Abstract

Previous studies have identified an N-terminal saliva-binding region (SBR) on Streptococcus mutans surface antigen I/II (AgI/II) and suggested its importance in the initial adherence of S. mutans to saliva-coated tooth surfaces and subsequent development of dental caries. In this study, we compared the SBR with a C-terminal structural region of AgI/II (AgII) in their abilities to induce protective immunity against caries in rats. When SBR, AgII, or the whole AgI/II molecule was administered intranasally as a conjugate with the B subunit of cholera toxin (CT), in the presence of CT adjuvant, substantial levels of salivary immunoglobulin A anti-AgI/II antibodies were induced. Evaluation of caries activity showed that the SBR, though not as protective as the parent molecule, was superior to AgII and thus can be further considered as a component in a multivalent caries vaccine.

Dental caries is an infectious disease in which Streptococcus mutans plays a major role. Although not life-threatening, this oral disease is among the most prevalent and costly in developing as well as industrialized countries (12, 19). An important first step in pathogenesis involves adherence of S. mutans to the saliva-coated tooth surfaces; adherence is mediated by a 185-kDa surface fibrillar protein referred to as surface antigen I/II (AgI/II), PAc, or P1 (2, 16). This adhesin has thus received attention as a target for immunological intervention against caries via salivary immunoglobulin A (IgA)-mediated inhibition of the initial adherence. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that human secretory IgA antibodies to AgI/II are capable of blocking the binding of S. mutans to saliva-coated hydroxyapatite (8). It has also been shown that intranasal (i.n.) immunization of rats with AgI/II, conjugated to the B subunit of cholera toxin (CT) for targeting and adjuvant action, induces specific salivary IgA antibodies and confers protection against caries development (10).

According to several reports from independent research groups (3, 6, 13), the functional domain of AgI/II responsible for initial adherence is localized on the N-terminal one-third of the molecule, which contains an alanine-rich repeat region. To render this saliva-binding region (SBR) immunogenic by mucosal routes of administration, we genetically linked the SBR with the A2 and B subunits of CT (SBR-CTA2/B) to construct a chimeric protein resembling CT in which the CT toxic A1 subunit was replaced by the SBR (5). Indeed, intragastric or i.n. immunization of mice with the SBR-CTA2/B chimeric protein induced T-cell-proliferative responses in mucosal inductive sites and long-lasting salivary IgA and serum IgG antibodies to the parent AgI/II molecule, even in the absence of adjuvants (5, 7, 20). More recently, it was reported that rabbit IgG antibodies against a PAc (AgI/II) segment within the SBR inhibit S. mutans adherence (22), further supporting the possibility that SBR contains protective epitopes.

The aim of this study was to determine whether the SBR can serve as a protective immunogen against dental caries development in a rat model. For comparison, we used another AgI/II segment, namely AgII, which represents the C-terminal and cell-surface-proximal region of the adhesin (17). On the native AgI/II molecule, the SBR and AgII are well separated by a segment of approximately 50 kDa. AgII is comparable in size to the SBR (AgII, 48 kDa; SBR, 42 kDa), but unlike the SBR, it does not contain adhesion epitopes (6). Thus, the present study was designed to determine the comparative protective potential of salivary IgA responses directed against either an adherence domain (SBR) or a structural region without any (known) functional significance (AgII).

Groups of germfree, 19-day-old Fischer rats were immunized by the i.n. route three times at 14-day intervals with 50 μg of SBR-CTA2/B chimeric protein, AgII-CT B, or AgI/II-CT B chemical conjugates (see below) in the presence of an adjuvant amount (1 μg) of CT (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, Calif.). These groups, as well as an unimmunized control group, were orally infected (on days 3, 4, and 5 after the initial immunization) with S. mutans UA130 and fed a cariogenic diet (10). The presence of S. mutans after infection was confirmed by microbiologic techniques (10). All groups consisted of five rats except for the AgI/II-CT B group, which contained four (however, one died before the termination of the experiment).

The immunogens used in this study were prepared as follows. SBR-CTA2/B was purified from Escherichia coli cell extracts by size-exclusion chromatography followed by anion-exchange chromatography, as previously described (5). Native AgI/II was chromatographically isolated from the culture supernatants of S. mutans IB162 (9), and part of the yield was digested with pronase to generate the protease-resistant AgII (17). Recombinant CT B (rCTB) was purified from periplasmic extracts of E. coli MTD9 (4) by galactose affinity chromatography (21). AgI/II and AgII were conjugated to rCTB by means of N-succinimidyl-(3-[2-pyridyl]-dithio)propionate (10).

To assess the antibody responses, serum and saliva samples were obtained 1 day before the initial immunization and at the termination of the experiment, i.e., 2 weeks after the last immunization (10). Moreover, at termination, mice were killed, and mandibles were removed, cleaned, stained with murexide, and hemisectioned for caries evaluation by the Keyes method, as previously described (10).

The levels of isotype-specific antibodies in serum and saliva and of total salivary IgA were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on microtiter plates coated with native AgI/II, recombinant SBR (isolated from E. coli lysates by metal-chelation chromatography [20]), AgII, GM1 ganglioside (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) followed by CT, or goat anti-rat IgA. Peroxidase-conjugated goat antibodies to the appropriate rat immunoglobulin isotype (IgG for serum samples and IgA for saliva samples) served as the developing reagents (all goat anti-rat antibodies were provided by Roger Lallone, Brookwood Biomedical, Birmingham, Ala.). The concentrations of antibodies and total IgA in test samples were calculated by interpolation on standard curves generated with a Fischer rat immunoglobulin reference serum (15), and data were expressed as geometric means ×/÷ standard deviations.

One-way analysis of variance in conjunction with the Bonferroni multiple-comparisons test (InStat program; GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.) was used for statistical evaluation of antibody response and caries activity data.

The requirement of intact CT as an adjuvant in this study was determined after a preliminary i.n. immunization experiment using rCTB conjugated with AgI/II or its SBR and AgII derivatives. Unexpectedly, rats responded very weakly or not at all in terms of serum and salivary antibodies to either the streptococcal antigens or rCTB. This unresponsiveness (at least by the Fischer strain of rats), which was reproduced in an additional experiment (data not shown), was somewhat surprising since rCTB is readily immunogenic by the i.n. route in mice (5, 21) and in humans (1). In a previous i.n. immunization study in which AgI/II-CT B conjugate was found to be immunogenic and protective in the Fischer rat model (10), CT B was obtained from a commercial source and contained traces of holotoxin. Therefore, to address the question of whether the SBR is also a protective immunogen against caries, we included 1 μg of CT adjuvant per dose for i.n. immunization of rats.

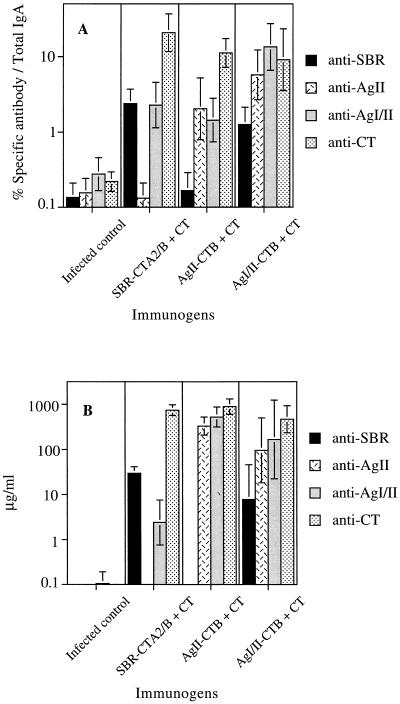

All immunized groups (SBR-CTA2/B, AgII-rCTB, and AgI/II-rCTB) generated salivary IgA and serum IgG responses to AgI/II (and CT) (Fig. 1A) at significantly higher levels (P < 0.01) than those seen in the unimmunized/infected control and in preimmune samples. Salivary IgA antibodies induced in the SBR-CTA2/B + CT immunized rats recognized SBR and the parent AgI/II molecule (specific antibody > 2% of total IgA) but not the AgII component (Fig. 1A). The converse was true after AgII-rCTB + CT immunization, i.e., salivary IgA antibodies reacted with the parent molecule and AgII, but essentially no reactivity to the SBR was seen (some background antibody activity is probably due to oral infection with S. mutans). The salivary IgA response induced by AgI/II-rCTB + CT was directed primarily to AgII rather than to SBR (Fig. 1A). Similar results were previously obtained in mice immunized with AgI/II-CT B chemical conjugates by the i.n. route, in that more than 60% of the salivary IgA anti-AgI/II antibody activity was directed against AgII and only about 10% was directed against the SBR (unpublished data). These findings are suggestive of antigenic competition, which might serve as a microbial protective mechanism whereby S. mutans directs the host response to a part of the AgI/II molecule that is not involved in adherence. Serum IgG responses to AgI/II and its components followed a pattern similar to that seen in saliva (Fig. 1B). AgII was more immunogenic than the SBR with regard to their respective abilities to induce serum IgG antibodies to the whole AgI/II or to themselves (P < 0.01). We then examined the effectiveness of the induced salivary IgA (and possibly serum IgG) antibodies in protection against S. mutans-induced caries, which should depend on both the magnitude and, more importantly, the epitope specificity of the response.

FIG. 1.

Levels of salivary IgA (A) and serum IgG (B) antibodies to SBR, AgII, AgI/II, and CT in unimmunized rats infected with S. mutans and in infected rats immunized by the i.n. route with SBR-CTA2/B, AgII-rCT B, or AgI/II-rCT B. Immunized animals were given three doses of the appropriate chimeric immunogen supplemented with CT adjuvant at 14-day intervals. Results are from samples collected two weeks after the last immunization and are expressed as the geometric means ×/÷ standard deviation.

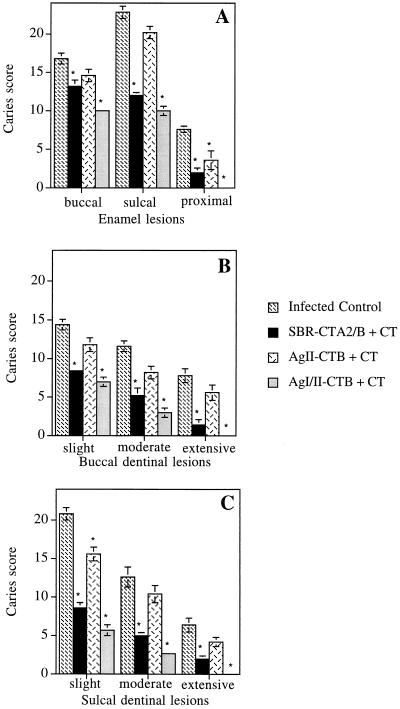

Rats immunized with AgI/II-rCTB + CT or SBR-CTA2/B + CT were significantly protected (P < 0.01) from dental caries compared with unimmunized controls (Fig. 2). This is in contrast to animals immunized with AgII-rCTB + CT, which generally did not show significant protection, except for the case of proximal enamel and sulcal dentinal slight lesions (P < 0.05). Essentially no proximal dentinal lesions were seen (data not shown), except for a few lesions in the unimmunized control and the AgII-rCTB + CT groups. The mean caries scores (Fig. 2) indicate that responses to the SBR did not inhibit caries activity to the same extent as those to AgI/II, although the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05), probably because of a limited number of animals in the AgI/II group. Nevertheless, this trend may reflect the in vitro observation that rabbit IgG antibodies to a PAc (AgI/II) segment which roughly corresponds to the SBR do not inhibit S. mutans adherence to the same extent as antibodies to the whole PAc molecule (22). Thus, it is likely that AgI/II contains additional protective adherence epitopes. In this regard, a segment of AgI/II encompassing the proline-rich repeat region (located approximately in the middle of the molecule) also suppresses the binding of S. mutans to saliva-coated hydroxyapatite (14). Interestingly, Scatchard analysis of AgI/II binding to saliva-coated hydroxyapatite suggested the presence of more than one binding site (6).

FIG. 2.

Caries activity on rat molar surfaces involving enamel (buccal, sulcal, and proximal surfaces) (A), buccal dentinal (B), and sulcal dentinal (C) lesions. Unimmunized rats and rats immunized by the i.n. route with SBR, AgII, or AgI/II (linked to rCTB and with CT as an adjuvant) were infected with S. mutans UA130 and fed a cariogenic diet. Values are the mean caries scores ± standard error of the means. The asterisks denote statistically significant differences from the unimmunized/infected control.

The finding that the SBR was in general a more protective immunogen than AgII was not surprising because of the SBR’s postulated functional significance as an adhesion domain in S. mutans infection. Limited caries inhibition in rats immunized with AgII could possibly be explained by anti-AgII antibody-mediated aggregation and clearance of S. mutans from saliva. An additional mechanism of protection against caries might be opsonization of S. mutans, with subsequent phagocytosis by polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the area of the tooth that is bathed with gingival crevicular fluid (18). In this respect, IgG antibodies to AgII are less opsonic than antibodies to AgI (18), which contains the SBR and constitutes the N-terminal two-thirds of AgI/II. It is also noteworthy that early experiments on systemic immunization of rhesus monkeys revealed that animals immunized with AgI/II or AgI developed fewer caries lesions than those immunized with AgII (11).

In summary, it appears that the SBR, although more protective than AgII, may not be capable of substituting for the whole AgI/II molecule in a caries vaccine. However, AgI/II appears to contain potentially harmful epitopes, which cross-react with human IgG, located at the C-terminal part of the molecule (13). On the other hand, no such presumably deleterious epitopes have been identified within the SBR. Our present results indicate that the SBR should be considered, along with other virulence factors (including those important at a later stage of the infection [for a review, see references 12 and 19]), as a component in a combined mucosal vaccine against dental caries. Such combination may result in an additive or synergistic effect and in greater protection against this oral disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cecily Harmon and Pam Smith for excellent technical assistance, Vickie Barron for secretarial assistance, and Roger Lallone for providing antibody reagents.

This study was supported by Public Health Service grants DE 09081, DE 08182, AI 33544, and DE06746.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergquist C, Johansson E-L, Lagergård T, Holmgren J, Rudin A. Intranasal vaccination of humans with recombinant cholera toxin B subunit induces systemic and local antibody responses in the upper respiratory tract and the vagina. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2676–2684. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2676-2684.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleiweis A S, Oyston P C F, Brady L J. Molecular, immunological, and functional characterization of the major surface adhesin of Streptococcus mutans. In: Ciardi J E, McGhee J R, Keith J, editors. Genetically engineered vaccines: prospects for oral disease prevention. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1992. pp. 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowley P J, Brady L J, Piacentini D A, Bleiweis A S. Identification of a salivary agglutinin-binding domain within cell surface adhesin P1 of Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1547–1552. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1547-1552.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dertzbaugh M T, Elson C O. Reduction in oral immunogenicity of cholera toxin B subunit by N-terminal peptide addition. Infect Immun. 1993;61:384–390. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.384-390.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajishengallis G, Hollingshead S K, Koga T, Russell M W. Mucosal immunization with a bacterial protein antigen genetically coupled to cholera toxin A2/B subunits. J Immunol. 1995;154:4322–4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajishengallis G, Koga T, Russell M W. Affinity and specificity of the interactions between Streptococcus mutans antigen I/II and salivary components. J Dent Res. 1994;73:1493–1502. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajishengallis G, Michalek S M, Russell M W. Persistence of serum and salivary antibody responses after oral immunization with a bacterial protein antigen genetically linked to the A2/B subunits of cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1996;64:665–667. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.665-667.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajishengallis G, Nikolova E, Russell M W. Inhibition of Streptococcus mutans adherence to saliva-coated hydroxyapatite by human secretory immunoglobulin A antibodies to the cell surface protein antigen I/II: reversal by IgA1 protease cleavage. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5057–5064. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5057-5064.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy L N, Knox K W, Brown R A, Wicken A J, Fitzgerald R J. Comparison of extracellular protein profiles of seven serotypes of mutans streptococci grown under controlled conditions. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:1389–1400. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-5-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz J, Harmon C C, Buckner G P, Richardson G J, Russell M W, Michalek S M. Protective salivary immunoglobulin A responses against Streptococcus mutans infection after intranasal immunization with S. mutans antigen I/II coupled to the B subunit of cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1964–1971. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1964-1971.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehner T, Russell M W, Caldwell J, Smith R. Immunization with purified protein antigens from Streptococcus mutans against dental caries in rhesus monkeys. Infect Immun. 1981;34:407–415. doi: 10.1128/iai.34.2.407-415.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michalek S M, Childers N K. Development and outlook for a caries vaccine. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1990;1:37–54. doi: 10.1177/10454411900010010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moisset A, Schatz N, Lepoivre Y, Amadio S, Wachsmann D, Schöller M, Klein J-P. Conservation of salivary glycoprotein-interacting and human immunoglobulin G-cross-reactive domains of antigen I/II in oral streptococci. Infect Immun. 1994;62:184–193. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.184-193.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munro G H, Evans P, Todryk S, Buckett P, Kelly C G, Lehner T. A protein fragment of streptococcal cell surface antigen I/II which prevents adhesion of Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4590–4598. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4590-4598.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redman T K, Harmon C C, Lallone R L, Michalek S M. Oral immunization with recombinant Salmonella typhimurium expressing surface protein antigen A of Streptococcus sobrinus: dose response and induction of protective humoral responses in rats. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2004–2011. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.2004-2011.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell M W. Immunization against dental caries. Curr Opin Dent. 1992;2:72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell M W, Bergmeier L A, Zanders E D, Lehner T. Protein antigens of Streptococcus mutans: purification and properties of a double antigen and its protease-resistant component. Infect Immun. 1980;28:486–493. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.2.486-493.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scully C M, Russell M W, Lehner T. Specificity of opsonising antibodies to Streptococcus mutans. Immunology. 1980;41:467–473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith D J, Taubman M A. Vaccines against dental caries infection. In: Levine M M, Woodrow G C, Kaper J B, Cobon G S, editors. New generation vaccines. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1997. pp. 913–930. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toida N, Hajishengallis G, Wu H-Y, Russell M W. Oral immunization with the saliva-binding region of Streptococcus mutans AgI/II genetically coupled to the cholera toxin B subunit elicits T-helper-cell responses in gut-associated lymphoid tissues. Infect Immun. 1997;65:909–915. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.909-915.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu H-Y, Russell M W. Induction of mucosal and systemic immune responses by intranasal immunization using recombinant cholera toxin B subunit as an adjuvant. Vaccine. 1998;16:286–292. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu H, Nakano Y, Yamashita Y, Oho T, Koga T. Effects of antibodies against cell surface protein antigen PAc-glucosyltransferase fusion proteins on glucan synthesis and cell adhesion of Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2292–2298. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2292-2298.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]