Abstract

Vacant urban land, although not officially designated as a green space, often exhibits a semi-wild natural state due to being left open to colonization by nature. Attention to the effects of vacant urban land on human health has increased due to both rising urban vacancy rates and non-communicable diseases (NCDs). However, relationships between many vacant land characteristics (such as vegetation coverage, size, duration, and location) and NCDs have not been comprehensively examined, especially comparing shrinking (depopulating) and growing (populating) cities. This study evaluates St. Louis, MO (shrinking), and Los Angeles, CA (growing) to explore these relationships using ordinary least squares (OLS) interaction analysis with a moderator approach. Results show that associations between vacancy rate, duration, location, and NCDs differ significantly between city types. Vegetation coverage and size are associated with specific NCDs, but there are no differences between city types. Unlike the largely dilapidated vacant lands in the shrinking city, which tend to harm public health, vacant lots in the growing city were more functional green spaces that can, in some cases, even mitigate NCDs. Interestingly, In St. Louis, the shorter the average duration of the vacant land, the greater the risk of NCDs in a shrinking city. This is because vacant land can be contagious to nearby lots if not treated, leading to more newly emerged vacant lands and reducing the average duration of vacant land. In such cases, census tracts with the lower duration of vacant lands in St. Louis tend to be areas facing persistent environmental degradation and high public health threats. Regarding location, vacant lands near industrial areas were linked to negative health outcomes in the Los Angeles (growing), while those near single-family and commercial areas posed higher risks of NCDs in the St Louis (shrinking). The findings aid decision-making for land supply regulation and regeneration as well as urban green space management to promote human health and well-being.

Keywords: Non-communicable diseases, Regeneration, Urban green space management, Vacant land characteristics

1. Introduction

With the current growth in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) - currently accounting for 63% of the total deaths globally (Su et al., 2016) - increased attention has been given to understanding the effects of the urban environment on human health, with particular emphasis placed on green spaces, areas of grass, trees, or other vegetation set apart for recreational or aesthetic purposes in urban environments. Green spaces have been found to promote physical and mental well-being. They offer opportunities for physical activity and contact with nature, which can reduce stress and improve various health outcomes (Hunter et al., 2019, Sivak et al., 2021). However, most research on green spaces has focused on greenness rather than quality. It is also important to consider the negative health effects of poor-quality green spaces, such as vacant urban land (Sivak et al., 2021).

Vacant urban land refers to undeveloped or abandoned land with overgrown vegetation, abandoned structures, the dumping of waste, or other illegal activities (Su et al., 2016). Such lands can often be considered a form of low-quality open space or green space, as they typically exhibit a semi-wild natural state and lack the design, management, and amenities of purpose-built green spaces such as parks and gardens (Kim et al., 2018, Lee and Newman, 2019, Sivak et al., 2021). Among studies related to vacant land and humans, negative relationships between vacant land and public health have predominately been found and the repurposing of vacant lots has shown the opposite effect (Branas et al., 2018). South et al. (2015) found that being in close vicinity to a re-greened vacant lot lowers heart rates compared to being in close proximity to a non-greened vacant lot. Taggert et al. (2019) demonstrated that higher amounts of children with elevated levels of lead in their blood primarily lived in neighborhoods with an abundance of vacant lots compared to neighborhoods with lower vacancy rates. Although the negative associations between the amount of vacant urban lands and health outcomes have been somewhat established, few studies have comprehensively evaluated the relationship between specific vacant land characteristics and individual public health outcomes, especially NCDs.

Considering the aforementioned associations, the physical characteristics of vacant lands, such as vegetation coverage, size, and duration of vacancy, should be determinants of public health conditions. For example, vacant lands with dense vegetation can provide hiding places for criminal activities and often accumulate pollutants mainly from illegal dumping (Potgieter et al., 2019). Vacant lands with more flora, on the other hand, can attract mosquito populations that transmit disease causing insects such as mosquitoes caring West Nile Virus (WNV) than others (Sivak et al., 2021). Further, some vegetation species typically found on unkempt vacant lots (such as Ragweed, Dalbergia spp) can produce increases in allergic responses to humans within their environment (Nowak & Ogren, 2021). Inversely, properly vegetated vacant serves as green space which promotes less negative health consequences (Hunter et al., 2019).

The size of a given vacant land or set of vacant lands may affect people's perception of vacant spaces because object size perception often guides human behavior and decisions (Kristensen et al., 2021). Large plots of land tend to stand out in urban areas where land is at a premium and most available space is already built upon. In contrast, smaller vacant plots may be more easily overlooked, especially if they are located in areas that are already densely populated or have a high concentration of buildings. Small vacant plots may blend in with their surroundings, and residents may not realize that the land is vacant or available for use. Relatedly, the duration of vacant land, or how long a lot remains vacant over time, may also be associated with worsening public health condition in that the longer a lot remains vacant, the worse public health conditions could progress. Long-term vacant land can become a chronic stressor, accelerating the health problems that are often associated with excessive vacant land amounts (Frakt, 2018, Martínez-García et al., 2018, Newman et al., 2018, Palmer et al., 2019). Wang & Immergluck (2018) confirmed that long-term neighborhood house vacancies (houses that are vacant for 6 months or longer) are closely connected with worsening human health outcomes.

The spatial distribution of vacant land, which can play a significant role in public health (Lis et al., 2019), has been rarely incorporated in the current literature related to human health and the built environment. Vacant lands that are closer to industrial land uses have a higher chance of airborne pollutants deposition and increase soil concentrations of neurotoxins such as mercury (Nassauer & Raskin, 2014). Additionally, prior research indicates that non-residential land uses, such as concentrations of inactive commercial areas, can sometimes provide a “target rich” environment for criminals. If vacant lands are located near high crime areas, such as bus stops, schools, retails, and bars, they often encourage more offenders and crime incidents (Nassauer & Raskin, 2014). Non-maintained vegetation on vacant lots that obstructs sight can provide also increase crime and result in increased areas deemed as dangerous to the public (Lis et al., 2019). Vacant lands closer to residential areas have also been shown to be more likely to result in daily exposure to increased chronic stress (Su et al., 2016). Noise, vandalism, public drinking, illegal dumping, drug use, and other behaviors have all been linked to these areas, which can then lead to the decreased physical and mental health of residents (Sampson et al., 2017).

It is also currently unclear whether vacant land in shrinking (excessively depopulating) or growing (populating) cities perform differently in terms of their impacts on health outcomes. The Shrinking Cities International Research Network (SCIRN) defines a shrinking city as a densely populated urban area (10,000 population minimum) has lost notable population for more than two years and is experiencing some form of economic downturn (Hollander & Németh, 2011). On the contrary, a growing city is a city with growing urban population and economy (Devas & Rakodi, 1993). Since the cause, quantity, and type of vacant land in shrinking and growing cities tend to differ (Lee et al., 2018), current research should assess, much more deeply, these conditions and how they are linked to public health.

In the most recent national survey to US cities, Newman et al. (2016) found that, on average, each U.S. city is comprised of 16.7% vacant land. It was also found that the average vacant land to the total land ratio in cities in the Midwest and South is about double that of cities in the West and Northeast (Newman et al., 2016). The areas that experienced decentralization and deindustrialization in shrinking cities over the past few decades have more vacant lands than others (Newman et al., 2018). Vacant land in growing cities may be caused largely by large-scale annexation and often appear on the outskirts of the city, while vacant lands in shrinking cities may be the result of depopulation and economic downturn (Lee et al., 2018, Song et al., 2020). Thus, unlike shrinking cities, where there are often more dilapidated, abandoned, or high polluted vacant lands, the majority of vacant lands in growing cities are considered greenfield sites which are ripe for future development (Newman et al., 2018, Sivak et al., 2021).

2. Research Objectives

This study provides valuable insights for planners and decision-makers in 1) understanding the attributes of vacant land that have the strongest association with human health outcomes, 2) developing vacant land regeneration strategies for different urban scenarios, and 3) prioritizing high-risk areas for prevention and intervention policy development. To guide this investigation, we posit the following research questions and hypotheses:

What vacant land characteristics (physical and geographic conditions) are associated with public health outcomes?

Hypothesis.

Higher vacancy rates, larger vacant land size, and longer duration of vacancy, and vacant land proximity to high density residential, commercial and industrial are positively associated with a higher prevalence of NCDs.

-

(2)

Do associations in the relationship between vacant land characteristics and public health outcomes differ between shrinking and growing cities?

Hypothesis.

Vacant lands in shrinking cities have stronger associations with negative health outcomes, while vacant lands in growing cities present more opportunities for positive health outcomes.

3. Methods

3.1. Study areas

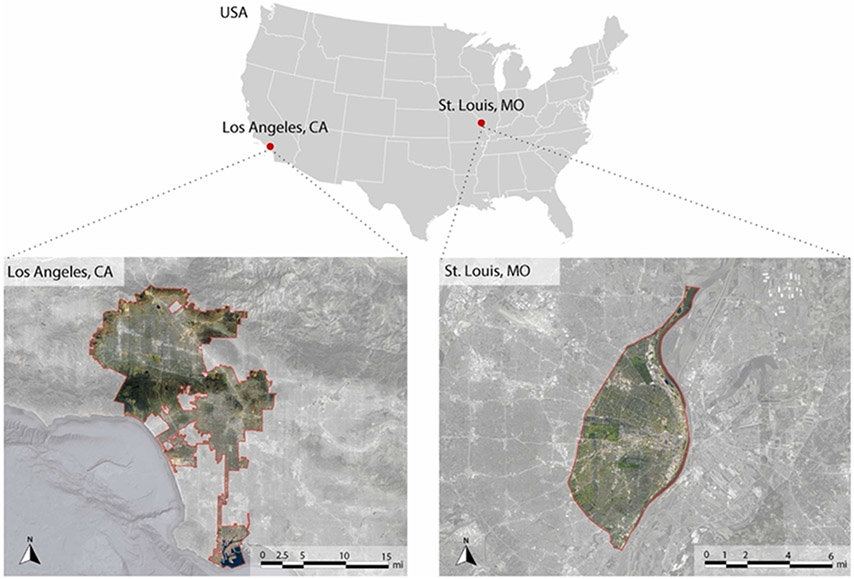

To address the aforementioned research gaps, we aim to compare associations between vacant land characteristics and health outcomes between shrinking and growing cities, using St. Louis, MO (shrinking city) and Los Angeles, CA (growing city) as representative U.S.-based examples. St. Louis is located in the central part of the United States, covering an urban area of approximately 61.72 square miles with 2156,323 urban population, while Los Angeles is situated in the western part, encompassing a larger urban area of around 469.49 square miles with 12,237,376 urban population (Wikipedia, 2023a, Wikipedia, 2023b) (see Fig. 1). Both cities have large urban areas and significant levels of urbanization, making them suitable for comparative analysis. In terms of environmental characteristics, St. Louis experiences a humid continental climate, with hot summers and cold winters, while Los Angeles has a Mediterranean climate, characterized by mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. However, despite these climate differences, both cities experience a range of temperatures throughout the year that fall within a similar range, with St. Louis averaging about 56.9°F, and Los Angeles averaging about 65.4°F (NOAA, 2023).

Fig. 1.

Geographic location of Los Angeles and St. Louis.

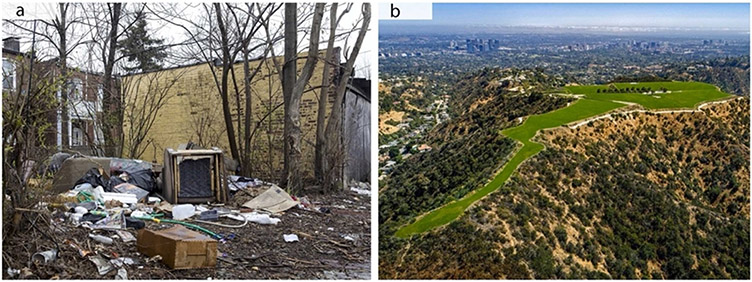

Fig. 2 provides photographs of typical examples of vacant lands from each study area (Fig. 2a: St. Louis; Fig. 2b: Los Angeles). These visual representations offer insights into the physical attributes of vacant lands, showcasing the vacant and underutilized spaces within the urban fabric of these cities. By comparing these two cities, we aim to gain a comprehensive understanding of the relationships between vacant land characteristics and health outcomes in diverse urban contexts.

Fig. 2.

Vacant land examples from each study area (Fig. 2a: vacant land with Furniture and other trash are dumped in St. Louis (Hidalgo, 2018); Fig. 2b: a 157-acre land has never been developed in Los Angeles (Coller, 2022)).

3.2. Constructs and variables

This study explores the associations between the characteristics of vacant urban land and NCDs in shrinking and growing cities at the census tract level. We selected a shrinking and a growing city with populations of more than 10,000 for comparison, St. Louis, MO (shrinking), and Los Angeles, CA (growing), to conduct this research. The city of St. Louis has lost 64% of its residents since 1950 (Zhu & Newman, 2021). In 2021, the population of St. Louis dipped below 300,000, and the metropolitan area also suffered a population loss as the region reported more deaths than births for the first time (Barker, 2022). According to 2020 census data, Los Angeles, on the contrary, is one of the fastest-growing cities in California, with 106,126 population increase compared to a decade ago (Ludwig, 2021).

The data on NCDs was acquired from the 2021 PLACES dataset (CDC, 2021). The 2021 PLACES data estimates 13 health outcomes, including mental health, physical health, cancer, coronary heart disease (CHD), diabetes, asthma, all teeth lost, arthritis, high blood pressure, stroke, high cholesterol, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and chronic kidney disease for areas across the United States using the small area estimation method based on CDC’s 2019 BRFSS (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System) survey data (CDC, 2021). The CDC’s 2019 BRFSS’s health outcomes were measured by dividing respondents aged 18 years and order who report that they had health issues by the total number of respondents. To explore the neighborhood-level (census tracts are assumed as neighborhood boundaries) association between vacant urban land features and NCDs, we pooled estimates of health outcomes at the census tract level (for all health outcomes) (see Figures 3.1 & 3.2). We excluded the tooth loss data from the study because it is an extreme case where only 17.3% of people aged 65 years and older have no remaining teeth (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, 2022).

Based on the previous literature, this study includes characteristics of vacant urban land such as physical condition (vacancy rate, vacant land coverage, the average vacancy size, vacancy duration), and vacant land geographic condition (closest distance to single-family, multi-family, commercial, and industrial areas) (Newman et al., 2018, Nassauer and Raskin, 2014). All vacant land characteristics were aggregated to the census tract level to match the geographic scale of the PLACES health outcomes data (see Figure 3.3 & 3.4). Vacant land parcel data from 2010 to 2019 for St. Louis and Los Angeles were retrieved from their respective city governments (City of St. Louis, MO Open Data, 2022, County of Los Angeles, 2022), which include vacant property information (area, land use, and geographic location). The vacant land for both cities is defined as “land that is not being used or occupied for any purpose, with or without buildings (City of St. Louis, MO Open Data, 2022, County of Los Angeles, 2022).” Agricultural vacant lands were excluded from this study because they are usually located in sparsely populated areas and close to other agricultural land.

Vacant area was calculated as the percentage of vacant parcel acreage of the total acreage per census tract. Average vacant land size was calculated by averaging the size of vacant lots per census tract. Vacant lots that remained vacant through the entire study period, or continuous, and those that were in contact with one another, or adjacent, are considered a single vacant lot. Based on historical vacant land parcel data from 2010 to 2019, we determined the vacancy duration for each parcel. Vacant land transitioning into other land uses was determined by the distance between each vacant lot and the nearest single-family, multi-family, commercial, and industrial area using proximity analysis from ArcGIS Pro 3.0.3. We used closest distance to nearest land use instead of the actual land use of the vacant land because the surrounding land use of the vacant land was not always necessarily the same as the land use of the transitioned vacant land.

The vegetation coverage conditions of vacant land during periods of time when tree or shrub species have leaves were assessed using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) derived from the National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP). NAIP is the fine-grain (1 m resolution) imagery that can capture vegetation status in small urban parcels (Smith, 2021). We included green space percentage per census tract as an independent variable to help indicate how high-quality the existing green space is (typically, vacant land is low-quality, unkempt green space), as high-quality green space has been linked to the overall well-being of residents (Rojas-Rueda et al., 2019). Greenspace percentage, in this study, was calculated as the proportion of each census tract covered by federal/state/municipal parks.

Control variables were obtained from the 2019 American Community Survey 5-year Estimates (see Fig. 3a & 3b). Based on previous studies (Cohen et al., 2003, Wang and Immergluck, 2018), socioeconomic status (poverty, unemployed, housing cost burden, no high school Diploma, no health insurance), household composition (aged 65 or older, female, minority, English language), housing type & transportation (multi-unit structures, mobile homes, crowding, no vehicle, and housing units built before the year of 1970) were included as control variables. Because some of control variables are correlated with each other and too many variables can lead to overfitting, we used percentile ranking method, which is commonly used to create aggregate indexes, such as the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention Social Vulnerability Index (CDC/ATSDR, 2014), to create three summary (theme ranking) variables - socioeconomic status, household composition, and housing type & transportation. We generated each tract’s percentile rank for individual variables and then summed the percentile ranks for the variables comprising each theme. Tracts in the top 10% were given a value of 1 to indicate high vulnerability. Tracts below the 90% percentile were given a value of 0. We also added population density as a control variable since high and low population density are recognized risk factors for a variety of NCDs (Carnegie et al., 2022). Population density is defined as the average land acreage per capita by census tract. Appendix 1 describes all variables used in this study.

Fig. 3.

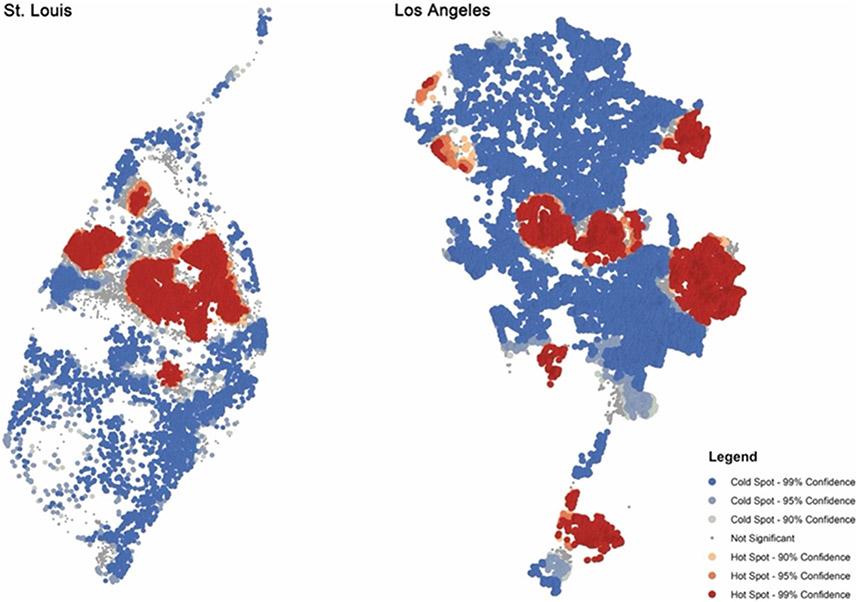

Vacant land hotspot analysis for St. Louis and Los Angeles in 2019.

3.3. Analysis

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative analysis through the examination of geographic data and visual representations of vacant lands and quantitative analysis using an OLS interaction model. Geographic distribution of NCDs, vacant land characteristics, and control variables were mapped using ArcGIS Pro 3.0.3. To explore the geographical distribution of vacant land, hotspot analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*) was conducted to identify statistically significant clustering of vacant land in both cities during 2019 (Mashinini et al., 2020).

For the quantitative analysis, the study utilized ordinary least squares (OLS) interaction analysis with a moderator approach, conducted using the Stata/SE 15.0 software. This approach allowed us to assess the nature of relationships between characteristics of vacant urban land (such as physical conditions and geographic conditions) and NCDs in both shrinking and growing cities. By adopting a moderator framework, we accounted for the influence of city type on the relationships between the independent and dependent variables. The moderator variable determines how the effect of the vacant land characteristics on NCDs may differ based on whether the city is shrinking or growing.

To fully understand the impact of vacant land characteristics on NCDs, we ran separate models for 12 individual NCD values versus the vacant urban land characteristics. The individual NCDs in each model is the outcome variable, characteristics of vacant urban land are the independent variables, and city type is the moderator variable. A total of nine interaction terms were created including eight interaction terms of city type and each vacant characteristics and an interaction term of city type and green space. City type is used as a dummy variable (0 = Los Angeles [growing city]; 1 =St. Louis [shrinking city]). When adding interaction terms into the model, the coefficient for each predictor becomes the coefficient for that variable only for the reference group (Los Angeles) and the interaction term between city type and each predictor represents the difference in the coefficients between the reference group (Los Angeles) and the comparison group (St. Louis). To determine the coefficient for the comparison group (St. Louis), we added the coefficients for the predictor and that predictor’s interaction with the city type. The advantage of incorporating interaction terms is that the p-value for each interaction term provides a significance test for the difference in coefficients (Jaccard & Turrisi, 2003).

Because one hundred percent (106/106) of the census tracts had vacant lands in St. Louis but only 75% (744/993) of the census tracts had vacant lands in Los Angeles, the vacant land characteristic variables had missing values in Los Angeles. These are labeled as structurally missing data because vacant land does not exist. Thus, we excluded census tracts with such missing data in our study. Several assumptions, such as linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, independence, and multicollinearity, are required to apply the OLS interaction analysis. We used difference in beta values (DFBETA) to assess the specific impact of an observation on the regression coefficients in each model and found no major outliers of interest. Both a White’s test and a Breusch-Pagan test were then utilized to test on heteroskedasticity of each model. Both tests showed that model is homogenous. To assess the degree of collinearity, (variance inflation factor (VIF) was used. Results indicated that all variables’ VIF values were smaller than 10, meaning that the variable could be considered as a linear combination of other independent variables. Because vacancy data and green space data were skewed, we performed log transformations of all independent variables to help correct the skewness. We also checked the error terms for each model to confirm that they were normally distributed. After all assumptions were satisfied, we ran separate moderator models for 12 NCD values versus the vacant urban land characteristics.

To test the influence of two sets of independent variables, the interaction analysis methodology was based on a three-model process: Model 1, base model estimation, Model 2, vacant land physical condition estimation, and Model 3, overall model estimation. The base model captured the effect of the vacancy rate and green space rate on NCD’s. After analyzing the vacancy rate and green space rate through the base model, vacant land physical condition independent variables were added to Model 2 to estimate the effect on NCD. Lastly, vacant land geographic condition variables were added in Model 3.

4. Results

4.1. Vacancy rates and spatial distribution

The vacancy rates in St. Louis and Los Angeles exhibited distinct trends over the study period. St. Louis experienced a steady increase in vacancy rate, with an average annual growth rate of 0.09%, whereas Los Angeles showed slight fluctuations but an overall downward trend with an annual decrease of 0.03%. In 2019, St. Louis had a vacancy rate nearly 7% higher than Los Angeles, despite having smaller average vacant land sizes (Table 1 & 2). Hotspot analysis revealed that vacant lands in St. Louis were concentrated in the northern region of the city, characterized by a lower socioeconomic status compared to other areas. In contrast, vacant lands in Los Angeles were concentrated in the middle and periphery of the city, where a relatively higher socioeconomic status prevailed (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

St. Louis vacant land change from 2010 to 2019

| Year | Vacant land area (acre) |

Vacant land area (%) |

Vacant land number |

Vacant land number (%) |

Vacant land mean size (acre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 4882.43 | 16.97% | 19,704 | 15.71% | 0.25 |

| 2011 | 4925.94 | 17.12% | 20,035 | 15.98% | 0.25 |

| 2012 | 4946.29 | 17.19% | 20,256 | 16.15% | 0.24 |

| 2013 | 4956.26 | 17.23% | 20,412 | 16.28% | 0.24 |

| 2014 | 4989.93 | 17.34% | 20,581 | 16.41% | 0.24 |

| 2015 | 5013.54 | 17.43% | 20,801 | 16.59% | 0.24 |

| 2016 | 5032.33 | 17.49% | 20,983 | 16.73% | 0.24 |

| 2017 | 5051.12 | 17.56% | 21,165 | 16.88% | 0.24 |

| 2018 | 5059.83 | 17.59% | 21,428 | 17.09% | 0.24 |

| 2019 | 5111.86 | 17.77% | 21,869 | 17.44% | 0.23 |

Table 2.

Los Angeles vacant land change from 2010 to 2019

| Year | Vacant land area (acre) |

Vacant land area (%) |

Vacant land number |

Vacant land number (%) |

Vacant land mean size (acre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 20770.12 | 10.74% | 21,955 | 3.92% | 0.92 |

| 2011 | 20108.31 | 10.40% | 22,200 | 3.97% | 0.90 |

| 2012 | 19837.35 | 10.26% | 22,355 | 4.00% | 0.90 |

| 2013 | 19578.12 | 10.12% | 22,505 | 4.02% | 0.89 |

| 2014 | 19663.79 | 10.17% | 22,742 | 4.06% | 0.88 |

| 2015 | 19926.04 | 10.30% | 22,946 | 4.10% | 0.86 |

| 2016 | 20112.56 | 10.40% | 23,171 | 4.14% | 0.84 |

| 2017 | 20199.93 | 10.45% | 23,442 | 4.19% | 0.85 |

| 2018 | 20008.54 | 10.35% | 23,721 | 4.24% | 0.85 |

| 2019 | 20190.89 | 10.44% | 24,047 | 4.30% | 0.86 |

4.2. Vacant land characteristics

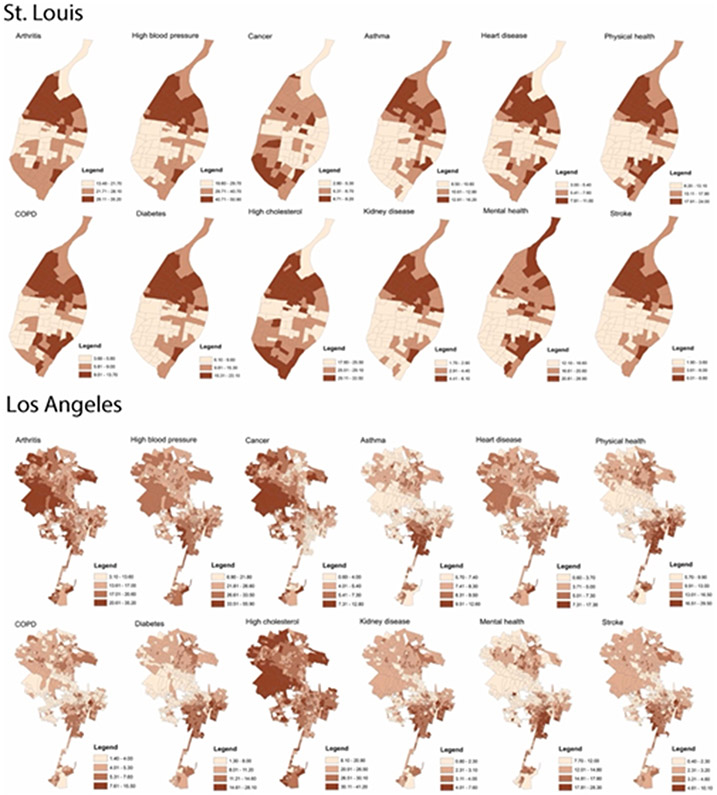

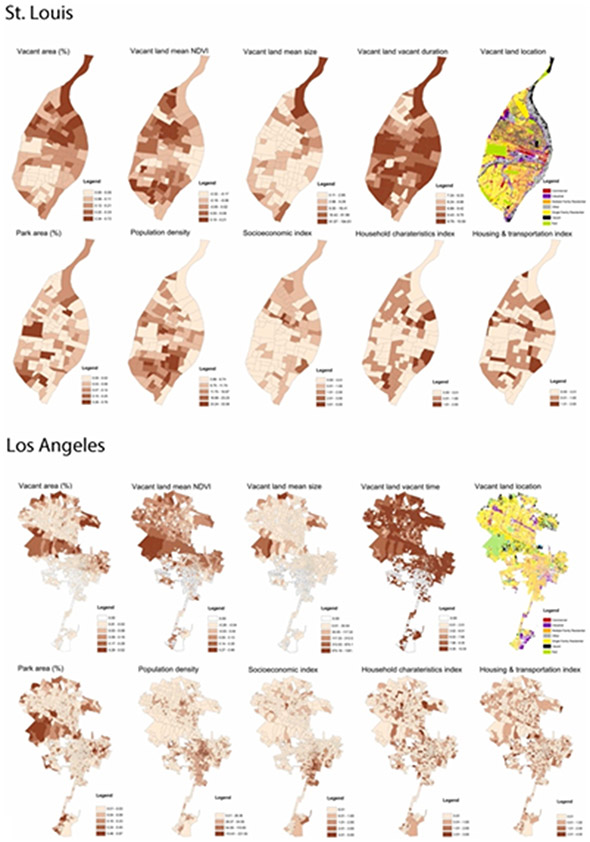

Descriptive statistics (Appendix 2) and spatial distribution analyses (Fig. 4 & 5) provided further insights into the vacant land characteristics in St. Louis and Los Angeles in 2019. St. Louis had an average vacancy rate per census tract that was 14% higher than Los Angeles. The highest vacancy rate within a census tract in St. Louis (72%) exceeded the highest vacancy rate within the top Los Angeles census tract (52%). Moreover, vacant lands in both cities were predominantly characterized by barren lands or abandoned structures, as indicated by the average NDVI values close to 0 (−0.02 for St. Louis; 0.05 for Los Angeles). However, some vacant lands in Los Angeles exhibited higher vegetation quality, as evidenced by a maximum NDVI value of 0.98.

Fig. 4.

Spatial distribution of NCDs for St. Louis and Los Angeles.

Fig. 5.

Vacant land characteristics and social vulnerability distribution for St. Louis and Los Angeles.

The size of vacant lands also showed variations between the inner city and the periphery in both cities. Generally, vacant lands on the periphery were larger than those in the inner city, which was attributed to annexation patterns (Fig. 5). Additionally, the average vacancy duration in St. Louis was 0.49 years longer than in Los Angeles. Most of the newly emerged vacant lands in St. Louis were concentrated in the northern region.

Regarding the geographic location of vacant lands, St. Louis had a higher prevalence of vacant lands in multifamily and industrial areas, whereas Los Angeles exhibited a greater concentration of vacant lands in single-family neighborhoods. Both cities had relatively low green space ratios of approximately 5%, with St. Louis being 2% higher than Los Angeles. Analysis of CDC data revealed that St. Louis exhibited lower overall health, lower population density, and higher social vulnerability compared to Los Angeles. The distribution of NCDs in St. Louis showed higher concentrations in the northern region and the southern border, which aligns with areas characterized by higher socioeconomic vulnerability and vacant land rates. In Los Angeles, NCDs did not exhibit a clear pattern. Arthritis, high blood pressure, cancer, heart disease, high cholesterol, kidney disease, and stroke were scattered throughout the city, while asthma, physical health, COPD, diabetes, and mental health showed greater concentration in the northern and southern regions.

4.3. Vacant land characteristics and NCDs

The interaction analysis demonstrated that Model 3 (Table 3) had the highest explanatory power among the different models, as evidenced by the adjusted R-squared values. The base model (Model 1) for different NCDs explained 19–58% of the variance (see Appendix 2). The models (see Appendix 3) with vacant land physical condition (Model 2) and vacant land geographic condition (Model 3) had higher explanatory power than the base model (Adjusted R2 values are 0.36–0.83 and 0.53–0.84, respectively).

Table 3.

Model 3: comparison of coefficients of NCDs and vacant land characteristics in shrinking and growing cities

| Arthritis | High blood pressure |

Cancer | Asthma | Heart disease |

COPD | Diabetes | High Cholesterol |

Kidney diseases |

Mental health |

Physical health |

Stroke | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj R-squared | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.84 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.74 | ||

| Vacant land physical condition | Vacancy rate (%) | LA (growing) | −0.34 *** | −0.39 ** | −0.11 * | −0.12 *** | −0.05 | −0.10 * | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.06 * |

| SL (shrinking) | 1.15 | 3.68 *** | −0.01 | 0.64 *** | 0.29 | 0.07 | 2.12 *** | 0.19 | 0.43 *** | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.79 *** | ||

| Difference (interaction term) | 1.50 * | 4.07 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.76 *** | 0.35 | 0.17 | 2.16 *** | 0.22 | 0.47 *** | 0.14 | 0.62 | 0.852 *** | ||

| Vacant land mean NDVI | LA (growing) | 0.48 *** | 0.24 | 0.32 *** | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.22 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.28 | −0.26 | 0.01 | |

| SL (shrinking) | 1.81 | 0.17 | 0.98 | −0.40 | 0.67 * | 0.52 | −0.12 | 1.63 * | 0.12 | −0.93 | −0.16 | 0.23 | ||

| Difference (interaction term) | 1.33 | −0.06 | 0.66 | −0.38 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 1.63 | 0.13 | −0.65 | 0.10 | 0.21 | ||

| Vacant land mean size | LA (growing) | 0.41 *** | 0.41 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.08 * | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.05 | |

| SL (shrinking) | 0.12 | 0.13 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.35 | −0.03 | ||

| Difference (interaction term) | −0.29 | −0.28 | −0.22 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.33 | 0.22 | −0.08 | ||

| Vacant land mean duration | LA (growing) | −0.37 | 0.06 | −0.47 | 0.21 | −0.13 | 0.14 | 0.31 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 0.03 | |

| SL (shrinking) | −26.48 * | −64.06 *** | 3.88 | −14.10 *** | −12.25 ** | −20.16 *** | −37.76 *** | −6.98 | −8.03 *** | −24.53 *** | −34.09 *** | −13.88 *** | ||

| Difference (interaction term) | −26.11 * | −64.13 *** | 4.35 | −14.31 *** | −12.12 ** | −20.29 *** | −38.07 *** | −6.95 | −8.00 *** | −25.07 *** | −34.49 *** | −13.92 *** | ||

| Vacant land geographic condition | Vacant land mean distance to multiple family | LA (growing) | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.02 |

| SL (shrinking) | −0.45 | −0.35 | −0.15 | 0.01 | −0.21 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.20 | −0.36 * | −0.07 | 0.00 | −0.25 | −0.10 * | ||

| Difference (interaction term) | −0.41 | −0.27 | −0.17 | 0.06 | −0.20 ** | −0.20 *** | −0.17 | −0.35 * | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.21 | −0.08 | ||

| Vacant land mean distance to single family | LA (growing) | −0.20 *** | −0.14 * | −0.11 *** | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.01 | |

| SL (shrinking) | 0.37 | 0.71 * | −0.05 | 0.17 * | 0.25 * | 0.38 *** | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.12 * | 0.44 * | 0.54 * | 0.19 ** | ||

| Difference (interaction term) | 0.57 * | 0.85 * | 0.06 | 0.18 * | 0.28 * | 0.41 * | 0.38 | 0.04 | 0.13 * | 0.40 * | 0.54 * | 0.20 ** | ||

| Vacant land mean distance to Industrial area | LA (growing) | 0.51 ** | −0.03 | 0.47 *** | −0.17 | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.67 | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.79 | −0.85 | −0.09 | |

| SL (shrinking) | −0.21 | −0.28 | −0.05 | 0.00 | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.15 | −0.06 | ||

| Difference (interaction term) | 0.72 ** | −0.25 | −0.52 *** | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.54 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.03 | |||

| Vacant land mean distance to Commercial | LA (growing) | 0.00 | 0.0001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| SL (shrinking) | 0.00 | 0.005 * | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.001 * | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.001 * | ||

| Difference | 0.00 | 0.005 * | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.001 * | ||

| Green space | Park area (%) | LA (growing) | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| SL (shrinking) | −0.54 | −0.26 | −0.14 | −0.01 | −0.17 | −0.27 | −0.07 | −0.35 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.15 | −0.08 | ||

| Difference (interaction term) | −0.49 | −0.23 | −0.11 | −0.01 | −0.17 | −0.26 | −0.10 | −0.36 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.16 | −0.08 | ||

| Control variables | Population density | Population density | −0.06 *** | −0.03 | −0.04 *** | 0.02 *** | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 * | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 *** | 0.06 *** | 0.00 |

| Social Index | 0.36 | 1.29 *** | −0.16 | 0.34 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.38 *** | 1.06 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.98 *** | 1.26 *** | 0.28 *** | ||

| Social vulnerability | Demographic Index | 0.34 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | |

| Housing & transportation index | −0.05 | −0.31 | 0.10 | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.15 | −0.36 | −0.09 | −0.09 | −0.25 | −0.34 | −0.11 |

Note: * 0.01, ** 0.005, *** 0.001

In Model 3, vacancy rate and average vacant land duration emerged as the two variables most strongly associated with NCDs, exhibiting significant differences between shrinking and growing cities. Vacancy rates in St. Louis were positively correlated with high blood pressure, asthma, diabetes, kidney disease, and stroke, while vacancy rates in Los Angeles were negatively correlated with arthritis, hypertension, cancer, asthma, COPD, and stroke. The coefficients of vacancy rate and arthritis, high blood pressure, cancer, asthma, diabetes, kidney disease, and stroke are statistically significant differences between shrinking and growing cities. Surprisingly, average vacant land duration showed an inverse correlation with all NCDs except cancer and high cholesterol in St. Louis, with significantly lower coefficients compared to Los Angeles.

Regarding vacant land vegetation condition, high NDVI values were associated with an increase in heart diseases and high cholesterol in St. Louis, as well as an increase in arthritis and cancer in Los Angeles. However, these associations did not exhibit significant differences between the cities. Analysis of the average vacant land size revealed that larger areas were associated with a higher risk of arthritis, high blood pressure, and cancer in Los Angeles.

The relationships between health outcomes and vacant land geographic condition variables indicated that in Los Angeles, greater distance between vacant land and single-family areas was associated with better health outcomes. Vacant lands closer to industrial areas were positively related to arthritis and cancer in Las Angeles. Vacant lands closer to single-family areas were linked to higher risks of high blood pressure, asthma, heart disease, COPD, kidney disease, mental health, physical health, and stroke; vacant lands closer to commercial areas were positively related to high blood pressure, kidney disease, and stroke in St. Louis. The associations between vacant lands’ geographic location and NCDs were statistically difference between shrinking and growing cities. After controlling for vacant land characteristics, green spaces show negative relationships with NCDs in St. Louis and mixed relationships with NCDs in Los. Angles, but non-statistically significant in either city.

5. Discussion

5.1. Associations between vacant land characteristics and NCDs

One of the primary objectives of this study was to determine what vacant land characteristics are associated with public health outcomes. The results show that vacancy rate, vacant land vegetation coverage, vacant land size, vacant land duration, and vacant land geographic location are all associated with all 12 NCDs. In St. Louis, NCDs, except for cancer, were associated with at least one of the following: vacancy rate, vacant land vegetation coverage, vacant land duration, and vacant land geographic location. In addition to mental and physical health, NCDs were linked to at least one of the following: vacancy rate, vacant land vegetation coverage, vacant land size, and vacant land geographic location in Los Angeles.

This research also sought to determine if associations in the relationship between vacant land characteristics and public health outcomes differed between shrinking and growing cities. Findings indicate that significant differences in relationships between NCDs and vacancy rates, duration of vacant land, and vacant land geographical location differed significantly in shrinking and growing cities. The interaction analysis confirmed that vacant lands in growing cities like Los Angeles can be seen as thriving or functionally open spaces, as vacancy rates are associated with reductions in arthritis, high blood pressure, cancer, asthma, COPD, and stroke. The high vacancy rate in shrinking cities is often seen as a sign of urban decline and shows a positive correlation with health outcomes such as high blood pressure, asthma, diabetes, kidney disease, and stroke.

Interestingly, the shorter the average duration of the vacant land, the greater the risk of NCDs in a shrinking city. It may seem counterintuitive, but when we study the phenomenon further, it becomes more reasonable. As prior research has shown, vacancy may be contagious to adjacent and nearby lots if not treated (Lee & Newman, 2019). Areas with large amounts of long-term vacant land may also have more newly emerged vacant lands, pulling down the average duration of vacant land at the census tract level. Vacant lands in St. Louis also follows this rule, which is census tracts in the northern region of city with lower socioeconomic status have a higher concentration of vacant land and relatively lower vacant duration than other regions. In such cases, census tracts with the lower duration of vacant lands tend to be areas facing persistent environmental degradation and high public health threats. Moreover, different types of cities need to pay different attention to vacant lands in different locations in terms of public health issues. Vacant lands near industrial areas were more associated with public health issues (namely, arthritis and cancer) in Los Angeles, while vacant lands near single-family and commercial areas were linked to higher risks of NCDs in St. Louis (namely, high blood pressure, asthma, heart disease, COPD, kidney disease, mental health, physical health, and stroke).

We also found that associations between NCDs and vacant land vegetation cover and size were not significantly different between shrinking and growing cities. Vacant lands with dense vegetation cover which are near industrial areas were associated with higher risks of arthritis and cancer in the growing city. One possible explanation for this is that densely vegetated vacant lands can limit wind speeds, thus increasing local pollution concentrations. While most land cover on vacant lands were natural spaces, these can still be fraught with uncertainties about being polluted by previous or current industrial activities (Nowak & Ogren, 2021). Vacant lands with dense vegetation cover near single-family residential areas were linked to increased risks of heart disease and high cholesterol in the shrinking city. This may be because view-obstructing trees and wilder-looking urban spaces in residential areas, especially in lower-income areas, are more likely to be linked to higher crime and decreased emotions of safety when no maintenance is evident, thereby reducing physical activity and increasing stress for residents (Donovan & Prestemon, 2012). From these findings, we can assume that vacant land greening or re-greening does not necessarily equal increases in public health when vacant land regeneration strategies fail to consider the location of vacant land. Although NCDs in the growing city were negatively correlated with vacancy rate, they were positively correlated with the size of vacant land. This may indicate that growing cities, with limited amounts of vacant land, are only significantly impacted if the size of vacant land is at a certain threshold. Future research needs to be conducted to determine this threshold. Surprisingly, vacant land occupied by green spaces, often thought to help improve physical activity and mental health, showed no significant effect on NCDs when controlling for vacant land characteristics. This could be because vacant lands in growing cities actually can be viewed as part of green spaces and serve many of the functions of green spaces, while vacant lands in shrinking cities which may be considered green spaces are often similar simply unused spaces and can attract illegal activities.

5.2. Policy implications

5.2.1. Shrinking cities

Based on the discussion of vacant land factors influencing NCDs, helpful insights from this research emerge which can inform land supply, vacant land regeneration, and green space management policies. Chronic vacant lands in single-family residential and commercial areas could be designated as priority regeneration targets for shrinking cities like St. Louis to improve public health. One of the most applicable ways to address these vacant land features associated with negative health outcomes is to temporarily use them as multifunctional spaces to prevent more land from being contagious from long-term vacant land, reduce vacancy rates, and enhance urban vitality and economic development in a low cost manner (Moore-Cherry & Mccarthy, 2016). Vacant land may be repurposed for a variety of activities that are not normally accepted in regular public areas, such as parks, skateboarding, graffiti creation, pop-up shops, or community farms. These activities help reactivate underutilized areas and swiftly change the view of unoccupied property from degraded, neglected, and dilapidated to functional and vital. This approach also grows local businesses to help build long-term economic resilience (Kim, 2016).

Because conventional regulatory and planning systems and laws controlling land tenure can restrict vacant lands from some types of land use or occupancy, temporary uses derived from community engagement may empower previously excluded people and instill in them a feeling of involvement in the development of place (Németh & Langhorst, 2014). At the same time, it is extremely important to make the converted vacant lands have good visibility and do not have too many obstructions to prevent illegal activities and improve people's sense of security. In addition, maintaining converted vacant lands and existing greenspaces, in shrinking cities is crucial for improving public health, even though it can be challenging.

As such, the results offer some suggestions on how to maintain vacant lots using a minimal budget. First, local governments can prioritize maintenance by allocating funding and resources for vacant land upkeep. This will ensure that regular maintenance is carried out, including mowing, tree trimming, and trash removal. Secondly, community involvement is key to maintaining and repurposing these spaces. Local residents and community groups can volunteer their time to help with maintenance, report any maintenance issues, and help with landscaping and cleaning. Lastly, before renovating vacant land, it is necessary to consider future maintenance costs. Sustainable landscaping practices can be used to maintain green spaces in shrinking cities. This includes planting native species that are resilient to the local climate and water conditions, implementing green infrastructure solutions such as rain gardens and bioswales, and using mulch to reduce water usage. By taking these approaches, residents may have less stress and more chances for exercise in a cleaner, more appealing, and safer environment, thus lowering risks of NCDs (Branas et al., 2011).

5.2.2. Growing cities

Vacant lands in growing cities, as revealed by this research, appear to have less detrimental effects on human health compared to vacant lands in shrinking cities. In fact, they can are often viewed as opportunities for productive open spaces that bring aesthetic and recreational values. However, it is crucial to emphasize that our study's findings do not advocate for ignoring landscaping or maintenance or promoting a complete proliferation of vacant lands in growing cities. Taking a holistic approach to vacant land management is essential, considering factors such as public health, urban planning, and community engagement. Striking a balance between preserving these spaces and ensuring proper maintenance and landscaping is key to maximizing their potential benefits. I small amount of vacant land can be an indicator of healthy economic urban growth and provide an adequate land bank to grow as technologies and populations demand. This includes integrating architectural landscaping principles to transform vacant lands into functional, well-designed green spaces that promote public health and well-being.

It is worth noting that not all vacant lands in growing cities have positive impacts on human health. In the context of Los Angeles, for instance, vacant lands with dense vegetation and large sizes located near industrial zones have been associated with an increased risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). To address this issue, these particular vacant lands should receive higher levels of maintenance and pollution treatment to safeguard the well-being of residents. Government officials and city planners in growing cities should prioritize the regeneration of vacant lands that pose threats to public health, implementing rapid intervention strategies. Moreover, utilizing underutilized vacant spaces is a proven way to add more green spaces in growing cities. Within areas characterized by high population density and limited spaces, repurposing underutilized spaces can provide a significant opportunity to add greenery and improve public health. To achieve this, a collaborative effort is required between local government, private organizations, and the community. Local government can provide incentives for private landowners to repurpose their underutilized spaces into green areas. Community groups can work with local government and private organizations to identify potential spaces, gather support, and raise awareness about the benefits of green spaces. By utilizing vacant lands, growing cities can create a more sustainable and livable city, improving the quality of life for their residents.

6. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the associations between vacant land characteristics and NCDs in both shrinking and growing cities. Our findings align with previous studies, demonstrating that high vacancy rates, densely vegetated vacant land, and vacant land near commercial areas are positively correlated with NCDs in shrinking cities. However, some of our findings for growing cities slightly diverge from previous studies, likely due to the limited focus on shrinking cities in the existing literature. The study emphasizes the significance of considering multiple vacant land characteristics, including vacancy rate, vegetation coverage, size, duration, and geographic location, in understanding their impact on public health outcomes, particularly NCDs. These factors play a crucial role in shaping the health outcomes of communities. Additionally, the associations between vacant land characteristics and NCDs differ between shrinking and growing cities, highlighting the need for tailored strategies and interventions based on the specific urban context. Further, this study underscores the importance of a holistic approach to vacant land management, which takes into account public health considerations, urban planning, and community engagement. Balancing the preservation of vacant lands with proper maintenance and landscaping practices is crucial to maximize their potential benefits for public health.

While the study provides valuable insights, there are limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, the PLACES data has relatively large margins of error compared to larger units of analysis, such as county level and state level data (Browning & Rigolon, 2018). More precise data on NCDs need to be collected and used in the future. Second, because of data limitations, this paper only compared a single shrinking city and a growing city to explore the difference in relationships between vacant lands and NCDs. Future studies need to include more cities to increase generalizability of research findings. Third, this study does not fully reveal real cause and effect connections through the conduction of its longitudinal evaluations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Barker J. (2022). Latest population estimates show St. Louis metro area losing ground, the city dropping below 300,000. STLtoday.Com. https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/latest-population-estimates-show-st-louis-metro-area-losing-ground-the-city-dropping-below-300/article_45648ce9–5e61–5f71–94c6–959a6bd664ad.html.

- Branas CC, Cheney RA, MacDonald JM, Tam VW, Jackson TD, Ten Have TR, 2011. A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. Am. J. Epidemiol 174 (11), 1296–1306. 10.1093/aje/kwr273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branas CC, South E, Kondo MC, Hohl BC, Bourgois P, Wiebe DJ, MacDonald JM, 2018. Citywide cluster randomized trial to restore blighted vacant land and its effects on violence, crime, and fear. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 115 (12), 2946–2951. 10.1073/pnas.1718503115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning MHEM, Rigolon Alessandro, 2018. Do income, race and ethnicity, and sprawl influence the greenspace-human health link in city-level analyses? Findings from 496 cities in the United States, 1541–1541 Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15 (7). 10.3390/ijerph15071541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie ER, Inglis G, Taylor A, Bak-Klimek A, Okoye O, 2022. Is population density associated with non-communicable disease in western developed countries? A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (5), 2638. 10.3390/ijerph19052638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2021, October 18). About the PLACES Project. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/places/about/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- CDC/ATSDR, 2014. CDC/ATSDR’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI). https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html.

- City of St. Louis, MO Open Data. (2022). [22]. Stlouis-Mo.Gov. https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/data/datasets/dataset.cfm.

- Cohen DA, Mason K, Bedimo A, Scribner R, Basolo V, Farley TA, 2003. Neighborhood Physical Conditions and Health. Am. J. Public Health 93 (3), 467–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller B. (2022, November 26). Why are some of Southern California’s most expensive properties left completely empty? Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022–11-26/why-are-some-of-southern-californias-finest-properties-left-empty. [Google Scholar]

- County of Los Angeles. (2022). Assessor Parcels Data 2006 thru 2021. https://data.lacounty.gov/datasets/assessor-parcels-data-2006-thru-2021/about. [Google Scholar]

- Devas N, Rakodi C, 1993. Managing Fast Growing. Cities: New Approaches to Urban Planning and Management in the Developing World. Longman Scientific & Technical. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan GH, Prestemon JP, 2012. The effect of trees on crime in Portland, Oregon. Environ. Behavior 44 (1), 3–30, 44(1), Article 1. [Google Scholar]

- Frakt AB, 2018. How the economy affects health. JAMA 319 (12), 1187–1188. 10.1001/jama.2018.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo C. (2018). St. Louis police issue record number of summonses for illegal dumping, but the problem remains. STLPR. https://news.stlpublicradio.org/health-science-environment/2023–03-30/st-louis-police-issue-record-number-of-summonses-for-illegal-dumping-but-problem-remains. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander JB, Németh J, 2011. The bounds of smart decline: A foundational theory for planning shrinking cities. Hous. Policy Debate 21 (3), 349–367. 10.1080/10511482.2011.585164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter RF, Cleland C, Cleary A, Droomers M, Wheeler BW, Sinnett D, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Braubach M, 2019. Environmental, health, wellbeing, social and equity effects of urban green space interventions: a meta-narrative evidence synthesis. Environ. Int 130, 104923 10.1016/j.envint.2019.104923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Turrisi R, 2003. Interaction Effects in Multiple Regression. SAGE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G., 2016. The public value of urban vacant land: social responses and ecological value. Sustain., 8(5), Artic. 5. 10.3390/su8050486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Miller PA, Nowak DJ, 2018. Urban vacant land typology: a tool for managing urban vacant land. Sustain. Cities Soc 36, 144–156. 10.1016/j.scs.2017.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen S, Fracasso A, Dumoulin SO, Almeida J, Harvey BM, 2021. Size constancy affects the perception and parietal neural representation of object size. NeuroImage 232, 117909. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.117909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Newman G, Park Y, 2018. A comparison of vacancy dynamics between growing and shrinking cities using the land transformation model. Sustainability 10 (5). 10.3390/su10051513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RJ, Newman G, 2019. A classification scheme for vacant urban lands: Integrating duration, land characteristics, and survival rates. J. Land Use Sci 14 (4–6), 306–319. 10.1080/1747423X.2019.1706655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis A, Pardela Ł, Iwankowski P, 2019. Impact of vegetation on perceived safety and preference in city parks. Sustain., 11(22), Artic. 22. 10.3390/su11226324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A. (2021, August 20). From 2010—2020 California’s Population Declined For Reasons Other Than You Might Think. Orange County, CA Patch. https://patch.com/california/orange-county/top-10-fastest-growing-cities-california-see-list. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-García M, Salinas-Ortega M, Estrada-Arriaga I, Hernández-Lemus E, García-Herrera R, Vallejo M, 2018. A systematic approach to analyze the social determinants of cardiovascular disease. PLOS ONE 13 (1), e0190960. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashinini DP, Fogarty KJ, Potter RC, Berles JD, 2020. Geographic hot spot analysis of vaccine exemption clustering patterns in Michigan from 2008 to 2017. Vaccine 38 (51), 8116–8120. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore-Cherry N, Mccarthy L, 2016. Debating temporary uses for vacant urban sites: insights for practice from a stakeholder workshop. Plan. Pract. Res 31 (3), 347–357. 10.1080/02697459.2016.1158075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nassauer JI, Raskin J, 2014. Urban vacancy and land use legacies: a frontier for urban ecological research, design, and planning. Landsc. Urban Plan 125, 245–253. 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. (2022). Tooth Loss in Seniors. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/tooth-loss/seniors.

- Németh J, Langhorst J, 2014. Rethinking urban transformation: temporary uses for vacant land. Cities 40, 143–150. 10.1016/j.cities.2013.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman GD, Bowman AO, Lee RJ, Kim B, 2016. A current inventory of vacant urban land in America. J. Urban Des 21 (3), 302–319. 10.1080/13574809.2016.1167589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman G, Park Y, Bowman AOM, Lee RJ, 2018. Vacant urban areas: causes and interconnected factors. Cities 72, 421–429. 10.1016/j.cities.2017.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NOAA. (2023). National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/.

- Nowak DJ, Ogren TL, 2021. Variations in urban forest allergy potential among cities and land uses. Urban For. Urban Green 63, 127224 10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RC, Ismond D, Rodriquez EJ, Kaufman JS, 2019. Social Determinants of Health: Future Directions for Health Disparities Research. Am. J. Public Health 109 (S1), S70–S71. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.304964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potgieter LJ, Gaertner M, O’Farrell PJ, Richardson DM, 2019. Does vegetation structure influence criminal activity? Insights Cape Town, South Afr. http://hdl.handle.net/10019.1/106260. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Rueda D, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Gascon M, Perez-Leon D, Mudu P, 2019. Green spaces and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet Planet. Health 3 (11), e469–e477. 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30215-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson N, Nassauer J, Schulz A, Hurd K, Dorman C, Ligon K, 2017. Landscape care of urban vacant properties and implications for health and safety: lessons from photovoice. Health Place 46, 219–228. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivak CJ, Pearson AL, Hurlburt P, 2021. Effects of vacant lots on human health: a systematic review of the evidence. Landsc. Urban Plan 208, 104020 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.104020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP (2021). Lots of Potential: Planning Urban Community Gardens as Multifunctional Green Infrastructure. Arizona State University. [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Wen M, Shen Y, Feng Q, Xiang J, Zhang W, Zhao G, Wu Z, 2020. Urban vacant land in growing urbanization: An international review. J. Geogr. Sci 30 (4), 669–687. 10.1007/s11442-020-1749-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- South EC, Kondo MC, Cheney RA, Branas CC, 2015. Neighborhood blight, stress, and health: a walking trial of urban greening and ambulatory heart rate. Am. J. Public Health 105 (5), 909–913. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 89 (2023) 128127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Zhang Q, Pi J, Wan C, Weng M, 2016. Public health in linkage to land use: theoretical framework, empirical evidence, and critical implications for reconnecting health promotion to land use policy. Land Use Policy 57, 605–618. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taggert E, Figgatt M, Robinson L, Washington R, Kotkin N, Johnson C, 2019. Geographic analysis of blood lead levels and neighborhood-level risk factors among children born in 2008-2010. J. Environ. Health 82 (3), 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Immergluck D, 2018. The geography of vacant housing and neighborhood health disparities after the U.S. foreclosure crisis. Cityscape 20 (2), 145–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia. (2023a). Los Angeles. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Los_Angeles&oldid=1164591898. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia. (2023b). St. Louis. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=St._Louis&oldid=1163277780. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu R, Newman G, 2021. The projected impacts of smart decline on urban runoff contamination levels. Comput. Urban Sci 1 (1), 2 10.1007/s43762-021-00002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.