Abstract

Background:

While donor-specific antibody (DSA) pre- and post-transplantation is routinely assessed, accurate quantification of memory B cells that mediate recall antibody response remains challenging. MHC tetramers have been used to identify alloreactive B cells in mice and humans, but the specificity of this approach have not been rigorously assessed.

Methods:

BCR’s (B cell receptor) from tetramer binding single B cells were expressed as mouse recombinant IgG1 (rIgG1) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and the specificity were assessed by multiplex bead assay. Relative binding avidity of rIgG1 was measured by modified dilution series technique and surface plasmon resonance. In addition, IGHV (Immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region) of 50 individual BCR were sequenced to analyze the rate of somatic hypermutation.

Results:

Multiplex bead assay confirmed that expressed rIgG1 mAbs preferentially bound to bait MHC Class II I-Ed over control I-Ad and I-Ab tetramers. Furthermore, the KD50 binding avidities of the rIgG1 ranged from 10 mM to 7 nM. The majority of tetramer-binding B cells were low avidity, and ~12.8–15.2% from naïve and tolerant mice and 30.9% from acute rejecting mice were higher avidity (KD50<1 mM).

Conclusion:

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that donor MHC tetramers, under stringent binding conditions with decoy self-MHC tetramers, can specifically identify a broad repertoire of donor-specific B cells under conditions of rejection and tolerance.

INTRODUCTION

The low frequency of donor specific B cells in an endogenous polyclonal repertoire makes them challenging to identify and characterize their fate. Common approaches currently used to study antigen-specific B cells ex-vivo in humans and in pre-clinical models include a limit dilution assay followed by ex vivo differentiation of memory B cells into antibody-secreting cells, or bulk ex vivo differentiation of memory B cells followed by ELISA to assess anti-donor MHC antibodies in the supernatant or by ELISPOT assay to assess the frequency of donor MHC-specific B cells1–3. These approaches allow for the quantification of the frequency antigen specific memory B cells but is labor and resource intensive. The polyclonal activation of memory B cells in sensitized individuals followed by assessing antigen-specific antibody in the supernatant is less resource intensive but does not provide an accurate determination of the frequency of antigen-specific memory B cells4. In contrast, the antigen tetramer system in conjunction with flow cytometry has been used to identify antigen-specific B cells is a more direct measure of antigen-specific B cell frequency has been widely used to identify B cells specific to vaccine antigens and infections in human peripheral blood5. We and others have use of donor MHC tetramers to track donor reactive B cells in preclinical mouse transplantation models and also in humans, however concerns regarding the sensitivity and specificity of the MHC tetramer system remained incompletely resolved3,6,7.

Alloimmune injury in humans and pre-clinical models is mediated by T cells or antibodies8,9 that are generated by alloreactive B cells differentiating into cells producing anti-HLA antibody as well as serving as antigen-presenting cells to T cells1,12. Following antigen encounter, non-sensitized humans and mice, naïve B cells differentiate into antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) or memory B cells after receiving T cell help through germinal center-independent or dependent processes10,11,6. However, antigen reencounter in sensitized recipients results in rapid memory B cell differentiation into antibody-secreting cells, and with a small fraction of these memory B cells entering a secondary germinal center response3,6. It is notable that while ASCs and memory B cells may arise from the same naïve B cell, their BCR repertoires may not be identical since B cells with higher affinity differentiate preferentially into ASCs and those with lower affinity differentiating into memory B cells12,13. Furthermore, the loss of circulating antibodies and long-lived plasma cells may not reflect a concurrent loss in memory B cells14. Indeed, recent experimental studies showed that the quantification of donor-specific memory B cells in patients that lack detectable DSA can risk-stratify recipients for rejection and graft loss9,15. Although identifying donor MHC-reactive B cells and antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) remains challenging8,9, the ability to do so will complement DSA quantification to better characterize the humoral response in transplant recipients in addition to risk stratification16,17.

The use of MHC tetramers has revolutionized the study of allo-reactive T and B cells in preclinical models6,7. Specifically, we and others have used the tetramer baiting approach to characterize the fate of alloreactive B cells in transplant rejection and tolerance6,7,18. In those studies, approximately ~0.1% of endogenous polyclonal B cells from naïve mice bound to allogeneic MHC Class I or Class II, and only a modest >5-fold increase in B cell numbers were observed following sensitization with donor splenocytes (DSC) or with skin or heart allografts. This contrasted with a 10–20-fold increase in endogenous polyclonal CD4+ T cells19, and raised the possibility that the tetramer-binding B cell population may include B cells that were not donor-MHC-specific.

In this study we used a decoy self-MHC tetramer approach to identify donor MHC-specific B cells in naïve, rejecting and tolerant mice. The decoy self-MHC tetramer is generated by conjugating the streptavidin-phycoerythrin (SA-PE) to the AF647 fluorochrome to generate an emission detected by flow cytometry that is distinct from SA-PE. The SA-PE-AF646 then is tetramerized with biotinylated H-2Kb monomers, whereas the donor MHC-specific tetramer (H-2 I-Ed) is tetramerized to SA-PE. We then preincubated B cells with the decoy at six-fold higher concentrations higher than donor MHC tetramer to reduce non-specific binding to the bait unrelated to MHC I-Ed tetramer and also the B cells specifically binding to shared components of the tetramer, including SA-PE and biotin7. Using this approach, we show that this decoy tetramer approach identifies donor-MHC specific B cells with a high degree of specificity across a wide range of binding avidity in naïve, rejecting, and tolerant mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and Heart transplantation:

Eight- to 12-week-old female C57BL/6 (B6, H-2b) mice and 6- to 8-week-old female BALB/c (B/c, H-2d) mice were purchased from the Harlan laboratories. Heterotopic heart transplantations were performed as previously described20, by anastomosing donor B/c hearts to the inferior vena cava and aorta in the peritoneal cavity of female B6 recipients. Tolerance was induced with anti-CD154 (MR1, BioXCell) at a dose of 500 μg on day 0 (i.v), and 250 μg on days 7 and 14 (i.p) after transplantation, in combination with 2 × 107 donor spleen cells (DSC) on day 0. Rejection in untreated mice was defined as the last day of palpable heartbeat, which occurred between 7–10 days after surgery. All animals were housed in pathogen free conditions in accordance with University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Isolation of MHC Tetramer-binding B cells

Biotinylated I-Ed, I-Ad, I-Ab H-2Kb monomers, and PE-conjugated I-Ed tetramers were obtained from NIH tetramer core facility. Tetramers used were I-Ed presenting pCons-CDR1 (FIEWNKLRFRQGLEW), I-Ad presenting Staphylococcus aureus cysteine protease (GRDIHYQEGVPSYEQV) and H-2Kb presenting SIINFEKL. Decoy SIINFEKL:H-2Kb tetramers were generated in-house with the core fluorochrome, SA-PE (Prozyme), followed by conjugation to AF647 (Life Technologies) and incubation with biotinylated H2-Kb monomers, as described in Khiew et al.7 10 × 106 B cells were incubated with decoy tetramer (5 to 10 nM) prior to the addition of I-Ed-PE tetramer (5 nM).

B cells were enriched from brachial, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes from naïve, tolerant (post-operative day-30), and acute rejecting (post-operative day-14) WTB6 mice, while spleen B cells were excluded. Following Fc block (anti-CD16/32, S17011E/Biolegend) and Fixable Aqua Live/Dead staining (Thermo Fisher Scientific), single-cell suspensions of lymphocytes were incubated with H2-Kb decoy and I-Ed tetramers as previously described7. Antibodies used for surface staining at 4°C for B cells are CD19 (eBio1D3, Cat. 48-0193-82, eBioscience), B220 (RA3-6B2, Cat. 563103, BD Biosciences). Antibodies used to exclude non-B cells are CD4 (RM4–5, catalog 563106, BD Biosciences), CD8 (53–6.7, catalog 100706, Biolegend), CD49b (DX5, Cat. 485971–82, Invitrogen), CD11b (M1/70, Cat. 101224, Biolegend), CD11c (N418, Cat.48-0114-82), NK1.1(PK136, Cat. 48-5941-82), Ter-119 (Ter-119, Cat. 48-5921-82, eBioscience), F4/80 (BM8, Cat.48-4801-82, Invitrogen).

BCR cloning and recombinant IgG1 expression

As summarized in (Figure S1), single I-Ed -specific B cells were flow sorted (BD FACS Ariall 4–15) into 384 well plates containing hypotonic lysis buffer (10 nM TRIS and 0.75 units ml−1 of RNASin plus (Qiagen) and stored at −80 °C. Sorted single B cells were then subject to BCR cloning and expression as described in New et al. 202021. Briefly, cDNA was generated using the high-capacity cDNA generation kit (Applied Biosystems) followed by multiplexed PCR using primers specific for IGHV, IGKV, IGHC, and IGKC gene segments22. Semi-nested PCR was then used to amplify the rearranged Ig heavy and light chain genes and incorporated into mammalian expression plasmids containing the IGG1 or IGKC gene sequence. rIgG1 was generated by co-transfection of plasmids carrying the Ig heavy and light chain pairs into human embryonic kidney 293 freestyle cells, cultured for 5 days, and supernatants extracted for further analysis.

Multiplex bead assay to screen for supernatants for mIgG1, Kappa, and MHC specificity

Supernatants containing single BCR mAb from naïve, tolerant, and acute rejection were screened for IgG and MHC specificity at our laboratory. Multiplex streptavidin (SA) beads (PAK-5067–10K; Spherotech) were coated with biotinylated anti-mouse IgG Fab (1030–08, Southern Biotech), biotinylated anti-mouse kappa (1180–09, Southern Biotech) or biotinylated I-Ed, I-Ad or I-Ab monomers. Supernatants were incubated with pooled I-Ed, I-Ad, I-Ab coated beads at room temperature and then stained with PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 (1070–09; Southern Biotech). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of rIgG1 binding to the multiplex beads was determined by flow cytometer (LSRFortessa™ cell analyzer, BD Biosciences).

Defining KD50 of recombinant IgG1 by serial dilution

To determine the relative avidity of rIgG1 by dilution series, supernatants containing rIgG1 were serially diluted 7 times (3-fold dilution) and incubated with I-Ed-coated beads, followed by PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 (1070–09, Southern Biotech). A standard curve was generated between the concentration of IgG1/Kappa bound on the SA beads and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 (1070–02/Southern/Biotech). SA beads were coated with biotinylated anti-mouse Kappa (1050–08/SouthernBiotech), and then incubated with five dilutions of known concentrations of IgG1/Kappa (murine myeloma MOPC 31C; Cat: M9035, Sigma Aldrich), followed by incubation with PE-conjugated anti-mouse Kappa (1050–09, Southern Biotech). The rIgG1 concentrations in the supernatant were calculated, and KD50 values of rIgG1 binding to I-Ed tetramers were determined by Scatchard Plot using nonlinear regression (one site binding model) on GraphPad Prism software.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

SPR was performed on a GE Biocore 8K SPR instrument (General Electronic) in the Biophysics core at the University of Chicago. Series S sensor chip (Cytiva) was immobilized with biotinylated I-Ed monomers. Supernatants of rIgG1 were diluted to 1nM, 2.5nM, 5nM, 10nM and 15nM in HEPES buffered saline and loaded into a 96-well plate. Supernatants containing rIgG1 were run over the chip for 180 s, followed by a 900 s dissociation step. Association constant (KA) and dissociation constant (KD) calculations were determined using the Biacore analysis software.

BCR sequencing

DH5-alpha cells (Invitrogen, Cat. 12297016) were transfected with cloned Ig heavy chain plasmids, and transfected cells were positively selected in kanamycin media (Millipore Sigma Cat. L0543). Presence of heavy chain inserted plasmids were screened by PCR, using sequencing primers (Forward: SP6 5’ ATTTAGGTGACACTATAG 3’; Reverse: mIgH ACC AGG CAT CCC AGG GTC ACC). Clones of interest were expanded, and plasmids were isolated by miniprep plasmid isolation kit (QIAgen). Plasmids were sequenced in University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center DNA sequencing facility. NIH IgBLAST and IMGT website tools were used to analyze V/D/J genes and CDRH-3 length.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism version 9. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test and Two-tailed Wilcoxon matched- pairs signed rank test were performed to determine significance of difference between groups. Simple linear regression was performed to assess the correlation between N-MFI ratio, serial dilution, and SPR. P values below 0.05 were considered to indicate significant difference: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

RESULTS

Monoclonal antibody expressed from a single I-Ed BCR clone preferentially binds to multiplex beads coated with I-Ed antigen.

To assess the specificity of the tetramers, B cells were isolated from the lymph nodes of naïve B6, and B6 recipients of B/c hearts undergoing acute rejection or acquired tolerance following treatment with anti-CD154/DSC. These B cells were then incubated with decoy followed by I-Ed tetramers. Consistent with previous reports, the frequency of I-Ed tetramer-binding naïve and tolerant B cells ranged from 0.1–0.2%, and from 0.3–0.5% for acute rejecting B cells7, and the frequency that were class-switched for naïve and tolerant was 5–7% and 15–20% for acute rejection7. I-Ed tetramer-binding and decoy-negative CD19+ B cells were flow-sorted as single B cell/well, and the Ig heavy and light chain pairs from individual B cells were cloned and expressed as recombinant rIgG1/kappa (Figure S1).

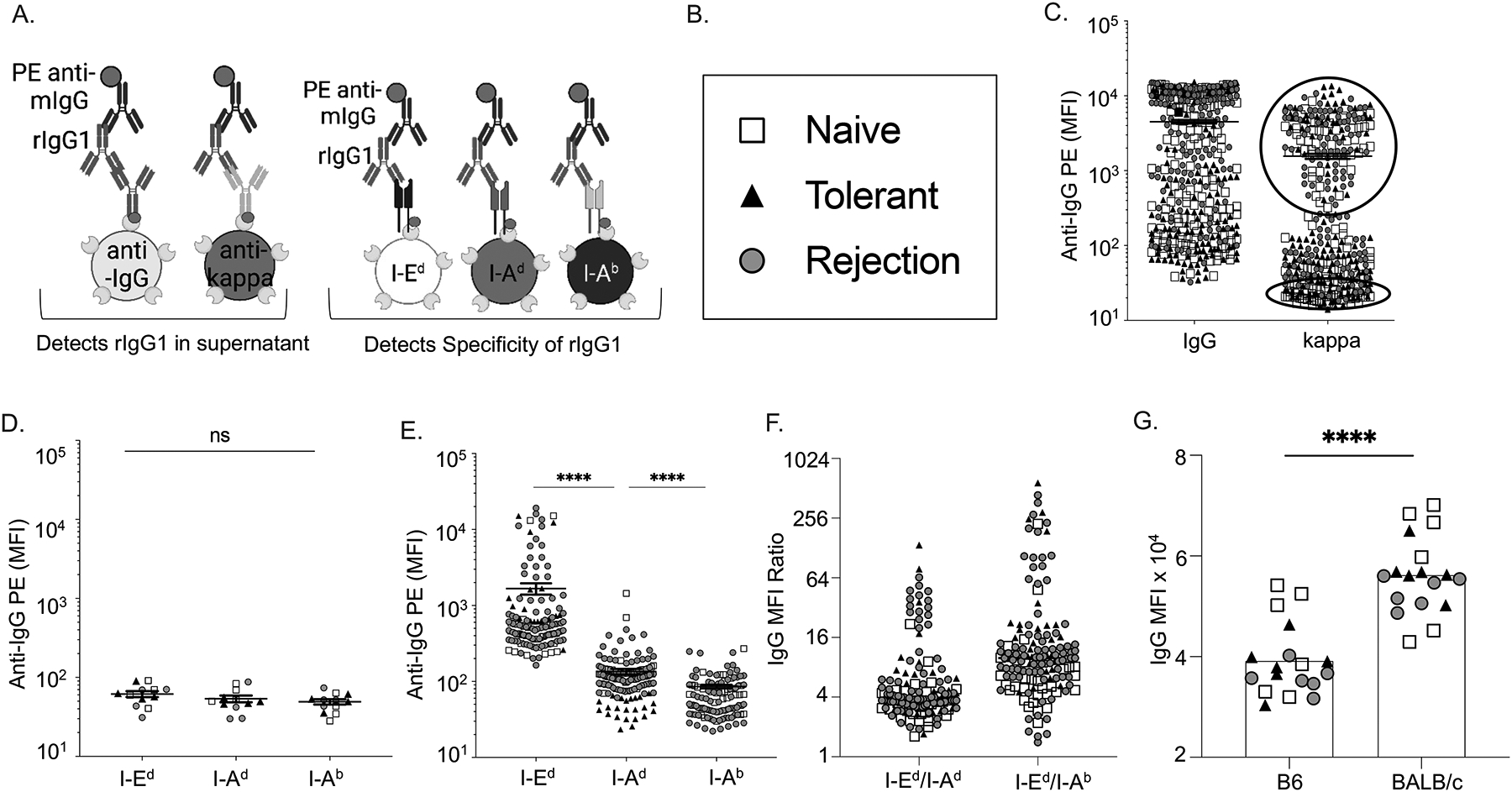

A multiplex bead assay was used to simultaneously assess the concentration of rIgG1 and kappa in supernatants of individual BCR clones and the specificity of each rIgG1 (Figure 1A). A total of 415 clones were assessed from naïve, rejecting or tolerant mice, with a range of IgG and kappa concentrations detected. Overall, the cloning efficiency was estimated to be 52–81% based on a kappa MFI cutoff of 450 (Figure 1B,C; Table 1; Figure S2A–C), with higher cloning efficiencies in rejection compared to naïve or tolerant mice (Table 1). The background MFI of the beads in the absence of supernatant ranged between 170–390, and supernatants with kappa MFI <450 were considered to have minimal rIgG1 and served as negative controls (Figure 1D). Supernatants with kappa MFI>2500 were analyzed and shown to bind to I-Ed-coated beads with higher MFI compared to I-Ab- or I-Ad-coated beads (Figure 1E; P value: <0.0001). Furthermore, normalized ratios of clones with MFI>2500 for I-Ed vs I-Ad or I-Ab confirmed that I-Ed tetramer-binding B cells expressed BCRs that bound preferentially to I-Ed (Figure 1F). Supernatants containing rIgG1 that preferentially bound to I-Ed-coated beads also bound to CD19+ B/c splenocytes, in the presence of blocking anti-CD16/32 IgG (Figure 1G). Collectively, these data demonstrate that I-Ed tetramers were able to preferentially bind to anti-I-Ed B cells from naïve, tolerant and rejecting mice.

Figure 1. Recombinant IgG1 cloned from single I-Ed tetramer-binding B cells preferentially bound to I-Ed–coated beads and B/c splenocytes.

(A) Schematics of multiplex bead assay using streptavidin-coated beads displaying biotinylated anti-mouse IgG or anti-mouse kappa, and donor I-Ed, donor I-Ad or self I-Ab antigens. (C) Relative concentrations of mouse IgG1 and kappa in the culture supernatants of single BCR clones detected with PE-anti-IgG and presented as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Each symbol represents one rIgG1 cloned from single B cells from naïve, rejecting or tolerant mice. (D-E) Supernatants with low (bottom circle 1C) or high (Top circle 1C) kappa concentrations binding to beads coated with I-Ed, I-Ad, or I-Ab, and presented as relative MFI. (F) Normalized MFI ratio confirms that rIgG1 expressed from I-Ed tetramer-binding B cells preferentially binds to I-Ed beads compared to I-Ad, or I-Ab. (G) rIgG1 binds to B/c B cells (CD19+) in the presence of blocking anti-CD16/32.

Table 1:

Cloning efficiency of single I-Ed- tetramer binding B cells

| Cloned B Cell | Naive | Tolerant | Acute Rejection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Clones Screened | 142 | 130 | 143 |

| # IgG-positive Clones (% Positive) | 124 (86%) | 96 (74%) | 136 (95%) |

| MFI ± SEM for IgG

(min-max) |

38202 ±

46144 (384–141692) |

38494 ±

53659 (344–151866) |

59026 ± 50540

(325–149989) |

| # kappa-positive Clones (% Positive) | 74 (52%) | 78 (60%) | 116 (81%) |

| MFI for kappa (min-max) |

10502 ±

16859 (159–84632) |

16825 ±

29852 (140–134577) |

21556±25331 (183–107808) |

Cutoff MFI for IgG-positive supernatants was 900

Cutoff MFI for kappa-positive supernatants was 450

I-Ed specific tetramers identify alloreactive B cells with a wide range of binding avidity.

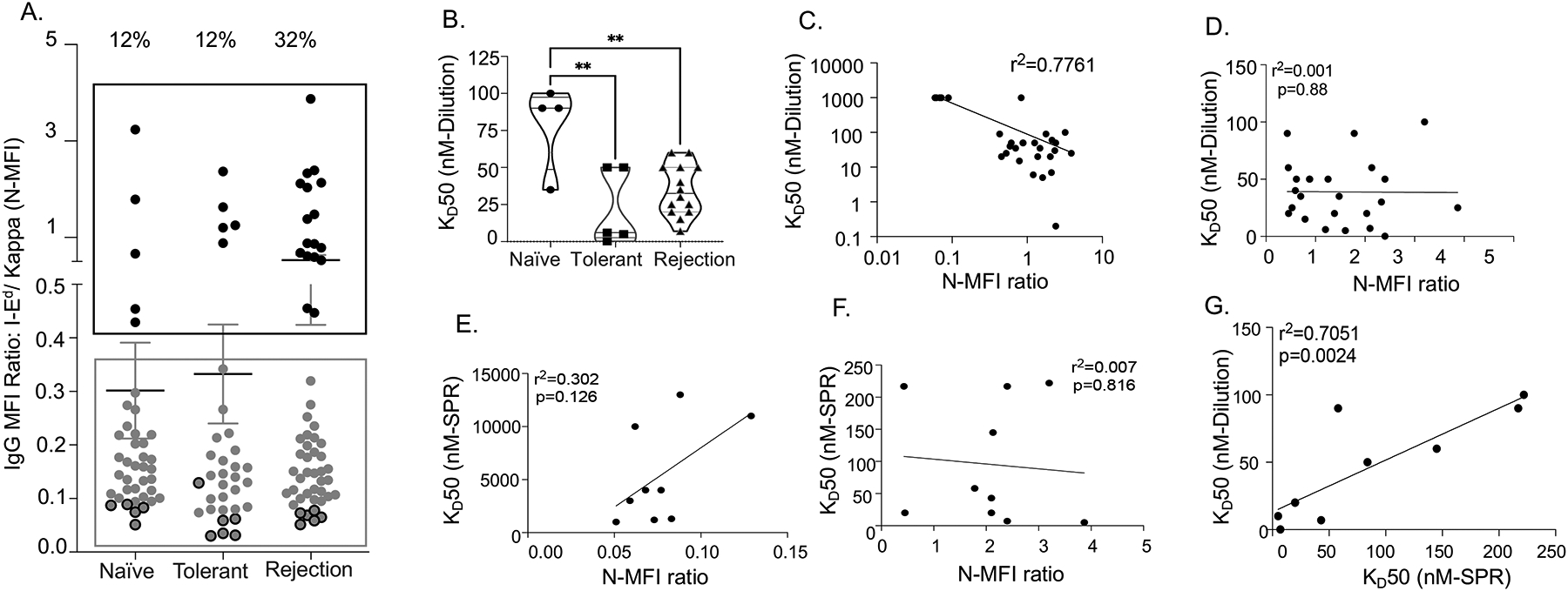

The wide range of MFI for rIgG1 binding to I-Ed beads could reflect rIgG1 concentration in the supernatant or avidity of the rIgG1. As an initial attempt to address these possibilities, we calculated normalized MFI (N-MFI) for each rIgG1 by dividing the MFI of I-Ed beads with the MFI of anti-kappa IgG beads. As shown in Figure 2A, N-MFI divided the supernatants into two distinct groups, where ratios >0.43 were considered to be higher avidity and ratios <0.4 were considered as lower avidity rIgG1. As expected, the percentage of high avidity clones was higher in the rejection group (32%) compared to the naïve (12%) and tolerant (12%) groups.

Figure 2. I-Ed tetramers identify BCRs with a broad range of avidity from naïve, tolerant, and rejecting mice.

(A) Normalized-MFI (N-MFI) ratios (I-Ed/Kappa): ratios >0.43 (Black box) categorized rIgG1 as high binding avidity and ratios <0.4 (Grey box) as low binding avidity. Binding avidity of all high avidity clones and several low avidity clones (dark grey dots) were further tested in dilution series and by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). (B) Based on KD50 in dilution series, the frequency of high avidity clones was higher in tolerant and rejection mice compared to naïve. (C) Significant correlation between N-MFI ratios and KD50 by dilution series among all clones. (D) No significant correlation between N-MFI ratios (>0.43) and KD50 by dilution series among the high/intermediate avidity clones. (E) Weak correlation between KD50 values determined by SPR vs. N-MFI ratios (<0.4) for low avidity clones. (F) No significant correlation between KD50 value determined by SPR and N-MFI ratios (>0.4) for high avidity clones. (G) KD50 values determined by SPR correlate with KD50 values by serial dilution for higher avidity clones.

To test if N-MFI ratios accurately categorized the relative avidities of rIgG1, we defined their equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) using a modified serial dilution approach, and where KD50 was defined as 50% of maximum binding (Figure S3). For the 23 randomly selected clones with N-MFI ratio >0.43, the KD50 ranged from 30–100nM for naïve, 0.2–50 nM for tolerant, and 7nM-60nM for rejection, consistent with these clones being of high/intermediate avidity (Fig 2B). In contrast, for the 6 rIgG1 clones with N-MFI ratios <0.4, the KD50 was ≥1 μM, consistent with low avidity clones (Figure S3B). Overall, there was a correlation between KD50 value and N-MFI among all clones, and that N-MFI was able to broadly able to distinguish between high and low avidity clones (Figure 2C). However, the correlation between the KD50 and N-MFI for the high vs intermediate avidity clones was not statistically significant (Figure 2D), suggesting that N-MFI was not sufficiently accurate to distinguish more subtle differences in avidity.

To confirm that KD50 values assessed by dilution series were an accurate measure of avidity, we next measured KD50 of 19 rIgG1 clones by SPR23, the gold standard to measure avidity (Figure S4). SPR was able to distinguish between the low avidity clones with N-MFI <0.4 and showed that they had KD50 that ranged from 1–10 μM (Figure 2E). Thus, while N-MFI ratios were able to broadly distinguish the low affinity from high/intermediate affinity rIgG1, they could not distinguish between the high and intermediate avidity rIgG1 (Fig 2F). Finally, the KD50 by SPR analysis strongly correlated with KD50 by dilution series (R2=0.705; Fig 2G) amongst the high and intermediate rIgG1 but did not correlate with N-MFI ratios.

High-avidity heavy chain clones are not the result of affinity maturation but emerge Spontaneously.

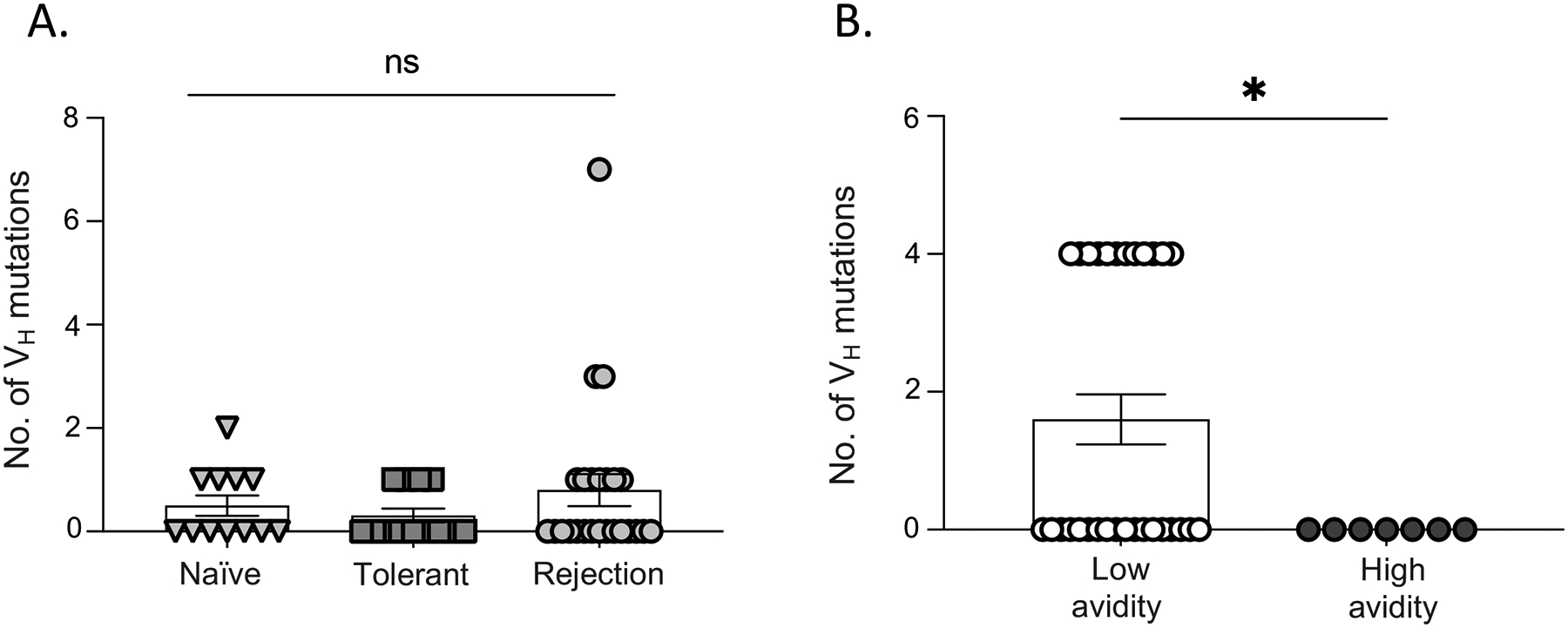

Fifty BCR clones across the experimental groups based on high, intermediate and low avidities (KD50<10nM, <100nM, >100nM, respectively) were randomly selected, and the IGHV were sequenced, and mutation rates analyzed to assess the correlation between the mutation burden, immunological state, and BCR avidity. Contrary to expectation, there was no significant difference between the mutation rates (non-silent and silent) in B cells from naïve (n=12), tolerant (n=13) or acute rejection (n=25) mice (Figure 3A). When we compared the mutation rates with respect to the avidity, irrespective of experimental groups, the mutation rates in low avidity clones were unexpectedly, significantly higher (p=0.0296) than high-avidity clones (Figure 3B). Furthermore, among the 50 BCR clones, only one pair of IGHV were clonally related suggesting only modest expansion and mutation rates in rejecting mice by the time of acute rejection.

Figure 3. Mutation rates of anti-I-Ed BCR sequences in naïve, tolerant, and acute rejection.

(A) The number of silent and non-silent mutation rates of Ig heavy chains are not statistically significant between naïve, tolerant, and acute rejection. (B) Low avidity clones had higher mutation rates irrespective of the immunological state of the mice.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that MHC tetramers can identifies donor MHC-reactive B cells with a high degree of specificity and across a wide range of binding avidities from naïve, tolerant, and rejecting mice. By utilizing three methods to assess the avidity, we show that N-MFI ratios broadly distinguish high from low avidity clones. It is possible that a saturating prozone effect may have contributed to the relatively poor ability of normalized MFI ratios to discriminate the high and intermediate avidity rIgG1. To distinguish between high/intermediate avidity clones, KD50 values determined by serial dilution were comparable with SPR, whereas SPR is the approach of choice for low avidity clones. Serial dilution is experimentally easier than SPR and thus can be used as a reliable way to both identify and quantify the KD50 values of high/intermediate avidity IgG. Furthermore, BCR sequencing revealing low mutation levels suggesting that MHC specific high avidity B cells are stochastically generated in naive mice, with that rejection favoring expansion of higher avidity clones. Notably, at the time of acute rejection of full-mismatched heart allografts, only limited clonal expansion and accumulation of mutations were observed. It is possible that at a later time following transplantation, higher affinity B cells can be detected with greater levels of mutations emerging from the germinal center response. However, the observation that a range of avidities for allogeneic MHC already exists in the naïve repertoire is important.

The demonstration that the approach specifically identifies donor MHC-specific B cells in mouse transplant models, raises the possibility that this approach could be applied to identify HLA-reactive B cells and can serve as a biomarker for rejection if performed under rigorous staining conditions to reduce non-specific binding. While decoy tetramers comprising recipient HLA alleles will rigorously exclude B cells recognizing non-HLA components in the tetramer, the simpler single tetramer-double fluorochrome approach can also considerably exclude fluorochrome reactive B cells. This latter approach may be sufficiently specific for identifying HLA-reactive B cells during rejection where there is significant clonal expansion7. For example, there is growing evidence of the detrimental impact of HLA-DQ mismatch on allograft survival24,25, thus identifying the repertoire of HLA-DQ reactive B cells prior to and after transplantation may help decipher the immunogenicity of specific HLA-DQ alleles. In contrast to rejection, B cell expansion may not occur in stable immunosuppressed recipients or unsensitized transplant candidates, so identifying donor HLA-specific B cells in such recipients and unsensitized recipients may require the more rigorous decoy approach using self HLA as decoys7. Furthermore, several groups have reported the enrichment of transitional B cells with regulatory potential in patients developing operational tolerance following kidney transplant, and raised the possibility that they may be useful biomarkers for predicting allograft outcome26,27,28. We posit that the decoy HLA tetramer approach may be useful to investigate if these regulatory B cells are donor HLA-specific, and thus provide additional insights into how these B cells may facilitate the development or maintenance of operational tolerance in clinical transplantation.

In summary, we show that MHC tetramers can specifically identify donor MHC-specific B cells with a broad range of binding avidities from naïve, tolerant, and rejecting mice. Moving forward, MHC or HLA tetramers can be confidently utilized for mechanistic and functional characterization of alloreactive B cells in both pre-clinical models and humans, either before or after solid organ transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) to ASC (R01AI142747, R01AI148705, P01AI097113).

Abbreviations

- ASC

Antibody-secreting cells

- BCR

B cell receptor

- CDR

complementarity-determining region

- DSA

Donor-specific antibody

- DSC

Donor spleen cells

- HLA

Human leucocyte antigen

- IGHV

Immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region

- KD

Dissociation constant

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- MFI

Mean fluorescence intensity

- mAbs

Monoclonal antibodies

- N-MFI

Normalized- Mean fluorescence intensity

- rIgG1

Recombinant IgG1

- SA

Streptavidin

- SPR

Surface plasmon resonance

Footnotes

Competing Interests:

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Blanchard-Rohner G, Galli G, Clutterbuck EA, et al. Comparison of a limiting dilution assay and ELISpot for detection of memory B-cells before and after immunisation with a protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine in children. J Immunol Methods. Jun 30 2010;358(1–2):46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saletti G, Cuburu N, Yang JS, et al. Enzyme-linked immunospot assays for direct ex vivo measurement of vaccine-induced human humoral immune responses in blood. Nat Protoc. Jun 2013;8(6):1073–87. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang J, Chen J, Young JS, et al. Tracing Donor-MHC Class II Reactive B cells in Mouse Cardiac Transplantation: Delayed CTLA4-Ig Treatment Prevents Memory Alloreactive B-Cell Generation. Transplantation. Aug 2016;100(8):1683–91. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karahan GE, Krop J, Wehmeier C, et al. An Easy and Sensitive Method to Profile the Antibody Specificities of HLA-specific Memory B Cells. Transplantation. Apr 2019;103(4):716–723. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tjiam MC, Fernandez S, French MA. Characterising the Phenotypic Diversity of Antigen-Specific Memory B Cells Before and After Vaccination. Front Immunol. 2021;12:738123. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.738123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Wang Q, Yin D, et al. Cutting Edge: CTLA-4Ig Inhibits Memory B Cell Responses and Promotes Allograft Survival in Sensitized Recipients. J Immunol. Nov 1 2015;195(9):4069–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khiew SH, Jain D, Chen J, et al. Transplantation tolerance modifies donor-specific B cell fate to suppress de novo alloreactive B cells. J Clin Invest. Jul 1 2020;130(7):3453–3466. doi: 10.1172/JCI132814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loupy A, Lefaucheur C. Antibody-Mediated Rejection of Solid-Organ Allografts. N Engl J Med. Sep 20 2018;379(12):1150–1160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1802677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luque S, Lucia M, Melilli E, et al. Value of monitoring circulating donor-reactive memory B cells to characterize antibody-mediated rejection after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. Feb 2019;19(2):368–380. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laidlaw BJ, Cyster JG. Transcriptional regulation of memory B cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. Apr 2021;21(4):209–220. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00446-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nutt SL, Hodgkin PD, Tarlinton DM, et al. The generation of antibody-secreting plasma cells. Nat Rev Immunol. Mar 2015;15(3):160–71. doi: 10.1038/nri3795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffman RL, Lebman DA, Rothman P. Mechanism and regulation of immunoglobulin isotype switching. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:229–70. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60536-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ochiai K, Maienschein-Cline M, Simonetti G, et al. Transcriptional regulation of germinal center B and plasma cell fates by dynamical control of IRF4. Immunity. May 23 2013;38(5):918–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavinder JJ, Horton AP, Georgiou G, et al. Next-generation sequencing and protein mass spectrometry for the comprehensive analysis of human cellular and serum antibody repertoires. Curr Opin Chem Biol. Feb 2015;24:112–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wehmeier C, Karahan GE, Heidt S. HLA-specific memory B-cell detection in kidney transplantation: Insights and future challenges. Int J Immunogenet. Jun 2020;47(3):227–234. doi: 10.1111/iji.12493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sablik KA, Clahsen-van Groningen MC, Looman CWN, et al. Chronic-active antibody-mediated rejection with or without donor-specific antibodies has similar histomorphology and clinical outcome - a retrospective study. Transpl Int. Aug 2018;31(8):900–908. doi: 10.1111/tri.13154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opelz G Non-HLA transplantation immunity revealed by lymphocytotoxic antibodies. The Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1570–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwun J, Oh BC, Gibby AC, et al. Patterns of de novo allo B cells and antibody formation in chronic cardiac allograft rejection after alemtuzumab treatment. Am J Transplant. Oct 2012;12(10):2641–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04181.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller ML, McIntosh CM, Williams JB, et al. Distinct Graft-Specific TCR Avidity Profiles during Acute Rejection and Tolerance. Cell Rep. Aug 21 2018;24(8):2112–2126. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young JS, Chen J, Miller ML, et al. Delayed Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4-Immunoglobulin Treatment Reverses Ongoing Alloantibody Responses and Rescues Allografts From Acute Rejection. Am J Transplant. Aug 2016;16(8):2312–23. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.New JS, Dizon BLP, Fucile CF, et al. Neonatal Exposure to Commensal-Bacteria-Derived Antigens Directs Polysaccharide-Specific B-1 B Cell Repertoire Development. Immunity. Jul 14 2020;53(1):172–186 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiller T, Busse CE, Wardemann H. Cloning and expression of murine Ig genes from single B cells. J Immunol Methods. Oct 31 2009;350(1–2):183–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen HH, Park J, Kang S, et al. Surface plasmon resonance: a versatile technique for biosensor applications. Sensors (Basel). May 5 2015;15(5):10481–510. doi: 10.3390/s150510481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willicombe M, Brookes P, Sergeant R, et al. De novo DQ donor-specific antibodies are associated with a significant risk of antibody-mediated rejection and transplant glomerulopathy. Transplantation. Jul 27 2012;94(2):172–7. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182543950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Senev A, Coemans M, Lerut E, et al. Eplet Mismatch Load and De Novo Occurrence of Donor-Specific Anti-HLA Antibodies, Rejection, and Graft Failure after Kidney Transplantation: An Observational Cohort Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. Sep 2020;31(9):2193–2204. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020010019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lozano JJ, Pallier A, Martinez-Llordella M, et al. Comparison of transcriptional and blood cell-phenotypic markers between operationally tolerant liver and kidney recipients. Am J Transplant. Sep 2011;11(9):1916–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cherukuri A, Rothstein DM, Clark B, et al. Immunologic human renal allograft injury associates with an altered IL-10/TNF-alpha expression ratio in regulatory B cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. Jul 2014;25(7):1575–85. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherukuri A, Rothstein DM. Regulatory and transitional B cells: potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in organ transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. Aug 10 2022;doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000001010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.