Abstract

Introduction

Rapid population ageing is a demographic trend being experienced and documented worldwide. While increased health screening and assessment may help mitigate the burden of illness in older people, issues such as misdiagnosis may affect access to interventions. This study aims to elicit the values and preferences of evidence-informed older people living in the community on early screening for common health conditions (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, dementia and frailty). The study will proceed in three Phases: (1) generating recommendations of older people through a series of Citizens’ Juries; (2) obtaining feedback from a diverse range of stakeholder groups on the jury findings; and (3) co-designing a set of Knowledge Translation resources to facilitate implementation into research, policy and practice. Conditions were chosen to reflect common health conditions characterised by increasing prevalence with age, but which have been underexamined through a Citizens’ Jury methodology.

Methods and analysis

This study will be conducted in three Phases—(1) Citizens’ Juries, (2) Policy Roundtables and (3) Production of Knowledge Translation resources. First, older people aged 50+ (n=80), including those from traditionally hard-to-reach and diverse groups, will be purposively recruited to four Citizen Juries. Second, representatives from a range of key stakeholder groups, including consumers and carers, health and aged care policymakers, general practitioners, practice nurses, geriatricians, allied health practitioners, pharmaceutical companies, private health insurers and community and aged care providers (n=40) will be purposively recruited for two Policy Roundtables. Finally, two researchers and six purposively recruited consumers will co-design Knowledge Translation resources. Thematic analysis will be performed on documentation and transcripts.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained through the Torrens University Human Research Ethics Committee. Participants will give written informed consent. Findings will be disseminated through development of a policy brief and lay summary, peer-reviewed publications, conference presentations and seminars.

Keywords: Mass Screening, Primary Care, GERIATRIC MEDICINE, Primary Prevention

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of deliberative methods to involve older people (particularly those from diverse, hard to reach groups) and service providers/policymakers in resolving questions around the use of screening among older people.

The Citizens Juries will purposively recruit older people of diverse backgrounds and experiences, thereby addressing a common shortcoming of this method of data collection.

A limitation—the separation of each common health condition into distinct individual juries (rather than considering them together)—was based on the need for clarity and simplicity when presenting the evidence base to jurors.

Introduction

Across the globe, societies are experiencing a period of rapid and unprecedented population ageing.1 Consequently, there has been a growing focus on increased access to primary healthcare for older people, including preventative screening and assessment, with screening here intended to refer to the object of identifying those who have a disease among those who have no symptoms of that disease.2 Misdiagnosis of diseases and conditions is common among older people, with serious consequences for them and the health systems they access.3 A systematic review by Skinner and colleagues revealed rates of overdiagnosis and/or underdiagnosis of at least 5–10% among persons aged 65+ years, for various common health conditions, including cardiovascular disease (CVD) (heart failure, stroke, acute myocardial infarction), dementia and diabetes.3 Overdiagnosis too is problematic for older people. A range of overdiagnosis-related harms have previously been identified in the literature, including self-stigma due to incorrectly diagnosed mild cognitive impairment in dementia prevention.4 Statistics of this nature indicate a critical and urgent need to strike the right balance between overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of various common health conditions, highlighting the importance of appropriate and timely screening.

Clearly, if older people are to receive appropriate, acceptable and timely preventative advice on screening and assessment for common health conditions, then critical attention needs to be given to engaging providers, older people and policymakers in evidence-informed discussions about screening and treatment. Deliberative methods (ie, approaches that bring together a diverse group of community members to engage with evidence on a topic of public concern) provide an opportunity for effective community engagement in evidence-informed policy dialogues on screening. Health and care policymakers are increasingly turning to deliberative and inclusive methodologies to address public policy questions such as whom to screen, and when. A key advantage of deliberative methods is that they allow members of the public to participate directly in key decisions and policies that will impact their daily lives, answering a need that has received growing acknowledgement from policymakers, scientists and consumers alike.5

A deliberative method that has been widely applied in health policy development is Citizens’ Juries.6 Citizens’ Juries are groups inclusive of members of the public, purposively selected to represent their community and who are tasked with deliberating on a jury charge (research question) on a matter of public interest.7 Jurors are usually provided with access to supporting evidence-based resources and expert witness testimonies to support their deliberations and asked to deliver a verdict or make recommendations at the jury end.7 However, few Citizens’ Juries have addressed the views of older people on screening for common health conditions to date. Of studies we identified that have canvassed older people’s views on screening, most have focused on cancer screening,8–14 with none on diabetes, CVD or frailty and a small number on dementia,15–17 highlighting a critical knowledge gap. Additionally, only one-third of all studies identified used a formal Citizens’ Jury format to arrive at their findings (only one of these focusing on dementia), with the remainder using a variety of other less rigorous deliberative methods. A number of studies acknowledged a lack of diversity among participants as a limitation.8 11 12 Lastly, only three of the studies were conducted within Australia.9 11 15 Our study aims to address this critical gap, by canvassing the evidence-informed views of older people on screening for several key common health conditions within the community.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the ‘IMproving the PArticipAtion of older Australians in policy decision-making on common health CondiTions’ (IMPAACT) project is to elicit the values and preferences of evidence-informed older people, including those within under-represented groups, on early screening and diagnosis of several common health conditions (CVD, diabetes, frailty, dementia) within the community. These conditions were chosen as they represent common health conditions experienced by older people, but which have been underexamined through a Citizens’ Jury methodology.

Project objectives include:

To generate recommendations from diverse groups of older people on screening for selected common health conditions within the community via a Citizens’ Jury process;

To obtain feedback from a diverse range of professional groups, older people and industry representatives on the jury findings; and

To co-design (together with a diverse group of older people) Knowledge Translation resources to facilitate the implementation of key recommendations and feedback on screening for common health conditions into research, policy and practice.

Methods and analysis

Participants and study setting

We have elected to set an age limit (50 years and over) for the older population included within our study because this is the population affected by screening for the conditions in question within general practice. We will seek to recruit participants into the study across a wide range of age groups within this category. We will also purposively recruit participants to reflect diversity with respect to gender, socioeconomic status/income, location, culturally and linguistically diverse, gender and sexually diverse, functional ability and frailty level.

Australia has a population of 25 million people, of whom an estimated 9.0 million (35% of the total population) are aged 50 years and over.18 19 The Australian healthcare system is a federated system with responsibility for funding and provision split between the National and State level governments. A universal healthcare scheme (Medicare) provides the main source of funding for hospital services, general practice and medicines.20

Our study is set within the state of South Australia. South Australia offers particular advantages for a study seeking to reflect diversity among its participants, as it is a state characterised by significant heterogeneity with respect to population density, accessibility/remoteness and health service distribution.21

Participants will be free to withdraw at any time during the research project without providing an explanation. Participants can ask the researchers to return or dispose of any data collected from them at any time (unless it is not possible to disaggregate their data from the rest of the data, eg, where a participant has contributed to discussions such as jury deliberations or roundtable proceedings).

Study design

We will apply a participatory design conducted in three Phases, which are aligned with the study objectives stated above:

Phase 1: Conduct Citizens’ Juries on screening for common health conditions within the community,

Phase 2: Conduct Policy Roundtables on screening for common health conditions within the community, and

Phase 3: Co-design Knowledge Translation (KT) resources for input into research, policy and practice.

The study will be carried out between November 2022 and January 2025.

Phase 1: Citizens’ Juries on screening for common health conditions within the community

We will conduct four Citizens’ Juries with older people aged 50 years and above, each one specific to a different common health condition (ie, CVD, diabetes, frailty or dementia). The sample size for the juries will be based on prior research, suggesting approximately 20 participants in each group.22 All participants will provide fully informed consent.

Inclusion criteria for the Citizens’ Juries will be residents of South Australian aged 50 years or over; able to effectively conduct a conversation in English; able to provide fully informed consent. Exclusion criteria for the Citizens’ Juries will be: previously or currently employed as a doctor or nurse in general practice; are a close contact of the research team. For individual juries, participants will be excluded if they are a close contact/relation of another participant attending the same jury; and/or diagnosed with the specified condition that is the subject of that jury.

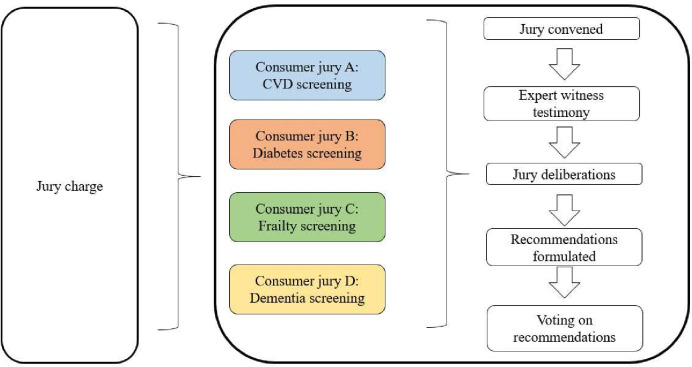

The jury charge (research question) is shown in box 1 and has been developed with reference to other Citizens’ Juries conducted within Australia.6 23 Jury charges will be adapted to reflect the nominated condition for each respective jury and will be refined in consultation with the Project Advisory Group before commencement of the juries. Expert witnesses will be identified through the extended networks of the research team, and will be nationally/internationally recognised experts in their field (with the exception of lived experience witnesses, who will be defined as consumers aged 50 years and over with lived experience of the condition). A depiction of the Phase 1 Citizens’ Jury process is shown in figure 1.

Box 1. Jury charge.

The jury charge (ie, the research question the jury will be asked to consider) will be adapted for each of four juries, each focusing on a different age-related condition (cardiovascular, diabetes, frailty, dementia). The jury charge is:

Under what circumstances should screening be provided for this condition within general practice?

Further questions for the jury to consider over the course of the 2-day programme and which may guide the development of recommendations include:

What benefits and harms might arise from screening?

How could harms be addressed?

Should there be age limits on screening?/When should screening be provided?

Who should provide screening?

Where should screening be provided?

Figure 1.

Overview of Citizens’ Jury process. Source: Adapted from Crotty et al 2020. CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Recruitment of jurors

Recruitment into the study will be via self-selection. The opportunity to participate in the study will be promoted to selected community and consumer organisations via electronic newsletters, print flyers and social media posts targeting subscribers/members aged 50+ years in South Australia. Community groups will be selected to target culturally diverse, gender diverse and rural populations.

Those participants expressing potential interest in the project will be verbally consented for participation with an initial screening survey (online supplemental file 1), to be administered via telephone. Responses to this survey will be assessed against the inclusion criteria and project requirements and those deemed eligible will be mailed/emailed a participant information and consent form. Ineligible participants will be informed by email or post. Participants will be given 2 weeks to consider participation, after which time they will followed-up with a phone call. Those willing will provide written informed consent for participation in Phase 1.

bmjopen-2023-075501supp001.pdf (62.3KB, pdf)

Citizens’ Jury process

We will ask jurors to attend a 2-day workshop. In the week prior to attending the workshops, jurors will receive an information pack containing logistical details for the workshop, guidance as to what to expect regarding the jury process, guidelines for participation, agenda and objectives of the workshop, introductory background materials to support the expert witness testimonies, questions for consideration by participants and an evaluation sheet.6 They will also be asked to complete a short survey with demographic details. An independent facilitator will facilitate all juries.

The Citizens’ Juries will follow standard procedures for this method.23 Expert and consumer witnesses (consumers with lived experience of the condition and/or their proxies) will be identified directly through the professional networks of the researchers and secured by the project management team prior to the commencement of Phase 1.23

On the first day, jurors will hear live expert witness evidence, which will be followed by an interactive session with the witness panel to allow jurors to ask questions. On the second day, the jury will have allocated time to discuss the jury charge, formulate recommendations and conduct discussions within their jury group. During the closing session of the jury, jurors will be asked to vote on the recommendations generated by the group. Voting will be conducted in an open manner and juror votes will be known to the rest of the group.

At the conclusion of each jury, participants will participate in a short debriefing session and complete a project-specific evaluation form.6 The form will include Likert-scale ratings (1–7 scale) relating to juror satisfaction with the jury process, including elements such as degree of satisfaction with background material provided, expert witness testimony and time commitment required, along with a small number of open-ended questions to allow jurors to make explanatory comments or suggestions. The evaluation data will be used iteratively to improve the implementation of the juries as they progress, and for overall assessment of the feasibility of our approach at project close.

Phase 2: Policy Roundtables on screening for common health conditions within the community

Following the Citizen’s Jury process, two Policy Roundtables will be convened24 on the theme of ‘Screening for common health conditions in the community’. Roundtables are an engagement tool designed to bring together a range of stakeholders to converse on a topic of interest, the outcome of which should be improved representation of the viewpoints of those who have stakes in the issue under consideration.25 The roundtables will each run over 2 days. The aim of the roundtables will be twofold: (1) encourage evidence-informed dialogue between researchers, older people and policymakers on the subject of screening for common health conditions; and (2) support the translation of findings from the Citizen’s Jury process into research, policy and practice. Roundtables will focus on all the recommendations collectively emerging from the juries in relation to the four identified health conditions.

Recruitment of participants

We will recruit approximately 20 stakeholders to attend each roundtable, to be held in person (or online if COVID-19-related restrictions are in force). One of the key considerations in identifying participants is the question of who would potentially benefit from or be harmed by the implementation of screening. Aside from older people and their carers, it is also important to recognise the commercial interests behind some of the moves towards earlier screening. Consequently, the professional stakeholders identified as a component of this study will include representation from consumers and carers, health and aged care policymakers (State and Federal), general practitioners, practice nurses, geriatricians, allied health practitioners, pharmaceutical companies, private health insurers and community and aged care providers. We will recruit the desired number of participants purposively via direct approach and/or snowball sampling.

Policy Roundtable process

Roundtable participants will be sent an information pack 2 weeks before the event, inclusive of a short survey including demographic information. Each roundtable will be jointly co-chaired by a representative from the research team and a consumer representative,24 while an experienced external facilitator will facilitate group discussions. An invited external speaker will present an overview of the issue of misdiagnosis of common health conditions among older people within Australia. Day 1 sessions will include a contextual overview of each of the four conditions analysed in Phase 1, along with presenting key findings from the condition-specific Citizens’ Juries. Day 2 will focus on deliberative group discussions to consider the findings and generate feedback. A representative from each group will provide detailed feedback to the main group. Each day will conclude with a summary of the main discussion points. At the end of Day 2, participants will be given a short evaluation form to complete. Members of the research team will also be in attendance to observe proceedings and collect observations against a predetermined template.

Phase 3: consumer co-design of Knowledge Translation resources: policy brief and lay summary

The aim of the consumer co-design process will be to develop two KT resources: (1) a policy brief that synthesises the recommendations from the Citizens’ Juries and feedback from Policy Roundtables, and (2) an accompanying lay summary targeted at older people and their families. Within the context of this study, KT is defined to mean the process of closing the gap from knowledge production (eg, through research) to policy and practice.26 Where consumer and/or professional feedback obtained as a result of the jury and roundtable process differs from existing clinical guidelines, these differences will be retained and highlighted within the resources as areas requiring further research and consultation. With respect to co-design, we refer to the process by which end-users of research are meaningfully engaged throughout all stages of research design and implementation.27 The co-design team will comprise of two researchers and six consumer co-researchers (purposively selected with respect to age, gender, income level and ethnicity). Recruitment of participants will be conducted by approaching participants who indicated willingness to take part in further research from the earlier Phases and who meet the needs of this Phase as determined by the research team. The team will be responsible for defining the target audience/s for the recommendations, identifying key messages for translation, designing appropriate KT resources (final format/s to be decided by the co-design team) and developing action and communication plans for dissemination.

We will provide co-design team participants with background material on the aims of the co-design process, methodology and study findings 2 weeks before Phase 3 commencement. Participants will attend three meetings of 2 hours’ duration, an approach which proved feasible in our previous consumer co-design work.28 29 The meetings will be held face-to-face within Adelaide (virtual attendance to be offered if required). An external facilitator will facilitate all co-design meetings. At the initial meeting, the co-design team will be presented with the summary of findings from Phases 1 and 2. At the second and third meetings, the co-design team will be shown interim drafts of the emergent KT resources and asked to provide comments. A small group of stakeholders will review the draft/s before finalisation and provide any further feedback required. The final meeting will also include a reflection on the co-design process among participants and discussion of future correspondence.

Patient and public involvement statement

Our study will be grounded in participatory action research and co-design principles,30 with the intent to meaningfully engage older people at all stages, beginning from project conceptualisation (with the appointment of an older person with extensive experience of co-design processes, as a co-researcher on our project team), through to the design, delivery and ultimately, dissemination of results. Recruitment of participants from diverse backgrounds will be aided by researcher networks and the involvement of a number of aged care and community professionals and services.

Data collection and analysis

A Hansard reporter will transcribe all juries (Phase 1) and roundtables (Phase 2), with backup audio recording using a password-protected late model iPhone. Research team members will also take field notes during the sessions and include these within the analysis, together with participant feedback and evaluations. Documentation used within the workshops will also be analysed. Data will be uploaded and analysed within the latest versions of the Excel and NVivo software packages.

We will adopt a qualitative descriptive approach to analyse data,31 with the aim of understanding the key justifications for the recommendations put forward by jurors and participants. Two independent analysts will first familiarise themselves with the transcripts through repeated readings. The unit of analysis will be at the individual jury/roundtable level. We will code the transcripts and additional documentation inductively according to thematic analysis principles, cross-verifying codes to ensure rigour. We will organise codes into categories, subcategories and candidate themes, refining these in discussion with a third analyst.32

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical and safety considerations

We will support all participants throughout the project to give informed consent, either in written form or verbally (video recorded), dependent on context. Participants will be anonymous in all reporting of the different Phases of the study unless they wish to be identified, for example, as co-designers of the resources in Phase 3. Consumer participants in any Phase of the research will be paid a research honorarium for their time.

The Torrens University Human Research Ethics Committee (approvals 0206, 0238 and 0253) has approved the ethical aspects of this research project.

Dissemination and implementation strategies

Dissemination of the research findings will consist of multiple strategies within an integrated (KT strategy.33 National and international platforms and websites, newsletters for both professionals and older people, journal publication, conferences and a cross-national seminar series will be employed as channels for dissemination. Beyond dissemination, we will also explore and co-develop potential implementation strategies with stakeholders throughout all stages of the project.

Limitations

We acknowledge a number of limitations of the study. First, due to the complexity of the conditions included, we have elected to address them on an individual basis within Phase 1 (the Citizens’ Juries). However, we will aim to synthesise the key findings across each condition in Phase 2, highlighting areas of commonality and difference. A second limitation is the high degree of dependence between the sequential Phases of the project, with the outcomes for each Phase highly dependent on the Phase before it. However, we have endeavoured to mitigate this potential risk by ensuring that Phase 1 is designed to a high standard of quality with reference to established practice for the conduct for Citizens’ Juries, thereby maximising the likelihood that subsequent Phases will eventuate in meaningful outcomes for the project. Further, the project is underpinned by strong governance structures with a comprehensive risk management plan in place to minimise unintended consequences. Last, while we have made efforts to enhance diversity among the participant group, it is not possible to represent all aspects of diversity within the participant base.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @mt_lawless, @DrMatthewLeach, @Mandy_Archibald

Contributors: RCA is the principal investigator for the project and was responsible for the initial conception of the study, and for coordination of study design and manuscript development. CJH contributed to study design, drafted the initial version of the manuscript and contributed to drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. ML, AB-M, RV, JB, SS, VC, MJL, DT, MT and ED are chief investigators on the project and made substantive contributions to development of the study design and to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. LW, MA, HMO'R, KW and AC are associate investigators on the project and made substantive contributions to development of the study design and to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project is funded via National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) Dementia, Ageing and Aged Care Mission 2021, Grant ID #2016140. SS is supported by an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship, Grant ID #472662.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) . Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report; 2020. 1–24.

- 2.Wilson JMG, Jungner G. Principles and practice of screening for disease. 1968.

- 3.Skinner TR, Scott IA, Martin JH. Diagnostic errors in older patients: a systematic review of incidence and potential causes in seven prevalent diseases. IJGM 2016;9:137. 10.2147/IJGM.S96741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maki Y. Reconsidering the overdiagnosis of mild cognitive impairment for dementia prevention among adults aged ≥80 years. J Prim Health Care 2021;13:112–5. 10.1071/HC20115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abelson J, Forest P-G, Eyles J, et al. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:239–51. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00343-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scuffham PA, Krinks R, Chalkidou K, et al. Recommendations from two citizens’ juries on the surgical management of obesity. Obes Surg 2018;28:1745–52. 10.1007/s11695-017-3089-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Street J, Duszynski K, Krawczyk S, et al. The use of citizens’ juries in health policy decision-making: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2014;109:1–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abelson J, Tripp L, Sussman J. I just want to be able to make a choice: results from citizen deliberations about mammography screening in Ontario, Canada. Health Policy 2018;122:1364–71. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas R, Glasziou P, Rychetnik L, et al. Deliberative democracy and cancer screening consent: a randomised control trial of the effect of a community jury on men’s knowledge about and intentions to participate in PSA screening. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005691. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005691 Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84920742506&doi=10.1136%2Fbmjopen-2014-005691&partnerID=40&md5=c428e5b6a8d16ae19b283368ce51c89d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosconi P, Colombo C, Satolli R, et al. Involving a citizens’ jury in decisions on individual screening for prostate cancer. PLoS One 2016;11. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84954528798&doi=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0143176&partnerID=40&md5=7ee3a66e8a504826a38be48ad82a85a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degeling C, Barratt A, Aranda S, et al. Should women aged 70-74 be invited to participate in screening mammography? A report on two Australian community juries. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021174. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baena-Cañada JM, Luque-Ribelles V, Quílez-Cutillas A, et al. How a deliberative approach includes women in the decisions of screening mammography: a citizens’ jury feasibility study in Andalusia, Spain. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019852. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholls SG, Wilson BJ, Craigie SM, et al. Public attitudes towards genomic risk profiling as a component of routine population screening. Genome 2013;56:626–33. 10.1139/gen-2013-0070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholls SG, Etchegary H, Carroll JC, et al. Attitudes to incorporating genomic risk assessments into population screening programs: the importance of purpose, context and deliberation. BMC Med Genomics 2016;9:25. 10.1186/s12920-016-0186-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas R, Sims R, Beller E, et al. An Australian community jury to consider case‐Finding for dementia: differences between informed community preferences and general practice guidelines. Health Expect 2019;22:475–84. 10.1111/hex.12871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SYH, Uhlmann RA, Appelbaum PS, et al. Deliberative assessment of surrogate consent in dementia research. Alzheimers Dement 2010;6:342–50. 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vries R, Stanczyk A, Wall IF, et al. Assessing the quality of democratic deliberation: a case study of public deliberation on the ethics of surrogate consent for research. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1896–903. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Population 2022. n.d. Available: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population

- 19.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Older Australians, demographic profile. 2022. Available: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians/contents/demographic-profile

- 20.Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care . The Australian health system. Available: https://www.health.gov.au/about-us/the-australian-health-system [Accessed 02 Dec 2022].

- 21.Archibald MM, Ambagtsheer R, Beilby J, et al. Perspectives of frailty and frailty screening: protocol for a collaborative knowledge translation approach and qualitative study of stakeholder understandings and experiences. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:87. 10.1186/s12877-017-0483-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krinks R, Kendall E, Whitty JA, et al. Do consumer voices in health-care citizens’ juries matter. Health Expect 2016;19:1015–22. 10.1111/hex.12397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crotty M, Gnanamanickam ES, Cameron I, et al. Are people in residential care entitled to receive rehabilitation services following hip fracture? Ciews of the public from a citizens’ jury. BMC Geriatr 2020;20:172. 10.1186/s12877-020-01575-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romich J, Fentress T. The policy roundtable model: encouraging scholar–practitioner collaborations to address poverty-related social problems. J Soc Serv Res 2019;45:76–86. 10.1080/01488376.2018.1479343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damani Z, MacKean G, Bohm E, et al. The use of a policy dialogue to facilitate evidence-informed policy development for improved access to care: the case of the winnipeg central intake service (WCIS). Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:78. 10.1186/s12961-016-0149-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ 2009;181:165–8. 10.1503/cmaj.081229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co-design in health: a rapid overview of reviews. In: Health Research Policy and Systems 18. BioMed Central Ltd, 2020: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Archibald M, Ambagtsheer R, Lawless MT, et al. Co-designing evidence-based videos in health care: a case exemplar of developing creative knowledge translation “evidence-experience” resources. Int J Qual Methods 2021;20. 10.1177/16094069211019623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawless M, Wright-Simon M, Pinero de Plaza MA, et al. My wellbeing journal: using experience-based co-design to improve care planning for older adults with multi morbidity. The JHD 2022;7:494–505. 10.21853/JHD.2022.165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyd H, McKernon S, Mullin B, et al. Improving healthcare through the use of co-design. N Z Med J 2012;125:76–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Archibald MM, Lawless MT, Ambagtsheer RC, et al. Understanding consumer perceptions of frailty screening to inform knowledge translation and health service improvements. Age Ageing 2021;50:227–32. 10.1093/ageing/afaa187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitson A, Powell K, Hoon E, et al. Knowledge translation within a population health study: how do you do it. Implement Sci 2013;8:54. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-075501supp001.pdf (62.3KB, pdf)