Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To understand fellowship program directors’ (FPDs) perspectives on facilitators and barriers to using entrustable professional activities (EPAs) in pediatric subspecialty training.

METHODS

We performed a qualitative study of FPDs, balancing subspecialty, program size, geographic region and current uses of EPAs. A study coordinator conducted 1-on-1 interviews using a semistructured approach to explore EPA use or nonuse and factors supporting or preventing their use. Investigators independently coded transcribed interviews using an inductive approach and the constant comparative method. Group discussion informed code structure development and refinement. Iterative data collection and analysis continued until theoretical sufficiency was achieved, yielding a thematic analysis.

RESULTS

Twenty-eight FPDs representing 11 pediatric subspecialties were interviewed, of whom 16 (57%) reported current EPA use. Five major themes emerged: (1) facilitators including the intuitive nature and simple wording of EPAs; (2) barriers such as workload burden and lack of a regulatory requirement; (2) variable knowledge and training surrounding EPAs, leading to differing levels of understanding; (3) limited current use of EPAs, even among self-reported users; and (4) complementary nature of EPAs and milestones. FPDs acknowledged the differing strengths of both EPAs and milestones but sought additional knowledge about the value added by EPAs for assessing trainees, including the impact on outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Identified themes can inform effective and meaningful EPA implementation strategies: Supporting and educating FPDs, ongoing assessment of the value of EPAs in training, and practical integration with current workflow. Generating additional data and engaging stakeholders is critical for successful implementation for the pediatric subspecialties.

Keywords: Entrustable Professional Activities, implementation, fellowship, assessment

Introduction

As medical education has shifted toward an outcomes-based framework of competency-based medical education (CBME), considerable attention has been focused on developing and implementing comprehensive assessment methods and tools.1-4 Within the United States Graduate Medical Education (GME) system, the current approach to assessment is milestone-based, with mandatory reporting to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).5,6 Milestones are skills, knowledge, and behaviors that represent performance levels along a developmental continuum. 7 However, competencies and milestones require clinical context and are not designed to be used for assessment in isolation. One way to provide a clinical context for competencies and milestones is through Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs).8-10 EPAs, which have been developed and studied in multiple countries and for numerous specialties, 11 represent observable and measurable activities essential to the profession. 12 These activities require the successful integration of behaviors and competencies by an individual learner. Learners’ ability to successfully execute an EPA is assessed using a scale delineating required levels of supervision, with the ultimate goal of achieving unsupervised practice. 12 Many faculty find using EPAs more intuitive and meaningful than context-independent milestone-based assessments, which ultimately leads to more effective learner assessments. 13

Almost a decade ago, education leaders from the pediatric subspecialty community, in collaboration with the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), developed a set of common EPAs for all pediatric subspecialties and a set of EPAs for each specific subspecialty. 14 The common EPAs describe activities of all pediatric subspecialists whereas subspecialty-specific EPAs describe activities essential to that particular discipline. The ABP plans to incorporate these EPAs into their initial certification process by 2028. 15 Despite validity evidence for the use of EPAs for assessment and their perceived value for assessment purposes, EPAs are not yet uniformly used across pediatric fellowship programs in the United States.16,17 A number of studies have reported on the implementation of EPAs into curricular designs in residency programs, but none have focused on implementation of EPAs for pediatric subspecialty training.18,19 Effective implementation of new or different practices within education, like EPAs, requires a thoughtful and collaborative approach with relevant stakeholders and an understanding of the facilitators and barriers to their implementation.20-22 One of the key stakeholders involved in the implementation of EPAs is the fellowship program director (FPD). FPDs are the frontline leaders tasked with local implementation of the EPAs. Thus, their perspectives may be valuable to the pediatric community.

Few studies have been published about the implementation of EPAs in the United States or abroad.18,23-25 While early adopters may champion the use of EPAs, a deeper understanding of the perceived role of EPAs within pediatric subspecialties is important as the field of pediatrics continues the transition toward broader implementation of EPA-based assessment. Despite described guidelines for successful implementation by medical education experts, 26 it is imperative to explore and evaluate how EPA implementation has been adopted and adapted in a variety of settings. 24 To advance understanding of EPA implementation within pediatric subspecialty programs, we performed a qualitative study with FPDs across the United States. The primary aims were to understand the facilitators and barriers to implementing the EPAs to assess pediatric subspecialty fellows, how EPAs were currently being used, and FPD perspectives on the value added by EPAs for fellow assessment.

Methods

Study design, strategy and data collection

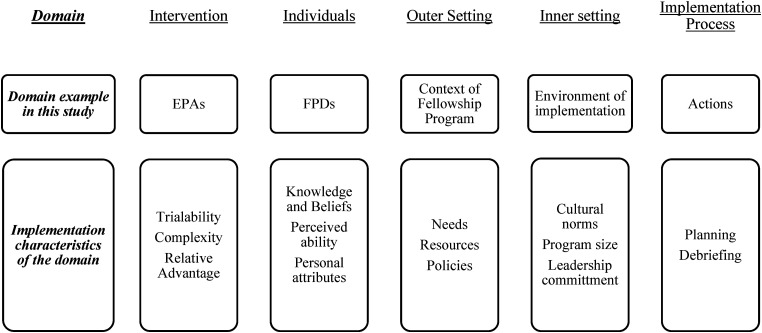

We performed a qualitative study of subspecialty FPDs, using an inductive approach with a constant comparative method to yield thematic analysis. 27 We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) as the overarching framework for the study and interview guide as we sought to understand the implementation process for EPAs. 28 We explored each of the 5 domains (intervention characteristics, characteristics of individuals involved, the outer setting, the inner setting, and the process of implementation) through the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Domains of the consolidated framework for implementation research with study-specific examples.

The study team included 8 members of the Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) Subspecialty Pediatrics Investigator Network (SPIN), representing 7 different subspecialties, and a dedicated study coordinator who conducted the interviews. 29 The APPD SPIN team members all had significant knowledge and experience with training pediatric subspecialty fellows and GME but variable personal experience with EPA implementation. One member (MLL) with expertise in qualitative research led the team and provided training to both the study coordinator and other research team members.

We used purposeful and snowball sampling methods to identify FPDs within various pediatric subspecialties who were aware of and willing to discuss the EPAs. Participants had to be willing to be interviewed and recorded; there were no other exclusion criteria. Potential participants were recruited through email sent to all FPDs and in-person conversations by APPD SPIN Steering Committee members. Prior to the interview, we collected information from 42 FPD volunteers through close-ended questions about their pediatric subspecialty, number of years as FPD, geographic region, size of the fellowship program, and self-rating of EPA understanding. Participants were chosen to balance FPDs from different subspecialties, program size, geographic region and current uses of EPAs. From November 2019 to September 2020, the APPD SPIN study coordinator conducted semi-structured in-depth 1:1 interviews. Participants were divided into 2 groups based on their self-reported use of EPAs as users and nonusers. EPA nonusers were included so as not to overlook valuable insights and understanding regarding rationale for not implementing EPAs or failed implementation experiences and identify specific barriers unique to this group. For each group, a separate semi-structured interview guide was created with questions mapped to the relevant CFIR domains. (Supplemental Appendix 1) We piloted interview questions among APPD SPIN members, conducted 4 pilot interviews, and iteratively revised the interview guide as needed. 30 Data from pilot interviews were not included in the analysis. Participants who completed an interview were offered a $25 gift card for their time. We conducted interviews until we reached theoretical sufficiency, or a satisfactory conceptual depth to allow for thematic analysis. 31

We conducted interviews via a teleconferencing platform in which audio, but not video, was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service (Rev.com). One person conducted all interviews, and this individual was located at the Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. Each participant received copies of both the common and subspecialty-specific EPAs prior to the interview. We asked EPA users to describe their current use of EPAs and the implementation process, and EPA nonusers about their understanding of EPAs; both were asked about potential facilitators and barriers to EPA use. Both groups were asked about fellow evaluation processes, the concept of entrustment, and their perceptions around the value of EPAs, including the relationship to milestones. We modified the interview guide after the first and second rounds of analysis. To enhance the trustworthiness of the data, we created an audit trail to document any changes to the initial interview guide as well as the development of the coding structure.

Analyses

Interview audio-files and transcripts of the interviews served as our data sources. To avoid contamination and bias, 4 authors independently analyzed and coded data for the EPA users and 3 different authors coded data for the EPA nonusers. One additional author (MLL) coded all transcripts. We used inductive analysis grounded in the views of the participants, as opposed to testing/confirming theory.32,33 First, team members read through transcripts to gain an overall understanding. Each document was then reviewed line by line and codes (words that act as labels for important concepts) were applied to excerpts of the interview transcripts. The initial code structure for each group was created using the coding data from the first 3 transcripts. The code structure was then iteratively revised with the review of each additional transcript. Each team met to review transcripts and engaged in discussion to attain consensus in coding and assess coder reliability. 30 Related codes were combined into categories which were then developed into themes that described overarching concepts. 32 After the final code structure was established, the transcripts were reviewed and the final codes applied to the data. The teams then met to discuss comparable and contrasting concepts and themes between the 2 groups of participants, a form of investigator triangulation. 34 Dedoose, a qualitative analysis software tool, was used as an organizational tool to support the analysis of data (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC.).

The interview guide and qualitative analysis included secondary objectives to examine the process used by CCCs to assess their fellows and gauging opinions from FPDs about EPAs, particularly around readiness for graduation. These results have been previously published. 13

Ethical approval for this study was obtained by the Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center Human Subjects Committee (IRB number 18CR-31910-01, approved 09/13/2019). The Human Subjects Committee approved the use of verbal consent, and the interviewer maintained a list of those subjects who consented to participate.

Results

We interviewed 28 FPDs representing 11 different subspecialities of differing program size with varying experience as a program director. 13 Among the participants, 16 (57%) self-identified as EPA users. EPA understanding was similar to prior reports 17 ; EPA users were more likely to report an in-depth and expert understanding of EPAs, whereas nonusers reported were more likely to report either unfamiliarity or only a basic understanding of EPAs. FPDs reported a median of 3 fellows in their program and 6 years of experience as program director. Five major themes for EPA implementation emerged from analysis: (1) Facilitators to EPA implementation, (2) barriers to EPA use, (3) role of knowledge dissemination surrounding EPAs, (4) limited use of EPAs, and (5) comparisons between EPAs and milestones. Representative quotes have been included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Major themes and representative quotes.

| Theme | Facilitators of EPA implementation |

| Subtheme: The concept of entrustment is intuitive and easy to understand | “Let's say when I trust this person with my own children doing something related to the specialty … I think it's intuitively much easier to grasp than when you have this long list of qualifiers and milestones.” |

| Subtheme: EPAs more accurately reflect achievements specific to subspecialty | “The EPAs just very concretely describe activities that you expect a person who's going to practice in our specialty to be able to effectively perform without the needs of any supervision, independently. And those that end up being the goal to reach after undergoing training.” |

| Theme | Barriers to EPA use |

| Subtheme: The work involved in implementing a new assessment tool is a significant barrier |

“I don't have enough personal or administrative resources to add the EPAs in.” “Faculty don't have a way to be recognized for most of this work, and it takes time. And so, to convince faculty to take more time out of the other things that they're expected to do to keep their jobs, it's hard to add more things on without more support.” |

| Subtheme: The value of EPAs as an assessment tool is unclear | “Before people are going to care about learning how to use them, they have to be clear on the value. Like what are they for and who's looking at them, and why are they important.” |

| Theme | Knowledge dissemination surrounding EPAs |

| Subtheme: Variability in training experiences surrounding EPAs | “I've read the EPAs and I've looked at the EPA book and I've used the EPAs to do a little faculty development and about how we might want to implement these kinds of things but no, I haven't had any more training that … I might have listened to a presentation or something like that at some point.” |

| Subtheme: EPAs are perceived as an unfinished product |

“If there was a framework of how to actually apply these assessments that was a little more concrete and a guidebook for what to do if you had a fellow with a poor assessment on the EPAs, and there was support through our institution for involving faculty at a greater level in this stuff, then I could see that it could be helpful and useful.” “I think I'd like to understand how they vary from the milestone assessment and if it were a more robust way to help assess their progress and then certainly if that's the movement that they are wanting us to go across the board, I would be happy to implement.” “In other words, in our specialty, have a group of people to pilot the use of the EPAs and then come up with feedback as to whether how helpful they were, what are the things that need to be improved. That's sort of more like a quality improvement type of cycle where we would take these and pilot [with] a small group of people and see what are the things that work okay.” |

| Theme | Limited use of EPAs |

| Subtheme: Current use of EPAs is minimal | “The EPAs are newer to us, and I really just started doing them with this last when we started participating in the current SPIN EPA study.” |

| Subtheme: Endorsement by ACGME/governing bodies/institution important consideration | “Seriously, if it was sent to me by the American Board of Pediatrics every six months just like the milestone requests are, with the template, with the EPA, and the template for evaluating, then I would do it.” |

| Theme | Comparison of EPAs to milestones |

| Subtheme: The ease of use of EPAs compared to Milestones |

“This is just much more straight forward. … in just looking at what the definitions of level one through five are, there's not a lot of room for sort of not understanding what's being stated. It's pretty direct … sometimes where I run into issues with the milestones is what does this really mean? And you know, the wording is very flowery and so it can, you can sometimes get lost and just the amount of reading you need to do. And this is just … It's pretty straightforward.” “I have to admit, there's a number of things on those milestones where even now, I have a hard time saying what they mean. I have a hard time operationalizing them. They are confusing. I think the narrative description above the milestones often say different things, or they mention different aspects, where a particular trainee may be strong on one aspect of that, but not so strong on the other. So, then it leads to confusion as to how one ought to rate somebody along that progress.” |

| Subtheme: The complementary nature of milestones and EPAs | Are you going to be able to trust them? And that to me is the essential question. And I think it's useful to have [EPAs] aligned with the milestones. So if people are having issues, you can go and say, okay, well what are the components of this? For the person that I was having issues with, I actually went back to the whole pediatric milestones document with all 51 of them and … they really got to the issues that we were seeing. So I think it's nice to have both as long as you have an understanding of how they work. |

| Subtheme: The role of governing bodies | “The disadvantage is just to have to do them both in parallel. It makes me crazy. Can't the ACGME and the American Board of Pediatrics get together and put together one assessment tool that encompasses both things?” |

| Subtheme: Perceived value of a tool | “The greatest value of both, whether it's the milestones or the EPA is really, they just stimulate discussion in the CCC. And that's really the heart of it. And that's how I come up with my kind of written comments and that sort of performative feedback that I give during the semi-annual reviews.” |

EPA, Entrustable Professional activities; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; SPIN, Subspecialty Pediatrics Investigator Network.

Facilitators of EPA implementation: Ease of use and perceived relevance of EPAs aid implementation

The overall ease of use and relevance to practice were 2 important facilitators of EPA implementation. FPDs related the intuitive nature of entrustment and the assessment of supervision level to EPA usability. The relevance to subspecialty practice and simplicity of wording for both EPA description and scale of assessment also facilitated ease of use. FPDs described certain EPAs as more highly valued, particularly the subspecialty-specific ones, whereas some common subspecialty EPAs (eg, Contribute to the Fiscally Sound, Equitable, and Collaborative Management of a Healthcare Workplace) were felt to be less important or useful. Furthermore, FPDs believed EPAs accurately reflect activities that are specific to each subspecialty.

Barriers to EPA use: Addressing the perceived value of and effort needed to implement EPAs are important barriers to overcome

The main barriers to EPA implementation included the potential additional workload involved in implementing a new method of assessment, such as the EPAs, and the uncertainty around the value added. Nonusers in particular were unsure how EPAs are distinct from milestones. They also described an unclear rationale for EPAs, both as a general concept and regarding their applicability to trainees. Some FPDs expressed the view that EPAs are not a comprehensive assessment tool and, therefore, were less likely to use them. Even among those FPDs who recognized the value of EPAs, the concern about workload for themselves and faculty dominated.

FPDs described lack of incentives, a lack of buy-in for change, and a need for training as other barriers to implementation. The time and effort involved with implementation could seem overwhelming as this involves software changes, tool development, as well as training and education for administrators, faculty, and fellows. This was particularly important given the apparent limited knowledge dissemination as described in the theme below. Since FPDs have many other requirements involved in running a program, their priorities could be shifted away from implementing new practices. Furthermore, FPDs who were new to their role and had less experience expressed less ability to innovate as they acclimated to their role and focused on fellowship recruitment, mentorship, and educational needs.

Knowledge dissemination surrounding EPAs: Training resources are needed to better understand the EPA framework and rating scales

Overall, FPDs described a general lack of knowledge and training resources on EPAs. For those familiar with EPAs, the most common sources of information were national meetings, particularly within their own subspecialties. Several also described personal involvement in the development of the EPAs. Institutional training on EPAs was uncommon. Many FPDs expressed a limited understanding of how the EPA framework can be applied and a desire for information from a trusted centralized source.

Few participants described efforts to learn more about EPAs through self-directed learning. They reported perceptions of the EPAs as an unfinished product, still being developed and evolving as a concept. FPDs expressed a desire for clarity about how to use the EPAs overall and how to use the rating scale, with some FPDs advocating for the development of a better assessment tool. Many FPDs in the nonuser group did not realize there was a published rating scale with a validity evidence to assess trainees on their performance of EPAs. FPDs also commented that the value of EPA assessment is unclear when compared to milestone-based assessment.

Limited use of EPAs: Data requests from governing bodies will prompt FPDs to use EPAs beyond research participation

The current use of EPAs was often limited to fellow assessment, and frequently in the context of research studies. Additional applications of the EPA framework reported were curriculum development, individual assessment, stimulating discussion for learning plans and remediation. Several reasons influenced the FPDs use or nonuse of the EPAs. Among EPA users, personal incentives to participate in research, a sense of good citizenship, advancement of educational methodology, or the influence of an EPA champion within their subspecialty were mentioned. Nonusers of EPAs were more likely to believe EPA assessment involved unnecessary work with little additional value. It was unclear to FPDs how additional assessment data would be used by governing bodies and future employers, impacting the perceived value of EPAs and the incentive to implement a new process to assess fellows. Indeed, many FPDs commented on the need for these data to be required or requested by an external organization (eg, ABP, ACGME) prior to initiating EPA assessments.

Comparison of EPAs to milestones: Desire for a tool that combines the best aspects of both assessment methods

The respondents discussed various strengths and weaknesses of both the EPAs and the milestones. Commonly mentioned differences between the 2 included the complexity of language and concepts, the scope of content within each component, and the user-friendliness of the assessment tools. Most EPA users appreciated the clear and simple language of EPAs and the level of supervision scale commonly used with EPA assessments compared with milestones. Additionally, the intuitive nature of entrustment and real-world applicability of EPAs made this tool seem more meaningful and often preferred to milestones.

However, some FPDs expressed concern that EPAs were less specific than milestones and often too broad for meaningful feedback. In this way, they described the potential complementary broad nature of EPAs with the more granular milestones for informing assessment and learning plans. FPDs also described how the extremes of the scale may not be applicable to all EPAs. For example, they questioned level one (Observe only) for certain EPAs such as Handovers, and level 5 (Trusted to lead at regional or national levels) for EPAs like Engage in Scholarly Activities and Lead within the Subspecialty Profession, as these are felt to be aspirational for faculty. Participants also discussed the role of governing bodies as they compared the use of EPAs and milestones. While both tools are aligned and connected to one another by way of the ACGME competencies, the requirements set forth by the ACGME are a primary driver of milestone use, making this the default assessment. FPDs expressed a desire for a single approach to assessment either by replacing milestones with EPAs or better integrating the 2 together.

Importantly, FPDs highlighted that the usefulness of any framework relied upon the ability to provide meaningful assessments, identify deficiencies, create action plans, and discriminate between individuals and assessment levels. These included assessments related to readiness for graduation from fellowship. They also discussed the value of narrative feedback as opposed to objective assessment ratings.

Discussion

Our study represents the first characterization of pediatric subspecialty FPDs’ experiences with and perspectives of EPAs. The implementation process for any new tool is complex, often requires significant time and resources, and has varying degrees of success. We used the CFIR framework to explore the different constructs involved in the implementation of the EPAs, which include domains such as the outer and inner settings, individuals, intervention, implementation, and process. Participating FPDs described several facilitators and barriers to using EPAs including a general lack of knowledge regarding their purpose, available rating scales, and integration with the milestones. Even though EPAs were created for pediatric subspecialties almost a decade ago, few FPDs use them outside of assessment and research.

A majority of participants described the role of regulatory requirements (Outer Setting) to adopt the EPAs consistently within their program, using the ACGME mandate for milestone reporting as an example. Since the completion of our study, the ABP announced a plan to require EPA assessments in the certification process for pediatric subspecialties beginning in 2028. Therefore, all pediatric fellowship programs will be required to use EPAs in this capacity within the next few years. However, the goal is not to simply create another task for program directors but rather to maintain a standard for the public and provide a better framework for ensuring pediatric subspecialty fellows graduate with the ability to perform the essential activities needed by their patients without supervision.

For more effective implementation, our results suggest the need for a broader multi-faceted approach to educating FPDs (Individuals) about the EPAs and ways to use them meaningfully. Depending upon the individual FPD's background and interests, the understanding of CBME and how the EPAs fit into the overall application of CBME may be limited. Outreach through multiple forums, as described by study participants, is likely necessary. The desire for standardized materials for training and implementation was stated as useful for ease of implementation. Having standardized resources may not only ease implementation but also help promote a shared mental model across the pediatric subspecialty educational community, a factor key to successful implementation. 35

Additionally, knowledge dissemination through existing communities of practice such as national or local educational meetings and the importance of “champions” who can support and educate less experienced FPDs (Inner Setting) were highlighted. Leveraging and reinforcing this concept of educational communities of practice may not only improve engagement in learning, particularly for the novice user, but also effectiveness of practice. 36 The positive influences of both communities of practice and champions have been demonstrated in other healthcare-related implementation efforts.37,38 Self-directed learning was less commonly reported, primarily among those who were more actively engaged in the development of EPAs. However, the role of self-directed learning may become more relevant now that the external forces for EPA implementation (ie, ABP requirement) are more prominent.

When implementing a new(er) framework such as EPAs (Intervention), there needs to be consideration of the complexity of the intervention and knowledge around the value gained. 26 FPDs familiar with EPAs describe the ease of understanding them when used for assessment because they describe real clinical tasks in their daily practice. This impression is consistent with other studies describing perceptions of EPAs by learners and faculty and the validity work on the level of supervision scales, where participants received no training prior to use.11,16,18 Furthermore, the concept of entrustment, while complex and nuanced in decision-making, can be intuitive for faculty and program directors. Thus, the scales anchored in levels of supervision translate more easily with an assessment of fellows. More importantly, entrustment can be seen as the pinnacle of training before launching into real-world practice after graduation. 39

While many FPDs recognize the value of the EPA concept for the reasons just described, they also expressed a desire for additional information about validity, application, and impact on outcomes. Although validity evidence has been generated for the assessment scales of the common pediatric subspecialty EPAs, there seemed to be a lack of awareness among FPDs, especially nonusers, which further supports the need for strong knowledge dissemination efforts. 16 Similar efforts for generating validity evidence for subspecialty-specific EPAs will also be important and are ongoing. Focusing on the subspecialty-specific EPAs, as those were identified as more meaningful, may be an effective approach during the initial stages of implementation. FPDs also raised questions about how the use of EPAs would impact progression through training, the range of the scale, determination for graduation readiness, and clinical performance postgraduation. Some work in these areas has been reported in other fields and other countries, including addressing the important issue of their use for high-stakes decision-making for graduation or certification.11,18 Recent studies also suggest FPDs may believe the level of supervision required at graduation may differ based on the specific EPA.17,40

Finally, given the current ACGME requirement for milestone reporting, FPDs queried the integration of an EPA framework into the existing system. Many recognized the complementary nature of milestones and EPAs, as previously described. 8 For example, the EPA framework for assessment may better identify a fellow's readiness to perform the essential activities of a subspecialty or their need for remediation, while the milestones provide an assessment of the specific competencies required for the execution of those activities. In this way, FPDs described using both tools to not only perform assessment but also inform individualized learning plans and curriculum development. As the ACGME, ABP, and pediatric education community work together to develop Milestones 2.0 for each subspecialty, this process presents an opportunity to educate FPDs about the connection between milestones and EPAs and continue to align the overall CBME assessment framework in pediatric subspecialties. Collaborative efforts between the ABP and APPD SPIN to directly connect subspecialty EPA supervision scale ratings to milestone subcompetencies have already begun, and similar efforts have been demonstrated in pediatric and medicine residency programs.41-43 Dissemination of these efforts in accessible and usable forms will be essential, particularly given the concern expressed by FPDs, including current EPA users, about additional workload, and integration into the current workflow. Access to common resources for training, assessment tools, and application using currently available electronic platforms can help support time-constrained FPDs during implementation.

Several limitations to our study should be acknowledged. We intentionally aimed for a diverse cohort of FPDs (experience, geography, and subspecialty) and to provide a balance of self-reported EPA users and nonusers. However, EPA use was often confined to assessment and research participation, thus, the identified factors influencing successful implementation for other applications may be different with greater understanding and use. The themes of limited knowledge and barriers will be important for education and dissemination efforts. A quantitative study of all FPDs was informed by our data and may capture additional information on our aims, as well as providing a framework for implementation. The research team comprised highly engaged educators, potentially providing a deeper/nuanced understanding of the participants’ words but the identified codes and themes may have been different with a group less involved in the broader educational community. Finally, our study was conducted prior to the ABP's notification regarding EPA assessments and certification, so we were unable to explore further FPDs reaction and anticipated needs with this change.

Conclusions

The key themes identified in this work contain important factors to inform the approach to effective and meaningful implementation: (1) supporting and educating FPDs about the EPAs and the level of supervision rating scales; (2) ongoing assessment of the value of EPAs in training and outcomes after graduation which may include patient care metrics, involvement in quality and safety programs, and leadership activities; and (3) practical integration with current systems and workflow such as dissemination of specialty-specific evaluation tools and the ability to use of EPA ratings to generate the required milestone report. Generating additional data and engaging full stakeholder input will be critical to avoid this approach being viewed as another regulatory requirement and accomplish meaningful and transformative implementation across the pediatric subspecialty community.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-mde-10.1177_23821205231225011 for Exploring Factors for Implementation of EPAs in Pediatric Subspecialty Fellowships: A Qualitative Study of Program Directors by Angela S. Czaja, Richard B. Mink, Bruce E. Herman, Pnina Weiss, David A. Turner, Megan L. Curran, Diane E. J. Stafford, Angela L. Myers and Melissa L. Langhan in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-mde-10.1177_23821205231225011 for Exploring Factors for Implementation of EPAs in Pediatric Subspecialty Fellowships: A Qualitative Study of Program Directors by Angela S. Czaja, Richard B. Mink, Bruce E. Herman, Pnina Weiss, David A. Turner, Megan L. Curran, Diane E. J. Stafford, Angela L. Myers and Melissa L. Langhan in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our study coordinator, Marzia Hazara, B.S., and our consultant, Dr Dorene Balmer, for their contributions to the study and the ABP Foundation for their financial support.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Angela S. Czaja, Richard B. Mink, Bruce E. Herman, PninaWeiss, David A. Turner, Megan L. Curran, Diane E. J. Stafford, Angela L. Myers, Melissa L. Langhan all participated in the analysis of data, drafting and critical review of the manuscript and final approval of the work product. Richard Mink and Melissa Langhan designed the study and obtained funding for the study.

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: David Turner is employed by the American Board of Pediatrics; the remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding: The authors received the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a grant from the American Board of Pediatrics Foundation. This manuscript does not represent the views of the ABP or the ABP Foundation.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: Theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638-645. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris P, Bhanji F, Topps M, et al. Evolving concepts of assessment in a competency-based world. Med Teach. 2017;39(6):603-608. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1315071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavares W, Rowland P, Dagnone D, McEwen LA, Billett S, Sibbald M. Translating outcome frameworks to assessment programmes: Implications for validity. Med Educ. 2020;54(10):932-942. doi: 10.1111/medu.14287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Melle E, Frank JR, Holmboe ES, Dagnone D, Stockley D, Sherbino J. A core components framework for evaluating implementation of competency-based medical education programs. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):1002-1009. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000002743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system–rationale and benefits. New Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051-1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rushton JL, Hicks PJ, Carraccio CL. The next phase of pediatric residency education: The partnership of the Milestones Project. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(2):91-92. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edgar L, McLean S, Hogan SO, Hamstra S, Holmboe ES. The Milestones Guidebook, 2020 version . Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education; 2020. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/milestonesguidebook.pdf

- 8.Carraccio C, Englander R, Gilhooly J, et al. Building a framework of entrustable professional activities, supported by competencies and milestones, to bridge the educational continuum. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):324-330. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carraccio C, Englander R, Holmboe ES, Kogan JR. Driving care quality: Aligning trainee assessment and supervision through practical application of entrustable professional activities, competencies, and milestones. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):199-203. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones MD, Jr, Rosenberg AA, Gilhooly JT, Carraccio CL. Perspective: Competencies, outcomes, and controversy–linking professional activities to competencies to improve resident education and practice. Acad Med. 2011;86(2):161-165. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820442e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, Jiang Z, Qi X, et al. An update on current EPAs in graduate medical education: A scoping review. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1981198. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2021.1981198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ. 2005;39(12):1176-1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langhan ML, Stafford DEJ, Myers AL, et al. Clinical competency committee perceptions of entrustable professional activities and their value in assessing fellows: A qualitative study of pediatric subspecialty program directors. Med Teach. 2023;45(6):650-657. doi: 10.1080/0142159x.2022.2147054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Entrustable professional activities for subspecialties. American Board of Pediatrics. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.abp.org/subspecialty-epas

- 15.American Board of Medical Specialties. Member Boards Collaborate to Explore CBME; 2022. Accessed January 6, 2023. https://www.abms.org/newsroom/abms-member-boards-collaborate-to-explore-cbme/

- 16.Mink RB, Schwartz A, Herman BE, et al. Validity of level of supervision scales for assessing pediatric fellows on the common pediatric subspecialty entrustable professional activities. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):283-291. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner DA, Schwartz A, Carraccio C, et al. Continued supervision for the common pediatric subspecialty entrustable professional activities may be needed following fellowship graduation. Acad Med. 2021;96(7S):S22-S28. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000004091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Dowd E, Lydon S, O'Connor P, Madden C, Byrne D. A systematic review of 7 years of research on entrustable professional activities in graduate medical education, 2011-2018. Med Educ. 2019;53(3):234-249. doi: 10.1111/medu.13792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shorey S, Lau TC, Lau ST, Ang E. Entrustable professional activities in health care education: A scoping review. Med Educ. 2019;53(8):766-777. doi: 10.1111/medu.13879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauer KE. Seeking trust in entrustment: Shifting from the planning of entrustable professional activities to implementation. Med Educ. 2019;53(8):752-754. doi: 10.1111/medu.13920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carney PA, Crites GE, Miller KH, et al. Building and executing a research agenda toward conducting implementation science in medical education. Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1):32405. doi: 10.3402/meo.v21.32405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price DW, Wagner DP, Krane NK, et al. What are the implications of implementation science for medical education? Med Educ Online. 2015;20(1):27003. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.27003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung WJ, Wagner N, Frank JR, et al. Implementation of competence committees during the transition to CBME in Canada: a national fidelity-focused evaluation. Med Teach. 2022;44(7):781-789. doi: 10.1080/0142159x.2022.2041191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ten Cate O, Balmer DF, Caretta-Weyer H, Hatala R, Hennus MP, West DC. Entrustable professional activities and entrustment decision making: A development and research agenda for the next decade. Acad Med. 2021;96(7S):S96-S104. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000004106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Graaf J, Bolk M, Dijkstra A, van der Horst M, Hoff RG, Ten Cate O. The implementation of entrustable professional activities in postgraduate medical education in The Netherlands: Rationale, process, and current status. Acad Med. 2021;96(7S):S29-S35. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000004110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carraccio C, Martini A, Van Melle E, Schumacher DJ. Identifying core components of EPA implementation: A path to knowing if a complex intervention is being implemented as intended. Acad Med. 2021;96(9):1332-1336. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000004075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide no. 131. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):846-854. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mink R, Schwartz A, Carraccio C, et al. Creating the subspecialty pediatrics investigator network. J Pediatr. 2018;192:3-4.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119(10):1442-1452. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.107.742775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson J. Using conceptual depth criteria: Addressing the challenge of reaching saturation in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2017;17(5):554-570. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higginbottom G, Lauridsen EI. The roots and development of constructivist grounded theory. Nurse Res. 2014;21(5):8-13. doi: 10.7748/nr.21.5.8.e1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545-547. doi: 10.1188/14.onf.545-547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holtrop JS, Scherer LD, Matlock DD, Glasgow RE, Green LA. The importance of mental models in implementation science. Front Public Health. 2021;9:680316. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.680316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: Implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Flanagan ME, Damschroder L, Schmid AA, Damush TM. Inside help: An integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:2050312118773261. doi: 10.1177/2050312118773261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barker M, Lecce J, Ivanova A, Zawertailo L, Dragonetti R, Selby P. Interprofessional communities of practice in continuing medical education for promoting and sustaining practice change: A prospective cohort study. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2018;38(2):86-93. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ten Cate O, Carraccio C, Damodaran A, et al. Entrustment decision making: Extending Miller's pyramid. Acad Med. 2021;96(2):199-204. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss P, Schwartz A, Carraccio C, Herman BE, Mink RB. Minimum supervision levels required by program directors for pediatric pulmonary fellow graduation. ATS Sch. 2021;2(3):360-369. doi: 10.34197/ats-scholar.2021-0013OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choe JH, Knight CL, Stiling R, Corning K, Lock K, Steinberg KP. Shortening the miles to the milestones: Connecting EPA-based evaluations to ACGME milestone reports for internal medicine residency programs. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):943-950. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larrabee JG, Agrawal D, Trimm F, Ottolini M. Entrustable professional activities: Correlation of entrustment assessments of pediatric residents with concurrent subcompetency milestones ratings. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(1):66-73. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00408.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pitts S, Schwartz A, Carraccio CL, et al. Fellow entrustment for the common pediatric subspecialty entrustable professional activities across subspecialties. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(6):881-886. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-mde-10.1177_23821205231225011 for Exploring Factors for Implementation of EPAs in Pediatric Subspecialty Fellowships: A Qualitative Study of Program Directors by Angela S. Czaja, Richard B. Mink, Bruce E. Herman, Pnina Weiss, David A. Turner, Megan L. Curran, Diane E. J. Stafford, Angela L. Myers and Melissa L. Langhan in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-mde-10.1177_23821205231225011 for Exploring Factors for Implementation of EPAs in Pediatric Subspecialty Fellowships: A Qualitative Study of Program Directors by Angela S. Czaja, Richard B. Mink, Bruce E. Herman, Pnina Weiss, David A. Turner, Megan L. Curran, Diane E. J. Stafford, Angela L. Myers and Melissa L. Langhan in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development