Abstract

Purpose of Review

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide. Heart failure has been defined as a global pandemic leading to millions of deaths. Recent research clearly approved the beneficial effect of Coenzyme Q10 supplementation in treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with heart failure in clinical trials but did not distinguish between the oxidised form CoQ10 and reduced form CoQH2 of Coenzyme Q10. The aim of this study is to determine differences in medical application of CoQ10 and CoQH2 supplementation and evaluate the efficacy of CoQ10 and CoQH2 supplementation to prevent cardiovascular disease in patients with heart failure.

Recent Findings

A PubMed search for the terms “ubiquinone” and “ubiquinol” was conducted, and 28 clinical trials were included. Our findings go along with the biochemical description of CoQ10 and CoQH2, recording cardiovascular benefits for CoQ10 and antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties for CoQH2. Our main outcomes are the following: (I) CoQ10 supplementation reduced cardiovascular death in patients with heart failure. This is not reported for CoQH2. (II) Test concentrations leading to cardiovascular benefits are much lower in CoQ10 studies than in CoQH2 studies. (III) Positive long-term effects reducing cardiovascular mortality are only observed in CoQ10 studies.

Summary

Based on the existing literature, the authors recommend CoQ10 instead of CoQH2 to treat and prevent cardiovascular disease in patients with heart failure.

Keywords: Coenzyme Q10, Heart failure, Ubiquinone, Ubiquinol

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide [1]. Heart failure (HF) has been defined as a global pandemic leading to millions of deaths [2]. HF is described as clinical syndrome with symptoms and/or signs caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality and corroborated by elevated natriuretic peptide levels and/or objective evidence of pulmonary or systemic congestion [3]. During the last decades, Coenzyme Q10 has been established as adjunctive therapy for CVD and HF [4].

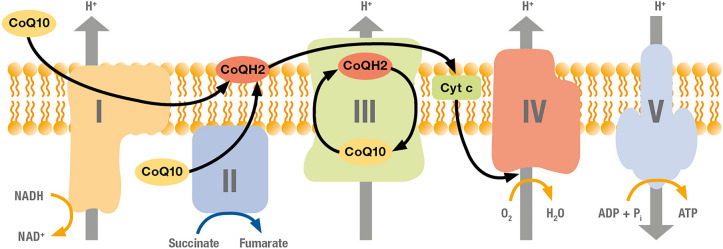

Coenzyme Q10 is a redox molecule occurring in the human body in 2 bioactive states, ubiquinone (CoQ10) as oxidised state and ubiquinol (CoQH2) as reduced state [5]. Both redox forms of Coenzyme Q10 are bioactive and important for human health [6]. CoQ10 is essential for cellular adenosine phosphate (ATP) energy production [7] as it shuttles electrons from complexes I and II to complex III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (Fig. 1). CoQH2 is an important lipid-soluble antioxidant preventing peroxidation of the low-density lipoproteins in the blood circulation [8] with additional anti-inflammatory activity [9].

Fig. 1.

Function of CoQ10 in the mitochondrial respiratory chain. CoQ10 is an essential transfer molecule for complex I and complex II at the beginning of the respiratory chain

A slightly better water solubility and a lack of understanding absorption and transfer of CoQ10 and CoQH2 have led to misleading interpretations pushing CoQH2 as more bioactive form [10•]. Therefore, it is important to notice that (I) CoQH2 is very unstable [11] and under normal conditions oxidised to CoQ10 [12], (II) CoQH2 has to be oxidised to CoQ10 before it can be absorbed in enterocytes [6], (III) the bioavailability of CoQ10 and CoQH2 mainly depends on crystal dispersion status and carrier oil composition [13].

Interestingly, only CoQ10 is synthesised in the human body by way of the mevalonate pathway, an essential metabolic pathway including byproducts like cholesterol and other isoprenoids. And this shared dependence on the mevalonate pathway was the reason for focusing attention to CoQ10 in CVD [14].

Recent reviews clearly approved the beneficial effect of Coenzyme Q10 supplementation in treatment and prevention of CVD in clinical trials but did not distinguish between CoQ10 and CoQH2 supplementation [15]. As comparative clinical trials are missing and misleading marketing claims are revealed [10•], a critical view comparing the effectivity of supplementation with CoQ10 and CoQH2 in CVD therapies is needed.

Objectives

Our goal is to determine differences in medical application of CoQ10 and CoQH2 supplementation and evaluate the efficacy of CoQ10 and CoQH2 supplementation to prevent cardiovascular diseases. The final aim is to identify the most promising supplement to reduce cardiovascular mortality in patients with heart failure. We focused on the medical evidence that can be found in the literature.

Methods

Search Methods

We searched PubMed for the term “ubiquinone” and “ubiquinol” from 5 to 12th July 2023. We applied no language restrictions. We used the filter “randomized controlled trial” and searched for results published between 1993 and 2023.

Selection Criteria

Only randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled, parallel or cross‐over trial has been included. Trials investigated the supplementation of CoQ10 or CoQH2 alone or with one other single supplement. We excluded any trials involving multifactorial lifestyle interventions to avoid confounding. Trials including children or lacking necessary information or comparability have been excluded from the evaluation of ubiquinone and ubiquinol supplementation to prevent cardiovascular diseases. We excluded studies with a daily CoQ10 or CoQH2 intake lower than 50 mg. Follow-up-studies with own objectives are treated as separate studies.

Types of Outcome Measures

To determine differences in medical application of CoQ10 and CoQH2 supplementation, we assigned the studies to the following applications: antioxidative activity, bronchial diseases, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, eye diseases, hepatic diseases, Huntington, infections, infertility, inflammation, mental health, metabolic syndrome, migraine, mitochondrial dysfunction, pain, Parkinson, physical health, polycystic ovary syndrome, pregnancy, presbycusis, statin associated pain, others.

In case of the evaluation of CoQ10 and CoQH2 as prevention of cardiovascular disease, we recorded reduced cardiovascular mortality, clinical status, echocardiography, 6-min walk test, NYHA, E/e´, EF, B-type natriuretic peptides (BNP) and hospitalisation.

We further compared the reduction of cardiovascular mortality in patients with heart failure as main result to identify the most promising supplement.

Data Collection and Analysis

Two authors independently selected trials for inclusion, abstracted data and assessed the risk of bias.

Results

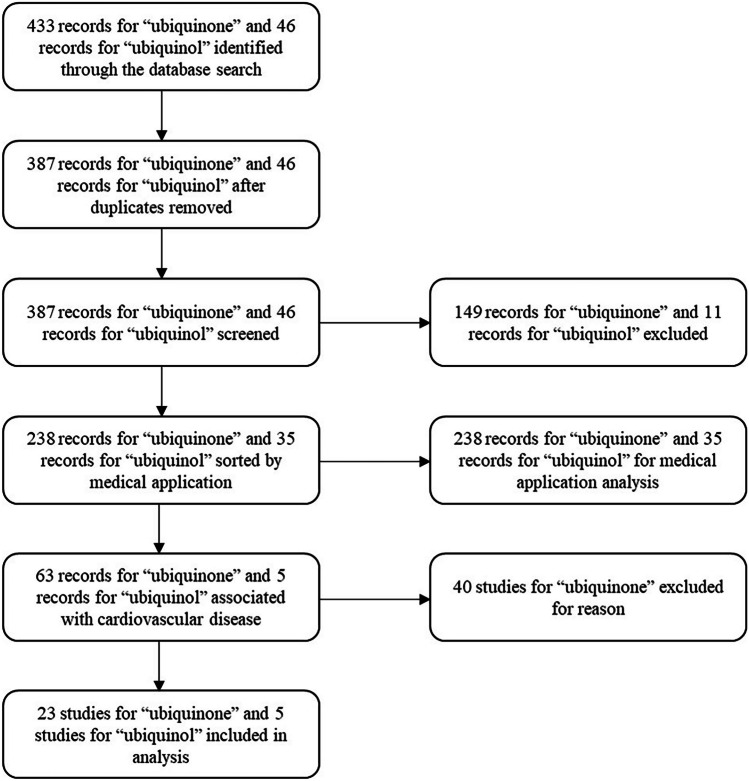

We identified 238 randomised controlled trials for ubiquinone and 35 for ubiquinol, which were sorted by medical application. Twenty-three studies of ubiquinone and 5 of ubiquinol were included to analyse their potential to prevent cardiovascular disease. These 28 studies were compared according to the ability of the given supplements to reduce cardiovascular mortality in patients with heart failure (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Study flow diagram

Different Medical Applications of CoQ10 and CoQH2 Supplementation

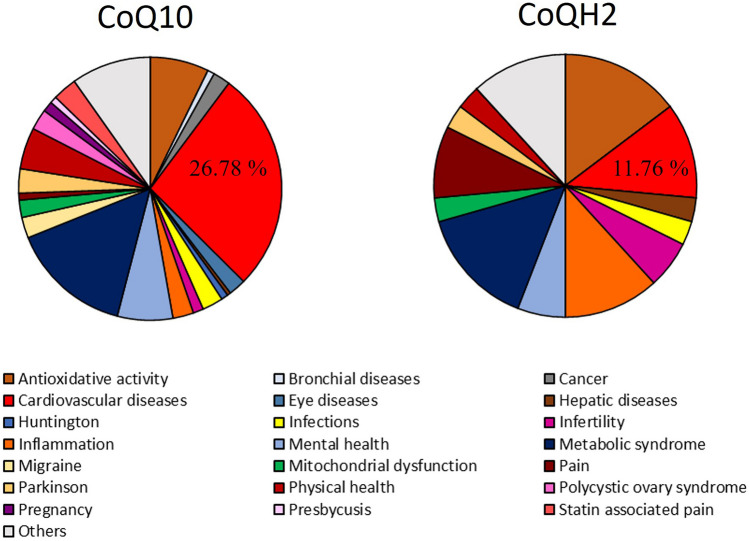

We associated a total of 273 studies with 21 medical applications. Studies with unclear applications or with applications recorded only once are included in the group “Others”. According to the different study numbers of CoQ10 and CoQH2, relative results are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of CoQ10 and CoQH2 by application. Results are demonstrated as %. Cardiovascular diseases are marked in red

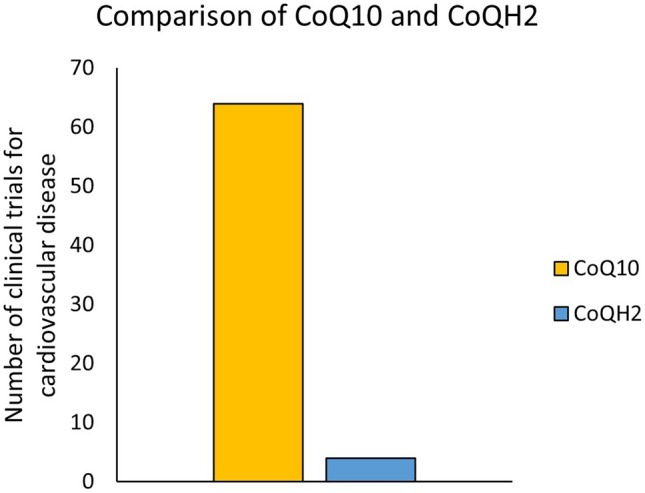

By comparison of applications, CoQ10 can be identified as promising agent to treat cardiovascular diseases while CoQH2 can be preferred for treatment of inflammation and antioxidative activity. These findings go along with the biochemical description of CoQ10 and CoQH2 [7, 8]. The different clinical evidence for the usage of CoQ10 and CoQH2 as supplement for cardiovascular disease is demonstrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of CoQ10 and CoQH2. Given is the number of clinical trials associated with cardiovascular disease for both supplements

At this point, it should be mentioned that the enormous difference in the number of conducted studies (6.8-fold difference) suggests that CoQ10 is better investigated than CoQH2. The number of clinical trials for CoQH2 is limited [10•].

Effects of CoQ10 and CoQH2 on Cardiovascular Diseases

Results of 28 studies (23 original studies and 5 follow-up studies with specific aims) investigating the effects of CoQ10 and CoQH2 on cardiovascular diseases are demonstrated in Table 1. In the original studies, 3523 are included.

Table 1.

Effects of CoQ10 and CoQH2 on cardiovascular diseases. Empty cells are used if information is missing

| Author | Year | Probands included | Duration supplementation/(study) [weeks] | Daily intake (mg/d) | Effect | Reduced cardiovascular mortality (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoQ10 | Judy et al. [16] | 1993 | 20 | 6/(6) | 100 | Improved echocardiogram and improved EF | |

| Morisco et al. [17] | 1993 | 641 | 52/(52) | 160 | Reduced time of hospitalisation | ||

| Chello et al. [18] | 1994 | 40 | 1/(1) | 150 | No reduced cardiovascular mortality | 0 | |

| Morisco et al. [19] | 1994 | 6 | 4/(8) | 200 | Improved echocardiogram Improved EF | ||

| Singh et al. [20] | 1998 | 144 | 4/(4) | 120 | Reduced cardiovascular mortality | 15.90 | |

| Berman et al. [21] | 2004 | 32 | 12/(12) | 60 | Improved clinical status, improved 6-min walk test and improved NYHA class | ||

| Chew et al. [22] | 2008 | 74 | 24/(24) | 160 | No improved E/e´ ratio | ||

| Makhija et al. [23] | 2008 | 30 | 7/(7) | 165 | Reduced time of hospitalisation | ||

| Kuimov et al. [24] | 2013 | 8/(8) | 60 | Improved clinical status | |||

| Mortensen et al. [25••] | 2014 | 420 | 16/(104) | 300 | Improved NYHA class, reduced time of hospitalisation and reduced cardiovascular mortality | 18.00 | |

| Aslanabadi et al. [26] | 2016 | 100 | 0.14/(0.14) | 300 | Reduced cardiovascular mortality | 2.00 | |

| Mortensen et al. [27] | 2019 | 231 | 12/(96) | 300 | Improved NYHA class, improved EF, reduced time of hospitalisation and reduced cardiovascular mortality | 11.00 | |

| Sobirin et al. [28] | 2019 | 28 | 4/(4) | 300 | Improved E/e´ ratio | ||

| Khan et al. [29] | 2020 | 123 | 0.14/(0.14) | 400 | Reduced BNPs and reduced time of hospitalisation | ||

| CoQ10 & Selenium | Kuklinski et al. [30] | 1994 | 61 | 52/(52) | 100 | Reduced cardiovascular mortality | 20.00 |

| Alehagen et al. [31••] | 2013 | 443 | 260/(520) | 200 | Improved echocardiogram, improved EF, reduced BNPs and reduced cardiovascular mortality | 6.70 | |

| Alehagen et al. [32] | 2015 | 443 | 260/(520) | 200 | Reduced cardiovascular mortality | 17.90 | |

| Alehagen et al. [33] | 2015 | 443 | 148/(270) | 200 | Reduced cardiovascular mortality | 3.50 | |

| Alehagen et al. [34] | 2016 | 668 | 208/(478.4) | 200 | Reduced cardiovascular mortality | 8.00 | |

| Alehagen et al. [35] | 2018 | 434 | 208/(832) | 200 | Reduced cardiovascular mortality | 10.60 | |

| Alehagen et al. [36] | 2021 | 213 | 208/(254) | 200 | Reduced cardiovascular mortality | 10.00 | |

| Opstad et al. [37] | 2022 | 118 | 42/(520) | 200 | Reduced cardiovascular mortality | 6.00 | |

| Alehagen et al. [38] | 2022 | 443 | 148/(148) | 200 | Improved echocardiogram, improved EF, reduced BNPs and reduced cardiovascular mortality | 6.70 | |

| CoQH2 | Orlando et al. [39] | 2020 | 50 | 2/(26) | 400 | Improved echocardiogram, improved EF, no reduced cardiovascular mortality | 0 |

| Kawashima et al. [40] | 2020 | 14 | 12/(12) | 400 | No improved echocardiogram and improved endothelial function | ||

| Holmberg et al. [41] | 2021 | 43 | 1/(1) | 600 | Improved EF and no reduced cardiovascular mortality | 0 | |

| Samuel et al. [42] | 2022 | 39 | 12/(12) | 300 | No Improved E/e´ratio and no reduced BNPs | ||

| CoQH2 & Ribose | Pierce et al. [43•] | 2022 | 216 | 12/(12) | 600 | Improved clinical status, improved EF, reduced BNPs and no reduced cardiovascular mortality | 0 |

Summarising results of Table 1 leads to three major outcomes: (I) the number of studies investigating the effect of CoQH2 on cardiovascular diseases is very limited; (II) In contrast to CoQ10, no CoQH2 study could clearly demonstrate a reduced cardiovascular mortality; (III) the used concentrations are much higher in studies investigating CoQH2.

According to these results, we conclude that based on the medical data available, CoQ10 is the more promising supplement to prevent cardiovascular diseases and to treat patients with heart failure. Further arguments for CoQ10 are the additive effect in combination with selenium [30, 31••] and the reduction of adverse effects of statin therapy by supplementation with CoQ10 [44–46]. Additionally, in all clinical trials included in this study, patients proceeded with their previous medication (statins, antihypertensives and others) and no interactions between CoQ10 and medicines could be observed.

At this point, it should be noticed that the Q-SYMBIO [25••] and KISEL-10 studies [31••] and their follow-up studies, all working on CoQ10, are the only clinical investigations clearly demonstrating a reduction in cardiovascular mortality in patients with heart failure over many years. Some studies working on CoQH2 are citing Q-SYMBIO and KISEL-10 studies to prove the cardiovascular effect of CoQH2 despite the fact that these studies are working on CoQ10 instead of CoQH2 [42]. Such misleading investigations are in detail discussed by Judy and Mantle [6, 10•].

Discussion

Even 30 years ago, studies recorded the beneficial effect of CoQ10 supplementation alone or in combination with selenium to improve EF [16], reduce time of hospitalisation [17] and reduce cardiovascular mortality in patients with heart failure [30]. In contrast to that, clinical trial investigation on the effect of CoQH2 on patients with heart failure started much later in 2020 [39] while investigations concerning antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of CoQH2 have been conducted in 1993 [47, 48]. This difference in medical evidence makes it challenging to compare CoQ10 and CoQH2 supplementation according to its usage to treat patients with cardiovascular disease and heart failure. Additionally, most CoQH2 studies used much higher concentrations than CoQ10 studies. CoQ10 studies included in this research test concentrations between 60 and 300 mg/day with one exception using 400 mg/day [29]. Studies with CoQ10 with selenium additive test between 100 and 200 mg/day. In contrast to that, CoQH2 studies included test concentrations between 300 and 600 mg/day. The only CoQH2 study using 300 mg/day test concentration included only 39 patients, and no beneficial cardiovascular effects could be observed [42].

Taking a closer look at major studies including at least 200 patients reveal extreme differences between CoQ10 and CoQH2. The group of Morisco et al. [17] reported a significant reduction in hospitalisation time in a study including 641 patients with heart failure and CoQ10 supplementation of 160 mg/day. The most cited Q-SYMBIO study of Mortensen et al. [25••] included 420 patients with heart failure and applied 3 × 100 mg of CoQ10 per day. After 2 years, a significant reduced time of hospitalisation and an improved NYHA class could be recorded. And most important, the cardiovascular mortality decreased by 18% compared to placebo group. KISEL-10 studies [31••] included 443 patients and applied 200 mg of CoQ10 per day combined with 200 µg of selenium. These studies focused on long-term effects of CoQ10 on cardiovascular mortality in patients with heart failure. They recorded a decrease of cardiovascular mortality of 17.9% after 10 years [32] and of 10.6% after 12 years [35]. In contrast to that, the CoQH2 study of Pierce et al. [43•] included 216 patients and applied 600 mg of CoQH2 per day in combination with 15 g/day of ribose. They recorded improved clinical status, improved EF and reduced BNPs values, but no reduction of cardiovascular mortality. According to the higher concentration (600 mg/day instead of 200 or 300 mg/day) used in CoQH2 studies and the weaker recorded benefit for patients with heart failure, the usage of CoQ10 supplementation is recommended in therapies of heart failure and cardiovascular disease in general.

Interestingly, there are differences in clinical outcomes of CoQ10 and CoQH2 despite the fact that CoQ10 can be converted to CoQH2 and vice versa in the human body by at least five enzymes [6]. Possible reasons are a different stomach transit [49] and duodenal absorption [50]. At this point, it should be stated that more pharmacological studies are needed to provide a clear answer to this question. Mantle et al. consider that many different cell types may have the capacity to reduce CoQ10 to CoQH2 in the external cellular environment. And if this is found to be the case, then presumably any of the various cell types lining the gastrointestinal tract would be able to facilitate this conversion, and the requirement for supplemental CoQH2 to maximise absorption would be negated [6]. Finally, it has to be noted that clear differences in clinical outcomes occur between CoQ10 and CoQH2.

Conclusion

As detailed above, our findings go along with the literature and the biochemical description of CoQ10 and CoQH2, recording cardiovascular benefits for CoQ10 and antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties for CoQH2 [7, 8]. It has to be noted that there is a lack of clinical relevant trials and misleading marketing claims associating CoQH2 with cardiovascular benefits [10•]. Comparing the work of Morisco et al. [17] and Q-SYMBIO, KISEL-10 studies [25••, 31••] with the study of Pierce et al. [43•] lead to the following outcomes: (I) CoQ10 supplementation alone or in combination with selenium reduced cardiovascular death in patients with heart failure. This is not recorded for CoQH2. (II) Test concentrations leading to cardiovascular benefits are much lower in CoQ10 studies than in CoQH2 studies. (III) Positive long-term effects are only observed in CoQ10 studies. In these studies, reduced cardiovascular mortality is recorded even after 12 years. Based on the existing literature, the authors recommend CoQ10 instead of CoQH2 to treat and prevent cardiovascular disease in patients with heart failure.

Author Contributions

All authors had full access to the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and study design as well as manuscript writing was performed by JPF. SG did the data preparation and conducted the table. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Graz. Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz.

Data Availability

Data and additional informations are available on request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

JPF reported receiving personal fees from Apomedica Pharmazeutische Produkte GmbH as part-time employee. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The funders had no role in the design of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.World Health Organization . Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013–2020 // Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases, 2013–2020. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Health Metrics Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, et al. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;118:3272–3287. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvac013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sue-Ling CB, Abel WM, Sue-Ling K. Coenzyme Q10 as adjunctive therapy for cardiovascular disease and hypertension: a systematic review. J Nutr. 2022;152:1666–1674. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxac079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linnane AW, Kios M, Vitetta L. Coenzyme Q(10)–its role as a prooxidant in the formation of superoxide anion/hydrogen peroxide and the regulation of the metabolome. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(Suppl):S51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantle D, Dybring A. Bioavailability of Coenzyme Q10: an overview of the absorption process and subsequent metabolism. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9. 10.3390/antiox9050386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Crane FL. Biochemical functions of coenzyme Q10. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:591–598. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Littarru GP, Tiano L. Bioenergetic and antioxidant properties of coenzyme Q10: recent developments. Mol Biotechnol. 2007;37:31–37. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0052-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yubero-Serrano EM, Gonzalez-Guardia L, Rangel-Zuñiga O, et al. Mediterranean diet supplemented with coenzyme Q10 modifies the expression of proinflammatory and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes in elderly men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:3–10. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judy WV. The instability of the lipid-soluble antioxidant ubiquinol: part 3–misleading marketing claims. Integr Med (Encinitas) 2021;20:24–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judy WV. The instability of the lipid-soluble antioxidant ubiquinol: part 2-dog studies. Integr Med (Encinitas) 2021;20:26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Judy WV. The instability of the lipid-soluble antioxidant ubiquinol: part 1-lab studies. Integr Med (Encinitas) 2021;20:24–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López-Lluch G, Del Pozo-Cruz J, Sánchez-Cuesta A, et al. Bioavailability of coenzyme Q10 supplements depends on carrier lipids and solubilization. Nutrition. 2019;57:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raizner AE, Quiñones MA. Coenzyme Q10 for patients with cardiovascular disease: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez-Mariscal FM, La Cruz-Ares S de, Torres-Peña JD et al. Coenzyme Q10 and cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10. 10.3390/antiox10060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Judy WV, Stogsdill WW, Folkers K. Myocardial preservation by therapy with coenzyme Q10 during heart surgery. Clin Investig. 1993;71:S155–S161. doi: 10.1007/BF00226859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morisco C, Trimarco B, Condorelli M. Effect of coenzyme Q10 therapy in patients with congestive heart failure: a long-term multicenter randomized study. Clin Investig. 1993;71:S134–S136. doi: 10.1007/BF00226854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chello M, Mastroroberto P, Romano R, et al. Protection by coenzyme Q10 from myocardial reperfusion injury during coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:1427–1432. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)91928-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morisco C, Nappi A, Argenziano L, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of cardiac hemodynamics during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: effects of short-term coenzyme Q10 treatment. Mol Aspects Med. 1994;15(Suppl):s155–s163. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh RB, Wander GS, Rastogi A, et al. Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of coenzyme Q10 in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1998;12:347–353. doi: 10.1023/a:1007764616025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berman M, Erman A, Ben-Gal T, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in patients with end-stage heart failure awaiting cardiac transplantation: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27:295–299. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960270512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chew GT, Watts GF, Davis TME, et al. Hemodynamic effects of fenofibrate and coenzyme Q10 in type 2 diabetic subjects with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1502–1509. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makhija N, Sendasgupta C, Kiran U, et al. The role of oral coenzyme Q10 in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;22:832–839. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuimov AD, Murzina TA. Coenzyme q10 in complex therapy of patients with ischemic heart disease. Kardiologiia. 2013;53:40–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortensen SA, Rosenfeldt F, Kumar A, et al. The effect of coenzyme Q10 on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure: results from Q-SYMBIO: a randomized double-blind trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aslanabadi N, Safaie N, Asgharzadeh Y, et al. The randomized clinical trial of coenzyme Q10 for the prevention of periprocedural myocardial injury following elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Ther. 2016;34:254–260. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mortensen AL, Rosenfeldt F, Filipiak KJ. Effect of coenzyme Q10 in Europeans with chronic heart failure: a sub-group analysis of the Q-SYMBIO randomized double-blind trial. Cardiol J. 2019;26:147–156. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2019.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobirin MA, Herry Y, Sofia SN, et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on diastolic function in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Drug Discov Ther. 2019;13:38–46. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2019.01004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan A, Johnson DK, Carlson S, et al. NT-Pro BNP predicts myocardial injury post-vascular surgery and is reduced with CoQ10: a randomized double-blind trial. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;64:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuklinski B, Weissenbacher E, Fähnrich A. Coenzyme Q10 and antioxidants in acute myocardial infarction. Mol Aspects Med. 1994;15(Suppl):s143–s147. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alehagen U, Johansson P, Björnstedt M, et al. Cardiovascular mortality and N-terminal-proBNP reduced after combined selenium and coenzyme Q10 supplementation: a 5-year prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial among elderly Swedish citizens. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1860–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alehagen U, Aaseth J, Johansson P. Reduced cardiovascular mortality 10 years after supplementation with selenium and Coenzyme Q10 for four years: follow-up results of a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial in elderly citizens. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0141641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alehagen U, Lindahl TL, Aaseth J, et al. Levels of sP-selectin and hs-CRP Decrease with dietary intervention with selenium and Coenzyme Q10 combined: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alehagen U, Alexander J, Aaseth J. Supplementation with selenium and Coenzyme Q10 reduces cardiovascular mortality in elderly with low selenium status. a secondary analysis of a randomised clinical trial. PLoS One 2016;11:e0157541. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Alehagen U, Aaseth J, Alexander J, et al. Still reduced cardiovascular mortality 12 years after supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10 for four years: a validation of previous 10-year follow-up results of a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial in elderly. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alehagen U, Aaseth J, Lindahl TL, et al. (2021) Dietary supplementation with selenium and Coenzyme Q10 prevents increase in plasma D-dimer while lowering cardiovascular mortality in an elderly Swedish population. Nutrients 2021;13. 10.3390/nu13041344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Opstad TB, Alexander J, Aaseth JO, et al. Selenium and Coenzyme Q10 intervention prevents telomere attrition, with association to reduced cardiovascular mortality-sub-study of a randomized clinical trial. Nutrients 2022;14. 10.3390/nu14163346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Alehagen U, Johansson P, Svensson E, et al. Improved cardiovascular health by supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10: applying structural equation modelling (SEM) to clinical outcomes and biomarkers to explore underlying mechanisms in a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled intervention project in Sweden. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61:3135–3148. doi: 10.1007/s00394-022-02876-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orlando P, Sabbatinelli J, Silvestri S, et al. Ubiquinol supplementation in elderly patients undergoing aortic valve replacement: biochemical and clinical aspects. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:15514–15531. 10.18632/aging.103742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Kawashima C, Matsuzawa Y, Konishi M, et al. Ubiquinol improves endothelial function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a single-center, randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover pilot study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020;20:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s40256-019-00384-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holmberg MJ, Andersen LW, Moskowitz A, et al. Ubiquinol (reduced coenzyme Q10) as a metabolic resuscitator in post-cardiac arrest: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Resuscitation. 2021;162:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samuel TY, Hasin T, Gotsman I, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in the treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drugs R D. 2022;22:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s40268-021-00372-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierce JD, Shen Q, Mahoney DE, et al. Effects of ubiquinol and/or D-ribose in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2022;176:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caso G, Kelly P, McNurlan MA, et al. Effect of coenzyme q10 on myopathic symptoms in patients treated with statins. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1409–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Derosa G, D'Angelo A, Maffioli P. Coenzyme q10 liquid supplementation in dyslipidemic subjects with statin-related clinical symptoms: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:3647–3655. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S223153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skarlovnik A, Janić M, Lunder M, et al. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation decreases statin-related mild-to-moderate muscle symptoms: a randomized clinical study. Med Sci Monit 2014;20:2183–2188. 10.12659/MSM.890777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Ernster L, Forsmark-Andrée P. Ubiquinol: an endogenous antioxidant in aerobic organisms. Clin Investig. 1993;71:S60–S65. doi: 10.1007/BF00226842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niki E. Mechanisms and dynamics of antioxidant action of ubiquinol. Mol Aspects Med. 1997;18(Suppl):S63–70. doi: 10.1016/S0098-2997(97)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Judy WV. Coenzyme Q10: an insider’s guide. 2018.

- 50.Wang TY, Liu M, Portincasa P, et al. New insights into the molecular mechanism of intestinal fatty acid absorption. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:1203–1223. doi: 10.1111/eci.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and additional informations are available on request.