Abstract

Uterine leiomyosarcoma is a high-grade sarcoma that might be associated with dismal outcome. There are no hematological markers that can be used to follow up the recurrence and/or progression of the tumor. We present a case of a 44-year-old female, who was diagnosed with uterine leiomyosarcoma. During her management course, serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) elevation was correlated with clinical and radiological disease progression on two separate occasions. This correlation should be further investigated to potentially integrate serum β-hCG as a predictive tool for clinical behavior and treatment response.

Keywords: Uterine leiomyosarcoma, Biomarker, β-hCG

Introduction

Uterine leiomyosarcoma accounts for 2-5% of uterine malignancies [1]. There are no hematological markers that can be used to follow up the recurrence and/or progression of the tumor. We present a case of a 44-year-old female, who was diagnosed with uterine leiomyosarcoma. During her management course, serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) elevation was correlated with clinical and radiological disease progression on two separate occasions.

Case Report

A 44-year-old female presented with prolonged heavy vaginal bleeding. She underwent dilation and curettage (D&C), which revealed malignant spindle cells with normal endometrial tissues, consistent with uterine leiomyosarcoma. Her initial ultrasound examination at our center showed a bulky uterus, with a mass at the posterior wall with cystic component, measuring 8 × 7 cm in size. Adnexa showed a normal appearance. Speculum examination showed normal vulvar, vaginal, and cervical anatomy.

Initial imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scan to the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed local disease without distant metastasis. Pelvic MRI showed a large uterine mass consistent with the known primary mass, measuring 10 × 7 × 9 cm. Serum β-hCG was ordered, and the level was within normal value (0.1 mIU/mL) prior to her mentioned radiological examinations.

According to the multidisciplinary clinic (MDC) panel decision, the patient underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy on May 30, 2019. Following surgery, the MDC panel decided to continue close follow-up without offering further treatment.

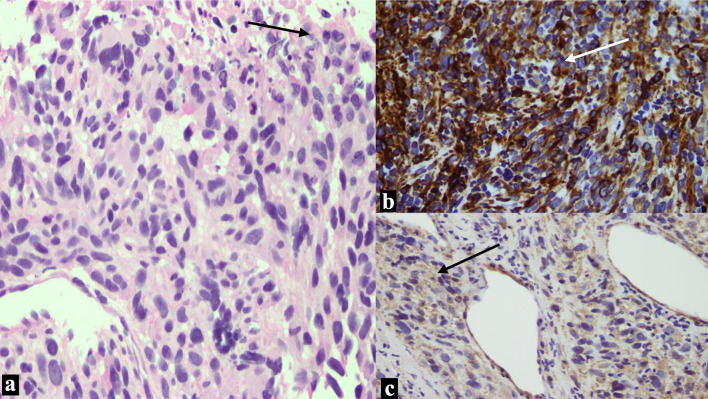

Pathological examination of the initial biopsy at the time of the D&C showed proliferation of spindle cells with severe nuclear pleomorphism and tumor necrosis. The mitotic rate was estimated at 35 mitotic figures/10 high-power field (HPF). The tumor cells were positive for desmin, smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon, while were negative for pan-cytokeratin CK-MNF. CD10 showed focal, weak staining as shown in Figure 1. Examination of the resection specimen revealed a 9.0 cm fleshy tumor, confined to the myometrium, with no evidence of infiltration to the adjacent tissue. Microscopy showed a high-grade leiomyosarcoma, with similar morphological features to the biopsy. The final pathological stage of the case was pT1bNx, FIGO IB.

Figure 1.

Images from the leiomyosarcoma. (a) There is proliferation of spindle cells with marked pleomorphism and necrosis at upper right corner (arrow). (b) The tumor cells are strongly diffusely positive for desmin (arrow). (c) Positive cytoplasmic staining for smooth muscle actin (arrow).

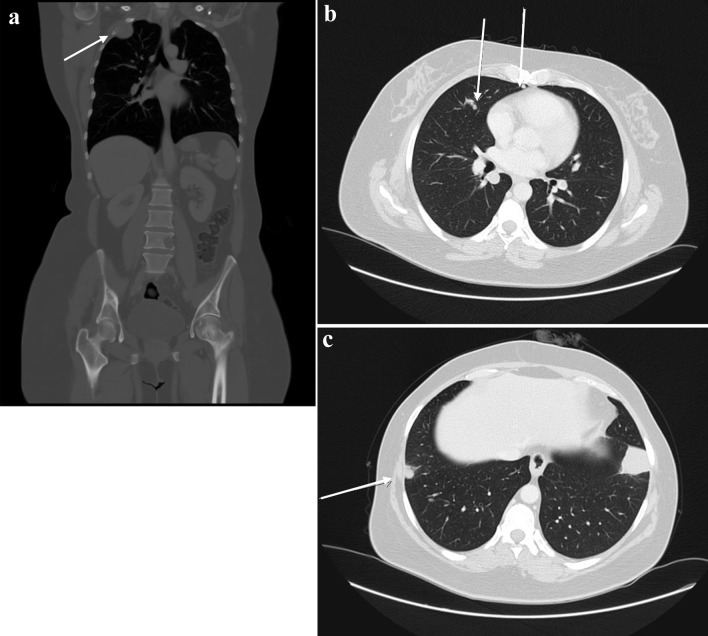

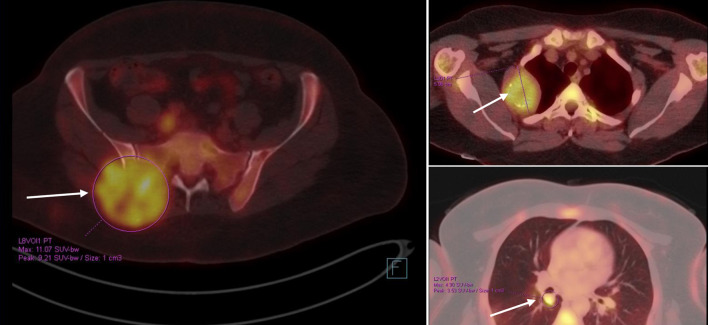

The patient was kept on regular follow-up with imaging and Pap smears, until August 2020, when she was discovered to have an enlarging pulmonary nodule in the right upper lobe, which on subsequent imaging showed interval enlargement, along with new multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules indicating pulmonary metastases (Fig. 2). Additionally, prominent right hilar lymph nodes were noted. Furthermore, a lytic bony lesion involving the second right rib, accompanied by an associated soft tissue component was consistent with a metastatic deposit. In addition, there was a small lytic lesion involving the left seventh rib. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan confirmed the widespread metastatic disease (Fig. 3). β-hCG level was repeated then and was still within normal levels (0.111 mIU/mL). A biopsy from the right sacral mass confirmed the presence of metastatic leiomyosarcoma.

Figure 2.

First disease progression shown on CT scan with contrast, manifested with multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules and two prominent right hilar lymph nodes, with multiple scattered destructive lytic bony lesions (arrows) (August 12, 2020) (a: coronal, bone window; b, c: axial, lung window). CT: computed tomography.

Figure 3.

PET/CT scan showing widespread metastatic disease (arrows) (September 10, 2020). Beta-hCG level was within normal levels. Beta-hCG: beta human chorionic gonadotropin; CT: computed tomography; PET: positron emission tomography.

The MDC panel decision was to proceed with palliative chemotherapy. On March 14, 2021, a CT scan showed disease progression in the lung and bony metastases, so she was switched to second line chemotherapy of doxorubicin, the first cycle of which was on April 26, 2021. A CT scan on June 24, 2021 revealed a larger soft tissue component in vertebral metastases, with further posterior wedging of L5 vertebral body with retro bulging compressing the thecal sac. Accordingly, she received 20 Gy/5 Fx, completed on July 12, 2021. The patient was switched to ifosfamide and received her first elective cycle on August 27, 2021, with mixed response.

On April 21, 2022, pelvic MRI showed marked progression of the metastatic deposit involving the left ischial tuberosity and acetabulum. The patient was started on pazopanib from the private sector in July 2022.

Imaging in December 2022 showed progression of the size of pulmonary metastasis, and new solitary subcapsular segment VI hepatic metastasis. The results were considered as oligo-progression, for which she received liver stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) at a dose of 45 Gy/5 Fx, finished on January 3, 2023.

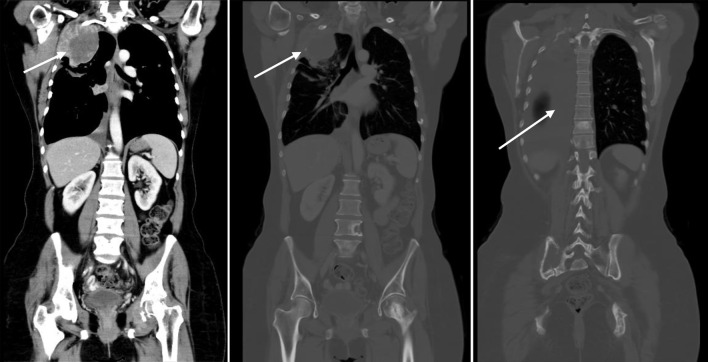

Imaging in February 2023 showed marked disease progression, manifested with enlarging extraosseous soft tissue component associated with destructive bony lesion involving the right second rib and left acetabulum, enlarging multifocal bilateral metastatic pulmonary lesions, and right-sided pleural effusion with pleural nodular thickening, suspicious for pleural carcinomatosis (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

CT scan showing disease progression (February 9, 2023): enlarging extraosseous soft tissue component associated with destructive bony lesion involving the right second rib and left acetabulum, enlarging bilateral pulmonary lesions, and moderate right-sided pleural effusion with new right pleural nodular thickening, suspicious for pleural carcinomatosis (arrows). Beta-hCG level was elevated (8.43 mIU/mL). Beta-hCG: beta human chorionic gonadotropin; CT: computed tomography.

β-hCG level was incidentally found to be mildly elevated on February 7, 2023 (8.43 mIU/mL). Repeating the test on March 12, 2023, the level remained elevated (8.44 mIU/mL). Brain MRI was done with no evidence of intracranial space occupying lesion or abnormal contrast enhancement.

Unfortunately, her disease continued to progress, and during 2023, she has undergone multiple palliative radiation treatments to various sites, and was admitted with acute hypoxic respiratory failure, pain crisis, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Discussion

Identifying tumor markers can be helpful in aiding in the diagnosis, stratification of patients and assessing treatment response. Other than in pregnancy, β-hCG has been described to be produced in gestational trophoblastic disease, and by other non-trophoblastic cancers, including, transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the bladder and urinary tract, rectal and gastrointestinal cancers, prostate cancer, lung cancer, neuroendocrine tumors and some breast and gynecological tumors [2-9].

Blood inflammatory markers were shown to be useful in differentiation between leiomyosarcoma and leiomyoma including high white blood cell (WBC) count, absolute neutrophil count (ANC), C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) levels [10].

In our case, a repeat test was performed to rule out the possibility of a false-positive result. Pregnancy was definitively excluded as the cause of elevated β-hCG levels since the patient had previously undergone hysterectomy and oophorectomy. A PET/CT scan helped in excluding any lesions indicative of an alternative primary cancer, and a brain MRI was performed to eliminate other potential secondary causes.

In the available literature, there are a few documented cases of β-hCG-producing sarcomas. β-hCG production was described in a small number of primary and recurrent osteosarcomas and osteogenic sarcomas [11-15], phyllodes tumors [16], dedifferentiated liposarcomas [17, 18] and synovial sarcomas [19]. In extra-uterine cases, elevated β-hCG was described in retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma [18, 20, 21], spermatic cord leiomyosarcoma [22, 23], and leiomyosarcoma of the small bowel [24]. To our knowledge, our case is the fourth in literature to describe a case of uterine leiomyosarcoma associated with elevated β-hCG [25-27]. What is special about this case was that the initial β-hCG levels were within normal levels, which then showed β-hCG elevation in association with the metastatic disease, flare up and resistance to chemotherapy, and palliative radiotherapy, suggesting that β-hCG can potentially play a prognostic role in such patients.

In uterine leiomyosarcoma, the initial rise in β-hCG levels might be associated with the tumor’s aggressive histology [25]. As our case developed β-hCG elevation with metastatic disease resistance to treatment, this can suggest that the metastatic clones flaring up the disease might have undergone a process of dedifferentiation and encompassing further genetic mutations associated with treatment resistance.

Limitations of our study include that β-hCG was not measured frequently during the course of the patient’s disease, as it has no routine proven clinical value or justification to be ordered. Also, thorough pathological studies were not done on the metastatic lesions of the patient, which cannot be compared with the primary tumor and prove for sure that dedifferentiation occurred. However, it is quite evident that the disease became more resistant to treatment, which alludes to the fact that the metastatic cells harbored different genetic make-up, as described in previous researches about discrepancy in mutations between primary tumor and metastatic lesions [28]. Also, β-hCG immunohistochemistry was not done on the primary disease specimens.

Conclusion

Tumor markers that are readily measurable in most institutions, like β-hCG, are needed in tumors like uterine leiomyosarcoma, a highly aggressive and often fatal cancer. In this report, we presented a rare case of a β-hCG-producing uterine leiomyosarcoma, wherein β-hCG levels showed the potential of serving as a prognostic factor and a marker for chemotherapy treatment resistance. However, further research is needed to gain a deeper understanding of this hypothesis and validate the potential of using β-hCG production as a marker of dedifferentiation and disease progression.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Funding Statement

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms.

Author Contributions

AZ and FA designed the overall concept and outline of the manuscript; AZ and FA contributed data collection; AZ, IM, MA, SS, AJ, RA and FA contributed to the writing, review of literature, editing the manuscript and final approval of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

- 1.George S, Serrano C, Hensley ML, Ray-Coquard I. Soft tissue and uterine leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(2):144–150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.9845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stenman UH, Alfthan H, Hotakainen K. Human chorionic gonadotropin in cancer. Clin Biochem. 2004;37(7):549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Span PN, Thomas CM, Heuvel JJ, Bosch RR, Schalken JA, vd Locht L, Mensink EJ. et al. Analysis of expression of chorionic gonadotrophin transcripts in prostate cancer by quantitative Taqman and a modified molecular beacon RT-PCR. J Endocrinol. 2002;172(3):489–495. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1720489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotakainen K, Ljungberg B, Haglund C, Nordling S, Paju A, Stenman UH. Expression of the free beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin in renal cell carcinoma: prognostic study on tissue and serum. Int J Cancer. 2003;104(5):631–635. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpelan-Holmstrom M, Louhimo J, Stenman UH, Alfthan H, Jarvinen H, Haglund C. Estimating the probability of cancer with several tumor markers in patients with colorectal disease. Oncology. 2004;66(4):296–302. doi: 10.1159/000078330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oberg K, Wide L. hCG and hCG subunits as tumour markers in patients with endocrine pancreatic tumours and carcinoids. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1981;98(2):256–260. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0980256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bepler G, Jaques G, Oie HK, Gazdar AF. Human chorionic gonadotropin and related glycoprotein hormones in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 1991;58(1-2):145–150. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(91)90037-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demirtas E, Krishnamurthy S, Tulandi T. Elevated serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin in nonpregnant conditions. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(10):675–679.quiz 691. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000281557.04956.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moutzouris G, Yannopoulos D, Barbatis C, Zaharof A, Theodorou C. Is beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin production by transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder a marker of aggressive disease and resistance to radiotherapy? Br J Urol. 1993;72(6):907–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suh DS, Song YJ, Roh HJ, Lee SH, Jeong DH, Lee TH, Choi KU. et al. Preoperative blood inflammatory markers for the differentiation of uterine leiomyosarcoma from leiomyoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:5001–5011. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S314219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalra JK, Mir R, Kahn LB, Wessely Z, Shah AB. Osteogenic sarcoma producing human chorionic gonadotrophin. Case report with immunohistochemical studies. Cancer. 1984;53(10):2125–2128. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840515)53:10<2125::aid-cncr2820531022>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee AF, Pawel BR, Sullivan LM. Significant immunohistochemical expression of human chorionic gonadotropin in high-grade osteosarcoma is rare, but may be associated with clinically elevated serum levels. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2014;17(4):278–285. doi: 10.2350/14-02-1436-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boss DS, Glen H, Beijnen JH, de Jong D, Wanders J, Evans TR, Schellens JH. Serum beta-HCG and CA-125 as tumor markers in a patient with osteosarcoma: case report. Tumori. 2011;97(1):109–114. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leidinger B, Bielack S, Koehler G, Vieth V, Winkelmann W, Gosheger G. High level of beta-hCG simulating pregnancy in recurrent osteosarcoma: case report and review of literature. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130(6):357–361. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oshrine BR, Sullivan LM, Balamuth NJ. Ectopic production of beta-hCG by osteosarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36(3):e202–206. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher K, Rojas K, Zelkowitz C, Borgen P, Kiss L, Zeng J. Beta-HCG-producing phyllodes tumor. Breast J. 2020;26(3):547–549. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maryamchik E, Lyapichev KA, Halliday B, Rosenberg AE. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma with rhabdomyosarcomatous differentiation producing hCG: a case report of a diagnostic pitfall. Int J Surg Pathol. 2018;26(5):448–452. doi: 10.1177/1066896918760192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell MJ, Flynt FL, Harroff AL, Fadare O. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma of the retroperitoneum with extensive leiomyosarcomatous differentiation and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin production. Sarcoma. 2008;2008:658090. doi: 10.1155/2008/658090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens EE, Aquino J, Barrow N, Lee YC. Ectopic production of human chorionic gonadotropin by synovial sarcoma of the hip. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 Pt 2 Suppl 1):468–471. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Froehner M, Gaertner HJ, Manseck A, Oehlschlaeger S, Wirth MP. Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma associated with an elevated beta-hCG serum level mimicking extragonadal germ cell tumor. Sarcoma. 2000;4(4):179–181. doi: 10.1080/13577140020025904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansi IA, Ashley I, Glezerov V. Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma and enlarged epididymis associated with a positive pregnancy test. Am J Med Sci. 2002;324(2):104–105. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200208000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ou SM, Lee SS, Peng YJ, Sheu LF, Yao NS, Chang SY. Production of beta-hCG by spermatic cord leiomyosarcoma: a paraneoplastic syndrome? J Androl. 2006;27(5):643–644. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seidl C, Lippert C, Grouls V, Jellinghaus W. [Leiomyosarcoma of the spermatic cord with paraneoplastic beta-hCG production] Pathologe. 1998;19(2):146–150. doi: 10.1007/s002920050267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meredith RF, Wagman LD, Piper JA, Mills AS, Neifeld JP. Beta-chain human chorionic gonadotropin-producing leiomyosarcoma of the small intestine. Cancer. 1986;58(1):131–135. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860701)58:1<131::aid-cncr2820580123>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnan V, Sauthier P, Provencher D, Rahimi K. Pleomorphic undifferentiated uterine sarcoma in a young patient presenting with elevated beta-hCG and rare variants of benign leiomyoma: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2020;39(4):362–366. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsakos E, Xydias EM, Ziogas AC, Bimpa K, Sioutas A, Zarampouka K, Tampakoudis G. Uterine malignant leiomyosarcoma associated with high levels of serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10(9):e6322. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Luigi G, D'Alfonso A, Patacchiola F, Di Stefano L, Palermo P, Carta G. Leiomyosarcoma: a rare malignant transformation of a uterine leiomyoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2015;36(1):84–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fidler IJ. Metastasis: quantitative analysis of distribution and fate of tumor emboli labeled with 125 I-5-iodo-2'-deoxyuridine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1970;45(4):773–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.