Abstract

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157:H7 is an attaching and effacing pathogen that causes hemorrhagic colitis and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Although this organism causes adhesion pedestals, the cellular signals responsible for the formation of these lesions have not been clearly defined. We have shown previously that STEC O157:H7 does not induce detectable tyrosine phosphorylation of host cell proteins upon binding to eukaryotic cells and is not internalized into nonphagocytic epithelial cells. In the present study, tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected under adherent STEC O157:H7 when coincubated with the non-intimately adhering, intimin-deficient, enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) strain CVD206. The ability to be internalized into epithelial cells was also conferred on STEC O157:H7 when coincubated with CVD206 ([158 ± 21] % of control). Neither the ability to rearrange phosphotyrosine proteins nor that to be internalized into epithelial cells was evident following coincubation with another STEC O157:H7 strain or with the nonsignaling espB mutant of EPEC. E. coli JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C), which overproduces surface-localized O157 intimin, also rearranged tyrosine-phosphorylated and cytoskeletal proteins when coincubated with CVD206. In contrast, JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) demonstrated rearrangement of cytoskeletal proteins, but not tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins, when coincubated with intimin-deficient STEC (strains CL8KO1 and CL15). These findings indicate that STEC O157:H7 forms adhesion pedestals by mechanisms that are distinct from those in attaching and effacing EPEC. Taken together, these findings point to diverging signal transduction responses to infection with attaching and effacing bacterial enteropathogens.

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157:H7 causes watery diarrhea and hemorrhagic colitis and leads to systemic complications including hemolytic-uremic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in humans (28, 35). STEC of serogroups O157 and O26 is often referred to as enterohemorrhagic E. coli, with STEC of the serotype O157:H7 being most commonly identified in association with human disease (28).

Most STEC strains belong to a family of gastrointestinal bacteria referred to as attaching and effacing (AE) pathogens (28, 35). Phenotypically, an AE lesion is characterized by localized destruction of apical microvilli followed by intimate adhesion of bacteria to the cell plasma membrane (23). At sites of bacterial attachment underneath the host plasma membrane, there is a rearrangement of cytoskeletal proteins including F-actin and α-actinin (16).

The formation of AE lesions by STEC is dependent on the presence of a chromosomal gene, called E. coli attaching and effacing (or eae, formerly eaeA) gene, in the infecting bacterium (3, 38). The eae gene of STEC O157:H7 encodes a 97-kDa outer membrane protein, intimin (24). In vivo studies with a newborn piglet model of infection have shown that STEC strains carrying mutations of eae are unable to attach intimately to host epithelial cells and do not induce F-actin rearrangement (8).

A 35-kb pathogenicity island, termed locus for enterocyte effacement, comprising virulence genes mediating both signal transduction responses and the formation of AE lesions, has been identified in both STEC and the related toxin-negative enteropathogen, enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) (25). This virulence cassette encodes proteins (EspA and EspB) (17, 20) mediating signaling responses in EPEC (13, 21) and the proteins responsible for their secretion via the type III secretion pathway (17). Proteins homologous to EspA and EspB of EPEC have been identified in culture supernatants of some STEC strains (12, 18). However, AE STEC strains of multiple serotypes, including O157:H7, isolated from calves with diarrhea do not consistently test positive for the presence of the espB gene (37).

Although STEC and EPEC share key virulence determinants, there also exist differences between the two groups of enteric pathogens. For example, whereas EPEC strains are considered to be invasive organisms (2, 6), STEC O157:H7 strains are not internalized into nonphagocytic cells (6, 26, 34). We have also reported previously that STEC O157:H7 does not induce a detectable rearrangement of eukaryotic tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins (15). In the present study, we show that the ability of STEC O157:H7 to rearrange phosphotyrosine proteins in infected eukaryotic cells can be induced when it is coincubated with a non-intimately adhering EPEC mutant, strain CVD206. The internalization of STEC O157:H7 by host epithelial cells was also significantly enhanced in the presence of CVD206. We also provide direct evidence to show that cytoskeletal rearrangement in cells infected with STEC O157:H7 occurs independently of phosphotyrosine protein response. These findings point to distinct mechanisms of signal transduction induced in response to infection by AE bacterial enteropathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains employed in this study are listed in Table 1. The bacteria were grown in static nonaerated Penassay (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) broth cultures overnight at 37°C. Strains bearing the plasmids pMH34 and pSSS1C were grown in Penassay broth supplemented with carbenicillin (150 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), respectively (4). EPEC strain E2348/69 was a kind donation of E. Boedeker (University of Maryland, Baltimore). EPEC strains CVD206 and UMD864 and enteroaggregative E. coli strain 17-2 were kindly provided by J. B. Kaper (University of Maryland, Baltimore). STEC strains CL8, CL15, and CL56 were donated by M. A. Karmali (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids employed in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Serotype | Characteristic | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| CL8 | O157:H7 | Wild-type STEC | 24 |

| CL8KO1 | O157:H7 | eae insertional-inactivation mutant of strain CL8 | 24 |

| CL15 | O113:H21 | eae-negative wild-type STEC | 11 |

| CL56 | O157:H7 | Wild-type STEC | 19 |

| E2348/69 | O127:H6 | Wild-type EPEC | 22 |

| CVD206 | O127:H6 | eae deletion mutant of strain E2348/69 | 7 |

| UMD864 | O127:H6 | espB deletion mutant of strain E2348/69 | 9 |

| 17-2 | O3:H2 | Wild-type enteroaggregative E. coli | 36 |

| HB101 | O:rough | Control laboratory E. coli | |

| JM101 | O:rough | Control laboratory E. coli | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pGB19 | 6.1-kb XhoI fragment of eae gene from strain CL8 | 3 | |

| pMH34 | 3.5-kb XhoII fragment of pGB19 | This study | |

| pSSS1C | Encoding F1845, a diffuse adherence fimbrial protein | 4 |

A 3.5-kb XhoII fragment of pGB19 (a plasmid containing the eae gene of STEC O157:H7 strain CL8 [3]) was cloned into the BamHI site of pTRC99A, where expression is under the control of the trc promoter (27). This plasmid, designated pMH34, was then transformed into E. coli JM101 by standard techniques (33). A second recombinant strain was constructed by transforming the diffuse adhesin plasmid pSSS1C (4) (kindly provided by J. R. Cantey, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston) into E. coli JM101. Plasmids pMH34 and pSSS1C were also cotransformed into E. coli JM101. All plasmid transformations were carried out by standard techniques (33).

Eukaryotic cell culture.

The human epithelial tissue culture cell line HEp-2 (ATCC CCL23; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) and the human ileocecal adenocarcinoma cell line HCT-8 (ATCC CCL244) were employed in this study. HEp-2 cells were grown in minimum essential medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (Cansera International Inc., Rexdale, Ontario, Canada). HCT-8 cells were cultivated in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C in 5% CO2. Both media also contained 0.5% glutamine, 0.1% sodium bicarbonate, 2% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% amphotericin B (all from Life Technologies).

Immunofluorescence detection of phosphotyrosine and α-actinin proteins.

Tyrosine-phosphorylated and α-actinin proteins were detected in infected HEp-2 cells, as described previously (15, 16). Briefly, a subconfluent monolayer of HEp-2 cells was infected with approximately 5 × 107 bacteria for 3 h at 37°C in antibiotic-free minimum essential medium. In coinfection studies to detect phosphotyrosine and α-actinin proteins, equal amounts of the two strains, as determined by optical density at 600 nm, were added in each experiment. The cells were then washed free of nonadherent bacteria and either fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min at 25°C for the phosphotyrosine assay or fixed in 100% methanol for 10 min for the α-actinin assay. The detection of phosphotyrosine and α-actinin proteins was performed by staining cells with murine monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology Inc., Lake Placid, N.Y.) and anti-α-actinin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) antibodies, respectively, for 1 h at 37°C. Phosphotyrosine protein localization was confirmed by using two additional murine monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibodies, PY-7E1 and PY-1B2 (both from Zymed Laboratories Inc., South San Francisco, Calif.). After washings, the cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-murine antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, Pa.) for 1 h at 37°C.

In double immunolabeling experiments, isotype-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to either FITC or lissamine rhodamine sulfonyl chloride were employed (Jackson). Foci of intense fluorescence, corresponding to the presence of phosphotyrosine and α-actinin proteins in infected HEp-2 cells, were detected underneath adherent bacteria by alternating phase-contrast and epifluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescent actin staining (FAS).

HCT-8 cells were infected with approximately 2 × 107 recombinant E. coli [strain JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C), JM101(pMH34), or JM101(pSSS1C)] bacteria for 2 h at 37°C alone or in combination with either EPEC strain CVD206 or STEC O157:H7 strain CL8KO1. The assay was then performed as described previously (5, 22). Briefly, cells were washed free of nonadherent bacteria, fixed in 3% formalin, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Following washes with phosphate-buffered saline, tissue culture cells were incubated with FITC-phalloidin (Sigma) at a concentration of 5 μg/ml for 30 min to detect F-actin (27). In the case of coinfection with bacterial strains, prior to being stained for F-actin, fixed and washed HCT-8 cells were incubated with rabbit anti-O127 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.) or rabbit anti-O157 (Difco) antisera, followed by staining with goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to rhodamine (Jackson). The cells were then examined by fluorescence microscopy, as described above.

Transmission electron microscopy.

HCT-8 epithelial monolayers were grown in 75-cm3 tissue culture flasks (Becton Dickinson, Plymouth, England) and infected with approximately 5 × 108 CVD206 cells for 2 h at 37°C. Following washes, the cells were infected for 1 h with JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C). After the monolayer was washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were gently scraped with a rubber policeman. Cells were then fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and postfixed in osmium tetroxide. Samples were then dehydrated through a series of graded ethanol washes, embedded in Spur epoxy resin, and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The grids were then examined under a Philips 300 transmission electron microscope (Philips Electronic Instruments, Mahwah, N.J.) for the presence of AE pedestals.

Bacterial adhesion and gentamicin internalization assays.

HEp-2 cells were grown in 12-well tissue culture plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) to confluence and then infected in antibiotic-free medium with approximately 109 bacteria in 0.01 ml of broth for 3 h at 37°C. In coinfection experiments, equal amounts (approximately 109 cells) of the two strains were incubated with HEp-2 cells for 3 h at 37°C. After the HEp-2 cells were washed to remove nonadherent bacteria, cells with adherent bacteria were detached from the culture plates by incubation with 0.25% trypsin (Life Technologies) for 10 min at 37°C. After centrifugation and lysis of HEp-2 cells in distilled water containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin, serial 10-fold dilutions were plated onto rhamnose MacConkey agar plates and incubated for 16 h at 37°C to determine viable bacterial CFU. The rhamnose MacConkey agar allows for the differentiation of colonies formed by STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 (negative after 16 h) from the colonies of all other strains employed in the coinfection experiments (positive after 16 h).

The gentamicin internalization assay was performed exactly like the adhesion assay until after nonadherent bacteria were washed off. Prior to trypsinization, the cells were incubated in the presence of gentamicin (Schering Canada, Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada) at a concentration of 100 μg/ml for 90 min. The assay was then completed as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± standard errors of the means. Statistical significance between two groups of data was tested by using the nonpaired Student t test. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Induction of the rearrangement of phosphotyrosine proteins in STEC-infected HEp-2 cells by EPEC mutant strain CVD206.

The results of bacterial coinfection experiments to detect phosphotyrosine proteins are summarized in Table 2. Infection of HEp-2 cells with either STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 or EPEC strain CVD206 alone did not lead to an organized rearrangement of phosphotyrosine proteins (data not shown). However, when CL56 was used for coinfection with CVD206 there was an accumulation of phosphotyrosine proteins in the eukaryotic cell underneath the adherent bacteria (Fig. 1A and B). Similar accumulation of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins was also detected with a second STEC O157:H7 isolate, strain CL8, when used for coinfection with CVD206 (Table 2). In contrast, when CVD206 was used for coinfection with the eae insertional-inactivation mutant of CL8, strain CL8KO1, rearrangement of phosphotyrosine proteins was not detected (Fig. 1C and D). These findings indicate that, in the coinfection model system employed, the phosphotyrosine proteins detected by fluorescence microscopy are present underneath the adherent wild-type STEC O157:H7 with functional intimin and not under the eae deletion mutant (i.e., strain CVD206).

TABLE 2.

Phosphotyrosine responses following bacterial coinfection of HEp-2 cells for 3 h at 37°Ca

| Outcome strain | Coinfecting strain

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL56 | CL8 | CL8KO1 | CVD206 | UMD864 | HB101 | |

| CL56 | − | ND | − | + | − | − |

| CL8 | ND | ND | − | + | − | − |

| CL8KO1 | − | − | ND | − | ND | ND |

| CVD206 | − | − | − | − | − | ND |

| UMD864 | − | − | ND | + | ND | ND |

Equal amounts of the coinfecting strains were added in each of the experiments as determined by optical density at 600 nm. + and − denote the presence and absence, respectively, of foci of phosphotyrosine fluorescence underneath the outcome strain. ND, not determined.

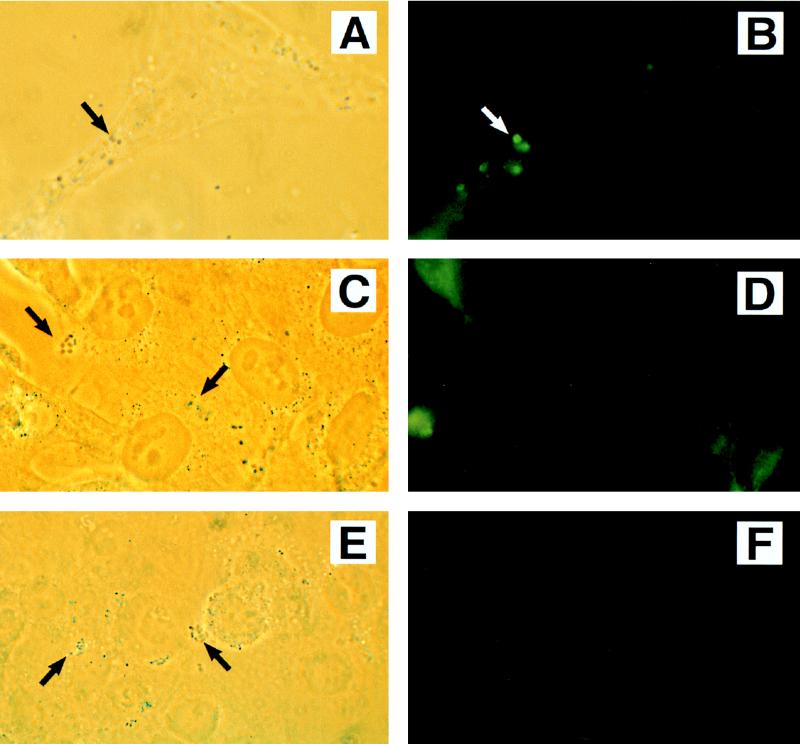

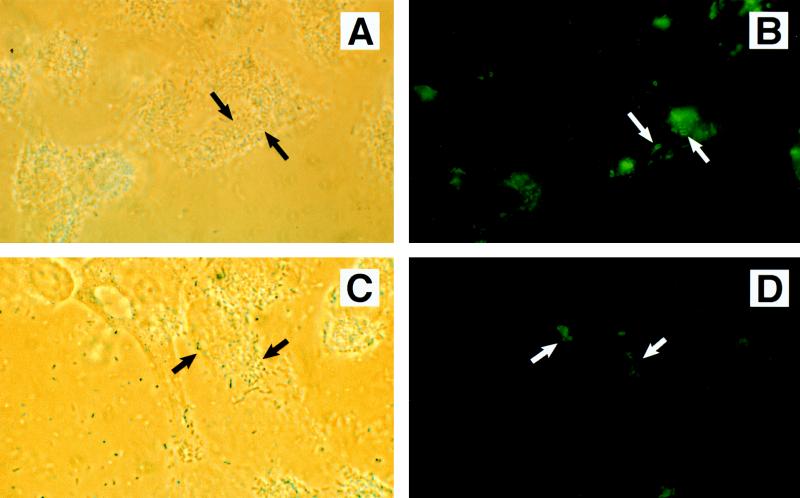

FIG. 1.

Phase-contrast (A, C, and E) and immunofluorescence (B, D, and F) detection of phosphotyrosine proteins in HEp-2 cells following coinfection with STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 plus EPEC strain CVD206 (A and B), STEC O157:H7 strain CL8KO1 plus EPEC strain CVD206 (C and D), and STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 plus EPEC strain UMD864 (E and F). Coinfection by STEC O157:H7 with CVD206 resulted in an accumulation of host phosphotyrosine proteins corresponding to sites of bacterial adhesion (A and B). In contrast, UMD864 did not induce detectable phosphotyrosine signaling in STEC-infected cells (E and F). The absence of phosphotyrosine proteins in a coinfection by intimin-deficient STEC O157:H7 strain CL8KO1 and CVD206 (C and D) confirmed that the phosphotyrosine proteins detected were underneath adherent STEC O157:H7 and not the coinfecting strain CVD206. Approximate original magnification, ×1,000.

The induction of phosphotyrosine protein rearrangement was specific to coinfection with strain CVD206 because incubation of wild-type STEC O157:H7 strains CL8 and CL56 with either another STEC O157:H7 strain or the nonsignaling espB mutant of EPEC, strain UMD864, did not lead to the rearrangement of phosphotyrosine proteins (Fig. 1E and F). Similarly, incubation of STEC O157:H7 strains with a laboratory E. coli strain, HB101, also showed no induction of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins (Table 2). In contrast, when UMD864 was coincubated with strain CVD206, foci of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected (Table 2).

Internalization of STEC is enhanced by coinfection with EPEC strain CVD206.

Figure 2 shows the results of bacterial coinfection experiments for the internalization of STEC O157:H7 strain CL56. When HEp-2 cells were coinfected with STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 and EPEC strain CVD206, there was a significant increase ([158 ± 21] %; P < 0.05) in the internalization of CL56 compared to that when HEp-2 cells were infected alone. Enhancement of invasion was a specific response due to CVD206 since coinfection with either UMD864 or HB101 did not lead to an increase in the internalization of STEC. While CVD206 enhanced the ability of STEC O157:H7 to be internalized, the opposite was not the case. That is, strain CVD206 was internalized to the same levels whether it was used for infection alone or in the presence of STEC O157:H7 strain CL56.

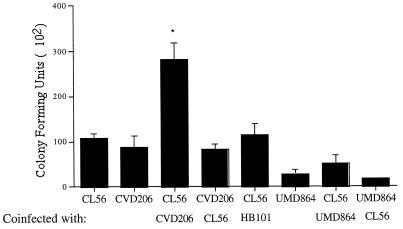

FIG. 2.

Effect of bacterial coinfection on the ability of STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 to be internalized into HEp-2 cells. The colonies of STEC strain CL56 are negative (white) on rhamnose MacConkey agar after 16 h of incubation while the colonies formed by each of the other strains are positive (pink) in the same time period, thereby allowing the differentiation of STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 from each of the other strains. Coincubation of CL56 and CVD206 resulted in an increase in internalization of STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 into HEp-2 cells ([158 ± 21]% of control; t test, P < 0.05 [∗]), but there was no increase in the internalization of EPEC strain CVD206 (P > 0.05). The increased internalization was specifically due to strain CVD206 since neither UMD864 nor HB101 enhanced the invasion phenotype of STEC O157:H7 strain CL56.

To determine whether the observed increase in internalization of STEC O157:H7 upon coincubation with CVD206 was due to an increase in the adherence of the strain to HEp-2 cells, quantitative adhesion assays were performed in conjunction with an invasion assay. Figure 3 shows that with coinfection there was a significant increase in the binding of STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 to HEp-2 cells, whereas there was no effect on the adhesion properties of CVD206. These findings suggest that the increase in internalization of O157:H7 observed upon coinfection with CVD206 was due to an upregulation in the adhesion of STEC O157:H7 to eukaryotic cells.

FIG. 3.

Effects of coinfection by STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 and the eae-deficient EPEC strain CVD206 on adhesion (open bars) and internalization (solid bars) into HEp-2 cells. The strains were distinguished by their differential responses on rhamnose MacConkey agar after 16 h of incubation. An increase in the internalization of CL56 corresponded to an increase in the ability of the organism to adhere to the tissue culture epithelial cells. In contrast, coinfection did not increase the adhesion and internalization properties of CVD206. ∗, P < 0.05.

Intimin expressed by a laboratory E. coli strain, JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C), rearranges both cytoskeletal proteins and phosphotyrosine proteins when the strain is coincubated with EPEC.

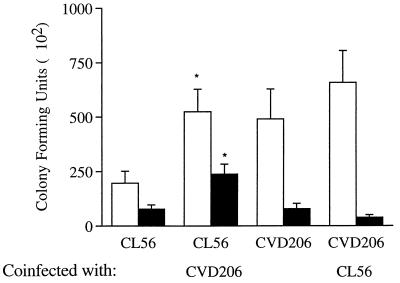

Laboratory E. coli strains overexpressing intiminO157 were then examined for their ability to rearrange cytoskeletal elements when coincubated with CVD206. Rearrangements of F-actin and α-actinin were assessed on HCT-8 and HEp-2 cells, respectively. Coincubation of JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) with CVD206 resulted in a positive FAS response after 2 h of infection of HCT-8 cells, which is observed as organized fluorescence outlining the shape of the bacterium in the form of a “tram line” (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, the FAS pattern due to CVD206 was unorganized and shadowy in appearance (Fig. 4A), signifying its nonintimate attachment to epithelial cells. Furthermore, the bacteria that resulted in an organized tram line of fluorescence (Fig. 4A) were not detected when strain CVD206 was labeled with anti-O127 immune serum followed by staining with a rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (Fig. 4C). These findings demonstrate that the FAS lesions were due to JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) and not to CVD206. Neither JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) nor JM101(pMH34) incubated alone on HCT-8 cells for 3 h resulted in a positive FAS response (data not shown). Coincubation of CVD206 with JM101(pSSS1C) also did not result in detectable FAS lesions (data not shown). These findings indicate that the positive FAS response was specific to the highly adherent recombinant strain expressing intimin encoded by the plasmid pMH34.

FIG. 4.

Immunofluorescence (A) and phase-contrast (B) micrographs of JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) used for coinfection with EPEC strain CVD206 on HCT-8 cells showing a characteristic FAS response (long black arrow in panel A). The FAS response is represented as an organized tram line of fluorescence while the response due to CVD206 (also seen in panel A and labeled with white arrows) is unorganized and shadowy in appearance. The black arrow in panel A points to a representative tram line of FAS response which is not labeled in panel C, in which CVD206 cells are labeled with an anti-O127 serum (white arrows). This result indicated that the FAS lesion is underneath JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) and not CVD206. The EPEC strain CVD206 is also recognized by its capacity to form the microcolonies characteristic of localized adherence (white arrows in panel B). In contrast, E. coli JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) containing the diffuse fimbrial adhesin attaches with the appearance of a single bacterium (black arrow in panel B). Approximate original magnification, ×1,000.

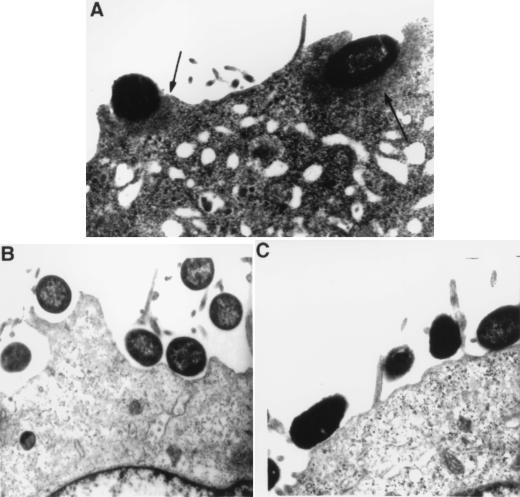

Transmission electron microscopy confirmed the formation of electron-dense adhesion pedestals in tissue culture cells infected for 1 h with JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) following preincubation with CVD206 for 2 h (Fig. 5A). These pedestals were not observed when either of the two bacterial strains was used alone to infect HCT-8 cells (Fig. 5B and C).

FIG. 5.

Transmission electron microscopy showing AE lesions (arrows) formed by JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) following preincubation with CVD206 on HCT-8 cells (A). When either CVD206 (B) or JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) (C) was incubated on the tissue culture cells alone, AE lesions were not formed. Approximate original magnification, ×11,000.

JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) also rearranged α-actinin in HEp-2 cells when coincubated with CVD206 for 3 h (Fig. 6A and B). Neither CVD206 nor JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) alone induced an organized accumulation of α-actinin when incubated on HEp-2 cells (data not shown). In summary, the results demonstrate that EPEC strain CVD206 is able to mediate the formation of AE lesions by JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) overexpressing intiminO157.

FIG. 6.

Phase-contrast (A and C) and immunofluorescence (B and D) detection of α-actinin (A and B) and phosphotyrosine (C and D) proteins in HEp-2 cells coinfected with JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) and EPEC strain CVD206. Distinct foci of fluorescence corresponding to α-actinin and tyrosine-phosphorylated protein rearrangement (arrows) were seen only when the cells were infected with both JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) and CVD206. Approximate original magnification, ×1,000.

Coincubation of JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) with strain CVD206 on HEp-2 cells resulted also in the rearrangement of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins under JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) (Fig. 6C and D). The rearrangement of phosphotyrosine proteins was not evident if the transformed strain was coincubated with the nonsignaling espB mutant of EPEC, strain UMD864 (data not shown). This finding suggests that the induction of tyrosine phosphorylation response was due specifically to the signaling activity of CVD206.

Intimin expressed by JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) rearranges cytoskeletal elements, but not phosphotyrosine proteins, when coincubated with STEC.

Since both EPEC and STEC are able to form AE lesions, it was hypothesized that STEC O157:H7 can also induce the rearrangement of cytoskeletal proteins under JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C). Preincubation of HCT-8 cells for 2 h with the STEC O157:H7 eae insertional-inactivation mutant, strain CL8KO1, resulted in FAS lesions after 1 h of infection with JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) (Table 3). In contrast, diarrheagenic enteroaggregative E. coli strain 17-2 and laboratory E. coli strains (HB101 and JM101) did not result in a positive FAS response when used for coinfection with JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Effect of coincubating EPEC and STEC on the rearrangement of phosphotyrosine and cytoskeletal proteins (F-actin and α-actinin) by the intimin-overproducing E. coli strain JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C)

| Infecting strain(s) | Rearrangement of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phospho- tyrosine | F-actin | α-Actinin | |

| JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) | − | − | − |

| CVD206 | − | − (shadowy)a | − |

| CL8KO1 | − | −b | − |

| CL15 | − | − | − |

| JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) plus CVD206 | + | + | + |

| JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) plus CL8KO1 | − | + | + |

| JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) plus CL15 | − | NDc | + |

Weak unorganized hazy fluorescence in contrast to organized tram line fluorescence.

Reference 24.

ND, not determined.

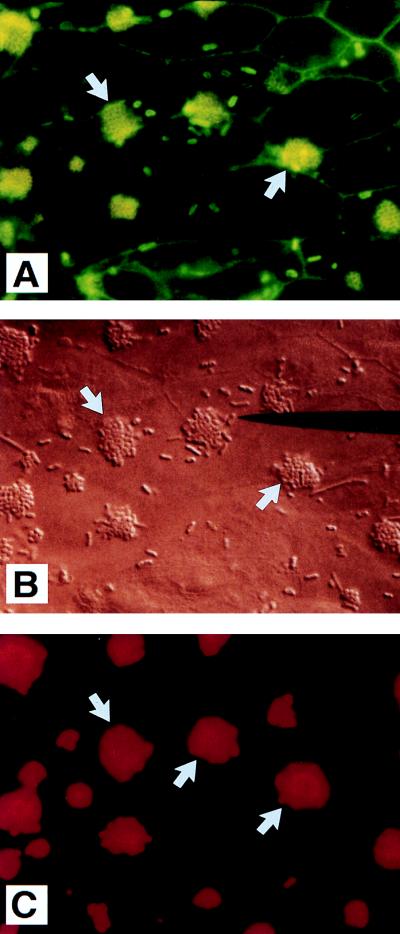

Rearrangement of α-actinin was detected in HEp-2 cells when JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) was coincubated with two different STEC intimin-deficient strains, CL8KO1 (serotype O157:H7) and CL15 (serotype O113:H21) (Fig. 7A and B). Strains CL8KO1 and CL15 incubated alone on HEp-2 cells did not reorganize α-actinin proteins (Table 3).

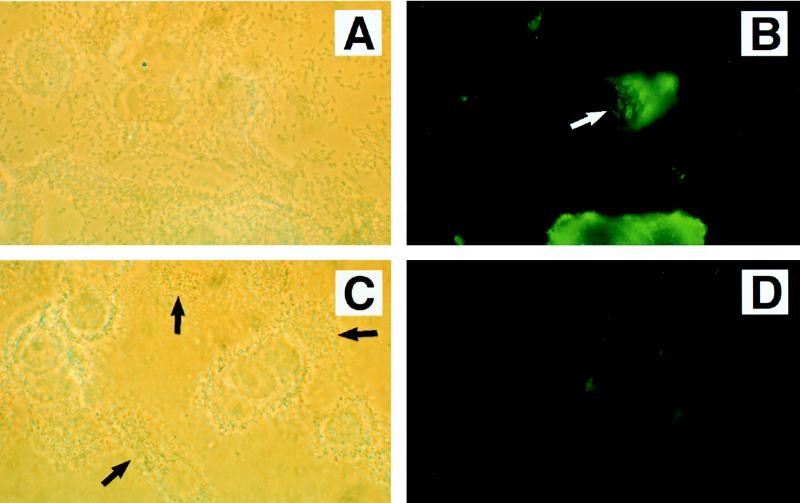

FIG. 7.

Phase-contrast (A and C) and immunofluorescence (B and D) detection of α-actinin (A and B) and phosphotyrosine (C and D) proteins in HEp-2 cells coinfected with JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) and STEC intimin-negative strain CL15 (serotype O113:H21). Numerous foci of fluorescence corresponding to α-actinin rearrangement were seen (arrow in panel B). In contrast, no detectable accumulation of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins was observed. Approximate original magnification, ×1,000.

In contrast to their ability to mediate the reorganization of F-actin and α-actinin, STEC strains CL8KO1 and CL15 failed to induce detectable tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins following coincubation with JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C) (Fig. 7C and D). Therefore, while STEC can mediate the rearrangement of cytoskeletal elements when incubated with a laboratory E. coli strain expressing intimin, in contrast to EPEC, STEC O157:H7 and STEC O113:H21 do not induce the rearrangement of phosphotyrosine proteins.

STEC induces the rearrangement of cytoskeletal elements independently of tyrosine phosphorylation.

Simultaneous detection of α-actinin and phosphotyrosine proteins in HEp-2 cells infected with STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 showed the rearrangement of α-actinin in the absence of phosphotyrosine proteins (data not shown). In contrast, EPEC strain E2348/69 showed rearrangement of both phosphotyrosine proteins and α-actinin at sites of bacterial attachment (data not shown). These results indicate that the rearrangement of cytoskeletal elements, including α-actinin, can occur in STEC O157:H7-infected cells in the absence of detectable tyrosine phosphorylation.

DISCUSSION

STEC strains of multiple serotypes (including O157:H7) induce the activation of intracellular second messenger molecules, including inositol triphosphate and intracellular calcium, in infected eukaryotic cells in tissue culture (15). Many STEC strains are also able to induce AE lesions consisting of cytoskeletal elements, including F-actin and α-actinin, in infected host epithelial cells (10, 26). When examined by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, STEC O157:H7 strains do not induce the tyrosine phosphorylation of host cell proteins (15) that is evident following EPEC infection (30).

In this study, we have shown that, by infecting tissue culture cells with both an EPEC eae-deficient mutant (strain CVD206) and an O157:H7 strain, the rearrangement of phosphotyrosine proteins could then be detected in the AE lesions underneath adherent STEC O157:H7. The accumulation of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins was underneath STEC O157:H7, and not CVD206, because the latter strain lacks the functional outer membrane protein, intimin, required for reorganizing cytoskeletal and phosphotyrosine elements (30). The finding that an eae mutant of STEC (strain CL8KO1) employed in a coinfection experiment with CVD206 did not lead to the organized accumulation of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins also indicates that the proteins detected are underneath adherent STEC O157:H7 and not CVD206. Neither the espB mutant, strain UMD864, nor the laboratory E. coli strain was able to induce tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins under adherent wild-type STEC O157:H7. The tyrosine phosphorylation observed under the adherent STEC did not occur when a STEC O157:H7 counterpart of CVD206, strain CL8KO1, was used in the coinfection experiments.

It has not been possible to induce the phosphotyrosine response or upregulate internalization properties of STEC O157:H7 by using concentrated supernatants prepared from wild-type EPEC. Kenny and Finlay (20) have also reported that soluble EPEC-secreted proteins alone do not induce tyrosine phosphorylation of eukaryotic cells. Filtered bacterial sonicates and outer membrane preparations of EPEC also fail to mediate phosphotyrosine responses in HEp-2 cells infected with STEC. Taken together, these findings indicate that contact of the intact bacterium likely is required for the induction of signal transduction responses. It is also possible that the signaling proteins have a short half-life, thereby requiring the presence of actively secreting bacteria (27). These observations are comparable to those described for Yersinia species in which the action of YopE on host cells is contact dependent (32).

Rosenshine et al. (30) showed that the ability of EPEC strain E2348/69 to induce internalization into nonphagocytic cells is dependent on the prior phosphorylation of host cell proteins at tyrosine residues. Mutants unable to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of host cell proteins do not invade the cytosol of eukaryotic cells (30). STEC O157:H7 strains are normally considered to be noninvasive (6, 26, 34). As a result, we speculated that STEC O157:H7 strains are not internalized because they do not induce tyrosine phosphorylation of eukaryotic proteins. Therefore, the internalization of STEC O157:H7 following coincubation with CVD206 was determined. Coinfection with CVD206 led to an increase in the internalization of STEC O157:H7 into HEp-2 cells. Similar to the phosphotyrosine responses, increases in internalization were specifically related to factors provided by strain CVD206 because coinfection with either the espB mutant or a laboratory E. coli strain did not mediate an increase in the internalization of STEC O157:H7 into tissue culture cells. The upregulation in internalization of STEC O157:H7 was not simply a nonspecific effect of bacterial coinfection since an increase in the internalization of CVD206 did not occur. The upregulation of internalization observed with STEC O157:H7 in this study is comparable to previous findings with EPEC in which the invasion of mutants deficient in a secreted protein, either EspA or EspB, is enhanced upon coinfection with the eae deletion mutant CVD206 (13, 21).

Although there is no detectable difference in the secretion of EspA and EspB proteins by the STEC strains employed in this study, including serotype O113:H21 strain CL15 (14a), it is possible, of course, that the proteins secreted by STEC have different structural or functional properties than EspA and EspB derived from EPEC. Indeed, Ebel et al. (12) reported the presence of a stretch of 18 amino acids in the N terminus of EspB derived from EPEC which is not highly conserved in the EspB of STEC of serogroup O26. Furthermore, this amino acid sequence is similar to that present in internalin A, an outer membrane protein essential for the invasion of Listeria monocytogenes in vitro (14). More recently, Abe et al. (1) reported that EspBs of RDEC-1 and STEC (serogroups O157 and O26) have conserved deletions in the C terminus, which are not found in the EspB of EPEC O127. Furthermore, the ability of RDEC-1 to be internalized into HeLa cells was enhanced when it harbored a plasmid carrying the espB gene derived from EPEC (1). In the present study, we have shown that STEC O157:H7 can also be induced to be internalized into HEp-2 cells when coincubated with an EPEC strain capable of secreting a wild-type EspB protein.

The increase in internalization observed for STEC O157:H7 strain CL56 was the result of a corresponding increase in the adhesion of this strain upon coincubation with CVD206. This contrasts with the findings in previous studies with EPEC mutants in which the lack of internalization could not be accounted for by changes in bacterial adhesion (21).

In this study, we also have shown that a laboratory E. coli strain bearing the cloned STEC O157:H7 intimin gene, JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C), is able to induce AE lesions in HEp-2 cells when they are coinfected with CVD206. Thus, intiminO157 specified by the plasmid pMH34 is fully functional for the formation of AE lesions if accessory signals are provided. This finding indicates that intimin does not require specific intracellular activation, processing, or other bacterial membrane proteins in order to reorganize underlying cytoskeletal elements (27). This conclusion is in agreement with the previous results showing that JM101 containing the eae gene from EPEC is able to cause cytoskeletal rearrangement only if preinduced by CVD206 (31). In addition, the recombinant strain is able to rearrange phosphotyrosine proteins when coincubated with CVD206.

We also show, for the first time, that STEC strains are able to induce rearrangement of cytoskeletal proteins in cells infected with recombinant strain JM101(pMH34/pSSS1C). In contrast to induction of cytoskeletal assembly, however, STEC strains of serotypes O157:H7 and O113:H21 fail to induce detectable rearrangement of phosphotyrosine proteins. Therefore, while the signaling for cytoskeletal elements provided by STEC is functionally homologous to that provided by EPEC, it likely does not occur via a protein tyrosine kinase-mediated pathway.

By employing double immunofluorescence labeling techniques in the present study, we have confirmed and extended earlier findings indicating that rearrangements of cytoskeletal proteins, including F-actin and α-actinin, occur independently of detectable tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in STEC O157:H7-infected eukaryotic cells. These results are in agreement with a recent report by Rabinowitz et al. (29) showing AE lesion formation by an EPEC strain in the absence of detectable tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins. In addition, this strain also failed to secrete into culture supernatants detectable levels of the proteins currently implicated in the generation of signal transduction responses to EPEC infection, including EspA and EspB (29). Taken together, these findings indicate that the rearrangement of cytoskeletal proteins following STEC O157:H7 infection can occur by novel signal transduction mechanisms that are not dependent upon prior phosphorylation of host cell proteins at tyrosine residues. This contrasts with a proposed model for signal transduction by EPEC in which the cytoskeletal rearrangement is dependent on the upstream activation of host protein tyrosine kinases (31). Therefore, these findings suggest that STEC O157:H7 induces cytoskeletal reorganization and the formation of AE lesions by signal transduction mechanisms that are distinct from those that have been described to date with AE EPEC strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A.I. is the recipient of an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. This work was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada and an A. C. Finkelstein award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe A, Kenny B, Stein M, Finlay B B. Characterization of two virulence proteins secreted by rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, EspA and EspB, whose maximal expression is sensitive to host body temperature. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3547–3555. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3547-3555.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade J R C, Da Veiga V F, De Santa Rosa M R, Suassuna I. An endocytic process in HEp-2 cells induced by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Med Microbiol. 1989;28:49–57. doi: 10.1099/00222615-28-1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beebakhee G, Louie M, De Azavedo J, Brunton J. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the eae gene homologue from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;91:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilge S S, Clausen C R, Lau W, Moseley S L. Molecular characterization of a fimbrial adhesin, F1845, mediating diffuse adherence of diarrhea-associated Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4281–4289. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4281-4289.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cockerill F, III, Beebakhee G, Soni R, Sherman P. Polysaccharide side chains are not required for attaching and effacing adhesion of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3196–3200. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3196-3200.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnenberg M S, Donohue-Rolfe A, Keusch G T. Epithelial cell invasion: an overlooked property of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) associated with the EPEC adherence factor. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:452–459. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4310–4317. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4310-4317.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnenberg M S, Tzipori S, McKee M L, O’Brien A D, Alroy J, Kaper J B. The role of the eaeA gene of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in intimate attachment in vitro and in a porcine model. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1418–1424. doi: 10.1172/JCI116718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnenberg M S, Yu J, Kaper J B. A second chromosomal gene necessary for intimate attachment of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4670–4680. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4670-4680.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dytoc M, Soni R, Cockerill III F, de Azavedo J, Louie M, Brunton J, Sherman P. Multiple determinants of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 attachment-effacement. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3382–3391. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3382-3391.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dytoc M T, Ismaili A, Philpott D J, Soni R, Brunton J L, Sherman P M. Distinct binding properties of eaeA-negative verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli of serotype O113:H21. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3494–3505. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3494-3505.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebel F, Deibel C, Kresse A U, Guzman C A, Chakraborty T. Temperature- and medium-dependent secretion of proteins by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4472–4479. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4472-4479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foubister V, Rosenshine I, Donnenberg M S, Finlay B B. The eaeB gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is necessary for signal transduction in epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3038–3040. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.3038-3040.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaillard J L, Berche P, Frehel C, Gouin E, Cossart P. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into cells is mediated by internalin, a repeat protein reminiscent of surface antigens from gram-positive cocci. Cell. 1991;65:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90009-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Ismaili, A., et al. Unpublished data.

- 15.Ismaili A, Philpott D J, Dytoc M T, Sherman P M. Signal transduction responses following adhesion of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3316–3326. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3316-3326.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ismaili A, Philpott D J, Dytoc M, Soni R, Ratnam S, Sherman P M. Alpha-actinin accumulation in epithelial cells infected with attaching and effacing gastrointestinal pathogens. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1393–1396. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarvis K G, Giron J A, Jerse A E, McDaniel T K, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contains a putative type III secretion system necessary for the export of proteins involved in attaching and effacing lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7996–8000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarvis K G, Kaper J B. Secretion of extracellular proteins by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli via a putative type III secretion system. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4826–4829. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4826-4829.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karmali M A, Petric M, Lim C, Fleming P C, Arbus G S, Lior H. The association between idiopathic hemolytic uremic syndrome and infection by Verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:775–782. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenny B, Finlay B B. Protein secretion by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is essential for transducing signals to epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7991–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenny B, Lai L C, Finlay B B, Donnenberg M S. EspA, a protein secreted by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, is required to induce signals in epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knutton S, Baldwin T, Williams P H, McNeish A S. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1290–1298. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1290-1298.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Law D. Adhesion and its role in the virulence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:152–173. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louie M, de Azavedo J C S, Handelsman M Y C, Clark C G, Ally B, Dytoc M, Sherman P, Brunton J. Expression and characterization of the eaeA gene product of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4085–4092. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4085-4092.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKee M L, O’Brien A D. Investigation of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence characteristics and invasion potential reveals a new attachment pattern shared by intestinal E. coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2070–2074. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.2070-2074.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McWhirter E. Characterization of the interaction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 intimin with a human colonic epithelial cell line (HCT-8). M.S. thesis. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philpott D J, Sherman P M. Signal transduction responses in eukaryotic cells following Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infection. Germs Ideas. 1995;1:15–21. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3316-3326.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabinowitz R P, Lai L-C, Jarvis K, McDaniel T K, Kaper J B, Stone K D, Donnenberg M S. Attaching and effacing of host cells by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in the absence of detectable tyrosine kinase mediated signal transduction. Microb Pathog. 1996;21:157–171. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenshine I, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Finlay B B. Signal transduction between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and epithelial cells: EPEC induces tyrosine phosphorylation of host cell proteins to initiate cytoskeletal rearrangement and bacterial uptake. EMBO J. 1992;11:3551–3560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenshine I, Ruschkowski S, Stein M, Reinscheid D J, Mills S D, Finlay B B. A pathogenic bacterium triggers epithelial signals to form a functional bacterial receptor that mediates actin pseudopod formation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2613–2624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosqvist R, Magnusson K E, Wolf-Watz H. Target cell contact triggers expression and polarized transfer of Yersinia YopE cytotoxin into mammalian cells. EMBO J. 1994;13:964–972. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherman P, Soni R, Petric M, Karmali M. Surface properties of the Vero cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1824–1829. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1824-1829.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tesh V L, O’Brien A D. Adherence and colonization mechanisms of enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90043-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vial P A, Robins-Browne R, Lior H, Prado V, Kaper J B, Nataro J P, Maneval D, Elsayed A, Levine M M. Characterization of enteroadherent-aggregative Escherichia coli, a putative agent of diarrheal disease. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:70–79. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wieler L H, Vieler E, Erpenstein C, Schlapp T, Steinruck H, Bauerfeind R, Byomi A, Baljer G. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from bovines: association of adhesion with carriage of eae and other genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2980–2984. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2980-2984.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu J, Kaper J B. Cloning and characterization of the eae gene of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:411–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]