Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the death of motor neurons, the aetiology of which is essentially unknown. Here, we present an integrative epigenomic study in blood samples from seven clinically characterised sporadic ALS patients to elucidate molecular factors associated with the disease. We used clinical exome sequencing (CES) to study DNA variants, DNA-RNA hybrid immunoprecipitation sequencing (DRIP-seq) to assess R-loop distribution, and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) to examine DNA methylation changes. The above datasets were combined to create a comprehensive repository of genetic and epigenetic changes associated with the ALS cases studied. This repository is well-suited to unveil new correlations within individual patients and across the entire patient cohort. The molecular attributes described here are expected to guide further mechanistic studies on ALS, shedding light on the underlying genetic causes and facilitating the development of new epigenetic therapies to combat this life-threatening disease.

Subject terms: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Epigenomics

Background & Summary

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that affects the motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord. It is characterised by the progressive degeneration and loss of these motor neurons, leading to a gradual deterioration of muscle control and function. As a result, ALS patients experience muscle weakness, paralysis, and ultimately, difficulty or inability in breathing, swallowing, and speaking. The molecular cause of ALS is complex and not fully understood. Diagnosing the disease is a significant challenge as ALS has similar symptoms to other diseases. Differentiating ALS from these conditions requires a number of medical tests, including genetic testing, electromyography (EMG), as well as MRI scans1. Currently, there are no effective proteomic, RNA, or other biomarkers to provide early predictions for this disorder.

ALS is a rare disease with a worldwide incidence of 1.75 cases per 100 000 person per years of follow-up2. The familial form (representing 5–10% of cases) is linked to specific gene mutations such as SOD1, C9orf72, TARDBP, and FUS, however, the list of discovered ALS gene mutations is continuously growing. The pathogenesis of sporadic ALS, which constitutes the majority of cases (around 90–95%), is less clear and likely involves a combination of genetic and environmental factors3–5. While specific gene mutations are not prevalent in sporadic ALS, genetic variants as risk factors can significantly contribute to disease susceptibility6. Pathogenic or likely-pathogenic variants that individually have only modest effects on ALS risk can collectively contribute to an individual’s predisposition (this concept is best supported by evidence in individuals carrying a p.N352S mutation in TARDBP)7. Common variants with small effect size and combinations of such variants may also confer genetic risk in sporadic ALS patients, but convincing data demonstrating this are still lacking8. Therefore, establishing new genomic data to identify these genetic variants and their combinations in individuals becomes of paramount importance to explain the “missing heritability”6 of high-risk (causative) ALS genes. On the other hand, Mendelian inheritance accounts for only a minority of cases, promoting a focus on environmental and epigenomic cues to explain the missing heritability of known ALS mutations9. In addition to genetic variants, epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation10–13 and R-loops14–20 are highly likely to play a role in the development of sporadic ALS. Although the precise pathophysiological mechanisms by which these factors contribute to motor neuron degeneration remain unclear, they may be applicable as diagnostic markers of the disease.

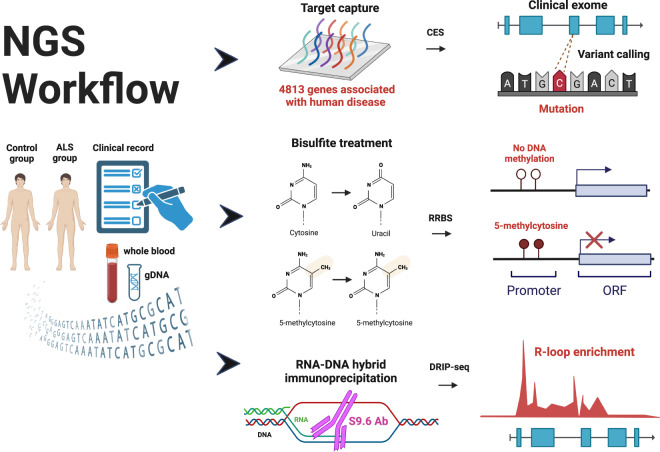

Here, we present a comprehensive epigenomic investigation in blood samples from seven sporadic ALS patients with well-defined clinical characteristics to uncover molecular factors linked to the disease. Our study employed three main techniques: clinical exome sequencing (CES)21 to analyze DNA variants, DNA-RNA hybrid immunoprecipitation sequencing (DRIP-seq)22 to investigate R-loop accumulation, and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS)23 to explore DNA methylation levels (Fig. 1). By combining these datasets, we have compiled a compendium of genomic alterations associated with the studied ALS cases.

Fig. 1.

Outline of the next generation sequencing (NGS) experiments. The workflow began with obtaining blood samples from ALS patients with well-defined clinical records and age-matched control individuals. From these blood samples, genomic DNA was extracted that underwent three simultaneous investigations: 1. Clinical exome sequencing (CES) was performed on 4813 genes commonly linked to human diseases. The protein-coding regions (exons) of the target genes were enriched using target capture microarray hybridization prior to NGS. 2. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) was employed to analyze gene regulatory regions that influence gene transcription through DNA methylation. 3. DNA-RNA hybrid immunoprecipitation sequencing (DRIP-seq) was utilized to capture chromosomal R-loops associated with genic and intergenic regions.

Methods

Patient selection

The clinical diagnosis of ALS cases fulfilled the ‘El Escorial revisited’ clinically definite diagnostic certainty and the complementary ‘Awaji’ criteria for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis24,25. All selected patients are considered to have sporadic ALS, as the disease did not occur in their families (Table 1). We confirm that informed consent was obtained from all subjects and that our experiments were approved by the Medical Research Council (Ministry of Interior, Hungary) in accordance with all relevant ethical and legal requirements (approval numbers: 47066-3/2013/EKU(556/2013); 11920-2/2017/EÜIG; 12702-5/2018/EÜIG). We confirm that the ethics agreement allows for the open publication of anonymized genetic data and the participants understood all risks for the open publication of these data, as per informed consent.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of individuals examined in this study.

| ID | Group | Sex | Age (at the time of sampling) | Age (at the onset of ALS) | Severity (ALSFRS score*) | Duration of ALS (at the time of sampling; month) | ALS symptoms | Sites of ALS symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS61 | ALS | female | 52 | 50 | 38 | 24 | classic (all 3 symptom groups), bulbar, lower and upper limb, pseudobulbar | bulbar: dysarthria, lower MNs > upper MNs |

| ALS62 | ALS | female | 54 | 53 | 34 | 12 | classic (all 3 symptom groups), bulbar, lower and upper limb | lower extremity weakness /right > left/ mainly lower MNs |

| ALS69 | ALS | male | 51 | 49 | 43 | 18 | classic (all 3 symptom groups), bulbar, lower and upper limb | bulbar: dysarthria, lower MNs > upper MNs |

| ALS74 | ALS | female | 45 | 45 | 47 | 1 | lower and upper limb, bulbar not present | bilateral peroneal muscle weakness: difficulty in walking, lower and upper MNs |

| ALS75 | ALS | male | 59 | 57 | 24 | 24 | lower and upper limb, bulbar not present | lower extremity weakness and clumsiness: difficulty in waking, upper and lower MNs |

| ALS76 | ALS | female | 61 | 60 | 40 | 12 | lower and upper limb, bulbar not present | slightly asymmetrical extremity weakness: mainly lower MNs |

| ALS81 | ALS | female | 69 | 67 | 24 | 18 | classic (all 3 symptom groups), bulbar, lower and upper limb | left upper extremity weakness: lower MNs |

| K039 | Ctrl | female | 52 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| K107 | Ctrl | female | 45 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| K128 | Ctrl | male | 51 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| K161 | Ctrl | female | 65 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| K190 | Ctrl | male | 59 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| K257 | Ctrl | female | 61 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| K485 | Ctrl | female | 63 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Five female and two male patients with at least two symptoms of the classic diagnostic hallmarks of ALS were recruited. None of the patients had any other comorbidities. Their median age was 51 years, and the median time from diagnosis to sampling was 15 months. Seven age-matched and gender-matched control individuals were also included in the studies. The severity of the diseases at the time of the onset of ALS patients is based on the ALSFRS* score41. The maximal score is 48: not having any signs and symptoms.

Genomic DNA extraction from whole blood

We prepared aliquots of 1 ml frozen whole blood sample from ALS and control patients and extracted 200 μL of it using the Macherey-Nagel™ NucleoSpin™ Tissue Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, we mixed 200 μL of the whole blood sample with 25 μL of Proteinase K and 200 μL of buffer B3, prewarmed to 65 °C. After vortexing the mixture, we incubated it at 65 °C for 10 minutes. Then, we added 210 μL of ethanol (96 – 100%) to each sample, vortexed again, and loaded the mixture onto a NucleoSpin® Tissue Column placed in a Collection Tube. We centrifuged it for 1 minute at 11,000 × g, followed by washing the silica membrane once with 600 μL of BW buffer and once with 600 μL of B5 buffer. After drying the membrane for five minutes, we eluted the DNA twice with 50 μL of prewarmed (55 °C) elution buffer (5 mM Tris pH 8.5). The same samples were pooled and DNA concentration was measured using a Nanodrop. The samples were then concentrated to 100 μL using a speed vacuum concentrator. Next, the genomic DNA was fragmented by digesting 25ug of DNA in a final volume of 100 μL with HindIII, EcoRI, BsrGI, XbaI, and SspI restriction enzymes at 37 °C for 4 hours. We performed a fragment analysis of 3 μL of the digested sample on a 1% agarose gel stained with GelRed (SigmaAldrich). DNA was cleaned from the enzyme reaction using the Macherey-Nagel™ NucleoSpin™ Gel and PCR Clean-up Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol, eluting the fragmented DNA with 2 × 50 μL of nuclease-free water.

Clinical exome seq

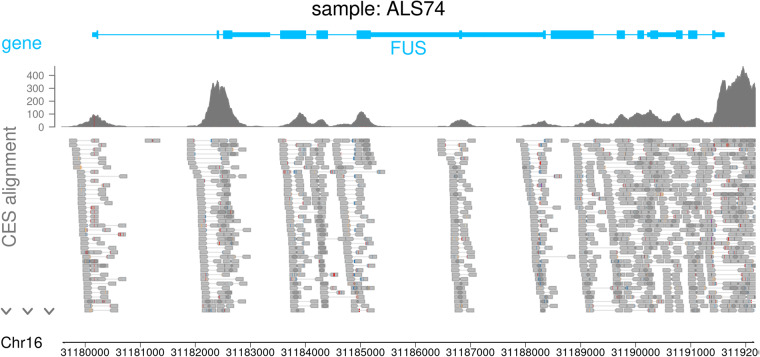

Clinical exome sequencing was performed by TruSight One Sequencing Panel Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) that covers coding regions of 4813 genes associated with human disease. Library preparation was done in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina MiSeq instrument with the 2 × 150 paired-end sequencing mode. Read alignment and sequence variant analysis were performed using NextGENe Software version 2.4.2.3 (SoftGenetics, State College, PA). The reads were mapped against the human GRCh38 (hg38) reference genome. More than 84% of the target regions were observed with least 20-fold coverage. Variants were recorded when a minimum of 5 reads aligned to the variant position, and the variant was observed in at least 20% of those reads (Fig. 2). Variants were annotated using the gnomAD v2.1.1 (GRCh38 LiftOver) database. The clinical interpretation of variants were extracted from the ClinVar (NCBI) database. Analysis results of the samples were obtained from NextGENe as variant call format (vcf) files. Mutation reports (variant lists) were also exported as text tables (.tsv) and then merged, sorted and formatted using R v4.3.1 https://www.R-project.org). Reference files, databases used in the analyses, and non-default software settings are detailed in the Data Records section.

Fig. 2.

Representative clinical exome sequencing result of an ALS patient. Aligned reads are shown over the FUS gene. The list of variants can be found in the Data Records section.

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS)

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) is an established technique for identifying cytosine methylation in genomic regions most relevant to gene regulation. The genomic DNA first undergoes digestion by the MspI restriction enzyme, which recognizes CCGG sites, resulting in genomic fragments starting and ending with a CpG dinucleotide. Since CpGs are unevenly distributed throughout the genome, MspI digestion is followed by size selection that enriches for CpG-rich regions, including CpG islands. These regions are typically located in gene promoters and control gene expression through DNA methylation. We employed the premium RRBS kit of Diagenode to carry out the RRBS protocol including NGS library preparation, as described26,27. Briefly, 100 ng of DNA was fragmented by the MspI restriction enzyme, which cleaves DNA without regard to the cytosine methylation state. Following adaptor ligation and size selection by Ampure beads, we pooled up to 6 samples together. These pooled samples underwent bisulfite treatment, purification, and PCR amplification, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The final RRBS libraries were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay from Life Technologies, and the library’s size distribution profile was assessed using Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 capillary electrophoresis. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument using 1 × 50 single-end mode. Adapter sequences were removed from the raw reads using Trim Galore v0.6.10 https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore (with Cutadapt v4.428). Following an initial quality trimming, sequences were trimmed off the 3′ end of the reads if at least 5 bp overlapped with the adapter sequence. Only reads that were no shorter than 35 bp after trimming were kept. Trim Galore was run in non-directional RRBS mode, which performs additional trimming to avoid using cytosine positions in methylation calls that were filled-in during the end-repair step. Low quality bases at the end of the NGS reads were trimmed off (quality trimming using TrimGalore, see RRBS data processing) before the methylation analysis. After read trimming, bisulfite alignment to the GRCh38 (hg38) reference sequence and methylation calling were performed using Bismark v0.24.129 with bowtie2 v2.3.5.130. After mapping, sam files were sorted using samtools v1.1031.

To investigate methylation level differences between ALS and Control samples, DMSs (differentially methylated sites, per CpG) and DMRs (differentially methylated regions, per 1000 bp window) were identified using the MethylKit v1.26.032 software package (with R v4.3.1. Both methylated and unmethylated CpG cytosines were imported as an input. Then, sites with fewer than 10 mapped reads and sites with exceptionally high coverage above the 99.9 percentile were excluded from the analysis. To ensure comparability between samples, the CpG methylation data were normalised, setting the median coverage to be the same for each sample (Table 2).

Table 2.

Methylation statistics of CpG sites.

| Sample | N | Min | Median | Mean | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS61 | 1622462 | 0 | 31.03 | 45.52 | 100 |

| ALS69 | 576758 | 0 | 35 | 46.18 | 100 |

| ALS74 | 620129 | 0 | 37.04 | 46.69 | 100 |

| ALS75 | 1530019 | 0 | 0 | 28.98 | 100 |

| ALS76 | 1272746 | 0 | 51.28 | 49.34 | 100 |

| ALS81 | 1444033 | 0 | 48 | 48.71 | 100 |

| K039 | 288927 | 0 | 50 | 49.06 | 100 |

| K107 | 1465401 | 0 | 63.64 | 51.84 | 100 |

| K128 | 428690 | 0 | 20 | 43.07 | 100 |

| K161 | 1714994 | 0 | 64.71 | 51.67 | 100 |

| K190 | 762914 | 0 | 71.43 | 53.08 | 100 |

| K257 | 527931 | 0 | 36 | 46.64 | 100 |

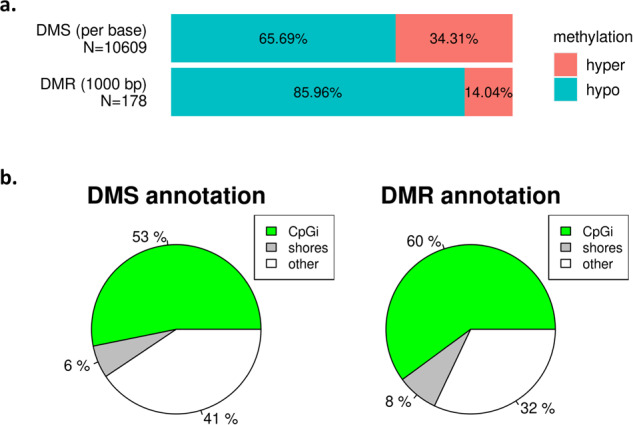

For differentially methylated site (DMS) analysis, each CpG site’s DNA methylation status was evaluated individually33. A CpG site was retained for further analysis only if it had been sequenced and covered in at least 4 samples within each sample group. For the analysis of differentially methylated regions (DMRs), the genome was partitioned into 1000 bp tiling windows with a 1000 bp step-size, and DNA methylation levels were computed for each tiled region. A region was considered for analysis only if it had been sequenced and covered in at least 4 samples within each sample group, and it had a minimum of 5 covered CpG bases. DMS and DMR statistics were calculated by logistic regression using the ‘calculateDiffMeth’ function with default parameters. The threshold for significant methylation differences between sample groups was set to 20%, and the hits were further filtered by a significance value of q <= 0.01. The identified DMSs and DMRs were annotated by the overlapping genic regions, including promoter, exon, intron, and transcription start site (TSS). DMSs and DMRs resulted in extensive coverage of CpG islands (53–60%) and in sequences up to 2 kb distant termed CpG island shores (6–8%)34, while also maintaining substantial coverage of other genomic elements (32–41%) (Fig. 3). Description of all software parameter settings employed in the RRBS analysis, reference data and processed data utilized in the analysis can be found in the Data Records section.

Fig. 3.

Most DNA methylation occurs in CpG islands and in sequences up to 2 kb distant termed CpG island shores. (a) Proportion of hypo- and hypermethylated sites (DMSs) and regions (DMRs) in ALS samples relative to healthy controls. The dominant change is hypomethylation. N: Total number of DMSs and DMRs. (b) Annotation of DMSs and DMRs to CpG islands (CpGi) and CpG shores of the human genome.

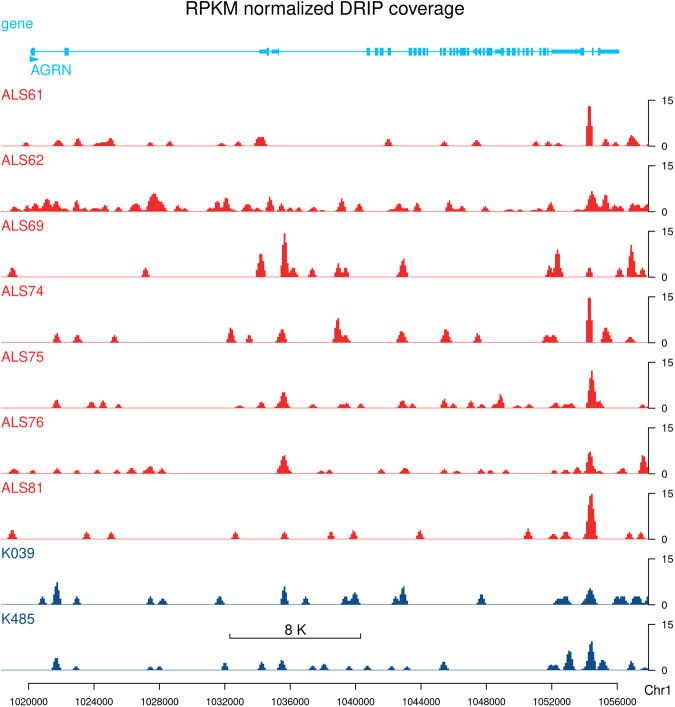

DRIP-seq

DNA-RNA Immunoprecipitation (DRIP) sequencing was started by blocking and coating magnetic beads (Dynal protein G). 2 × 50 μL of protein G beads were washed with 3 × 1 ml of 5 mg/ml PBS/1 mM EDTA/1% BSA solution using a MagnaRack. To the beads, we added 500 µl of 5 mg/ml PBS/1 mM EDTA/1% BSA solution and 25 μg of the RNA-DNA hybrid-specific S9.6 monoclonal antibody35,36. The mixture was incubated for 4 hours with rotation at 4 °C in a cold room and then washed with 1 ml of PBS/1 mM EDTA/1% BSA twice. For immunoprecipitation, we diluted each sample to 700 µl with ChIP lysis Buffer (50 mM Hepes/KOH pH 7,5, 0,14 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0,1% Na-Deoxycholate). We mixed 200 μL of the sample with 500 μL of ChIP lysis Buffer and added 2 × 700 µl of this mixture to 50 µl of S9.6-coated beads. After incubating overnight at 4 °C with rotation, we performed a series of washing steps using different buffers as described22. Finally, the DNA was eluted from the beads by adding 100 µl of IP Elution buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS), vortexing every 2 minutes, and incubating in a thermomixer for 15 minutes at 65 °C. We then used a MagnaRack to separate the supernatant and pipetted it into a new low-binding tube. To further purify the DNA, we conducted a PCR clean-up using the NTB M&N kit, eluting the DNA in 3 × 100 μL of H2O (pH > 7). Before NGS library preparation, we performed further fragmentation through sonication in a 1.5 ml low-bind tube (300 μl sample) using a Bioruptor (Diagenode) with 2 × 4 cycles of 30 seconds ON/OFF at LOW settings. Finally, we concentrated the samples to 30 μL using a speed vacuum concentrator and measured the concentration using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit. NGS library preparation and sequencing was performed as described36,37 using the Illumina TruSeq ChIP Sample Preparation protocol. Briefly, DRIP DNA was end-repaired and indexed adapters were ligated to the inserts. Purified ligation products were then amplified by PCR. Amplified libraries were sequenced (at the EMBL Genomics Core Facility, Heidelberg) using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument in the 2 × 125 paired-end sequencing mode. Quality of raw DRIP-seq reads were checked using FastQC v0.11.9 and the results were summarized using MultiQC v1.1438. DRIP-seq reads were aligned to the GRCh38 (hg38) reference sequence using bowtie2 v2.3.5.130. Alignments were filtered using samtools v1.10 keeping only primary alignments of properly paired reads that had >30 mapping quality score. PCR and optical duplicates were also filtered out. RPKM normalized coverage (bigwig) files have been generated with 100 bp resolution using bamCoverage v3.5.139. A representative genome browser track is shown in Fig. 4. Detailed software parameter settings can be found in the Data Records section.

Fig. 4.

Representative genome browser track showing the RNA-DNA hybrid (R-loop) profile of ALS patients and healthy controls.

Reference data information

All reference data and databases used for CES, RRBS, and DRIP-seq analyses are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reference data and reference databases used in this study.

| Data description | ID/version | Data processing step |

|---|---|---|

| Reference sequence | GRCh38/hg38 (fasta) | read mapping (CES, DRIP, RRBS) |

| Annotation | GRCh38/hg38, build: p13 (gff3) | gene annotation (CES, RRBS) |

| Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database | NCBI dbSNP database | variant ID (CES) |

| Genome Aggregation Database | gnomAD v2.1.1 (GRCh38 LiftOver) | variant annotation (CES) |

| Variant database (clinical) | NCBI ClinVar (2022.11.13) | variant annotation (CES) |

Data Records

All NGS datasets generated in this study (CES, RRBS, DRIP-seq) were deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession number: GSE24247540. A detailed summary of all NGS experiments, NGS data, processed data, result tables, and identifiers to access relevant datasets for RRBS, CES and DRIP-seq can be found in Tables 4–6.

Table 5.

Summary of CES data generated in this study.

| Data description | Tissue | Sample group | Sample ID | SRA/GEO reference | Data collection/Analytical step |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES (fastq) | blood | ALS | ALS61 | SRX21649845 | Clinical exome sequencing, 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads |

| blood | ALS | ALS62 | SRX21649846 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS69 | SRX21649847 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS74 | SRX21649848 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS75 | SRX21649849 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS76 | SRX21649850 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS81 | SRX21649851 | ||

| Clinical exome, gene sequence variations (vcf) | blood | ALS | ALS61 | GSM7764370 | CES read alignment, sequence variant analysis, annotation |

| blood | ALS | ALS62 | GSM7764371 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS69 | GSM7764372 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS74 | GSM7764373 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS75 | GSM7764374 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS76 | GSM7764375 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS81 | GSM7764376 | ||

| Variant list (tsv) | blood | ALS | — | GSE242472 | Merged and reformatted results |

Table 4.

Summary of RRBS data generated in this study.

| Data description | Tissue | Sample group | Sample ID | SRA/GEO reference | Data collection/Analytical step |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRBS (fastq) | blood | ALS | ALS61 | SRX21649976 | Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing, 1 × 50 bp reads |

| blood | ALS | ALS69 | SRX21649977 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS74 | SRX21649978 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS75 | SRX21649979 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS76 | SRX21649980 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS81 | SRX21649981 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K061 | SRX21649982 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K039 | SRX21649983 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K107 | SRX21649984 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K128 | SRX21649985 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K190 | SRX21649986 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K257 | SRX21649987 | ||

| CpG methylation data (txt) | blood | ALS | ALS61 | GSM7764386 | RRBS trimmed read mapping, methylation calling with quality and coverage filtering |

| blood | ALS | ALS69 | GSM7764387 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS74 | GSM7764388 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS75 | GSM7764389 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS76 | GSM7764390 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS81 | GSM7764391 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K061 | GSM7764392 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K039 | GSM7764393 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K107 | GSM7764394 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K128 | GSM7764395 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K190 | GSM7764396 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K257 | GSM7764397 | ||

| Differentially methylated CpG sites (tsv) | blood | ALS vs Ctrl | — | GSE242474 | Coverage filtering and normalization, differential methylation analysis, gene annotation, resolution: per CpG site |

| Differentially methylated regions, 1000 bp (tsv) | blood | ALS vs Ctrl | — | GSE242474 | Coverage filtering and normalization, differential methylation analysis, gene annotation, resolution: 1000 bp tiles |

Table 6.

Summary of DRIP-seq data generated in this study.

| Data description | Tissue | Sample group | Sample ID | SRA/GEO reference | Data collection/Analytical step |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRIP-seq (fastq) | blood | ALS | ALS61 | SRX21651396 | DRIP-sequencing, 2 × 125 bp paired-end reads |

| blood | ALS | ALS62 | SRX21651397 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS69 | SRX21651398 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS74 | SRX21651399 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS75 | SRX21651400 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS76 | SRX21651401 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS81 | SRX21651402 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K039 | SRX21651403 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K485 | SRX21651404 | ||

| DRIP coverage (bw) | blood | ALS | ALS61 | GSM7764377 | DRIP-seq read alignment; quality and duplicate filtering; RPKM-normalized coverage |

| blood | ALS | ALS62 | GSM7764378 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS69 | GSM7764379 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS74 | GSM7764380 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS75 | GSM7764381 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS76 | GSM7764382 | ||

| blood | ALS | ALS81 | GSM7764383 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K039 | GSM7764384 | ||

| blood | Ctrl | K485 | GSM7764385 |

Technical Validation

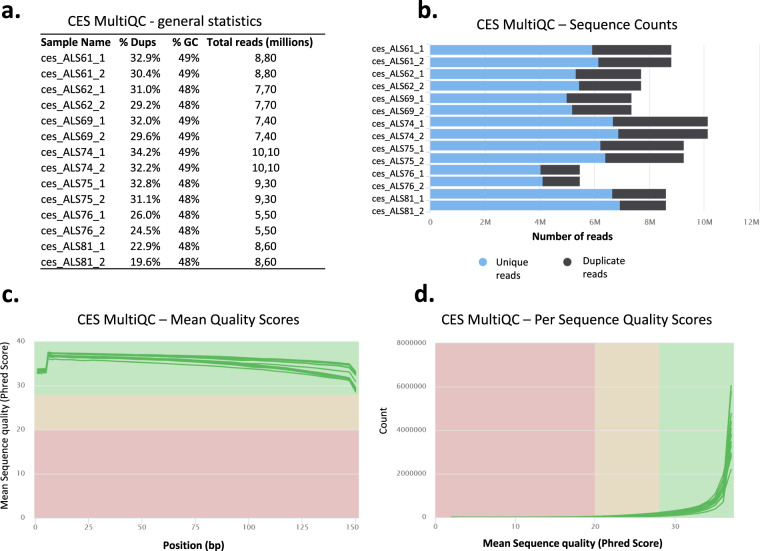

CES was validated by FastQC v0.11.9 and summarized reports were generated using MultiQC v1.1438. Of the 7.4–10,1 million sequenced reads, greater than 60% of NGS reads were unique (Fig. 5a,b). Mean Phred quality scores for each read position in each RRBS sample were high (indicative of ‘very good quality’) (Fig. 5c). Per sequence Phred quality scores were higher than 28 (indicative of ‘very good quality’) for at least 95% of reads in each CES sample (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

MultiQC validation of clinical exome seq (CES) data. (a) General NGS statistics of CES samples. (b) The Sequence Counts plot displays the total count of reads, categorized as either unique or duplicate. Identifying duplicates involves requiring an exact sequence match across the entire sequence length. To conduct this analysis, any reads longer than 75 bp were shortened to 50 bp. (c) Mean quality Phred scores are presented, with higher scores indicating better base calls. The graph’s background color partitions the y-axis into regions denoting very good quality calls (green zone), calls of moderate quality (orange zone), and calls of poor quality (red zone). (d) Per sequence quality Phred scores are depicted, indicating whether a subset of sequences exhibits consistently low-quality values. The background color of the graph distinguishes very good quality calls (green), moderate quality calls (orange), and poor quality calls (red).

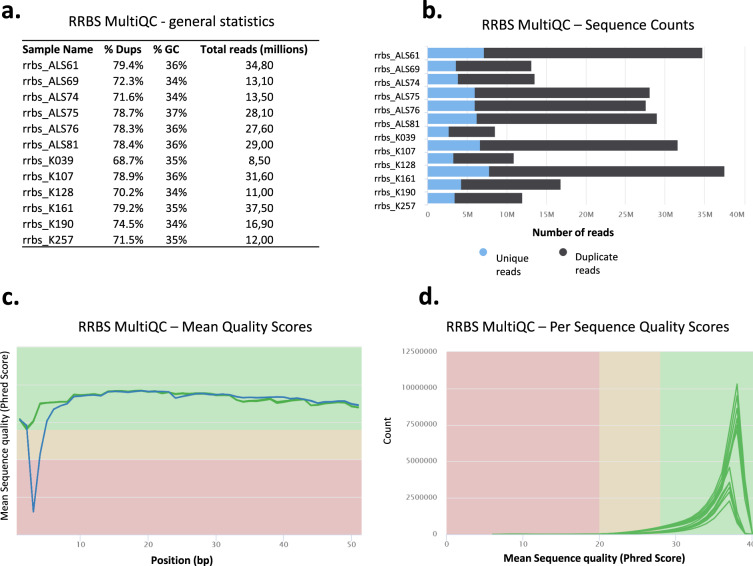

In the RRBS setting, 8.5–37,0 million of sequenced reads were obtained (Fig. 6a). Duplication detection indicated 20–30% of NGS reads as unique (Fig. 6b). Mean Phred quality scores for each read position in each RRBS sample were higher than 28 (indicative of ‘very good quality’) (Fig. 6c). Per sequence Phred quality scores were higher than 28 (indicative of ‘very good quality’) for at least 95% of reads in each RRBS sample (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

MultiQC validation of reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) data. (a) General NGS statistics of RRBS samples. (b–d) Same as in Fig. 2.

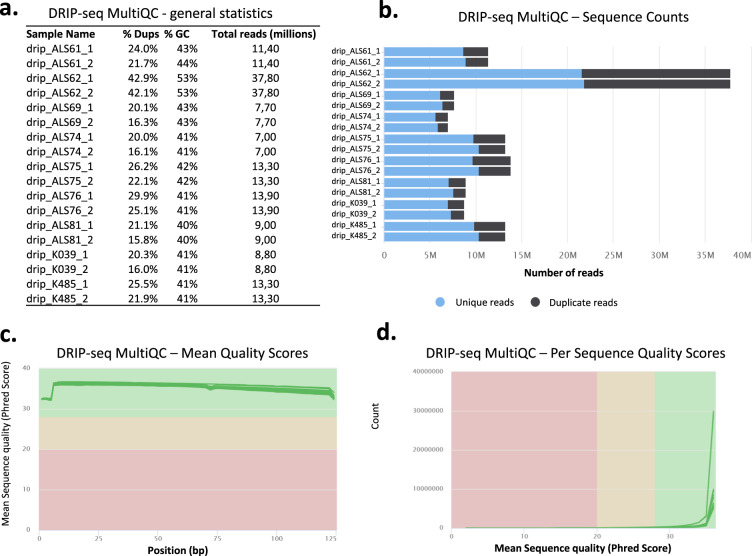

For the DRIP-seq experiments, raw sequence coverage ranged from 7.0–37.7 million reads (Fig. 7a), of which greater than 70 percent qualified as unique (Fig. 7b). Mean and Per sequence Phred quality scores for each read position in each DRIP-seq sample were high (indicative of ‘very good quality’) (Fig. 7c,d).

Fig. 7.

MultiQC validation of DNA-RNA hybrid immunoprecipitation (DRIP) sequencing data. (a) General NGS statistics of DRIP-seq samples. (b–d) Same as in Fig. 2.

Usage Notes

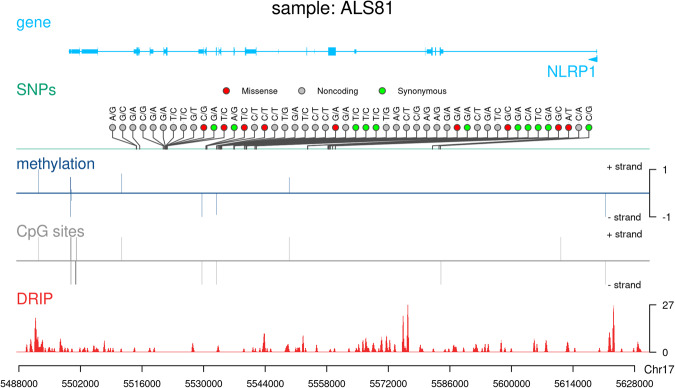

The NGS results presented above reveal three distinct data layers in a small group of ALS patients, encompassing genetic changes, DNA methylation alterations, and R-loop modifications. Obtaining such data from individual patients is crucial as it enables the correlation of these variables both within and between individuals (Fig. 8). Such a correlative analysis is expected to unveil significant epigenetic patterns, potentially explaining the missing heritability (Mendelian inheritance) of gene mutations identified in ALS. The data presented here have been established using widely recognized software tools, making them readily adaptable for integration into any genome analysis workflow. We are confident that the data we provide can contribute to better understand the aetiology of this devastating disease .

Fig. 8.

Correlative analysis of CES, RRBS, and DRIP profiles in ALS patients. Lolliplots show the mutational spectra (SNPs) of the displayed gene (Reference base/Alternate base). Missense, synonymous, and noncoding variants are shown in different colours. DNA methylation is represented by the ratio of methylated/unmethylated CpG dinucleotides. + values: fw strand; - values: reverse strand. The position of CpG sites are shown as a proxy. DRIP stands for the RPKM normalized read coverage of RNA-DNA hybrid (R-loops) levels over the genomic region.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by E-RARE-3 2018 Repetomics, NKFIH-K-142137, NKFIH-NNE-130913, NKFIH-K-132695, and the Thematic Excellence Programmes TKP2021-EGA-18 (L.Sz.) and TKP2021-EGA-20 (G.H.) that have been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-EGA and TKP2021-EGA funding schemes. L.Sz. was supported by the Bolyai Janos fellowship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. We are grateful for the Genomic Medicine and Bioinformatics Core Facility (University of Debrecen) for the NGS service.

Author contributions

D.N., É.N., É.S., B.V. performed the experiments, J.E., N.T., L.V. clinically characterized the ALS patients and established the ALS biobank samples, O.F., I.L., Á.F., T.A., I.B., Zs.K., Z.Sz., G.H. analysed the data, T.A. and L.Sz. secured funding, L.Sz. supervised the work and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Debrecen.

Code availability

No custom code was generated or applied for analysis of the genomic data presented. All software tools used for the analyses and the applied parameter settings are detailed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of software tools used in the current study.

| Software version | Data processing step | Parameter settings |

|---|---|---|

| TrimGalore v0.6.10; cutadapt v4.4 | Read trimming (RRBS) | –quality 20–stringency 5–length 35–non_directional–rrbs |

| Bismark v0.24.1; bowtie2 v2.3.5.1 | Bisulfite alignment (RRBS) | reference sequence: GRCh38; -N 1 |

| samtools v1.10 | Alignment sorting (RRBS) | — |

| MethylKit v1.26.0; R v4.3.1 | Methylation calling (RRBS) | processBismarkAln(): read.context = CpG, mincov = 10 |

| Methylation data filtering and normalization (RRBS) | filterByCoverage(): lo.count = 10, hi.perc = 99.9; normalizeCoverage(): method = “median” | |

| DMS analysis (RRBS) | unite(): min.per.group = 4 L, destrand = TRUE; calculateDiffMeth(): default parameters; getMethylDiff(): difference = 20, qvalue = 0.01 | |

| DMR analysis (RRBS) | tileMethylCounts(): win.size = 1000, step.size = 1000, cov.bases = 5; unite(): min.per.group = 4 L; calculateDiffMeth(): default parameters; getMethylDiff(): difference = 20, qvalue = 0.01 | |

| NextGENe 2.4.2.3 | Read alignment (CES) | reference sequence: GRCh38 |

| Variant calling (CES) | >5 reads/variant position; >20% of reads present the variant | |

| Variant annotation (CES) | databases: NCBI dbSNP; gnomAD v2.1.1 (GRCh38 LiftOver); NCBI ClinVar (2022.11.13) | |

| Gene annotation (CES) | annotation database: GRCh38.p13 | |

| R v4.3.0 | Data formatting (CES) | — |

| bowtie2 v2.3.5.1 | Read alignment (DRIP) | reference sequence: GRCh38 |

| samtools v1.10 | Alignment filtering (DRIP) | view -q30 -f3 -F3840 |

| bamCoverage v3.5.1 | Normalized coverage (DRIP) | –normalizeUsing RPKM–binSize 100–smoothLength 300 |

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Orsolya Feró, Dóra Varga.

Contributor Information

Tamás Arányi, Email: aranyi.tamas@ttk.hu.

Lóránt Székvölgyi, Email: lorantsz@med.unideb.hu.

References

- 1.Strong MJ, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis - frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD): Revised diagnostic criteria. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2017;18:153–174. doi: 10.1080/21678421.2016.1267768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marin, B. et al. Variation in worldwide incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. dyw061 10.1093/ije/dyw061 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Cirulli ET, et al. Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science. 2015;347:1436. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki N, Nishiyama A, Warita H, Aoki M. Genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: seeking therapeutic targets in the era of gene therapy. J. Hum. Genet. 2023;68:131–152. doi: 10.1038/s10038-022-01055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner MR, et al. Controversies and priorities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:310–322. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70036-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Daele, S. H. et al. Genetic variability in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 120 10.1093/brain/awad120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Van Blitterswijk M, et al. Evidence for an oligogenic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:3776–3784. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leblond CS, Kaneb HM, Dion PA, Rouleau GA. Dissection of genetic factors associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 2014;262:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goutman SA, et al. Emerging insights into the complex genetics and pathophysiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:465–479. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00414-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruf WP, et al. Methylome analysis of ALS patients and presymptomatic mutation carriers in blood cells. Neurobiol. Aging. 2022;116:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2022.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yazar V, et al. DNA Methylation Analysis in Monozygotic Twins Discordant for ALS in Blood Cells. Epigenetics Insights. 2023;16:25168657231172159. doi: 10.1177/25168657231172159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin LJ, Adams DA, Niedzwiecki MV, Wong M. Aberrant DNA and RNA Methylation Occur in Spinal Cord and Skeletal Muscle of Human SOD1 Mouse Models of ALS and in Human ALS: Targeting DNA Methylation Is Therapeutic. Cells. 2022;11:3448. doi: 10.3390/cells11213448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hop PJ, et al. Genome-wide study of DNA methylation shows alterations in metabolic, inflammatory, and cholesterol pathways in ALS. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14:eabj0264. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor P, Salvi JS, Mekhail K. R-loops highlight the nucleus in ALS. Nucl. Austin Tex. 2015;6:37–41. doi: 10.1080/19491034.2015.1004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood M, et al. TDP-43 dysfunction results in R-loop accumulation and DNA replication defects. J. Cell Sci. 2020;133:jcs244129. doi: 10.1242/jcs.244129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunseich C, et al. Senataxin Mutation Reveals How R-Loops Promote Transcription by Blocking DNA Methylation at Gene Promoters. Mol. Cell. 2018;69:426–437.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farg MA, Konopka A, Soo KY, Ito D, Atkin JD. The DNA damage response (DDR) is induced by the C9orf72 repeat expansion in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:2882–2896. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kannan A, Cuartas J, Gangwani P, Branzei D, Gangwani L. Mutation in senataxin alters the mechanism of R-loop resolution in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 4. Brain. 2022;145:3072–3094. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Székvölgyi L, et al. Nick-forming sequences may be involved in the organization of eukaryotic chromatin into approximately 50 kbp loops. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2006;125:63–73. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hetey S, et al. Biophysical characterization of histone H3.3 K27 M point mutation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;490:868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H, et al. Clinical Exome Sequencing for Genetic Identification of Rare Mendelian Disorders. JAMA. 2014;312:1880–1887. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halász L, et al. RNA-DNA hybrid (R-loop) immunoprecipitation mapping: an analytical workflow to evaluate inherent biases. Genome Res. 2017;27:1063–1073. doi: 10.1101/gr.219394.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meissner A, et al. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing for comparative high-resolution DNA methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5868–5877. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa J, Swash M, De Carvalho M. Awaji Criteria for the Diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Arch. Neurol. 2012;69:1410. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL. El Escorial revisited: Revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293–299. doi: 10.1080/146608200300079536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veillard A-C, Datlinger P, Laczik M, Squazzo S, Bock C. Diagenode® Premium RRBS technology: cost-effective DNA methylation mapping with superior coverage. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:i–ii. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payen C, et al. Pathophysiological adaptations of resistance arteries in rat offspring exposed in utero to maternal obesity is associated with sex-specific epigenetic alterations. Int. J. Obes. 2021;45:1074–1085. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00777-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal. 2011;17:10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krueger F, Andrews SR. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1571–1572. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danecek P, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 2021;10:giab008. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akalin A, et al. methylKit: a comprehensive R package for the analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R87. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pagliaroli L, et al. Riluzole Administration to Rats with Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesia Leads to Loss of DNA Methylation in Neuronal. Genes. Cells. 2021;10:1442. doi: 10.3390/cells10061442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irizarry RA, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:178–186. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bou-Nader C, Bothra A, Garboczi DN, Leppla SH, Zhang J. Structural basis of R-loop recognition by the S9.6 monoclonal antibody. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29187-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karányi Z, et al. NODULIN HOMEOBOX is required for heterochromatin homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:5058. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32709-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feró O, et al. Coding and noncoding transcriptomes of NODULIN HOMEOBOX (NDX)-deficient Arabidopsis inflorescence. Sci. Data. 2023;10:364. doi: 10.1038/s41597-023-02279-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ewels P, Magnusson M, Lundin S, Käller M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2016;32:3047–3048. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramírez F, et al. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W160–W165. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feró O, 2024. GEO. //identifiers.org/geo/GSE242475

- 41.Cedarbaum JM, et al. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999;169:13–21. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(99)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Feró O, 2024. GEO. //identifiers.org/geo/GSE242475

Data Availability Statement

No custom code was generated or applied for analysis of the genomic data presented. All software tools used for the analyses and the applied parameter settings are detailed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of software tools used in the current study.

| Software version | Data processing step | Parameter settings |

|---|---|---|

| TrimGalore v0.6.10; cutadapt v4.4 | Read trimming (RRBS) | –quality 20–stringency 5–length 35–non_directional–rrbs |

| Bismark v0.24.1; bowtie2 v2.3.5.1 | Bisulfite alignment (RRBS) | reference sequence: GRCh38; -N 1 |

| samtools v1.10 | Alignment sorting (RRBS) | — |

| MethylKit v1.26.0; R v4.3.1 | Methylation calling (RRBS) | processBismarkAln(): read.context = CpG, mincov = 10 |

| Methylation data filtering and normalization (RRBS) | filterByCoverage(): lo.count = 10, hi.perc = 99.9; normalizeCoverage(): method = “median” | |

| DMS analysis (RRBS) | unite(): min.per.group = 4 L, destrand = TRUE; calculateDiffMeth(): default parameters; getMethylDiff(): difference = 20, qvalue = 0.01 | |

| DMR analysis (RRBS) | tileMethylCounts(): win.size = 1000, step.size = 1000, cov.bases = 5; unite(): min.per.group = 4 L; calculateDiffMeth(): default parameters; getMethylDiff(): difference = 20, qvalue = 0.01 | |

| NextGENe 2.4.2.3 | Read alignment (CES) | reference sequence: GRCh38 |

| Variant calling (CES) | >5 reads/variant position; >20% of reads present the variant | |

| Variant annotation (CES) | databases: NCBI dbSNP; gnomAD v2.1.1 (GRCh38 LiftOver); NCBI ClinVar (2022.11.13) | |

| Gene annotation (CES) | annotation database: GRCh38.p13 | |

| R v4.3.0 | Data formatting (CES) | — |

| bowtie2 v2.3.5.1 | Read alignment (DRIP) | reference sequence: GRCh38 |

| samtools v1.10 | Alignment filtering (DRIP) | view -q30 -f3 -F3840 |

| bamCoverage v3.5.1 | Normalized coverage (DRIP) | –normalizeUsing RPKM–binSize 100–smoothLength 300 |