Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

We compared white matter hyperintensities (WMH) in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD) with cognitively normal (CN) and early-onset amyloid-negative cognitively impaired (EOnonAD) groups in the Longitudinal Early-onset Alzheimer Disease Study.

METHODS:

We investigated the role of increased WMH in cognition and amyloid and tau burden. We compared WMH burden of 205 EOAD, 68 EOnonAD, and 89 CN participants in lobar regions using t-tests and analyses of covariance. Linear regression analyses were used to investigate the association between WMH and cognitive impairment, and amyloid and tau burden.

RESULTS:

EOAD showed greater WMH compared with CN and EOnonAD participants across all regions with no significant differences between CN and EOnonAD groups. Greater WMH were associated with worse cognition. Tau burden was positively associated with WMH burden in the EOAD group.

DISCUSSION:

EOAD consistently showed higher WMH volumes. Overall, greater WMH were associated with worse cognition and higher tau burden in EOAD.

Keywords: WMH, EOAD, tau positron emission tomography, tau PET, amyloid, white matter hyperintensities, Alzheimer’s Disease

1. Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often used to visualize structural changes in the brain associated with aging. White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) presenting as areas of comparatively high T2-weighted image intensities are commonly associated with small vessel cerebrovascular disease due to increasing age and greater cardiovascular risk factors. In recent years, several studies examined the association between WMH burden and clinical presentation of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) showing associations between WMH volume and the clinical symptoms1,2. The accumulation of WMHs in people with LOAD may reflect the presence of multiple pathologies3. A recent study4 emphasized the role of increased WMH volume as a unique determinant of cognitive performance in autosomal-dominant early-onset AD (EOAD).

Associations between WMHs and amyloid burden measured by positron emission tomography (PET) inform the effect of cerebral amyloid angiopathy on increased WMH load in the brain. The mediating effect of cerebral microbleeds on the relationship between estimated disease onset and the WMH load was considered5 in the context of dominantly-inherited AD using data from participants with 50% chance of developing AD since they have a first-degree relative diagnosed with AD autosomal dominant, fully-penetrant genetic mutation. The results indicate that the increase in WMHs in those with the mutation is not fully explained by presence of microbleeds5. Using data from cognitively unimpaired elderly participants in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, the topographic patterns of WMHs were analyzed6 showing that amyloid associated WMH volumes were localized in frontal and parietal lobes. In the meantime, increased volumes of WMH were associated with changes in plasma tau in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) LOAD study7. In addition, the association between WMHs and tau burden in tandem with presence of amyloid in the brain was predictive of AD diagnosis7.

Compared to older individuals, WMHs are uncommon in young and healthy adults. For instance, a 10-fold increase in WMH was found8 in people over 55 years of age as compared to those less than 55 years of age. While it has been hypothesized that presence of WMH in younger individuals may associate with cognitive decline, the extent of WMHs in people with sporadic EOAD and their relationship with cognitive decline has not been evaluated in large sample studies. A case report study9 investigated the increased burden of WMH and brain atrophy looking for causative gene mutations. While causative genes associated with WMH burden and distribution of WMH were identified, the number of participants with the mutation included in the presented analyses was only seven, raising questions about generalizability of the results given the small sample size.

The Longitudinal Early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease study10 (LEADS) aims to inform characteristic biomarkers of EOAD. We considered the spatial distribution of WMH in EOAD and its differences from average WMH of cognitively normal (CN) and early-onset amyloid-negative cognitively impaired (EOnonAD) groups. We investigated associations between WMH burden and cognitive performance of participants in LEADS where cognitive status was evaluated using clinical dementia rating (CDR®) sum-of-box scores, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE). In addition, we considered potential associations between amyloid and tau burden from PET scans and WMH volumes looking for potential differences in the strengths of these relationships between diagnosis groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

We analyzed data from 362 participants from the LEADS study accrued since 2018. From the 371 participants included in the LEADS mid-term analysis, nine were missing WMH volumes and were excluded from subsequent analyses. The sample includes 205 EOAD, 68 EOnonAD, and 89 CN participants from LEADS. Participants were eligible for LEADS enrollment if their age was between 40- and 64-years, they had a reliable study partner, were English speaking, and had no known psychiatric disorders or other neurological issues. A global CDR score of ≤ 1 was the enrollment criterion for the cognitively impaired group while the cognitively normal group includes participants with a global CDR score of 0 and MMSE ≥26. Individuals with pathogenic variants in PSEN1, PSEN2, APP, MAPT, GRN and C9ORF72 were excluded from the analyses. Summaries of demographic and clinical scores are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

CN, EOAD, and EOnonAD demographic and cognitive summaries, presented as mean (standard deviation, and comparisons. The last three columns represent t-statistics (p-values) from analyses comparing the respective groups for continuous variables, while binary variable comparisons show test statistics (p-values) from Chi-squared tests.

| CN | EOAD | EOnonAD | CN vs EOAD |

CN vs EOnonAD |

EOAD vs EOnonAD |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 89(24.6%) | 205 (56.6%) | 68 (18.8%) | |||

| Age, years | 56.13 (6.02) | 58.79 (3.94) | 58.1 (5.85) | −3.82 (<0.01) | −2.05 (0.04 ) | 0.90 (0.37) |

| Sex (% F) | 61.8% | 52.7% | 33.8% | 2.09 (0.1) | 12.07 (<0.01) | 7.28 (<0.01) |

| Minority (%) | 29.2% | 7.8% | 13.2% | 23.51 (<0.01) | 5.86 (0.016) | 1.78 (0.18) |

| Hispanic (%) | 7.9% | 2.9% | 2.9% | 3.58 (0.058) | 1.73 (0.19) | 0.00 (0.99) |

| Education, years | 16.67 (2.18) | 15.38 (2.36) | 15.32 (2.58) | 4.44 (<0.01) | 3.55 (<0.01) | 0.15 (0.88) |

| MMSE | 29.19 (0.94) | 21.92 (4.99) | 25.47 (4.35) | 20.06 (<0.01) | 6.94 (<0.01) | −5.24 (<0.01) |

| CDR Global 0.5/1.0, % | 0%/0% | 66%/34% | 79%/21% | 4.41 (0.036) |

2.2. MRI acquisition and analysis

According to the LEADS protocols, 3D MRI sequences were obtained from each participant. Details on MRI acquisition protocol are provided elsewhere10. Briefly, data were acquired using 3 Tesla scanners at all LEADS data collection sites supported by the LEADS MRI Core. Sagittal 3D magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequences were obtained using TR/TE/TI = 2300/3/900 ms with flip angle of 9 degrees, sagittal orientation, and FOV = 256 × 240 mm with 208 slices using 1 × 1 × 1 mm resolution. Sagittal 3D fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences were acquired with TR/TE/TI = 4800/119/1650 ms, FOV = 256 × 256 mm with 160 slices, at resolution 1.2 × 1 × 1 mm. A fully automatic algorithm11 was implemented to calculate WMH volumes from the 3D MPRAGE and FLAIR images. WMHs were segmented on the native FLAIR images via automated seed initialization based on their location using spatial priors, incorporating intensity relative to the distribution of GM intensity values, and that of its local neighborhood. To reduce false-positive WMH segmentations, a WM mask derived from automated MPRAGE segmentation with SPM12 was applied, in addition to using region-growing. For each ROI, total WMH volume was calculated as cm3 and scaled by the total intracranial volume (TIV) to adjust for head size.

2.3. PET Acquisition and Preprocessing

Positron emission tomography (PET) images were obtained from all participants for β-amyloid (18F-Florbetaben) and tau (18F-Flortaucipir). PET acquisition protocols were described previously10. About 90 to 110 minutes after injection of ~8 mCi of 18F-Florbetaben the amyloid PET images were acquired at four 5-minute frames, while 18F-Flortaucipir was acquired between 75 and 105 minutes after injection of about 10 mCi of the corresponding tracer. After quality control procedures, images were pre-processed by realignment and averaging, changing to a standard orientation, and smoothing.

2.4. Statistical Methods

WMHs were used in the analyses as proportion of TIV. Given the skewed distribution of resulting TIV-corrected WMH volumes, the cubic-root transformation was implemented before analyses12. Average cubic-root transformed WMH as proportion of TIV in left and right frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital regions was compared between CN, EOAD, and EOnonAD groups, as well as the sums of left and right regions using t-tests. Similarly, total WMH burden was compared between participants with cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia using t-tests. WMH burden differences were considered between men and women within each diagnostic group using t-tests. Analysis of covariance was implemented to perform similar comparisons while controlling for the effects of age, education, and sex. In addition, using linear regressions, we tested whether there was a significant association between WMH burden and global cognitive impairment measured by MMSE, MoCA, and CDR-SB. Linear regression analyses were used to investigate the association between cognitive impairment as well as amyloid and tau PET burden with WMH load after correcting for the effects of age, sex, TIV, and education. The p-values for WMH comparisons were corrected for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (FDR) method where appropriate.

3. Results

The average age of participants was 57.63. On average, CN participants (56.13, SD = 6.02) were younger than those in the EOAD group (58.79, SD = 3.94; p<0.01) and in the EOnonAD group (58.1, SD = 5.85; p = 0.04; Table 1). Females comprised 61.8% of the CN group, 52.7% of the EOAD group, and 33.8% of the EOnonAD group. While there was no statistically significant difference between sex distribution in CN and EOAD participants (p=0.10), we found the CN and EOAD groups included more female participants compared with EOnonAD (ps<0.01). The CN group included more minority and Hispanic participants compared with EOAD and EOnonAD (ps<0.01). The CN group had greater years of education by 1.29 on average compared to the EOAD group (t-statistic = 4.44, p<0.01). The performance of the participants on MMSE was significantly worse in the EOAD group compared to the EOnonAD (t-statistic = -5.42, p<0.01). The global CDR was different between the diagnosis groups (p=0.048).

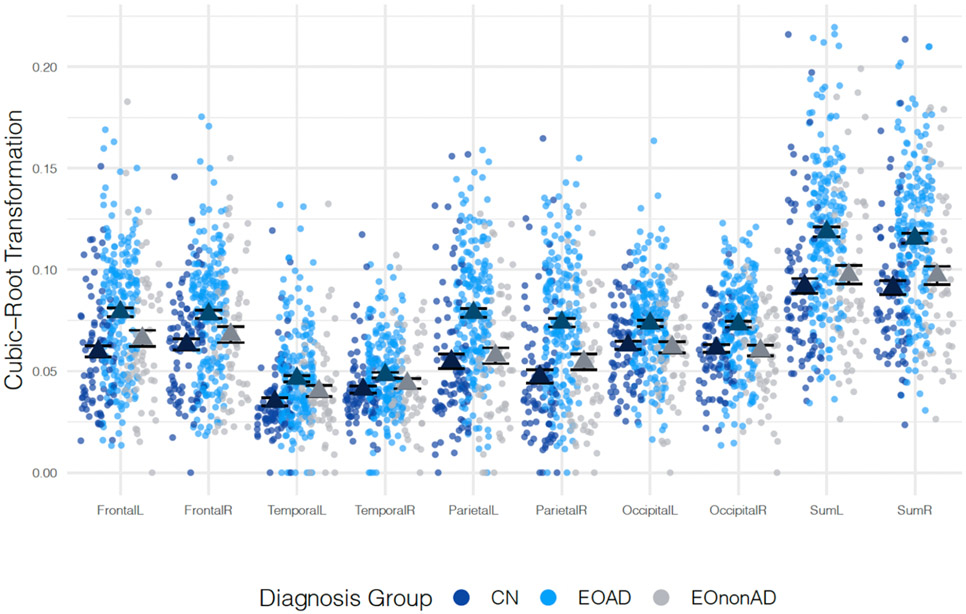

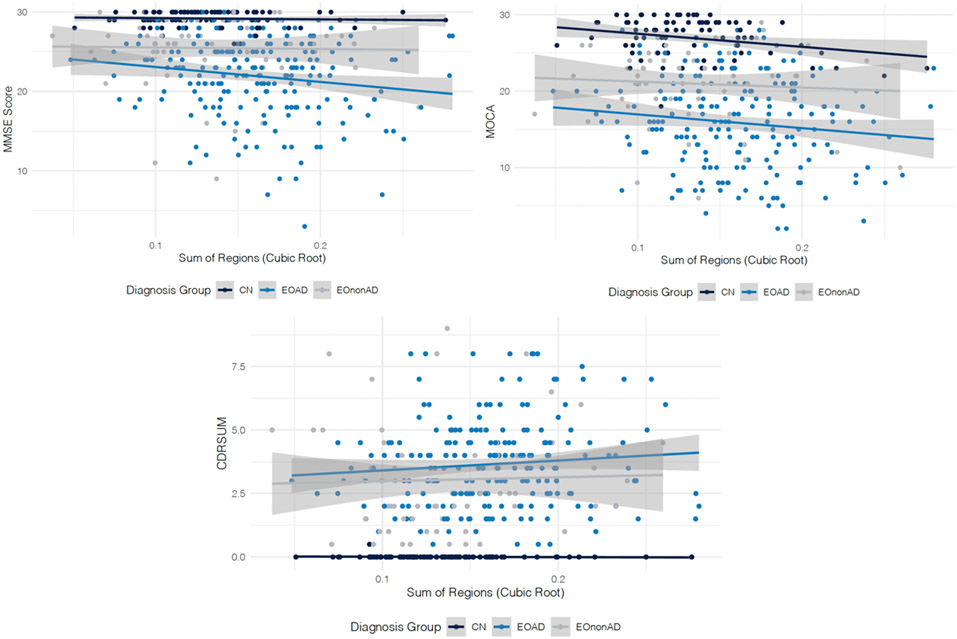

Within the EOAD group the spatial distribution of WMHs was similar within each region’s left and right hemispheres. However, WMH volume was highest in the frontal and parietal regions (no significant differences between WMH burden of frontal and parietal regions, p = 0.90) followed by the occipital region that had lower WMH volumes (p =0.07). The WMH burden in EOAD was lowest in the temporal regions. EOAD participants had significantly greater WMH volumes on average compared with CN and EOnonAD participants across all regions (Figure 1 and Table 2, all p-values<0.05). The WMH burden in the temporal region (left and right) was not significantly different between EOAD and EOnonAD groups, however, given the relatively small sample size, this difference warrants further investigation. No significant differences were observed between average WMHs of CN and EOnonAD groups. The differences between EOAD compared with CN or EOnonAD groups were largest in frontal, parietal, and occipital regions. No significant differences were identified between WMH burden of participants with diabetes compared to those without diabetes (p-value = 0.33 for CN, 0.55 for EOAD, 0.56 for EOnonAD), similarly for hypertension (p-value = 0.14 for CN, 0.31 for EOAD, and 0.81 for EOnonAD), and hypercholesterolemia (p-value = 0.12 for CN, 0.66 for EOAD, and 0.75 for EOnonAD). Although on average TIV corrected WMH burden was slightly higher in women than men, no significant differences were identified between WMH burden of men and women (p-value = 0.62 for CN, 0.23 for EOAD, and 0.96 for EOnonAD) in the study. Higher WMH values were associated with worse performance on MMSE (b = −0.24, SE = 0.06, p-value<0.01) after controlling for the effects of age, sex, TIV, and education. Similarly, higher values of WMH were associated with worse performance on CDR sum-of-boxe scores (b=0.08, SE =0.02, p-value<0.01) and MoCA (b = −0.33, SE = 0.08, p-value<0.01). These observed relationships held after controlling for the effect of diagnosis. Figure 2a, b, and c show the relationships of clinical scores by diagnosis. As illustrated in Figure 2a we observe a steep decline of MMSE as WMH volume increases in the EOAD group while the slopes of the association of WMH and MMSE within the CN and EOnonAD groups are flat. Figure 2b shows that as WMH volumes increase, the scores on MoCA decrease for all three groups. Finally, as sum of WMHs over all regions increases, CDR sum-of-box scores increases both in the EOAD and EOnonAD groups, while remaining flat for the CN group as shown in Figure 2c.

Figure 1:

Comparisons of cubic root-transformed WMH values between CN, EOAD, and EOnonAD participants. The means for each group are presented in triangles.

Table 2:

Comparisons of region-specific cubic root-transformed WMH between CN, EOAD, EOnonAD participants presented as t-statistic (p-value). All p-values are computed using t-tests and are corrected for multiple comparisons using the FDR correction. The average (SD) WMH volumes are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

| Region | CN vs EOAD | EOAD vs EOnonAD |

CN vs EOnonAD |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal | Left | −5.1 (<0.001) | 2.95 (0.005) | −1.33 (0.50) |

| Frontal | Right | −4.05 (<0.001) | 2.34 (0.025) | −0.99 (0.50) |

| Temporal | Left | −4.49 (<0.001) | 1.87 (0.069) | −1.61 (0.50) |

| Temporal | Right | −3.03 (0.027) | 1.52 (0.13) | −0.98 (0.50) |

| Parietal | Left | −6.04 (<0.001) | 4.94 (<0.001) | −0.51 (0.76) |

| Parietal | Right | −6.84 (<0.001) | 4.48 (<0.001) | −1.43 (0.50) |

| Occipital | Left | −3.94 (<0.001) | 3.72 (<0.001) | 0.27 (0.79) |

| Occipital | Right | −4.51 (<0.001) | 4.2 (<0.001) | 0.3 (0.79) |

| Sum | Left | −5.95 (<0.001) | 4.19 (<0.001) | −0.94 (0.50) |

| Sum | Right | −5.66 (<0.001) | 3.72 (<0.001) | −1.08 (0.50) |

Figure 2:

Associations between WMH volume and global cognitive measures in each diagnostic group (CN - in dark blue, EOAD - in blue, and EOnonAD - gray). The regression lines showing the relationship between the WMH volume and each cognitive measure within each diagnostic group are presented, along with a light gray colored confidence band.

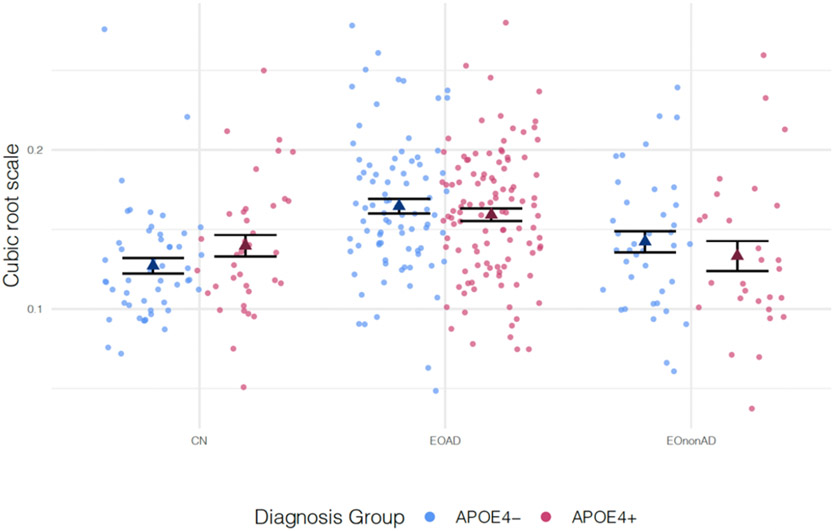

Figure 3 shows the distribution of WMH volumes between APOEε4 carriers and non-carriers by diagnosis group. APOE4 carrier status was not associated with WMH volume after controlling for the effects of age, sex, TIV, the interaction between APOE allele status and diagnosis group, and years of education (β = 1.63, SE = 1.01, p-value = 0.107). In addition, considering each diagnosis category, after fixing age, sex, and education to the same value we did not find significant differences of WMH between APOE4 carriers and non-carriers.

Figure 3:

Comparisons of cubic root-transformed WMH volumes between APOE4− and APOE4+ participants. The means for each group are presented as triangles.

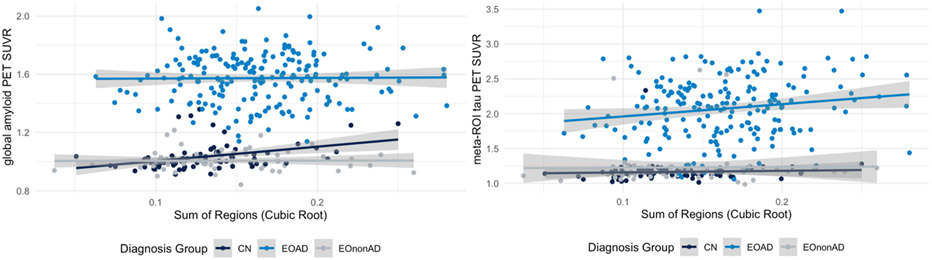

We next investigated the association between WMH volume (sum of regions) and amyloid and tau PET burden. In the sample including all participants, increased WMH volumes were associated with increased amyloid burden (β = 0.02, p-value<0.01) and increased tau burden (β = 0.04, p<0.01) after controlling for the effect of age, sex, TIV, and education. However, after controlling for the effect of diagnosis group, amyloid burden measured using average MRI-based composite SUVR was not significantly associated with WMH volume (β = 0.001, p-value = 0.639). These associations are presented in Figure 4. In the meantime, tau burden remained associated with WMH volume (β = 0.01, SE = 0.005, p-value = <0.01), after controlling for participant diagnosis. Specifically, tau burden was significantly associated with WMH evaluated using the sum of regions in the EOAD group (β = 0.02, SE = 0.006, p-value = <0.01).

Figure 4:

Association between amyloid PET (left column) and tau PET (right column) and log-transformed WMH values within CN, EOAD, and EOnonAD groups.

4. Discussion

EOAD participants enrolled in LEADS had higher WMH burden in comparison to their CN and EOnonAD peers which was associated with worse cognitive performance and greater tau burden. The regional distribution of WMH in EOAD was higher in the parietal and frontal regions followed closely by occipital regions, although this could be related to the differences in total volumes of the corresponding regions. These findings are consistent with the literature showing a similar distribution of WMH in older individuals with AD13. On the contrary, the WMH volume in temporal regions was significantly lower. EOAD consistently showed higher WMH volumes compared to their CN and EOnonAD peers in all brain ROIs considered in this study. The extent of WMH in CN and EOnonAD groups was generally similar, although EOnonAD on average had higher WMH burden than CN participants in all regions except for the occipital lobe. These differences were not statistically significant. EOAD had significantly higher WMH than CN across all brain regions with the largest differences in parietal and frontal regions. This finding is consistent with the literature showing higher WMH volumes in people with dementia14. The biggest differences between average WMH burden of CN and EOAD groups were in the parietal lobes (both left and right regions).

Higher WMHs were associated with worse cognitive impairment measured using MMSE, MoCA, and CDR sum-of-box scores. Associations between neuropsychiatric status and WMH have been found in AD and frontotemporal dementia15. When considering the subgroups in the analysis, we observed interesting relationships between cognitive measures and WMH. Namely, given the relatively low variability of MMSE and CDR sum-of-box scores within the CN group, we did not observe significant associations between WMH volumes and MMSE and CDR sum-of-box scores within the CN group. However, the association between WMH burden and all three cognitive measures was significant within the EOAD group. Interestingly, while there was more variability in the scores of EOnonAD participants on MMSE, CDR sum-of-box scores, and MoCA assessments, we found no significant associations between WMH burden and cognitive test scores in EOnonAD. More investigation using larger samples will be needed to understand if higher WMH will associate with declining cognitive performance in EOnonAD. In addition, longitudinal data will elucidate potential differences in trajectories of associations over time. Given that the EOnonAD group was milder in disease severity as measured by global CDR, further analyses may consider controlling for the effect of global cognitive performance when comparing WMH between groups.

Increased WMH burden was associated with higher cerebral amyloid and tau PET uptake when considering the overall population of participants in the study. This finding is consistent with findings from pathology suggesting that WMH may result not only from ischemia related to small vessel disease, but also from cortical AD pathology16. However, once diagnostic group was included in the model to control for potential confounding by diagnosis, there was no significant association between amyloid burden and WMH volumes. Separate group specific analyses data from EOAD group in the first model and EOnonAD group in the second model further showed no association between higher WMH loads and amyloid burden.

When considering tau accumulation, while the WMH volumes in parietal and frontal areas were found to be associated with lobar cerebral microbleeds and amyloid burden6, no associations between WMH topographical patterns and tau burden either with voxel-based or region-specific analyses were identified. This may be due to the sample characteristics which consisted of a population-based sample who were primarily cognitively normal. On the contrary, WMH volumes were shown to increase with changes in cerebrospinal fluid tau levels2. Differences of WM lesions between individuals with AD related dementias and elderly non-demented participants were considered16. As opposed to non-demented elderly, WM lesions in people with AD were associated with both axonal loss and demyelination16. While no direct pathological relationship between amyloid and tau burden with decreased axonal density were identified, WMH were associated with increased hyperphosphorylated tau pathology and not small vessel disease16 which are in line with the findings of this study. Our findings on associations between tau burden from PET and WMH volumes lend support to this previous work. Future work will be needed to investigate the broad range of mechanisms that may contribute to these observed white matter changes including impaired perivascular clearance, hypoperfusion, Wallerian degeneration due to cortical neuronal/axonal loss. Further work should investigate whether the associations between tau burden and WMH are a reflection of disease duration (i.e. onset of amyloidosis). Greater tau burden indicates longer time since disease onset, hence greater damage to the vessels due to CAA. In the meantime, the absence of association with amyloid burden can likely be explained by the sigmoid shape of amyloid accumulation and the lack of range of amyloid as the disease severity progresses17. Hence, further analyses are needed to investigate whether tau burden is associated with WMH after controlling for the effect of disease onset.

Conclusions

Our finding that greater WMH burden was associated with worse cognitive performance and greater tau burden in EOAD is an important one. We show novel strong evidence that WMHs may be associated with AD pathology, independent of age-associated vascular disease and other non-AD pathology. While CAA may be a main basis of WMHs in AD, nevertheless, our findings indicate that these are correlated with increasing burden of AD. These findings shed light on the importance of considering white matter changes while assessing the disease related damage due to AD. Future work is warranted to investigate how these white matter changes may play a mechanistic role in disease progression and clinical prognosis. An interesting future research direction is comparing WMH loads and their longitudinal trajectories with those of LOAD.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

This study represents a comprehensive characterization of WMHs in sporadic EOAD.

WMH volumes are associated with tau burden from PET in EOAD suggesting WMH are correlated with increasing burden of AD.

Greater WMH volumes are associated with worse performance on global cognitive tests.

EOAD participants have higher WMH volumes compared with CN and EOnonAD groups across all brain regions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the LEADS participants and sites for their contribution to this research, as well as NACC and NCRAD.

Funding

This study is generously supported by R56 AG057195, U01AG6057195, U24AG021886, Alzheimer's Association LEADS GENETICS-19-639372, Alzheimer’s Association LDRFP-21-818464, Alzheimer’s Association LDRFP-21-824473 and Alzheimer’s Association LDRFP-21-828356. NACC is funded by the NIA (U24 AG072122). NACC data are contributed by the following NIA-funded ADRCs: P30 AG010133, P30 AG062422, P30 AG066462, P30AG066507, P30 AG062421, P30 AG066506, P30AG072977, P30 AG066444, P30 AG066515, P30 AG062677, P30 AG072980, P30 AG072979, P30 AG066511.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Ani Eloyan has no conflicts to report.

Maryanne Thangarajah has no conflicts to report.

Na An has no conflicts to report.

Bret J. Borowski has no conflicts to report.

Ashritha L. Reddy has no conflicts to report.

Paul Aisen has no conflicts to report.

Jeffrey L. Dage is an inventor on patents or patent applications of Eli Lilly and Company relating to the assays, methods, reagents and / or compositions of matter related to measurement of P-tau217. Dr. Dage has served as a consultant for Abbvie, Genotix Biotechnologies Inc, Gates Ventures, Karuna Therapeutics, AlzPath Inc, Cognito Therapeutics, Inc., and received research support from ADx Neurosciences, Fujirebio, AlzPath Inc, Roche Diagnostics and Eli Lilly and Company in the past two years. Dr. Dage is serving on a scientific advisory board for Eisai. Dr. Dage has received speaker fees from Eli Lilly and Company.

Tatiana Foroud has no conflicts to report.

Bernardino Ghetti has no conflicts to report.

Percy Griffin has no conflicts to report.

Dustin Hammers has no conflicts to report.

Leonardo Iaccarino is currently a full-time employee of Eli Lilly and Company / Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and a minor shareholder of Eli Lilly and Company. His contribution to the work presented in this manuscript was performed while he was affiliated with the University of California San Francisco

Clifford R. Jack Jr. has no conflicts to report.

Kala Kirby has no conflicts to report.

Joel Kramer has no conflicts to report.

Robert Koeppe has no conflicts to report.

Walter A. Kukull has no conflicts to report.

Renaud La Joie has no conflicts to report.

Nidhi S Mundada has no conflicts to report.

Melissa E. Murray has no conflicts to report.

Kelly Nudelman has no conflicts to report.

Malia Rumbaugh has no conflicts to report.

David N. Soleimani-Meigooni has no conflicts to report.

Arthur Toga has no conflicts to report.

Alexandra Touroutoglou has no conflicts to report.

Alireza Atri has no conflicts to report.

Gregory S. Day has no conflicts to report.

Ranjan Duara has no conflicts to report.

Neill R. Graff-Radford has no conflicts to report.

Lawrence S. Honig has no conflicts to report.

David T. Jones has no conflicts to report.

Joseph Masdeu has no conflicts to report.

Mario F. Mendez has no conflicts to report.

Erik Musiek has no conflicts to report.

Chiadi U. Onyike has no conflicts to report.

Emily Rogalski has no conflicts to report.

Steven Salloway has no conflicts to report.

Sharon Sha has no conflicts to report.

Raymond S. Turner has no conflicts to report.

Thomas S. Wingo has no conflicts to report.

David A. Wolk has served as a paid consultant to Eli Lilly, GE Healthcare, and Qynapse. He serves on a DSMB for Functional Neuromodulation. He is a site investigator for a clinical trial sponsored by Biogen.

Kyle Womack has no conflicts to report.

Laurel Beckett has no conflicts to report.

Sujuan Gao has no conflicts to report.

Maria C. Carrillo has no conflicts to report.

Gil Rabinovici has no conflicts to report.

Liana G. Apostolova has no conflicts to report.

Brad Dickerson has no conflicts to report.

Prashanthi Vemuri has no conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Yoshita M, Fletcher E, Harvey D, Ortega M, Martinez O, Mungas DM, Reed BR, and DeCarli C. Extent and distribution of white matter hyperintensities in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology. 2006;67(12):2192–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S, Viqar F, Zimmerman ME, Narkhede A, Tosto G, Benzinger TL, Marcus DS, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, et al. White matter hyperintensities are a core feature of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from the dominantly inherited Alzheimer network. Annals of neurology. 2016;79(6):929–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, and Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69(24):2197–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoemaker D, Zanon Zotin MC, Chen K, Igwe KC, Vila-Castelar C, Martinez J, Baena A, Fox-Fuller JT, Lopera F, Reiman EM, et al. White matter hyperintensities are a prominent feature of autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease that emerge prior to dementia. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2022;14(1):1–11, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S, Zimmerman ME, Narkhede A, Nasrabady SE, Tosto G, Meier IB, Benzinger TL, Marcus DS, Fagan AM, Fox NC, et al. White matter hyperintensities and the mediating role of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in dominantly-inherited Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0195838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graff-Radford J, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Knopman DS, Schwarz CG, Brown RD Jr, Rabinstein AA, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Przybelski SA, Lesnick T, et al. White matter hyperintensities: relationship to amyloid and tau burden. Brain. 2019;142(8):2483–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laing KK, Simoes S, Baena-Caldas GP, Lao PJ, Kothiya M, Igwe KC, Chesebro AG, Houck AL, Pedraza L, Hernandez AI, et al. Cerebrovascular disease promotes tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Communications. 2020;2(2):fcaa132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopkins RO, Beck CJ, Burnett DL, Weaver LK, Victoroff J, and Bigler ED. Prevalence of white matter hyperintensities in a young healthy population. Journal of Neuroimaging. 2006;16(3):243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao C, Li J, Huang X, Dong L, Liu C, Peng B, Cui L, and Gao J. White matter hyperintensities and patterns of atrophy in early onset Alzheimer’s disease with causative gene mutations. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 2021;203:106552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apostolova LG, Aisen P, Eloyan A, Fagan A, Fargo KN, Foroud T, Gatsonis C, Grinberg LT, Jack CR Jr, Kramer J, et al. The longitudinal early-onset Alzheimer’s disease study (LEADS): Framework and methodology. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2021;17(12):2043–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raghavan S, Reid RI, Przybelski SA, Lesnick TG, Graff-Radford J, Schwarz CG, Knopman DS, Mielke MM, Machulda MM, Petersen RC, et al. Diffusion models reveal white matter microstructural changes with ageing, pathology and cognition. Brain communications. 2021;3(2):fcab106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wardlaw JM, Chappell FM, Hernández MDCV, Makin SD, Staals J, Shuler K, … & M.S. White matter hyperintensity reduction and outcomes after minor stroke. Neurology. 2017;89(10), 1003–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaubert M, Lange C, Garnier-Crussard A, Köbe T, Bougacha S, Gonneaud J, … & Wirth M. Topographic patterns of white matter hyperintensities are associated with multimodal neuroimaging biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2021;13(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu HY, Ou YN, Shen XN, Qu Y, Ma YH, Wang ZT, Dong Q, Tan L, and Yu JT, White matter hyperintensities and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 prospective studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021;120:16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desmarais P, Gao AF, Lanctôt K, Rogaeva E, Ramirez J, Herrmann N,… & Masellis M. White matter hyperintensities in autopsy-confirmed frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2021;13(1), 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAleese KE, Walker L, Graham S, Moya EL, Johnson M, Erskine D, … & Attems J. Parietal white matter lesions in Alzheimer’s disease are associated with cortical neurodegenerative pathology, but not with small vessel disease. Acta neuropathologica. 2017;134(3), 459–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caroli A and Frisoni GB. Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative the dynamics of Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative cohort. Neurobiol. Aging. 2010;31, 1263–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.