The annual grass foxtail millet (Setaria italica) was first domesticated ∼11 000 years ago, making it one of the most ancient crops in the world, and it was the mainstay underpinning the development of Asian farming civilization. The looming food shortage crisis, aggravated by climate change, threatens to make current agriculture unsustainable. As a C4 photosynthetic plant, foxtail millet has attracted increasing attention from the scientific and industrial farming communities because of its drought tolerance, good adaptability, and nutritional properties. Foxtail millet and green foxtail (Setaria viridis) have been developed into ideal model systems for C4 crops owing to their compact diploid genomes, rich genetic diversity, self-pollination, high-throughput transformation, short life cycles, and ease of laboratory culture.

Over the past half century, the grain yields of staple food crops such as rice, wheat, and maize have increased greatly, mainly because of advances in genetics and breeding. By comparison, our understanding of the molecular genetics of foxtail millet is nowhere near as advanced. Draft genome sequences for foxtail millet were first generated in 2012, and regions of differential SNP density, transposable element distribution, small RNA content, chromosomal rearrangement, and segregation distortion were identified. These sequences can be used to reveal the evolution of C4 photosynthesis and facilitate mapping of important quantitative traits (Bennetzen et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). Jia et al. (2013) sequenced the genomes of 916 diverse foxtail millet germplasms, identified 2.58 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), constructed a haplotype map of the genome, and identified 512 loci associated with 47 agronomic traits by genome-wide association studies (GWASs). With the development of advanced sequencing technology, a higher-quality genome sequence of foxtail millet was assembled using the dwarf mutant “xiaomi”. The life cycle of this mutant is similar in length to that of Arabidopsis, and an efficient transformation system has been established, making it an ideal model system for C4 cereals (Yang et al., 2020). Mamidi et al. (2020) produced a high-quality genome assembly of S. viridis and de novo assemblies for 598 wild accessions, enabling the identification of several loci underlying domestication and yield traits. A comprehensive multi-omics analysis of foxtail millet genomes, transcriptomes, metabolomes, and anti-inflammatory indices revealed the genetic mechanism of directional metabolite changes during domestication selection (Li et al., 2022). In 2023, the International Year of Millets designated by the FAO, He et al. (2023) established a graph-based pan-genome of foxtail millet and constructed a functional gene mining platform that enabled identification of several key genes, demonstrating the advantages of this system (Figure 1). The genetic variations revealed in this pan-genome are much more extensive than those of previously published foxtail millet genomes because previous versions were constructed primarily from short-read DNA sequencing data or long-read DNA sequencing data with smaller sample sizes. These advances are significant for systematic and fundamental research on population evolution, genome structure polymorphism, environmental adaptability, domestication, and improvement, as well as applied aspects of foxtail millet agronomy.

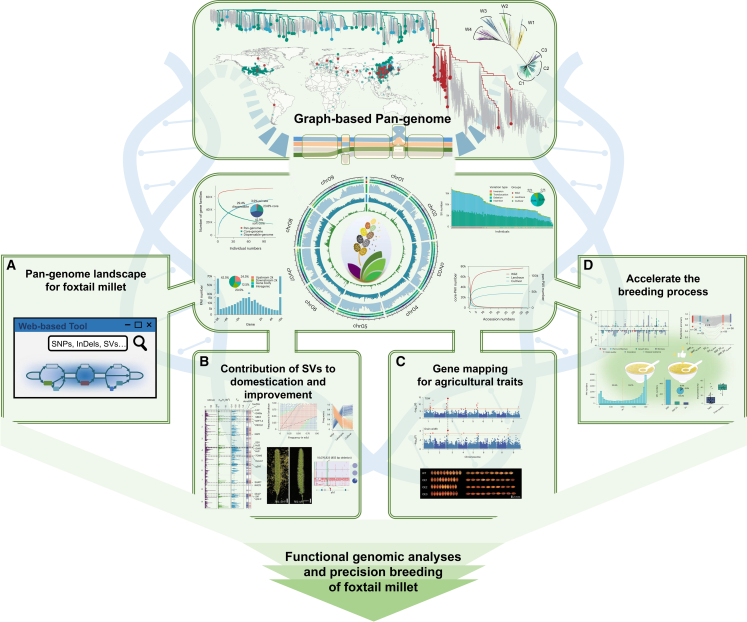

Figure 1.

Pan-genome of foxtail millet and its applications.

A graph-based pan-genome is a way to store all the genetic information of a species in a graphical format in which variations in sequence and structure are shown in the form of nodes and paths. It performs phasing directly in the space of sequence graphs, without flattening them into contigs in intermediate steps. He et al. collected genome-wide resequencing data for 630 wild (S. viridis), 829 landrace, and 385 modern cultivated accessions from the Setaria genus. Wild species were classified into four subgroups (W1–W4), and cultivars were classified into three genetically differentiated subpopulations (C1–C3). The 110 high-quality genome sequences, representing accessions of both wild and cultivated types, are important resources for functional genomic analyses and precision breeding of foxtail millet. There are four main directions for the application of pan-genomics to foxtail millet breeding: (A) development of tools to access and explore these genomic resources via an online pan-genome database for foxtail millet; (B) research on the contribution of structural variants to domestication and improvement; (C) gene mapping of agricultural traits; and (D) acceleration of the breeding process. This figure was adapted from He et al. (2023).

Ushering in the pan-genomic era for foxtail millet

In the past two decades, crop genomics has enabled the exploration of domestication history, functional gene discovery, and molecular breeding. The latter has transformed the traditional breeding approach into a more efficient, genome-guided, targeted design process. For example, pan-genomes have promoted functional genomics and molecular breeding of rice, a model crop and representative C3 crop (Shang et al., 2022). By contrast, although abundant and diverse germplasm resources are available for foxtail millet, their exploitation and utilization have been relatively poor, and construction of a genetic resource database for core foxtail millet germplasms is particularly critical. He and collaborators produced de novo, reference-level genome assemblies of 110 core-set accessions, including 35 wild, 40 landrace, and 35 modern cultivated accessions, chosen from 1844 Setaria accessions of different subgroups, regions, and ecotypes, representing the broadest range of diversity in S. italica and S. viridis (He et al., 2023). The core-set accessions included those that have contributed significantly to foxtail millet breeding and/or research, such as breeding backbone parent lines (Liushiri and ai88) and accessions with high eating and cooking quality (Jingu21 and Huangjinmiao), strong drought tolerance (Zhonggu 2), wide climate adaptation (Yugu 18), and easy transformation for gene functional analysis (Ci846). These accessions also encompass a diversity of plant architecture, panicle shape and yield, thousand-grain weight, grain length and width, stem diameter, tiller number, and heading time. More importantly, these accessions cover over 85% of the SNP variations among the 1844 Setaria accessions. They represent a pan-genome comprising 73 528 gene families, including 23.8% core genes, 42.9% soft core genes, 29.4% dispensable genes, and 3.9% private genes. About 10 000 structural variants (SVs) were identified per Setaria genome, numbers comparable to those in tomato (Li et al., 2023) but lower than those in rice (Shang et al., 2022). A graph-based reference genome of Setaria was constructed by integrating 107 151 insertions, 76 915 deletions, and 363 inversions across 112 S. italica and S. viridis accessions into the Yugu1 reference genome. The constructed figure contains alternate segments beyond those present in the reference sequence, facilitating the mapping of short reads from sequences that are absent or highly diverged in the reference genome. This foxtail millet pan-genome offers insights into genomic variations across wild and cultivated Setaria, providing valuable resources for functional genomic analyses and precision breeding of foxtail millet. The availability of a graph-based genome sequence, which surpasses conventional single-genome reference assemblies, has the potential to capture additional missing heritability. It can also facilitate comparative genomic research and functional gene mining in Gramineae.

Application of the pan-genome to foxtail millet breeding

Pan-genome variation provides insights for crop domestication and improvement

Cultivated foxtail millet has always been classified into two distinct subgroups that exhibit a close correlation with their respective geographic and climatic distributions, as well as farming traditions. The larger global dataset allowed He et al. (2023) to further divide foxtail millet cultivars into three subpopulations: subgroups C1 and C2 were consistent with types 1 and 2 in a previous study (Jia et al., 2013), and the new subgroup C3 was broadly distributed all over the world, suggesting that it may be more adaptable to a broader range of ecological environments than the other two subgroups. Identification of functional genes in genetically differentiated subpopulations, such as the wild species and C3, holds the potential to uncover lineage-specific elite genes that can be introduced into other subpopulations for foxtail millet improvement. In addition, on the basis of phylogenetic and population structure analyses, He and colleagues confirmed the single origin of foxtail millet in China (He et al., 2023). Using high-quality variation maps constructed from microcore germplasms, they identified 4734 SVs related to domestication and breeding improvement. A total of 680 genes that were continuously selected during domestication and improvement were identified and were mainly enriched in biological processes such as reproductive process, photoperiod, pigment accumulation, and nitrogen utilization. These genes and SVs are an important breakthrough for subsequent interpretation of the domestication traits and unique broad adaptability of Setaria. He et al. also demonstrated the utility of these SVs for dissecting the genetic basis of domestication and improvement. Comparative genome analysis, genetic mapping, and gene functional verification targeted two key genes, Sh1 (for seed shattering) and SiGW3 (for grain weight and size), that were identified as being related to domestication. Exciting as these insights are, many other genes are waiting to be discovered through more comprehensive assessments of the foxtail millet pan-genome. This will be important, as minor crops are rich in diversity, and the extent of their domestication is generally lower than that of major crops, so genetic variations that have been lost in main crops may be retained in the foxtail millet genome. Exploration of gene resources for minor crops can therefore promote their breeding, and related, excellent germplasm resources may provide great opportunities for improvement of major crops.

A graph-based genome is important for gene mapping and precision breeding

Now more than ever, the challenges associated with feeding an ever-expanding population under increasingly variable climate conditions underscore the need for crop improvement. At present, accurate identification and evaluation of the phenotypes and genotypes of foxtail millet germplasm resources are still in their infancy, and substantial genetic resources remain unexplored. This restricts the pace of efforts to improve foxtail millet germplasm in order to help solve critical problems in crop production. For example, Jingu21, one of the most popular cultivars of high-quality foxtail millet, which was developed as long ago as 1973 and obtained national registration in 1991, is highly susceptible to downy mildew. Pan-genomic data could now be used to solve key problems such as the susceptibility of Jingu21 to downy mildew.

Most genotype–phenotype association studies have focused on SNPs and insertions or deletions, meaning that SVs are overlooked. This has limited capture of the entire landscape of genetic variation and identification of causal variations in quantitative trait locus and GWAS analyses. SVs have been associated with important yield components and quality-related traits in crops such as soybean (Liu et al., 2020) and tomato (Li et al., 2023). Likewise, pan-genomic studies in rice (Shang et al., 2022) and pearl millet (Yan et al., 2023) have shown how SVs have directly shaped environmental adaptations and agronomic traits. Pan-genome variations in foxtail millet enabled He and colleagues to map key genes and make more accurate phenotype predictions. With 226 sets of high-quality phenotype data accumulated over 11 years, He et al. (2023) identified 1084 signals that were significantly associated with phenotypes using SNP- and SV-GWASs and demonstrated that the introduction of SVs could significantly improve the accuracy of phenotype prediction. Using data from 680 foxtail millet accessions, they performed GWASs and genomic selection (GS) on 68 traits across 13 different geographic locations, each with distinct climatic conditions. Approximately 1000 high-effect genetic markers (SNPs/SVs) were identified for each group of phenotypes; 97% of the phenotypes were predicted with a precision greater than 0.7; and an optimal graph-based pan-genome GS breeding method was established for foxtail millet. The potential breeding values of yield- and grain-quality-related traits were also evaluated. These markers have great significance for minor crops such as foxtail millet for which there has been little large-scale functional genome research. In the short term, breeders can directly use these resources to accelerate crop improvement under different climatic conditions. In general, more than 200 accessions are required for GWAS; however, the study by He et al. shows that as long as the population guarantees sufficient genetic diversity, even 110 accessions are sufficient for highly accurate GWAS analysis. This study showed that pan-genomic variation can play a crucial role in guiding and accelerating crop improvement through molecular-marker-assisted breeding, GS, and genome editing. The time for smart breeding is coming (Xu et al., 2022), and the work of He et al. (2023) has laid a foundation for closing the gap between foxtail millet and major crops and should play a vital role in reinvigorating this ancient crop.

Plant genomics is moving into an era of family-wide, super graph-based pan-genomes

Understanding the evolution of foxtail millet will require dissecting the full spectrum of genetic variations that underlie the domestication and extensive climate adaptations of Setaria, as well as the role of genome diversity. A super pan-genome enables the study of gene function and evolution across different species or populations by unifying their genome characteristics. Understanding how domestication events have shaped the existing genomes of different species will promote the development of robust strategies for genetic improvement of future crops and protection of germplasm resources (Wang et al., 2023). A graph-based genome can store and display genetic variation information for multiple individuals in a species, making this information easily accessible. Insertion or deletion of large fragments, differences in copy number, and other types of variation cannot be effectively identified with linear genomes, but the emergence of graph-based genomes solves this problem. The graph-based genome is significantly better than classical linear reference assemblies for calling all types of variants, not only SVs but also SNPs and insertions or deletions, thus providing a greater impetus for research on crop improvement, gene breeding, species evolution, and other topics. This is particularly important for crop species because crop improvement depends, to a great extent, on understanding the genetic diversity within gene pools and its effect on agronomic traits. Graph-based genomes will also facilitate functional genomics by enabling the accurate detection of sequence variation and provide excellent resources for the study of genome evolution.

Assemblies of small haploid prokaryotic pan-genomes have crossed species and even phylum boundaries. As pan-genomes continue to be assembled for different plant species, research is expanding beyond the species level, and we can begin to connect pan-genomes to the genus or even family level. This is the case with crops like Setaria (He et al., 2023), allowing us to ask questions such as what gene content is needed to make the Poaceae or Brassicaceae family. Ultimately, an extensive pan-genome of the whole plant field could be constructed, enabling us to understand common and specific domestication patterns and thus promoting the improvement of current crops and the creation of new crops by de novo domestication to meet the demands of an increasing population and changing climate.

There are still challenges to making full use of these vast genomic resources. Although graph-based genomes can already store multiple SVs, they cannot yet integrate relatively complex SVs, such as inverted duplications and translocations. First, more effective tools and algorithms must be developed to completely integrate all types of genetic variation into one graph-based genome. Second, most currently available bioinformatics tools are applicable only to linear reference genomes; all upstream and downstream analysis of graph-based pan-genomes requires the development of enhanced tools for SV detection. We anticipate that development of a suitable graph-based genome analysis pipeline will fully leverage the potential of such genomes, and we envision that utilization of graph-based pan-genomes will propel crop genomics to unprecedented heights.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20216).

Author contributions

Writing – original draft, Y.L.; writing – review & editing, Y.H.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professors Donald Grierson and Rupert Fray (University of Nottingham) and Professor Luis Mur (Aberystwyth University) for their comments and suggestions on the manuscript. No conflict of interest is declared.

Published: October 20, 2023

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Contributor Information

Yinpei Liang, Email: lyp@sxau.edu.cn.

Yuanhuai Han, Email: hanyuanhuai@sxau.edu.cn.

References

- Bennetzen J.L., Schmutz J., Wang H., Percifield R., Hawkins J., Pontaroli A.C., Estep M., Feng L., Vaughn J.N., Grimwood J., et al. Reference genome sequence of the model plant Setaria. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:555–561. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Liu X., Quan Z., Cheng S., Xu X., Pan S., Xie M., Zeng P., Yue Z., Wang W., et al. Genome sequence of foxtail millet (Setaria italica) provides insights into grass evolution and biofuel potential. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:549–554. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G., Huang X., Zhi H., Zhao Y., Zhao Q., Li W., Chai Y., Yang L., Liu K., Lu H., et al. A haplotype map of genomic variations and genome-wide association studies of agronomic traits in foxtail millet (Setaria italica) Nat. Genet. 2013;45:957–961. doi: 10.1038/ng.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Zhang H., Li X., Shen H., Gao J., Hou S., Zhang B., Mayes S., Bennett M., Ma J., et al. A mini foxtail millet with an Arabidopsis-like life cycle as a C4 model system. Nat. Plants. 2020;6:1167–1178. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0747-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamidi S., Healey A., Huang P., Grimwood J., Jenkins J., Barry K., Sreedasyam A., Shu S., Lovell J.T., Feldman M., et al. A genome resource for green millet Setaria viridis enables discovery of agronomically valuable loci. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:1203–1210. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0681-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Gao J., Song J., Guo K., Hou S., Wang X., He Q., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Yang Y., et al. Multi-omics analyses of 398 foxtail millet accessions reveal genomic regions associated with domestication, metabolite traits, and anti-inflammatory effects. Mol. Plant. 2022;15:1367–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q., Tang S., Zhi H., Chen J., Zhang J., Liang H., Alam O., Li H., Zhang H., Xing L., et al. A graph-based genome and pan-genome variation of the model plant Setaria. Nat. Genet. 2023;55:1232–1242. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01423-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang L., Li X., He H., Yuan Q., Song Y., Wei Z., Lin H., Hu M., Zhao F., Zhang C., et al. A super pan-genomic landscape of rice. Cell Res. 2022;32:878–896. doi: 10.1038/s41422-022-00685-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., He Q., Wang J., Wang B., Zhao J., Huang S., Yang T., Tang Y., Yang S., Aisimutuola P., et al. Super-pangenome analyses highlight genomic diversity and structural variation across wild and cultivated tomato species. Nat. Genet. 2023;55:852–860. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01340-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Du H., Li P., Shen Y., Peng H., Liu S., Zhou G.A., Zhang H., Liu Z., Shi M., et al. Pan-genome of wild and cultivated soybeans. Cell. 2020;182:162–176.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H., Sun M., Zhang Z., Jin Y., Zhang A., Lin C., Wu B., He M., Xu B., Wang J., et al. Pangenomic analysis identifies structural variation associated with heat tolerance in pearl millet. Nat. Genet. 2023;55:507–518. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01302-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Zhang X., Li H., Zheng H., Zhang J., Olsen M.S., Varshney R.K., Prasanna B.M., Qian Q. Smart breeding driven by big data, artificial intelligence, and integrated genomic-enviromic prediction. Mol. Plant. 2022;15:1664–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Huang S., Yang Z., Lai J., Gao X., Shi J. A high-quality, phased genome assembly of broomcorn millet reveals the features of its subgenome evolution and 3D chromatin organization. Plant Commun. 2023;4 doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]