rituximab interval was the sole significant factor, suggesting that patients who received rituximab earlier as an SLE maintenance therapy were more likely to achieve disease control. Longer follow-up durations and advancements in treatment may potentially affect disease outcomes, as the year of diagnosis could influence efficacy. However, our analysis found no significant differences between the years of diagnosis and the duration of follow-up. Previous studies have analysed factors predicting disease outcomes in patients with SLE treated with rituximab. Among these factors, B cell depletion and repopulation have been identified as predictors of clinical outcomes.33 Other factors reported to influence rituximab efficacy in SLE include the Fc gamma RIIIa genotype, higher baseline CD19+ B cell counts, early B cell depletion failure, African race and an expanded autoantibody profile at baseline.5 34–36

The strength of the study is that we have provided beneficial evidence of adding rituximab to maintenance therapy for relatively stable patients with paediatric-onset SLE. Furthermore, the inclusion of a contemporary comparison group receiving DMARD as the mainstay treatment enhances the depth of our data analysis. Some study limitations must be considered. First, this was a retrospective analysis of data from a single centre, which limited the generalisability of the findings. Second, the study did not collect data on patient-reported outcomes such as quality of life, which could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of rituximab treatment. Finally, we did not evaluate the long-term safety of rituximab treatment in patients with SLE, which is an important consideration for its use in clinical practice.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that rituximab is effective and safe as an add-on maintenance therapy among patients with paediatric-onset SLE who are serologically active without major clinical deterioration. Notably, rituximab showcases superior disease outcomes, characterised by a quicker attainment of disease control, reduced flare-ups and lower incidence of end-stage renal disease and mortality. An early administration of rituximab as SLE maintenance therapy resulted in a higher probability of achieving disease control. However, further case–control studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are necessary to confirm the efficacy and safety of rituximab as maintenance therapy for SLE.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Dr. Uei-Hsiang Hsu, Dr. Chin-Yin Ho and Dr. Wei-Chen Kao for their assistance in collecting data for the comparison group.

Footnotes

Contributors: Concept and design: T-WL, Y-TL, Y-CH, H-HY, B-LC. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: T-WL, B-LC. Drafting of the manuscript: T-WL. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Guarantor: T-WL, B-LC.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the National Taiwan University Hospital Research Ethics Committee (NTUH-REC no: 201812007RIND). Due to the retrospective nature of this study, obtaining informed consent from the participants is not applicable.

References

- 1.Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2008;358:929–39. 10.1056/NEJMra071297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamphuis S, Silverman ED. Prevalence and burden of pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010;6:538–46. 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sousa S, Gonçalves MJ, Inês LS, et al. Clinical features and long-term outcomes of systemic lupus erythematosus: comparative data of childhood, adult and late-onset disease in a national register. Rheumatol Int 2016;36:955–60. 10.1007/s00296-016-3450-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pescovitz MD. Rituximab, an anti-Cd20 Monoclonal antibody: history and mechanism of action. Am J Transplant 2006;6:859–66. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01288.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mok CC. Current role of Rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Rheum Dis 2015;18:154–63. 10.1111/1756-185X.12463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos-Casals M, Soto MJ, Cuadrado MJ, et al. Rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review of off-label use in 188 cases. Lupus 2009;18:767–76. 10.1177/0961203309106174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weidenbusch M, Römmele C, Schröttle A, et al. Beyond the LUNAR trial. efficacy of Rituximab in refractory lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:106–11. 10.1093/ndt/gfs285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condon MB, Ashby D, Pepper RJ, et al. Prospective observational single-centre cohort study to evaluate the effectiveness of treating lupus nephritis with Rituximab and mycophenolate mofetil but no oral steroids. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1280–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong Z, Li H, Zhong H, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of Rituximab in lupus nephritis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2019;13:845–56. 10.2147/DDDT.S195113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basu B, Roy B, Babu BG. Efficacy and safety of Rituximab in comparison with common induction therapies in pediatric active lupus nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol 2017;32:1013–21. 10.1007/s00467-017-3583-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson L, Beresford MW, Maynes C, et al. The indications, efficacy and adverse events of Rituximab in a large cohort of patients with juvenile-onset SLE. Lupus 2015;24:10–7. 10.1177/0961203314547793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahmoud I, Jellouli M, Boukhris I, et al. Efficacy and safety of Rituximab in the management of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review. J Pediatr 2017;187:213–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawhney S, Agarwal M. Rituximab use in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: indications, efficacy and safety in an Indian cohort. Lupus 2021;30:1829–36. 10.1177/09612033211034567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassia MA, Alberici F, Jones RB, et al. Rituximab as maintenance treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus: A multicenter observational study of 147 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1670–80. 10.1002/art.40932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petri M, Orbai A-M, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the systemic lupus International collaborating clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2677–86. 10.1002/art.34473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochberg MC. Updating the American college of rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1725. 10.1002/art.1780400928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. European League against rheumatism/American college of rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1400–12. 10.1002/art.40930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gladman DD, Ibañez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol 2002;29:288–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tselios K, Gladman DD, Touma Z, et al. Clinical remission and low disease activity outcomes over 10 years in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:822–8. 10.1002/acr.23720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teng YKO, Bruce IN, Diamond B, et al. Phase III, Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 104-week study of subcutaneous Belimumab administered in combination with Rituximab in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): BLISS-BELIEVE study protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025687. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikdashi J, Nived O. Measuring disease activity in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus: the challenges of administrative burden and responsiveness to patient concerns in clinical research. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:183. 10.1186/s13075-015-0702-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narayanan K, Marwaha V, Shanmuganandan K, et al. Correlation between systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index, C3, C4 and anti-dsDNA antibodies. Med J Armed Forces India 2010;66:102–7. 10.1016/S0377-1237(10)80118-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis P, Cumming RH, Verrier-Jones J. Relationship between anti-DNA antibodies complement consumption and circulating immune complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Immunol 1977;28:226–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus Revisited. Kidney Int 2004;65:521–30. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00443.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leandro MJ, Cooper N, Cambridge G, et al. Bone marrow B-lineage cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis following Rituximab therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:29–36. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fouda GE, Bavbek S. Rituximab hypersensitivity: from clinical presentation to management. Front Pharmacol 2020;11:572863. 10.3389/fphar.2020.572863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsutsumi Y, Kanamori H, Mori A, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus with Rituximab. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2005;4:599–608. 10.1517/14740338.4.3.599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tieu J, Smith RM, Gopaluni S, et al. Rituximab associated Hypogammaglobulinemia in autoimmune disease. Front Immunol 2021;12:671503. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.671503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khojah AM, Miller ML, Klein-Gitelman MS, et al. Rituximab-associated Hypogammaglobulinemia in pediatric patients with autoimmune diseases. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2019;17:61. 10.1186/s12969-019-0365-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groot N, de Graeff N, Marks SD, et al. European evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of childhood-onset lupus nephritis: the SHARE initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1965–73. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mina R, von Scheven E, Ardoin SP, et al. Consensus treatment plans for induction therapy of newly diagnosed proliferative lupus nephritis in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:375–83. 10.1002/acr.21558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang LC, Yang YH, Lu MY, et al. Retrospective analysis of the renal outcome of pediatric lupus nephritis. Clin Rheumatol 2004;23:318–23. 10.1007/s10067-004-0919-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vital EM, Dass S, Buch MH, et al. B cell biomarkers of Rituximab responses in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3038–47. 10.1002/art.30466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anolik JH, Campbell D, Felgar RE, et al. The relationship of Fcgammariiia genotype to degree of B cell depletion by Rituximab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:455–9. 10.1002/art.10764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cambridge G, Isenberg DA, Edwards JCW, et al. B cell depletion therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus: relationships among serum B lymphocyte Stimulator levels, autoantibody profile and clinical response. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1011–6. 10.1136/ard.2007.079418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albert D, Dunham J, Khan S, et al. Variability in the biological response to anti-Cd20 B cell depletion in systemic lupus Erythaematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1724–31. 10.1136/ard.2007.083162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.