Introduction

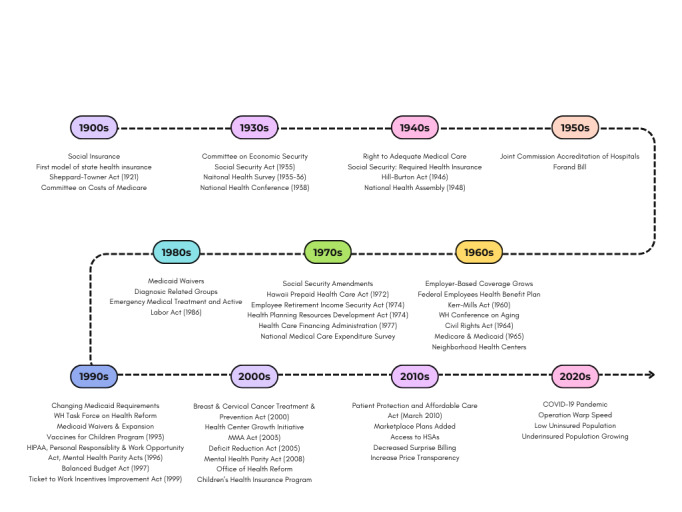

Trying to summarize the history of health policy in the United States is a massive undertaking. What should be included? What should be ignored? How should events be separated? Fortunately, the Kaiser Family Foundation has already done an excellent job of breaking down one thousand years of US health care (see figure 1).1

Figure 1.

Timeline of Major U.S. Health Policy Accomplishments

1900-1929

Health Policy and Reform in the United States began in 1912, when Teddy Roosevelt and the Progressive Party endorsed social insurance as part of their platform. This included health insurance. Not to be outdone, in that same year, the National Convention of Insurance Commissioners developed its first model of state law to regulate health insurance. A few years later, in 1915, the American Association for Labor Legislation drafted a bill to require health insurance. The United States entered World War I soon after, and the bill was not enacted.

In 1921, the Sheppard-Towner Act was passed, providing matching funds to states for prenatal and child health centers.2 This Act would expire in 1929 without being reauthorized. In 1927, the Committee on the Costs of Medical Care was formed to study the economics of medical care. The group included physicians, public health specialists, and others. The recommendation report was published in 1932, and the majority endorsed the ideas of medical group practice and voluntary health insurance.3 By 1929, Baylor Hospital had introduced a pre-paid hospital insurance plan – considered the forerunner of future Blue Cross Plans.

1930-1939

In 1930, the United States was in the midst of the Great Depression (1929-1939), and social policies to secure employment, retirement, and medical care were needed. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed the Committee on Economic Security to address these issues, but a national health reform did not advance. The Social Security Act was passed in 1935, which included grants for Maternal and Child Health, which restored many of the programs established under the Sheppard-Towner Act.4 It also expanded the role of the Children’s Bureau to include child welfare services.

In 1935-1936, the National Health Survey was conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service to assess the Nation’s health, including the underlying social and economic factors that affect health. This survey would go on to become the National Health Interview Survey.

In 1938, the National Health Conference was convened in Washington, D.C. Recommendations from that conference were incorporated into the National Health Bill, which died in committee in 1939. In that same year, the first Blue Shield plans were organized to cover the costs of physician care.

1940-1949

In 1943, legislation was introduced to operate health insurance as a part of social security. The Wagner-Murray-Dingell bill included provisions for universal comprehensive health insurance and changes to social security to move it toward a life-long social insurance. It did not pass. In 1944, President Roosevelt included the right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health in his Economic Bill of Rights State of the Union Address. Also in 1944, the Social Security Board called for required national health insurance as a part of the social security system.

President Harry S. Truman revived the idea of a national health program just after the end of World War II. The Wagner-Murray-Dingell bill was reintroduced to Congress, along with the new Taft-Smith-Ball bill authorizing grants to states for medical care of the poor. Neither bill is passed, and both would be reintroduced in 1947. In 1946, the Hill-Burton Act was passed. This bill funded the construction of hospitals, and prohibited discrimination of medical services on the basis of race, religion, or national origin. It required hospitals to provide a “reasonable volume” of charitable care, and allowed for “separate but equal” facilities.5

In 1948, the National Health Assembly was convened by the Federal Security Agency. The final report called for voluntary health insurance, but also stated the need for universal coverage. That same year, the American Medical Association would launch a national campaign against national health insurance.

1950-1959

In 1951, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Hospitals (JCAH) formed to improve the quality of hospital care. In 1952, the Federal Security Agency proposed the enactment of health insurance for those receiving Social Security benefits. In 1956, a military program was enacted that provided government health insurance for dependents of those serving in the Armed Forces. The Forand Bill was introduced in the house in 1956 to provide health insurance for social security beneficiaries. It was reintroduced in 1959. In 1957, the AMA continued to oppose national health insurance, and the National Health Interview Survey was first conducted (it has been continuously conducted ever since).

1960-1969

As employer-based health coverage grew (and were found to be excluded from an employee’s taxable income), private plans began to set premiums based on their experiences with various health costs. Those individuals who were retired or who were living with a disability found it harder to get affordable coverage.

In 1960, the Federal Employees Health Benefit Plan was begun to provide health insurance to federal workers. The Kerr-Mills Act was passed, which used federal funds to support state programs providing medical care to the poor and elderly (a precursor to Medicaid).6 In 1961, the White House Conference on Aging was held, in which the task force recommended health insurance for the elderly under Social Security. The King-Anderson bill, introduced to create a government health insurance program for the aged, drew support from organized labor and intense opposition from the AMA and commercial health insurance carriers. President Kennedy addressed the nation in 1962 on the topic of Medicare, and President Johnson would continue to advocate for Medicare when he succeeded President Kennedy.

In 1965, a year after the passing of the Civil Rights Act, the Medicare and Medicaid programs were incorporated into the Social Security Act and signed into law by President Johnson.7 The bill had massive public approval, the support of the hospital and insurance industries, and no government cost controls or physician fee schedules within it.

Also in 1965, the Office on Economic Opportunity established Neighborhood Health Centers (precursors to Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)) to provide health and social services to poor and medically underserved communities.

1970-1979

By the early 1970s, inflation and health care costs were both growing. President Nixon put forth the Comprehensive Health Insurance Plan (CHIP), and other congressmen put forth others, splitting support for any one reform.

In 1972, the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program began providing cash assistance to the elderly and disabled. Social Security amendments allowed people under the age of 65 with long-term disabilities and/or end stage renal disease to qualify for Medicare coverage.1 In 1974, The Hawaii Prepaid Health Care Act required employers to provide insurance for any employee working more than 20 hours per week, while the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) exempted self-insured employers from state health insurance regulations. The enactment of the Health Planning Resources Development Act in that same year required states to develop health planning programs to prevent the duplication of services – this resulted in the widespread use of Certificate of Need programs.

In 1977, the Health Care Financing Administration was established within the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (renamed the Department of Health and Human Services in 1980). The National Medical Care Expenditure Survey (NMCES) of that year provided detailed data on how much individuals were spending on health care.

1980-1989

In 1981, a federal budget reconciliation required states to make additional Medicaid payments to hospitals serving a disproportionate share of Medicaid and low-income patients. It also repealed the requirement that Medicaid programs pay hospital rates equal to those paid by Medicare, and required states to pay nursing homes at “reasonable and adequate” rates. Two types of Meidcaid wavers were also established, allowing states to mandate managed care enrollment of certain groups to cover home and community based long-term care. In 1982, states allowed a Medicaid expansion to children who require institutional care but could be cared for at home.1

In 1983, Medicare introduced Diagnostic Related Groups, as a potential payment system for hospital payment. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) was passed in 1986, requiring any hospital participating in Medicare to screen and stabilize all individuals presenting to emergency departments, regardless of their ability to pay. Also in 1986, the federal budget reconciliation gave the option for Medicaid to cover infants, young children, and pregnant women up to 100% of the poverty level regardless of receipt of public assistance.

1987: 31 million (13%) of the population are uninsured

1990-1999

The 1990s were a decade of change for health policy in the United States. In 1990, OBRA 90 required Medicaid coverage of children aged 6-18 who were living under the poverty level.

President Bill Clinton, upon assuming office in 1993, convened a White House Task Force on Health Reform, appointing First Lady Hillary Clinton as the chair. The Health Security Act was introduced to both houses of Congress in November, but gained little support, and saw push back from the Health Insurance Association of America. Other national health reform proposals were introduced to the legislature (McDermott/Wellstone single payer, Cooper’s proposal for managed competition), The Administration began approving Medicaid waivers, allowing statewide expansion, and many states moved toward managed care for service delivery. They also used the cost savings to expand coverage for those previously uninsured. The Vaccines for Children Program was established to provide federally purchased vaccines to states, allowing those parents who were previously unable to afford vaccines due to financial constraints to obtain them for their children.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was passed in 1996, restricting the use of pre-existing conditions in health insurance coverage determinations, setting standards for the privacy of medical records, and favorably taxed long-term care insurance.8 In that same year, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act removed the link between Medicaid and cash assistance eligibility, and allowed states to cover parents and children at higher rates. It also banned Medicaid coverage of legal immigrants in their first five years of living in the country, with an exemption for emergency care. The Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 prohibited group health plans from having lower yearly or lifetime limits for mental health benefits than medical or surgical benefits.9

1997: Approximately 42.4 million (15.7%) are uninsured

In 1997, the Balanced Budget Act was passed, and included

Changes in provider payments to slow Medicare spending and to establish the Medicare + Choice (renamed Medicare Advantage in 2003);

The enactment of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (S-CHIP) to provide block grants to states allowing for health insurance coverage of children who are low-income but whose household is not eligible for Medicaid;

Supplying health insurance for employed individuals with a disability and an income of up to 250% of poverty;

Permission for mandatory Medicaid enrollment in managed care.

In 1999, the Ticket to Work Incentives Improvement Act extended states’ ability to cover working disabled to individuals with incomes above 25% of poverty and gave states the ability impose income-related premiums.

2000-2009

In 2000, the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment and Prevention Act allowed states to provide Medicaid coverage to uninsured women for treatment of breast or cervical cancer, provided they are diagnosed through a CDC screening program, regardless of income. In 2002, President Bush expanded the number of community health centers serving underserved populations with the Health Center Growth Initiative. The next year, the Medicare Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (MMA) was passed, and created a (voluntary) subsidized prescription drug benefit under Medicare. Medicare legislation also created Health Savings Accounts, allowing users to set aside pre-tax dollars to for current and future medical expenses.

In 2005, the Deficit Reduction Act made changes to Medicaid-related premiums, cost sharing, benefits, and asset transfers. Medicare Part D (drug benefits) went into effect in January of 2006, followed by the State of Massachusetts implementing legislation to provide health care coverage for nearly all state residents. One month later, Vermont also passed health care reform aiming for near-universal coverage. The City of San Francisco provided universal access to health services within the city for its residents in that same year.

2007: Approximately 45.6 million (15.3%) are uninsured10

In 2007, Senators Wyden and Bennet introduced the Healthy Americans Act, which would require individuals to obtain private health insurance through a state pool, thus eliminating employer-sponsored insurance programs. The legislation gained bipartisan support, but did not pass. President Bush announced a similar health reform plan replacing employer-sponsored insurance with a standard health care deduction. Congress would not upon it.

Congress passed two versions of a bill to reauthorize S-CHIP with bipartisan support, but President Bush vetoes both bills, and Congress can not override the veto. A temporary extension of the program is passed in December. California fails to pass a health reform plan with an individual mandate and shared financing responsibility.

In 2008, the Mental Health Parity Act was amended to include substance use disorders. Insurance companies must now treat SUD on an equal basis with physical conditions when health policies cover both.9 That same year, the presidential campaign began with a focus on national health reform. Later, this would be overshadowed by a housing crisis and an economic downturn. Both major party candidates announced comprehensive health reform proposals. Senator Baucus (Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee) released a White Paper outlining a national plan based on the Massachusetts model.

In 2009, President Obama established the Office of Health Reform to coordinate administrative efforts on a national health reform. The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) is reauthorized, and provides states with additional funding, tools, and fiscal incentives to heap reach an estimated 4.1 million children who would be otherwise uninsured by Medicaid and CHIP. President Obama’s fiscal year budget for 2010 includes out principles for health reform and proposes $634 billion to be placed in a health reform reserve fund.

2010-2019

On February 22, 2010, the White House released President Obama’s proposal for health care reform. This reform bill includes elements of House and Senate bills passed in the last months of 2009. On March 21, the House of Representatives passes the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, sending it to President Obama for his signature. The Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 was also passed, reflecting amendments and including a reform of the national student loan system.

On March 23, 2010, President Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act into law.11 This historic reform required that all individuals have health insurance by 2014. The poorest individuals will be covered under a Medicaid expansion, and people with incomes in the low to mid-range who do not have access to health insurance through their jobs will be able to purchase with the help of federal subsidies through insurance exchanges. Large businesses who do not provide their employees with health insurance or subsidies will face penalties, and no insurance plan will be allowed to deny coverage for any reason, nor will they be able to charge more due to health status or gender. Young adults will be able to stay on their parents’ health plans until age 26.

In 2016, President Trump eliminated the individual mandate section of the Affordable Care Act, removing monetary penalties for not having health insurance. During his presidency, President Trump added pooled health plans, short-term/limited-duration plans, and new Medicare Advantage plans to the marketplace; lowered Medicare Advantage premiums; and improved access to health savings accounts (HSAs).12 He also took action to end surprise medical billing and increase price transparency.

2020-Now

The COVID-19 pandemic required legislators and policy makers to take a hard look at health care access and utilization. Access to telemedicine and telehealth, which had significant effects on rural and underserved communities was expanded.12 In order to speed up development of COVID-19 vaccines, a partnership between the national Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Defense was formed: Operation Warp Speed (OWS).13 OWS played a key part in selecting vaccine candidates for further study, studying the safety and efficacy of overlapping clinical trial phases to accelerate development, and mitigate vaccine manufacturing challenges like cost, manufacturing, and distribution.13,14

The Biden Administration took action to lower the cost of healthcare, and increase enrollment using the healthcare marketplace.15

August 2023: Approximately 7.7% of the US population is uninsured.16

In the most recent ACA Open Enrollment period, an estimated 16 million people enrolled in health insurance coverage through HealthCare.gov or state websites. Approximately 6.3 million people have gained coverage since 2020. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) enhanced the Affordable Care Act subsidies, and the Inflation Reduction Act extended them, allowing for increased enrollment, a continuous enrollment condition in Medicaid, state Medicaid expansions, and increased outreach by the Biden-Harris administration. Uninsured rates have declined among adults 18-64 (from 14.5% in late 2020 to 11.0% in early 2023) and children aged 0-17 (from 6.4% in 2020 to 4.2% in early 2023), but were largest for individuals with incomes below 100% of the Federal Poverty Level and between 200-400% of the FPL.

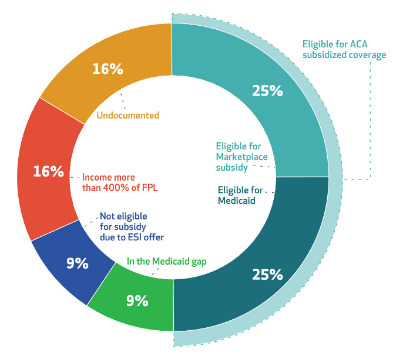

Uninsured

Despite these gains, millions of Americans remain uninsured (see figure 2). Some are eligible for subsidized coverage via Medicaid or the Marketplaces but have yet to enroll, or have lost coverage. The Marketplaces offer challenges (i.e. a perceived lack of affordable options).17 Despite subsidies, affordability remains a barrier for some, especially those at the higher end of income ranges eligible for subsidies. Others are not eligible for subsidies at all, due to having an affordable offer of employer insurance, or being part of the “family glitch:” if an employer-sponsored plan satisfied the affordability threshold for that year, the entire family becomes ineligible for subsidies, even if a family plan through the employer would cost more than the affordability threshold.

Figure 2.

The US Uninsured Population, by Subgroup, 201817

High premiums and premium increases for those paying full price for Marketplace plans, plans exiting the Marketplace, and eligibility confusion.17 Mistrust in the system, navigator and assistance programs also help to lower enrollment rates.

Low enrollment and high dropout rates in Medicaid were present before the ACA, and state approaches to Medicaid (high cost sharing, HSAs, and work requirements) have all been linked to confusion and loss of coverage. Additionally, the “Medicaid Gap” affects people living in states that did not expand Medicaid and have incomes too low to qualify for Marketplace subsidies. They are stuck, with incomes above Medicaid eligibility thresholds, and (potentially) a high burden of chronic conditions.

There are also uninsured immigrants, who are not eligible for any subsidized coverage due to their undocumented status.

Under Insured

Even among those with insurance, barriers to care remain. High deductibles and cost sharing plans have lead patients to cut back on necessary and unnecessary care, especially among low-income adults with chronic conditions.18 Decreasing subsidies, changes in the executive oversight of the ACA, shorter enrollment periods, less advertising outreach, lower-cost and less comprehensive plans are likely to have had an effect on the number of uninsured.17

Conclusion

Whatever the reason, health policy reform has been rife with political and medical backing and arguments since the country started considering a national health insurance program, with no likely end in sight. Health policy is necessary, to codify, equalize, and ensure that everyone has an equal right to good health and wellbeing, regardless of their employment or health state, and each administration pursues their own view of how best to accomplish these efforts.

References

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation. (2011). Timeline: History of health reform in the US. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/5-02-13-history-of-health-reform.pdf

- 2.United States Government. (1921). H.R. 12634, A bill to encourage instruction in the hygiene of maternity and infancy, July 1, 1918. Visitthecapitol.gov. https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/artifact/hr-12634-bill-encourage-instruction-hygiene-maternity-and-infancy-july-1-1918

- 3.Ross, J. S. (2002). The committee on the costs of medical care and the history of health insurance in the United States. The Einstein Quarterly Journal of Biology and Medicine, 19, 129–134. Retrieved from https://einsteinmed.edu/uploadedFiles/EJBM/19Ross129.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Social Security Administration. (n.d.). Historical background and development of social security. https://www.ssa.gov/history/briefhistory3.html

- 5.Harvard University. (2020). Hill-Burton Act. https://perspectivesofchange.hms.harvard.edu/node/23

- 6.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. (n.d.). Putting the program in context. https://www.macpac.gov/putting-the-program-in-context/

- 7.National Archives . (2022). Medicare and Medicaid Act. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/medicare-and-medicaid-act

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Summary of the HIPAA privacy rule. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/index.html

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (n.d.). The mental health parity and addiction equity act. https://www.cms.gov/marketplace/private-health-insurance/mental-health-parity-addiction-equity

- 10.Garfield, R., Orgera, K., & Damico, A. (2019). The uninsured and the ACA: A primer – Key facts about health insurance and the uninsured admidst changes to the Affordable Care Act. KFF. https://www.kff.org/report-section/the-uninsured-and-the-aca-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-amidst-changes-to-the-affordable-care-act-how-many-people-are-uninsured/

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). About the affordable care act. https://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-aca/index.html

- 12.Trump Whitehouse Archives. (n.d.). Healthcare. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/issues/healthcare/

- 13.US Government Accountability Office. (2021, Feb). Operation warp speed. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-319

- 14.National Indian Health Board. (2020). Explaining operation warp speed. https://www.nihb.org/covid-19/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Fact-sheet-operation-warp-speed.pdf

- 15.The White House. (2023). The Biden-Harris Record. https://www.whitehouse.gov/therecord/

- 16.US Department of Health and Human Services. (2023, Aug 3). National uninsured rate reaches and all-time low in early 2023. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/national-uninsured-rate-reaches-all-time-low-early-2023

- 17.Sommers, B. D. (2020, March). Health insurance coverage: What comes after the ACA? Health Affairs (Project Hope), 39(3), 502–508. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brot-Goldberg, Z. C., Chandra, A., Handel, B. R., & Kolstad, J. T. (2017). What does a deductible do? The impact of cost-sharing on health care prices, quantities, and spending dynamics. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(3), 1261–1318. 10.1093/qje/qjx013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]