Abstract

Objectives

Communication is a main challenge in migrant health and essential for patient safety. The aim of this study was to describe the satisfaction of caregivers with limited language proficiency (LLP) with care related to the use of interpreters and to explore underlying and interacting factors influencing satisfaction and self-advocacy.

Design

A mixed-methods study.

Setting

Paediatric emergency department (PED) at a tertiary care hospital in Bern, Switzerland.

Participants and methods

Caregivers visiting the PED were systematically screened for their language proficiency. Semistructured interviews were conducted with all LLP-caregivers agreeing to participate and their administrative data were extracted.

Results

The study included 181 caregivers, 14 of whom received professional language interpretation. Caregivers who were assisted by professional interpretation services were more satisfied than those without (5.5 (SD)±1.4 vs 4.8 (SD)±1.6). Satisfaction was influenced by five main factors (relationship with health workers, patient management, alignment of health concepts, personal expectations, health outcome of the patient) which were modulated by communication. Of all LLP-caregivers without professional interpretation, 44.9% were satisfied with communication due to low expectations regarding the quality of communication, unawareness of the availability of professional interpretation and overestimation of own language skills, resulting in low self-advocacy.

Conclusion

The use of professional interpreters had a positive impact on the overall satisfaction of LLP-caregivers with emergency care. LLP-caregivers were not well—positioned to advocate for language interpretation. Healthcare providers must be aware of their responsibility to guarantee good-quality communication to ensure equitable quality of care and patient safety.

Keywords: ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, Health Equity, PAEDIATRICS, communication

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The mixed methods approach allowed to measure the satisfaction with care of caregivers with limited language proficiency and also to explore underlying reasons.

Root causes for unfrequent caregiver self-advocacy for professional language interpretation were detected.

By systematically assessing and comparing comprehension of diagnosis and treatment to the self-reported comprehension of caregivers, important discrepancies were detected.

Participation of professional interpreters and study participants in designing and analysing the data increased the validity of the study and accuracy of the findings.

The study group where an interpreter was used was small, not allowing for further, inferential statistical testing.

Introduction

Language barriers and insufficient communication are major challenges in migrant healthcare delivery, leading to decreased access and quality of care.1–7 In Switzerland, an estimated 10% of the population face language barriers on a daily base as they either do not speak one of the four national languages or have another preferred language.8 9 This proportion was further increased by the recent influx of Ukrainian refugees.10 Under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Switzerland declares to provide every child with access to the highest attainable standard of healthcare.11 Successful communication, preferably with professional interpreters, is widely described as essential to minimise disparities in the quality of healthcare for these patients.1 4 8 12–15 A Swiss legal report underscored that the right to receive language interpretation is part of any informed consent process in patients speaking other languages than the health providers.16 Yet, international evidence clearly shows that professional interpreters are underused in healthcare settings.1 17–26

A literature review including studies from the USA, Australia, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Canada investigated the impact of language proficiency on the patient’s experience in healthcare and found that impaired communication, relationship, discrimination and cultural safety were main concerns. Factors improving the healthcare experience of patients with limited language proficiency (LLP) were mitigating language barriers through interpreters, offering translated patient resources improve transcultural competencies of healthcare professionals and enhance education for community resources for LLP caregivers.27 28 Other studies recommended systematic communication pathways for LLP patients,10 including improved guidelines on the use of interpreters, minimised barriers to access interpreter services, including sufficient financial coverage, and raised awareness about the importance of the use of interpreters among health workers.1 17–19 21 29 30 Improvements of the healthcare delivery to LLP patients were most successful if a participatory approach was chosen.31 Despite the considerable proportion of the population in Switzerland with LLP, evidence focusing on their perspective on the quality of healthcare related to communication is missing.

The goal of this study was to describe the satisfaction of LLP-caregivers related to the use of interpreters as a driver of quality of paediatric emergency care and to explore underlying, interacting factors influencing satisfaction.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted at the paediatric emergency department (PED) of the University Hospital of Bern, Switzerland. The department provides the full range of emergency care for children and adolescents aged 0–16 years to an average of over 30 000 patients per year. Since 2021, it is part of the ‘Swiss health network for equity’.32 An around-the-clock phone interpreter service is provided at the facility, and it is offered to patients free of charge, with the department covering the costs. For planned conversations (mostly on the wards or in outpatient clinics), in-person interpreters can be ordered on demand. The costs are covered by the hospital.

Study design

This study is a concurrent design mixed-method study (online supplemental figure 1). As this study aimed to explore caregivers’ satisfaction related to the use of interpreters as part of healthcare management and delivery, it explored satisfaction in the context of a broad, complex and multidimensional field. In such cases, a mixed-methods research design is known to offer multiple advantages,33 including the examination of the research question from multiple perspectives,34 the triangulation of two different methods and several forms of data35–38 and the pragmatic flexibility of the methodology to adapt to the specific research question and context.39 40 The most recent Equator network recommended standardised mixed-method research guidelines were used for the reporting of the study (online supplemental table 1).41

bmjopen-2023-077716supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

The primary objective was to compare the LLP-caregivers’ satisfaction with healthcare with and without the use of professional interpreters. Secondary objectives were the analysis of self-reported versus assessed language proficiency, the comprehension of diagnosis and received therapy of their child, and their communication strategy and desire for professional interpreters.

This study was nested into an interventional study intended to increase the use of professional interpreter services.26 Consequently, data collection for this study was done during the predefined two time periods.

Patient and public Involvement

The research question of this study was developed after multiple informal discussions with caregivers of patients presenting at the department who experienced language barriers. A professional interpreter with migrant background and one migrant caregiver were included during the creation and revision of the interview guideline and during the analysis of the results. The results of the study will be shared with the team of professional interpreters providing language interpretation at the emergency department and with the migrant caregivers involved in this study who wished to receive the finalised publication.

Study population

All patients visiting the emergency department between 1 April 2021 and 30 June 2021 (first recruitment period) and between 1 October and 5 December 2021 (second recruitment period) were screened for the following inclusion criteria using the administrative records: (1) nationality other than Swiss AND (2) Swiss nationality with national language other than German (G), French (F) or English (E) AND iii) not presenting only for a COVID-19 swab test.

All caregivers of patients who visited the emergency department and fulfilled the inclusion criteria were systematically called and screened for their language proficiency within 1 week after their consultation. If two caregivers were present at the consultation, the one with better language skills was screened. The ABC-tool,42 a globally used standardised, multidimensional language proficiency screening tool, was adapted by the study team to the local context. Every caregiver who visited the PED and met the inclusion criteria was screened and their language proficiency classified, using the scoring system defined by the ‘Goethe Institute’, the most established international language school for German.43 The scoring ranges from A1 (very LLP) to C1 (fluent). All caregivers screened as A1 or A2 were classified as caregivers with LLP. If the screening was positive and caregivers agreed to receive a phone call, the LLP caregiver was contacted a few days later for a semistructured phone interview with a professional interpreter. Prior to each interview, verbal informed consent was obtained from the LLP caregiver with the assistance of professional interpreters. The caregivers who completed the study interview represented the final study population.

Data collection

Following recommendations of Creswell and Zhang,44 quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously. The quantitative data included electronic health records and quantitative measurements of the caregivers’ satisfaction. The qualitative data consisted of semistructured interviews. Both data sets were analysed in parallel and relationships between the condensed qualitative and quantitative results were visualised to obtain an in-depth understanding of caregivers’ satisfaction and its underlying factors. Quantitative and qualitative data collection, including phone call screenings and interviews, was conducted by author 1 and 3. During the study period, they were employed as doctoral candidates at the PED of the University’s Hospital in Bern in the migrant health service research group. Both researchers had previous experience in paediatric migrant health research and were trained by author 2 and 8 in the conduction of diversity-sensitive, semistructured interviews using presentations, role-play and educational videos. Author 8 has extensive experience in qualitative research and paediatric migrant health.

Qualitative data

Two semistructured interview guides were designed by the interprofessional study team using different versions for consultations with and without the use of professional interpreters (online supplemental table 2). The questionnaire entailed closed (quantitative data) and open (qualitative data) questions.

The interview guides were discussed with and reviewed by a professional and experienced interpreter with migrant background. After external revision, pilot interviews were performed to assess comprehensibility, acceptability and interview-duration as to ensure that the information needed to answer the research questions was being produced. The preliminary interviews were discussed within the research team and analysed in joint team sessions. The final interview guideline included mandatory core questions exploring reasons for the perceived quality of care with a focus on communication and the caregiver’s confidence while communicating. Core questions were followed by non-mandatory prompts, allowing the interviewer to further explore interesting comments made by the caregiver.

All interviews were conducted with a professional phone interpreter who translated the caregiver’s preferred language to German using iPhone SE/6’s conference mode (V.iOS 15.1/12.5.5).

Quotes from interviews of caregivers during health encounters using a professional interpreter were cited with A. Those without interpreter services were cited with B, followed by the interview number.

Quantitative data

For each participant, the following quantitative variables were extracted from routine administrative health records: nationality, age, gender, date of visit, diagnosis, therapy and triage score. An Emergency Triage Scale (STS), ranging from 1: acute life-threatening to 5: non-urgent, was used.45 Further variables were collected during the phone interview: satisfaction, accompanying person/s, native language, self-reported and estimated language skills in G/E/F, interpreter use, the child’s diagnosis, therapy received, recency of immigration to Switzerland, caregiver’s education and resident status.

Caregivers were asked about their satisfaction with the health encounter ranging from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 6 (very satisfied). To describe the self-reported language comprehension, caregivers were asked if the information they received during the emergency department visit was understandable. The answers were classified as yes, partially, or no. To assess comprehension, the study team asked caregivers to explain the diagnosis and the treatments the child received during the health visit. If the caregivers’ answers corresponded to the diagnosis and treatments recorded in the electronic medical report, they were marked as match. Partial matches or discrepant answers were documented as partially correct or incorrect.

Data management and analysis

All data were entered into a REDCap-database (Vanderbilt University/IC 6.9.4, 2018).

For quantitative data, entry fields were designed as binary radio button fields or scroll down lists. Branching logic was used where appropriate.

REDCap data quality control tests were performed before analysis. STATA (Stata/IC V.13.1. 2013) was used for statistical analysis.

Qualitative data were transcribed simultaneously to the phone interview and directly entered in the REDCap database. Three free-text fields summarised statements about the general patient satisfaction, two text fields documented caregivers’ descriptions of his/her comprehension during the health visit, and one additional text field was used for further interesting statements. For each of the three groups of free-text fields, answers from all participants were pooled together in one document and coded deductively and inductively by two coders (authors 1 and 2) using the text analysis approach according to Mayring.46 Citations from LLP-caregivers in the interpreter group were compared with those from the non-interpreter group. Saturation was monitored continuously throughout recruitment and data collection and continued until new data mainly repeated information collected in previous interviews.47 Saturation of the material was reached in both groups.

During multiple online and in-person meetings, data were analysed in a stepwise approach in an interprofessional team. The team included the authors of this study, a professional interpreter with migrant background and one migrant caregiver. Through stepwise aggregation of the qualitative data, the resulting main categories were created. The relationships between the condensed qualitative and quantitative results was visualised in multiple networks, illustrating the final outcomes of this study.

Results

Study population

A total of 181 caregivers were included in this study. Of those, 14 (7.7%) had a consultation with, and 167 (92.3%) had a consultation without an interpreter (online supplemental figure 2). In consultations, using an interpreter, the most frequent nationalities were Eritrean 6/14 (42.9%), Syrian 3/14 (21.4%) and Sri Lankan 2/14 (14.3%). A total of 57.1% (8/14) received an urgent triage score. Most caregivers graduated from primary school 6/14 (42.9%) followed by secondary school 5/14 (35.7%), while 2/14 (14.3%) were illiterate.

The most common nationalities in consultations without an interpreter were Syrian 37/167 (22.2%), Eritrean 26/167 (15.6%) and Portuguese 13/167 (7.8%). A total of 25.1% (42/167) received an urgent triage score. The most frequent educational degree of these caregivers was secondary school 64/167 (38.3%), followed by primary school 56/167 (33.5%). 12.6% (21/167) were illiterate (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| With interpreter (14) | Without interpreter (167) | |||||||

| N/years | % | N/years | % | |||||

| Most frequent nationalities | ER | 6 | 42.9 | SY | 37 | 22.2 | ||

| SY | 3 | 21.4 | ER | 26 | 15.6 | |||

| LK | 2 | 14.3 | PT | 13 | 7.8 | |||

| AF | 1 | 7.1 | AF | 11 | 6.6 | |||

| IQ | 1 | 7.1 | TR | 10 | 6 | |||

| SO | 1 | 7.1 | LK | 9 | 5.4 | |||

| Most frequent languages | Tigrinya | 6 | 42.9 | Arabic | 38 | 22.6 | ||

| Arabic | 3 | 21.4 | Tigrinya | 25 | 15 | |||

| Tamil | 2 | 14.3 | Kurdish | 16 | 9.5 | |||

| Dari | 1 | 7.1 | Portuguese | 14 | 8.4 | |||

| Kurmanji | 1 | 7.1 | Turkish | 13 | 7.8 | |||

| Somali | 1 | 7.1 | Albanish | 12 | 7.2 | |||

| Language proficiency | Estimated | Self-reported | Estimated | Self-reported | Estimated | Self-reported | Estimated | Self-reported |

| A1 | 7 | 5 | 50 | 35.7 | 66 | 30 | 39.5 | 18 |

| A2 | 7 | 4 | 50 | 28.6 | 100 | 35 | 59.9 | 21 |

| B1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 35.7 | 1 | 45 | 0.6 | 26.9 |

| B2 | 39 | 23.4 | ||||||

| C1 | 12 | 7.2 | ||||||

| C | 4 | 2.4 | ||||||

| Missing | 2 | 1.2 | ||||||

| Duration of stay in CH | 5.07 years | 6.71 years | ||||||

| (min – max) | (20d–12y) | (6d–30y) | ||||||

| Triage score | ||||||||

| 1–3: urgent | 8 | 57.1 | 42 | 25.1 | ||||

| 4–5: non-urgent | 6 | 42.9 | 124 | 74.3 | ||||

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 0.6 | |||||

| Highest education degree of caregiver | ||||||||

| Illiterate | 2 | 14.3 | 21 | 12.6 | ||||

| Primary school | 6 | 42.9 | 56 | 33.5 | ||||

| Secondary school | 5 | 35.7 | 64 | 38.3 | ||||

| University | 0 | 0 | 26 | 15.6 | ||||

| Asylum permission/residence status | ||||||||

| N-permit | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.8 | ||||

| F-permit | 5 | 35.7 | 33 | 19.8 | ||||

| B-permit | 6 | 42.9 | 93 | 55.7 | ||||

| C-permit | 1 | 7.1 | 25 | 15 | ||||

| Not known | 1 | 7.1 | 9 | 5.4 | ||||

B-permit, temporary resident foreign nationals; C-permit, settlement permit; d, day; F-permit, temporarily admitted refugee; N-permit, asylum-seeker; y, year.

Overall satisfaction

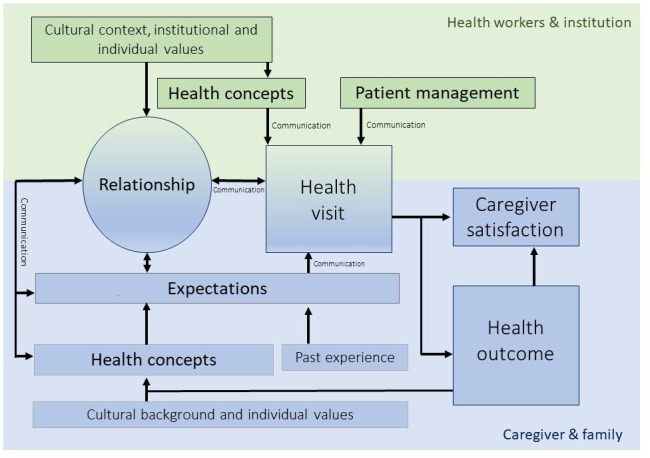

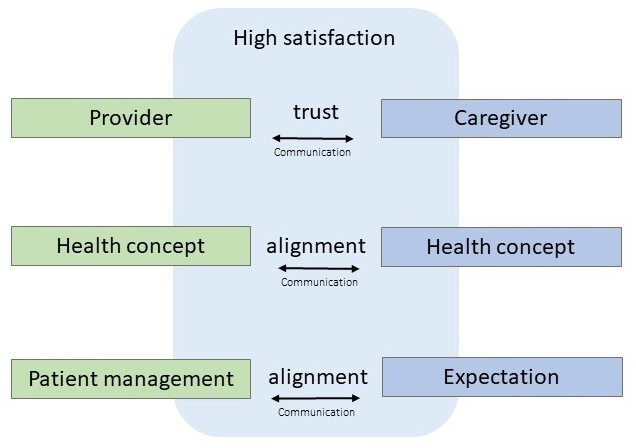

The satisfaction was high in both groups with a total mean of 4.9 (SD ±1.6). Caregivers in consultations with an interpreter were more satisfied than those in the non-interpreter group (5.5 (SD) ±1.4 vs 4.8 (SD) ±1.6; table 2). Satisfaction was influenced by five main factors: relationship with the health workers, patient management, alignment of health concepts, caregivers’ personal expectation and health outcome of the patient (figure 1). Satisfaction was optimal when the patient management met the caregiver’s expectation, the relationship between health workers and caregivers was respectful and trustful, and when there was agreement on the same health concept (figure 2). Communication was the main tool able to modulate relationships, expectations and health concepts influencing satisfaction through these factors.

Table 2.

Quantitative data

| With interpreter (14) | Without interpreter (167) | |||||

| N/mean | %/SD | N/mean | %/SD | |||

| General satisfaction* | Mean/SD | 5.46 | 1.39 | 4.8 | 1.59 | |

| 1 | 1 | 7.1 | 11 | 6.6 | ||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 6.6 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 7.2 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 9.6 | ||

| 5 | 2 | 14.3 | 31 | 18.6 | ||

| 6 | 10 | 71.4 | 84 | 50.3 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 7.1 | 2 | 1.2 | ||

| Communication | ||||||

| Language barrier | Yes | NA | NA | 88 | 52.7 | |

| A1 | NA | NA | 43 | 48.9 | ||

| A2 | 45 | 51.1 | ||||

| No | NA | NA | 75 | 44.9 | ||

| A1 | NA | NA | 18 | 24 | ||

| A2 | 54 | 72 | ||||

| B1 | 1 | 1.3 | ||||

| Missing | NA | NA | 4 | 2.4 | ||

| Non-professional interpreter | Yes | NA | NA | 58 | 34.7 | |

| Siblings | NA | NA | 8 | 13.8 | ||

| Family member | 10 | 17.2 | ||||

| Friend | 17 | 29.3 | ||||

| Hospital staff | 5 | 8.6 | ||||

| Patient | 17 | 29.3 | ||||

| Other | 1 | 1.7 | ||||

| Of which minors | NA | NA | 25 | 43.1 | ||

| No | NA | NA | 105 | 62.9 | ||

| Missing | NA | NA | 4 | 2.4 | ||

| Self-reported and assessed comprehension | ||||||

| Understandable information | Self-reported comprehension=good | 12 | 85.7 | 114 | 68.3 | |

| Correct diagnosis | Yes | 4 | 33.3 | 49 | 43 | |

| Partial | 8 | 66.7 | 45 | 39.5 | ||

| Insufficient | 0 | 0 | 18 | 15.8 | ||

| Missing | 2 | 1.8 | ||||

| Correct therapy | Yes | 5 | 41.7 | 47 | 41.2 | |

| Partial | 6 | 50 | 55 | 48.3 | ||

| Insufficient | 1 | 8.3 | 8 | 7 | ||

| Missing | 4 | 3.5 | ||||

| Self-reported comprehension=partial | 2 | 14.3 | 36 | 21.6 | ||

| Correct diagnosis | Yes | 2 | 100 | 15 | 41.7 | |

| Partial | 0 | 0 | 17 | 47.2 | ||

| No | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8.3 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2.8 | ||||

| Correct therapy | Yes | 0 | 0 | 16 | 44.4 | |

| Partial | 2 | 100 | 15 | 41.7 | ||

| Insufficient | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11.1 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2.8 | ||||

| Self-reported comprehension=insufficient | 0 | 0 | 11 | 6.6 | ||

| Correct diagnosis | Yes | 0 | 0 | 4 | 36.4 | |

| Partial | 0 | 0 | 6 | 54.5 | ||

| Insufficient | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9.1 | ||

| Correct therapy | Yes | 0 | 0 | 4 | 36.4 | |

| Partial | 0 | 0 | 7 | 63.6 | ||

| Insufficient | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3.6 | ||

| Interpreter use | ||||||

| Interpreter—sensible and helpful? | Yes | 14 | 100 | NA | NA | |

| Interpreter desired | Yes | NA | NA | 89 | 53.3 | |

| No | NA | NA | 74 | 44.3 | ||

| Missing | NA | NA | 4 | 2.4 | ||

| Knowledge about interpreter entitlement | Yes | 7 | 50 | 37 | 22.2 | |

| No | 6 | 42.9 | 125 | 74.9 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 7.1 | 5 | 3 | ||

*General satisfaction: 1=not satisfied, 6=very satisfied.

NA, not applicable.

Figure 1.

Framework of factors influencing satisfaction.

Figure 2.

Framework prerequisite for a high satisfaction.

Satisfaction related to the use of interpreters

In both groups, caregivers mentioned good communication as a key precondition for their satisfaction with the health encounter. In the group with an interpreter, all caregivers described the organisation of interpreters as a sensible and helpful part of the patient management. The opinion on how often and when an interpreter was needed varied. Two caregivers thought an interpreter was only necessary for complex conversations.

At the beginning I could communicate well, but when it became more complicated, the hospital organized an interpreter. That was great! (A 8; Satisfaction score 6)

In the group without interpreter services, important language barriers were mentioned by 53.7% (88/167) of the caregivers. Around 21% (35/167) explicitly described miscommunication and frustration during their visit. Some also thought of the health workers’ perspective and acknowledged that the situation was frustrating for them as well.

Despite not having language interpretation, 44.9% (75/167) were satisfied with the communication. Of all caregivers in the group without language interpretation, 100 (59.9%) had a higher self-reported language proficiency score than the score they received during the standardised language screening done by the researchers. Of those, 59% did not think a professional interpreter was necessary.

A total of 58/167 (34.7%) caregivers reported that they communicated through a non-professional interpreter. Of these, 43.1% (25/58) were minors with a mean age of 12.4 (11–14 IQR). The youngest non-professional interpreter was 7 years old.

Some caregivers preferred professional interpreters for reasons of confidentiality, whereas some favoured non-professional interpreters with the argument that they knew and trusted them or that they were more rapidly available than professional interpreters. One caregiver explained that they decided not to ask for language interpretation because they were worried about prolonged waiting times. As consequence, s/he guessed the answer to questions:

I would have liked an interpreter, but I was afraid that the organization would take too long. Therefore, I did not say that I did not understand certain things and simply said ‘yes’. If I had known that there were also phone interpreters, I would have been very happy to use one. (B 17; Satisfaction score 4)

A minority of 22.2% (37/167) of caregivers knew they were entitled to receive free of charge language interpretation during health consultations. A total of 61/167 (36.5%) caregivers explicitly said they would have asked for an interpreter had they known about that option.

As for the overall communication, satisfaction with comprehension differed between the two study groups. Caregivers with interpreters were more likely to describe comprehension as good (85.7% (12/14) vs 68.3% (114/167)). In contrast to caregivers without interpreter services, they never classified communication as insufficient. With one exception, all parents recalled the diagnosis and therapy of their children at least partially correctly, whereas some caregivers in the group without interpreters could not recall diagnosis (13.2% 22/167) or therapy (7.2% 12/167). In both groups, strong discrepancies existed between self-reported and assessed language comprehension (table 2).

Expectation

A key factor for satisfaction was the caregivers’ personal expectations, which were shaped by cultural background, health concepts and previous experiences with healthcare systems (figure 1). Many caregivers were used to experiencing communication barriers in daily life. Using their children as interpreters was often considered normal routine. One mother reported that her 8-year-old child translated for her and admitted:

I did not understand what exactly was done during the operation. (B 90; Satisfaction score 6)

Nevertheless, she did not criticise that no interpreter was consulted for her and was highly satisfied. About 4.2% (7/167) of caregivers reported that they requested during this or a previous health visit language interpretation at the emergency department, but their request was rejected.

I asked for an interpreter, but I was told it was too expensive and I couldn’t get one. Then I called a friend, she translated for me. But it was about very intimate things and then everyone noticed. You can’t do that! (B 99; Satisfaction score 3)

Expectations also influenced satisfaction with patient management. Depending on expectations, caregivers experienced wait times as long or short (long: 44.8% (81/181) short: 15.5% (28/181)) without correlation to the objective wait time. The degree to which the wait time affected satisfaction also varied strongly. Some caregivers who expected to receive medical treatment very quickly had lower satisfaction scores. Others appreciated the 24 hours service and attended the emergency department after their working hours or on weekends, preferring to wait in the emergency department to waiting for an appointment with their paediatrician.

Unmet expectations negatively influenced the relationship with the health workers. If mismatches in health workers’ actions and caregivers’ expectations remained unresolved, satisfaction decreased. Misunderstandings and miscommunication contributed to dissatisfaction as they impeded the ability of the staff to identify and respond to the caregivers’ expectations. If gaps between health workers’ actions and caregivers’ expectations could not be identified and bridged, it resulted in dissatisfaction.

I am very dissatisfied. The doctor was not a real doctor. She only talked for 1 hour and did not do a good examination nor a lab. (B 10; Satisfaction score 1)

Health concepts

Another key factor influencing satisfaction was the alignment of health workers’ and caregivers’ health concepts. The cultural background of the caregivers influenced the health concept and therefore the concept of the child’s disease and the expectation what the child needed. Satisfaction decreased if there was an unresolved mismatch between the caregivers’ and the health workers’ health concepts. Most caregivers expected more diagnostics (blood work) and therapies (antibiotics, intravenous fluids). In two cases (assessed and reported comprehension: good in both cases), the caregivers’ health concept was transformed during and after the health encounter. As the outcome for the child was favourable by the time of the interview, caregivers understood that the initially expected blood work in the emergency department had not been necessary. Good communication and comprehension, a trustful relationship, and a positive health outcome mediated the transformation of the caregivers’ health concept, leading to alignment with the health workers’ practice. The only case in the interpreter group with very low satisfaction was due to a mismatch of health concepts that could not be resolved despite good communication assured by an interpreter.

I was not satisfied with the consultation. The situation of my child was very serious, so I wished for an infusion. The nursing staff did not agree and did not do anything. (A 14; Satisfaction score 1)

Relationship

A trustful and respectful health worker–caregiver relationship also represented a key factor for satisfaction (figures 1 and 2). For some caregivers, friendly and respectful treatment gave the impression that the child’s medical team was competent.

The respect! I felt taken seriously and treated well. (A 2; Satisfaction score 6)

All statements describing the relationship with the staff were positive in the interpreter group. Once established, trustful relationships also helped to keep satisfaction high despite existing language barriers; like in the following example where the caregiver was satisfied with the whole health visit:

The nursing staff and doctors are very nice and competent, they treated us with love. (A 4; Satisfaction score 6)

Patient management

A fourth key factor influencing the caregiver’s satisfaction was the patient management. This included waiting times, the triage system, organisation of language interpretation, COVID-19 restrictions, and quality improvement.

Many caregivers were not familiar with the triage system of prioritising sicker patients. Seeing children get treated earlier although they arrived later triggered the feeling of inequity and injustice.

Not all patients were treated the same. I don’t know if it has to do with the language. Other children got treated before us and we had to wait for so long. I felt discriminated. (B 117; Satisfaction score 2)

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, only one person was allowed to stay with the child during the health visit. This was mentioned as a problem, as sometimes one caregiver knew more about the child’s health condition, but the other was more language-proficient. As one had to leave, the ability to communicate was impaired:

The father translated the medical history on the phone because he speaks German well. After that, there were communication difficulties because I don’t speak German very well. I did not understand a lot of what the doctor said. (B 87; Satisfaction Score 4)

Most of the caregivers were very satisfied with the patient management. They also appreciated being contacted for the interview for quality improvement and receiving information about interpreters being available anytime and free of charge.

All people who can’t speak German well have difficulties with communication at the hospital and would like to have an interpreter. Thank you for your work and effort. (B 74; Satisfaction score 4)

Discussion

This study exploring the perception of the quality of paediatric emergency care among LLP-caregivers showed increased satisfaction of caregivers when professional language interpretation was used. The most frequently mentioned factors contributing to satisfaction, modulated by interpreter use, were satisfied personal expectations, aligned health concepts, a respectful and trustful caregiver–health worker relationship and good patient management. Caregivers were generally satisfied with their emergency department experience, but many had low expectations regarding communication quality. Overestimation of personal language skills was common and caregivers were often unaware of the option to get professional language interpretation.

The large difference in the size of the two study groups may be due to the fact that the telephone screening does not fully reflect the situation in the emergency department. However, the results are in line with current evidence, demonstrating that a very high number of caregivers with LLP does not receive language interpretation during health visits, resulting in inferior quality of care.1 17 19

In our study, caregivers’ satisfaction with healthcare was higher when professional interpreters were involved and understanding of diagnosis and treatment improved. This is well in line with strong evidence, including three literature reviews, describing higher patient satisfaction, fewer interpretation mistakes and increased quality of care when using professional interpreters during health visits for LLP patients.4 48 49 While all the caregivers in the interpreter group described positive effects of professional language interpretation, a total of 44.9% of LLP-caregivers in the non-interpreter group were also satisfied with the communication. Findings showed a common overestimation of the personal language proficiency, low expectations regarding communication quality and unawareness of the option to get professional language interpretation as explanations. This is in line with other studies describing that LLP-patients overestimated their language skills,50 rarely advocated for language interpretation and were unaware of their own right to good-quality communication.30 The finding of low caregivers’ expectation related to communication is a concerning safety risk. If good communication is not ensured, caregivers are not allowed to play their role as important advocates for their child’s health and safety. Being used to inferior standards to the extent that a person accepts the inferior treatment as normal is described in the literature as part of internalised discrimination.51 A Norwegian study exploring satisfaction among migrant women in an obstetric hospital setting showed that patients with lowest language proficiency or education were less likely to express dissatisfaction compared with those with better education or a Norwegian husband.52 As many were unaware of their right to receive professional language interpretation, many caregivers’ organised non-professional interpreters—not uncommonly minors—to bridge the language gap. This practice is unsafe and can have severe negative consequences for the patients.53–55 Different studies showed that the use of minors as language brokers can lead to intrafamilial problems, such as a shift of power relations and a reversal of roles, or can be associated with negative emotions on the part of the minors.56 57 In the USA, language interpretation provided by minors is also legally prohibited by Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act.58 These findings highlight that organisation of language interpretation should not be considered a shared responsibility between caregivers and health workers but must be the full responsibility of health workers. A most recent North American publication described a significant increase of the use of professional language interpretation in a PED over a period of 5 years. The multidimensional strategy included staff education, data feedback, reduction of barriers to interpreter use and improved identification of patient’s favourite language for care.59 Similar long-term strategies may be needed in our research context to achieve comparable results.

One caregiver reported that his/her request to receive professional language interpretation was rejected by health workers, arguing that these services would be too costly. Structural discrimination of immigrant minorities including denial of services has also been described in other studies.60 Improving personal skills and attitudes of staff to identify and counter-act different forms of discrimination and to establish a diversity sensitive institutional culture is, therefore, key when improving the quality of care for these patients.61–63

Other studies also described patients’ expectations as key factor for patient satisfaction. Expectations were shaped by many sociocultural factors and experiences from previous health encounters.64 65 In this study, unmet expectations were mostly due to diverging health concepts and misunderstandings about the patient management and or treatment.

Divergent health concepts shaped by different cultural contexts, for example, about the perceived need for antibiotics are well described and language barriers increased the difficulty to align these as shown in different studies.66 67 Like our findings, a qualitative study from the UK on recent migrants’ health beliefs, values and experiences of healthcare described the transformation of health concepts or at least an agreement on common ground between caregiver and health worker was achieved through effective communication, a trusting relationship and a positive health outcome for the patient. High caregiver satisfaction was the consequence.

All statements describing the relationship with the staff were positive in the interpreter group, suggesting that the organisation of an interpreter and the improved ability to communicate contributed to a trustful relationship. Also in settings with no language barriers, a strong association between patient-centred communication, the patient-provider relationship, and patient satisfaction was found.65 68 69 A Swedish study showed that professional interpreters are associated with the improvement of relationship between the patient and caregivers, the increase of patient safety and patient involvement in care.70 As also described in other studies, respect, friendliness and kindness led to trustful relationships and were described as important reasons for caregivers’ satisfaction with care.71 Complaints about the relationship often derived from misconceptions and misunderstandings. Transcultural communication training enabling health workers to be culturally sensitive, reduce personal assumptions and professionally address and respond to differences in health concepts has proven to reduce misunderstandings and ultimately increase patient satisfaction.61 A Danish study was able to show the correlation of satisfaction with the reason of the emergency department visit, the more urgent the reason, the more satisfied the caregivers and staff.72 Clear communication while managing patients including explanations of the triage system and transparent communication of waiting times are known to increase the satisfaction of patients with LLP and those fluent in the local language alike.73

Strengths and limitations

The greatest limitation of this study was the small number of included caregivers for whom a professional interpreter was used. Although saturation was reached for both groups in the qualitative material, the small number did not allow inferential statistical testing of the quantitative data. The language screening was conducted by phone, which might have led to a slightly different assessment of language proficiency compared with an in-person assessment during the PED visit. Although the language scoring system used in this study has been well established by Goethe Institute, it is designed for the evaluation of day to day language and not specifically validated for the medical context. Although taking place in a healthcare context, this study did not evaluate health workers but caregivers, who are not required to know medical terms. Consequently, common language was dominantly used during conversations between caregivers and health workers and, therefore, the use of the Goethe scoring system seemed appropriate.

An important strength of this study was the mixed method approach, allowing to measure the satisfaction with care of LLP-caregivers and other secondary outcome parameters while also allowing to explore underlying reasons for satisfaction. Through the qualitative data, additional important findings were discovered like reasons for limited caregiver self-advocacy for professional language interpretation. The validity of the study increased by the interdisciplinarity of the team, including professional interpreters and study participants in designing and analysing the data.

Conclusion

The use of professional interpreters had a positive impact on the overall satisfaction of LLP-caregivers with emergency care through modulating personal expectations, aligning health concepts and helping to create respectful and trustful caregiver-health worker relationships. LLP-caregivers were not well-positioned to advocate for language interpretation. Healthcare providers must be aware of their responsibility to guarantee good-quality communication to ensure equitable quality of care and patient safety.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating families for taking part in the study and providing feedback. We thank Angelika Louis, head of the interpreting service ‘Comprendi’ and all the intercultural interpreters for interpreting during the interviews, Miss Bohlouli for providing feedback on our interview guideline, Mr Omar and Mr Al Faraj for discussing our results, Diego Lareida and Isabelle Schwerzmann for their help with data collection, Beatrice Lussi for her help in all the administrative tasks and Ante Wind for her linguistic support.

Footnotes

Contributors: MG: conceived the study, conducted the interviews, performed data extraction, performed data analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. NG: conceived the study, performed data analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. SB: conceived the study, conducted the interviews, performed data extraction, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. UF: conceived the study, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. JF and AJ: reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. KK: administrative project leader, conceived the study, supervised analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. JB: scientific project leader and guarantor, conceived the study, supervised analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. KK and JB are joint last authors.

Funding: The study was funded through the ‘Stiftung KinderInsel Bern’ (formerly known as Batzebär foundation). JB received a research grant from the Edwin S.H. Leong Centre for Healthy Children, Toronto, Canada. Award/ Grant number is not applicable.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Ethics Committee of the Canton of Bern on 8 March 2021. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Ramirez D, Engel KG, Tang TS. Language interpreter utilization in the emergency department setting: a clinical review. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2008;19:352–62. 10.1353/hpu.0.0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, et al. Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients Pediatrics 2005;116:575–9. 10.1542/peds.2005-0521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lion KC, Rafton SA, Shafii J, et al. Association between language, serious adverse events, and length of stay among hospitalized children. Hosp Pediatr 2013;3:219–25. 10.1542/hpeds.2012-0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev 2005;62:255–99. 10.1177/1077558705275416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandenberger J, Tylleskär T, Sontag K, et al. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries - the 3C model. BMC Public Health 2019;19:755. 10.1186/s12889-019-7049-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organization GWH . Refugee and migrant health: global competency standards for health workers; 2021.

- 7.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ 1995;152:1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agathe Blaser KG, Spang T. National Programme on Migration and Health. Federal Office of Public Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(FOPH) FOoPH . Community interpreting; 2023. Available: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/gesundheitliche-chancengleichheit/interkulturelles-dolmetschen.html

- 10.Nijman RG, Bressan S, Brandenberger J, et al. Update on the coordinated efforts of looking after the health care needs of children and young people fleeing the conflict zone of Ukraine presenting to European emergency departments-A joint statement of the European society for emergency Paediatrics and the European academy of paediatrics. Front Pediatr 2022;10:897803. 10.3389/fped.2022.897803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations HR . Convention on the rights of the child. 2023. Available: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child

- 12.Gutman CK, Cousins L, Gritton J, et al. Professional interpreter use and discharge communication in the pediatric emergency department. Acad Pediatr 2018;18:935–43. 10.1016/j.acap.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karliner LS, Pérez-Stable EJ, Gregorich SE. Convenient access to professional interpreters in the hospital decreases readmission rates and estimated hospital expenditures for patients with limited English proficiency. Med Care 2017;55:199–206. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, et al. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: a comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:545–53. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellahham S. Communication in health care: impact of language and accent on health care safety, quality, and patient experience. Am J Med Qual 2021;36:355–64. 10.1097/01.JMQ.0000735476.37189.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Achermann AKJ. Übersetzen Im Gesundheitsbereich: Ansprüche und Kostentragung; 2008.

- 17.Blay N, Ioannou S, Seremetkoska M, et al. Healthcare interpreter utilisation: analysis of health administrative data. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:348. 10.1186/s12913-018-3135-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones L, Sheeran N, Pines R, et al. How do health professionals decide whether an interpreter is needed for families in neonatal and pediatric units. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1629–35. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seers K, Cook L, Abel G, et al. Is it time to talk? Interpreter services use in general practice within Canterbury. J Prim Health Care 2013;5:129–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutman CK, Klein EJ, Follmer K, et al. Deficiencies in provider-reported interpreter use in a clinical trial comparing telephonic and video interpretation in a pediatric emergency department. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2020;46:573–80. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundin C, Hadziabdic E, Hjelm K. Language interpretation conditions and boundaries in multilingual and multicultural emergency healthcare. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2018;18:23. 10.1186/s12914-018-0157-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lion KC, Gritton J, Scannell J, et al. Patterns and predictors of professional interpreter use in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics 2021;147:e20193312. 10.1542/peds.2019-3312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips CB, Travaglia J. Low levels of uptake of free interpreters by Australian doctors in private practice: secondary analysis of national data. Aust Health Rev 2011;35:475–9. 10.1071/AH10900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlange SA, Palmer-Wackerly AL, Chaidez V. A narrative review of medical interpretation services and their effect on the quality of health care. South Med J 2022;115:317–21. 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lion KC, Ebel BE, Rafton S, et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention to increase use of telephonic interpretation. Pediatrics 2015;135:e709–16. 10.1542/peds.2014-2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buser S, Gessler N, Gmuender M, et al. The use of intercultural interpreter services at a pediatric emergency department in Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22. 10.1186/s12913-022-08771-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeheskel A, Rawal S. “Exploring the 'patient experience' of individuals with limited English proficiency: a scoping review”. J Immigr Minor Health 2019;21:853–78. 10.1007/s10903-018-0816-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zamor RL, Vaughn LM, McCann E, et al. Perceptions and experiences of latinx parents with language barriers in a pediatric emergency department: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:1463. 10.1186/s12913-022-08839-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaeger FN, Pellaud N, Laville B, et al. Barriers to and solutions for addressing insufficient professional interpreter use in primary healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:753. 10.1186/s12913-019-4628-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pérez-Stable EJ, El-Toukhy S. Communicating with diverse patients: how patient and clinician factors affect disparities. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:2186–94. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinberg EM, Valenzuela-Araujo D, Zickafoose JS, et al. “The "battle" of managing language barriers in health care”. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2016;55:1318–27. 10.1177/0009922816629760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swiss health network for equity. 2023. Available: https://health-equity-network.ch/

- 33.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–56. 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dowding D. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences John W. Creswell, Ann Carroll Klassen, Vicki L. Plano Clark, Katherine Clegg Smith for the office of behavioral and social sciences research; qualitative methods overview Jo Moriarty. Qualitative Social Work 2013;12:541–5. 10.1177/1473325013493540a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castro FG, Kellison JG, Boyd SJ, et al. A methodology for conducting integrative mixed methods research and data analyses. J Mix Methods Res 2010;4:342–60. 10.1177/1558689810382916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hadi MA, Alldred DP, Closs SJ, et al. Mixed-methods research in pharmacy practice: basics and beyond (part 1). Int J Pharm Pract 2013;21:341–5. 10.1111/ijpp.12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussein A. The use of triangulation in social sciences research: can qualitative and quantitative methods be combined? JCSW 2009;4:106–17. 10.31265/jcsw.v4i1.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thurmond VA. The point of triangulation. J Nurs Scholarsh 2001;33:253–8. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research: sage publications; 2017.

- 40.Ridde V, Olivier de Sardan J-P. A mixed methods contribution to the study of health public policies: complementarities and difficulties. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15 Suppl 3:1–8. 10.1186/1472-6963-15-S3-S7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S-YD, Iott B, Banaszak-Holl J, et al. Application of mixed methods in health services management research: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev 2022;79:331–44. 10.1177/10775587211030393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.WSLHD . Assessing the need for an interpreter. 2023. Available: https://www.wslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/Health-Care-Interpreter-Service-/Assessing-the-need-for-an-Interpreter

- 43.Goethe-Institut . Course levels - German courses and German exams. 2023. Available: https://www.goethe.de/en/spr/kup/kon/stu.html

- 44.Creswell JW, Zhang W. The application of mixed methods designs to trauma research. J Trauma Stress 2009;22:612–21. 10.1002/jts.20479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.RUTSCHMANN O-T, SIEBER R-S, HUGLI O-W. Recommandations de la société suisse de médecine D'Urgence et de Sauvetage pour le triage Dans LES services D'Urgences Hospitaliers en Suisse. Bull Med Suisses 2009;90:1789–90. 10.4414/bms.2009.14760 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis - theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution; 2014.

- 47.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018;52:1893–907. 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al Shamsi H, Almutairi AG, Al Mashrafi S, et al. Implications of language barriers for healthcare: a systematic review. Oman Med J 2020;35:e122. 10.5001/omj.2020.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, et al. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res 2007;42:727–54. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okrainec K, Miller M, Holcroft C, et al. Assessing the need for a medical interpreter: are all questions created equal J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:756–60. 10.1007/s10903-013-9821-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health 2000;90:1212–5. 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bains S, Sundby J, Lindskog BV, et al. Satisfaction with maternity care among recent migrants: an interview questionnaire-based study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e048077. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bischoff A, Loutan L. Interpreting in Swiss hospitals. INTP 2004;6:181–204. 10.1075/intp.6.2.04bis [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen S, Moran‐Ellis J, Smaje C. Children as informal interpreters in GP consultations: pragmatics and ideology. Sociol Health Illn 1999;21:163–86. 10.1111/1467-9566.00148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meyer B, Pawlack B, Kliche O, eds. Family interpreters in hospitals: Good reasons for bad practice? 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Banas JR, Ball JW, Wallis LC, et al. The adolescent health care broker-adolescents interpreting for family members and themselves in health care. J Community Health 2017;42:739–47. 10.1007/s10900-016-0312-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orellana MF, Dorner L, Pulido L. “Accessing assets: immigrant youth's work as family translators or "para-phrasers"” Social Problems 2003;50:505–24. 10.1525/sp.2003.50.4.505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Secretary UDoCOo . Federal register. n.d.

- 59.Hartford EA, Rutman LE, Fenstermacher S, et al. Improving and sustaining interpreter use over 5 years in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics 2023;151. 10.1542/peds.2022-058579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pollock G, Newbold B, eds. Perceptions of Discrimination in Health Services Experienced by Immigrant Minorities in Ontario. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taylor C, Benger JR. Patient satisfaction in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2004;21:528–32. 10.1136/emj.2002.003723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boudreaux ED, O’Hea EL. Patient satisfaction in the emergency department: a review of the literature and implications for practice. J Emerg Med 2004;26:13–26. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2003.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health 2017;137:89–101. 10.1177/1757913916634136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lakin K, Kane S. Peoples’ expectations of healthcare: a conceptual review and proposed analytical framework. Soc Sci Med 2022;292:114636. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larson E, Sharma J, Bohren MA, et al. When the patient is the expert: measuring patient experience and satisfaction with care. Bull World Health Organ 2019;97:563–9. 10.2471/BLT.18.225201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Özcebe H, Üner S, Karadag O, et al. Perspectives of physicians and pharmacists on rational use of antibiotics in Turkey and among Turkish migrants in Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands: a qualitative study. BMC Prim Care 2022;23:29. 10.1186/s12875-022-01636-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Herrero-Arias R, Diaz E. A qualitative study on the experiences of Southern European immigrant parents navigating the Norwegian healthcare system. Int J Equity Health 2021;20:42. 10.1186/s12939-021-01384-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:755–61. 10.1007/s11606-016-3597-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Drossman DA, Chang L, Deutsch JK, et al. A review of the evidence and recommendations on communication skills and the patient-provider relationship: a Rome foundation working team report. Gastroenterology 2021;161:1670–88. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Granhagen Jungner J, Tiselius E, Blomgren K, et al. Language barriers and the use of professional interpreters: a national multisite cross-sectional survey in pediatric oncology care. Acta Oncol 2019;58:1015–20. 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1594362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brandenberger J, Sontag K, Duchêne-Lacroix C, et al. Perspective of asylum-seeking caregivers on the quality of care provided by a Swiss paediatric hospital: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e029385. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mygind A, Norredam M, Nielsen AS, et al. The effect of patient origin and relevance of contact on patient and caregiver satisfaction in the emergency room. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:76–83. 10.1177/1403494807085302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee S, Groß SE, Pfaff H, et al. Waiting time, communication quality, and patient satisfaction: an analysis of moderating influences on the relationship between perceived waiting time and the satisfaction of breast cancer patients during their inpatient stay. Patient Educ Couns 2020;103:819–25. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-077716supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.