Abstract

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare (1%–5%), aggressive form of breast cancer, accounting for approximately 10% of breast cancer mortality. In the localized setting, standard of care is neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) ± anti-HER2 therapy, followed by surgery. Here we investigated associations between clinicopathologic variables, stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (sTIL), and pathologic complete response (pCR), and the prognostic value of pCR. We included 494 localized patients with IBC treated with NACT from October 1996 to October 2021 in eight European hospitals. Standard clinicopathologic variables were collected and central pathologic review was performed, including sTIL. Associations were assessed using Firth logistic regression models. Cox regressions were used to evaluate the role of pCR and residual cancer burden (RCB) on disease-free survival (DFS), distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS), and overall survival (OS). Distribution according to receptor status was as follows: 26.4% estrogen receptor negative (ER−)/HER2−; 22.0% ER−/HER2+; 37.4% ER+/HER2−, and 14.1% ER+/HER2+. Overall pCR rate was 26.3%, being highest in the HER2+ groups (45.9% for ER−/HER2+ and 42.9% for ER+/HER2+). sTILs were low (median: 5.3%), being highest in the ER−/HER2− group (median: 10%). High tumor grade, ER negativity, HER2 positivity, higher sTILs, and taxane-based NACT were significantly associated with pCR. pCR was associated with improved DFS, DRFS, and OS in multivariable analyses. RCB score in patients not achieving pCR was independently associated with survival. In conclusion, sTILs were low in IBC, but were predictive of pCR. Both pCR and RCB have an independent prognostic role in IBC treated with NACT.

Significance:

IBC is a rare, but very aggressive type of breast cancer. The prognostic role of pCR after systemic therapy and the predictive value of sTILs for pCR are well established in the general breast cancer population; however, only limited information is available in IBC. We assembled the largest retrospective IBC series so far and demonstrated that sTIL is predictive of pCR. We emphasize that reaching pCR remains of utmost importance in IBC.

Introduction

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare type of breast cancer, with a prevalence of 1%–5% (1) in Western countries and a relatively higher prevalence in the African American (1, 2) and North African population (7%–11.1%; refs. 3, 4). IBC accounts for 10% of all breast cancer mortality, with a median overall survival of 4.2 years (5). Up to 56% to 84% of the patients with IBC have axillary lymph node involvement (6–8) and up to 25% of the patients have metastatic disease at diagnosis (9), underpinning the aggressive behavior of IBC.

IBC is a clinical diagnosis, characterized by criteria described by Dawood and colleagues (10). However, the pathologic confirmation of invasive carcinoma remains essential (10). The term “inflammatory” in IBC might be misleading since there is no, or little inflammation involved on microscopic examination. It instead refers to the inflammatory clinical presentation of edema, redness, and enlargement of the breast, which is thought to be caused by obstruction of dermal lymphatic vessels of the breast by tumor emboli. Tumor emboli in skin biopsies are observed in up to 75% of cases but do not represent a mandatory diagnostic criterion for IBC (11, 12).

IBC is presented with a higher percentage of the more aggressive surrogate molecular subtypes in comparison with the non-IBC population. Within IBC, 24% are reported to be triple negative (11, 13) and 32% to 45% are HER2+ (11, 13–15) in contrast to 10% to 15% of triple-negative and 13% to 15% of HER2+ cases for the non-IBC population (16). The median age of diagnosis is generally lower for IBC in comparison with locally advanced non-IBC (57.3 years for IBC vs. 64.3 years for locally advanced non-IBC; refs. 13, 14).

Because of the aggressive behavior, the international expert panel on IBC recommends trimodal therapy consisting of anthracycline- and taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT), followed by mastectomy and radiotherapy, in the localized setting (10). Anti-HER2 therapy is given in case of HER2+ tumors (10). Postoperatively, adjuvant systemic therapy may be delivered according to the stage at diagnosis and degree of pathologic response, and endocrine therapy is administered when indicated. However, despite this multimodal treatment, and improvement of systemic treatments over time, survival rates are still generally lower as compared with stage-matched non-IBC tumors (8, 11, 17–19). Novel treatments are also being implemented for IBC; however, this has been extrapolated from studies investigating non-IBC, such as addition of pembrolizumab in neoadjuvant and metastatic setting for triple-negative IBC and the use of adjuvant T-DM1 for HER2+ IBC (20).

Response to NACT in breast cancer can be measured on the resection specimen by pathologic complete response (pCR), defined by the absence residual invasive carcinoma in the breast and lymph nodes (ypT0 or ypTis and ypN0 according to TNM classification (21). This is the most acknowledged one, following the international recommendations (22) and is independently associated with prognosis in the general breast cancer population (23, 24). In patients with IBC, studies indicate that pCR rates vary between 9% and 40% and depend on the (surrogate) molecular subtype (18, 19, 25–27). While pCR has been associated with an improved outcome for patients with IBC, survival rates are inferior to stage-matched patients with non-IBC (11, 18, 19, 26). Large retrospective studies have now established the value of stromal tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (sTIL) to predict pCR to NACT in all surrogate molecular subtypes of the general breast cancer population (28). Higher sTIL levels were, however, only associated with better prognosis in patients with triple-negative and HER2+ breast cancer. For IBC, this has only been sporadically investigated thus far, and often in relatively small cohorts (19, 26, 27).

A standardized method for evaluation of response to NACT was developed under the form of the residual cancer burden (RCB) score (29), which entails a continuous score as well as a categorical variable. An online tool calculates the score and class based on size of tumor bed, residual tumor size and cellularity, percentage of in situ carcinoma, number of positive lymph nodes and maximum diameter of the lymph node metastasis (30). Notably, the RCB is based on different measurements of residual disease as compared with standard staging by TNM. Both RCB-class and continuous RCB-scores have been associated with outcome with higher RCB-class and RCB-score resulting in worse outcomes for all patients as well as within the different molecular subtypes (24, 29). This has not been reported so far specifically in patients with IBC.

In this study, we assembled to our knowledge the largest multicentric retrospective cohort of patients with IBC with extensive clinical data collection, coupled with central pathologic review. We aimed at evaluating which variables, including sTILs, are associated with response to NACT, quantified by pCR and RCB, and determining the prognostic value of pCR in patients with IBC.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

This study included a retrospective, European multicentric cohort of female patients diagnosed with IBC and treated between October 1996 and October 2021 at eight different European hospitals (GZA hospitals Antwerp, Institut Jules Bordet Brussels, University Hospitals Leuven, Centre Henri Becquerel Rouen, Institut Curie Paris and Saint Cloud, Institut Paoli-Calmettes Marseille, IRCCS Policlinico San Martino Genova, Centre Hospitalier du Luxembourg). Patients were selected on the basis of the reported cT4d T-stage according to the TNM classification (21, 31). The clinical files were then refined for the clinical criteria defined by Dawood and colleagues, to discriminate between “real” IBC and secondary IBC, that is, IBC-like presentation due to progression of a neglected breast cancer and/or ulceration (10). Only patients who received NACT with or without anti-HER2 therapy, followed by surgery of the primary tumor, were eligible for this study. For the purpose of our research question, patients who only received neoadjuvant endocrine therapy were not included.

A data collection template was set-up centrally to collect clinicopathologic, treatment, and survival data, and was distributed to clinicians of the participating centers. Collected data were inspected for inconsistencies and potential input errors, which were rectified, before being consolidated into a central database. Lymph node status was recorded as the clinically assessed (cN) before neoadjuvant chemotherapy. BMI was stratified into underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), lean (18.5–25 kg/m2), overweight (25–30 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2) according to the WHO expert committee (32). Menopausal status was provided by the participating centers in accordance with the medical records. For the purpose of this study, patients were categorized in four subgroups by the status of estrogen receptor (ER) and HER2 (ER−/HER2−, ER−/HER2+, ER+/HER2−, and ER+/HER2+) determined by locally performed IHC ± in situ hybridization for the latter. ER was considered positive if Allred score was >1% and if H-score >0. In case no continuous score was provided, the historical status (positive vs. negative) was used if available. Analyses were stratified according to the subgroups.

Central Pathology Review

The archived diagnostic formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) biopsies were retrieved for central pathology review, including a total number of 302 breast tumor biopsies, 16 skin biopsies, and 46 biopsies of breast tumor with overlying skin (Supplementary Table S1). Most of them, 315 samples, were core needle biopsies, with availability of 50 larger incisional biopsies. The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides were reviewed and consensus scoring by G. Floris, P. Vermeulen, and M. De Schepper, as performed in a systematical manner according to the The Cancer Genome Atlas pathology data sheet” (TCGA) adapted to IBC by including scoring of the presence of tumor emboli (33, 34).

sTILs were scored according to the guidelines of the international TILs working group (35), and evaluated in three representative fields. The mean of these three fields was used as sTIL level at a sample level. In case multiple samples were available, the average sTIL of all fields across all available samples was used at a patient level. In subsequent analyses, sTILs were considered both as a continuous variable, and as a categorical variable of three categories – low (sTIL score ≤ 10%), intermediate (sTIL score > 10% and < 60%), and high (sTIL score ≥ 60%; ref. 28). sTILs were scored both on tumor samples of the breast as well as breast skin samples. sTIL scoring on the latter was performed only in the invasive carcinoma according to the guidelines, hereby excluding the stroma surrounding the tumor emboli (ref. 36; Supplementary Fig. S1).

Tumor emboli were examined surrounding the invasive carcinoma and at distance in the skin in case skin biopsies were present at time of diagnosis. Density of emboli was determined by counting the maximum number of identifiable emboli under the microscope with magnification of 200× and field diameter of 1.25 mm.

Response to neoadjuvant systemic therapy was measured using pCR (defined as ypT0/is ypN0) and residual cancer burden (RCB) class (0 = pCR; I; II and III) as well as the continuous score (29). As RCB scores were systematically assessed only for patients diagnosed and treated at the University Hospitals Leuven, all analyses involving RCB were done strictly in this sub-cohort (Supplementary Table S2). Because of a relatively limited number of patients, these analyses were not done in the breast cancer subtypes.

Other parameters that were analyzed were retraction clefts and stromal reaction. Retraction clefts were evaluated on routine H&E section as optical empty spaces between tumor cells and stroma. This was scored binary with a cutoff of 20% according to Acs and colleagues (37). Stromal reaction pattern was scored in accordance with the TCGA scoring sheet (34).

Statistical Analysis

For cases with multiple biopsies sites per patient (tumor biopsy and skin biopsy), the concordance of sTIL score and tumor emboli between the two was first inspected using the Bland–Altman and Lin's Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) methods.

Linear regression models were used to investigate the association between sTILs, as the continuous dependent variable, and each of the standard clinicopathologic features. Associations between pCR, as a binary dependent variable, and each of the clinicopathologic features, as well as sTILs, were assessed using Firth logistic regression models. With RCB class as dependent variable, association analyses were performed using multinomial logistic regression models with RCB-0 as baseline. Furthermore, the impact of clinicopathologic features on the extent of residual disease in patients who did not achieve pCR, that is, RCB nonzero score, was inspected by analyzing the association of continuous RCB score with these variables using linear regression models performed on the corresponding subset of patients.

The three endpoints considered in this study are disease-free survival (DFS), distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS), and overall survival (OS). DFS was defined as the duration from diagnosis to the first event of either locoregional, contralateral, or distant recurrence, or death from any cause; DRFS as the duration from diagnosis to the first event of distant recurrence; and OS as the duration from primary diagnosis to death from any cause. The reverse Kaplan–Meier (KM) method was used to estimate the median follow-up. KM curves were constructed to inspect the probabilities of DFS and OS in patients with and without pCR, or in patients of different RCB classes. Cox regression models were used to evaluate the effect of either pCR, RCB class, or RCB score on DFS and OS. DRFS was analyzed considering death without distant recurrence as the competing event. Crude cumulative incidence curves accounting for the competing risk were used to estimate the event rates of this endpoint according to pCR status and RCB class. Regression analyses of DRFS were performed using Fine–Gray regression models.

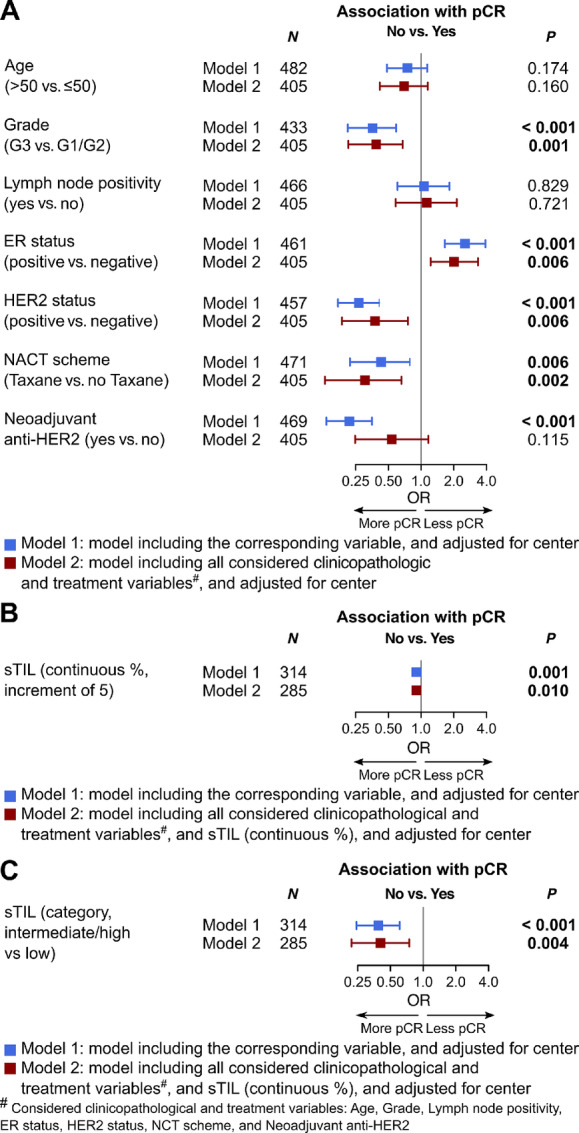

For each of the abovementioned regression analyses, two models were used. Model 1 assessed the association between the dependent variable and a single explanatory variable. Model 2 considered all clinicopathological variables of interest, and treatment where applicable, as independent variables. Both models accounted for the heterogeneity between centers by adjustment or stratification. In the text, Model 1 and Model 2 will be further referred to as univariable and multivariable models for simplicity.

Quantile regression was used to assess the potential non-linear associations between continuous dependent variables and categorical independent variables. In cases where the independent variable of interest was a continuous variable, a restricted cubic spline was used in the regression models to allow for nonlinear effects. A likelihood ratio (LR) test was then used for the comparative performance evaluation of the linear models and the models with nonlinear effects. Potential nonlinear associations suggested by these exploratory analyses are reported where appropriate.

Statistical analyses were executed using R version 4.1.1. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was used as the standard evidence criterion of statistical significance for all statistical tests. All P values reported were not corrected for multiple testing.

Ethics Statement

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the central ethics committee of University hospitals of Leuven (S62499) on December 20, 2019. No informed consent form (ICF) was requested as a waiver was granted given that many patients already passed away or progressed. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are not publicly available due to restrictions of the protocol approved by the ethics committees of the involved hospitals. Access to the data can be requested via the corresponding author.

Results

Presentation of the Study Cohort

A total of 494 patients with nonmetastatic IBC were included. The breast cancer subtype based on the ER status and HER2 status was available for 454 patients: 26.4% (120/454) were ER−/HER2−, 22.0% (100/454) ER−/HER2+, 37.4% (170/454) ER+/HER2−, and 14.1% (64/454) ER+/HER2+ (Table 1). Invasive breast cancer of no special type (IBC-NST, formerly called ductal breast cancer) was the dominant histologic type in the full study population (91.3%, 400/494) and in the respective subgroups (Table 1). In the entire cohort, most tumors were grade 3 (64.6%, 285/494), with relatively lower number of grade 3 tumors in the ER+/HER2− subgroup (46.5%, 73/157) as compared with the other subgroups (Table 1). Most patients had locoregional lymph node involvement at time of diagnosis (81.6%, 389/477 of all patients), without significant differences between the subgroups (Table 1). Of note, a center effect was observed with relatively lower number of patients having a clinical positive lymph node status at diagnosis in Institut Curie Paris (65%, 33/51) in comparison to GZA hospitals Antwerp (82%, 63/77). Most of the patients received taxane-based NACT (79.7%, 384/482), followed by mastectomy (96.8%, 367/379), and radiotherapy (96.7%, 412/426) with no differences in the treatment scheme between the different subgroups. Within the HER2+ groups, 35.9% (61/170) did not receive neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy (40%, 40/100 for ER−/HER2+; and 32.8%, 21/64 for ER+/HER2+ subgroups; Table 1). The majority of these patients (95.1%, 58/61) were diagnosed before 2010, when the neoadjuvant anti-HER2 treatment has become standard of care for these patients.

TABLE 1.

Baseline clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients in the entire cohort and in each of the breast cancer subgroups

| All N (%) | ER−/HER2−N (%) | ER−/HER2+N (%) | ER+/HER2−N (%) | ER+/HER2+N (%) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 494 (100) | 120 (26.4) | 100 (22.0) | 170 (37.4) | 64 (14.1) | ||

| Age | ≤50 | 194 (39.3) | 49 (40.8) | 32 (32.0) | 65 (38.2) | 30 (46.9) | 0.272 |

| >50 | 300 (60.7) | 71 (59.2) | 68 (68.0) | 105 (61.8) | 34 (53.1) | ||

| Menopausal status | Pre/Perimenopausal | 192 (41.8) | 49 (43.4) | 32 (34.0) | 67 (41.6) | 27 (44.3) | 0.512 |

| Postmenopausal | 267 (58.2) | 64 (56.6) | 62 (66.0) | 94 (58.4) | 34 (55.7) | ||

| Unknown | 35 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 3 | ||

| BMI category | Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.372 |

| Lean (18.5–25 kg/m2) | 165 (35.4) | 37 (33.9) | 38 (40.0) | 57 (34.8) | 19 (30.2) | ||

| Overweight (25–30 kg/m2) | 159 (34.1) | 39 (35.8) | 35 (36.8) | 52 (31.7) | 20 (31.7) | ||

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 139 (29.8) | 33 (30.3) | 20 (21.1) | 54 (32.9) | 24 (38.1) | ||

| Unknown | 28 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Focality | Unifocal | 230 (79.6) | 50 (82.0) | 48 (78.7) | 78 (79.6) | 34 (75.6) | 0.893 |

| Multifocal | 59 (20.4) | 11 (18.0) | 13 (21.3) | 20 (20.4) | 11 (24.4) | ||

| Unknown | 205 | 59 | 39 | 72 | 19 | ||

| Histology | ILC | 30 (6.9) | 6 (5.9) | 2 (2.3) | 14 (9.5) | 5 (7.9) | 0.301 |

| NST | 400 (91.3) | 95 (93.1) | 84 (96.6) | 129 (87.2) | 57 (90.5) | ||

| Other | 8 (1.8) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (3.4) | 1 (1.6) | ||

| Unknown | 56 | 18 | 13 | 22 | 1 | ||

| Grade | G1 | 15 (3.4) | 3 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (5.7) | 2 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| G2 | 141 (32.0) | 13 (12.3) | 23 (24.7) | 75 (47.8) | 22 (36.1) | ||

| G3 | 285 (64.6) | 90 (84.9) | 70 (75.3) | 73 (46.5) | 37 (60.7) | ||

| Unknown | 53 | 14 | 7 | 13 | 3 | ||

| ER status | Negative | 229 (48.5) | 120 (100.0) | 100 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Positive | 243 (51.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 170 (100.0) | 64 (100.0) | ||

| Unknown | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| HER2 status | Negative | 297 (63.6) | 120 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 170 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Positive | 170 (36.4) | 0 (0.0) | 100 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 64 (100.0) | ||

| Unknown | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| PR status | Negative | 295 (64.6) | 114 (97.4) | 93 (95.9) | 51 (31.9) | 22 (35.5) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 162 (35.5) | 3 (2.6) | 4 (4.1) | 109 (68.1) | 40 (64.5) | ||

| Unknown | 37 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 2 | ||

| Lymph node positivity | No | 88 (18.5) | 22 (18.6) | 13 (13.5) | 35 (20.7) | 11 (17.2) | 0.544 |

| Yes | 389 (81.6) | 96 (81.4) | 83 (86.5) | 134 (79.3) | 53 (82.8) | ||

| Unknown | 17 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Neoadjuvant anti-HER2 | No | 368 (76.7) | 115 (99.1) | 40 (40.0) | 161 (98.2) | 21 (32.8) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 112 (23.3) | 1 (0.9) | 60 (60.0) | 3 (1.8) | 43 (67.2) | ||

| Unknown | 14 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy scheme | Taxane | 384 (79.7) | 89 (76.7) | 82 (82.0) | 139 (83.7) | 53 (82.8) | 0.527 |

| No Taxane | 98 (20.3) | 27 (23.3) | 18 (18.0) | 27 (16.3) | 11 (17.2) | ||

| Unknown | 12 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Surgery | Mastectomy | 367 (96.8) | 81 (94.2) | 79 (100.0) | 122 (96.1) | 52 (100.0) | 0.067 |

| Tumorectomy | 12 (3.2) | 5 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Unknown | 115 | 34 | 21 | 43 | 12 | ||

| Radiotherapy | No | 14 (3.3) | 4 (4.2) | 2 (2.3) | 7 (4.8) | 1 (1.6) | 0.6752 |

| Yes | 412 (96.7) | 91 (95.8) | 85 (97.7) | 139 (95.2) | 62 (98.4) | ||

| Unknown | 68 | 25 | 13 | 24 | 1 | ||

| pCR | No pCR | 355 (73.7) | 81 (70.4) | 53 (54.1) | 152 (89.9) | 36 (57.1) | <0.001 |

| pCR | 127 (26.4) | 34 (29.6) | 45 (45.9) | 17 (10.1) | 27 (42.9) | ||

| Unknown | 12 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| RCB class# | 0 | 40 (28.2) | 8 (57.1) | 18 (42.8) | 2 (4.2) | 11 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| I | 12 (8.4) | 1 (7.1) | 5 (11.9) | 2 (4.2) | 4 (17.4) | ||

| II | 45 (31.7) | 2 (14.3) | 14 (33.3) | 19 (39.6) | 6 (26.1) | ||

| III | 45 (31.7) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (11.9) | 25 (52.1) | 2 (8.7) | ||

| Unknown | 21 | 14 | 0 | 7 | 0 | ||

#Statistics are described for patients diagnosed and treated at the University Hospitals Leuven.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics Based on Central Pathology Review

Central pathology review was performed on 366 unique samples accounting for 68.4% (338/494) of the cases with clinical information (Supplementary Table S1). Reasons for absent central review were missing samples from the historical archives or insufficient sample quality (Supplementary Fig. S2). Insufficient sample quality was characterized by faded H&E staining precluding morphologic interpretation. Clinicopathologic variables did not differ between the group of patients with evaluable biopsy and the group without (Supplementary Table S1).

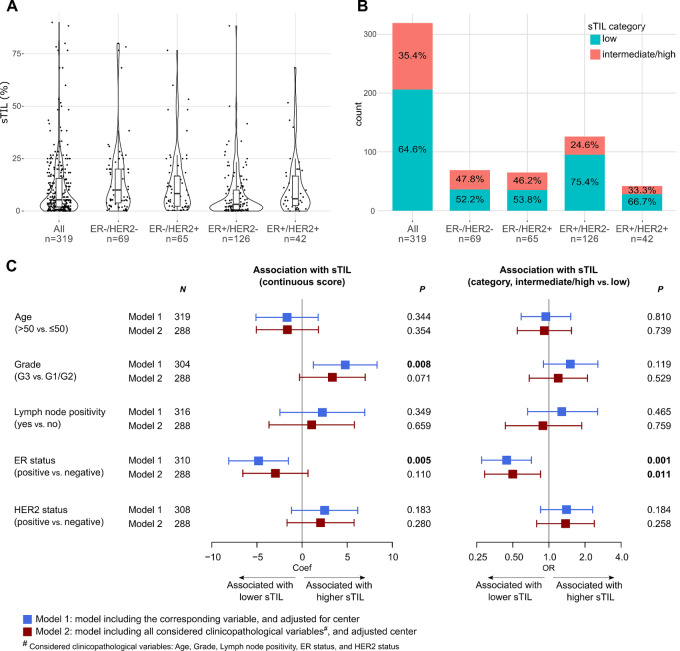

sTILs were scored for 94.4% (319/338) patients, among whom matched tumor and skin biopsies were available for 8 patients. Concordance analysis of these samples indicated a strong concordance in sTIL scoring between both biopsy sites for all patients (Supplementary Fig. S3). The average sTIL score of all samples from the same patient was therefore used at the patient's level in the subsequent analyses. Median sTILs was 5.3% [IQR (2.0%–15.6%)] and most patients (64.6%, 206/319) had low sTILs, defined as ≤10% (Fig. 1A and B). ER− tumors tended to have a higher sTIL level compared with ER+ tumors [median of 10.0%, IQR (3.9–20.0) in ER−/HER2−; and 8.3%, IQR (2.3–16.7) in ER−/HER2+; versus 3.2%, IQR (0.7–10.0) in ER+/HER2−; and 5.8%, IQR (2.6–16.7) in ER+/HER2+; Fig. 1A and B]. Given few cases with sTILs belonging to the “high” (≥60%) category (8 cases in the entire cohort, 4 in ER−/HER2−, and 1 in each of the remaining subgroups), we considered two categories of sTIL, “low” and “intermediate/high”, in subsequent analyses.

FIGURE 1.

sTIL scoring and its association with clinicopathological features in all patients. A, Distribution of sTIL (continuous) in the entire cohort and in subtypes. B, Distribution of sTIL (category) in the entire cohort and in subtypes. C, Forest plots showing the association of sTIL (continuous) and sTIL (categorical) with standard clinicopathologic variables evaluated by regression analyses in all patients.

Tumor emboli from peritumoral samples were identified for 19.8% (67/338) patients (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Among patients for whom skin biopsies were available, emboli were present in 49.2% (30/61) patients. In contrast to sTILs, there was a discordance between the levels of tumor emboli detected in tumor and skin biopsies, which however presented no clear orientation of favoring a biopsy site (Supplementary Fig. S4B and S4C). The tumor emboli were therefore separately described for tumor and skin biopsies (Supplementary Fig. S4D).

Association of sTILs with Clinicopathologic Features

Univariable regression analyses showed that higher sTILs was associated with high-grade and ER− tumors. This corresponds to the observed differences in sTIL level between subtypes. Only a trend was retained in the multivariable model (Fig. 1C). Quantile regressions revealed potentially nonlinear associations of several clinicopathologic variables with sTILs along its range, especially for grade, ER status, and HER2 status (Supplementary Fig. S5). However, no opposite associations to those detected by the linear analysis were observed.

Descriptive data suggested that sTILs tended to be lower in ILC tumors compared with subgroup-matched NST tumors although with a lack of statistical evidence due to very few cases of ILC (Supplementary Table S3). Missing data and unfeasibility to confirm histologic diagnosis with central pathology also hindered the evaluation with regard to this feature, therefore histologic subtype was excluded in our current multivariable analyses. Subgroup analyses did not provide evidence of an association between sTILs and clinicopathologic variables of interest in the two ER+ subgroups (Supplementary Fig. S6). In the ER− subgroups, opposite patterns according to HER2 status in terms of relationship with sTILs were observed for lymph node (LN) status. sTILs tended to be higher in LN-positive compared with LN-negative ER−/HER2− patients, while it was significantly higher in LN-negative compared with LN-positive ER−/HER2+ patients (Supplementary Fig. S6). Similarly, opposite trends were seen for the association of the continuous sTIL score and age, yet this was not reflected in the analyses considering sTIL as categorical variable. Nonlinear relationship was not assessed due to a limited number of cases in each of these subgroups.

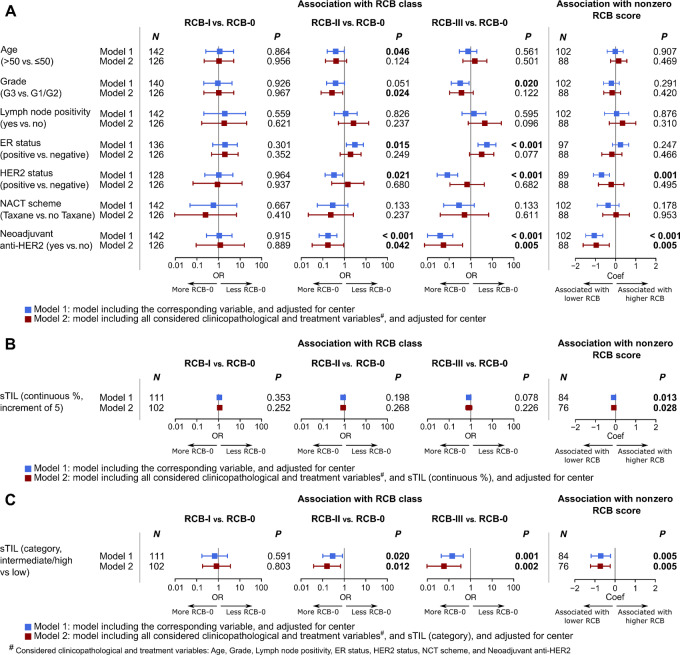

Response to NACT and its Association with Clinicopathologic Features

pCR was reached in 26.3% (127/482) patients, with the highest rates observed in the HER2+ groups (45.9%, 45/98 for ER−/HER2+; and 42.9%, 27/63 for ER+/HER2+), followed by 29.6% (34/115) in the ER−/HER2− group, and 10.1% (17/169) in the ER+/HER2− group (Table 1). A higher grade, ER− status, HER2+ status, taxane-based NACT, and anti-HER2 therapy were associated with pCR considering all patients (Fig. 2A). In subgroup analyses, these associations were recapitulated, but only for certain subgroups. Specifically, grade and NACT scheme were associated with pCR in the HER2+ subgroups (Supplementary Fig. S7A). Within the HER2+ subgroups, pCR rates were numerically higher in patients receiving neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy versus no neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy [52.4% (54/103) vs. 30.2% (19/63)], and similarly when stratifying according to ER status: 57.9% (33/57) versus 29.3% (12/41) in the ER−/HER2+ subgroup and 48.8% (20/41) versus 31.8% (7/22) in the ER+/HER2+ subgroup. All patients receiving anti-HER2 therapy also received taxane containing NACT. For patients with HER2+ disease not receiving anti-HER2 therapy, benefit of taxanes was clearly seen with pCR rate of 50% (16/32) in the taxane group and 20.7% (6/29) in the group without taxanes. Patients of age 50 years and below in the ER−/HER2+ and ER+/HER2− subgroups were more likely to achieve pCR, while in the ER−/HER2− subgroup, a trend toward the opposite direction was seen (Supplementary Fig. S7A). Higher sTILs were independently associated with pCR in the whole cohort (Fig. 2B and C). However, when subtype was taken into consideration, increase in sTILs (when considered as categorical variable) resulted in an increased odds of achieving pCR in the two ER− subgroups, albeit with weak statistical evidence (Supplementary Fig. S7B and S7C). We also explored several other pathologic features of IBC tumors such as tumor emboli, for their associations with pCR but did not observe any notable patterns (Supplementary Fig. S8).

FIGURE 2.

Association of pCR with clinicopathologic features and treatment in all patients. A–C, Forest plots showing the association of pCR with standard clinicopathologic and treatment variables (A), with sTILs (continuous %; B), and with sTILs (categorical; C) evaluated by regression analyses in all patients.

RCB scores were available for 142 patients (Leuven cohort, Supplementary Table S2). This subcohort did not differ significantly in clinicopathologic variables from the entire cohort, except for taxane-based NACT, which was higher in the Leuven cohort than in the total cohort [89.6% (146/163) vs. 79.7% (384/482)] and tumor focality, with relative higher unifocal tumors in the Leuven subcohort [87.7% (143/163) vs. 79.6% (230/289) respectively]. In this subcohort, patients in the ER−/HER2− subgroup achieved the highest rate of RCB-0 (pCR, P < 0.001; Table 1). On the contrary, the ER+/HER2− subgroup had both the lowest rate of RCB-0 and highest rate of RCB-III. No differences in clinicopathologic characteristics between RCB-I and RCB-0 (pCR) patients were observed (Fig. 3A, first column). The differences in baseline characteristics and treatment of patients with extensive residual disease, that is, RCB-II and RCB-III, and patients achieving RCB-0 (pCR) were similar to those found by the analyses regarding no-PCR versus pCR respectively (Fig. 3A, second and third columns). Considering only cases with residual disease, that is, nonzero RCB score, only the use of neoadjuvant anti-HER2 treatment was independently associated with a lower RCB extent of the residual disease (Fig. 3A, fourth column). Similar to pCR, higher sTILs seemed to be predictive of a lower RCB; however, the differences were more evident when comparing intermediate/high sTIL versus low sTIL (Fig. 3B and C). It was suggested by exploratory analyses that the association between RCB score and sTILs in patients with residual disease, that is, nonzero RCB score, could potentially be nonlinear (Supplementary Fig. S9), which needs further investigation in larger data series. In our current data, their correlation however remained positive throughout the range of sTILs as reflected by positive coefficient estimates.

FIGURE 3.

Association of RCB with clinicopathologic features and treatment in all patients. A–C, Forest plots showing the association of RCB, either as RCB class or continuous RCB score, with standard clinicopathologic and treatment variables (A), with sTILs (continuous %; B), and with sTILs (categorical; C) evaluated by regression analyses in all patients. Analyses were performed on the subset of patients diagnosed and treated at UZ Leuven, Belgium.

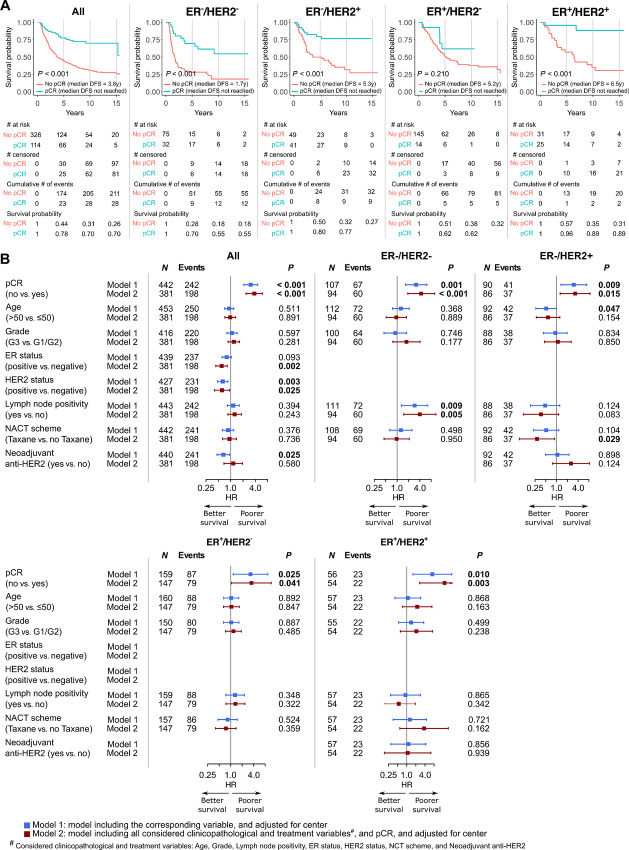

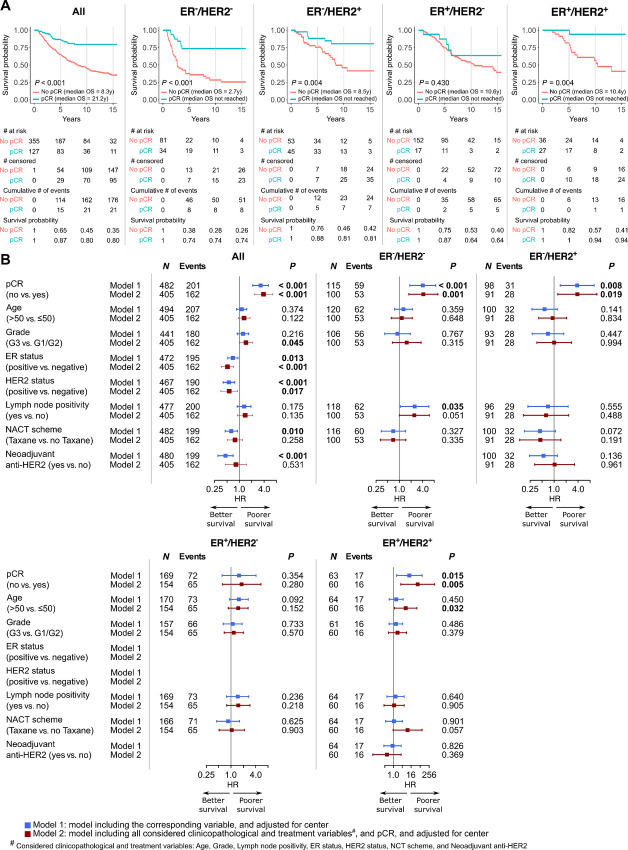

Association of Response to NACT with Prognosis

The median follow-up duration, median DFS, and median OS of all patients were 9.4, 5.8, and 11.6 years, respectively. Both univariable and multivariable analyses revealed that achieving pCR was generally associated with better DFS, DRFS, and OS in all patients, without and with consideration of subtype (Figs. 4 and 5; Supplementary Fig. S10). The survival benefit of achieving pCR was less extensive for the ER+/HER2− subtype compared with other subtypes. RCB classes were also shown to be prognostic for all endpoints (Supplementary Fig. S11 and S12). Of note, improved OS in patients achieving RCB-0 compared with patients with extensive residual disease, that is, RCB-III, was apparent throughout the maximum follow-up duration, while patients with less extensive or minimal residual disease, that is, RCB-II and RCB-I, started to show a noticeably worse OS at approximately 5 years of follow-up (Supplementary Fig. S11D).

FIGURE 4.

Association of pCR with DFS. A, Kaplan–Meier curves of DFS according to pCR. B, Forest plots showing the association of pCR and standard clinicopathologic and treatment variables with DFS quantified by Cox regression.

FIGURE 5.

Association of pCR with OS. A, Kaplan–Meier curves of OS according to pCR. B, Forest plots showing the association of pCR and standard clinicopathologic and treatment variables with OS quantified by Cox regression.

The independent prognostic role of RCB score in patients not achieving pCR, that is, nonzero RCB score, was also shown with strong statistical evidence for DFS and DRFS (Supplementary Figs. S11C and S12C). Its association with OS was presented as a visible trend by regression analyses, with a lack of statistical evidence (Supplementary Fig. S11F). This might correspond to the crossing of OS probability curves of the nonzero RCB classes observed at a later follow-up (Supplementary Fig. S11D).

Association of sTILs with Prognosis

In univariable analysis without subtype stratification, we observed that a higher sTIL was associated with improved survival for all endpoints (Supplementary Figs. S13 and S14). Its role as an independent prognostic factor was not confirmed by multivariable analyses adjusting for other clinicopathologic and treatment variables, and pCR (Supplementary Figs. S13 and S14). Analyses according to receptor subgroups revealed a trend towards improved survival of patients with higher sTILs only in the ER−/HER2+ subgroup.

Discussion

IBC represents a clinical breast cancer presentation which unfortunately is still under-investigated. In this study, we described, to the best of our knowledge, the largest retrospective cohort of primary IBC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy so far. We provide detailed characterization of clinicopathologic variables and central pathology review in relation to pCR, RCB, and survival outcomes.

Central pathology review illustrated the presence of tumor emboli in the skin for the 49.2% (30/61) patients for which pre-NACT skin biopsy was available. This is relatively lower than was described in the study by Hirko and colleagues (38); however, sampling before NACT of skin, for patients with IBC without direct skin invasion, is not standard in clinical practice, and was also not performed for a large majority of the patients in this cohort. For the majority of the patients only CNB were available and for some larger incisional biopsies were evaluable, which also might influence the findings of tumor emboli. This confirms again that the presence of tumor emboli on histology is not a prerequisite for the diagnosis of IBC (10), but still remains a remarkable phenomenon in IBC, and can be an aid when taken together with clinical presentation. The biological relevance of these emboli has already been suggested and should be further investigated (39–41).

sTILs in IBC were generally lower in comparison with what has been described in literature for IBC (sTILs were <10% in 64.6% in our cohort versus 35.8% in the cohort of Van Berckelaer and colleagues (26) and sTIL were <15% in 48.3% in the cohort of Arias-Pulido and colleagues (19)). In comparison with the general breast cancer population, sTILs were generally lower in our IBC cohort with sTIL < 10% in 64.6% of the cases versus 44% in general breast cancer population, as well as in the respective receptor subgroups (sTIL < 10% for 75.4% of ER+/HER2−; for 58.9% of HER2+ and 52.2% for ER−/HER2− subgroup in our IBC cohort versus sTIL < 10% in 56% of Luminal breast cancer, 44% in HER2+ breast cancer, and 29% in TNBC for the general breast cancer population; ref. 28). Similar to the previous reported general breast cancer population, relatively higher sTILs were observed in the ER− groups in comparison with the ER+ groups (19, 26, 28).

In our series, the overall pCR rate was 26.3% and is well within the range reported for IBC in the literature (9%–40%; refs. 18, 19, 25–27, 42). This is also comparable to the pCR rate reported by Denkert and colleagues but slightly lower than the 32.5% reported by Yau and colleagues in a general breast cancer population (20, 24, 28). In our series, we have a relatively higher proportion of patients with HER2+ tumors not receiving neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy (35.9% in our series vs. 13% in study by Yau and colleagues; ref. 24), and a numerical increase of pCR rate was observed in the group receiving anti-HER2 treatment, hereby likely underestimating pCR rates in our study in this subgroup of patients. However, studies comparing IBC with stage-matched non-IBC have shown variable results with either a remarkable difference in pCR (IBC 9% vs. non-IBC 20%; ref. 19) or similar pCR rates (11). In the latter study, survival was still impaired for patients with IBC, despite pCR (11). In our study, the addition of taxanes to the NACT was independently associated with increased pCR for all patients. Considering subgroups, the addition of taxane was only associated with pCR in the HER2+ subgroups, and especially for HER2+ patients not receiving anti-HER2 therapy. Our results therefore may challenge the recommended use of taxane-based NACT irrespective of subgroup consideration (10, 26, 43).

Similar to non-IBC, higher pCR rates for HER2+ and ER− subgroups were observed, however, we observed an absolute lower pCR rate in the ER−/HER2− subgroup in contrast to non-IBC (24, 28). Neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy was associated with higher pCR rates in unadjusted analysis, but not after adjusting for other clinicopathologic variables. This might be due to the additional effect of NACT, given together with anti-HER2 therapy. Prospective trials with neoadjuvant anti-HER2 including patients with IBC have been performed demonstrating improved pCR rates with the addition of pertuzumab to NACT-trastuzumab (44, 45), and improved outcomes with continuation of anti-HER2 treatment in the adjuvant setting (46); however, there was no formal reporting on the results specifically for the IBC cohort.

pCR was independently associated with HER2+ and ER− status, as well as tumor grade 3, and receipt of taxane-based chemotherapy in the entire cohort. The association with HER2+ status is possibly mediated by the effect of anti-HER2 therapy. This was only given in 62.8% of patients with HER2+ IBC, although a numerically higher pCR rate in patients receiving neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy was observed. The effect of the clinicopathologic variables of interest beyond ER and HER2 varied across the different subgroups, supporting the fact that the biology and thus stratification according to receptor status remains important in IBC. Reaching pCR was independently associated with DFS and OS in the different subgroups except for OS in the ER+/HER2− group where only a trend could be observed. ER negativity and HER2 negativity were each associated with poorer DFS and OS in multivariable analyses. This is in line with previously reported impaired outcomes of ER− or HER2− IBC in comparison with ER+ and HER2+ IBC (11, 18, 26, 47), but conflicts with the results presented by Liu and colleagues In that study, the authors reported that pCR is not prognostic and that ER+ IBC was not associated with better outcomes (42).

RCB classification was available for a subset of patients, in which we were able to show the prognostic dimension of RCB class. These results are in line with the results from the analyses of pCR and what has been reported for classic forms of breast cancer in general (24, 29). In patients with residual disease, a lower RCB score was associated with better DFS and DRFS. An association of lower RCB score with better OS was observed in early setting of follow-up of these patients, which was however diminished at a later follow-up time, that is, 10 years. Nevertheless, this needs to be interpreted with caution given the low numbers in this cohort.

Our results show that high sTIL are predictive for reaching pCR in the entire cohort; however, within the different receptor subgroups, this association could not be seen. This is in contrast to what has been described for the general breast cancer population where sTILs were predictive for pCR for all patients and for all breast cancer receptor subgroups (28). The prognostic effect of sTIL on OS is reduced when considering pCR in our series, which is similar to what has been described in the general breast cancer population (28), a trend could be observed for improved DFS and OS with increasing sTIL, even in the ER+/HER2− subgroups.

It has been reported that the immune microenvironment is different in IBC from non-IBC, with relatively higher IHC expression of PD-L1 on the sTILs, especially on B lymphocytes, and that these differences may have a prognostic significance (19, 26, 48). Moreover, Bertucci and colleagues demonstrated higher expression of different immune checkpoint molecules in comparison to non-IBC such as TIM3, CD27, CD70, CTLA4, ICOS, IDO1, LAG3, PDCD1, TNFRSF9, PVRIG, CD274 (PD-L1), and TIGIT (49). These data suggest that a relatively higher proportion of patients with IBC might be suitable candidates for immune checkpoint therapy (ICT). Patients in our study did not receive ICT, and in the past patients with IBC were often excluded from clinical trials because of the aggressive behavior of their disease. The PELICAN phase II trial (PELICAN-IPC 2015–016/Oncodistinct-003; NCT03515798), investigating the addition of pembrolizumab to standard NACT regimen for patients with HER2− IBC, is trying to address this treatment inequality (50).

Our study presents three main limitations. First, given the selection criteria of this study, there might be a selection bias towards more aggressive subtypes of breast cancer because in the past and also still today, patients with ER+ IBC might have been more likely to be treated like ER+ non-IBC, not receiving NACT.

A second limitation of this study, and in general of retrospective studies on IBC, is its definition, which is currently based on a set of clinical symptoms. These are prone to subjective interpretation and are not always described in detail in the historical clinical files. Recent efforts by Jagsi and colleagues have elaborated the clinical criteria for IBC with a weighted scoring system and allows more standardization of the diagnosis (51). This will be validated prospectively and has the potential of homogenizing IBC diagnosis within and across hospitals.

No central pathology review was performed for ER and HER2 status, nevertheless the distribution of patients in the receptor subgroups in this study is similar to what has been reported before in IBC studies investigating pCR, demonstrating a relatively higher proportion of ER−/HER2− and HER2+ tumors (18, 19, 25–27, 42). Results reported in the different receptor subgroups need to be observed with caution as numbers and events per subgroup were sometimes low.

Finally, in this study, we have not collected data concerning race, given the retrospective nature of this study and the difficulties of categorizing races. It has, however, been reported that IBC is overrepresented in black women and that there is an impaired prognosis for black women with IBC in comparison with non-black woman (1). As this is a European cohort, one needs to be cautious comparing U.S. and European cohorts due to possible demographic differences and (access to) healthcare systems.

In conclusion, this is the largest retrospective study so far for IBC with central pathology review. We have demonstrated that sTIL was predictive of pCR, although this could not be confirmed in stratified analyses by subgroups, and that pCR was associated with better prognosis. The independent prognostic value of sTILs could however not be demonstrated in this series. We have further confirmed the importance of stratification according to ER and HER2 status in IBC. Efforts need to be made to improve pCR rates and survival rates, especially for patients with ER−/HER2− IBC.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1 shows clinicopathological characteristics of the entire cohort and the sub-cohort with central pathology performed.

Supplementary Table 2 shows clinicopathological characteristics of the entire cohort and the Leuven sub-cohort.

Supplementary Table 3 shows pCR rates and sTIL according to histology.

Supplementary Figure 1 shows examples of sTIL scoring in skin on H&E images.

Supplementary Figure 2 shows an overview of data flow in the study.

Supplementary Figure 3 shows concordance of sTIL scoring between tumor and skin biopsies.

Supplementary Figure 4 shows an overview of tumor emboli assessment.

Supplementary Figure 5 shows quantile regression analyses of sTIL with clinicopathological variables.

Supplementary Figure 6 shows subgroup analyses of the association of sTIL with clinicopathological variables.

Supplementary Figure 7 shows subgroup analyses of the association of pCR with clinicopathological and treatment variables.

Supplementary Figure 8 shows descriptive data of pCR rates according to several pathological features.

Supplementary Figure 9 shows potential non-linear association of RCB score with sTIL.

Supplementary Figure 10 shows analyses of the association of pCR with DRFS.

Supplementary Figure 11 shows analyses of the association of RCB with DRF and OS.

Supplementary Figure 12 shows analyses of the association of RCB with DRFS.

Supplementary Figure 13 shows analyses of the association of sTIL with DFS and OS.

Supplementary Figure 14 shows analyses of the association of sTIL with DRFS.

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support by the Fondation Cancer Luxembourg (FC/2018/07) and Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek – Vlaanderen (FWO, G059821N). G. Floris is recipient of a post-doctoral fellowship sponsored by the KOOR from University Hospitals Leuven, and M. De Schepper is funded by the fund Nadine de Beauffort, the FWO and the Fondation Cancer Luxembourg. H. Wildiers is a recipient of the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek – Vlaanderen (funds from The Research Foundation – Flanders).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Communications Online (https://aacrjournals.org/cancerrescommun/).

Authors’ Disclosures

F. Richard reports grants from FWO during the conduct of the study. F. Clatot reports personal fees and non-financial support from MSD, Merck Serono, Novartis, Gilead, Astra Zeneca, Lilly; and non-financial support from Pfizer outside the submitted work. C. Molinelli reports personal fees from Novartis, Lilly, and non-financial support from Gilead outside the submitted work. M. Lambertini reports grants and other from Gilead; other from Roche, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Seagen, MSD, Exact Sciences, Daiichi Sankyo, Ipsen, Takeda Libbs, Sandoz, and other from Knights outside the submitted work. G. Zoppoli reports other from Immunomica Ltd. outside the submitted work. K. Punie reports personal fees from Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Exact Sciences, Focus Patient, Medscape, MSD, Mundi Pharma, Need Inc, Novartis, Pfizer, Axiom, Hoffmann/La Roche, Sanofi, Seagen, and personal fees from Gilead outside the submitted work; in addition, K. Punie is an investigator and steering committee member in several oncology clinical trials [committee member of ESMO Young Oncologists Committee, vice-president of Belgian Society of Medical Oncology (BSMO), external advisory role for national reimbursement committee, commission of personalized medicine of Belgian government, EMA]. H. Wildiers reports other from Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Lilly, Pfizer, Novartis, Augustine Therapeutics, Astra Zeneca, and other from Roche outside the submitted work; and travel support from Gilead, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer. A. Vincent-Salomon reports grants and non-financial support from Ibex Medical Analytics; grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from Astra-Zeneca; personal fees and non-financial support from Daiichi-Sankyo; personal fees and non-financial support from Roche; grants and personal fees from MSD; grants from OWKIN, and grants and personal fees from PRIMAA outside the submitted work. G. Floris reports personal fees from Astra Zeneca outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Authors’ Contributions

M. De Schepper: Data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. H.-L. Nguyen: Data curation, software, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. F. Richard: Software, formal analysis, supervision, writing-review and editing. L. Rosias: Data curation, investigation, writing-review and editing. F. Lerebours: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. R. Vion: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. F. Clatot: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. A. Berghian: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. M. Maetens: Resources, funding acquisition, project administration, writing-review and editing. S. Leduc: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. E. Isnaldi: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. C. Molinelli: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. M. Lambertini: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. F. Grillo: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. G. Zoppoli: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. L. Dirix: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. K. Punie: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. H. Wildiers: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. A. Smeets: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. I. Nevelsteen: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. P. Neven: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. A. Vincent-Salomon: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. D. Larsimont: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. C. Duhem: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. P. Viens: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. F. Bertucci: Resources, investigation, writing-review and editing. E. Biganzoli: Software, formal analysis, supervision, methodology, writing-review and editing. P. Vermeulen: Conceptualization, resources, supervision, investigation, methodology, writing-review and editing. G. Floris: Conceptualization, resources, supervision, methodology, writing-review and editing. C. Desmedt: Conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, visualization, methodology, project administration, writing-review and editing.

References

- 1. Abraham HG, Xia Y, Mukherjee B, Merajver SD. Incidence and survival of inflammatory breast cancer between 1973 and 2015 in the SEER database. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021;185:229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hance KW, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, Young HA, Levine PH. Trends in inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program at the national cancer institute. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:966–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boussen H, Bouzaiene H, ben Hassouna J, Gamoudi A, Benna F, Rahal K. Inflammatory breast cancer in tunisia: reassessment of incidence and clinicopathological features. Semin Oncol 2008;35:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soliman AS, Banerjee M, Lo AC, Ismail K, Hablas A, Seifeldin IA, et al. High proportion of inflammatory breast cancer in the population-based cancer registry of gharbiah, Egypt Breast Journal 2009;15:432–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Viale G, Marra A, Curigliano G, Criscitiello C. Toward precision medicine in inflammatory breast cancer. Transl Cancer Res 2019;8:S469–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matro JM, Li T, Cristofanilli M, Hughes ME, Ottesen RA, Weeks JC, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer management in the national comprehensive cancer network: the disease, recurrence pattern, and outcome. Clin Breast Cancer 2015;15:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anderson WF, Schairer C, Chen BE, Hance KW, Levine PH. Epidemiology of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). Breast Dis 2005;22:9–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cristofanilli M, Valero V, Buzdar AU, Kau SW, Broglio KR, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) and patterns of recurrence. Cancer 2007;110:1436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wingo PA, Jamison PM, Young JL, Gargiullo P. Population-based statistics for women diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2004;15:321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dawood S, Merajver SD, Viens P, Vermeulen PB, Swain SM, Buchholz TA, et al. International expert panel on inflammatory breast cancer: consensus statement for standardized diagnosis and treatment. Ann Oncol 2011;22:515–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Monneur A, Goncalves A, Gilabert M, Finetti P, Tarpin C, Zemmour C, et al. Similar response profile to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, but different survival, in inflammatory versus locally advanced breast cancers. Oncotarget 2017;8:66019–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bonnier P, Charpin C, Lejeune C, Romain S, Tubiana N, Beedassy B, et al. Inflammatory carcinomas of the breast: a clinical, pathological, or a clinical and pathological definition? Int J Cancer 1995;62:382–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiao D, Zhang J, Zhu J, Guo X, Yang Y, Xiao H, et al. Comparison of survival in non-metastatic inflammatory and other T4 breast cancers: a SEER population-based analysis. BMC Cancer 2021;21:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zell JA, Tsang WY, Taylor TH, Mehta RS, Anton-Culver H. Prognostic impact of human epidermal growth factor-like receptor 2 and hormone receptor status in inflammatory breast cancer (IBC): analysis of 2,014 IBC patient cases from the california cancer registry. Breast Cancer Res 2009;11:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Costa SD, Loibl S, Kaufmann M, Zahm DM, Hilfrich J, Huober J, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy shows similar response in patients with inflammatory or locally advanced breast cancer when compared with operable breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the GeparTrio trial data. J Clin Oncol 2009;28:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harbeck N, Penault-Llorca F, Cortes J, Gnant M, Houssami N, Poortmans P, et al. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019;5:66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dawood S, Ueno NT, Valero V, Woodward WA, Buchholz TA, Hortobagyi GN, et al. Differences in survival among women with stage III inflammatory and noninflammatory locally advanced breast cancer appear early. Cancer 2011;117:1819–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Uden DJP, van Maaren MC, Bult P, Strobbe LJA, van der Hoeven JJM, Blanken-Peeters CFJM, et al. Pathologic complete response and overall survival in breast cancer subtypes in stage III inflammatory breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;176:217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arias-Pulido H, Cimino-Mathews AM, Chaher N, Qualls CR, Joste N, Colpaert C, et al. Differential effects of CD20+ B cells and PD-L1+ immune cells on pathologic complete response and outcome: comparison between inflammatory breast cancer and locally advanced breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021;190:477–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Newman AB, Lynce F. Tailoring treatment for patients with inflammatory breast cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2023;24:580–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. James DB, Mary KG, Christian W. TNM Classification of malignant tumours. 8th edition. Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Provenzano E, Vallier AL, Champ R, Walland K, Bowden S, Grier A, et al. A central review of histopathology reports after breast cancer neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the neo-tango trial. Br J Cancer 2013;108:866–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, Mehta K, Costantino JP, Wolmark N, et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet North Am Ed 2014;384:164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yau C, Osdoit M, van der Noordaa M, Shad S, Wei J, de Croze D, et al. Residual cancer burden after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and long-term survival outcomes in breast cancer: a multicentre pooled analysis of 5161 patients. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:149–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nakhlis F, Regan MM, Warren LE, Bellon JR, Hirshfield-Bartek J, Duggan MM, et al. The impact of residual disease after preoperative systemic therapy on clinical outcomes in patients with inflammatory breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2017;24:2563–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Berckelaer C, Rypens C, van Dam P, Pouillon L, Parizel M, Schats KA, et al. Infiltrating stromal immune cells in inflammatory breast cancer are associated with an improved outcome and increased PD-L1 expression. Breast Cancer Res 2019;21:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reddy SM, Reuben A, Barua S, Jiang H, Zhang S, Wang L, et al. Poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy correlates with mast cell infiltration in inflammatory breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2019;7:1025–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Denkert C, von Minckwitz G, Darb-Esfahani S, Lederer B, Heppner BI, Weber KE, et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, Rajan R, Kuerer H, Valero V, et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. MD Anderson Cancer Center. Available from: http://www3.mdanderson.org/app/medcalc/index.cfm?pagename=jsconvert3.

- 31. Edge SB. AJCC cancer staging manual. Springer. 2010;7:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO expert committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu J, Lichtenberg T, Hoadley KA, Poisson LM, Lazar AJ, Cherniack AD, et al. An integrated TCGA pan-cancer clinical data resource to drive high-quality survival outcome analytics. Cell 2018;173:400–416.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heng YJ, Lester SC, Tse GM, Factor RE, Allison KH, Collins LC, et al. The molecular basis of breast cancer pathological phenotypes. J Pathol 2017;241:375–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, Sirtaine N, Klauschen F, Pruneri G, et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs working group 2014. Ann Oncol 2015;26:259–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hendry S, Salgado R, Gevaert T, Russell PA, John T, Thapa B, et al. Assessing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in solid tumors: a practical review for pathologists and proposal for a standardized method from the international immunooncology biomarkers working group: part 1: assessing the host immune response, TILs in invasi. Adv Anat Pathol 2017;24:235–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Acs G, Khakpour N, Kiluk J, Lee MC, Laronga C. The presence of extensive retraction clefts in invasive breast carcinomas correlates with lymphatic invasion and nodal metastasis and predicts poor outcome: a prospective validation study of 2742 consecutive cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:325–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hirko KA, Regan MM, Remolano MC, Schlossman J, Harrison B, Yeh E, et al. Dermal lymphatic invasion, survival, and time to recurrence or progression in inflammatory breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2021;44:449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lehman HL, Dashner EJ, Lucey M, Vermeulen P, Dirix L, Van LS, et al. Modeling and characterization of inflammatory breast cancer emboli grown in vitro. Int J Cancer 2013;132:2283–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arora J, Sauer SJ, Tarpley M, Vermeulen P, Rypens C, Van Laere S, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer tumor emboli express high levels of anti-apoptotic proteins: use of a quantitative high content and high-throughput 3D IBC spheroid assay to identify targeting strategies. Oncotarget 2017;8:25848–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Robertson FM, Chu K, Boley KM, Ye Z, Liu H, Wright MC, et al. The class I HDAC inhibitor Romidepsin targets inflammatory breast cancer tumor emboli and synergizes with paclitaxel to inhibit metastasis. J Exp Ther Oncol 2013;10:219–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu J, Chen K, Jiang W, Mao K, Li S, Kim MJ, et al. Chemotherapy response and survival of inflammatory breast cancer by hormone receptor- and HER2-defined molecular subtypes approximation: an analysis from the National Cancer Database. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2017;143:161–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chainitikun S, Saleem S, Lim B, Valero V, Ueno NT. Update on systemic treatment for newly diagnosed inflammatory breast cancer. J Adv Res 2021;29:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, Roman L, Tseng LM, Liu MC, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bianchini G, Kiermaier A, Bianchi GV, Im YH, Pienkowski T, Liu MC, et al. Biomarker analysis of the NeoSphere study: pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel versus trastuzumab plus docetaxel, pertuzumab plus trastuzumab, or pertuzumab plus docetaxel for the neoadjuvant treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2017;19:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gianni L, Eiermann W, Semiglazov V, Manikhas A, Lluch A, Tjulandin S, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with trastuzumab followed by adjuvant trastuzumab versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone, in patients with HER2-positive locally advanced breast cancer (the NOAH trial): a randomised controlled superiority trial with a parallel HER2-negative cohort. Lancet 2010;375:377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rogé M, Salleron J, Kirova Y, Guigo M, Cailleteau A, Levy C, et al. Different prognostic values of tumour and nodal response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy depending on subtypes of inflammatory breast cancer, a 317 patient-study. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fernandez SV, MacFarlane AW 4th, Jillab M, Arisi MF, Yearley J, Annamalai L, et al. Immune phenotype of patients with stage IV metastatic inflammatory breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2020;22:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bertucci F, Boudin L, Finetti P, Van Berckelaer C, Van Dam P, Dirix L, et al. Immune landscape of inflammatory breast cancer suggests vulnerability to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncoimmunology 2021;10:1929724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bertucci A, Bertucci F, Zemmour C, Lerebours F, Pierga JY, Levy C, et al. PELICAN-IPC 2015–016/Oncodistinct-003: a prospective, multicenter, open-label, randomized, non-comparative, phase II study of pembrolizumab in combination with neo adjuvant EC-paclitaxel regimen in HER2-negative inflammatory breast cancer. Front Oncol 2020;10:575978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jagsi R, Mason G, Overmoyer BA, Woodward WA, Badve S, Schneider RJ, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer defined: proposed common diagnostic criteria to guide treatment and research. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2022;192:235–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1 shows clinicopathological characteristics of the entire cohort and the sub-cohort with central pathology performed.

Supplementary Table 2 shows clinicopathological characteristics of the entire cohort and the Leuven sub-cohort.

Supplementary Table 3 shows pCR rates and sTIL according to histology.

Supplementary Figure 1 shows examples of sTIL scoring in skin on H&E images.

Supplementary Figure 2 shows an overview of data flow in the study.

Supplementary Figure 3 shows concordance of sTIL scoring between tumor and skin biopsies.

Supplementary Figure 4 shows an overview of tumor emboli assessment.

Supplementary Figure 5 shows quantile regression analyses of sTIL with clinicopathological variables.

Supplementary Figure 6 shows subgroup analyses of the association of sTIL with clinicopathological variables.

Supplementary Figure 7 shows subgroup analyses of the association of pCR with clinicopathological and treatment variables.

Supplementary Figure 8 shows descriptive data of pCR rates according to several pathological features.

Supplementary Figure 9 shows potential non-linear association of RCB score with sTIL.

Supplementary Figure 10 shows analyses of the association of pCR with DRFS.

Supplementary Figure 11 shows analyses of the association of RCB with DRF and OS.

Supplementary Figure 12 shows analyses of the association of RCB with DRFS.

Supplementary Figure 13 shows analyses of the association of sTIL with DFS and OS.

Supplementary Figure 14 shows analyses of the association of sTIL with DRFS.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are not publicly available due to restrictions of the protocol approved by the ethics committees of the involved hospitals. Access to the data can be requested via the corresponding author.