Abstract

Background:

Alcohol use disorder is a public health problem, especially among US veterans. This study examined the nature and predictors of 10-year trajectories of alcohol consumption in US veterans.

Methods:

Data were analyzed from the 2011–2021 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study, a nationally representative, longitudinal study of 2309 US veterans.

Results:

Latent growth mixture modeling analyses revealed four trajectories of alcohol consumption (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption [AUDIT-C]) over a 10-year period: excessive (4.1%; mean [standard deviation] AUDIT-C baseline=8.6 [2.0], slope= −0.33 [0.07]); at-risk (22.1%; baseline=4.1 [1.6], slope=0.02 [0.07]); rare (71.7%; baseline=1.2 [1.3], slope= −0.01 [0.03]); and recovering alcohol consumption (2.1%; baseline=8.4 [1.9], slope= −0.70 [0.14]). The strongest predictors of excessive vs. rare alcohol consumption group were younger age (relative variance explained [RVE]=27.8%), and lower agreeableness (RVE=27.0%); at-risk vs. rare alcohol consumption group were fewer medical comorbidities (RVE=82.3%); recovering vs. rare alcohol consumption group were greater dysphoric arousal symptoms (RVE=46.1%) and current mental health treatment (RVE=26.5%); excessive vs. at-risk alcohol consumption group were younger age (RVE=25.9%), greater dysphoric arousal symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (RVE=22.0%), and lower conscientiousness (RVE=19.1%); and excessive vs. recovering alcohol consumption group were current mental health treatment (RVE=61.1%) and secure attachment style (RVE=12.4%).

Conclusions

Over the past decade, more than 1 in 4 US veterans consumed alcohol at the at-risk-to-excessive level. Veterans who are younger, score lower on agreeableness and conscientiousness, endorse greater dysphoric arousal symptoms, and currently not engaged in mental health treatment may require close monitoring and prevention efforts to mitigate the risk of a chronic course of at-risk-to-excessive alcohol consumption.

1. Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a significant public health concern that accounts for three million deaths worldwide every year (World Health Organization, 2022). The prevalence of AUD is higher among US veterans than non-veterans (Williamson et al., 2018). For example, in a nationally representative study of US veterans, the lifetime and past-year prevalence of AUD were 42.2% and 14.8%, respectively (Fuehrlein et al., 2016), whereas in the general US adult population it was 29.1% and 13.9%, respectively (Grant et al., 2015). Further, in a recent cross-sectional survey of 1730 US veterans, 24.1% screened positive for hazardous alcohol consumption group (Adams et al., 2022). Further, in a study on 189 Israel Defense Forces male combat veterans, the prevalence of risky or hazardous or above level alcohol consumption group was 11.3% (Feingold and Zerach, 2021).

While there has been an abundance of research on the epidemiology of alcohol use, most studies have focused on AUD and have been cross-sectional; longitudinal studies of alcohol use are scarce. The lack of longitudinal data is particularly evident in studies of military veterans. To date, only three known studies have examined alcohol use trajectories in this population. Two studies were on approximately 300 Vietnam-era veterans (Jacob et al., 2010, 2005); the other study was our previous longitudinal study that examined the 4-year trajectories of alcohol consumption in a nationally representative sample of veterans (Fuehrlein et al., 2018). In that study, we found that lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD) was a strong determinant for the excessive alcohol consumption group, whereas lower social support and fewer medical conditions were strong determinants for the at-risk alcohol consumption group (Fuehrlein et al., 2018). Further, we found that secure attachment style, greater social support and no history of MDD were strong determinants for the recovering vs. the excessive alcohol consumption group. Characterization of the nature and predictors of courses of alcohol consumption in longitudinal studies is important, as it provides population-based insight into characteristics of individuals who may be at heightened risk for persistent alcohol use, which can help inform prevention and early intervention efforts.

Toward this end, we sought to build upon our previous 4-year findings (Fuehrlein et al., 2018) and examine the nature and the risk and protective factors associated with 10-year alcohol consumption trajectories in a nationally representative sample of US veterans. We had two aims: (1) to identify common trajectories of alcohol consumption; and (2) to identify risk and protective factors associated with distinct trajectories of alcohol consumption. Based on our previous studies (Fuehrlein et al., 2018; Palmisano et al., 2022), we hypothesized that psychiatric conditions such as MDD and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) would be strong determinants for the excessive alcohol consumption group, and that greater social support and secure attachment style would be strong determinants for the recovering trajectory.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Data were analyzed from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study (NHRVS), which surveyed a nationally representative prospective sample of US military veterans from 2011 to 2021. The NHRVS sample was drawn from KnowledgePanel, a research panel of more than 50,000 households that is maintained by Ipsos, a survey research firm. KnowledgePanel® is a probability-based, online non-volunteer access survey panel of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults that covers approximately 98% of U.S. households. Panel members are recruited through national random samples, originally by telephone and now almost entirely by postal mail. Households are provided with access to the Internet and computer hardware if needed. KnowledgePanel® recruitment uses dual sampling frames that include both listed and unlisted telephone numbers, telephone and non-telephone households, and cell-phone-only households, as well as households with and without Internet access. Details of the study design have been described previously (Fuehrlein et al., 2018).

Demographic data of survey panel members are assessed regularly by Ipsos using the same set of questions used by the U.S. Census Bureau. To permit generalizability of study results to the entire population of U.S. veterans, the Ipsos statistical team computed post-stratification weights using the following benchmark distributions of U.S. military veterans from the 2011 Current Veteran Population Supplemental Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey: age, sex, race/ethnicity, Census Region, metropolitan status, education, household income, branch of service, and years in service. An iterative proportional fitting (raking) procedure was used to produce the final post-stratification weights. All participants provided informed consent and the study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System.

Of the 3157 veterans who completed an initial survey in 2011, 2309 (73.1%) completed at least one or more follow-up assessments (mean number of follow-ups: 2.6, SD=1.2) and were the focus of this study. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, and all participants provided informed consent.

2.2. Assessments

2.2.1. Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C). The AUDIT-C consists of three questions that assess the frequency of alcohol consumption and binging (range: 0–12). Higher scores indicate more severe alcohol consumption. A cut-off score of 4 for men and 3 for women is indicative of hazardous alcohol consumption (VA Health Care, 2013).

Table 1 presents the details of measures used in this study.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and potential risk and protective factors examined in the study.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Age (continuous), sex (dichotomous: male vs female), race (dichotomous: White vs non-White), education (dichotomous: some college or higher vs up to high school diploma), marital status (dichotomous: married/living with partner vs unmarried), income (dichotomous: $60,000 or more vs less than $60,000), years of military service, combat veteran status. |

| Psychiatric/Medical factors | |

| MDD symptom severity | Measured using the two depressive symptoms of the PHQ-4 occurring in the past two weeks; a score ≥ 3 was indicative of a positive screen for MDD (Kroenke et al., 2009) |

| PTSD symptom severity | PTSD – assessed with the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; a score ≥ 33 was indicative of a positive screen for PTSD (Weathers et al., 2013) |

| Cumulative trauma burden | Count of potentially traumatic events on the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (Weathers et al., 2013) |

| Cognitive functioning | Cognitive functioning was assessed by the Medical Outcomes Study Cognitive Functioning Scale (Stewart and Ware, 1991) |

| Number of medical conditions | Sum of number of medical conditions endorsed in response to question: “Has a doctor or healthcare professional ever told you that you have any of the following medical conditions?” (e.g., arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, asthma, kidney disease) Range: 0–24 conditions. |

| Current mental health treatment | Positive endorsement of current treatment with psychotropic medication and/or psychotherapy or counseling: “Are you currently taking prescription medication for a psychiatric or emotional problem?” Are you currently receiving psychotherapy or counseling for a psychiatric or emotional problem? |

| Psychosocial factors | |

| Personality | Assessed using the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) (Gosling et al., 2003), a 10-item self-report brief measure of the “Big Five” personality traits of emotional stability (anxious vs confident and calm), extraversion (outgoing vs reserved), openness to experience (imaginative and inventive vs cautious and routine-like), agreeableness (friendly and cooperative vs detached), and conscientiousness (efficient and organized vs careless) |

| Resilience | Score on Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (Campbell-Sills and Stein, 2007) |

| Dispositional optimism | Score on single-item measure of optimism from Life Orientation Test-Revised (Scheier et al., 1994); “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best” (rating 1 =strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) |

| Purpose in life | Score on Purpose in Life Test-Short Form (Schulenberg et al., 2010) (Schulenberg et al., 2010) |

| Secure attachment style | Choose one: a) I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; b) I find it relatively easy to get close to others (secure); c) I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like (Hazan and Shaver, 1990) |

| Perceived social support | Score on 5-item version of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale (Amstadter et al., 2011; Sherbourne and Stewart, 1991) |

Note. DSM-5 =Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, MDD=major depressive disorder, PHQ=patient health questionnaire, PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder.

2.3. Data analysis

2.3.1. Latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM) analysis

We conducted LGMM using robust full-information maximum likelihood in Mplus (Muthen and Muthen, 2002). LGMM evaluates whether the population under study is composed of a mixture of subpopulations that display distinct trajectories of change over time instead of computing a single mean for the population, as in traditional regression or growth-curve approaches (Muthen, 2004). AUDIT-C scores at each of the five assessments were entered into this analysis. We compared 1–6-class unconditional LGMMs (no covariates) and assessed their relative fit using conventional indices, including the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), entropy, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood test (LRT) (Lo et al., 2001), and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) (McLachlan and Peel, 2000). We identified the best-fitting models based on smaller BIC and AIC values and higher entropy values, and on results of the LRT and the BLRT, which quantify the likelihood that the data can be described by a model with one less trajectory. In addition to inspecting these formal criteria, we also considered class sizes, parsimony, and interpretability of the various solutions and aimed to select generalizable final models (Nylund et al., 2007). Each veteran was assigned the trajectory in which they had the greatest posterior probability. Analyses of variance and chi-square tests were used to conduct bivariate comparisons of alcohol consumption trajectory groups with sociodemographic, military, health, and psychosocial variables. Variables that differed by trajectory group at the p < 0.05 level in bivariate analyses were then incorporated into an LGMM of the best-fitting solution using the ‘R3STEP’ command in Mplus (Asparouhouv and Muthen, 2014). We then conducted post-hoc analyses of multi-component measures (e.g., medical comorbidities) to identify specific indicator variables associated with these trajectories. Lastly, significant variables from multivariable analyses were entered into a relative importance analysis, which computed the explained variance in alcohol consumption patterns that is attributable to each independent variable while accounting for intercorrelations among these variables (Tonidandel and LeBreton, 2010).

3. Results

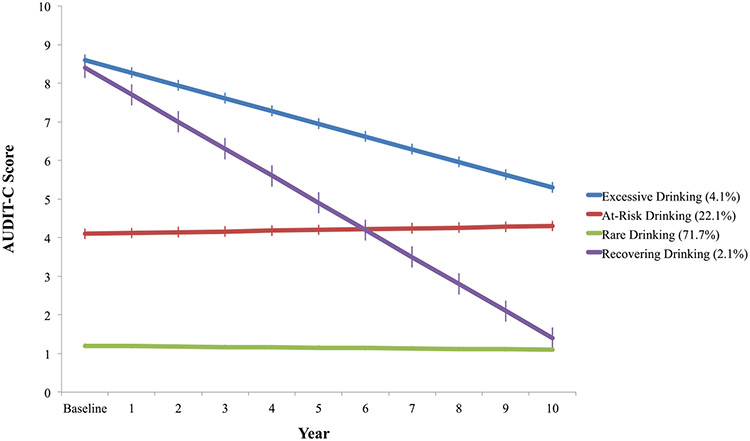

Based on theory, fit statistics (See Table 2), and parsimony, the 4-class model was selected as the best fitting model. As shown in Fig. 1, this model included excessive (N = 74, weighted 4.1%), at-risk (N = 547, weighted 22.1%), rare (N = 1650, weighted 71.7%), and recovering (N = 38, weighted 2.1%) trajectories of alcohol consumption.

Table 2.

Fit statistics of unconditional 1- to 6-class models of 10-year alcohol consumption trajectories.

| Classes | BIC | SSABIC | AIC | Entropy | LMR adjusted LRT p value | Bootstrapped LRT p | N (%) smallest dass | Class Probabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29,845.843 | 29,814.071 | 29,788.397 | – | – | – | 2309 (100%) | 1.00 |

| 2 | 29,333.499 | 29,292.195 | 29,258.819 | 0.939 | 0.0001 | < .0001 | 134 (5.8%) | .911-.989 |

| 3 | 29,097.856 | 29,047.021 | 29,005.942 | 0.847 | 0.2157 | < .0001 | 92 (4.0%) | 0.878–0.950 |

| 4 | 28,909.685 | 28,849.318 | 28,800.538 | 0.874 | 0.0200 | < .0001 | 38 (1.6%) | 0.873–0.949 |

| 5 | 28,766.313 | 28,696.415 | 28,639.933 | 0.886 | 0.5680 | < .0001 | 11 (0.5%) | 0.863–0.949 |

| 6 | 28,816.382 | 28,736.952 | 28,672.767 | 0.878 | 0.5399 | < .0001 | 11 (0.5%) | 0.845–0.970 |

Note. AIC=Akaike Information Criterion; BIC= Bayesian Information Criterion; LMR=Lo-Mendell-Rubin; LRT=Likelihood Ratio Test; SSABIC=Sample Size Adjusted BIC.

Fig. 1.

Mean AUDIT-C scores for each 10-year alcohol consumption trajectory. Note. AUDIT-C=Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption.Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals computed from interpolated intercept and slope estimates.

The excessive alcohol consumption group had a mean baseline AUDIT-C score of 8.6 (SD=2.0) that decreased steadily over the 10-year study period (mean 10-year slope= −0.33, SD=0.07); at-risk alcohol consumption group had a mean baseline AUDIT-C score of 4.1 (SD=1.6) that remained stable (mean slope=0.02, SD=0.07); rare alcohol consumption group had a mean baseline AUDIT-C score of 1.2 (SD=1.3) that remained stable (mean slope= −0.01, SD=0.03); and recovering alcohol consumption group had a mean baseline AUDIT-C score of 8.4 (1.9) that declined markedly over time (mean slope= −0.70, SD=0.14).

3.1. Predictors of symptomatic alcohol consumption trajectories

Table 3 shows sociodemographic, military, health, and psychosocial characteristics of the different alcohol consumption trajectories. Significant group differences were observed for all of the variables except combat veteran status, number of traumas, somatic symptoms, cognitive functioning, extraversion, openness to experiences, and perceived social support.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic, military, health and psychosocial variables by 10-year trajectories of alcohol consumption.

| Rare Drinkers N = 1650 (weighted 71.7%) |

At-Risk Drinkers N = 547 (weighted 22.1%) |

Excessive Drinkers N = 74 (weighted 4.1%) |

Recovering Drinkers N = 38 (weighted 2.1%) |

Test of difference |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted mean (SD) or N (weighted %) |

Weighted mean (SD) or N (weighted %) |

Weighted mean (SD) or N (weighted %) |

Weighted mean (SD) or N (weighted %) |

|||

| Age | 62.2 (14.0) | 61.6 (15.3) | 53.2 (14.1) | 55.7 (19.9) | 13.43 | < .001 |

| Male sex | 1476 (90.3%) | 509 (93.4%) | 74 (100%) | 34 (93.3%) | 13.24 | 0.004 |

| White race/ethnicity | 1372 (77.1%) | 482 (79.4%) | 63 (73.9%) | 30 (60.0%) | 9.45 | 0.024 |

| Some college or higher education | 1397 (67.8%) | 493 (75.7%) | 57 (56.8%) | 29 (42.2%) | 31.65 | < .001 |

| Household income $60 K or higher | 830 (43.7%) | 347 (56.2%) | 42 (40.9%) | 18 (33.3%) | 27.00 | < .001 |

| Married/partnered | 1321 (75.9%) | 436 (74.6%) | 54 (68.2%) | 24 (57.8%) | 9.99 | 0.019 |

| Combat veteran | 555 (31.7%) | 194 (35.0%) | 33 (35.2%) | 18 (42.2%) | 3.93 | 0.27 |

| Years of military service | 6.8 (7.2) | 8.1 (8.9) | 4.7 (4.8) | 4.8 (4.4) | 7.89 | < .001 |

| Number of traumas | 4.6 (3.8) | 4.5 (3.8) | 4.6 (4.1) | 4.8 (4.5) | 0.17 | 0.92 |

| MDD symptom severity | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.7 (1.3) | 1.0 (1.4) | 3.89 | 0.009 |

| PTSD symptom severity | 22.9 (9.6) | 21.7 (7.5) | 26.3 (12.9) | 26.9 (12.4) | 7.81 | < .001 |

| Intrusions | 6.2 (2.8) | 5.8 (2.0) | 6.7 (3.8) | 6.7 (3.7) | 4.37 | 0.005 |

| Avoidance | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.8) | 3.1 (1.9) | 3.39 | 0.017 |

| Emotional numbing | 6.8 (3.3) | 6.5 (2.7) | 7.8 (4.2) | 8.4 (4.2) | 6.93 | < .001 |

| Dysphoric arousal | 4.6 (2.2) | 4.4 (1.9) | 5.5 (2.7) | 5.6 (2.7) | 8.31 | < .001 |

| Anxious arousal | 2.8 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.3) | 3.4 (2.1) | 3.2 (1.5) | 6.99 | < .001 |

| Number of medical conditions | 2.7 (2.0) | 2.2 (1.6) | 2.1 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.6) | 12.25 | < .001 |

| Somatic symptoms | 2.5 (3.9) | 2.0 (3.2) | 2.4 (3.1) | 2.5 (4.3) | 2.18 | 0.089 |

| Cognitive functioning | 90.0 (15.5) | 91.7 (11.6) | 90.7 (17.8) | 90.3 (14.7) | 1.77 | 0.15 |

| Extraversion | 4.0 (1.4) | 4.0 (1.4) | 4.0 (1.8) | 4.0 (1.2) | 0.18 | 0.91 |

| Agreeableness | 5.2 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.1) | 4.6 (1.4) | 4.6 (1.1) | 8.19 | < .001 |

| Conscientiousness | 5.8 (1.1) | 5.9 (1.1) | 5.4 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.4) | 5.55 | < .001 |

| Emotional stability | 5.3 (1.3) | 5.4 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.5) | 5.0 (1.3) | 5.91 | < .001 |

| Openness to experiences | 4.9 (1.2) | 5.0 (1.2) | 4.9 (1.1) | 4.6 (0.9) | 1.71 | 0.16 |

| Resilience | 29.3 (7.1) | 30.3 (6.7) | 29.4 (7.4) | 28.0 (9.2) | 3.13 | 0.025 |

| Dispositional optimism | 4.8 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.4) | 4.5 (1.6) | 4.4 (1.4) | 3.25 | 0.021 |

| Purpose in life | 21.4 (4.6) | 21.9 (4.3) | 20.4 (4.1) | 19.5 (4.9) | 5.81 | < .001 |

| Secure attachment style | 1221 (72.4%) | 408 (72.1%) | 40 (61.4%) | 23 (51.1%) | 14.28 | 0.003 |

| Perceived social support | 19.4 (5.1) | 19.4 (5.0) | 19.1 (5.6) | 19.6 (3.7) | 0.15 | 0.93 |

| Current mental health treatment | 332 (21.4%) | 104 (14.6%) | 13 (21.6%) | 13 (37.8%) | 19.03 | < .001 |

Note. MDD=major depressive disorder; PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder; SD=standard deviation.

Table 4 shows results of multivariable analyses of variables associated with the alcohol consumption trajectories. Relative to the rare alcohol consumption group, the strongest predictors of the excessive alcohol consumption group were younger age (27.8% relative variance explained [RVE]), lower agreeableness (27.0% RVE), fewer years in the military (13.1% RVE), and lower conscientiousness (12.6%) and higher dysphoric arousal symptoms (10.0%).

Table 4.

Results of multivariable analysis of sociodemographic, military, health and psychosocial variables associated with symptomatic 10-year trajectories of alcohol consumption.

| At-risk vs. Rare |

Excessive vs. Rare |

Recovering vs. Rare |

Excessive vs. At-risk |

Excessive vs. Recovering |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR (95%CI) | RRR (95%CI) | RRR (95%CI) | RRR (95%CI) | RRR (95%CI) | |

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.95 (0.93–0.97)*** | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.95 (0.93–0.98)*** | 0.92 (0.87–0.98)* |

| Male sex | 1.32 (0.84–2.04) | – | 2.44 (0.64–9.09) | – | – |

| White race/ethnicity | 1.20 (0.90–1.61) | 1.22 (0.65–2.27 | 0.34 (0.16–0.70)** | 1.20 (0.59–2.47) | 7.28 (1.89–27.95)** |

| Some college or higher education | 1.27 (0.97–1.66) | 0.49 (0.29–0.83)** | 0.30 (0.14–0.63)** | 0.36 (0.19–0.67)** | 2.61 (0.79–8.58) |

| Household income $60 K or higher | 1.50 (1.18–1.91)*** | 0.90 (0.54–1.51) | 0.94 (0.44–1.97) | 0.64 (0.35–1.16) | 0.39 (0.10–1.51) |

| Married/partnered | 0.90 (0.68–1.19) | 0.51 (0.29–0.91)* | 0.61 (0.27–1.40) | 0.78 (0.39–1.58) | 0.72 (0.18–2.89) |

| Years of military service | 1.02 (1.01–1.03)* | 0.93 (0.88–0.98)** | 0.97 (0.92–1.04) | 0.93 (0.87–0.98)* | 0.88 (0.79–0.99)* |

| MDD symptom severity | 1.06 (0.92–1.21) | 1.06 (0.83–1.36) | 0.88 (0.60–1.30) | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) | 1.07 (0.57–2.04) |

| Intrusions | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 0.87 (0.75–1.01) | 0.81 (0.63–1.04) | 1.03 (0.84–1.27) | 0.91 (0.64–1.29) |

| Avoidance | 1.04 (0.91–1.18) | 0.83 (0.64–1.09) | 0.96 (0.65–1.42) | 0.76 (0.52–1.10) | 0.69 (0.36–1.34) |

| Emotional numbing | 0.93 (0.87–0.99)* | 1.03 (0.90–1.17) | 1.03 (0.85–1.25) | 1.12 (0.95–1.31) | 1.18 (0.84–1.66) |

| Dysphoric arousal | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) | 1.26 (1.07–1.48)** | 1.26 (1.01–1.58)* | 1.24 (1.03–1.49)* | 1.07 (0.73–1.57) |

| Anxious arousal | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) | 1.02 (0.83–1.25) | 0.87 (0.64–1.18) | 0.85 (0.68–1.06) | 1.35 (0.77–2.39) |

| Number of medical conditions | 0.85 (0.79–0.91)*** | 0.95 (0.82–1.10) | 0.90 (0.73–1.11) | 1.17 (0.96–1.43) | 1.17 (0.77–1.78) |

| Agreeableness | 0.95 (0.85–1.07) | 0.76 (0.60–0.96)* | 0.74 (0.54–1.01) | 0.80 (0.59–1.07) | 0.48 (0.24–0.98)* |

| Conscientiousness | 1.00 (0.89–1.13) | 0.68 (0.54–0.85)*** | 0.94 (0.66–1.33) | 0.66 (0.50–0.86)** | 0.68 (0.42–1.10) |

| Emotional stability | 1.03 (0.92–1.17) | 1.08 (0.83–1.40) | 1.02 (0.70–1.49) | 0.98 (0.73–1.31) | 1.17 (0.72–1.92) |

| Resilience | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 0.86 (0.82–0.91) | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) |

| Optimism | 1.00 (0.90–1.10) | 1.00 (0.83–1.22) | 0.93 (0.69–1.25) | 1.04 (0.83–1.30) | 1.17 (0.72–1.92) |

| Purpose in life | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) | 1.32 (1.08–1.61)** |

| Secure attachment style | 0.75 (0.56–0.99)* | 0.95 (0.54–1.70) | 0.63 (0.29–1.38) | 1.53 (0.78–3.00) | 3.66 (1.06–12.61)* |

| Current mental health treatment | 0.76 (0.53–1.04) | 0.85 (0.44–1.61) | 2.37 (1.03–5.46)* | 1.56 (0.77–3.17) | 0.18 (0.04–0.77)* |

Note. MDD=major depressive disorder; RRR=relative risk ratio; 95%CI= 95% confidence interval.

Significant association:

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Relative to the rare alcohol consumption group, the strongest predictors of the at-risk alcohol consumption group were fewer medical comorbidities (RVE=82.3%); specifically, not having rheumatoid arthritis (27.1% relative variance explained [RVE]), sleep disorder (11.7% RVE), and migraine headaches (11.7% RVE). Higher household income (15.0% RVE) was another strong predictor of the at-risk alcohol consumption group.

Relative to the rare alcohol consumption group, the strongest predictors of the recovering alcohol consumption group were greater dysphoric arousal symptoms of PTSD (46.1% RVE), current mental health treatment (26.5% RVE), and lower education (24.6% RVE).

Relative to the at-risk alcohol consumption group, the strongest predictors of the excessive alcohol consumption group were younger age (25.9% RVE), greater dysphoric arousal symptoms of PTSD (22.0% RVE), lower conscientiousness (19.1% RVE), fewer years in the military (16.6% RVE), and lower education (16.4% RVE).

Relative to the recovering alcohol consumption group, the strongest predictors of the excessive alcohol consumption group were current mental health treatment (61.1% RVE), secure attachment style (12.4% RVE), and non-Hispanic White race/ethnicity (12.1% RVE).

4. Discussion

This study examined the nature and predictors of 10-year trajectories of alcohol consumption in a nationally representative sample of US military veterans. Four trajectories of alcohol consumption—classified as excessive, at-risk, recovering, and rare—were identified, with more than 1 in 4 veterans consuming alcohol at the at-risk-to-excessive levels over the 10-year study period. Relative to the rare alcohol consumption group, the strongest predictors of the excessive alcohol consumption group were younger age, and lower agreeableness; the at-risk alcohol consumption group was medical comorbidities; and the recovering alcohol consumption group were greater dysphoric arousal symptoms and current mental health treatment. Further, when differentiating the excessive from at-risk alcohol consumption group, the strongest predictors of the excessive alcohol consumption group were younger age, greater dysphoric arousal symptoms of PTSD, and lower conscientiousness. The strongest predictors of the excessive relative to the recovering alcohol consumption group were current mental health treatment and secure attachment style.

In our study, the excessive alcohol consumption group comprised 4.1% (weighted) of the total sample. This prevalence is substantially lower than our previous study that reported a 14.8% prevalence of AUD (Fuehrlein et al., 2016). However, it should also be noted that the mean AUDIT-C of the at-risk alcohol consumption group (weighted 22.1%) was well above the recommended cut-off score of hazardous alcohol consumption group (VA Health Care, 2013). Thus, it is possible that a substantial proportion of the at-risk alcohol consumption group may in fact meet screening criteria for probable AUD. Collectively, these results underscore the public health significance of chronic at-risk-to-excessive levels of alcohol consumption in the US veteran population, and the importance of timely assessment and early intervention to help mitigate risk for the many adverse health effects of chronic alcohol use in this population.

Alcohol consumption of the excessive trajectory trended downward, declining an average of 3.3 points on the AUDIT-C over the 10-year study period. Given that the sample was in their early 60 s on average at the baseline assessment, this may be in part due to a decline in alcohol consumption with older age. Another plausible explanation is the ‘healthy user bias,’ with veterans who were healthier being more likely to complete follow-up surveys (Shrank et al., 2011). Notably, on average, the at-risk alcohol consumption group had mean AUDIT-C scores at the recommended cut-off for probable AUD, with a subtle increase across the study period (average of 0.7 points), suggesting that this group, which generalizes to more than 1 in 5 veterans, may warrant continued monitoring and possible treatment for AUD. Many of the predictors of the at-risk and the excessive alcohol consumption group have been associated with AUD in prior studies, such as younger age, lower education, and lower income (Grant et al., 2015).

The strongest determinant that differentiated the at-risk from rare alcohol consumption group was having fewer medical conditions (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, migraine headaches). This finding aligns with a recent meta-analysis of 22 studies that examined the association between alcohol consumption and healthy aging, which concluded that light-to-moderate alcohol consumption (e.g., 1–40 g/day, 1–14 drinks/week), relative to no alcohol consumption, is associated with healthy aging (e.g., fewer medical conditions, better survival, and physical performance; (Daskalopoulou et al., 2018). It should also be noted that veterans who had fewer medical conditions at baseline may have been more comfortable consuming more alcohol due to better physical health.

With regard to protective factors, it is encouraging that the one of the strongest predictors of the recovering alcohol consumption group, which evidenced an average 7-point decrease in AUDIT-C scores over the 10-year period, was current mental health treatment. More specifically, current mental health treatment was the strongest predictor of the excessive relative to the recovering alcohol consumption group, explaining more than 60% of the variance. Low agreeableness and conscientiousness were also strong predictors of the excessive relative to the rare and at-risk alcohol consumption groups, respectively. This finding builds upon previous literature showing strong negative correlations between both conscientiousness and agreeableness with alcohol consumption (Lui et al., 2022). Of note, secure attachment style, which was associated with the recovering alcohol consumption group in our previous study (Fuehrlein et al., 2018), was a strong predictor of the excessive relative to the recovering alcohol consumption group in our current study. This finding differs from prior studies, which have found that insecure attachment style was linked to heavy alcohol consumption in adolescents and adults (Vungkhanching et al., 2004). This finding may be explained in part by the greater severity of alcohol consumption in the recovering alcohol consumption group at the baseline assessment.

The role of PTSD in AUD has been an area of interest, primarily due to the high co-occurrence of the two disorders (Seal et al., 2011). In our study, dysphoric arousal, a core symptom cluster of PTSD characterized by anger/irritability and sleep and concentration difficulties, was one of the strongest predictors of the excessive alcohol consumption group (vs. the at-risk alcohol consumption group) and the recovering alcohol consumption group (vs. the rare alcohol consumption group). These findings align with our previous study of an independent, nationally representative sample of US veterans, in which we found that dysphoric arousal symptoms were associated with AUD, and that avoidant coping strategies may mediate this association (Palmisano et al., 2022). Taken together, these findings suggest that the development and maintenance of excessive alcohol consumption group, as well as recovery may be driven in part by avoidance of and/or escape from PTSD symptoms (i.e., ‘self-medicating ‘).

This study has three notable limitations. First, due to the survey design of this study, we used screening instruments to assess psychiatric measures instead of structured clinical interviews. Second, while nationally representative, our sample was comprised predominantly of older White male veterans, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Third, this study was not designed initially to look into outcomes related to alcohol use.

Notwithstanding such limitations, results of this study provide a population-based characterization of predominant trajectories of alcohol consumption in a 10-year, nationally representative longitudinal study of US veterans. Collectively, our findings indicate that veterans who are younger, lower on agreeableness and conscientiousness, endorse greater dysphoric arousal symptoms of PTSD and currently not in mental health treatment may be more likely to have an at-risk-to-excessive alcohol consumption group pattern. Veterans with such characteristics may deserve close clinical attention and monitoring, as well as early interventions and supportive resources. The role of dysphoric arousal symptoms of PTSD, and personality factors may need to be emphasized more in clinical settings when assessing risk for chronic excessive alcohol consumption in veterans. Our finding that current mental health treatment as a strong determinant for the recovering alcohol consumption group underscores the importance of treatment in recovery from excessive alcohol consumption group. Further research is needed to identify more proximate and evolving risk and protective factors for different alcohol consumption group patterns; and evaluate the efficacy of prevention and treatment efforts targeting factors that are found to be mitigating excessive alcohol consumption and promoting recovery from alcohol consumption group in veterans and other high-risk populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the veterans who participated in our study.

Primary funding

This study is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs via 1IK2CX002095-01A1 (J.L.M.O.) and 1IK1CX002532-01 (P.J.N.).

Role of the funder/sponsor

The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Peter J. Na assisted with the study conceptualization, and writing of the paper. Janitza Montalvo-Ortiz collaborated in designing the study, and writing and editing of the manuscript. Ismene L. Petrakis, John H. Krystal, Renato Polimanti, and Joel Gelernter collaborated in the writing and editing of the manuscript. Robert H. Pietrzak designed the study, analyzed the data, and collaborated in the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

Drs. Na, Montalvo-Ortiz, and Pietrzak report no competing interests. Dr. Petrakis has served as a consultant for Alkermes and BioXcel Therapeutics and a grant funded by BioXcel Therapeutics. Dr. Krystal is a scientific advisor to Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, BioXcel Therapeutics, Inc., Cadent Therapeutics (Clinical Advisory Board), PsychoGenics, Inc., Stanley Center for Psychiatric research at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Lohocla Research Corporation. J.K. owns stock and/or stock options in Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Sage Pharmaceuticals, Spring Care, Inc., BlackThorn Therapeutics, Inc., Terran Biosciences, Inc. J.K. reports income < $10 000 per year from: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Biogen, Idec, MA, Biomedisyn Corporation, Bionomics, Limited (Australia), Boehringer Ingelheim International, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Epiodyne, Inc., Heptares Therapeutics, Limited (UK), Janssen Research & Development, L.E.K. Consulting, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc., Perception Neuroscience Holdings, Inc. Spring Care, Inc., Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Takeda Industries, Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. J.K. reports income > $10 000 per year from Biological Psychiatry (Editor). J.K. received the drug, Saracatinib from AstraZeneca and Mavoglurant from Novartis for research related to NIAAA grant “Center for Translational Neuroscience of Alcoholism [CTNA-4] from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals. JK holds the following patents: 1) Seibyl JP, Krystal JH, Charney DS. Dopamine and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors in treatment of schizophrenia. US Patent #:5447948. September 5, 1995; 2) Vladimir, Coric, Krystal, John H, Sanacora, Gerard – Glutamate Modulating Agents in the Treatment of Mental Disorders US Patent No. 8778979 B2 Patent Issue Date: July 15, 2014. US Patent Application No. 15/695164: Filing Date: 09/05/2017; 3) Charney D, Krystal JH, Manji H, Matthew S, Zarate C, - Intranasal Administration of Ketamine to Treat Depression United States Application No. 14/197767 filed on March 5, 2014; United States application or Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) International application No. 14/306382 filed on June 17, 2014; 4): Zarate, C, Charney, DS, Manji, HK, Mathew, Sanjay J, Krystal, JH, Department of Veterans Affairs ”Methods for Treating Suicidal Ideation”, Patent Application No. 14/197.767 filed on March 5, 2014 by Yale University Office of Cooperative Research; 5) Arias A, Petrakis I, Krystal JH. – Composition and methods to treat addiction. Provisional Use Patent Application no. 61/973/961. April 2, 2014. Filed by Yale University Office of Cooperative Research.; 6) Chekroud, A., Gueorguieva, R., Krystal, J.H. “Treatment Selection for Major Depressive Disorder” [filing date June 3, 2016, USPTO docket number Y0087.70116US00]. Provisional patent submission by Yale University; 7) Gihyun, Yoon, Petrakis I., Krystal J.H.—Compounds, Compositions and Methods for Treating or Preventing Depression and Other Diseases. U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 62/444552, filed on January 10, 2017 by Yale University Office of Cooperative Research OCR 7088 US01; and 8) Abdallah, C., Krystal, J.H., Duman, R., Sanacora, G. Combination Therapy for Treating or Preventing Depression or Other Mood Diseases. U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 62/719935 filed on August 20, 2018 by Yale University Office of Cooperative Research OCR 7451 US01. The other authors report no competing interests. Drs. Gelernter and Polimanti are paid for their editorial work on the journal Complex Psychiatry.

References

- Adams RE, Boscarino JA, Hoffman SN, Urosevich TG, Kirchner HL, Boscarino JJ, Figley CR, 2022. Psychological well-being and alcohol misuse among community-based veterans: results from the Veterans’ Health Study. J. Addict. Dis 40 (2), 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Begle AM, Cisler JM, Hernandez MA, Muzzy W, Acierno R, 2011. Prevalence and correlates of poor self-rated health in the United States: the national elder mistreatment study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 18 (7), 615–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhouv T, & Muthen B (2014). Auxilliary variables in mixture modeling: 3-step approaches using Mplus. Retrieved from ⟨https://www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/webnote15.pdf⟩. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB, 2007. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma Stress 20, 1019–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalopoulou C, Stubbs B, Kralk C, Koukounari A, Prince M, Prina AM, 2018. Associations of smoking and alcohol consumption with healthy ageing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMJ Open 8, e019540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold D, Zerach G, 2021. Emotion regulation and experiential avoidance moderate the association between posttraumatic symptoms and alcohol use disorder among Israeli combat veterans. Addict. Behav 115, 106776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuehrlein BS, Mota N, Arias AJ, Trevisan LA, Kachadourian LK, Krystal J, Pietrzak RH, 2016. The burden of alcohol use disorders in US military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Addiction 111 (10). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuehrlein BS, Kachadourian LK, DeVylder EK, Trevisan LA, Potenza MN, Krystal J, Pietrzak RH, 2018. Trajectories of alcohol consumption in U.S. military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Am. J. Addict 27, 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB, 2003. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Pers 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Hasin DS, 2015. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 72 (8), 757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver PR, 1990. Love and work: an attachment-theoretical perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 59, 270–280. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Bucholz KK, Sartor CE, Howell DN, Wood PK, 2005. Drinking trajectories from adolescence to the mid-forties among alcohol dependent males. J. Stud. Alcohol 66 (6), 745–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Blonigen DM, Koenig LB, Wachsmuth W, Price RK, 2010. Course of alcohol dependence among Vietnam combat veterans and nonveteran controls. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 71 (5), 629–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B, 2009. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50, 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell N, Rubin D, 2001. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Lui PP, Chmielewski M, Trujillo M, Morris J, Pigott TD, 2022. Linking big five personality domains and facets to alcohol (mis)use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol. Alcohol. 57 (1), 58–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G, Peel D, 2000. Finite Mixture Models. Wiley, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, 2004. Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D (Ed.), Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Muthen L, 2002. MPlus: The Comprehensive Modeling Program for Applied Researchers. Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthen B, 2007. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling. A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Palmisano AN, Norman SB, Panza KE, Petrakis IL, Pietrzak RH, 2022. PTSD symptom heterogeneity and alcohol-related outcomes in U.S. military veterans: indirect associations with coping strategies. J. Anxiety Disord 85, 102496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW, 1994. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 67, 1063–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg SE, Schnetzer LW, Buchanan EM, 2010. The Purpose in Life Test-Short Form: development and psychometric support. J. Happiness Stud 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Ren L, 2011. Substane use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001-2010: implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 116 (1–3), 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL, 1991. The MOS social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med 32, 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrank WH, Patrick AR, Brookhart MA, 2011. Healthy user and related biases in observational studies of preventive interventions: a primer for physicians. J. Gen. Intern. Med 26 (5), 546–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Ware JE, 1991. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. 10.7249/CV361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonidandel S, LeBreton JM, 2010. Determining the relative importance of predictors in logistic regression: an extension of relative weights analysis. Organ Res. Methods 13, 767–781. [Google Scholar]

- VA Health Care. (2013). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C). Retrieved from ⟨https://www.mirecc.va.gov/cih-visn2/Documents/Provider_Education_Handouts/AUDIT-C_Version_3.pdf⟩. [Google Scholar]

- Vungkhanching M, Sher KJ, Jackson KM, Parra GR, 2004. Relation of attachment style to family history of alcoholism and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 75 (1), 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, & Keane TM (2013). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Instrument available from the National Center for PTSD at ⟨www.ptsd.va.gov⟩. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, & Schnurr PP (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL5) - LEC-5 and extended criterion A [Measurement instrument]. Avaliable from ⟨http://www.ptsd.va.gov/⟩. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson V, Stevelink SAM, Greenberg K, Greenberg N, 2018. Prevalence of mental health disorders in elderly US military veterans: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 26 (5), 534–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2022). Alcohol fact sheet. Retrieved from ⟨https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol⟩.