Abstract

Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes triggers oxygen-dependent and -independent mechanisms of potentially cidal outcome. Nevertheless, no factor or process has yet been singled out as being borreliacidal. We have studied the B. burgdorferi-killing ability of the myeloperoxidase-H2O2-chloride system and that of primary and secondary granule components in an in vitro assay. We found that neither secondary granule acid extracts nor the chlorinating system could kill these microorganisms, while primary granule extracts were effective. The Borrelia-killing factor was purified to homogeneity and demonstrated to be elastase. Its cidal activity was found to be independent of its proteolytic activity.

Borrelia burgdorferi is the causative agent of Lyme disease, a multisystemic and chronic tick-borne spirochetosis characterized by a transient initial rash and erythema migrans, followed by an inflammatory process at the level of the joints, nervous system, and heart (5). Phagocytes are the cells primarily involved in first-line host defenses against bacterial pathogens. A dense infiltrate of mature neutrophils has been found at the site of tick bites (11). However, knowledge about the interaction between B. burgdorferi and phagocytes is fragmentary. These microorganisms are internalized by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) and monocytes-macrophages even during the preimmune phase of infection (1, 2, 24, 29). In fact, immune opsonization of B. burgdorferi is not essential, although it facilitates its uptake (1, 2, 24). Spirochetes are engulfed by conventional or coiling phagocytosis (25) and in either case are finally found inside closed phagosomes, where structural alterations of the microorganisms are apparent on microscopical observation (2).

The bactericidal mechanisms activated during engulfment include the generation of oxygen metabolites and the release of granule proteins into the phagocytic vacuole. The primary granule enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO) catalyzes the formation of potentially cidal active chlorine compounds. Moreover, 10 other neutrophil granule proteins and peptides with cidal activity of their own have been identified and found to differ in both molecular characteristics (size and density of positive charges) and target specificities (14).

Regarding the killing of B. burgdorferi, it is still unclear which neutrophil product(s) is toxic. Upon ingestion of the spirochete, a respiratory burst, which does not seem to be essential for the intracellular killing of borreliae, is induced (4, 24). This is suggested by the fact that both mouse macrophages partially inhibited in the capacity to generate NO and oxygen radicals and human neutrophils from patients with chronic granulomatous disease, totally unable to produce superoxide anion and derivatives, retain killing activity toward the spirochete (19, 24). These observations indicate that oxygen-independent mechanisms may be particularly relevant to the killing of B. burgdorferi. Whereas low-molecular-mass neutrophil granule peptides such as bactenecins and defensins have proved ineffective (21, 26), the possible role of other granule proteins has not yet been ascertained. Preliminary work performed in our laboratory indicated that acid extracts from human neutrophil granules kill borreliae (21), an observation that has been the basis of the studies reported here.

This work describes the identification of a primary granule protein as the only component of human neutrophil granules that is responsible on its own for the killing of B. burgdorferi. The cidal activity of this protein has been characterized in some detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture.

Borrelia strain BITS, belonging to the species Borrelia garinii (B. burgdorferi sensu lato), was isolated from Ixodes ricinus and subcultured every fifth day. This strain was used to identify borreliacidal activities throughout the protein purification procedures. The virulent strain Tirelli (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto) used in some experiments was isolated from an infected patient and used at passage 2. Both strains were cultured at 34°C in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly medium (BSK) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in a standard air incubator.

Escherichia coli K-12 (strain AB 1157) and Streptococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Overnight cultures were transferred to fresh medium and grown at 37°C until mid- to late logarithmic phase.

Bactericidal assays.

Borrelia cultures were harvested during logarithmic growth by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min, at 20°C. Pellets were washed twice with Eagle minimal essential medium (MEM; Sigma) supplemented with 26 mM sodium bicarbonate (pH 7.8) and resuspended in MEM to a final concentration of 106 bacteria/ml as measured in a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber. Variable amounts of the samples being tested for killing activity were added to 104 to 105 spirochetes, in a final volume of 0.2 ml of MEM, and incubated in a shaking bath for 30 min, at 37°C. Borrelia killing was evaluated by the most-probable-number (MPN) method, using a statistical elaboration described by Meynell and Meynell (16). Briefly, serial 10-fold dilutions were prepared and plated into five microplate wells. The plates were sealed and incubated at 34°C for 7 days, after which the wells were examined for the presence of viable spirochetes by dark-field microscopy. Viability counts were performed in triplicate.

E. coli and S. faecalis cidal assays were performed on bacterial suspensions (106/ml) in Krebs-Ringer phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (KRP), or 20 mM citrate buffer, pH 5.5, as indicated. Samples being tested for killing activity were added to the bacteria, in a final volume of 0.2 ml. After 30 min at 37°C, the number of remaining viable bacteria was evaluated by serial dilutions, plating on LB agar, and finally counting of CFU.

Oxygen-dependent bactericidal activity.

Spirochetes (5 × 103) were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in MEM (which contains 0.126 M chloride) with or without the addition of MPO (0.07 μM) and/or H2O2 (0.33 mM), as indicated. MPO was kindly provided by G. Zabucchi et al. (33). The incubation mixtures were tested for bacterial viability (MPN) as described above. As a positive control, E. coli were treated in the same way, and their viability was measured by determining the number of CFU.

Purification and subcellular fractionation of PMNL.

PMNL were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors as previously described (27). Briefly, buffy coats (Blood Bank, Ospedale Maggiore, Trieste, Italy) were subjected to dextran sedimentation, and the leukocyte-rich supernatants were centrifuged on Lymphoprep (Nyegaard, Oslo, Norway) to separate polymorphonuclear (pellet) from mononuclear (interface) cells. Pellets yielded >95% neutrophils after being subjected to hypotonic shock to eliminate remaining erythrocytes.

PMNL (1 × 109 to 2 × 109) were resuspended in disruption buffer (10 mM piperazine-diethanesulfonic acid [PIPES], 100 mM KCl, 7 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM ATP [pH 7.2]) containing 0.5 mM diisopropylfluorophosphate to a concentration of 108/ml and subjected to nitrogen cavitation for 15 min at 350 lb/in2 on ice (3, 13). EGTA (1.25 mM, final concentration) was then added, and unbroken cells and nuclei were pelleted at 1,000 × g for 5 min. Aliquots of the postnuclear supernatant equivalent to 4 × 108 cells each were loaded on isotonic Percoll density gradients prepared by layering consecutively 2.5, 3, and 3 ml of material with densities of 1.05, 1.08, and 1.12 g/ml, respectively. All Percoll solutions were made up in disruption buffer. Gradients were centrifuged at 50,000 × g (rmax; Beckman SW.41 rotor) for 15 min at 4°C, after which the following fractions were collected manually, from top to bottom: cytosolic, band 1 (plasma membranes and vesicles), band 2 (secondary and gelatinase granules), band 3 (light primary granules), and band 4 (dense primary granules). Bands 1 to 4 were diluted two- to threefold with ice-cold disruption buffer and centrifuged at 40,000 × g (rmax) for 30 min at 4°C. The pellets corresponding to the different subcellular fractions were resuspended with disruption buffer to a final concentration of ca. 109 cell equivalents per ml and were used immediately or kept at −80°C.

Identification of subcellular fractions.

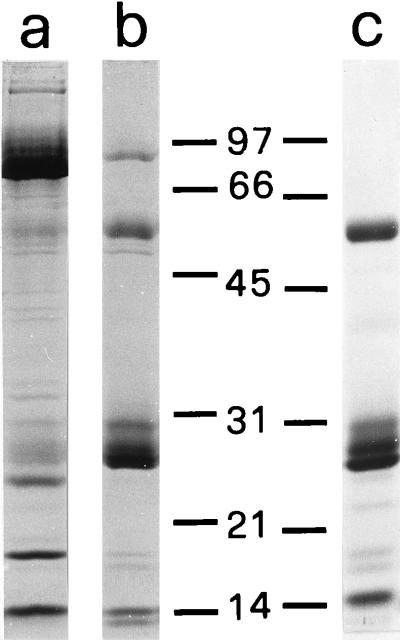

The different fractions were identified by determining the activity of the following marker proteins, as previously described (10): 5′-nucleotidase (AMPase) (plasma membranes), lysozyme (primary and secondary granules), and MPO (primary granules only). Additionally, purified primary and secondary granules were analyzed by Sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and found to be only marginally cross-contaminated (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE profiles of secondary (lane a) and primary (lane b) neutrophil granules and of a borreliacidal primary granule acid extract (lane c). Molecular weights of markers are indicated in thousands.

Preparation of granule extracts.

All procedures were carried out at 0 to 4°C. In the first stage, acid extracts from postnuclear supernatants (total extract) and from purified primary or secondary granules were prepared by overnight extraction with 0.2 M sodium acetate (pH 4.2) with continuous rotation.

Primary granule extracts to be used as starting material for protein purification were obtained by resuspending primary granule pellets with disruption buffer and then subsequently adding Triton X-100 (final concentration, 0.1% [wt/vol]) and sodium acetate (pH 4.2) (final concentration, 0.2 M), so as to achieve 5 × 108 cell equivalents per ml. After 20 to 40 h of extraction with continuous rotation, the extracts were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 45 min. The clear green supernatants were loaded on gel filtration columns as described below.

Isolation of proteins from primary granule extracts. (i) Gel filtration.

Primary granule acid extracts were loaded onto a Sephadex G-75 column (1.4 by 46 cm; total volume 70 ml; bromophenol blue exclusion volume = 96 ± 4 ml) equilibrated with 0.375 M sodium acetate (pH 3.9) at 4°C. Fractions of 1.5 ml were collected throughout at a flow rate of 40 ml/h.

(ii) Ion exchange.

Selected fractions from gel filtration were diluted 15-fold with water and subjected to high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) on Shodex SP columns (Waters, Milford, Mass.) equilibrated with 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5). Elutions were performed with 0 to 1 M NaCl gradients in the same buffer, and A214 was recorded as a function of the retention time (minutes).

SDS-PAGE.

SDS-PAGE was performed with 11% resolving gels, which were stained with Coomassie blue R250.

Protein sequencing.

HPLC fractions with Borrelia-killing activity, which showed a single band with an apparent molecular weight of 27,000 on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3), were subjected to electrophoresis followed by Western blotting on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes as described by Matsudaira (15). The stained, single protein bands were excised from the membranes and directly subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis, which was performed with an Applied Biosystems pulse liquid-phase sequencer (model 477A) equipped with an on-line analyzer (model 120A) of phenylthiohydantoin derivatives of amino acids.

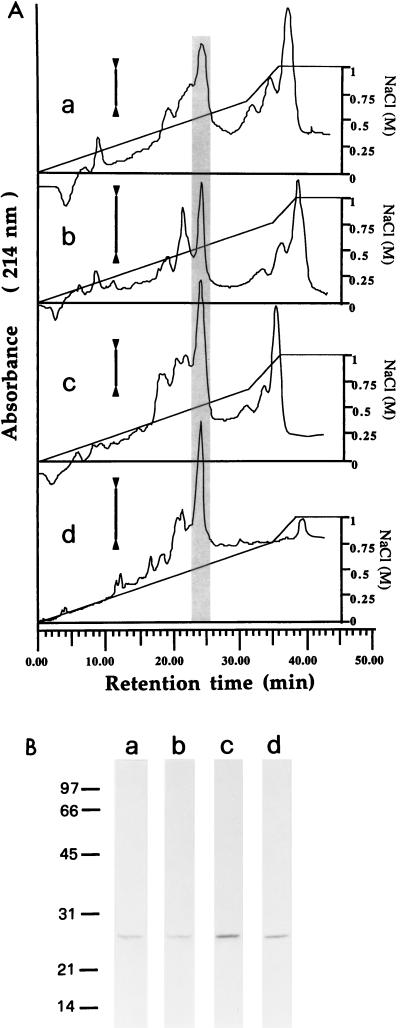

FIG. 3.

HPLC separation of proteins from gel filtration fractions with borreliacidal activity. (A) Fractions 20 (a), 22 (b), 24 (c), and 26 (d) from the G-75 column (Fig. 2) were subjected to cation-exchange HPLC. The vertical bars indicate 0.1 optical density unit at 214 nm. The peaks with borreliacidal activity are highlighted by grey shading. (B) Electrophoretic patterns of the borreliacidal HPLC fractions indicated as shaded areas in the elution profiles shown above. Molecular weights of protein markers are indicated on the left in thousands.

Proteinase activity assays.

Human leukocyte elastase (trypsin-like) activity was measured by using N-methoxysuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val p-nitroanilide (Sigma) as the chromogenic substrate. Human leukocyte cathepsin G (chymotrypsin-like) activity was measured by using N-succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe p-nitroanilide (Sigma) as the substrate. Briefly, samples to be tested were incubated in microplate wells (total volume, 0.2 ml) with 2 mM substrate in 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5). After 30 min at room temperature, the A405 was measured with a Titertek Multiscan MCC/340 (LabSystems, Helsinki, Finland).

RESULTS

Effect of the MPO-H2O2-Cl− bactericidal system.

Since chlorination constitutes a crucially important oxygen-dependent microbicidal strategy employed by neutrophils (12), we tested the efficacy of such system on B. burgdorferi. Table 1 shows the results of a representative experiment (n = 3) which indicate that in the conditions used, the complete system kills E. coli very efficiently but fails to produce a decrease in the number of viable B. burgdorferi.

TABLE 1.

Effects of the MPO-H2O2-Cl− system on the viability of B. burgdorferi and E. coli

| Additiona | Bacterial counts

|

|

|---|---|---|

| B. burgdorferi (104 MPN) | E. coli (CFU) | |

| None | 4.6 | 1.50 × 103 |

| MPO | 3.7 | 1.38 × 103 |

| H2O2 | 4.6 | 1.42 × 103 |

| MPO + H2O2 | 3.6 | <10 |

B. burgdorferi and E. coli cidal assays were performed in MEM, which contains 126 mM Cl−, with the addition of MPO (0.07 μM), H2O2 (0.33 mM), or both, as indicated.

Oxygen-independent killing of borreliae.

As opposed to the oxygen-dependent chlorinating system, neutrophil acid extracts containing proteins from the different types of granules killed B. burgdorferi (Table 2). To establish the source of the killing activity, primary granules were separated from secondary ones by using Percoll gradients. The MPO/lysozyme ratios were 19.1 ± 2.1 and 0.17 ± 0.03 (means ± standard errors, n = 4) for the bands corresponding to primary and secondary granules, respectively, which indicated a good separation. The purity of these granule fractions was additionally assessed by determining their protein patterns on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1, lanes a and b). Borrelia killing activity was found to be present only in acid extracts from primary granules (Fig. 1, lane c; Table 2). As MPO (a major primary granule protein) was not microbicidal towards B. burgdorferi (Table 1), the possibility of other primary granule components being responsible for the killing activity was examined in detail.

TABLE 2.

Oxygen-independent killing of B. burgdorferi

| Acetate (pH 4.2) extract froma: | 104 counts (MPN; mean ± SE [n = 3])a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Time zero | 30 min | |

| Total organelles | 19.0 ± 4.3 | 2.9 ± 2.2 |

| Primary granules | 11.3 ± 3.0 | 4.4 ± 0.3 |

| Secondary granules | 11.3 ± 3.0 | 11.5 ± 1.4 |

Killing assays were performed with 100 μg of extracts from total organelles or 40 μg of extracts from primary or secondary granules.

Separation of primary granule components and determination of their proteolytic and borreliacidal activities.

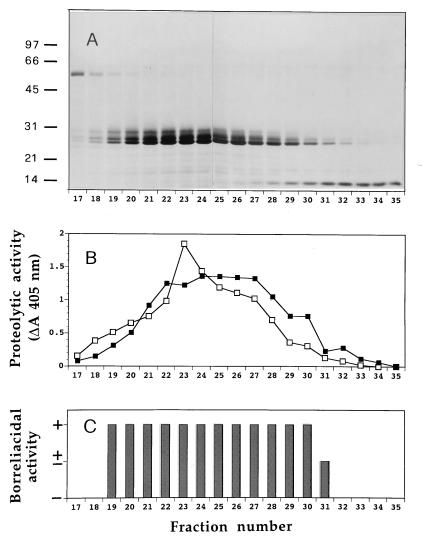

Primary granule extracts were first subjected to gel filtration on Sephadex G-75. Figure 2 (representative of four separate experiments) shows the SDS-PAGE protein pattern, proteolytic activity, and borreliacidal activity of the fractions 17 to 35. None of the preceding fractions killed borreliae or had proteolytic activity. There was a good correspondence between elastase- and cathepsin G-like proteolytic activities and killing of the spirochetes.

FIG. 2.

Gel filtration (Sephadex G-75) of an acid extract from primary granules. (A) SDS-PAGE protein pattern of fractions 17 to 35. Molecular weights of markers are indicated on the left in thousands. (B) Cathepsin G-like (□) and elastase-like (▪) proteolytic activities (10 μl of each fraction), expressed as the change in A405 after 20-min incubations with the specific substrates (see Materials and Methods). (C) Borreliacidal activity of fractions 17 to 35 (10 μl of each), arbitrarily expressed as follows: +, decrease in the number of bacteria of more than 1 logarithm; ±, decrease of less than 1 logarithm; −, no killing.

Four of the active fractions from gel filtration were further analyzed by cation-exchange HPLC at acid pH to establish which proteins have borreliacidal activity and whether this activity is due to the same proteins. The elution patterns show seemingly quantitative differences when the different profiles are compared (Fig. 3A). Nevertheless, only the peak eluting at 0.54 ± 0.02 M NaCl was found to have Borrelia killing activity in all cases, i.e., produced >90% decrease in viability at doses of 0.20 to 0.35 μg per assay. The cidal fractions showed elastase-like activity in the range of 1.4 to 2.6 ΔA405/h/μg of protein but not any cathepsin G-like activity. SDS-PAGE of the borreliacidal peaks showed a single band with an apparent molecular weight of 27,000 in all cases (Fig. 3B). To identify conclusively this protein, Western-blotted bands were analyzed for their N-terminal sequences (Table 3). The results indicated that the borreliacidal protein was leukocyte elastase and not any of the other members of the serprocidin family, namely, azurocidin, proteinase 3, and cathepsin G (8).

TABLE 3.

N-terminal sequence analysis of HPLC-purified borreliacidal protein compared to that of serine protease homologs (serprocidins)

| Protein | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| Borreliacidal protein | I V G G R R A R P X A X P F M V X L X |

| Leukocyte elastase | I V G G R R A R P H A W P F M V S L Q |

| Azurocidin | I V G G R K A R P R Q F P F LA S I Q |

| Cathepsin G | I I G G R ES R P H S R P Y M A Y L Q |

| Proteinase 3 | I V G G HE A Q P H S R P Y M A S I Q |

The 19-amino-acid sequence obtained is compared with that of members of the neutrophil serine protease family (serprocidins). Data are from reference (8). Absence of homology is indicated by underlining of the corresponding amino acids (5 of 19 for azurocidin, 6 of 19 for cathepsin G, and 7 of 19 for proteinase 3).

Characterization of the Borrelia killing activity of elastase.

HPLC-purified elastase was assayed for killing activity toward E. coli, S. faecalis, and B. burgdorferi. There was no effect on the first two bacteria, whereas B. burgdorferi was very efficiently killed (Table 4), even by doses smaller than those used for the other two bacteria (not shown). To exclude the possibility of our laboratory Borrelia strain having become more susceptible to killing, as reported by Moody et al. (20), we tested the cidal activity of our purified elastase on a freshly isolated virulent strain and obtained identical results (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Bactericidal activity of HPLC-purified elastase

| Organism | Bacterial countsa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Without elastase | With elastase | |

| B. burgdorferi BITSb | 3.5 × 105 MPN | 1.6 × 102 MPN |

| B. burgdorferi Tirellic | 3.3 × 105 MPN | 1.3 × 102 MPN |

| E. coli | 1.5 × 103 CFU | 1.6 × 103 CFU |

| S. faecalis | 4.8 × 103 CFU | 4.1 × 103 CFU |

The viability of borreliae, E. coli, and S. faecalis was determined after incubation at pH 7.4 in the absence or presence of 0.4 μg of elastase (HPLC borreliacidal fraction [Fig. 3b]) (results from a representative experiment). The killing of E. coli was also tested at pH 5.5, with the same results as those obtained at pH 7.4 (not shown).

The current laboratory strain.

A virulent isolate from an infected patient (passage 2).

We also investigated the relationship between proteolytic and killing activity of purified elastase. The results shown in Table 5 indicate that (i) heating of elastase at 90°C for 10 min completely abolishes its proteolytic activity but not its Borrelia-killing ability and (ii) treatment with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), an inhibitor of the trypsin-like activity of elastase with no direct effect on the viability of borreliae, does not suppress or decrease the killing activity of elastase. Altogether, these results demonstrate that the cidal activity of elastase is independent of its enzymatic activity.

TABLE 5.

Independence of borreliacidal and proteolytic activities of elastase

| Additiona | Viable borreliaeb (MPN) | Elastase-like activityb,c (ΔA405) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 5.0 × 105 | |

| PMSF | 4.9 × 105 | |

| Elastase | 2.0 × 102 | 0.520 |

| Heated elastase | 2.5 × 102 | 0 |

| Elastase + PMSF | 1.7 × 102 | 0.104 |

Killing and proteolytic assays were performed in the absence or presence of PMSF (1 mM), elastase (0.3 μg of the borreliacidal HPLC peak [Fig. 3b]), or heat-treated (90°C, 10 min) elastase, as indicated.

Results from a representative experiment.

Increase in A405 obtained after 20 min at 37°C.

DISCUSSION

This work describes for the first time the identification and characterization of a B. burgdorferi-killing factor from the human neutrophil. The results demonstrate that (i) oxygen-independent mechanisms are active against these spirochetes, whereas the MPO-H2O2-Cl− system is not effective in conditions in which E. coli is efficiently killed, and (ii) among all granule proteins, only elastase possesses Borrelia-killing activity on its own. This protein, while ineffective toward E. coli and S. faecalis, was found to be active against B. burgdorferi. The killing activity is independent of the proteolytic activity.

Human neutrophils contain in their secretory granules a number of potentially cidal proteins such as cathepsin G, azurocidin, bactericidal permeability-increasing protein, proteinase 3, and defensins (9) which either on their own or, as in the case of MPO, in conjunction with oxygen metabolites (12) are active against different microorganisms. It was somewhat unexpected that among all granule proteins, only elastase was found to kill B. burgdorferi in our experimental conditions. This protein, which consists of 218 amino acid residues and contains two asparagine-linked carbohydrate side chains (28), is a trypsin-like proteolytic enzyme without a clear-cut independent antibacterial activity (6, 31). In fact, only extremely high, arguably nonphysiological concentrations have been reported to kill Capnocytophaga sputigena (17). Nonetheless, a helper role has been attributed to elastase, which appears to potentiate the cidal effect of other active proteins. This has been observed to be the case for the killing of C. sputigena, where very high concentrations of azurocidin become cidal when combined with elastase (18). Interestingly, the interaction between these two granule proteins was found to be enzyme dependent. Similarly, synergy between elastase and MPO or cathepsin G has been reported to result in the killing of E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus, but in this case the potentiating effect was unaffected by heating and therefore unrelated to the proteolytic activity of elastase (23).

We found that elastase was borreliacidal on its own. This was independent from its proteolytic activity, in keeping with what has been reported for other members of the serprocidin family. In fact, cathepsin G kills S. aureus, S. faecalis, E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (22), and Acinetobacter sp. (30) even after being deprived of its enzymatic activity. Additionally, azurocidin is a killing protein yet is not proteolytic (32). This finding suggests that the cidal function of these proteins is unrelated to a degradative activity.

Our results show that borreliae are very sensitive to elastase. In fact, concentrations of 3 to 5 μg/ml are sufficient to kill the microorganisms in the in vitro assay. These amounts are compatible with a physiological situation in which a very small proportion (<0.001%) of the total elastase content of the neutrophil (1.5 μg per 106 cells [8]) would be secreted into spirochete-containing phagocytic vacuoles (ca. 0.2 μm in diameter and 30 μm in length), assuming a minimum of one ingested microorganism per cell. Although we cannot exclude completely the possibility of a minor but very potent contaminant being responsible for the killing of borreliae, this seems unlikely in view of the fact that such a contaminant should have copurified with elastase, i.e., should be similar in molecular size and have the same charge characteristics.

Regarding the possible borreliacidal mechanism of elastase, it may be associated to its interaction with some unknown component of the outer membrane of the spirochetes. This component would be present in both laboratory and freshly isolated, virulent strains, which we have observed to be equally susceptible to elastase (Table 4). Interactions at the level of the outer surface of the microorganisms can be lethal, as demonstrated by the fact that a monoclonal antibody to OspB has been found to be borreliacidal (7). It remains to be established whether elastase acts on borreliae through such a mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by grants from the Italian MURST (40% and 60%) and CNR (CT 95.02202.CT.04).

We are indebted to P. Polverino de Laureto (CRIBI Biotechnology Centre, Padova, Italy) for N-terminal sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banfi E, Cinco M, Perticarari S, Presani G. Rapid flow cytometric studies of Borrelia burgdorferi phagocytosis by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;67:37–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb04952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benach J L, Fleit H B, Habicht G S, Coleman J L, Bosler E M, Lane B P. Interactions of phagocytes with the Lyme disease spirochete: role of the Fc receptor. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:497–507. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borregaard N, Heiple J M, Simons E R, Clark R A. Subcellular localization of the b-cytochrome component of the human neutrophil microbicidal oxidase: translocation during activation. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:52–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cinco M, Murgia R, Perticarari S, Presani G. Simultaneous measurement by flow cytometry of phagocytosis and metabolic burst induced in phagocytic cells in whole blood by Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;122:187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duray P H, Steere A C. Clinical pathologic correlations of Lyme disease by stage. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;539:65–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb31839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elsbach P, Weiss J. Phagocytic cells: oxygen-independent antimicrobial systems. In: Gallin J I, Goldstein I M, Snyderman R, editors. Inflammation: basic principles and clinical correlates. New York, N.Y: Raven Press Ltd.; 1988. pp. 445–470. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escudero R, Halluska M L, Backenson P B, Coleman J L, Benach J L. Characterization of the physiological requirements for the bactericidal effects of a monoclonal antibody to OspB of Borrelia burgdorferi by confocal microscopy. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1908–1918. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1908-1915.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabay J E, Almeida R P. Antibiotic peptides and serine protease homologs in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes: defensins and azurocidin. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabay J E, Scott R W, Campanelli D, Griffith J, Wilde C, Marra M N, Seeger M, Nathan C F. Antibiotic proteins of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5610–5614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia R C, Segal A W. Changes in the subcellular distribution of the cytochrome b-245 on stimulation of human neutrophils. Biochem J. 1984;219:233–242. doi: 10.1042/bj2190233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hödl S, Soyer H P. Dermatopathology of Lyme borreliosis. Acta Dermato-Venereol APA. 1994;3:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klebanoff S J. Phagocytic cells: products of oxygen metabolism. In: Gallin J I, Goldstein I M, Snyderman R, editors. Inflammation: basic principles and clinical correlates. New York, N.Y: Raven Press Ltd.; 1988. pp. 391–444. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klempner M S, Mikkelsen R B, Corfman D H, Andre-Schwartz J. Neutrophil plasma membranes. I. High-yield purification of human neutrophil plasma membrane vesicles by nitrogen cavitation and differential centrifugation. J Cell Biol. 1980;86:21–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehrer R I, Ganz T. Antimicrobial polypeptides of human neutrophils. Blood. 1990;76:2169–2181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsudaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meynell G G, Meynell E. Theory and practice in experimental bacteriology. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1970. pp. 231–232. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyasaki K T, Bodeau A L. In vitro killing of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Capnocytophaga spp. by human neutrophil cathepsin G and elastase. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3015–3020. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3015-3020.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyasaki K T, Bodeau A L. Human neutrophil azurocidin synergizes with leukocyte elastase and cathepsin G in the killing of Capnocytophaga sputigena. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4973–4975. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4973-4975.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modolell M, Schaible U E, Rittig M, Simon M M. Killing of Borrelia burgdorferi by macrophages is dependent on oxygen radicals and nitric oxide and can be enhanced by antibodies to outer surface proteins of the spirochete. Immunol Lett. 1994;40:139–146. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)90185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moody K D, Barthold S W, Terwilliger G A. Lyme borreliosis in laboratory animals: effect of host species and in vitro passage of Borrelia burgdorferi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;43:87–92. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murgia R. B.S. thesis. Trieste, Italy: University of Trieste; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Odeberg H, Olsson I. Antibacterial cationic proteins of human granulocytes. J Clin Invest. 1975;56:1118–1124. doi: 10.1172/JCI108186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odeberg H, Olsson I. Microbicidal mechanisms of human granulocytes: synergistic effects of granulocyte elastase and myeloperoxidase or chymotrypsin-like cationic protein. Infect Immun. 1976;14:1276–1283. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.6.1276-1283.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson P K, Clawson C C, Lee D A, Garlich D J, Quie P G, Johnson R C. Human phagocyte interactions with the Lyme disease spirochete. Infect Immun. 1984;46:608–611. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.2.608-611.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rittig M G, Krause A, Haupl T, Schaible U E, Modolell M, Kramer M D, Lutjen-Drecoll E, Simon M M, Burmester G R. Coiling phagocytosis is the preferential phagocytic mechanism for Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4205–4212. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4205-4212.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scocchi M, Romeo D, Cinco M. Antimicrobial activity of two bactenecins against spirochetes. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3081–3083. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.3081-3083.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Segal A W, Dorling J, Coade S. Kinetics of fusion of the cytoplasmic granules with phagocytic vacuoles in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:42–59. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinha S, Watorek W, Karr S, Giles J, Bode W, Travis J. Primary structure of human neutrophil elastase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2228–2232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szczepanski A, Fleit H B. Interaction between Borrelia burgdorferi and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;539:425–428. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorne K J, Oliver R C, Barrett A J. Lysis and killing of bacteria by lysosomal proteinases. Infect Immun. 1976;14:555–563. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.2.555-563.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasiluk K R, Skubitz K M, Gray B H. Comparison of granule proteins from human polymorphonuclear leukocytes which are bactericidal toward Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4193–4200. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.4193-4200.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilde C G, Snable J L, Griffith J E, Scott R W. Characterization of two azurophil granule proteases with active-site homology to neutrophil elastase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2038–2041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zabucchi G, Menegazzi R, Roncelli L, Bertoncin P, Tedesco F, Patriarca P. Protective and inactivating effects of neutrophil myeloperoxidase on C1q activity. Inflammation. 1990;14:41–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00914028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]