Abstract

The role that collectin (mannose-binding protein) may play in the host’s defense against chlamydial infection was investigated. Recombinant human mannose-binding protein was used in the inhibition of cell culture infection by Chlamydia trachomatis (C/TW-3/OT, E/UW-5/Cx, and L2/434/Bu), Chlamydia pneumoniae (AR-39), and Chlamydia psittaci (6BC). Mannose-binding protein (MBP) inhibited infection of all chlamydial strains by at least 50% at 0.098 μg/ml for TW-3 and UW-5, and at 6.25 μg/ml for 434, AR-39, and 6BC. The ability of MBP to inhibit infection with strain L2 was not affected by supplementation with complement or addition of an L2-specific neutralizing monoclonal antibody. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and dot blot analyses showed MBP bound to the surface of the organism to exert inhibition, which appeared to block the attachment of radiolabeled organisms to HeLa cells. Immunoblotting and affinity chromatography indicated that MBP binds to the 40-kDa glycoprotein (the major outer membrane protein) on the outer surface of the chlamydial elementary body. Hapten inhibition assays with monosaccharides and defined oligosaccharides showed that the inhibitory effects of MBP were abrogated by mannose or high-mannose type oligomannose-oligosaccharide. The latter carbohydrate is the ligand of the 40-kDa glycoprotein of C. trachomatis L2, which is known to mediate attachment, suggesting that the MBP binds to high mannose moieties on the surface of chlamydial organisms. These results suggest that MBP plays a role in first-line host defense against chlamydial infection in humans.

Chlamydia is an obligate intracellular bacterium that infects mammalian and avian species. The species Chlamydia trachomatis is a major cause of ocular and genital infection in humans. Pathogenic microorganisms may use carbohydrates or carbohydrate-binding proteins to attach to or enter host cells (44). We have identified three glycoproteins in C. trachomatis with molecular weights of 40,000 (40K), 32K, and 18K (35–37) and determined that the 40-kDa glycoprotein is the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) (36). Attachment of C. trachomatis to HeLa cells appears to be mediated via the glycans that decorate the 40-kDa and the 32-kDa outer surface glycoproteins (38, 39). However, only the exogenously added glycan of the 40-kDa MOMP glycoprotein inhibited the infectivity of C. trachomatis to HeLa cells. The presence of mannose has been detected in all three glycoproteins, in addition to galactose, N-acetyl glucosamine, and fucose (36, 37). We have recently elucidated the carbohydrate structure of the C. trachomatis L2 strain by two-dimensional sugar mapping technique, showing that the major oligosaccharide component (>80%) of the 40-kDa MOMP glycoprotein was the high-mannose type oligomannose-oligosaccharide (20). Functional analysis, with structurally defined oligosaccharides, revealed that the oligomannose-oligosaccharides were the ligands mediating attachment and infectivity of C. trachomatis to HeLa cells.

Mannose-binding protein (MBP) is a collectin with collagen tails and lectin domains (5, 6). It is a mammalian C-type lectin that is synthesized by hepatocytes and secreted into circulating serum at low levels (8). Its production increases in response to stress, like trauma, surgery, and infection (33, 42). MBP appears to be a pattern recognition molecule that plays a role in first-line host defense. MBP may be considered an “ante-antibody” (7). MBP recognizes a wide range of microorganisms (6). MBP is also known to activate both the classical (11, 13, 22) and alternate complement pathways (30). The three-dimensional structure of the MBP carbohydrate recognition domain bound to a ligand reveals that the oligosaccharide binds to a calcium site and that the calcium ion binds to the equatorial 3-OH and 4-OH of the terminal mannose (43). Classical complement pathway activation can occur in the absence of antibody. This lectin pathway utilizes two novel serine proteases, mannose-binding protein-associated protease I (26) and II (40a). Alternatively, MBP may act directly as an opsonin for phagocytosis of bacteria by macrophages (15).

Because surface-exposed glycoproteins of C. trachomatis are rich in mannose and involved in infectivity (20), we examined whether infection of HeLa cells by C. trachomatis and other chlamydial species is inhibited by human MBP (hMBP) and analyzed its inhibitory mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chlamydial organisms.

C. trachomatis C/TW-3/OT, E/UW-5/Cx, and L2/434/Bu, Chlamydia pneumoniae AR-39, and Chlamydia psittaci 6BC were used. TW-3, UW-5, and 434 were grown in HeLa 229 cells (17). AR-39 and 6BC were grown in HL cells (18). All organisms were purified by density gradient centrifugation using Hypaque (Hypaque-76; Sanofi Winthrop Pharmaceuticals, New York, N.Y.) (16). The preparations contained at least 108 inclusion-forming units per ml of elementary bodies (EBs).

Human MBP.

Recombinant hMBP (rhMBP) was produced from a Chinese hamster’s ovary cells transfected with the cloned hMBP gene as previously described (15). Recombinant protein was purified from the culture supernatant by elution in a mannan-Sepharose affinity column with 50 mM mannose in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) plus 10 mM CaCl2.

Carbohydrates.

Glycopeptides containing high-mannose type and hybrid type carbohydrates from ovalbumin were prepared by fractionation with a concanavalin A-Sepharose column (Pharmacia AB, Uppsala, Sweden) according to Krusius et al. (14). Structurally defined oligomannose-oligosaccharides containing 6, 8, or 9 mannose residues and a conserved trimannosyl core were obtained from Oxford GlycoSystems, Rosedale, N.Y. These oligosaccharides are analogs to those found in the C. trachomatis L2 strain (20). Oligomannose 8,D1D3 has shown the highest activity in infectivity neutralization assays, while the trimannosyl core has shown the least activity (20). Monosaccharides, d-mannose and d-fructose, were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.

Antibodies.

Monoclonal antibodies used were anti-rhMBP (31), anti-C. trachomatis MOMP, which is specific against L2 serovar (155-35), anti-C. trachomatis MOMP, which is species-specific (KK-12), and antichlamydial lipopolysaccharide, which is genus-specific (CF-2). 155-35 is a neutralizing antibody, while KK-12 and CF-2 are nonneutralizing, all of which have been described (23, 38). Rabbit antisera, anti-C. trachomatis L2 (3), and anti-C. pneumoniae AR-39 (4) were prepared by immunization of animals with whole EB antigens.

Inhibition of cell culture infection by chlamydial organisms with mannose-binding protein.

Assays of inhibition of cell culture infectivity by MBP were performed by using HeLa 229 (TW-3, UW-5, and 434) or HL (AR-39 and 6BC) cell monolayers grown in 96-well microtiter plates (2). MBP was diluted in a fourfold series in a 96-well plate so that the final volume in each well for each dilution contained 90 μl. An equal volume of 2 × 104 inclusion forming units/ml of organism suspension was added to each well. The range of MBP concentrations tested was 100 to 0.0245 μg/ml. The plate was rocked gently for 30 min at 35°C. Fifty microliters of each MBP/organism mixture was absorbed onto previously prepared cell monolayers in duplicate for 2 h at 35°C on a rocker platform. The inocula were removed, the monolayers were washed with modified Hanks balanced salt solution, pH 8.0, containing 2 mM calcium without glucose and phenol red indicator, and culture medium was added to each well. The 96-well plate was sealed with parafilm and incubated for 72 h at 35°C. Then the medium was removed, and the wells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were fixed with methanol and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal antibody CF-2 for inclusion counts. The percentage of inhibition was determined by comparing inclusion counts of the wells containing MBP to those without MBP. The endpoints were defined as the minimum concentrations of MBP to produce inhibition of greater than 50% (2). High-mannose type glycopeptides and hybrid type glycopeptides were included as positive and negative controls, respectively, for inhibition assays. When complement was tested, guinea pig complement was used at a final dilution of 1:500. This dilution had been predetermined to be effective in antibody neutralization. In testing the experiments as to whether there was an additive effect of MBP and antibody, monoclonal antibody 155-35 at a single dilution of 10−3 was used.

Tests for calcium dependency of MBP.

Two methods were used to test for calcium dependency of MBP: omission of 2 mM CaCl2 from the buffer or chelation of CaCl2 with 2 mM EDTA.

Hapten inhibition.

MBP was preincubated with d-mannose or d-fructose (100 and 10 mM) for 1 h at room temperature before reacting with organisms in the infectivity assay or applying to nitrocellulose paper or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates in binding assays. Alternatively, for hapten inhibition studies with defined oligosaccharides, carbohydrates were added to the antigen after the blocking step and incubated for 1 h. Subsequently, MBP was added, and the same protocol as stated below was followed for immunoblotting or ELISA. Oligosaccharides were tested at 200, 50, 12.5, and 3.1 ng/well concentrations.

Radiolabeling of chlamydial organisms.

Chlamydial organisms were metabolically labeled by culturing with low leucine (1/10 of the normal concentration)-Eagle’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 50 μCi of [3H]leucine (specific activity, 180 Ci/mmol; Du Pont NEN, Boston, Mass.) per 112-cm2 flask in the presence of 0.8 μg of cycloheximide per ml (16). Tritium-labeled organisms were purified by centrifugation through a cushion of 30% Hypaque-76 and resuspended in TBS.

Inhibition of attachment of tritiated chlamydial organisms to HeLa cells by mannose-binding protein.

The assay for inhibition of attachment of tritiated chlamydial organisms to HeLa cell monolayers was carried out in culture vials as described previously (16). MBP was tested at 100, 25, and 6.25 μg/ml concentrations in TBS containing 2 mM CaCl2. Organisms were incubated with MBP at room temperature for 30 min. MBP/organism mixtures were inoculated onto HeLa cell monolayers in duplicate and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Inocula were removed and cell monolayers were washed three times with TBS. One milliliter of tissue solubilizer (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) was added per vial and incubated at room temperature overnight. Digested tissue suspension was dissolved in 10 ml of scintillation fluid (Amersham), and the radioactivity was counted in a scintillation counter (LS-5800 series, Liquid Scintillation System; Beckman Instruments, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). MBP-treated organisms were compared to organisms only. Controls used were high-mannose type and hybrid type glycopeptide from ovalbumin as the positive and negative inhibitor, respectively (20).

Assay of binding MBP to whole chlamydial organisms.

Two methods were used for assaying binding of MBP to chlamydial organisms: (i) ELISA and (ii) dot blot.

(i) ELISA.

The wells of a 96-well microtiter plate were precoated by applying 50 μl of EB (50 μg/ml) in modified Hanks balanced salt solution to each well and incubated overnight. The plate was then blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at 37°C in TBS (0.05 M Tris-HCl, 0.15 M NaCl [pH 7.2]). Fifty microliters of MBP at 200 ng/ml diluted in the same solution with 50 mM CaCl2 was added to the wells. The plate was incubated for 3 h at 37°C. After washing, the anti-rhMBP (1:1,000 dilution) was added and incubated for 2 h. The wells were washed and incubated with goat anti-mouse antiserum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 2 h. After washing, 100 μl of substrate (ABTS Microwell Peroxidase Substrate System; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) was added to each well. The plate was read at 405 nm on a Thermomax microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, Calif.). Slightly different conditions were used for hapten inhibition: 0.05% Tween 20 was used for blocking, and MBP was absorbed at room temperature overnight.

(ii) Dot blot.

Five microliters of EB suspensions was applied onto nitrocellulose papers and air dried overnight. The nitrocellulose papers were blocked with 1% BSA in TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 for 1 h and incubated with MBP at 200 μg/ml for 3 h. After washing, the anti-rhMBP (1:1,000 dilution) was added and reacted for 2 h. The nitrocellulose papers were washed and incubated with goat anti-mouse antiserum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 2 h. After washing, the reaction was revealed by adding 4-chloro-1-naphthol as substrate.

Determination of chlamydial proteins that bind to mannose-binding protein. (i) Immunoblotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by immunoblotting was used to identify specific chlamydial proteins that bound to MBP. Nitrocellulose paper containing chlamydial proteins was blocked with 1% BSA in TBS for 1 h at 37°C and washed in TBS with 0.05% Tween 20. TBS in Tween 20 containing 50 mM CaCl2 was used as the diluent in the remaining steps. Blots were incubated with MBP overnight at room temperature. The nitrocellulose strips were washed and reacted with anti-rhMBP overnight. After washing, goat anti-mouse anti-serum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was incubated with the proteins for 2 h. TBS alone was used in the final washings. The protein bands were visualized with 4-chloro-1-naphthol as substrate.

(ii) Affinity chromatography.

EBs were solubilized in TBS with 25 mM n-octyl β-d-glucopyranoside for 1.5 h at 35°C, then dialyzed overnight. Following the manufacturer’s protocol (Pierce Co., Rockford, Ill.), solubilized EBs were subjected to mannan-binding protein affinity chromatography. The column was prepared by washing it at room temperature with TBS containing 2 mM EDTA and then equilibrated at 4°C with TBS containing 2 mM CaCl2. A 1-ml sample of solubilized EBs diluted 1:1 in TBS containing CaCl2 was applied to the mannan-binding protein column and then incubated at 4°C for 30 min. After the column was washed with TBS, bound glycoproteins were eluted with TBS without CaCl2 and with 10 mM EDTA at room temperature. The fractions containing eluant were pooled and concentrated in a Millipore Ultrafree-CL filter (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.). The glycoproteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Coomassie blue staining of gels and immunoblotting following electrotransfer of separated proteins to nitrocellulose paper.

RESULTS

Inhibition of infectivity with MBP.

Inhibitory effects of MBP on infection of cell cultures by chlamydial strains were examined. As shown in Table 1, all chlamydial strains tested were susceptible to inhibition by MBP. Differences in susceptibility among chlamydial strains were observed. The trachoma biovar of C. trachomatis was more sensitive than the lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) biovar of C. trachomatis, C. pneumoniae, and C. psittaci, with endpoints of 0.098 μg/ml versus 6.25 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of cell culture infection by Chlamydia spp. with rhMBP

| Strains | MIC50 of rhMBPa (μg/ml) |

|---|---|

| C. trachomatis | |

| C/TW-3/OT | 0.098 |

| E/UW-5/Cx | 0.098 |

| L2/434/Bu | 6.25 |

| C. pneumoniae | |

| AR-39 | 6.25 |

| C. psittaci | |

| 6BC | 6.25 |

Repeated tests gave identical endpoints.

The L2 strain of C. trachomatis was then used to test other parameters of inhibition. MBP was tested at a single dilution of 6.25 μg/ml. The hapten inhibition assay showed that the inhibitory effect of MBP was annulled by preincubation of MBP with 100 mM mannose but not with 100 mM fructose. Inhibition of infectivity by MBP was 39% with organisms preincubated with mannose, compared to 67% with untreated organisms. Organisms treated with 100 mM fructose yielded 68% inhibition, which was similar to untreated organisms. As expected, calcium depletion also abolished the inhibitory effect of MBP on infectivity. Inhibition of infectivity by MBP was only 29% without calcium versus 67% with calcium.

Supplementation with complement produced only a single fourfold dilution difference in the endpoint. The inhibitory concentration of MBP was 1.56 μg/ml in the presence of complement, compared to 6.25 μg/ml in the absence of complement. However, this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Whether MBP would augment complement-dependent antibody neutralization of infectivity was also examined. The same protocol with and without complement was followed. MBP at an inhibitory concentration of 6.25 μg/ml did not enhance antibody neutralization of infectivity. The average percent inhibition of two experiments in the absence of complement was 32% for antibody alone, 62% for MBP alone, and 65% for antibody plus MBP. When complement was added the percent inhibition was 64, 73, and 81%, respectively.

Inhibition of attachment of chlamydial organisms to HeLa cells with MBP.

Whether MBP inhibits the attachment of organisms to HeLa cells was examined. The inhibition assays were performed using tritium-labeled organisms. As shown in Table 2, attachment of chlamydial EBs to HeLa cells was inhibited by greater than 50% by MBP at 100 and 25 μg/ml. These results suggest that MBP inhibits infectivity by inhibiting attachment of organisms to the host cell surface.

TABLE 2.

Inhibition of attachment of Chlamydia trachomatis L2/434/Bu organisms to HeLa cells with rhMBP

| Concentration of rhMBP (μg/ml) | % Inhibitiona (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| 100 | 76 ± 2.5 |

| 25 | 53 ± 1.0 |

| 6.25 | 20 ± 3.0 |

Average of two experiments, with each experiment performed in duplicate; radioactivity counts in the control tubes inoculated with organisms not treated with rhMBP were 1,200 and 1,500 cpm/tube in each experiment.

Binding of MBP to whole chlamydial organisms.

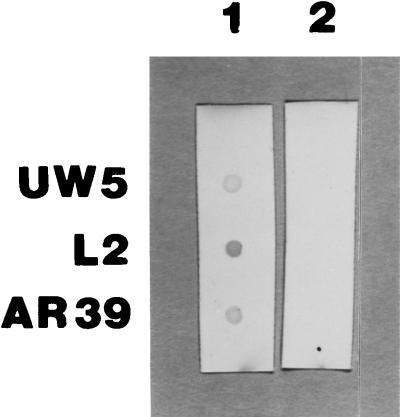

Whether MBP binds to the surface of chlamydial organisms to exert inhibition was determined by ELISA (Table 3) and dot blot (Fig. 1) by using UW-5, L2, and AR-39 strains. Both tests showed that MBP bound to the surface of organisms.

TABLE 3.

ELISA of binding of MBP to the chlamydial elementary body

| Strainsa | MBPb | OD (mean ± SD)c |

|---|---|---|

| 434 | + | 0.782 ± 0.029 |

| − | 0.169 ± 0.068 | |

| UW-5 | + | 0.786 ± 0.025 |

| − | 0.187 ± 0.078 | |

| AR-39 | + | 0.845 ± 0.125 |

| − | 0.184 ± 0.079 |

434, C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu; UW-5, C. trachomatis E/UW-5/Cx; AR-39, C. pneumoniae.

Three-hour absorption of MBP to EB; + indicates presence of all ELISA reactants, − indicates presence of all ELISA reactants except MBP; optical densities (ODs) of EBs only were 0.053 to 0.054.

Mean ± standard deviation of four experiments of duplicate wells; P < 0.001 between MBP + and − for all strains.

FIG. 1.

Photo of dot blot analysis of binding of rhMBP to whole chlamydial organisms. Purified chlamydial organisms were dotted onto nitrocellulose papers and air dried overnight. The nitrocellulose papers were blocked with 1% BSA for 1 h and incubated with rhMBP for 3 h. Binding of MBP was detected by reacting the nitrocellulose papers with anti-MBP for 2 h, followed by incubating goat anti-mouse antiserum conjugated to peroxidase for 2 h. The reaction was revealed by addition of 4-chloro-1-naphthol as substrate. Lane 1 shows positive reactions, and lane 2 shows negative reactions in which MBP was omitted. Negative reactions in which only anti-MBP was omitted are not shown. UW-5, C. trachomatis E/UW-5/Cx; L2, C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu; AR-39, C. pneumoniae. MBP bound to all three strains tested.

Identification of chlamydial proteins that bind to MBP.

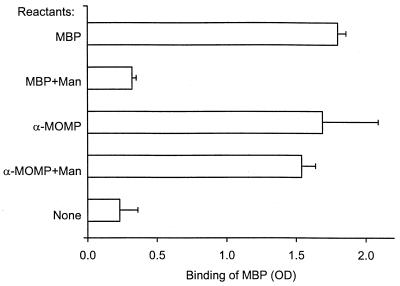

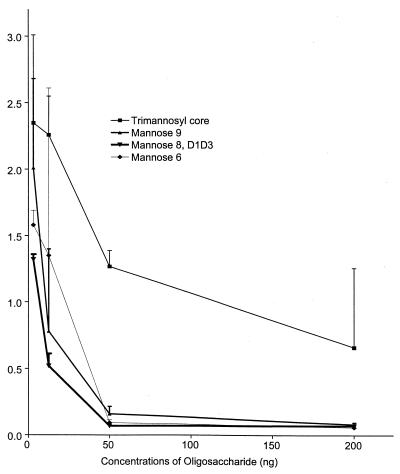

Three different methods were used to determine that the chlamydial protein that binds to MBP was the MOMP. First, a hapten inhibition assay was conducted to see whether MBP binds to mannose on the glycoprotein of the bacterial cell surface. The results showed that the binding of MBP to EB was inhibited effectively by mannose (Fig. 2). Oligomannose-oligosaccharides found in the 40-kDa MOMP glycoprotein also inhibited the binding of MBP to EB (Fig. 3). Nearly complete inhibition was observed at concentrations of 50 ng or greater. As previously seen in inhibition of infectivity (20), mannose-8,D1D3 was the most effective oligosaccharide tested. Binding of anti-MOMP monoclonal antibody KK-12 to EB was not inhibited by mannose (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Graph of hapten inhibition of binding of rhMBP to whole chlamydial organisms with mannose (Man) by ELISA. MBP was preincubated with 100 mM mannose for 1 h at room temperature. rhMBP (10 ng) was added to the wells of a microtiter plate precoated with whole organisms (EB) of C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu and incubated overnight. The plate was washed and incubated overnight with anti-hMBP monoclonal antibody followed by goat anti-mouse antiserum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The plate was read at 405 nm after 4-chloro-1-naphthol was added as substrate. Controls consisted of binding of anti-40-kDa MOMP monoclonal antibody KK-12 (α-MOMP) and no MBP (none). α-MOMP was reacted overnight with organisms followed by conjugate and substrate, as with binding of MBP, except no MBP was added. Each bar is the average of the OD reading of two experiments.

FIG. 3.

Graph of inhibition of binding of rhMBP to chlamydial organisms with oligosaccharides by ELISA. Fourfold dilutions of oligosaccharides were incubated for 1 h in wells of a microtiter plate precoated with whole organisms (EB) of C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu. rhMBP (10 ng) was then added to the wells and reacted overnight. After washing, anti-rhMBP monoclonal antibody was incubated overnight in the wells followed by goat anti-mouse antiserum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and substrate. The plate was read at 405 nm. Each point is the average of the OD reading of two experiments. Oligosaccharides tested were oligomannose-oligosaccharides containing 6, 8, or 9 mannose residues and a conserved trimannosyl core. Controls included wells incubated with rhMBP alone and with diluent alone (not shown).

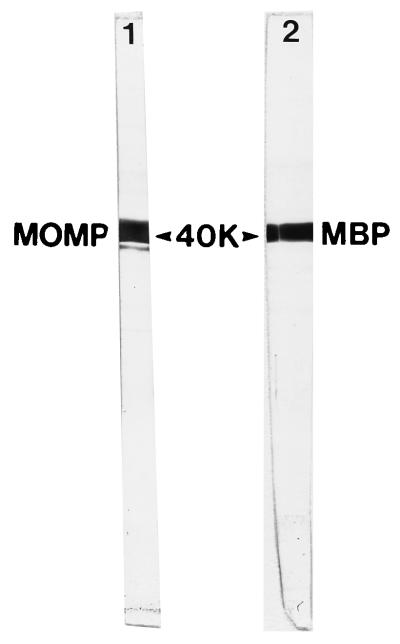

Second, immunoblotting was used to identify which chlamydial proteins bind to MBP. Immunoblotting of whole EB lysates revealed that only the 40-kDa MOMP bound consistently to MBP (Fig. 4, lane 2). The major carbohydrate components of the 40-kDa MOMP glycoprotein are the high-mannose type oligosaccharides (20).

FIG. 4.

Photo of immunoblot showing C. trachomatis proteins that bind to MBP. Whole organism lysate of C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose papers. The paper strips were reacted separately with anti-40-kDa C. trachomatis MOMP monoclonal antibody KK-12 (lane 1) or MBP (lane 2) and probed with anti-mouse antiserum conjugated to peroxidase (lane 1) and anti-mannose-binding protein antiserum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (lane 2), respectively. 4-Chloro-1-naphthol was used as substrate. Immunoblots revealed that the protein bound to MBP was the 40-kDa MOMP. Not shown are the negative reactions with controls in which only MBP or KK-12 was omitted.

Third, affinity chromatography with mannan as ligand was used to identify chlamydial proteins that bind to MBP. Whole-cell lysates of L2 and AR-37 organisms were applied onto an affinity column, and eluted proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with rabbit anti-sera to C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu and C. pneumoniae AR-39. The proteins eluted from the column were shown to be the 40-kDa proteins (data not shown), indicating the major protein involved in the interaction with MBP is the 40-kDa MOMP.

DISCUSSION

Infection of HeLa cells by chlamydiae was inhibited by MBP in the presence or absence of complement. The trachoma biovar of C. trachomatis, the least invasive strain among the three chlamydial species tested, was most susceptible to inhibition by MBP, i.e., 0.08 μg/ml versus 6.25 μg/ml. Analysis of inhibitory mechanisms using radiolabeled organisms revealed that MBP blocked the attachment of chlamydia to HeLa cells. It appears that MBP binds to the 40-kDa MOMP glycoprotein located on the outer surface of EBs, thus impeding entry of the organism into the host cell and subsequent infection. Hapten inhibition analysis indicated that mannose or oligomannose-oligosaccharides associated with the previously identified and characterized 40-kDa MOMP glycoprotein of C. trachomatis L2 (20) play a role in this phenomenon.

The MBP is a pattern recognition molecule that appears to play a role in first-line host defense against bacteria, yeast, viruses, and protozoans rich in mannose (9, 12, 15, 29, 30, 33). MBP has also been detected in human amniotic fluid (24) and secretions of the upper respiratory tract, i.e., secretions of the nasopharynx and effusions of the middle ear in children (10). Interestingly, antimicrobial activity of amniotic fluid against C. trachomatis has been reported (41). The MIC at which 50% of the isolates are inhibited (MIC50) for the trachoma biovar of C. trachomatis is within the range of the normal concentrations of MBP in amniotic fluids (0.304 μg/ml [0.084 to 0.64 μg/ml] at 32 weeks of gestation and 1 μg/ml [0.048 to 2.282 μg/ml] at 35 weeks of gestation) (24). Therefore, it seems imperative to study how MBP in these body fluids affects the outcome of infection of fetuses and newborns by mothers having cervical C. trachomatis infection, since maternal infection often results in fetal death or premature birth (25) and infantile pneumonia (1).

MBP may also work in the line of defense against hematogenous dissemination of chlamydia in humans. Systemic disease is common in C. psittaci infection in animals, especially in avians, but not in non-LGV serovars of C. trachomatis. Recent studies suggest that C. pneumoniae spreads systemically via infected macrophages in humans and animals. In humans, C. pneumoniae has been detected in cervical lymph nodes, spleen, and liver. A few case studies showed severe systemic manifestation (19). The detection of C. pneumoniae in 50% of atheromatous plaques of major arteries has presented the strongest evidence for systemic disease caused by C. pneumoniae (19). In mice, C. pneumoniae has been shown to disseminate readily from lungs following intranasal inoculation to spleen and peritoneal macrophages in Swiss Webster mice (45) and to atheromatous lesions in the aorta in ApoE mice (27). When systemic infection with C. pneumoniae occurred, bacteremia was seen, but the organisms were only found intracellularly in mononuclear phagocytes (28). These are exciting findings because bacteremia has been rarely demonstrated in human chlamydial infection. When it is demonstrated, as has been observed in psittacosis, a disease contracted from C. psittaci-infected birds, the organisms are usually recovered from the buffy coat (32). The observations that systemic dissemination of chlamydia is by infected macrophages and not by free particles suggest a possible role of serum MBP in inactivating infectivity of chlamydia if the organism gets into circulation in a free form. This hypothesis is supported by the observations of this study and the fact that the normal serum levels of MBP (0.995 μg/ml [0.01 to 4.47 μg/ml] (21, 34) to 1.67 μg/ml [0.28 to 8.67 μg/ml] [10] in Caucasians and 1.645 μg/ml [1.395 to 2.065 μg/ml] [21] to 1.72 ± 1.15 μg/ml [40] in Asians), are inhibitory in vitro. The lack of observation of systemic spread of non-LGV C. trachomatis coupled to the systemic spread of C. psittaci and C. pneumoniae may be correlated with sensitivity to the MBP.

MBP effectively inhibited C. trachomatis infection of HeLa cells in the presence and absence of complement. However, MBP did not enhance the neutralization of chlamydial infectivity with antibodies. It is possible that any small inhibitory effect by MBP on chlamydial infection was masked by the large effect of complement-dependent antibody neutralization. These findings show chlamydia is another infectious agent against which MBP could play a role in host defense infection (7). Because MBP may activate complement and facilitate the phagocytosis and killing of microorganisms, further in vitro studies should be conducted with polymorphonuclear and mononuclear phagocytic cells.

In conclusion, we have shown that MBP may play a role in the first-line host defense against chlamydia. The experimental data support our previous structural and functional analyses showing the presence of a specific high-mannose type oligosaccharide linked to the 40-kDa major outer membrane protein of C. trachomatis which mediates attachment and infectivity of the organism to HeLa cells (20). We have also demonstrated that the differential sensitivity to inhibition by MBP among chlamydial strains may be correlated with the ability of chlamydial strains to disseminate systemically by the hematogenous route.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant EY00219 from the National Eye Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beem M O, Saxon E M. Respiratory-tract colonization and a distinctive pneumonia syndrome in infants infected with Chlamydia trachomatis. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:306–310. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197702102960604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne G I, Stephens R S, Ada G, Caldwell H D, Su H, Morrison R P, Van Der Pol B, Bavoil P, Bobo L, Everson S, Ho Y, Hsia R C, Kennedy K, Kuo C-C, Montgomery P C, Peterson E, Swanson A, Whitaker C, Whittum-Hudson J, Yang C L, Zhang Y-X, Zhong G M. Workshop on in vitro neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis: summary of proceedings. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:415–420. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldwell H D, Kuo C-C, Kenny G E. Antigenic analysis of chlamydiae by two-dimensional immunoelectrophoresis. I. Antigenic heterogeneity between C. trachomatis and C. psittaci. J Immunol. 1975;115:963–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell L A, Kuo C-C, Grayston J T. Structural and antigenic analysis of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1990;58:93–97. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.93-97.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drickamer K, Taylor M E. Biology of animal lectins. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:237–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein J, Eichbaum Q, Sheriff S, Ezekowitz R A B. The collectins in innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezekowitz R A B. Ante-antibody immunity. Curr Biol. 1991;1:60–62. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(91)90132-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ezekowitz R A B, Day L E, Herman G A. A human mannose-binding protein is an acute-phase reactant that shares sequence homology with other vertebrate lectins. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1034–1046. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ezekowitz R A B, Kuhlman M, Groopman J E, Byrn R A. A human serum mannose-binding protein inhibits in vitro infection by the human immunodeficiency virus. J Exp Med. 1989;169:185–196. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garred P, Brygge K, Sorensen C H, Madsen H O, Thiel S, Svejgaard A. Mannan-binding protein—levels in plasma and upper-airways secretions and frequency of genotypes in children with recurrence of otitis media. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;94:99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeda K, Sannoh T, Kawasaki N, Kawasaki T, Yamashina I. Serum lectin with known structure activates complement through the classical pathway. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7451–7454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn S J, Wleklinski M, Ezekowitz R A B, Coder D, Aruffo A, Farr A. The major surface glycoproteins of Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes are ligands of the human serum mannose-binding protein. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2649–2656. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2649-2656.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki N, Kawasaki T, Yamashina I. A serum lectin (mannan-binding protein) has complement-dependent bactericidal activity. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1989;106:483–489. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krusius T, Finne J, Rauvala H. The structural basis of the different affinities of two type of acidic N-glycosidic glycopeptides for concanavalin A-Sepharose. FEBS Lett. 1976;71:117–120. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhlman M, Joiner K, Ezekowitz R A B. The human mannose-binding protein functions as an opsonin. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1733–1745. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo C-C, Grayston J T. Interaction of Chlamydia trachomatis organisms and HeLa 229 cells. Infect Immun. 1976;13:1103–1109. doi: 10.1128/iai.13.4.1103-1109.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo C-C, Wang S-P, Grayston J T. Growth of trachoma organism in HeLa 229 cell culture. In: Hobson D, Holmes K K, editors. Nongonococcal urethritis and related infections. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1977. pp. 328–336. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo C-C, Grayston J T. A sensitive cell line, HL cells, for isolation and propagation of Chlamydia pneumoniae, strain TWAR. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:755–758. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.3.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo C-C, Jackson L A, Campbell L A, Grayston J T. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:451–461. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo C-C, Takakhashi N, Swanson A F, Ozeki Y, Hakomori S. An N-linked high-mannose type oligosaccharide, expressed at the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis, mediates attachment and infectivity of the microorganism to HeLa cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;98:2813–2818. doi: 10.1172/JCI119109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipscombe R J, Sumiya M, Hill A V S, Lau Y L, Levinsky R J, Summerfield J A, Turner M W. High frequencies in African and non-African populations of independent mutation in the mannose binding protein gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:709. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu J, Thiel S, Wiedermann H, Timple R, Reid K M. Binding of the pentamer/hexamer forms of mannan-binding protein to zymosan activates the proenzyme C1r2 C1s2 complex of the classical pathway of complement, without involvement of C1q. J Immunol. 1990;144:2287–2294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucero M E, Kuo C-C. Neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis cell culture infection by serovar-specific monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1985;50:595–597. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.595-597.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malhotra A, Willis A C, Bernal Lopez A, Thiel S, Sim R B. Mannose-binding protein levels in human amniotic fluid during gestation and its interaction with collectin receptor from amnion cells. Immunology. 1994;82:439–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin D H, Koutsky L, Eschenbach D A, Daling J R, Alexander E R, Benedetti J K, Holmes K K. Prematurity and perinatal mortality in pregnancies complicated by maternal Chlamydia trachomatis infection. JAMA. 1982;247:1585–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsushita M, Fujita T. Activation of the classical complement pathway by mannose-binding protein in association with a novel C1s-like serine protease. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1497–1502. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moazed T C, Kuo C-C, Grayston J T, Campbell L A. Murine model of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and atherosclerosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:883–890. doi: 10.1086/513986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moazed, T. C., C.-C. Kuo, J. T. Grayston, and L. A. Campbell. Evidence of systemic dissemination of Chlamydia pneumoniae via macrophages in the mouse. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Reading P C, Hartley C A, Ezekowitz R A B, Anders E M. A serum mannose-binding lectin mediates complement-dependent lysis of influenza virus-infected cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;217:1128–1136. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schweinle J E, Ezekowitz R A B, Tenner A J, Kuhlman M, Joiner K A. Human mannose-binding protein activates the alternative complement pathway and enhances serum bactericidal activity on mannose-rich isolates of Salmonella. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1821–1829. doi: 10.1172/JCI114367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schweinle J E, Nishiyasu M, Ding T Q, Sastry K, Gillies S D, Ezekowitz R A B. Truncated forms of mannose-binding protein multimerize and bind to mannose-rich Salmonella montevideo but fail to activate complement in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:364–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shapiro D S, Kenney S C, Johnson M, Davis C H, Knight S T, Wyrick P B. Chlamydia psittaci endocarditis diagnosed by blood culture. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1192–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204303261805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Summerfield J A. The role of mannose-binding protein in host defense. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:473–477. doi: 10.1042/bst0210473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Super M, Gillies S D, Foley S, Sastry K, Schweile J E, Silverman V J, Ezekowitz R A B. Distinct and overlapping functions of allelic forms of human mannose binding protein. Nat Genet. 1992;2:50–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0992-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swanson A F, Kuo C-C. Identification of lectin-binding proteins in Chlamydia species. Infect Immun. 1990;58:502–507. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.2.502-507.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swanson A F, Kuo C-C. Evidence that the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis is glycosylated. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2120–2125. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2120-2125.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swanson A F, Kuo C-C. The characterization of lectin-binding proteins of Chlamydia trachomatis as glycoproteins. Microb Pathog. 1991;10:465–473. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90112-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanson A F, Kuo C-C. Binding of the glycan of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis to HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:24–28. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.24-28.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swanson A F, Kuo C-C. The 32-kDa glycoprotein of Chlamydia trachomatis is an acidic protein that may be involved in the attachment process. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;123:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terai I, Kobayashi K, Fujita T, Hagiwara K. Human serum mannose binding protein (MBP): development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and determination of levels in serum from 1085 normal Japanese and in some body fluids. Biochem Med Metabol Biol. 1993;50:111–119. doi: 10.1006/bmmb.1993.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40a.Thiel S, Vorup-Jensen T, Stover C M, Schwaeble W, Laursen S B, Poulsen K, Willis A C, Eggleton P, Hansen S, Holmskov U, Reid K B M, Jensenius J C. A second serine protease associated with mannan-binding lectin that activates complement. Nature. 1997;386:506–510. doi: 10.1038/386506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas G B, Sbarra A J, Feingold M, Cetrulo C L, Shakr C, Newton E, Selvaraj R J. Antimicrobial activity of amniotic fluid against Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:16–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90767-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turner M W. Functional aspects of mannose-binding protein. In: Ezekowitz R A B, Sastry K, Reid K B M, editors. Collectins and innate immunity. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Publishing; 1996. pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weis W I, Drickamer K, Hendrickson W A. Structure of a C-type mannose-binding protein determined by MAD phasing. Science. 1991;254:1608–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.1721241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wick M D J, Madara J L, Fields B N, Normak S J. Molecular cross talk between epithelial cells and pathogenic microorganisms. Cell. 1991;67:651–659. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Z-P, Kuo C-C, Grayston J T. Systemic dissemination of Chlamydia pneumoniae following intranasal inoculation in mice. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:736–738. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]