Abstract

Residues beyond the first coordination shell are often observed to make considerable cumulative contributions in enzymes. Due to typically indirect perturbations of multiple physicochemical properties of the active site, however, their individual and specific roles in enzyme catalysis and disease-causing mutations remain difficult to predict and understand at the molecular level. Here we analyze the contributions of several second-shell residues in phosphate-irrepressible alkaline phosphatase of Flavobacterium (PafA), a representative system as one of the most efficient enzymes. By adopting a multi-faceted approach that integrates quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical free energy computations, molecular mechanical molecular dynamics simulations, and density functional theory cluster model calculations, we probe the rate-limiting phosphoryl transfer step and structural properties of all relevant enzyme states. In combination with available experimental data, our computational results show that mutations of the studied second-shell residues impact catalytic efficiency mainly by perturbation of the apo state and therefore substrate binding, while they do not affect the ground state or alter the nature of phosphoryl transfer transition state significantly. Several second-shell mutations also modulate the active site hydration level, which in turn influences the energetics of phosphoryl transfer. These mechanistic insights also help inform strategies that may improve the efficiency of enzyme design and engineering by going beyond the current focus on the first coordination shell.

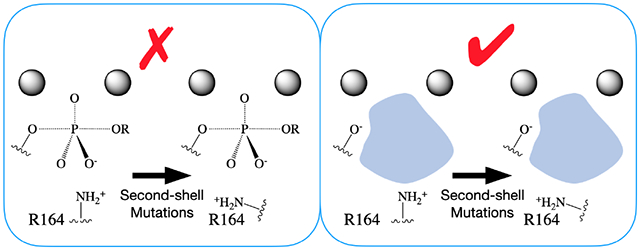

Graphical Abstarct

Introduction

Enzymes are extraordinary catalysts with remarkable catalytic efficiency and specificity.1 Extensive efforts have been focused on naturally evolved and designed enzymes to establish the physical principles and molecular features that govern their catalytic properties.2–8 One common observation is that residues beyond the first coordination shell of the substrate can often make considerable cumulative contributions to the catalytic efficiency, specificity and substrate scope.9–16 Stimulated by these observations, numerous experimental and computational studies aimed to reveal the precise molecular mechanism of the notable mutation effects of distal residues to enzyme catalysis.9,17,18 A general consideration is that due to the energetic coupling among residues in the enzyme, local changes associated with remote mutations propagate into the active site to impact conformational equilibria of key catalytic residues or electrostatics therein. For example, a combination of mutagenesis, kinetic, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) as well as computational studies of the dihydrofolate reductase supported the notion of a coupled network of interactions between residues that are spatially separated in the protein structure, leading to considerable contributions of distal residues to the hydride donor-acceptor distance distributions and therefore hydride transfer kinetics.9,19–21 Moreover, NMR and extensive molecular dynamics simulations have shown that in many cases, distal mutations lead to a redistribution of pre-existing conformational states that favor a particular catalytic activity,14,22–24 or they alter the conformational dynamics of essential structural motifs that gate the active site pocket and therefore substrate binding/product dissociation.18,25–29 Building on these mechanistic insights, considerable progress has also been made to identify the location of remote regions that might couple strongly with the active site, which may help reduce the cost of powerful yet time-consuming enzyme engineering approaches such as random saturation mutagenesis and directed evolution30,31 by providing decent starting points. Prominent examples include using chemical shift perturbations32 to locate sites that respond to binding of inhibitors, using correlation-based analysis of molecular dynamics trajectories17 to locate residues allosterically coupled to the active site, and using flexibility profiles33 to identify sites that dictate functionally relevant dynamics of enzymes.

Despite these recent progress, a thorough understanding of the roles of residues beyond the active site is often lacking. Their individual contributions are generally modest in magnitude, making it challenging to be captured by either experimental or computational approaches. Remote residues may also contribute to catalysis by indirectly perturbing multiple physicochemical properties of the active site, which are not limited to the conformational landscape of catalytic residues as extensively discussed in the literature.5,28,34 Without an in-depth mechanistic understanding by dissecting the contributions, it remains difficult to prioritize the optimization of commonly discussed active site structural and dynamical properties, such as the breadth of the conformational ensemble35,36 or (de)solvation of catalytic motifs34 by tuning residues outside the active site. This represents a significant limitation for predicting the location and identity of remote residues that have beneficial effects on the desired catalytic properties in enzyme engineering, especially when exploring new chemical transformations. Given that the current strategy is to focus mostly on the first coordination shell,37 which has been increasingly recognized to account for the relatively low activity of designed enzymes,14,22–24,28 it is therefore imperative to establish the mechanism of nonactive-site residues at the molecular level to further develop design strategies for achieving efficient catalysis. Moreover, disease-causing (e.g., drug-resistant) mutations in enzymes are often found outside of the active site,9,38,39 thus a better mechanistic understanding of their impact is also of major significance to alleviate or counter the negative effects of mutations. As an initial effort along these lines, we focus on a set of second-shell residues in a highly efficient enzyme using a comprehensive set of computational analyses.

The specific system is the phosphate-irrepressible alkaline phosphatase of Flavobacterium (PafA, Fig. 1a),40 which is one of the most efficient enzymes with a rate enhancement of 1016 over the uncatalyzed phosphate monoester hydrolysis in solution.42,43 Markin et al.40,44 have systematically explored the effects of more than 1000 Val and Gly mutations on the folding stability and catalytic activities of PafA. While the largest impact was from mutations of first-shell residues (Fig. 1b), it was observed that many second-shell residues and beyond make considerable contributions to catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km), substrate specificity (the ratio of phosphate monoester and diester activities), product inhibition (inorganic phosphate binding) and the binding affinity of the transition state analogs.44 For example, mutations of residues outside the active site were observed to cause a notable degree of decrease in kcat/Km for methyl phosphate monoester (MeP) hydrolysis, highlighting that the extraordinary catalytic efficiency of PafA is not merely determined by the bi-metallic core and the first-shell residues. The availability of the systematic kinetics data set, together with ample structural and biochemical information of PafA41,42 makes it an ideal system for better elucidating the roles of residues beyond the first coordination shell in enzymes.

Figure 1: Overview of PafA active site and the catalytic cycle.

(a) The positions of the substrate, the deprotonated nucleophile T79, two catalytic Zn2+ ions, first-shell residues (shown in CPK), and some second-shell residues (shown in licorice) whose mutations were observed to reduce kcat/Km substantially in the recent experimental study.40 Hydrogen atoms are not shown for clarity. (b) The active site schematics for the phosphoryl transfer transition state for the monoester substrate and the first-shell residues that stabilize the non-bridging oxygens. Adapted with permission from Ref. 41. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. (c) The catalytic cycle for the phosphate ester hydrolysis. E: the enzyme; ROP: the phosphate monoester substrate; E·ROP: the Michealis complex (the ground state); RO−: the leaving group; E-P: the covalent phospho-threonine intermediate; HO−: hydroxide ion; E·Pi: the enzyme complex with the inorganic phosphate, Pi.

We focus here on several second-shell residues, A302, Y112 and D163, which are in direct contact with the first coordination shell of O2 of the MeP substrate in PafA (K162 and R164, see Fig. 1a); to evaluate non-additivity of second-shell contributions, a double mutant involving both Y112 and D163 is also studied. The choice of this set of residues is motivated by the following considerations. First, they make considerable contributions to the catalytic efficiency with typical fold changes of 10–30 on kcat/Km by single mutations, yet the underlying mechanism remains unclear (vide infra). Second, the allosteric mechanism of residues beyond the second-shell is usually complex, sensitive to the specific structural features of the system and therefore less representative and transferable to other enzymes. For example, recent analysis of Markin et al.44 found that while the effects of second-shell mutations on kcat/Km generally correlate well with those on the binding affinity of the transition state analogs, the impacts on these properties due to residues further away exhibit much less clear correlations.

The roles of these second-shell residues are not well understood based on either experiments or computations despite their relative proximity to the active site. With the simplest model, they are believed to impact catalysis by largely modulating the conformational distributions of the first-shell residues35,36,44 via either steric packing with non-polar second-shell residues, or hydrogen-bonding networks involving a polar second coordination shell. Second-shell residues may also control other important characteristics of the active site, such as electrostatics45,46 and the level of hydration. Since transition state stabilization is a fundamental feature of enzymes, it is often assumed that the positioning effect of second-shell residues is manifested in the transition state.44 However, considering the fact that the catalytic properties of enzymes involve multiple functional states, it remains unclear in which functional state(s) the positioning effect of second-shell residues is most impactful. Unfortunately, it is often the case that not all steps or functional states are accessible to high-resolution experimental characterizations, which limits the understanding of second-shell contributions. For example, the measured kinetics for MeP hydrolysis are multi-step in nature (Fig. 1c). However, only kcat/Km values were measured for the large set of PafA mutants. The rate for the limiting chemical step kchem,1 was not possible to measure reliably due to the non-fluorogenic substrate. Instead, generated inorganic phosphate from the subsequent hydrolysis step is quantified over time via fluorescence indirectly using a coupled assay, making it difficult to determine whether the second-shell mutation effects were largely on the chemical step or substrate binding, or which functional states are most perturbed. Similarly, previous computational studies of distal mutation effects rarely examined all the essential steps in the catalytic cycle; they either focused on perturbation of the chemical step47–51 or residues that exhibit motional coupling with binding or conformational equilibria in the active site.17,25,26,29 To establish the contributions of second-shell residues, it is necessary to explicitly analyze multiple enzymatic states, which in turn requires striking the proper balance between accuracy in energetics and efficiency in conformational sampling. Meeting such requirements is particularly challenging for metalloenzymes such as PafA, since metal-ligand interactions generally require sophisticated computational models to properly treat ligand polarization, coordination geometry and flexibility, and metal/ligand charge transfers.52,53 Specifically, we conduct a multi-faceted computational analysis of the impact of several second-shell mutations in PafA on both the rate-limiting phosphoryl transfer step and the properties of all relevant enzyme states explicitly. These include quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) free energy computations based on the third-order Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB3) model,54 extensive molecular mechanical molecular dynamics simulations and Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations of active site cluster models. Combined together, these simulations reveal the magnitude of perturbations in key active site properties and the impact on catalytic efficiency upon second-shell mutations. Our results, in combination with the available experimental data,40,44 suggest that the studied second-shell mutations in PafA impact catalysis mainly through modulation of the apo state and thus substrate binding, while they do not perturb the ground state or the nature of phosphoryl transfer transition state significantly despite proximity to catalytically critical residues. In other words, the “positioning” effect of many second-shell residues is most manifested in the apo state of PafA. Several mutations also alter the active site hydration level, which in turn impacts the energetics of phosphoryl transfer. In addition to providing fundamental mechanistic insights into second-shell effects, our analyses motivate the discussion of several strategies that may help further improve enzyme designs by going beyond first-shell residues.

Materials and Methods

Basic QM/MM Setup

The model is constructed based on the crystal structure of wild type PafA at 1.7 Å resolution (Protein Data Bank entry 5TJ341) and solvated with a 25 Å water droplet centered at the outer catalytic Zn2+ ion in the active site. All second-shell mutations are generated in silico. The QM region is treated at the DFTB3 level of theory55 with the 3OB-OPhyd parameter set56–58 and Grimme’s third version semi-empirical dispersion (D3) correction.59 It includes the two catalytic Zn2+ ions and their full coordination shells (D305, H309, H486, H353, D38, and D352), the substrate MeP, the deprotonated and nucleophilic T79, and residues that are directly interacting with the phosphate (K162, R164 and N100). H309, H353, and H486 are protonated at Nδ as the two catalytic zinc ligands, and all other titratable side chains are kept in their standard protonation states. Hydrogen atoms are added with the HBUILD module of CHARMM.60 Only side chain atoms of protein residues are included in the QM region, and link atoms are introduced between Cα and Cβ to saturate the valence of the QM boundary atoms using the Divided Frontier Charge (DIV) scheme.61 All solvent molecules, including those in the active site, are treated at the MM level so that all enzyme variants studied here can be compared in a consistent fashion (see discussion below).

Previous studies of AP found that DFTB3(/MM) generally gives reasonable transition state structures for the phosphoryl transfer reaction based on comparison of cluster models to DFT calculations, and kinetic isotope comparison to experimental values.62,63 Since the effects are expected to be modest for the second coordination shell mutations, balancing the computational efficiency and degree of sampling is critical for distinguishing different systems with statistical significance. The results shown in Table 1 and Fig. S3 support the unique value of DFTB3/MM with generalized solvent boundary potential64,65 (GSBP) for the purpose of this work.

Table 1:

Key Features of the Computed Free Energy Profiles for the Phosphoryl Transfer Step from QM/MM Simulations and Available Experimental Data

| Systems | ξTSa (Å) | ΔG‡ (kcal/mol) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) | Kib (μM) | c (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 0.35 | 12.2 (0.2) | −1.4 (0.1) | 6.1×105 | 6.1×102 | 0.7 (2.2) |

| A302V | 0.35 | 12.1 (0.9) | −5.2 (2.0) | 2.9×104 | 7.9×102 | 23.9 (78.1) |

| Y112V | 0.35 | 13.2 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.2) | 4.6×104 | 4.6×103 | 2.6 (45.6) |

| D163V | 0.35 | 10.4 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.3) | 7.1×104 | 5.1×103 | − (10.9) |

| YDd | 0.35 | 13.3 (0.4) | 2.2 (0.5) | – | – | – |

The location of the TS (ξTS) is determined by the peak position of the computed potential of mean force (Fig. S3). The values in the parentheses for ΔG‡ and ΔG are the corresponding statistical uncertainties (see Materials and Methods for details).

The experimental Ki values are for inorganic phosphate.40

Dissociation constants for two transition state analogs (TSAs);44 the values without parentheses are for vanadate, and those with parentheses are for tungstate.

YD stands for the Y112V/D163V double mutant.

In the GSBP framework, the inner region contains atoms within a 27 Å-radius sphere centered on the outer Zn2+ ion and Newtonian equations of motion are solved within 25 Å. Protein atoms in the buffer region (25–27 Å) are harmonically restrained with force constants determined from the crystallographic B factors66 and Langevin equations of motion are solved with a temperature bath of 300 K. Protein atoms in the MM region are described by the CHARMM36 force field67 and water molecules are described with the TIP3P model.68 All water molecules are subject to a weak GEO type of restraining potential60 to keep them inside the inner sphere. Electrostatic interactions among inner region atoms are treated with the extended electrostatics and a group-based cutoff scheme. The static field due to the outer region atoms, φ, is evaluated with the linearized Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equations using a focusing scheme, which employs a coarse grid of 1.2 Å and a fine grid of 0.4 Å. The reaction field matrix M64,65 is evaluated using spherical harmonics up to the 20th order. In the PB calculations, dielectric constant of the protein and water is set to 1 and 80, respectively, and the salt concentration is set to 0. The remaining portion of the system in the outer region is frozen with an implicit solvent scheme.

QM/MM Equilibrium and Metadynamics Simulations

After minimization and heating, each system is equilibrated sequentially with gradually releasing restraints on the substrate and the nucleophile for 3 × 250 ps with a 1 fs time step at 300 K. All bonds involving hydrogen are constrained with the SHAKE algorithm.69 The last frames are saved as the corresponding starting structures for metadynamics simulations. To probe the properties of the apo state, equilibrium simulations are carried out by removing the substrate MeP from the corresponding equilibrated bound state simulations.

Multiple-walker metadynamics simulations70 are carried out using the PLUMED71,72 CHARMM interface. In this work, we focus on the phosphoryl transfer step, which is expected to be the rate-limiting step during the catalytic cycle for alkyl phosphate monoesters.41,42 The anti-symmetric stretch that describes the phosphoryl transfer process between the substrate and T79 is chosen as the collective variable (CV), i.e., ξ = r(P-Olg) r(P-Onuc). The corresponding P-Olg distance and P-Onuc distance are also monitored and restrained with both a lower (1.5 Å) and an upper (3.0 Å) wall.

The first two metadynamic runs are not well-tempered for the efficiency of sampling. In the subsequent well-tempered runs,73 the bias factor is set to be 35. A new Gaussian biasing potential is added every 0.2 ps with an initial height of 0.3 kJ/mol and a width of 0.1. Twenty five walkers with different initial velocities are used per simulation in parallel while sharing hill history with other walkers every 1 ps. The convergence is confirmed by comparing the PMF as a function of the number of Gaussians added. The simulation is stopped when adequate convergence has reached, which typically takes 300 – 500 ps per walker in each independent metadynamics run.

Data Analysis for Metadynamics Simulations

Metadynamics trajectories are analyzed using the metadynamics reweighting algorithm implemented in the PLUMED package (version 2.8)72 to obtain the unbiased distribution of the collective variables, which is then converted into the 1D PMF. The metadynamics simulations for each system are repeated three times with different initial velocities to ensure the reproducibility of the computed free energy profiles and estimate statistical uncertainties. The final 1D PMF of each system is the average of the three independent runs, and the shaded area in the PMF plot represents the standard error of the mean (SEM) of the three replicas; the SEM (Fig. S3) is visibly larger in the reactant region in all PafA variants studied here, especially for A302V, which is consistent with the higher degree of conformational heterogeneity of the substrate prior to the TS. The range of the collective variable that represents the transition state is defined as a narrow region (±0.1Å) around the peak of the barrier in the 1D PMF, while the ranges of the collective variable that represent the ground state and the product state are defined as the narrow regions around the two wells located on the left and right sides of the transition state, respectively. The snapshots that belong to a particular state are therefore selected from the metadynamics trajectories according to the corresponding values of collective variables and then reweighted by the similar protocol as stated above to obtain the unbiased distributions of the distances, dihedral angles, and water radial distribution functions of each state. The final distributions are the corresponding average of the three independent runs.

Molecular Mechanical Molecular Dynamics Simulations

To supplement the QM/MM simulations, especially further extending the sampling time scale, molecular mechanical MD simulations are conducted for the WT PafA and several second-shell mutants in both ground and apo states. The starting structure is the same crystal structure used to set up the QM/MM simulations. The phosphorylated T79 in the crystal structure is converted to a deprotonated threonine and MeP substrate for the ground state simulations. H309, H353, and H486, which form close interactions with the two catalytic Zn2+ ions, are protonated at the Nδ position. All mutations are generated in silico. CHARMM-GUI74 is used to solvate the system in TIP3P water68 cubic boxes with a 10.0 Å edge distance under periodic boundary conditions (PBC), and randomly place 150 mM NaCl ions to neutralize the system and mimic the physiological condition. The initial simulation box size is around 97 × 97 × 97 Å3 with a total number of atoms around 91,000.

Zn2+ ions are treated using the standard CHARMM force field model.67 The parameters for MeP substrate are available in the CHARMM general force field (CGenFF).75 Particlemesh Ewald summation76 is used to calculate electrostatic interactions. Van der Waals interactions are treated with a cutoff distance of 12 Å and a switch distance of 10 Å. The SHAKE algorithm69 is used in all simulations to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms. Systems are energy minimized with the steepest descent and Adopted Basis Newton-Raphson algorithms before equilibration runs with a time step of 1 fs in CHARMM60 for 500 ps in the NVT (constant particle number, volume and temperature) ensemble. Weak harmonic restraints are applied to protein backbone (force constant: 1 kcal/(mol·Å2)) and sidechain (force constant: 0.1 kcal/(mol·Å2)) heavy atoms during equilibration runs. NPT (constant particle number, pressure and temperature) production runs are carried out with a time step of 2 fs using OpenMM 7.377 with GPU acceleration for 600 ns. In both equilibration and production runs, a harmonic restraint is applied to maintain the proper distance between the two catalytic Zn2+ ions (force constant: 200 kcal/(mol·Å2)). To mimic the ground state, the angle formed by Oγ1 in T79, P1 and O1 in MeP is also harmonically restrained around 180 degrees (force constant: 40 kcal/(mol·degree2)). All simulations are maintained at 303.15 K and under 1 bar. The Langevin integrator with a friction coefficient of 1 ps−1 and MonteCarloBarostat with the pressure coupling frequency of 100 steps is used in OpenMM production runs. Apo state simulations are carried out by removing the substrate MeP from the corresponding equilibrated bound state simulations and follow the same protocol.

Quantum Mechanical Cluster Model Calculations

Active site cluster models are constructed to evaluate the intrinsic reactivity of the bi-metallic motif and sensitivity of transition state to the explicit inclusion of second-shell residues. Three sizes of clusters are constructed. The smallest cluster (QM1) includes essentially the same QM region in the QM/MM simulations: the bimetallic motif (i.e., the two catalytic Zn2+ ions and their ligands), the nucleophile (T79), the MeP substrate, and the first-shell residues in direct contact with the substrate (N100, K162 and R164). The larger QM2 model further includes the sidechain of Y112, and the largest QM3 model includes the sidechains of both Y112 and D163. Therefore, the difference between QM3 and QM2 mimics the effect of the D163V mutation, and the difference between QM3 and QM1 reflects the effect of the Y112V/D163V double mutation.

The initial structure of the cluster model is taken from the transition state window in QM/MM simulations. The Cβ atoms are fixed in space to mimic the structural constraint of the protein environment. The rest of the structure is fully relaxed in geometry optimizations for the ground state, the transition state and the final product state with the Becke, threeparameter, Lee-Yang-Parr exchange-correlation functional (B3LYP),78–80 the LANL2DZ81 basis set and effective-core-potential for the zinc atoms, and the 6–31G(d,p) basis set82 for the other atoms using the Gaussian 16 program;83 empirical dispersion interactions are included with the original D3 model of Grimme.84 Conductor-like polarizable continuum solvation model (CPCM)85,86 with a dielectric constant of 20 is used to crudely mimic the solvent-accessible nature of the active site; a dielectric constant of 4.0 is also tested and found to lead to only modest changes in energetics (see Table S2). The transition state is a true first-order saddle point as verified by frequency calculations. Single point energy calculations are performed with a larger basis set, Def2TZVP.87,88 Zero-point vibrational corrections and thermal contributions to free energy at 300 K are evaluated based on frequency calculations for the optimized structures.

In addition to the phosphoryl transfer reaction, tungstate binding mode is also probed with the three QM cluster models using similar DFT/CPCM calculations. Two different protonation states for the tungstate (fully deprotonated and singly protonated) are considered. The structures are optimized with the B3LYP-D3 method as specified above, using the LANL2DZ81 basis set and effective-core-potential for the zinc and tungsten atoms, and the 6–31G(d,p) basis set82 for the other atoms.

Results

Transition State Properties Remain Largely Invariant upon Second-shell Mutation

Our QM/MM simulations find that the transition state (TS) of the MeP substrate in the WT is rather tight, with the breaking phosphorus-leaving group oxygen (P-Olg) and forming phosphorus nucleophile oxygen (P-Onuc) bond distances of 1.81±0.05 Å and 1.99±0.05Å respectively (Table S4, Fig. S4). Regarding the effect of second-shell mutations, we note that the nature of the TS remains largely invariant among the PafA variants studied here; as shown in Table 1, the location of the TS along the reaction coordinate (difference between POnuc and P-Olg distances) is the same at 0.35 Å among the systems studied (also see Table S4 and Fig. S4 for the distribution of P-Onuc and P-Olg distances). The location of the TS is also at ξTS ~ 0.3 in the QM cluster models optimized at the B3LYP-D3 level, regardless of the cluster size (Tables S1, S2), further supporting the validity of the DFTB3/MM simulations and insensitivity of the TS to the second-shell residues.

These P-O distances are close to those observed in the closely related E. coli alkaline phosphatase (AP) with ethyl phosphate monoester as the substrate in our previous study.62 Such similarity in TS structures is largely expected due to the conserved bi-metallo motifs and similar first-shell residues in PafA and AP:41,42 in PafA, the phosphate and the leaving group are stabilized directly by two cationic residues (K162, R164, Fig. 1b), and two chargeneutral polar groups (sidechain of N100 and backbone amide of the nucleophile, T79), while in AP, the phosphate and the leaving group are also stabilized by a nearby arginine R166, a magnesium site and backbone amide of the nucleophile residue, S102. Both active sites are also solvent accessible. Solvent molecules are observed to provide considerable stabilization as well.

In terms of nearby residues and interactions that help position critical first-shell residues, K162 is sandwiched between two aspartates D38 and D305 from the bi-metallic zinc motif and the nucleophile T79. R164 is engaged in a hydrogen-bonding network involving Y112 and D163 (Fig. 1a), while N100 is not involved in any apparent second-shell polar interactions due to its rather solvent-accessible location. We focus here on the key distances of the hydrogen-bonding network in the active site (Fig. 2, Figs. S5–S6) between the substrate and the three first-shell residues (N100, K162, R164), the “outer” zinc ion that helps stabilize the leaving group, and active site level of hydration (Fig. S8).

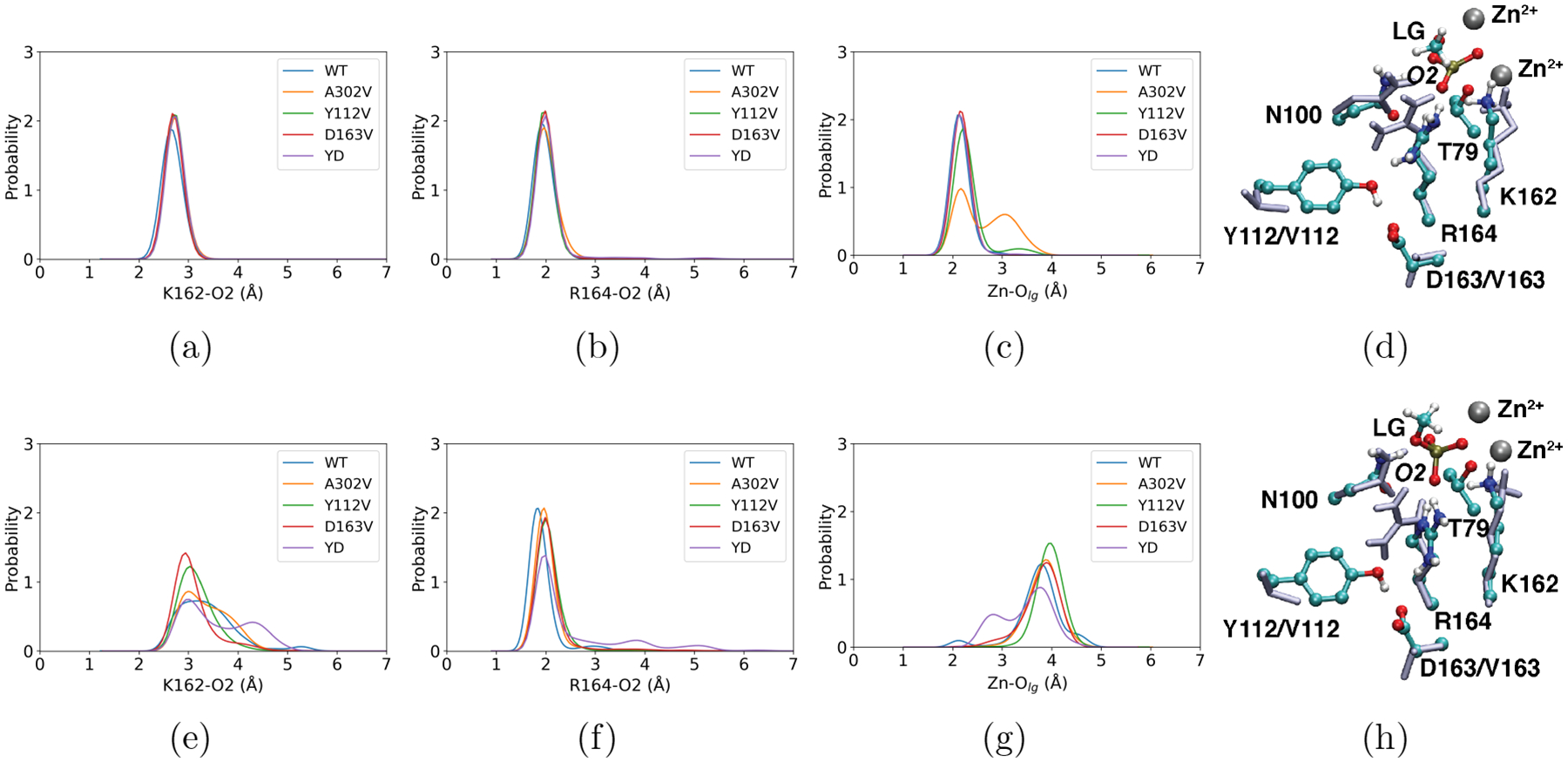

Figure 2: Modest perturbation of the active site structure in the transition state (TS) and ground state (GS) due to the second-shell mutations from QM/MM simulations.

The distributions of key hydrogen-bonding distances between the substrate (MeP) and first-shell residues, including (a, e) K162 and (b, f) R164. (c, g) The distance distribution between the outer Zn2+ ion and the methoxy leaving group, -OMe. The first and second rows represent distributions in the TS and GS regions, respectively. Additional distance and dihedral angle distributions are presented in Figs. S5–S7, further highlighting the even smaller perturbations of the structural properties in the TS as compared to the GS. Representative snapshots of the active site from (d) TS and (h) GS are shown. First-shell residues (T79, N100, K162, and R164) and the double mutation sites (Y112 and D163) in both the WT (colored by atom types) and the double mutant Y112V/D163V (YD, ice blue) are overlaid. Molecular mechanical MD simulations at substantially longer time scales (~600 ns) lead to similar observations for the GS, as shown in Figs. S10–S11.

In the TS, all key hydrogen-bonding distances between the first-shell residues and the substrate phosphate remain highly similar among the PafA variants (Fig. 2a–b, Figs. S5–S6); similarly, these hydrogen-bonding interactions remain essentially invariant as second-shell residues (Y112, D163) are excluded from the QM cluster model optimized at the B3LYP-D3 level (see Fig. S1, Table S1). These observations clearly highlight that PafA has evolved to bind tightly to the TS, so that key stabilizing interactions are maintained even when the supporting hydrogen-bonding network is perturbed in these second-shell mutants. The only notable perturbations in the TS active site are the orientation of R164 sidechain (Fig. 2d, Fig. S7) and the distance between the outer zinc ion and the leaving group (Fig. 2c); the latter distribution exhibits a second peak in the A302V mutant, suggesting that the leaving group is partially stabilized by active site water instead of the outer zinc ion.

Modest Perturbation of the Bound States Does Not Slow Down the Phosphoryl Transfer Step Significantly

Most structural properties of the ground states (GS) and product states are preserved with subtle changes in the first-shell across the WT and mutants studied here, suggesting that in general, the bound states are rather well organized, especially the O2 side (see Fig. 1b for labels of key atoms in the active site). The dominant positions of the first-shell residues (as reflected by the peak positions of the relevant distance distributions) remain unaltered in the second-shell mutants (Fig. 2e–f); this is further supported by molecular mechanical MD simulations at substantially longer time scales (~600 ns), which observe highly similar distributions across the WT and mutants studied here for the key distances (Fig. S10) and dihedral angles (Fig. S11) involving first-shell residues. The only exceptions are the positioning of K162 and R164 in the GS (Michaelis complex), which is perturbed in Y112V and D163V, and to a larger degree in the Y112V/D163V double mutant; both K162 and R164 are able to sample a broader set of distances to the substrate phosphate O2. Apparently, the hydrogen-bonding network provided by the second-shell residues (e.g., Y112 and D163) helps position R164 and plays a role in modulating the conformational distribution of first-shell residues (both K162 and R164) in the GS.

The computed potential of mean force (PMF) (Fig. S3a) for the MeP substrate in the WT indicates that the phosphoryl transfer step has a free energy barrier of ~12.2±0.2 kcal/mol and a nearly thermoneutral phosphoryl transfer reaction that leads to the covalent phosphoenzyme intermediate (Table 1). Experimental measurement for MeP41 observed a kcat/Km value of 8.5×104 M−1s−1, which corresponds to a free energy barrier of 10.8 kcal/mol relative to the apo enzyme and substrate in standard states in solution. Therefore, considering the typical binding free energy of substrates in PafA (e.g., Ki for the inorganic phosphate40 is ~6×102μM, which corresponds to a standard binding free energy of ~4.5 kcal/mol), the free energy barrier for the phosphoryl transfer reaction is ~15 kcal/mol, which is close to the values from QM cluster models at the B3LYP+D3-CPCM/def2TZVP level (Table S2). Therefore, our DFTB3/MM simulations likely underestimate the free energy barrier by 2–3 kcal/mol. Since the quantities of main interest here are the changes in the free energy barrier due to mutations, the systematic underestimate of the absolute barrier is not a concern for the purpose of this work.

The studied second-shell mutations do not perturb the free energy barrier significantly (Table 1). In D163V, the free energy barrier is lower than the WT by a statistically significant amount of ~ 2 kcal/mol. The barrier is slightly higher, with statistical significance, in Y112V and the double mutant Y112V/D163V. Even in the Y112V/D163V double mutant, however, the increase in the free energy barrier is ~1 kcal/mol, not statistically different from Y112V. The same trends are qualitatively observed in the QM cluster models at the B3LYP+D3-CPCM/def2TZVP level (see Table S2), providing further support to the DFTB3/MM free energy results. For A302V, the free energy barrier is statistically indistinguishable from the WT. These limited levels of sensitivity of computed free energy profile to second-shell mutations is partly due to the solvent accessibility of the PafA active site, in which any broken hydrogen-bonding interaction between the substrate and first-shell residues (e.g. R164 in some snapshots in Y112V/D163V) is readily compensated by penetrated water molecule(s).For a similar reason, the free energy barrier in A302V is observed to be close to that in the WT enzyme, despite the notably different interaction pattern between the outer zinc and the leaving group in the TS (Fig. 2c; see below for additional discussion). These observed differences in the barrier heights and experimentally determined kcat/Km values (see Table 1) suggest that changes in substrate binding represent a significant component of the mutation effects (vide infra).

The exergonicity of the phosphoryl transfer step is observed to exhibit larger variations due to the mutations. Compared to the WT enzyme, the reaction is less favorable in Y112V,D163V and the Y112V/D163V double mutant, while more favorable in the A302V mutant.The longer R164-O2 distances observed in the product states of Y112 and D163V (Fig.S5) are consistent with the less favorable exergonicity of the reaction for these mutants. Also, A302V has clearly enhanced local hydration level and different leaving group-zinc coordination in the product state (Figs. S6, S8).

Second-shell Mutations Perturb the Apo States More Significantly

As alluded to earlier, the trends in the computed PMFs for the phosphoryl transfer step do not always follow the experimental trends in kcat/Km, suggesting that substrate binding is perturbed in many mutants studied here. In principle, changes in binding affinity can be caused by perturbations either in the apo state or the GS, or both. The structural analysis presented in the last subsection indicates limited changes in the interactions between the substrate and first-shell residues in the GS, thus we explore perturbations in the apo state due to the various second-shell mutations.

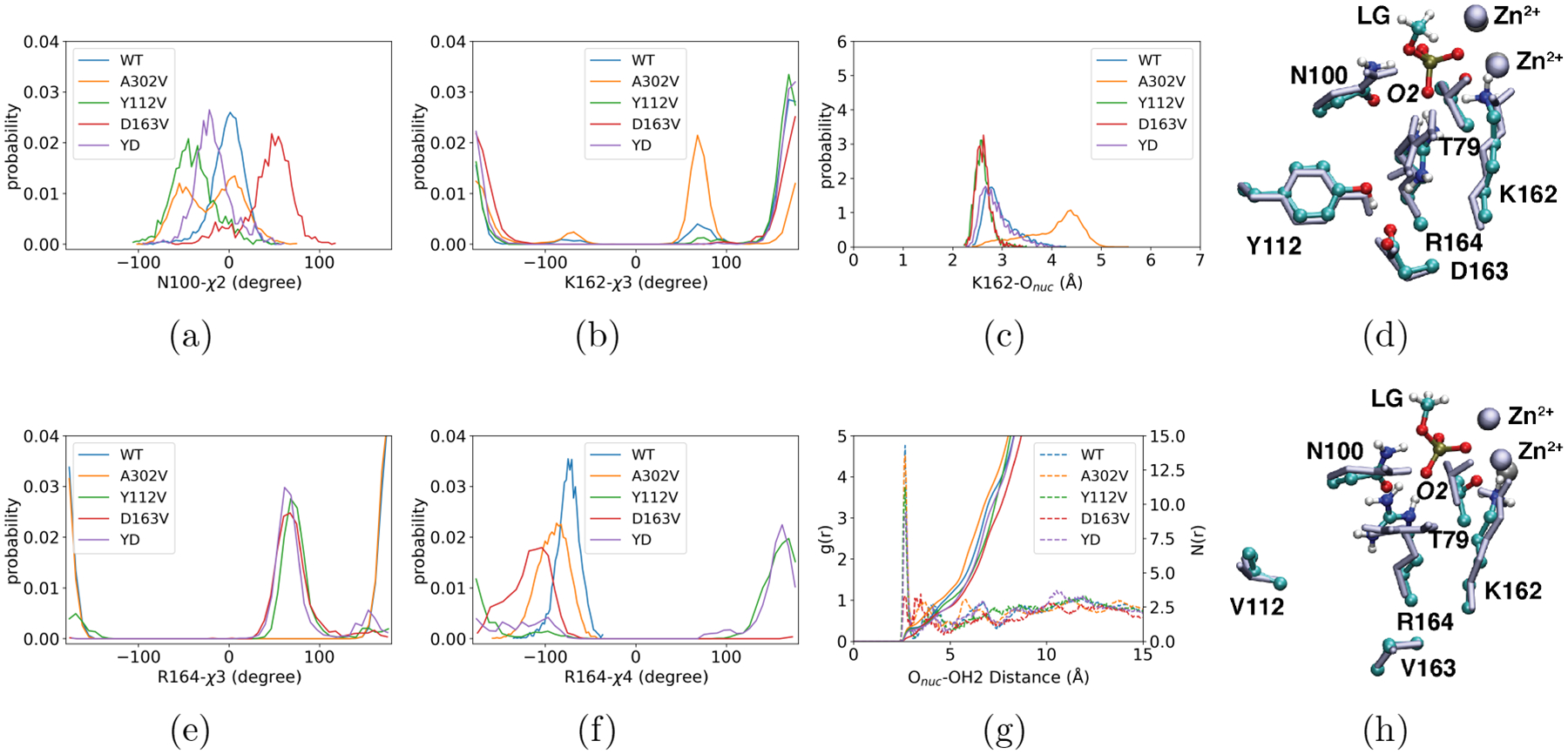

It is evident that more significant differences are observed in the apo state in positioning of the first-shell residues that help bind and properly align the substrate (Fig. 3). For example, the χ2 of N100 peaks around zero degree in the WT enzyme, while it is perturbed significantly toward −60 and +60 degrees in Y112V and D163V, respectively; in A302V, the distribution becomes bimodal, with peaks around 0 and −60 degrees. The position of K162 is most significantly perturbed in A302V, as reflected clearly by the distributions of χ3 and distance to the nucleophilic oxygen. For R164, the orientation of the guanidinium group is shifted significantly by mutations involving the Y112-D163 network, as revealed by the distributions of χ3 and χ4 angles. Moreover, the hydration level of the active site is observed to undergo substantial increase and decrease in the A302V and D163V mutants, respectively (Fig. 3g). Notably, deviations in these distances, dihedral angles and hydration level are substantially smaller in the GS of the second-shell mutants (Figs. S5–S8), supporting the notion that these additional structural “relaxations” mainly occur in the apo state, reducing the corresponding binding affinity of the substrate in these mutants. Indeed, more significant structural differences at the active site between the apo and GS are visible in the studied second-shell mutants (Y112V/D163V shown in Fig. 3h as an example) than in the WT (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3: More significant perturbation of the active site in the apo state due to the second-shell mutations from QM/MM simulations.

The dihedral angle distributions of some first-shell residues, including (a) the χ2 angle in N100, the χ3 angle in (b) K162 and (e) R164, and (f) the χ4 angle in R164. (c) The distance distribution between the nucleophile T79 and K162. (g) The radial distribution function of water oxygen as a function of the distance from the nucleophile oxygen. Dashed lines in (g) represent the radial distribution functions, g(r), measuring the local water density at distance r from the nucleophile oxygen relative to the bulk; the solid lines represent the cumulative distribution functions, N(r), indicating the number of water molecules within a distance r from the nucleophile oxygen. YD stands for the double mutant, Y112V/D163V. For the corresponding comparison with the bound state distributions, see Figs. S5–S7. In (d) and (h), representative snapshots for the active site are overlaid for the apo (ice blue) and ground (colored by atom type) states. While only small changes are observed for the WT enzyme in (d), more notable structural differences in T79, N100 and R164 are seen for the Y112V/D163V double mutant in (h). Molecular mechanical MD simulations at substantially longer time scales (~600 ns) observe similar trends in the variations of first-shell residues orientations and active site hydration levels (see Figs. S12–S13, and snapshots in Fig. S14).

For all PafA variants studied here, the apo and bound (e.g. TS) states show comparable magnitudes of residual fluctuations as the WT (shown as the difference in the sidechain root mean square of fluctuation between the mutant and WT, dRMSF, Fig. S9). While minor differences in the region surrounding residue N100 can be observed, the dRMSF mapping suggests a similarly modest level of perturbation in the residual fluctuation due to mutation across different enzymatic states, including the apo state. This is understandable because, even following mutation of the second-shell residues, the active site still features strong interactions among polar and/or charged residues. Thus structural reorganization in the active site required by tight substrate binding in the mutants is expected to be associated with a free energy cost not readily overcome through thermal fluctuations.

The larger structural perturbations observed for the apo state of second-shell mutants compared to the GS are supported by molecular mechanical MD simulations at longer time scales (~600 ns). For example, much larger variations in the χ1 distributions of K162, χ2 distributions of N100, K162 and R164, and χ4 distribution for R164 are observed in the apo state (Figs. S12) than the GS (Fig. S11), in qualitative agreement with QM/MM simulations (Fig. 3). Longer sampling in the molecular mechanical MD simulations leads to even more visible displacement of N100 and R164 sidechains in the absence of the substrate (Fig. S14), with limited changes in the backbone. Therefore, both QM/MM and MM MD simulations underscore the role of the second-shell residues in positioning the first coordination shell for tight substrate binding.

Discussion

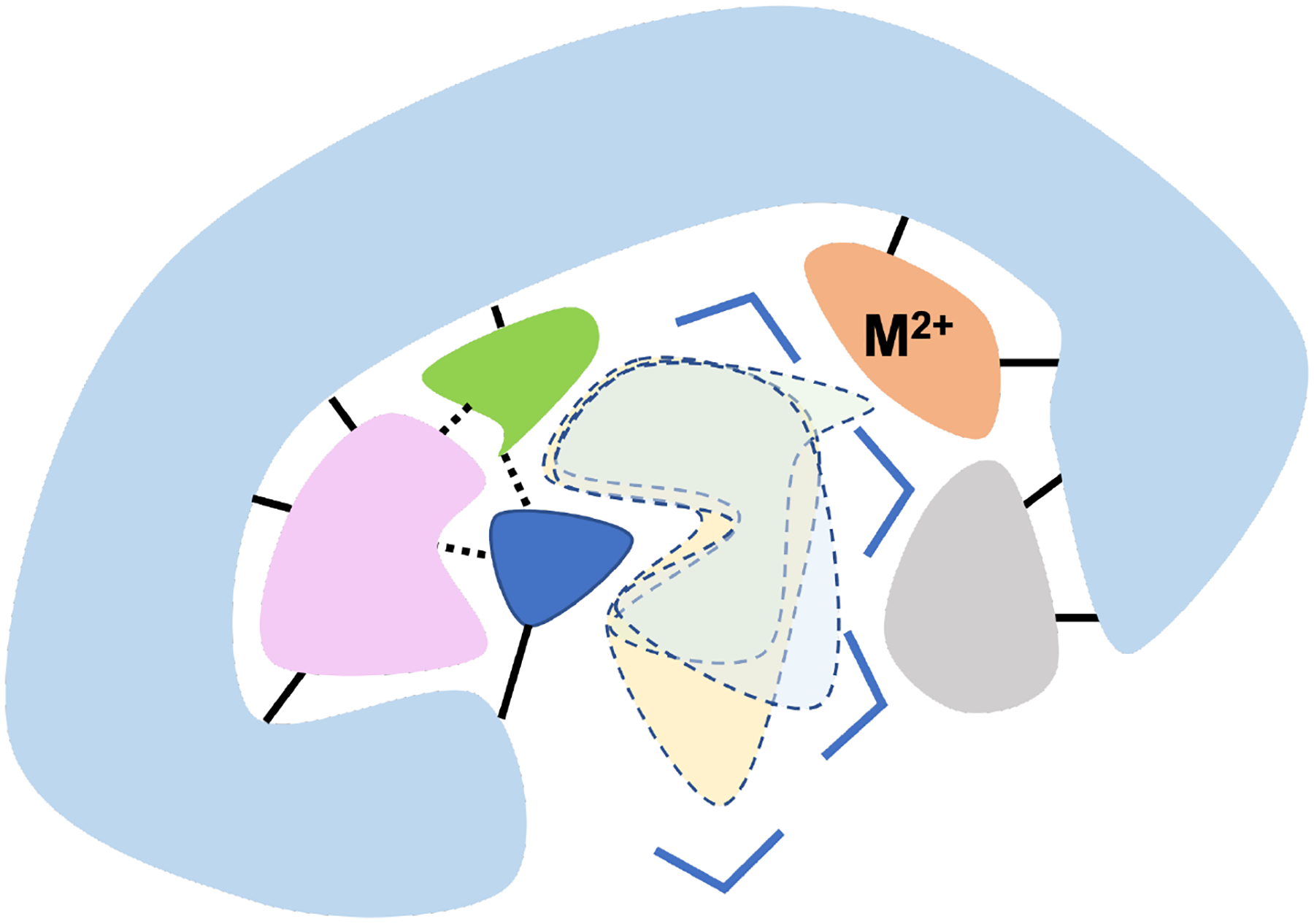

Experimental studies by Markin and co-workers40 observed that many second-shell mutations in PafA led to notably reduced kcat/Km values, while the underlying mechanism(s) remained unclear. As shown schematically in Fig. 4a–c, there are at least three possible limiting scenarios that second-shell mutations lead to a decrease in kcat/Km. In essence, a mutation may either increase the barrier for the chemical step (Fig. 4a) or decrease substrate binding affinity (Fig. 4b–c), in contrast to what is commonly assumed that second-shell residues mainly help position catalytic groups for most efficient transition state stabilization. Even with explicit measurements of binding affinity, it is difficult to determine whether the perturbation by mutation is mainly in the GS or in the apo state. By combining our computational results and available experimental data,40,44 we are able to gain further insights into the molecular contributions of second-shell residues to catalysis in PafA. In particular, our simulations and calculations clearly indicate that second-shell mutations modulate structural features of the first-shell residues especially in the apo state, as well as the hydration level of the active site.

Figure 4: Second-shell residues may contribute to catalysis in distinct ways.

For reduced kcat/Km, second-shell mutations may either (a) increase the barrier for the chemical step or (b, c) decrease the substrate binding affinity without perturbation of the chemical step; for the latter, the major perturbation relative to the WT may occur either in the (b) ground state (GS), or in the (c) apo state. Also shown in each case is the solution transition state, TS (aq), which helps define the binding affinity of the transition state (analog). Note that depending on whether the chemical step or the binding step is perturbed by mutation, different trends are expected for the changes in the activation free energy that corresponds to kcat/Km, , the binding free energy of TS(A), , and the binding free energy of GS(A), . In the schematics, black lines represent the wild type (WT), while red lines represent the mutant (MT); the x axis represents the reaction coordinate and the y axis represents the free energy change relative to the WT apo state plus the substrate in solution. (d-f) Schematics that illustrate how second-shell mutation potentially leads to perturbation of the first coordination shell (using the orientation of R164 as an example) predominately in different functional states: (d) the transition state; (e) the ground state; (f) the apo state; the blue region indicates that the active site is occupied by solvent in the apo state.

Second-shell Residues Pre-organize the First Coordination Shell for Substrate Binding

Both QM/MM and MM MD simulations indicate that the second-shell mutations studied here perturb the apo state in much more pronounced manners (Figs. 2–3 vs. Figs. S5–S7, and Fig. S11 vs. S12). In the absence of a charged substrate, the position and orientation of first-shell residues are more readily perturbed and stabilized to adopt alternative conformations by second-shell mutations. Note that such “stabilization” does not suggest that the apo state of the mutant has a higher thermodynamic stability than the WT (i.e., stability relative to the unfolded state); rather, the larger perturbation on the apo state relative to the bound states (GS and TS) suggests that the active site is not well set up for tight substrate binding in the apo state of the mutant, thus an additional “activation”, or induced fit, is required to reach the favorable binding conformation, leading to the reduced apparent binding affinity of the substrate.

Our reasoning is consistent with the experimental observation that inorganic phosphate inhibition gets reduced by all the second-shell mutations studied here; i.e., since substrate binding affinities in these mutants have not been measured explicitly, the reported Ki values can be used as proxies for substrate binding. For example, as shown in Table 1, the Ki values for the WT and D163V are 6.1×102 and 5.1×103 μM, respectively. In other words, the inferred decrease in substrate binding in D163V is on par with the reduction in kcat/Km (a factor of 9, see Table 1) observed experimentally,40 thus supporting our model that weakened substrate binding contributes significantly to the reduction in catalysis in D163V.

Additional insights into the relative magnitudes of perturbation on the chemical step vs. substrate binding in phosphoryl transfer can be gleaned from recent experimental data on the binding affinity of transition state analogs (TSAs, vanadate and tungstate) in PafA mutants.44 Along this line, tungstate has been argued to be a better TSA than vanadate for phosphoryl transfer in AP;89 as shown in Table S3 and Fig. S2 with DFT cluster calculations, tungstate in the singly protonated state indeed resembles the TS fairly well, in terms of both interactions with the nucleophile oxygen, first-shell residues, as well as the limited impact of second-shell residues on the binding mode. As shown schematically in Fig. 4a, if the chemical step is significantly perturbed by a mutation, the changes in the activation free energy (corresponding to kcat/Km) and TSA binding affinity are expected to be similar in magnitude, while larger than the change in the ground state analog (GSA) binding affinity. On the other hand, if the binding step is mainly perturbed by a mutation, the changes in activation free energy, TSA binding affinity and GSA binding affinity are all expected to be similar in magnitude. As highlighted in Fig. 4b and 4c, however, the trends in these free energy changes do not reveal whether the mutation mainly perturbs the GS or the apo state, which again underscores the importance of explicitly sampling all relevant functional states with molecular simulations.

For D163V, the measured decrease in kcat/Km with MeP (all experimental data were reported as 2 based logarithm values for the ratio of WT and mutant properties40,44) is −3.1, which is close to the increase of 3.1 in the Kd of Pi; the increase of tungstate Kd is slightly lower, 2.3.44 By comparison, for Y112V, the measured decrease in kcat/Km with MeP is −3.7, the increase in Kd of Pi is 2.9, and increases in Kd of tungstate is 4.4. Bearing in mind the limitation that tungstate does not reflect a true transitions state44,90 (also see key structural differences in DFT cluster models in Tables S1 and S3), these results suggest that weakened substrate binding makes the major contribution to the decrease of catalytic efficiency in D163V, while perturbations in both binding and the phosphoryl transfer chemical step contribute to the decrease in catalysis in Y112V. These interpretations are in line with our computational findings (Table 1) and the mechanistic model (Fig. 4). For the Y112V/D163V double mutant, our results indicate that perturbations in both phosphoryl transfer chemical step and substrate binding contribute to the decreases in catalysis, similar to the situation of Y112V; such prediction can be tested by future experiments.

We also note that the effect of second-shell mutation on binding can be substratedependent. While positioning first-shell polar/charged residues is critical to the binding of phosphate monoesters, it is expected to be rather different for phosphate diesters. Previous studies41 established that the extra ester group is oriented towards K162 and R164, while the anionic phosphate oxygen is stabilized by N100. Therefore, the second-shell mutations studied here, which interact directly with R164, are not expected to reduce diester binding; in fact, the mutation of polar (Y112) and charged (D163) residues into hydrophobic ones (V) is expected to form more favorable non-polar interactions with the ester groups (Me and cMU),40 leading to a higher binding affinity of the diester substrate. This reasoning is supported by the experimental observation that for many second-shell mutations near K162 and R164, the differential effect of mutation on the kcat/Km values of monoester (MeP) and diester (MecMUP) substrates (FC1 values) is larger than the corresponding changes in the monoester (MeP) activities.40 Since the phosphoryl transfer step of diester hydrolysis is not expected to be affected directly by mutations near K162 and R164,41 the larger FC1 values strongly suggest increased diester binding affinities in these mutants.

Collectively, QM/MM and MM simulations, as well as DFT cluster calculations consistently demonstrate that key features of the bound states (GS and TS) remain largely unperturbed upon second-shell mutations. This observation highlights that the active site of PafA, which is one of the most efficient enzymes, has evolved to stabilize the bound states in a robust fashion. This feature is likely dictated by the strong electrostatic interactions provided by the bi-metallic core and surrounding charged residues in the first coordination shell of the substrate. However, second-shell residues are able to play a major role in pre-organizing the apo state for the tight binding of charged substrates; i.e., they help position the first-shell residues through hydrogen-bonding and steric interactions to establish the favorable binding configurations and therefore make crucial contributions to the catalytic efficiency of an enzyme, which is usually defined as (kcat/Km)/(kuncat).

Additional Considerations of Second-shell Contributions to the Phosphoryl Transfer Step

Interaction Network Involving the Second Coordination Shell Controls Active Site Conformational Heterogeneity

One defining feature of naturally evolved enzymes is the extensive interaction network that connects the substrate, active site residues and the second coordination shell.28,91 Through such interconnected hydrogen-bonding or non-polar interactions, the second-shell residues help precisely position first-shell residues to maximize stabilization of the TS or key intermediates.28,35,36 The importance of an interaction network involving the second-shell residues is observed even in enzymes that catalyze radical chemistry, in which the reactive centers do not exhibit any major change in charge distributions.45,46 For instance, in the vitamin B12 enzymes, the homolytic bond cleavage is stabilized by the interaction between the polar leaving group and charged residue(s) in the second-shell45. In the example of AP, two aspartates on each side of R166 help to position its sidechain to optimally stabilize the non-bridging O1 and O2 in the phosphoryl transfer TS through simultaneous hydrogen-bonding interactions.91 In the WT PafA, similar features are well illustrated by the positions of catalytically critical residues with the hydrogen-bonding network of several second-shell residues and the bi-metallic zinc motif, which help jointly stabilize the substrate, especially in the TS (Fig. 2). Non-polar residues, such as A302, also help position K162 for substrate stablization.

In addition to the average position, the flexibility, or conformational heterogeneity, of first-shell residues can also be important to the chemical step in enzymes; too low flexibility limits the ability of a residue to adjust its position to stabilize the TS or key intermediate,92 especially for residues implicated in multiple catalytic steps,35 while too high flexibility likely leads to a large reorganization energy or unproductive conformations, thus also being detrimental to catalysis.5,22 Relevant questions are whether the conformational distributions of first-shell residues are fine-tuned in naturally evolved enzymes and to what degree the chemical steps are sensitive to the widths of the distribution. An experimental approach to answer such questions is to combine functional studies with structural techniques to probe the relevant conformational ensembles, such as room temperature crystallography and NMR spectroscopy35,36 in highly efficient enzymes.

In our computational study, we observe that the hydrogen-bonding network provided by the second-shell residues (e.g., Y112 and D163) controls the conformational distribution of first-shell residues (both K162 and R164) in the GS. In several second-shell mutants, the conformational heterogeneities of K162 and R164 become broader (Fig. 2), although their dominant positions remain unaltered, which only leads to a modest impact on the phosphoryl transfer barrier height. Therefore, our analysis makes it clear that second-shell residues help ensure that the reactive conformers of the catalytic residues are the most populated,14,22,23 while the barrier for the chemical step (at least the phosphoryl transfer step studied here) is not highly sensitive to the degree of conformational heterogeneity. With the simplest model, the apparent rate constant for the chemical step depends only linearly on the population of the most reactive conformation, thus even reducing the latter by a factor of 2 only leads to a change of ln2 = 0.7 kBT in the free energy barrier. As an alternative description, broadening the conformational distributions of first-shell residues in the mutant GS increases the entropic stabilization of the GS relative to the TS, while the first-shell residues have stronger interactions with the reactive groups and thus exhibit tighter conformational distributions in the TS (e.g., Fig. 2). This explains the modest increase of the free energy barrier for some second-shell mutants (e.g, Y112V/D163V) despite minimal perturbation in the phosphoryl transfer TS.

Second-shell Residues Modulate Active Site Hydration

The physical properties and behaviors of water in the enzyme active sites can be distinct from those in the bulk and may make unique contributions to catalytic efficiency.5,93–95 It is often argued that a low level of active site hydration is desired for efficient catalysis due to lower reorganization energy relative to bulk solution.5,96,97 However, both AP and PafA are highly efficient enzymes despite their solvent-accessible active sites. Our analysis of PafA variants clearly indicates that the hydration level of the active site can be tuned by second-shell mutations (e.g., A302V and D163V), through a combination of steric effects that modulate the active site volume and modification of local hydrophobicity (Figs. 3, S8). Accordingly, the change of hydration level has a visible impact on the exergonicity of the phosphoryl transfer reaction (Fig. S3). It is also intriguing that the key characteristics of the TS are essentially invariant to second-shell mutations, including those that even involve the change of a net charge (D163V and the Y112V/D163V double mutant). These results are attributed to the observation that penetrated water molecules provide alternative stabilization of the leaving group when some interactions are (transiently) broken.

Along this line, we note that all solvent molecules are treated at the MM level in the current study, so as to compare all enzyme variants in a consistent fashion. Alternatively, it is possible to treat the active site water at the QM level in an adaptive QM/MM framework.98,99 However, as discussed in previous work,99 adaptive QM/MM methodologies may also suffer from boundary artifacts when the QM and MM models describe water molecules rather differently.100 On the other hand, the insensitivity of key TS characters to many second-shell mutations studied here is also confirmed by the QM cluster model (Table S1), and thus not limited by any inaccuracy associated with the QM/MM boundary.

In particular for A302V, while MM MD simulations do not reveal any major conformational rearrangements in the GS (Figs. S10, S11), QM/MM simulations show that A302V is the only second-shell variant studied here that exhibits non-negligible perturbation in the TS, especially in the Zn-Olg distribution (Fig. 2c), due to the elevated hydration level in the active site (Fig. S8). The observed TS perturbation is qualitatively consistent with experimental data for A302V: the measured (all experimental data were reported as 2 based logarithm values for the ratio of WT and mutant properties40,44) decrease in kcat/Km (−4.4) is close to the increases in TSA Kd values (~5 for both vanadate and tungstate), while the Kd of Pi is modestly affected (~0.4), suggesting that catalysis in A302V exhibits considerable perturbation in the chemical step. Additionally, the computed PMFs for the phosphoryl transfer step exhibit considerably larger statistical variations as compared to the other mutants (see Fig. S3), again highlighting the stronger perturbation on the phosphoryl transfer step by the A302V mutation, in qualitative agreement with the experimental data discussed above. The treatment of active site solvent at the MM level may overestimate the compensation effect of water for the outer zinc ion stablization (as reflected by the peak at the longer Zn-Olg distance in the TS, see Fig. 2c) as well, which might explain the observation that the average free energy barrier from DFTB3/MM simulations for A302V does not differ significantly from the WT (Table 1).

Implications to Enzyme Design

As discussed in Introduction, distal residues have been observed to contribute significantly to the catalytic properties of designed enzymes improved by directed evolution,30,31 structural informatics-based,101 machine learning-based,37,102,103 or sequence-based approaches.11,15,104,105 Therefore, it is evident that focusing merely on the optimization of first coordination shell, as commonly done in computational enzyme design,28,37,106 is not sufficient. However, since how such distal mutations contribute to the targeted catalytic properties of engineered enzymes is often unknown, it has remained difficult, if not impossible, to predict the identity and location of non-active-site residues that have beneficial effects on the desired catalytic properties. This represents a significant limitation to rational enzyme design. For example, without a decent starting point for engineering, relying on random saturation mutagenesis and/or directed evolution to improve catalytic properties remains costly and time consuming;37 these approaches also require a high-throughput readout or a means to effect a strong selective pressure during evolution. Accordingly, novel experimental and computational approaches have recently emerged to help identify regions that are tightly coupled to activities in the active site.17,32,33 Nevertheless, mutational effects, especially distal ones in the context of exploring new chemical transformations, are still hard to predict. Alternatively, more specific site-directed mutagenesis requires in-depth structural and mechanistic understanding. Following the dissection of second-shell residues’ contributions to catalysis in a highly efficient enzyme like PafA, we are able to highlight several strategies for effective design of enzymes with targeted catalytic properties involving these residues (Fig. 5) that are complementary to other approaches in the literature.

Figure 5: A schematic showing several strategies that may further improve the effectiveness of rational enzyme design by going beyond the first coordination shell.

(i) Assemble catalytic units consisting of hydrogen-bonded or non-polar groups in the first- (blue and green) and second-shells (pink) of the substrate (or a TS analog) to ensure the pre-organized nature of the active site; (ii) Balance the binding affinities of substrates or TS analogs ensembles (indicated with dashed lines); (iii) Explicitly tune the hydration level (blue triangles indicate water molecules) and water properties in the active site; (iv) Incorporate metal binding site (orange) in the second-shell to enhance co-operative hydrogen-bonding interactions to better stabilize reactive groups.

Foremost, it is beneficial to assemble “catalytic units”91 consisting of hydrogen-bonded or non-polar groups to surround the substrate (or a TSA), such that the pre-organized nature of the active site is explicitly established for both transition state stabilization and substrate binding; the requirement of accommodating such catalytic units107 may put more constraints on the appropriate protein scaffold used for the design. Placing first- and second-shell residues together as pre-assembled catalytic units also helps ensure that the most reactive conformation(s) of key catalytic groups constitute the dominant population, which can be verified by molecular dynamics simulations that explicitly probe the relevant conformational landscapes of residues at the active site and nearby, including potential “high energy” conformers of backbones required to accommodate specific sidechain conformers of catalytic residues.14 Along this line, the comparison of K162/R164 distributions in the single (Y112V, D163V) and double (Y112V/D163V) mutants demonstrates that the effects of second-shell residues are not simply additive91 and that a group of hydrogen-bonded residues is more effective in organizing catalytic motifs than individual residues alone.

Most enzyme design protocols do not consider hydration explicitly and treat electrostatic interactions using rather approximate schemes (e.g., distance dependent dielectrics). Our analysis of PafA and related enzymes62,108 suggests that explicitly predicting and optimizing active site hydration level and water-mediated hydrogen-bonding networks using efficient computational tools109–112 should be an integral part of rational enzyme design. Indeed, by controlling the hydration level of the active site and dielectric properties of these confined water,93,94 it is possible to take advantage of the non-additivity of hydrogen-bonding interactions,113 which enables second-shell residues to polarize first-shell residues and enhance the stabilization of reactive moieties. For instance, one strategy is to place divalent metal ions such as Mg2+to modulate active site reactivities through electrostatics,91 and/or metal-ligand mediated interactions. Recent studies highlighted that local hydrophobicity114 and hydrophobic protein-ligand interactions115–117 depend sensitively on the molecular context and are not merely functions of sidechain non-polarity, thus leaving rich opportunities for refined engineering at the molecular level.

Finally, our discussion of binding affinities of different PafA substrates (mono- and diesters) and inhibitors/analogs underscores the importance of strategically positioning catalytic units to balance the binding affinities of cognate and promiscuous ligands (and models for the corresponding transition states), the product and possible inhibitors, so that catalytic properties such as substrate scope, chemical specificity and product inhibition can be modulated as well. In other words, instead of focusing on the binding affinity of a single type of TSA, as commonly done, balancing binding properties of an ensemble of related species is preferred.118 Indeed, the power of enzymes relies on preferential stabilization of the TS(s) over the ground state and inhibitors, and allowing a modest level of catalytic promiscuity offers the opportunity to further evolve novel catalytic activities.119–123

Conclusion

In this work, we focus on several second-shell residues in PafA, a representative system for highly efficient enzymes, to understand their notable contributions to different aspects of catalysis observed in recent high-throughput experiments. By adopting a multi-faceted approach that integrates QM/MM free energy computations, molecular mechanical molecular dynamics simulations and DFT cluster model calculations, we probe the rate-limiting phosphoryl transfer step and structural properties of all relevant enzyme states. In combination with available experimental data, our computational results show that mutations of studied second-shell residues impact catalytic efficiency mainly by perturbing the apo state and therefore substrate binding, while they do not alter the nature of phosphoryl transfer transition state significantly. The manifestation of the positioning effect of second-shell residues mainly in the apo state, rather than the ground state or transition state likely applies more broadly to enzymes that feature strong electrostatic interactions between the charged substrate and the first coordination shell. Several mutations also perturb the active site hydration level, which in turn influences the energetics of phosphoryl transfer. Evidently, second-shell residues are able to modulate active site hydration and therefore electrostatic properties through a combination of steric effects and modification of local hydrophobicity. Overall, our study provides mechanistic insights into the contributions of second-shell residues in a highly optimized enzyme during evolution. These mechanistic insights also highlight the importance of going beyond the first coordination shell to consider pre-organization of the active site and balance the corresponding conformational ensembles for both transition state stabilization and substrate binding, as well as explicitly predicting active site hydration level for more efficient enzyme design and engineering.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the NIH Grant R35-GM141930. Computational resources from the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment(XSEDE124), which is supported by NSF Grant ACI-1548562, are greatly appreciated; part of the computational work was performed on the Shared Computing Cluster which is administered by Boston University’s Research Computing Services (URL: www.bu.edu/tech/support/research/). We acknowledge discussion with Professor K. Allen and her comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Results from QM cluster models, additional results from QM/MM simulations of all relevant enzyme states, and results from molecular mechanical MD simulations of the ground and apo states are included.

References

- (1).Wolfenden R; Snider MJ The depth of chemical time and the power of enzymes as catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res 2001, 34, 938–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Jencks WP Catalysis in chemistry and enzymology; Dover publications: New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Fersht A Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science: A Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding; W.H. Freeman and Company, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zalatan JG; Herschlag D The far reaches of enzymology. Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 516–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Warshel A; Sharma PK; Kato M; Xiang Y; Liu HB; Olsson MHM Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis. Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 3210–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Garcia-Viloca M; Gao J; Karplus M; Truhlar DG How enzymes work: Analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations. Science 2004, 303, 186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Aqvist J; Kazemi M; Isaksen GV; Brandsdal BO Entropy and Enzyme Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50, 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Arcus VL; Mulholland AJ Temperature, Dynamics, and Enzyme-Catalyzed Reaction Rates. Annu. Rev. Biophys 2020, 49, 163–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lee J; Goodey NM Catalytic Contributions from Remote Regions of Enzyme Structure. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 7595–7624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Currin A; Swainston N; Day PJ; Kell DB Synthetic biology for the directed evolution of protein biocatalysts: Navigating sequence space intelligently. Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44, 1172–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Rix G; Watkins-Dulaney EJ; Almhjell PJ; Boville CE; Arnold FH; Liu CC Scalable, continuous evolution for the generation of diverse enzyme variants encompassing promiscuous activities. Nat. Comm 2020, 11, 5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wrenbeck EE; Azouz LR; Whitehead TA Single-mutation fitness landscapes for an enzyme on multiple substrates reveal specificity is globally encoded. Nat. Comm 2016, 8, 15695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Jimenez-Oses G; Osuna S; Gao X; Sawaya MR; Gilson L; Collier SJ; Huisman GW; Yeates TO; Houk KN The role of distant mutations and allosteric regulation on LovD active site dynamics. Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10, 431–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Otten R; Padua RAP; Bunzel HA; Nguyen VY; Pitsawong W; Patterson M; Sui S; Perry S; Cohen AE; Hilvert D; Kern D How directed evolution reshapes the energy landscape in an enzyme to boost catalysis. Science 2020, 370, 1442–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Neugebauer ME; Kissman EN; Marchand JA; Pelton JG; Sambold NA; Millar DC; Chang MCY Reaction pathway engineering converts a radical hydroxylase into a halogenase. Nat. Chem. Biol 2021, 18, 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Xie WJ; Asadi M; Warshel A Enhancing computational enzyme design by a maximum entropy strategy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2022, 119, e2122355119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Osuna S The challenge of predicting distal active site mutations in computational enzyme design. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci 2021, 11, e1502. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Damry AM; Jackson CJ The evolution and engineering of enzyme activity through tuning conformational landscapes. Prot. Eng. & Select 2021, 34, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Cameron CE; Benkovic SJ Evidence for a functional role of the dynamics of glycine-121 of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase obtained from kinetic analysis of a site-directed mutant. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 15792–15800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Benkovic SJ; Hammes-Schiffer S A perspective on enzyme catalysis. Science 2003, 301, 1196–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Singh P; Vandemeulebroucke A; Li JY; Schulenburg C; Fortunato G; Kohen A; Hilvert D; Cheatum CM Evolution of the Chemical Step in Enzyme Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 6726–6732. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Campbell E; Kaltenbach M; Correy GJ; Carr PD; Porebski BT; Livingstone EK; Afriat-Jurnou L; Buckle AM; Weik M; Hollfelder F; Tokuriki N; Jackson CJ The role of protein dynamics in the evolution of new enzyme function. Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12, 944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hong NS et al. The evolution of multiple active site configurations in a designed enzyme. Nat. Comm 2018, 9, 3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Crean RM; Gardner JM; Kamerlin SCL Harnessing Conformational Plasticity to Generate Designer Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 11324–11342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Romero-Rivera A; Garcia-Borras M; Osuna S Role of Conformational Dynamics in the Evolution of Retro-Aldolase Activity. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 8524–8532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Maria-Solano MA; Iglesias-Fernandez J; Osuna S Deciphering the Allosterically Driven Conformational Ensemble in Tryptophan Synthase Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 13049–13056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Tomatis PE; Rasia RM; Segovia L; Vila AJ Mimicking natural evolution in metallo-β-lactamases through second-shell ligand mutations. Proc. Acad. Natl. Sci. U.S.A 2005, 102, 13761–13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Bunzel HA; Anderson JLR; Mulholland AJ Designing better enzymes: Insights from directed evolution. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2021, 67, 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Fisher G; Corbella M; Alphey MS; Nicholson J; Read BJ; Kamerlin SCL; da Silva RG, Allosteric rescue of catalytically impaired ATP phosphoribosyltransferase variants links protein dynamics to active-site electrostatic preorganisation. Nat. Comm 2022, 13, 7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Zeymer C; Hilvert D Directed Evolution of Protein Catalysts. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2018, 87, 131–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Chen K; Arnold FH Engineering new catalytic activities in enzymes. Nat. Catal 2020, 3, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Bhattacharya S; Margheritis EG; Takahash K; Kulesha A; D’Souza A,; Kim I; Yoon JH; Tame JRH; Volkov AN; Makhlynets OV; Korendovych IV NMR-guided directed evolution. Nature 2022, 610, 389–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Modi T; Risso VA; Martinez-Rodriguez S; Gavira JA; Mebrat MD; Van Horn WD,; Sanchez-Ruiz JM; Ozkan SB Hinge-shift mechanism as a protein design principle for the evolution of β-lactamases from substrate promiscuity to specificity. Nat. Comm 2021, 12, 1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Mazmanian K; Sargsyan K; Lim C How the Local Environment of Functional Sites Regulates Protein Function. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 9861–9871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Yabukarski F; Biel JT; Pinney MM; Doukov T; Powers AS; Fraser JS; Herschlag D Assessment of enzyme active site positioning and tests of catalytic mechanisms through X-ray–derived conformational ensembles. Proc. Acad. Natl. Sci. U.S.A 2020, 117, 33204–33215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Yabukarski F; Doukov T; Pinney MM; Biel JT; Fraser JS; Herschlag D Ensemble-function relationships to dissect mechanisms of enzyme catalysis. Sci. Adv 2022, 8, eabn7738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lovelock SL; Crawshaw R; Basler S; Levy C; Baker D; Hilvert D; Green AP The road to fully programmable protein catalysis. Nature 2022, 606, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Diez-Roux G; Ballabio A Sulfatases and human diseases. Annu. Rev. Genom. Human Gene 2005, 6, 355–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Nussinov R; Tsai CJ Allostery in Disease and in Drug Discovery. Cell 2013, 153, 293–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Markin CJ; Mokhtari DA; Sunden F; Appel MJ; Akiva E; Longwell SA; Sabatti C; Herschlag D; Fordyce PM Revealing enzyme functional architecture via high-throughput microfluidic enzyme kinetics. Science 2021, 373, eabf8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Sunden F; AlSadhan I; Lyubimov AY; Ressl S; Weiersma-Koch H; Borland J; Brown CL Jr.; Johnson TA; Singh Z; Herschlag D Mechanistic and Evolutionary Insights from Comparative Enzymology of Phosphomonoesterases and Phosphodiesterases across the Alkaline Phosphatase Superfamily. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 14273–14287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sunden F; AlSadhan I; Lyubimov A; Doukov T; Swan J; Herschlag D Differential catalytic promiscuity of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily bimetallo core reveals mechanistic features underlying enzyme evolution. J. Biol. Chem 2017, 292, 20960–20974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lassila JK; Zalatan JG; Herschlag D Biological phosphoryl transfer reactions: Understanding mechanism and catalysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2011, 80, 669–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Markin CJ; Mojhtari DA; Du S; Doukov T; Sunden F; Fordyce PM; Herschlag D High-throughput enzymology reveals mutations throughout a phosphatase that decouple catalysis and transition state analog affinity. bioRxiv 2022-November-08, doi: 10.1101/2022.11.07.515533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Sharma PK; Chu ZT; Olsson MHM; Warshel A A new paradigm for electrostatic catalysis of radical reactions in vitamin B12 enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad.Sci. U.S.A 2007, 104, 9661–9666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Roman-Melendez GD; von Glehn P,; Harvey JN; Mulholland AJ; Marsh ENG Role of Active Site Residues in Promoting Cobalt-Carbon Bond Homolysis in Adenosylcobalamin-Dependent Mutases Revealed through Experiment and Computation. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Roston D; Kohen A; Doron D; Major DT Simulations of Remote Mutants of Dihydrofolate Reductase Reveal the Nature of a Network of Residues Coupled to Hydride Transfer. J. Comput. Chem 2014, 35, 1411–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Fan Y; Cembran A; Ma SH; Gao JL Connecting Protein Conformational Dynamics with Catalytic Function As Illustrated in Dihydrofolate Reductase. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 2036–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Hammes-Schiffer S; Watney JB Hydride transfer catalysed by Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis dihydrofolate reductase: coupled motions and distal mutations. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2006, 361, 1365–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Saen-Oon S; Ghanem M; Schramm VL; Schwartz SD Remote mutations and active site dynamics correlate with catalytic properties of purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biophys. J 2008, 94, 4078–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]